Effective Aspersions: How the Nonlinear Investigation Went Wrong

The New York Times

Picture a scene: the New York Times is releasing an article on Effective Altruism (EA) with an express goal to dig up every piece of negative information they can find. They contact Émile Torres, David Gerard, and Timnit Gebru, collect evidence about Sam Bankman-Fried, the OpenAI board blowup, and Pasek’s Doom, start calling Astral Codex Ten (ACX) readers to ask them about rumors they’d heard about affinity between Effective Altruists, neoreactionaries, and something called TESCREAL. They spend hundreds of hours over six months on interviews and evidence collection, paying Émile and Timnit for their time and effort. The phrase “HBD” is muttered, but it’s nobody’s birthday.

A few days before publication, they present key claims to the Centre for Effective Altruism (CEA), who furiously tell them that many of the claims are provably false and ask for a brief delay to demonstrate the falsehood of those claims, though their principles compel them to avoid threatening any form of legal action. The Times unconditionally refuses, claiming it must meet a hard deadline. The day before publication, Scott Alexander gets his hands on a copy of the article and informs the Times that it’s full of provable falsehoods. They correct one of his claims, but tell him it’s too late to fix another.

The final article comes out. It states openly that it’s not aiming to be a balanced view, but to provide a deep dive into the worst of EA so people can judge for themselves. It contains lurid and alarming claims about Effective Altruists, paired with a section of responses based on its conversation with EA that it says provides a view of the EA perspective that CEA agreed was a good summary. In the end, it warns people that EA is a destructive movement likely to chew up and spit out young people hoping to do good.

In the comments, the overwhelming majority of readers thank it for providing such thorough journalism. Readers broadly agree that waiting to review CEA’s further claims was clearly unnecessary. David Gerard pops in to provide more harrowing stories. Scott gets a polite but skeptical hearing out as he shares his story of what happened, and one enterprising EA shares hard evidence of one error in the article to a mixed and mostly hostile audience. A few weeks later, the article writer pens a triumphant follow-up about how well the whole process went and offers to do similar work for a high price in the future.

This is not an essay about the New York Times.

The rationalist and EA communities tend to feel a certain way about the New York Times. Adamantly a certain way. Emphatically a certain way, even. I can’t say my sentiment is terribly different—in fact, even when I have positive things to say about the New York Times, Scott has a way of saying them more elegantly, as in The Media Very Rarely Lies.

That essay segues neatly into my next statement, one I never imagined I would make:

You are very very lucky the New York Times does not cover you the way you cover you.

A Word of Introduction

Since this is my first post here, I owe you a brief introduction. I am a friendly critic of EA who would join you were it not for my irreconcilable differences in fundamental values and thinks you are, by and large, one of the most pleasant and well-meaning groups of people in the world. I spend much more time in the ACX sphere or around its more esoteric descendants and know more than anyone ought about its history and occasional drama. Some of you know me from my adversarial collaboration in Scott’s contest some years ago, others from my misadventures in “speedrunning” college, still others from my exhaustively detailed deep dives into obscure subculture drama (sometimes in connection with my job).

The last, I’m afraid, is why I’m here this time around—I wish we were meeting on better terms. I saw a certain malcontent[1] complaining that his abrasiveness was poorly received, stopped by to see what he was on about, and got sucked in—as one is—by every word of the blow-by-blow fighting between two companies I knew nothing about in an ecosystem where I am a neighbor but certainly not a member. I came to this fresh: never having heard of @Ben Pace, @Habryka, or Nonlinear, having about as much knowledge of EA as any outsider can have while having no ties to its in-person community, and with the massive benefit of hindsight in being able to read side-by-side what active EA forum users read three months apart. I pursued it out of sheer fascination when I should have been studying for my Civil Procedure final, entranced by a saga that would not leave my mind.

What precisely do I think of Nonlinear, a group I had never heard of prior to a few days ago? More-or-less what my friends think, really—credit them for the bulk of the following description. It sounds like a minor celebrity got comfortably rich young, dove into the same fascinating online ecosystem we all did, and decided to spend his retirement with his partner (who has an impressive history of dedication to charity) and brother scratching his itch to be productive by traveling the world and doing charity via talking with cool, smart people about meaningful ideas. It sounds like they hired someone who imagined doing charity work but instead lived a life more akin to that of a live-in assistant to a celebrity, picked up another traveling-partner-turned-employee with a long history of tumultuous encounters, and had a lot of very predictable drama of the sort that happens when young people live as roommates and traveling partners with their bosses.

From there, the ex-employees, disillusioned and burnt out, began spreading allegations that toed and sometimes crossed the line between “exaggerated” and “fabricated”, and the founders learned an important lesson about mixing work and pleasure, one that soon turned into the much crueller lesson of what it feels like to be sewn inside a punching bag and dangled in front of your tight-knit community. They made a major unforced tactical error in taking so long to respond and another in not writing in the right sort of measured, precise tone that would have allowed them to defuse many criticisms. They were also unambiguously, inarguably, and severely wronged by the EA/LessWrong (LW) community as a whole.

What about Lightcone, a group I quickly realized maintains LessWrong, the ancestral home of my people? I’m grateful they’ve maintained a community that has inspired me and so many people like me. I get the sense that they’re earnest, principled, precise thinkers who care deeply about ethical behavior. I’ve learned they recently faced the severe blow of watching a trusted community member be revealed as the fraud to end all frauds while feeling like there was something they could have done. I think they met earnest people who talked about feeling hurt and genuinely wanted to help to the best of their ability. And I wish I’d built up sufficient social capital with them to allow it to feel like a relationship of trust rather than the intrusion of a hostile stranger when I say they wrote one of the most careless, irresponsible, destructive callout articles I have ever had the displeasure of reading—one they seem to continue to be in denial about.

In a sense, though, I think they should be thanked for it, because the community reaction to their article indicates it was not just them. I follow drama and blow-ups in a lot of different subcultures. It’s my job. The response I saw from the EA and LessWrong communities to their article was thoroughly ordinary as far as subculture pile-ons go, even commendable in ways. Here’s the trouble: the ways it was ordinary are the ways it aspires to be extraordinary, and as the community walked headlong into every pitfall of rumormongering and dogpiles, it did so while explaining at every step how reasonable, charitable, and prudent it was in doing so.

The Story So Far: A Recap

Starting in mid-2022, two disgruntled former Nonlinear employees, referred to by the pseudonyms Alice and Chloe, began to spread rumors about the misery of their time there. They told these rumors to many people within the EA community, including CEA, requesting that CEA not tell Nonlinear about any of their complaints and pushing for unspecified action against the organization. CEA discussed the possibility of the former employees writing a public post, but they were unwilling to do so. In November 2022, someone made an anonymous post spreading vague rumors about the same. As more rumors spread, some organizations within EA began to restrict Nonlinear’s opportunities in the EA space, such as CEA not inviting them to present at conferences.

Ben Pace, who managed a community hub called the Lightcone offices, heard these rumors when Kat Woods and Drew Spartz of Nonlinear applied to visit the offices in early 2023, and told them he was concerned about them but still allowed a visit. Dissatisfied with Kat’s explanations when he chatted with her, he began to investigate further, spending several hundred hours over six months looking for all negative information he could find about Nonlinear (centering around the experiences of those two former employees) via interviews and investigative research. Others in the Lightcone office participated in this process, with Oliver Habryka reporting the office as a whole spent close to a thousand hours on it. In collaboration with their sources, they set a publication date for an exposé about Nonlinear.

Less than a week before the publication date, Ben informed Nonlinear that he had been digging into them with intent to publish an exposé and sent them a list of concerns. Around 60 hours before publication, Ben had a three-hour phone call with the Nonlinear cofounders about those concerns in which they told him his list contained a number of exaggerations and fabrications. Nonlinear requested a week to compile and present evidence against these claimed fabrications, which Ben and Oliver rejected. The day before publication, longtime community member Spencer Greenberg obtained a draft copy of the post and warned Ben and Oliver that it contained a number of falsehoods. Ben edited some, but when Spencer sent him message records contesting one claim in the post two hours before publication, Lightcone concluded it was too late to change and that the post must release on schedule. During the few days before publication and in particular after seeing a draft copy of the post, the Nonlinear founders grew increasingly urgent and aggressive in their messages, eventually threatening to sue Lightcone for defamation if they released the post without taking another week to investigate Nonlinear’s evidence. Lightcone refused.

Ben released the post on September 7th to the EA/LW communities, where it was widely circulated and supported, including by CEA’s Community Health team.[2] After publishing the post, he paid Alice and Chloe $5,000 each. Kat shared screenshots contesting one of the post’s claims in the comments section and Nonlinear promised a comprehensive reply as soon as possible. On September 15th, Ben released a postmortem sharing further thoughts on Nonlinear and concluding that the CEA Community Health team was not doing enough to police the EA ecosystem. Nonlinear stayed mostly quiet until December 12th, when they released an in-depth post contesting the bulk of the claims in the exposé.

On December 13th, I heard about this sequence of events and the players involved for the first time.

Avoidable, Unambiguous Falsehoods in “Sharing Information About Nonlinear”

If you have a strong stake in Nonlinear’s reputation, I encourage you to read their full response, including the appendix. Here, I will aim towards something simpler: documenting some of the standout times Ben made claims easily and unambiguously contested by primary sources from Nonlinear, mostly about situations that occurred when Alice and Chloe were traveling with them, claims that could and should have been fixed with a modicum of effort. Each subsection that follows will begin with a direct pull quote from Ben’s article and follow with my summary of the evidence Nonlinear provides rebutting it, with sources and specific screenshots in footnotes.

“My current understanding is that they’ve had around ~4 remote interns, 1 remote employee, and 2 in-person employees (Alice and Chloe). Alice was the only person to go through their incubator program.”

Nonlinear has had 21 employees, including five other incubatees. This is a low-importance claim, but it’s illustrative. Clarifying with Nonlinear, who was not only willing to clarify points with them but begging to do so, would have taken no time at all. To avoid fact-checking this demonstrates a low priority for fact-checking in general.[3]

“they were not able to live apart from the family unit while they worked with them”

Per Nonlinear, Alice lived apart from them for six weeks during her four months of employment. This is a slight exception to my “primary source” rule—verifying whether Alice lived apart for six weeks would take a bit more work than just Nonlinear’s word, but it directly contradicts Ben’s claim such that publication of the original claim becomes irresponsible.[4]

“Chloe’s salary was verbally agreed to come out to around $75k/year. However, she was only paid $1k/month, and otherwise had many basic things compensated i.e. rent, groceries, travel. This was supposed to make traveling together easier, and supposed to come out to the same salary level.”

Nonlinear clearly explained Chloe’s compensation scheme from the beginning and presented it in a clear and unambiguous written contract, which they fulfilled.[5] It was always conceptualized and presented as $1000 a month plus living expenses. She accepted the position knowing its compensation. It’s not a level of compensation I’d advise anyone in it for the money to take, but the experience is the sort that many young people, including me, have pursued knowing there’s a monetary tradeoff.

I don’t agree with Nonlinear’s apparent conception of benefits as functionally equivalent to pay given my experience in comparable situations (the military and a Mormon mission)[6], but Chloe had no serious grounds to complain about salary, and Ben’s description of it ignores the actual employment agreement and misrepresents the situation.

“Over her time there she spent through all of her financial runway, and spent a significant portion of her last few months there financially in the red (having more bills and medical expenses than the money in her bank account) in part due to waiting on salary payments from Nonlinear. She eventually quit due to a combination of running exceedingly low on personal funds and wanting financial independence from Nonlinear, and as she quit she gave Nonlinear (on their request) full ownership of the organization that she had otherwise finished incubating.” … “At the time of her quitting she had €700 in her account, which was not enough to cover her bills at the end of the month, and left her quite scared. Though to be clear she was paid back ~€2900 of her outstanding salary by Nonlinear within a week, in part due to her strongly requesting it.”

Timed transactions straightforwardly demonstrate that aspects of Alice’s claims about waiting for salary payments were false. Kat also explains that the delay in expense reimbursement was because Alice switched from recording in their public reimbursement system to using a private spreadsheet without telling them, and that they reimbursed Alice as soon as she told them. While the document provides no primary source on this, as with the “not allowed to live apart” claim, the counterclaim provides ample reason to either verify more closely or avoid publishing the falsehood.[7]

“One of the central reasons Alice says that she stayed on this long was because she was expecting financial independence with the launch of her incubated project that had $100k allocated to it (fundraised from FTX). In her final month there Kat informed her that while she would work quite independently, they would keep the money in the Nonlinear bank account and she would ask for it, meaning she wouldn’t have the financial independence from them that she had been expecting, and learning this was what caused Alice to quit.”

Nonlinear provides two screenshots to support an in-depth narrative that Alice’s role was always as a project manager within Nonlinear, that they clarified repeatedly that she was a project manager within Nonlinear, that all of the funding in her project came via Nonlinear, that they would never have simply handed a quarter-million dollars to an untested new organization, and that Alice repeatedly attempted to claim she had a separate organization despite that.[8]

Ben’s quoted claim is not technically false: Alice did indeed seem to believe, or claim to believe, that she would get financial independence. It provides a misleading impression, though, to present it without any of the context and primary sources available from Nonlinear.

“Alice quit being vegan while working there. She was sick with covid in a foreign country, with only the three Nonlinear cofounders around, but nobody in the house was willing to go out and get her vegan food, so she barely ate for 2 days. Alice eventually gave in and ate non-vegan food in the house. She also said that the Nonlinear cofounders marked her quitting veganism as a ‘win’, as they had been arguing that she should not be vegan.”

There was vegan food in the house and they picked food up for her while sick themselves, but on one of the days they wanted to go to a Mexican place with limited vegan options instead of getting a vegan burger from Burger King.[9] “Nobody in the house was willing to go out and get her vegan food” is unambiguously false. Crucially, Ben had sufficient information to know it was false before the time of publication.

“Alice was polyamorous, and she and Drew entered into a casual romantic relationship. Kat previously had a polyamorous marriage that ended in divorce, and is now monogamously partnered with Emerson. Kat reportedly told Alice that she didn’t mind polyamory “on the other side of the world”, but couldn’t stand it right next to her, and probably either Alice would need to become monogamous or Alice should leave the organization.”

Kat points out that she recommended poly people for Alice to date multiple times, but felt strongly that Alice dating Drew (her colleague, roommate, and the brother of her boss) would be a bad idea. I happen to agree with her reasoning on that front and think subsequent events vindicated her. I find this claim particularly noxious because advising someone in the strongest possible terms against dating their boss’s brother, who lives with them, seems from my own angle like a thoroughly sane thing to do. Kat’s advice on that front was wholly vindicated.[10]

“Before she went on vacation, Kat requested that Alice bring a variety of illegal drugs across the border for her (some recreational, some for productivity). Alice argued that this would be dangerous for her personally, but Emerson and Kat reportedly argued that it is not dangerous at all and was “absolutely risk-free”. Privately, Drew said that Kat would “love her forever” if she did this.”

When you read “bring a variety of illegal drugs across the border [...] (some recreational, some for productivity),” do you think “stop by a pharmacy for ADHD meds”? I do not. It conjures up images of cartels, of back-alley meth deals, of steep danger and serious wrongdoing. For many responding to the original post, this was one of the most severe indicators of wrongdoing. If it had been accurately reported, whatever people think about casual Adderall use, it simply would not have had the same impact.[11] Oliver asserts his belief that more is being covered up here—I have no basis on which to judge this, but if so, it would have been an excellent point for Ben to confirm and present in specific while writing an article on the matter.

Ben and Oliver focus a great deal on the amount of time and effort that went into the post: 100-200 hours per the original post, 320 hours per Ben’s postmortem, somewhat over 1000 hours spread over the Lightcone staff per a comment from Oliver. They and the community alike use this time and effort to justify the difficulty of an investigation like this, the impracticality of asking for more, the high standards that went into the investigation, and the lack of need to add any sort of delay.

I believe they spent that time in productive, reasonable ways, but I keep coming back to an inescapable conclusion about it all: You can do a lot of cross-checking of a lot of claims in a thousand hours, but without talking with the people involved, you can do very little to cross-check the core allegations. The bulk of the claims I list above, and the bulk of the claims the community seems to have found most alarming, occurred in times and places where there were precisely five people present. Ben and Oliver spent a thousand hours diligently avoiding three of those five people while hearing and collecting rumors that they were vile, spent three hours with a publication date already set dumping every allegation on them at once, then flat-out refused to wait so much as a week to allow those three people to compile concrete material evidence against their claims.

They were, in fact, in such a hurry to release that when Spencer Greenberg got a last-minute look at the draft and warned them of serious inconsistencies, they hurriedly adjusted some before pleading lack of time on another and treating an update in the comments section as sufficient. Oliver claims, and I have little reason to contest, that Ben published (almost) nothing he knew was wrong at the time. But they both knew they were receiving information contradicting their claims up until the moment of publication and being promised more of that information shortly.

The errors in this section and in the process that led to it are inexcusable for any published work purporting to be the result of serious investigation. They cannot be said to be either trivial or tangential. These are not the results of a truth-seeking process.

These Issues Were Known and Knowable By Lightcone and the Community. The EA/LW Community Dismissed Them

The original post and the discussion around it contained three glaring red flags:

At the top, Ben reminded the community that the bulk of the post came from a search for negative information, not for a complete picture.

In the comments, @spencerg, someone with a long history of good faith and fair dealing in the rationalist community, warned that the post contained many false claims, some of which he had warned Ben of immediately before publishing and Ben took half-hearted measures to correct.

Also in the comments, @Geoffrey Miller, with his own long history of serious, sincere engagement within the rationalist community, exhorted the community to adhere to the standards of professional investigative journalism—learned from bitter experience—and to be professionally accountable for truth and balance—and warned that the post realistically failed that standard.

The community treated Ben’s admission that he had been on a six-month hunt for negative information not as a signal saying “I am writing a slanted hit piece” the way they would if it came from any news organization in the country, but as one of good epistemic hygiene and honesty that would allow them to rationally and accurately update.

Judging by votes, people were somewhat receptive to Spencer and politely heard him out, but they did little to update based on his claims. Oliver’s response, claiming that the lawsuit threat was an attempt at intimidation that justified immediate release of all information and that 40 more hours of lost productive time was unreasonable to ask, was overwhelmingly more popular—indeed, about as popular as a response gets in this ecosystem.

Geoffrey’s reception was decidedly more mixed. The bulk of the community emphatically rejected Geoffrey’s push to heed professional standards, with people claiming that in many cases those standards simply existed to protect the professionals, citing a general distrust for established codes of professions and for the standards of investigative journalism in specific, and claiming those standards set the bar too high for an already thankless task.

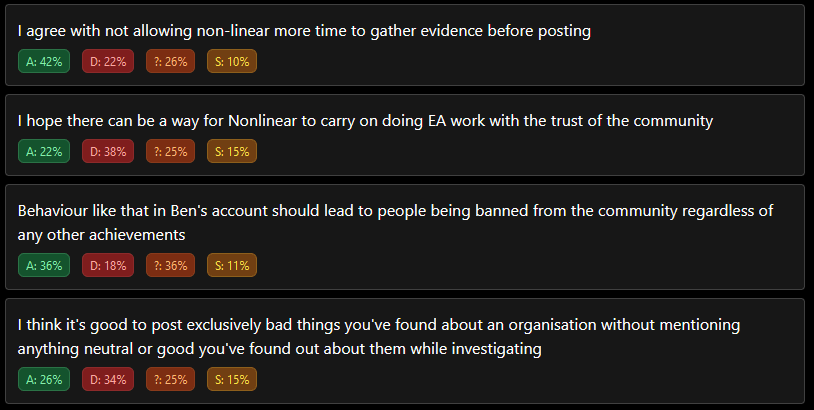

In addition, a plurality of the community who voted in @Nathan Young’s poll agreed with the decision not to delay posting.

It is well and good to distrust journalism. I do myself. I confess, though, that in all my time hearing how my spheres criticize journalists, I have never once heard people complain that they work too hard to verify their information, try too hard to be fair to the subjects of their writing, or place too high a premium on truth.

As Geoffrey points out, the crux is “how bad it is to make public, false, potentially damaging claims about people, and the standard of care/evidence required before making those claims.”

I can’t say this is a crux I expected among rationalists, but here we are.

Oliver claims that Ben’s goal with the post was not to judge, but to publish evidence that had been circulating and allow for refutation. That is hard to square with lines like “I expect that if Nonlinear does more hiring in the EA ecosystem it is more-likely-than-not to chew up and spit out other bright-eyed young EAs who want to do good in the world,” hard to square with Ben’s repeated assertions that claims in his post were credible, and hard to square with the duty you take on by electing to publish an exposé about someone and telling people they can trust it due to the time you put into it and your stature within the community. You have to play the role of judge in a scenario like that.

It’s worth examining the code of ethics for the Society of Professional Journalists. A respect for truth as their fundamental aim is written into their first, second, and third principles:

Ethical journalism should be accurate and fair. Journalists should be honest and courageous in gathering, reporting and interpreting information.

Journalists should:

Take responsibility for the accuracy of their work. Verify information before releasing it. Use original sources whenever possible.

Remember that neither speed nor format excuses inaccuracy.

Provide context. Take special care not to misrepresent or oversimplify in promoting, previewing or summarizing a story.

I believe this is a fair, reasonable, and minimal standard for anyone aiming to do investigative work. It is not sufficient to claim epistemic uncertainty when promoting falsehoods, nor is it sufficient to say you are simply amplifying the falsehoods of your sources.

When you amplify someone’s claims, you take responsibility for those claims. When you amplify false claims where contradictory evidence is available to you and you decline to investigate that contradictory evidence, you take responsibility for that. People live and die on their reputations, and spreading falsehoods that damage someone’s reputation is and should be seen as more than just a minor faux pas.

Ben, so far as I can tell, disputes this standard, holding instead that past a relatively low threshold, unverified allegations should be spread: “I think I’m more likely to say “Hey, I currently assign 25% to <very terrible accusation>” if I have that probability, assigned rather than wait until it’s like 90% or something before saying my probability.” His response to Nonlinear’s rebuttal makes the reasonable-sounding statement that he plans to compare factual claims to those in his piece and update inaccuracies, but a high tolerance for spreading falsehoods is built into his process. Correction is the bare minimum of damage control after spreading damaging falsehoods, not prudence following a pattern of prudence.

Better processes are both possible and necessary

Oliver explicitly disputes the journalistic standard. He asserts that the “approximate result of [the standard I ask] is that [they] would have never been able to publish.” When I pushed back, he encouraged me “to talk to any investigative reporter with experience in the field and ask them whether [my] demands here are at all realistic for anyone working in the space.”

I agree that they would never have been able to publish a list of unsubstantiated rumors, and consider that a good thing: to quote a friend, a healthy community does not spread rumors about every time someone felt mistreated. But I emphatically disagree that they would never have been able to publish anything at all. I would never think to hold them to a standard I do not hold myself to.

As reassurance, Oliver cites how their investigative efforts are a “vast and far outlier,” both in the realm of willingness to pay sources[12] and “on the dimension of gathering contradicting evidence.”[13]

He is technically correct: they are indeed an outlier. Just not, unfortunately, in the way he intends.

I am not a journalist. The only time in my life I have been paid to write, or indeed have sought payment for that writing, was in Scott’s 2018 Adversarial Collaboration Contest. When I write, I do so in my spare time in quiet corners of the internet, often out of the motivation that only comes when Someone Is Wrong On The Internet and when by all rights I should be doing something else. Some of the topics I focus on read as bizarrely trivial on their face rather than the world-saving EAs prefer to focus on, as with my detailed account of the fall of r/antiwork and the backstory behind a viral moment of a pirate furry hitting someone with a megaphone. We all have our fascinations.

Consider that latter article. The “antagonists” were not particularly communicative, but I reached out to them multiple times, including right before publication, checking if I could ask questions and asking them to review my claims about them for accuracy. I went to the person closest to them who was informed on the situation and got as much information as I could from them. I spent hours talking with my primary sources, the victim and his boyfriend, and collecting as much hard evidence as possible. I spent a long time weighing which points were material and which would just serve to stir up and uncover old drama. Parties claimed I was making major material errors at several points during the process, and I dug into their claims as thoroughly as I could and asked for all available evidence to verify. Often, the disputes they claimed were material hinged on dissatisfaction with framing.

All sources were, mutually, worried about retribution and vitriol from the other parties involved.[14] All sources were part of the same niche subculture spaces, all had interacted many times over the past half-decade, mostly unhappily, and all had complicated, ugly backstories.

From my conclusion to that story:

The obscurity became its own justification. Little tragedies happen all the time and are forgotten by the broader world as quickly as they arise. [...] In the end, I pursued this story for a simple reason: nobody else would. If people are to become outcasts among outcasts, to have their names and faces forever tied to allegations of behavior and beliefs so heinous they justify ostracization and physical assault, the least they deserve is someone willing to tell their story.

I did this in my spare time, of my own initiative, while balancing a full law school schedule. I approached it with care, with seriousness, and with full understanding of the reputational effects I expected it to have and the evidence I had backing and justifying those effects. Writing about someone means taking on a duty to them, particularly if you write to condemn them.

There is no threshold for hours of engagement. The test is accuracy. If you are receiving or seem likely to receive new material facts that contradict elements of your narrative, you are not ready to publish.

I want to pause for a moment on this: I spend hours upon hours verifying obscure trivia in niche stories with minuscule real-world impact. This obsession is hardly a virtue, but the standards of truth-seeking I demand are not too onerous—not for a story about internet nonsense, and certainly not for a controversy that could change the course of lives.

My own credibility is limited by my amateur status and relative inexperience. I’m not an investigative reporter, much as I LARP as one online.[15] Since my job puts me in close proximity to them, though, Oliver and I worked together to write a hypothetical to pose to experienced journalists, in line with his challenge to me, with our opposite expectations preregistered. I don’t endorse the hypothetical as a fully accurate summary of what happened, but agreed that it was close enough to get worthwhile answers.

The hypothetical we came up with:

Say you were advising someone on a story they’d been working on for six months aimed at presenting an exposé of a group their sources were confident was doing harm. They’d contacted dozens of people, cross-checked stories, and did extensive independent research over the course of hundreds of hours.

Their sources, who will be anonymous but realistically identifiable in the article, express serious concerns about retribution and request a known-in-advance publication date.

They have talked to the group they are investigating multiple times to gather evidence, but have not informed them that they are planning to release an exposé with the evidence they gathered. 7 days before their scheduled publication date they contact the group and inform them about their intent to publish and the key claims they are planning to include in their exposé.

The group claims that several points in their article are materially wrong and libelous and asks for another week to compile evidence to rebut those claims, growing increasingly frantic as the publication date approaches and escalating to a threat of a libel suit.

On the last day before publication, they show a draft to another person close to the story who points out a detail that does not directly contradict anything in the post, but seems indirectly implied to be false, which they correct in the final publication. Then with two hours to go before the scheduled publication, the same contact provides evidence against one of the statements made in the post, though also does not definitely disprove it.

Would you advise them to publish the article in its current form, or delay publication, despite the credible requests about the sources about retribution and the promise of the scheduled publication date?

I posed that hypothetical as written, with a brief, neutral leadup, to several journalists.[16] Ultimately, I received three answers, two from my bosses and one from Helen Lewis of The Atlantic. I understand if people would prefer to discount the answers from my bosses due to my working relationship with them, but I believe the framing and lack of context positioned all three well to consider the question in the abstract and on the merits independent of any connections. None were aware of the actual story in advance of answering, only the hypothetical as presented, and none of their answers should be taken as positions on the actual sequence of events.

First, from Katie Herzog, who formerly wrote for The Stranger and currently cohosts the podcast Blocked and Reported:

I would delay publication. I’m not sure about the specifics of libel law but putting myself in a publisher’s shoes, they do tend to not want to get sued and your first commitment, beyond getting the scoop or even stopping the hypothetical group from doing harm, should be towards accuracy.

Oliver requested I clarify that the concern is solely ethical responsibility, not lawsuits. When I asked whether it mattered, she responded:

[I]t doesn’t, really. [A]ccuracy is paramount under threat of legal action or not.

Second, from Jesse Singal, formerly of NYMag with bylines in many outlets, author of The Quick Fix: Why Fad Psychology Can’t Cure Our Social Ills and cohost of Blocked and Reported:

I think it depends a lot on the group’s ability to provide evidence the investigators’ claims are wrong. In a situation like that I would really press them on the specifics. They should be able to provide evidence fairly quickly. You don’t want a libel suit but you also don’t want to let them indefinitely delay the publication of an article that will be damaging to them. It is a tricky situation! I am not sure an investigative reporter would be able to help much more simply because what you’re providing is a pretty vague account, though I totally understand the reasons why that’s necessary.

Finally, from The Atlantic’s Helen Lewis, former deputy editor of the New Statesman and author of the book “Difficult Women: A history of feminism in 11 fights”:

This feels like a good example of why you shouldn’t over-promise to your sources—you want a cordial relationship with them but you need boundaries too. I can definitely see a situation where you would agree to give a source a heads up once you’d decided to publish — if it was a story where they’d recounted a violent incident or sexual assault, or if they needed notice to stay somewhere else or watch out for hacking attempts. But I would be very wary of agreeing in advance when I would publish an investigation—it isn’t done until it’s done.

In the end the story is going out under your name, and you will face the legal and ethical consequences, so you can’t publish until you’re satisfied. If the sources are desperate to make the information public, they can make a statement on social media. Working with a journalist involves a trade-off: in exchange for total control, you get greater credibility, plausible deniability and institutional legal protection. If I wasn’t happy with a story against a ticking clock, I wouldn’t be pressured into publication. That’s a huge risk of libelling the subjects of the piece and trashing your professional reputation.

On the request for more time for right to reply, that’s a judgement call—is this a fair period for the allegations involved, or time wasting? It’s not unknown for journalists to put in a right to reply on serious allegations, and the subject ask for more time, and then try to get ahead of the story by breaking it themselves (by denying it).

You don’t even have to look as far as my examples, though. To his credit, Oliver repeatedly asked for better examples of what to do in similar situations. To the credit of the rationalist community, it contains some of those examples. To Oliver’s discredit, however, he had full awareness of one better example, as his response to allegations of community misconduct was one of its subjects of investigation.

Last year, a rationalist meetup organizer faced accusations of misconduct, Oliver and his wife Claire (who was in charge of meetup organization as a whole) banned him from an event, he objected, and Claire agreed to be bound by a community investigation. One principle used in that investigation is worth highlighting:

Anyone accused of misconduct should promptly be informed of any accusations made against them and given an opportunity to tell their side of the story, present evidence, and propose witnesses. Emergency preliminary actions should be taken where allegations are sufficiently serious and credible, but the accused should be given an opportunity to defend themselves as quickly as possible.[17]

In the end, the team writing the report highlighted several specific allegations against its primary subject before including a telling line:

We were unable to substantiate any other allegations made against [redacted]. At his request, we are not repeating unsubstantiated allegations in this document.

A prudent decision.

On Lawsuits

One of the strongest and most universal sentiments shared in response to Ben’s post was that threatening a lawsuit was completely unacceptable. A notable example:

More confidently than anything on this list, Nonlinear’s threatening to sue Lightcone for Ben’s post is completely unacceptable, decreases my sympathy for them by about 98%, and strongly updates me in the direction that refusing to give in to their requested delay was the right decision. In my view, it is quite a strong update that the negative portrayal of Emerson Spartz in the OP is broadly correct. I don’t think we as a community should tolerate this, and I applaud Lightcone for refusing to give in to such heavy-handed coercion.

I get the skepticism, but no matter how much you dislike defamation lawsuits, you should like actual defamation less.

Earlier, I linked to a comment emphasizing distrust in established code of professions in favor of another standard: “this group thought about this a lot and underwent a lot of trial by fire and came up with these specific guidelines, and I can articulate the costs and benefits of individual rules.”

I am not a romantic about the law. It is an unwieldy, bloated beast that puts people through the wringer even when they win. The powerful can wield it against the weak. It is selectively enforced, in what feel at times like all the worst moments.

In common law countries, though, it is something else as well: the result of collective society thinking a lot, undergoing a lot of trial by fire, and coming up with specific guidelines to bring people as close as possible to being made whole again after they suffer injustices we have collectively deemed to be intolerable. The best judges understand precisely what the law is:

A case is just a dispute. The first thing you do is ask yourself—forget about the law—what is a sensible resolution of this dispute? The next thing … is to see if a recent Supreme Court precedent or some other legal obstacle stood in the way of ruling in favor of that sensible resolution. And the answer is that’s actually rarely the case.

The common law is, for the most part, pleasantly intuitive. I like to say it’s all vibes. A great deal of common law hinges on the “reasonable person” standard, either explicitly or implicitly: is it sensible to do this? Good. Then do it. Is it unreasonable? Then don’t.

The court of law is, in short and aspirationally, a last-ditch way to force people to right wrongs without escalating to force. Few disputes reach the point of lawsuits. Fewer still make it past discovery and into trials without settlements. Yet fewer see dueling parties fight bitterly up the chain of appeals. Throughout the cases I read as a first-semester law student, a message drilled in by judge after judge throughout history is that nobody wants to see the inside of a court. If you can handle wrongs in your life on your own, not even the judges want you there.

Threats of lawsuits are fundamentally different to other threats. They are, as @Nathan Young put it, bets that the other party is so wrong you’re willing to expend both of your time and money to demonstrate it. Rationalists are fond of Yudkowsky’s line: “Bad argument gets counterargument. Does not get bullet. Never. Never ever never for ever.” If it can be had nowhere else, the court is the way to get that counterargument, and I concur with @Daystar Eld that people should not be “shunned, demonized, etc for threatening to use a very core right that they’re entitled to.”

Making firm statements about the law when I am not a lawyer is perilous, and the legal paper I had to write outlining the ways lawyers can get sued for malpractice for casual false advice to friends is fresh in my mind. Still, my impression is that many here misunderstand libel law somewhat, and the actual standard is worth clarifying. I’ll start with a comment from Oliver:

The original post is really quite careful in its epistemic status and in clearly referencing to sources claiming something. You could run this by a lawyer with experience in libel law, and I think they would conclude that a suit did not have much of a chance of success.

I will make no specific legal claims about the original post. Inasmuch as I am interested in the legal standard, it is primarily as a baseline for the ethical standard. It’s worth examining, however, the standards of defamation law.

Referencing claims made by specific sources:

Under Restatement (Second) of Torts § 578, a broadly but not universally accepted summation of common law torts, someone who repeats defamatory material from someone else is liable to the same extent as if they were the original publisher, even if they mention the name of the original source and state they do not believe the claim. Claims of belief or disbelief, while not determinative, come into play when determining damages.

Two Supreme Court cases, St. Amant v. Thompson, 390 U.S. 727 (1968) and Harte-Hanks Communications, Inc. v. Connaughton, 491 U.S. 657 (1989), showcase how people can be liable solely for repeating someone else’s defamatory claims. In St. Amant, a politician who read his own questions and someone else’s false answers in an interview was found not liable only because actual malice could not be proven. In Harte-Hanks, a newspaper was found liable for libel solely for quoting a witness who falsely claimed she was offered a bribe in exchange for favorable testimony.

Epistemic uncertainty:

Restatement (Second) of Torts § 566 touches on expressions of opinion, clarifying that opinions are actionable to the extent they are based on express or implied defamatory factual claims.

Per Milkovich v. Lorain Journal Co., 497 U.S. 1 (1990), opinions that rest on factual claims (e.g. “In my opinion John Jones is a liar”) can imply assertions of objective fact, and connotations that are susceptible to being proven true or false can still be considered. Opinions are not privileged in a way fundamentally distinct from facts.

In short, you do not dodge liability for defamation by attributing beliefs to your sources or by clarifying you don’t know whether an accusation is true.

Lawsuit threats are distinctly unfriendly. Here’s another thing that’s distinctly unfriendly: publishing libelous information likely to do irreparable damage to an organization without giving them the opportunity to proactively correct falsehoods. The legal system is a way of systematizing responses to that sort of unfriendliness. It is not kind, it is not pleasant, but it is a legitimate response to a calculated decision to inflict enormous reputational harm.

At the time Nonlinear threatened legal action, they honestly believed that they were about to be libeled and that they had hard material evidence that would be sufficient to prove that libel in a court of law. They may be correct, they may be incorrect, but at the time they made that threat they were already on trial, with Ben Pace as prosecutor and judge alike, and no defense attorney to be found.

A threat of legal action in a circumstance like that should serve not as a defection from a frame of cooperation, but as a reminder that you are already in a fundamentally adversarial frame, having chosen to investigate a group over a long period of time and then publish information to damage them. It should serve as a warning: not “get this information out immediately at all cost,” but “If you cannot deescalate, someone will win here and someone will lose. Dot every i. Cross every t. Make your own behavior unimpeachable, because every action you take will be under strict scrutiny.”

The adversarial frame began when Alice and Chloe began sharing rumors about Nonlinear that people used to justify changing their behavior around the company members without verifying with them. It continued when Lightcone elected to spend six months digging up all possible negative information about them, when they reached out with a publication date already set, and when they refused to delay publication a moment to allow counter-evidence. At no stage can this be said to have been a collaborative process.

If your goal is to reveal the truth and not to inflict harm on someone, you should wait until you have all sides as thoroughly as you can reasonably get them, not cut that process short when the party you are making allegations against responds with understandable antagonism—until and unless they refuse to cooperate further and have no more useful information to give.

First Principles, Duty, and Harm

The EA/LW community loves to think from first principles, and that is usually one of its finest traits. I notice and respect the times their first-principles thinking leads them to be correct about things broader society is incorrect about—a regular occurrence. Occasionally, though, this manifests in a way satirized by SMBC and many others: confidence that they can outperform others from first principles leading them to make painfully predictable missteps in other fields.

It would be hypocritical of me to criticize the desire to do amateur investigative journalism, to be the one to show up and do things where others do not. Ben Pace, in defending his decision to write his article, used a quote from Eliezer Yudkowsky I am also fond of:

But if there’s one thing I’ve learned in life, it’s that the important things are accomplished not by those best suited to do them, or by those who ought to be responsible for doing them, but by whoever actually shows up.

When you say “I want to make the world a better place,” though, you add an implicit “I want power and should be trusted with it.” People should do good, say things worth saying, and get involved in causes that matter to them, but every time they do so, they enmesh themselves in a web of responsibilities. The assertion of power is neither trivial nor costless. I do more amateur investigative work than almost anyone else I know of, without formal training, often without pay, and without any stamp of approval from a profession, and Lightcone has and should have the same privilege. But responsibility must accompany it.

Ben felt a clear sense of responsibility to Alice and Chloe. He felt a responsibility, too, to the community of Effective Altruism. Both are admirable. Somewhere along the way, though, spurred by those responsibilities and the feeling that he had a duty to speak out, he stopped feeling that same sense of responsibility to Nonlinear.

One of the most unsavory critics of the rationalist community coined the meme of rationalists as quokkas: profoundly innocent and naïve souls who can’t imagine you might deceive them. This describes a failure state of rationalism, I think, but certainly not the central case. He is rightly unpopular around here and I hesitate to give further life to his metaphor by extending it, but in seeing rationalists reinvent the pettiest and most destructive subculture drama I find everywhere else from first principles, all while working to be even-handed and earnest, I have thought of nothing so much as a quokka with a machine gun.

Ben’s post, in all honesty, seems naïve: that if you just state you only looked for the negative, people will add it to a carefully balanced judgment rather than treat it as a complete picture; that if you share negative information about someone and the truth comes out later people will simply update and the original damage is undone; that uncertainty about whether someone has done an awful thing should be handled the same way as other public uncertainty—that you can, in short, write a hit piece full of unverified gossip and rumors, but Rational.

That is not flattering, it is not kind, but it is what I see in this saga: First-principles thinking without sufficient consideration towards harm, brushing aside the safeguards people have felt out over centuries of building the common law and codes of ethics. Pure harm, in a sense. Innocent, well-meaning, earnest harm. But harm nonetheless.

What of Nonlinear?

Effective Altruists wish to avoid adjudicating truth claims in court and believe they can and should do better in-house. Very well, but you would do well to adopt some choices from the courts in that process.

Lightcone elected to try Nonlinear in the court of public opinion, putting the question of their reputation to a jury of their peers. They did so by means of a post that was openly biased and contained a wide range of falsehoods for which they concede slight, if any, fault. They offered no semblance of due process, providing a single three-hour phone call to respond to six months of work and declining to examine any further exculpatory evidence. Their post, embraced and accepted by their community, caused immense and irrevocable material harm to Nonlinear. The community had a chance to notice and proactively correct those flaws. It did not and indeed dismissed those who raised them. CEA noticed and endorsed the trial, having likewise deliberately neglected Nonlinear’s side of the story.

From all of this, I find myself drawn to only one outcome: Declare a mistrial, likely at least by retracting the initial article with a public apology, the same as responsible journalists do after publishing sufficiently false articles. Was Nonlinear at fault in some of its interactions? Probably! Were they their own worst enemies in the way they responded? Certainly. Does it matter anymore? Not at all. The community mishandled this so badly and so comprehensively that inasmuch as Nonlinear made mistakes in their treatment of Chloe or Alice, for the purposes of the EA/LW community, the procedural defects have destroyed the case.

I know neither Ben nor Oliver but respect their roles in this community and think that they were acting with serious efforts to apply rationalist/EA principles, neither of which I claim the mantle of. I spent the bulk of this essay criticizing their approach in ways that necessarily come off as hostile and painful towards an investigation they poured their hearts into over the course of half a year, but I think the lack of community self-correction to that approach and the failure to heed the red flags raised by Spencer Greenberg, Geoffrey Miller, and others are an order of magnitude more serious than anything either of them did. Inasmuch as people should correct from this, I believe the community as a whole is at fault.

This is my first top-level post on the Effective Altruism forums and, surprisingly, my first on LessWrong as well. I am used to writing to adjacent communities and in my own sphere, not here. I have written at such length here, rather than elsewhere, because I fundamentally and deeply respect many of the discourse norms here. This saga damaged that respect—pretty badly, in some ways—and reveals what I believe to be deep-running structural flaws in this ecosystem, implicating many people I have long followed and respected, but if there is one thing I know and respect about the EA/LW community, it is that you engage seriously and carefully with criticism.

As a community, you go to great lengths to do good—more, certainly, than I can claim. You’re human, though. Give each other some grace.

And hey, next time you need a hit piece written?

Leave it to the New York Times.

- ^

- ^

A member of the CEA community health team tells me they “tend to write messages of support for people going through or trying to protect others going through hard things, without necessarily supporting all their methods.” I think they in particular have been in a complex spot trying to navigate many competing demands and I sympathize with the difficulty.

- ^

- ^

- ^

- ^

Benefits and pay just aren’t 1:1 comparable. I’ve had a lot of experience living in similar situations. During my early time in the Air Force, living and training expenses were covered in full and I was paid some $2200 a month (pay is public if you’d like more details). This was a great situation for me and I was able to save some 90% of my salary while living comfortably and happily. Later on, though, I got to choose my housing and food and got housing and food stipends added to my salary. I chose cheaper housing and cheaper food and saved much more money as a result.

Someone wanting to describe my military compensation could do so in several ways:

1. Raw salary while I got no housing/food allowance, then salary + allowances afterwards. This would be the answer in terms of pure income.

2. Salary + equivalent value of allowances, both at the start and later. This would have relatively overstated my compensation early on compared to the first option, since I got more money in my pocket without a decline in subjective quality of life when I got money instead of housing and food.

3. Salary + allowances + benefits (eg free health+dental, later GI Bill, travel). This is an honest account of true compensation, probably the “truest” number I could choose, but it overstates the cash value of every benefit.

4. My cost to the military. This would be astronomically higher than my compensation given the cost of my training and upkeep. Thinking too much about this number unsettles me.

Nonlinear, it seems, is choosing somewhere between 3 and 4 to describe compensation. Having employees is expensive, more so when you want them to travel with you. Not all costs to you are reflected in their take-home pay. Military enlistment is not traditionally considered a high-paying career, but an E-1 fresh out of high school makes more take-home pay than Chloe did. That said, claims about military pay aside, I felt my own compensation was extraordinarily generous at every stage of my time in the Air Force.My Mormon mission provides another basis of comparison. At the time I served, every two-year missionary paid $10,000 for the experience. From there, every cost was fully covered by the mission, with a small (few hundred dollar) stipend for food and incidentals that we still conceptualized as “the Lord’s money.” Costs to the LDS church vary wildly by mission location, but it would be odd to describe those costs as compensation at all. I did not and do not consider this structure abusive. Though I left Mormonism afterwards, my mission was the key formative experience of my life, with some of the worst and best experiences I’ve had and exposure to a slice of the world I had no other way to experience.

I think Nonlinear should have avoided putting a value estimate on benefits since that anchors expectations in an unproductive way, instead simply describing the benefits and letting people work it out for themselves.

- ^

- ^

- ^

I include this for completeness, but those familiar with the story are probably most familiar with this claim, since Kat posted screenshots demonstrating this in reply to the original article.

- ^

- ^

- ^

Paying sources, or checkbook journalism, is typically reserved for tabloids and paparazzi in the United States. Most mainstream papers ban it out of concern about introducing conflicts of interest, reducing the journalist’s ability to remain objective, and undermining credibility of information. More outlets in Europe follow a cultural norm of being willing to pay, but it is not stinginess that causes most American outlets to shy away from paying sources.

- ^

I confess I find his position paradoxical: on the one hand, they put more effort and care in than others; on the other, the standard used by professional journalists is too onerous.

- ^

Fears of retribution are the baseline norm for anybody sharing negative information about anybody else with an eye towards broad publication. There are few more common fears to hear from sources.

- ^

It would, however, probably take substantially less than $800k a year to persuade me to become one.

- ^

The full text of the messages I sent, with hypo text truncated:

- ^

I had a long and somewhat confusing conversation with Oliver over whether the panel members endorsed this paragraph, with him claiming they may have either changed their mind about the paragraph or would not believe it applied to the Nonlinear situation based on private conversations he’d had with them. The panelist who I discussed things with stands by everything in the report.

I missed the review notification while it would have been timely, but it’s worth writing a self-review now that I’ve seen the notification.

I continue to endorse this post in full and believe subsequent events have borne out my decision to write and publish it as I did, when I did. At the time, Lightcone mentioned they were working on another reply to Nonlinear, and it would have been better to wait before writing a comprehensive reaction. Almost a year and a half later, no reply ever came. Looking back at this sequence of events, I remain impressed with the way the effective altruism community responded to my post and unimpressed with the way the rationalist community responded. It continues to color my impression of the rationalist community.

I can’t object to decisions to let topics fade quietly—heaven knows I have plenty of posts I mean to write and never quite get around to—but I do think it’s worth explicitly emphasizing that I learned nothing in public or in private that meaningfully changes my assessment of the situation or my decision to publish this post precisely as I did.

I recall thinking this article got a lot right.

I remain confused about the non-linear stuff, but I have updated to thinking that norms should be that stories are accurate not merely informative with caveats given.

I am glad people come into this community to give critique like this.