Possibility and Could-ness

This post is part of the Solution to “Free Will”.

Followup to: Dissolving the Question, Causality and Moral Responsibility

Planning out upcoming posts, it seems to me that I do, in fact, need to talk about the word could, as in, “But I could have decided not to rescue that toddler from the burning orphanage.”

Otherwise, I will set out to talk about Friendly AI, one of these days, and someone will say: “But it’s a machine; it can’t make choices, because it couldn’t have done anything other than what it did.”

So let’s talk about this word, “could”. Can you play Rationalist’s Taboo against it? Can you talk about “could” without using synonyms like “can” and “possible”?

Let’s talk about this notion of “possibility”. I can tell, to some degree, whether a world is actual or not actual; what does it mean for a world to be “possible”?

I know what it means for there to be “three” apples on a table. I can verify that experimentally, I know what state of the world corresponds it. What does it mean to say that there “could” have been four apples, or “could not” have been four apples? Can you tell me what state of the world corresponds to that, and how to verify it? Can you do it without saying “could” or “possible”?

I know what it means for you to rescue a toddler from the orphanage. What does it mean for you to could-have-not done it? Can you describe the corresponding state of the world without “could”, “possible”, “choose”, “free”, “will”, “decide”, “can”, “able”, or “alternative”?

One last chance to take a stab at it, if you want to work out the answer for yourself...

Some of the first Artificial Intelligence systems ever built, were trivially simple planners. You specify the initial state, and the goal state, and a set of actions that map states onto states; then you search for a series of actions that takes the initial state to the goal state.

Modern AI planners are a hell of a lot more sophisticated than this, but it’s amazing how far you can get by understanding the simple math of everything. There are a number of simple, obvious strategies you can use on a problem like this. All of the simple strategies will fail on difficult problems; but you can take a course in AI if you want to talk about that part.

There’s backward chaining: Searching back from the goal, to find a tree of states such that you know how to reach the goal from them. If you happen upon the initial state, you’re done.

There’s forward chaining: Searching forward from the start, to grow a tree of states such that you know how to reach them from the initial state. If you happen upon the goal state, you’re done.

Or if you want a slightly less simple algorithm, you can start from both ends and meet in the middle.

Let’s talk about the forward chaining algorithm for a moment.

Here, the strategy is to keep an ever-growing collection of states that you know how to reach from the START state, via some sequence of actions and (chains of) consequences. Call this collection the “reachable from START” states; or equivalently, label all the states in the collection “reachable from START”. If this collection ever swallows the GOAL state—if the GOAL state is ever labeled “reachable from START”—you have a plan.

“Reachability” is a transitive property. If B is reachable from A, and C is reachable from B, then C is reachable from A. If you know how to drive from San Jose to San Francisco, and from San Francisco to Berkeley, then you know a way to drive from San Jose to Berkeley. (It may not be the shortest way, but you know a way.)

If you’ve ever looked over a game-problem and started collecting states you knew how to achieve—looked over a maze, and started collecting points you knew how to reach from START—then you know what “reachability” feels like. It feels like, “I can get there.” You might or might not be able to get to the GOAL from San Francisco—but at least you know you can get to San Francisco.

You don’t actually run out and drive to San Francisco. You’ll wait, and see if you can figure out how to get from San Francisco to GOAL. But at least you could go to San Francisco any time you wanted to.

(Why would you want to go to San Francisco? If you figured out how to get from San Francisco to GOAL, of course!)

Human beings cannot search through millions of possibilities one after the other, like an AI algorithm. But—at least for now—we are often much more clever about which possibilities we do search.

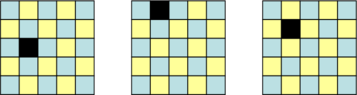

One of the things we do that current planning algorithms don’t do (well), is rule out large classes of states using abstract reasoning. For example, let’s say that your goal (or current subgoal) calls for you to cover at least one of these boards using domino 2-tiles.

The black square is a missing cell; this leaves 24 cells to be covered with 12 dominos.

You might just dive into the problem, and start trying to cover the first board using dominos—discovering new classes of reachable states:

However, you will find after a while that you can’t seem to reach a goal state. Should you move on to the second board, and explore the space of what’s reachable there?

But I wouldn’t bother with the second board either, if I were you. If you construct this coloring of the boards:

Then you can see that every domino has to cover one grey and one yellow square. And only the third board has equal numbers of grey and yellow squares. So no matter how clever you are with the first and second board, it can’t be done.

With one fell swoop of creative abstract reasoning—we constructed the coloring, it was not given to us—we’ve cut down our search space by a factor of three. We’ve reasoned out that the reachable states involving dominos placed on the first and second board, will never include a goal state.

Naturally, one characteristic that rules out whole classes of states in the search space, is if you can prove that the state itself is physically impossible. If you’re looking for a way to power your car without all that expensive gasoline, it might seem like a brilliant idea to have a collection of gears that would turn each other while also turning the car’s wheels—a perpetual motion machine of the first type. But because it is a theorem that this is impossible in classical mechanics, we know that every clever thing we can do with classical gears will not suffice to build a perpetual motion machine. It is as impossible as covering the first board with classical dominos. So it would make more sense to concentrate on new battery technologies instead.

Surely, what is physically impossible cannot be “reachable”… right? I mean, you would think...

Oh, yeah… about that free will thing.

So your brain has a planning algorithm—not a deliberate algorithm that you learned in school, but an instinctive planning algorithm. For all the obvious reasons, this algorithm keeps track of which states have known paths from the start point. I’ve termed this label “reachable”, but the way the algorithm feels from inside, is that it just feels like you can do it. Like you could go there any time you wanted.

And what about actions? They’re primitively labeled as reachable; all other reachability is transitive from actions by consequences. You can throw a rock, and if you throw a rock it will break a window, therefore you can break a window. If you couldn’t throw the rock, you wouldn’t be able to break the window.

Don’t try to understand this in terms of how it feels to “be able to” throw a rock. Think of it in terms of a simple AI planning algorithm. Of course the algorithm has to treat the primitive actions as primitively reachable. Otherwise it will have no planning space in which to search for paths through time.

And similarly, there’s an internal algorithmic label for states that have been ruled out:

worldState.possible == 0

So when people hear that the world is deterministic, they translate that into: “All actions except one are impossible.” This seems to contradict their feeling of being free to choose any action. The notion of physics following a single line, seems to contradict their perception of a space of possible plans to search through.

The representations in our cognitive algorithms do not feel like representations; they feel like the way the world is. If your mind constructs a search space of states that would result from the initial state given various actions, it will feel like the search space is out there, like there are certain possibilities.

We’ve previously discussed how probability is in the mind. If you are uncertain about whether a classical coin has landed heads or tails, that is a fact about your state of mind, not a property of the coin. The coin itself is either heads or tails. But people forget this, and think that coin.probability == 0.5, which is the Mind Projection Fallacy: treating properties of the mind as if they were properties of the external world.

So I doubt it will come as any surprise to my longer-abiding readers, if I say that possibility is also in the mind.

What concrete state of the world—which quarks in which positions—corresponds to “There are three apples on the table, and there could be four apples on the table”? Having trouble answering that? Next, say how that world-state is different from “There are three apples on the table, and there couldn’t be four apples on the table.” And then it’s even more trouble, if you try to describe could-ness in a world in which there are no agents, just apples and tables. This is a Clue that could-ness and possibility are in your map, not directly in the territory.

What is could-ness, in a state of the world? What are can-ness and able-ness? They are what it feels like to have found a chain of actions which, if you output them, would lead from your current state to the could-state.

But do not say, “I could achieve X”. Say rather, “I could reach state X by taking action Y, if I wanted”. The key phrase is “if I wanted”. I could eat that banana, if I wanted. I could step off that cliff there—if, for some reason, I wanted to.

Where does the wanting come from? Don’t think in terms of what it feels like to want, or decide something; try thinking in terms of algorithms. For a search algorithm to output some particular action—choose—it must first carry out a process where it assumes many possible actions as having been taken, and extrapolates the consequences of those actions.

Perhaps this algorithm is “deterministic”, if you stand outside Time to say it. But you can’t write a decision algorithm that works by just directly outputting the only action it can possibly output. You can’t save on computing power that way. The algorithm has to assume many different possible actions as having been taken, and extrapolate their consequences, and then choose an action whose consequences match the goal. (Or choose the action whose probabilistic consequences rank highest in the utility function, etc. And not all planning processes work by forward chaining, etc.)

You might imagine the decision algorithm as saying: “Suppose the output of this algorithm were action A, then state X would follow. Suppose the output of this algorithm were action B, then state Y would follow.” This is the proper cashing-out of could, as in, “I could do either X or Y.” Having computed this, the algorithm can only then conclude: “Y ranks above X in the Preference Ordering. The output of this algorithm is therefore B. Return B.”

The algorithm, therefore, cannot produce an output without extrapolating the consequences of itself producing many different outputs. All but one of the outputs being considered is counterfactual; but which output is the factual one cannot be known to the algorithm until it has finished running.

A bit tangled, eh? No wonder humans get confused about “free will”.

You could eat the banana, if you wanted. And you could jump off a cliff, if you wanted. These statements are both true, though you are rather more likely to want one than the other.

You could even flatly say, “I could jump off a cliff” and regard this as true—if you construe could-ness according to reachability, and count actions as primitively reachable. But this does not challenge deterministic physics; you will either end up wanting to jump, or not wanting to jump.

The statement, “I could jump off the cliff, if I chose to” is entirely compatible with “It is physically impossible that I will jump off that cliff”. It need only be physically impossible for you to choose to jump off a cliff—not physically impossible for any simple reason, perhaps, just a complex fact about what your brain will and will not choose.

Defining things appropriately, you can even endorse both of the statements:

“I could jump off the cliff” is true from my point-of-view

“It is physically impossible for me to jump off the cliff” is true for all observers, including myself

How can this happen? If all of an agent’s actions are primitive-reachable from that agent’s point-of-view, but the agent’s decision algorithm is so constituted as to never choose to jump off a cliff.

You could even say that “could” for an action is always defined relative to the agent who takes that action, in which case I can simultaneously make the following two statements:

NonSuicidalGuy could jump off the cliff.

It is impossible that NonSuicidalGuy will hit the ground.

If that sounds odd, well, no wonder people get confused about free will!

But you would have to be very careful to use a definition like that one consistently. “Could” has another closely related meaning in which it refers to the provision of at least a small amount of probability. This feels similar, because when you’re evaluating actions that you haven’t yet ruled out taking, then you will assign at least a small probability to actually taking those actions—otherwise you wouldn’t be investigating them. Yet “I could have a heart attack at any time” and “I could have a heart attack any time I wanted to” are not the same usage of could, though they are confusingly similar.

You can only decide by going through an intermediate state where you do not yet know what you will decide. But the map is not the territory. It is not required that the laws of physics be random about that which you do not know. Indeed, if you were to decide randomly, then you could scarcely be said to be in “control”. To determine your decision, you need to be in a lawful world.

It is not required that the lawfulness of reality be disrupted at that point, where there are several things you could do if you wanted to do them; but you do not yet know their consequences, or you have not finished evaluating the consequences; and so you do not yet know which thing you will choose to do.

A blank map does not correspond to a blank territory. Not even an agonizingly uncertain map corresponds to an agonizingly uncertain territory.

(Next in the free will solution sequence is “The Ultimate Source”, dealing with the intuition that we have some chooser-faculty beyond any particular desire or reason. As always, the interested reader is advised to first consider this question on their own—why would it feel like we are more than the sum of our impulses?)

- The Ultimate Source by (Jun 15, 2008, 9:01 AM; 79 points)

- Maybe Lying Doesn’t Exist by (Oct 14, 2019, 7:04 AM; 71 points)

- Against Modal Logics by (Aug 27, 2008, 10:13 PM; 70 points)

- The Meaning of Right by (Jul 29, 2008, 1:28 AM; 61 points)

- Heading Toward: No-Nonsense Metaethics by (Apr 24, 2011, 12:42 AM; 55 points)

- Ingredients of Timeless Decision Theory by (Aug 19, 2009, 1:10 AM; 52 points)

- Devil’s Offers by (Dec 25, 2008, 5:00 PM; 50 points)

- Passing the Recursive Buck by (Jun 16, 2008, 4:50 AM; 49 points)

- Timeless Control by (Jun 7, 2008, 5:16 AM; 47 points)

- Voluntary Behavior, Conscious Thoughts by (Jul 11, 2011, 10:13 PM; 47 points)

- Three Fallacies of Teleology by (Aug 25, 2008, 10:27 PM; 39 points)

- Grasping Slippery Things by (Jun 17, 2008, 2:04 AM; 36 points)

- Nonsentient Optimizers by (Dec 27, 2008, 2:32 AM; 35 points)

- Decision theory: An outline of some upcoming posts by (Aug 25, 2009, 7:34 AM; 31 points)

- Fuzzy Boundaries, Real Concepts by (May 7, 2018, 3:39 AM; 27 points)

- Heading Toward Morality by (Jun 20, 2008, 8:08 AM; 27 points)

- Setting Up Metaethics by (Jul 28, 2008, 2:25 AM; 27 points)

- Q: What has Rationality Done for You? by (Apr 2, 2011, 4:13 AM; 18 points)

- Help us Optimize the Contents of the Sequences eBook by (Sep 19, 2013, 4:31 AM; 18 points)

- 's comment on Blanchard’s Dangerous Idea and the Plight of the Lucid Crossdreamer by (Jul 30, 2023, 8:40 PM; 14 points)

- 's comment on Fake Explanations in Modern Science: The Case of Inefficiency by (Jul 24, 2013, 5:38 PM; 12 points)

- 's comment on Counterfactual Mugging by (Mar 19, 2009, 4:41 PM; 11 points)

- 's comment on Formalizing Newcomb’s by (Apr 6, 2009, 4:58 PM; 10 points)

- 's comment on The 5-Second Level by (May 8, 2011, 3:58 AM; 10 points)

- 's comment on Attention Lurkers: Please say hi by (Apr 19, 2010, 1:51 AM; 8 points)

- Repairing Yudkowsky’s anti-zombie argument by (Oct 5, 2011, 11:08 AM; 7 points)

- What is the subjective experience of free will for agents? by (Apr 2, 2020, 3:53 PM; 7 points)

- [SEQ RERUN] Possibility and Could-ness by (Jun 2, 2012, 5:28 AM; 6 points)

- 's comment on Morality is not about willpower by (Oct 8, 2011, 9:39 AM; 6 points)

- Will As Thou Wilt by (Jul 7, 2008, 10:37 AM; 6 points)

- 's comment on Rationality quotes: October 2010 by (Oct 19, 2010, 11:42 PM; 6 points)

- 's comment on Would Your Real Preferences Please Stand Up? by (Aug 10, 2009, 4:43 AM; 6 points)

- 's comment on Is moral duty/blame irrational because a person does only what they must? by (Oct 16, 2021, 10:25 PM; 5 points)

- 's comment on Conceptual Analysis and Moral Theory by (Nov 21, 2014, 2:29 AM; 4 points)

- 's comment on Disguised Queries by (Apr 14, 2012, 9:28 PM; 4 points)

- 's comment on The Smoking Lesion: A problem for evidential decision theory by (Aug 23, 2010, 8:00 PM; 4 points)

- Towards a New Decision Theory for Parallel Agents by (Aug 7, 2011, 11:39 PM; 4 points)

- 's comment on Blanchard’s Dangerous Idea and the Plight of the Lucid Crossdreamer by (Aug 6, 2023, 8:37 PM; 3 points)

- 's comment on Open Thread, September 15-30, 2012 by (Sep 28, 2012, 2:07 PM; 3 points)

- 's comment on An Alien God by (Nov 1, 2009, 10:25 PM; 3 points)

- 's comment on Rationality is Systematized Winning by (Apr 14, 2009, 5:48 PM; 2 points)

- 's comment on Rationality Quotes Thread September 2015 by (Sep 29, 2015, 8:16 PM; 2 points)

- 's comment on Weak foundation of determinism analysis by (Aug 8, 2019, 12:08 AM; 2 points)

- Sofia ACX November 2024 Meetup by (Nov 10, 2024, 1:15 PM; 2 points)

- Voluntary Behavior, Conscious Thoughts by (Jul 11, 2011, 10:13 PM; 2 points)

- Why IQ shouldn’t be considered an external factor by (Apr 4, 2015, 5:58 PM; 2 points)

- 's comment on The First Step is to Admit That You Have a Problem by (Oct 7, 2009, 7:57 PM; 2 points)

- 's comment on Rationality Quotes—June 2009 by (Jun 26, 2009, 3:29 AM; 2 points)

- 's comment on Probability of coming into existence again ? by (Feb 28, 2015, 5:24 PM; 2 points)

- 's comment on Best Nonfiction Writing on Less Wrong by (Nov 25, 2011, 11:46 AM; 2 points)

- 's comment on Discussion: Yudkowsky’s actual accomplishments besides divulgation by (Jun 27, 2011, 3:20 AM; 2 points)

- 's comment on Possibility and Could-ness by (Jun 19, 2008, 9:19 PM; 0 points)

- 's comment on Possibility and Could-ness by (Jun 20, 2008, 5:39 AM; 0 points)

- 's comment on Rationality Quotes Thread September 2015 by (Oct 7, 2015, 5:23 PM; 0 points)

- 's comment on Post Your Utility Function by (Jun 10, 2009, 3:53 PM; 0 points)

- 's comment on Why Bayesians should two-box in a one-shot by (Dec 16, 2017, 10:00 PM; 0 points)

Eliezer, Great articulation. This pretty much sums up my intuition on free will and human capacity to make choices at this stage of our knowledge, too. You made the distinction between physical capability and possibly determined motivation crystal clear.

I feel the obligation to post this warning again: Don’t think “Ohhh, the decision I’ll make is already determined, so I can as well relax and don’t worry too much.” Remember you will face the consequences of whatever you decide so make the best possible choice, maximize utility!

“You are not obliged to complete the work, but neither are you free to evade it” -

Rabbi Tarfon

Paraphrasing my previous comment in another way: determinism is no excuse for you to be sloppy, lazy or unattentive in your decision process.

Well said. The fact of deliberation being deterministic does not obviate the need to engage in deliberation. That would be like believing that running the wrong batch program is just as effective as running the right one, just because there will be some output either way.

Eliezer: I’ll second Hopefully Anonymous; this is almost exactly what I believe about the whole determinism-free will debate, but it’s devilishly hard to describe in English because our vocabulary isn’t constructed to make these distinctions very clearly. (Which is why it took a 2700-word blog post). Roland and Andy Wood address one of the most common and silliest arguments against determinism: “If determinism is true, why are you arguing with me? I’ll believe whatever I’ll believe.” The fact that what you’ll believe is deterministically fixed doesn’t affect the fact that this argument is part of what fixes it.

Roland and Andy, I think you’re misreading this formulation of determinism. One may have the illusion/hallucination of being able to engage in deliberation, or relax. But the analogy is more like a kid thinking they’re playing a game that’s on autoplay mode. The experience of deliberating, the experience of relaxing, the “consequences” are all determined, even if they’re unknowable to the person having these experiences. I’m not saying this is the best model of reality, but at this stage of our knowledge it seems to me to be a plausible model of reality.

No. In your analogy, what the kid does has no causal impact on what their character does in the game. In real life, what you(your brain) does is almost always the cause of what your body does. The two situations are not analogous. Remember, determinism does not mean you lack control over your decisions. Also remember, you just are your brain. There’s no separate “you” outside your brain that exists but lacks control because all your actions are caused by your brain instead.

Hopefully: I’ll thank you not to attribute to me positions that I don’t hold. I assure you I am well aware that all of the abovementioned deciding, yea this very discussion and all of my reasoning, concluding, and thought-pattern fixing, are deterministic processes. Thank you.

Hopefully, I don’t see why you insist on calling deliberation “illusory”. Explaining is not the same as explaining away. Determined is not the same as predetermined. I deliberate not yet knowing what I’ll choose, consider various factors that do in fact determine my choice, and then, deterministically/lawfully, choose. Where’s the illusion? You would seem to be trying to get rid of the rainbow, not just the gnomes.

Eliezer, first (and I think this is an important distinction) I’m saying that human deliberation could be illusory. This is different than saying that it is illusory -as far as I can tell, we don’t know enough to know. I think it’s a distinction worth keeping as a possibility, to the degree that it can help us develop the best models of reality. Of course if human deliberation is 100% illusory, in all points of configuration space, it would seem to be useless knowledge for us, since even those moments of knowing (and then not knowing or forgetting) would be determined.

However, I can think of a scenario where it can be very useful for us to find out if most, but not all moments of human deliberation are determined. It can allow us to rationally put resources into those areas where deliberation can make a positive difference on our persistence odds.

I suppose rather than trying to get rid of the rainbow, I’m trying maximize our flexibility regarding all rainbow viewing traditions, to see if we can maximize the amount of our rainbow viewing time. How much deliberation should Eliezer do, and in what ways? Who else should be deliberating? Should we be assembly line cloning/breeding our best deliberators for this problems? I understand the benefit of well-crafted propaganda, including lines about telling the general population to choose rationality. But I think the best propaganda is an empirical/bayesian question, and can be fairly separate from the best models of reality, which seem to be important to maximizing our persistence odds.

My apologies that this hastily crafted response rambles a bit, but I hope it gives better insight into why I’m encouraging us to stay open to the possibility that large swaths, or all of human deliberation is “illusory”, even while I’m encouraging the best and most efficient possible deliberation into how to best maximize our persistence odds.

Hopefully, I have no idea what you mean by the phrase, “deliberation is illusory”. I do not understand what state of the world corresponds to this being the case. This is not Socratic questioning, I literally have no idea what you’re trying to say.

Hopefully probably means that the only acceptable definitions of deliberation involve choices between real possibilities. To Hopefully you probably sound like someone saying unicorns exist but don’t have horns.

HA could be saying that deliberation may be effectively epiphenomenal—that it only ever rationalizes conclusions already arrived at nondeliberatively (“predetermined”). This is either completely false (if the nondeliberative process doesn’t arrive at right answers more often than chance) or completely useless (if it does).

Hopefully: You seem to be confusing the explicit deliberation of verbal reasoning, much of which is post-hoc or confabulation and not actually required to determine people’s actions (rather it is determined by their actions), with the implicit deliberation of neural algorithms, which constitute the high level description of the physics that determines people’s actions, the description which is valid on the level of description of the universe where people exist at all.

Hopefully: My suggestion is, that it is the use of the metaphor “illusion”, which is unfortunate. In the process—Search Find (have a beer) Execute there is no room for illusion. Just as David Copperfield works very hard whilst making illusions but is himself under no illusion. In other words “illusion” is an out of process perspective. It is in the “I” of the beholder. You hope(fully) expect that the search process can be improved by the intervention of “I”. Why should that be? Would the search process be improved by a coin flip? In other words dissolving “free will” dissolves the “user-illusion” of “Eye”. And this plays havoc with your persistence odds. You want your illusion to persist?

Michael, I don’t think I’m “confusing” the explicit deliberation of verbal reasoning with the implicit deliberation of neural algorithms any more than Eliezer is in his various recent posts and admonitions on this topic. But I think it’s a useful distinction you’re bringing up.

Nick, I’m going a little farther than that- I’m saying that the deliberation, that the rationalizing of conclusions, as you put it, may be illusory in that there may be no personal agency in that process either. In Eliezer’s terms, it would be impossible for one to rationalize that process any differently, or to choose not to rationalize that process.

Eliezer, what I mean isn’t anything outside of your original post we’re all commenting on. As you summed up quite well “A blank map does not correspond to a blank territory. Not even an agonizingly uncertain map corresponds to an agonizingly uncertain territory.” The idea that one is choosing one’s route AND that one could have chosen differently may be illusory. It’s a model of reality, and I’m not sure it’s the best model. But I don’t think it should be dismissed simply because it undermines the way some people want to create status hierarchies (personal moral culpability), which I think is an unhelpful undercurrent in some of these discussions.

It would seem I have failed to make my point, then.

Choosing does not require that it be physically possible to have chosen differently.

Being able to say, “I could have chosen differently,” does not require that it be physically possible to have chosen differently. It is a different sense of “could”.

I am not saying that choice is an illusion. I am pointing to something and saying: “There! Right there! You see that? That’s a choice, just as much as a calculator is adding numbers! It doesn’t matter if it’s deterministic! It doesn’t matter if someone else predicted you’d do it or designed you to do it! It doesn’t matter if it’s made of parts and caused by the dynamics of those parts! It doesn’t matter if it’s physically impossible for you to have finally arrived at any other decision after all your agonizing! It’s still a choice!”

That’s a matter of definitions, not fact.

The algorithm has to assume many different possible actions as having been taken, and extrapolate their consequences, and then choose an action whose consequences match the goal … The algorithm, therefore, cannot produce an output without extrapolating the consequences of itself producing many different outputs.

It seems like you need to talk about our “internal state space”, not our internal algorithms—since as you pointed out yourself, our internal algorithms might never enumerate many possibilities (jumping off a cliff while wearing a clown suit) that we still regard as possible. (Indeed, they won’t enumerate many possibilities at all, if they do anything even slightly clever like local search or dynamic programming.)

Otherwise, if you’re not willing to talk about a state space independent of algorithms that search through it, then your account of counterfactuals and free will would seem to be at the mercy of algorithmic efficiency! Are more choices “possible” for an exponential-time algorithm than for a polynomial-time one?

Hmm, it seems my class on free will may actually be useful.

Eliezer: you may be interested to know that your position corresponds almost precisely to what we call classical compatibilism. I was likewise a classical compatibilist before taking my course—under ordinary circumstances, it is quite a simple and satisfactory theory. (It could be your version is substantially more robust than the one I abandoned, of course. For one, you would probably avoid the usual trap of declaring that agents are responsible for acts if and only if the acts proceed from their free will.)

Hopefully Anonymous: Are you using Eliezer’s definition of “could”, here? Remember, Eliezer is saying “John could jump off the cliff” means “If John wanted, John would jump off the cliff”—it’s a counterfactual. If you reject this definition as a possible source of free will, you should do so explicitly.

The problem I have with this idea that choices are deterministic is that people end up saying things such as:

Don’t think “Ohhh, the decision I’ll make is already determined, so I can as well relax and don’t worry too much.”

In other words: “Your decision is determined, but please choose to decide carefully.” Hmmm… slight contradiction there.

The problem I have with the idea that choices are determined is that it doesn’t really explain what the hell we are doing when we are “thinking hard” about a decision. Just running an algorithm? But if everything we ever do in our minds is running an algorithm, why does “thinking hard” feel different from, let’s say, walking home in “autopilot mode”? In both cases there are estimations of future probabilities and things that “could” happen, but in the second case we feel it’s all done in “automatic”. Why does this “automatic” feel different from the active “thinking hard”?

The two different algorithms “feel” different because they have different effects on our internal mental state, particularly the part of our mental state that is accessible to the part of us that describes how we feel (to ourselves as well as others).

Doly: Why does fire feel different from ice if perceiving them both is just something done in our minds? They are both “something” done in our minds, but they are different things.

Hopefully: It’s obvious that if you had been a sufficiently different system you WOULD have done differently. With respect to running or not from the orphanage, how different might mean one more or less neuron or might mean 10^10th of your 10^14th synapses had strengths more than 12% greater. With respect to jumping off the cliff it might mean no optic nerve. For falling after having jumped, it might mean not being a balloon or not having befriended the right person who would otherwise have been there to catch you with his whip before you fell very far. It’s also obvious that if your decision could have been different without you being a very different system, especially if a different decision would have been made by someone with identical memories, particularly if they would have identical memories after the fact, then there is an important sense in which they are not to blame. As for what if they could have behaved differently even if they were the same system, such questions seem to show ignorance of what the word “system” means. A system is all the relevant math. Different inputs can’t correspond to different outputs. Of course, in this strong sense of ‘system’ there is also no person distinct from the fire. Still, even a more moderate question such as ‘could a system implementing the algorithm that the billiard ball model of you is best approximated by have acted differently’ shows confusion. A given algorithm does what it does and could not do otherwise. Blame attaches to not being the right algorithm.

The type of possibility you describe is just a product of our ignorance about our own or others psychology. If I don’t understand celestial mechanics I might claim that Mars could be anywhere in its orbit at any time. If somebody then came along and taught me celestial mechanics I could then argue that Mars could still be anywhere if it wanted to. This is just saying that Mars could be anywhere if Mars was different. It gets you exactly nothing.

Eliezer: What lame challenge are you putting up, asking for a state of the world which corresponds to possibility? No one claims that possibility is a state of the world.

An analogous error would be to challenge those of us who believe in musical scales to name a note that corresponds to a C major scale.

Jim Baxter: Good luck to you. So far as I can tell, a majority here take their materialism as a premise, not as something subject to review.

“What concrete state of the world—which quarks in which positions—corresponds to “There are three apples on the table, and there could be four apples on the table”? Having trouble answering that? Next, say how that world-state is different from “There are three apples on the table, and there couldn’t be four apples on the table.”″

For the former: An ordinary kitchen table with three apples on it. For the latter: An ordinary kitchen table with three apples on it, wired to a pressure-sensitive detonator that will set off 10 kg of C4 if any more weight is added onto the table.

“But “I could have a heart attack at any time” and “I could have a heart attack any time I wanted to” are nonetheless not exactly the same usage of could, though they are confusingly similar.”

They both refer to possible consequences if the initial states were changed, while still obeying a set of constraints. The first refers to a change in initial external states (“there’s a clot in the artery”/”there’s not a clot in the artery”), while the second refers to a change in initial internal states (“my mind activates the induce-heart-attack nerve signal”/”my mind doesn’t activate the induce-heart-attack nerve signal”). Note that “could” only makes sense if the initial conditions are limited to a pre-defined subset. For the above apple-table example, in the second case, you would say that the statement “there could be four apples on the table” is false, but you have to assume that the range of initial states the “could” refers to don’t refer to states in which the detonator is disabled. For the heart-attack example, you have to exclude initial states in which the Mad Scientist Doctor (tm) snuck in in the middle of the night and wired up a deliberation-based heart-attack-inducer.

Dude. Eliezer.

Every time I actually read your posts, I find them quite interesting.

But I rarely do, because the little “oh I was so brilliant as a kid that I already knew this, now I will explain it to YOU! Lucky you!” bits with which you preface every single post make me not interested in reading your writing.

I wouldn’t write this comment if I didn’t think you were a smart guy who has something to say

James Baxter: I think that was in poor taste.

Doly: My suggestion would be to keep reading and thinking about this. There is no contradiction, but one has to realize that everything is inside the dominion of physics, even conversations and admonitions. That is, reading some advice, weighing it, and choosing to incorporate it (or not) into one’s arsenal are all implemented by physical processes, therefore none are meta. None violate determinism.

Robin Z: I have not yet seen an account of classical compatibilism (including the one you linked) that was not rife with (what I consider) naive language. I don’t mean that impolitely, I mean that the language used is not up to the task. The first concept that I dispense with is “free,” and yet the accounts I have read seem very interested in preserving and reconciling the “free” part of “free will.” So, while I highly doubt that CC is equivalent to my view in the first place, I’m still curious about what view you adopted to replace it.

Hopefully: Are you trying to say that personal agency is illusory? If I say, “The human that produced these words contains the brain which executed the process which led to action (A),” that is a description of personal agency. That does not preclude the concept “person” itself being a massively detailed complex, rather than an atomic entity. I, and I expect others here, do not feel a pressing need to contort our conversational idioms thusly, to accurately reflect our beliefs about physics and cognition. That would get tiresome.

Eliezer, no you made your point quite clearly, and I think I reflect a clear understanding of that point in my posts.

“I am not saying that choice is an illusion. I am pointing to something and saying: “There! Right there! You see that? That’s a choice, just as much as a calculator is adding numbers! It doesn’t matter if it’s deterministic! It doesn’t matter if someone else predicted you’d do it or designed you to do it! It doesn’t matter if it’s made of parts and caused by the dynamics of those parts! It doesn’t matter if it’s physically impossible for you to have finally arrived at any other decision after all your agonizing! It’s still a choice!”″

It seems to me that’s an arbitrary claim grounded in aesthetics. You could just as easily say “You see that? That’s not a choice, just as much as a calculator is adding numbers! It doesn’t matter if it’s deterministic! It doesn’t matter if someone else predicted you’d do it or designed you to do it! It doesn’t matter if it’s made of parts and caused by the dynamics of those parts! It doesn’t matter if it’s physically impossible for you to have finally arrived at any other decision after all your agonizining! It’s not a choice!”″

Doly wrote “The problem I have with the idea that choices are determined is that it doesn’t really explain what the hell we are doing when we are “thinking hard” about a decision. Just running an algorithm? But if everything we ever do in our minds is running an algorithm, why does “thinking hard” feel different from, let’s say, walking home in “autopilot mode”? In both cases there are estimations of future probabilities and things that “could” happen, but in the second case we feel it’s all done in “automatic”. Why does this “automatic” feel different from the active “thinking hard”?”

Good questions, and well worth exploring. At this stage quality neuroscience research can probably help us answer a lot of these determinism/human choice questions better than blog comments debate. It’s one thing to say human behavior is determined at the level of quantum mechanics. What’s traditionally counterintuitive (as shown by Jim Baxter’s quotes) is how determined human behavior is (despite instances of the illusion of choice/free will) at higher levels of cognition. I think it’s analogous to how our vision isn’t constructed at higher levels of cognition in the way we tend to intuit that it is (it’s not like a movie camera).

Andy Wood: So, while I highly doubt that CC is equivalent to my view in the first place, I’m still curious about what view you adopted to replace it.

I suspect (nay, know) my answer is still in flux, but it’s actually fairly similar to classical compatibilism—a person chooses of their own free will if they choose by a sufficiently-reasonable process and if other sufficiently-reasonable processes could have supported different choices. However, following the example of Angela Smith (an Associate Professor of Philosophy at the University of Washington), I hold that free will is not required for responsibility. After all, is it not reasonable to hold someone responsible for forgetting an important duty?

What do you mean, when you say a thing is a choice? What properties must the thing have for you to give it that label?

I really struggled with reconciling my intuitive feeling of free will with determinism for a while. Finally, when I was about 18, my beliefs settled in (I think) exactly this way of thinking. My sister still doesn’t accept determinism. When we argue, I always emphasize: “Just because reality is deterministic, that doesn’t mean we stop choosing!”

What properties must a human visual system that works like a a movie camera have? Properties that apparently don’t exist in the actual human visual system. Similarly the popular model of human choice tied to moral responsibility (a person considers options, has the ability to choose the “more moral” or the “less moral” option, and chooses the “more moral” option) may not exist in actual working human brains. In that sense it’s reasonable to say “if it’s detetministic, if you’re designed to do it, if it’s made of parts and caused by the dynamics of those parts, if it’s physically impossible for you to have finally arrived at any other decision after all your agonizing” it’s not a choice. It’s an observable phenonenon in nature, like the direction a fire burns, the investments made by a corporation, or the orbital path of Mars. But singling out that phenomenon and calling it “choice” may be like calling something a “perpetual motion machine” or an “omnipotent god”. The word usage may obfuscate the phenomenon by playing on our common cognitive biases. I think it can be tempting for those who wish to construct status hierarchies off of individual moral “choice” histories, or who fear, perhaps without rational basis, that if they stop thinking about their personal behavior in terms of making the right “choices” they’ll accomplish less, or do things they’ll regret. Or perhaps it’s just an anaesthetic model of reality for some.

Still, I think the best neuroscience research already demonstrates how wide swaths of our intuitive understanding of “choice” are as inaccurate as our intuitive understanding of vision and other experiential phenomenon.

anaesthetic = unaesthetic.

HA: This pretty much sums up my intuition on free will and human capacity to make choices

Jadagul: this is almost exactly what I believe about the whole determinism-free will debate

kevin: Finally, when I was about 18, my beliefs settled in (I think) exactly this way of thinking.

Is no-one else throwing out old intuitions based on these posts on choice & determinism? -dies of loneliness-

The note about possibilities being constrained by what you’ll actually choose pushed me to (I think) finally dissolve the mystery about the “action is chosen by self-prediction” view, that tries to avoid utility formalism. At a face value, it’s kind of self-referentially: what makes a good prediction then? If it’s good concentration of probability, then it’s easy to “predict” some simple action with certainty, and to perform it. Probabilities of possible futures are constrained both by knowledge about the world, and by knowledge about your goals. Decision-making is the process of taking the contribution of the goals into account, that updates the initial assessment of probabilities (“car will run me over”) with one that includes the action you’ll take according to your goals (“I’ll step to the side, and the car will move past me”). But these probabilities are not predictions. You don’t choose the action probabilistically, based on distribution that you’ve made, you choose the best one. The value that is estimated has probabilistic properties, because axioms of the probability theory hold for it, but some of the normal intuitions about probability as belief or probability as frequency don’t apply to it. And the quality of the decision-making is in the probability that corresponded to actual action, just as the quality of belief is in what probability corresponded to actual state of the world. The difference is that with normal beliefs, you don’t determine the actual fact that they are measuring; but with decision-making, you both determine the fact, and form a “belief” about it. And in this paradoxical situation, you still must remain rational about the “belief”, and not confuse it with the territory: “belief” is probabilistic, and ranges over possibilities, while the fact is single, and (!) it’s determined by the “belief”.

If you mean “free will is one of the easier questions to dissolve, or so I found it as a youngster,” personally, I find this interesting and potentially useful (in that it predicts what I might find easy) information. I don’t read any bragging here, just a desire to share information, and I don’t believe Eliezer intends to brag.

We can’t represent ourselves in our deterministic models of the world. If you don’t have the ability to step back and examine the model-building process, you’ll inevitably conclude that your own behavior cannot be deterministic.

The key is to recognize that even if the world is deterministic, we will necessarily perceive uncertainties in it, because of fundamental mathematical limits on the ability of a part to represent the whole. We have no grounds for saying that we are any more or less deterministic than anything else—if we find deterministic models useful in predicting the world, we should use them, and assume that they would predict our own actions, if we could use them that way.

Eliezer said:

I am not saying that choice is an illusion. I am pointing to something and saying: “There! Right there! You see that? That’s a choice, just as much as a calculator is adding numbers! It doesn’t matter if it’s deterministic! It doesn’t matter if someone else predicted you’d do it or designed you to do it! It doesn’t matter if it’s made of parts and caused by the dynamics of those parts! It doesn’t matter if it’s physically impossible for you to have finally arrived at any other decision after all your agonizing! It’s still a choice!”

--

Does it not follow from this that if I installed hardware into your brain that completely took control of your brain and mapped my thoughts onto your brain (and the deliberations in your brain would be ones that I initiated) that you would still be choosing and still be morally responsible? If I decided to kill someone and then forced you to carry out the murder, you would be morally responsible. I find this hard to accept.

Joseph Knecht: Why do you think that the brain would still be Eliezer’s brain after that kind of change?

(Ah, it’s so relaxing to be able to say that. In the free will class, they would have replied, “Mate, that’s the philosophy of identity—you have to answer to the ten thousand dudes over there if you want to try that.”)

Robin, I don’t think “whose brain it is” is really a meaningful and coherent concept, but that is another topic.

My general point was that Eliezer seemed to be saying that certain things occurring in his brain are sufficient for us to say that he made a choice and is morally responsible for the choice. My example was intended to show that while that may be a necessary condition, it is not sufficient.

As for what I actually believe, I think that while the notions of choice and moral responsibility may have made sense in the context in which they arose (though I have strong doubts because that context is so thoroughly confused and riddled with inconsistencies), they don’t make sense outside of that context. Freewill and choice (in the west at least) mean what they mean by virtue of their place in a conceptual system that assumes a non-physical soul-mind is the ultimate agent that controls the body and that what the soul-mind does is not deterministic.

If we give up that notion of a non-physical, non-deterministic soul-mind as the agent, the controller of the body, the thing that ultimately makes choices and is morally responsible (here or in the afterlife), I think we must also give up concepts like choice and moral responsibility.

That is not to say that they won’t be replaced with better concepts, but those concepts will relate to the traditional concepts of choice and moral responsibility as heat relates to caloric.

Joseph Knecht: I think you’re missing the point of Eliezer’s argument. In your hypothetical, to the extent Eliezer-as-a-person exists as a coherent concept, yes he chose to do those things. Your hypothetical is, from what I can tell, basically, “If technology allows me to destroy Eliezer-the-person without destroying the outer, apparent shell of Eliezer’s body, then Eliezer is no longer capable of choosing.” Which is of course true, because he no longer exists. Once you realize that “the state of Eliezer’s brain” and “Eliezer’s identity” are the same thing, your hypothetical doesn’t work any more. Eliezer-as-a-person is making choices because the state of Eliezer’s brain is causing things to happen. And that’s all it means.

Jadagul: No, I think what Joseph’s saying is that all of the language of free will is inherently in the paradigm of non-real dualism, and that to really make meaningful statements we ultimately have to abandon it.

To me, the issue of “free will” and “choice” is so damn simple.

Repost from Righting a Wrong Question:

I realized that when people think of the free will of others, they don’t ask whether this person could act differently if he wanted. That’s a Wrong Question. The real question is, “Could he act differently if I wanted it? Can he be convinced to do something else, with reason, or threats, or incentives?”

From your own point of view that stands between you and being able to rationally respond to new knowledge makes you less free. This includes shackles, threats, bias, or stupidity. Wealth, health, knowledge make you more free. So for yourself, you can determine how much free will you have by looking at your will and seeing how free it is. Can you, as Eliezer put it, “win”?

I define free will by combining these two definitions. A cleptomaniac is a prisoner of his own body. A man who can be scared into not stealing is free to a degree. A man who can swiftly and perfetly adapt to any situation, whether it prohibits stealing, requires it, or allows it, is almost free. A man becomes truly free when he retains the former abilities, and is allowed to steal, AND has the power to change the situation any way he wants.

About choices: what is the criterion by which new ontological primitives are to be added?

Jadagul: I’m saying that Eliezer’s explanation of what a choice is is not a sufficient condition. You suggested some additional constraints, which I would argue may be necessary but are still not sufficient conditions for a choice occurring.

My key point, though, as Schizo noted, was that I don’t think the concept should be salvaged, any more than phlogiston or caloric should have been salvaged.

Joesph: I don’t think I added more constraints, though it’s a possibility. What extra constraints do you think I added?

As for not salvaging it, I can see why you would say that, but what word should be used to take its place? Mises commented somewhere in On Human Action that we can be philosophical monists and practical dualists; I believe that everything is ultimately reducible to (quasi?-)deterministic quantum physics, but that doesn’t mean that’s the most efficient way to analyze most situations. When I’m trying to catch a ball I don’t try to model the effect of the weak nuclear force on the constituent protons. When I’m writing a computer program I don’t even try to simulate the logic gates, much less the electromagnetic reactions that cause them to function. And when I’m dealing with people it’s much more effective to say to myself, “given these options, what will he choose?” This holds even though I could in principle, were I omniscient and unbounded in computing power, calculate this deterministically from the quantum state of his brain.

Or, in other words, we didn’t throw out Newtonian mechanics when we discovered Relativity. We didn’t discard Maxwell when we learned about quantum electrodynamics. Why should this be different?

Joseph—“Choice” is, I should think, more like “fire” and “heat” than like “phlogiston” and “caloric”. We have abandoned the last two as outdated scientific theories, but have not abandoned the first two even though they are much older concepts, presumably because they do not represent scientific theories but rather name observable mundane phenomena.

@Jagadul:

by “constraints”, I meant that Eliezer specified only that some particular processes happening in the brain are sufficient for choice occurring, which my example refuted, to which you added the ideas that it is not mere happening in the brain but also the additional constraints entailed by concepts of Eliezer-the-person and body-shell-of-Eliezer and that the former can be destroyed while the latter remains, which changes ownership of the choice, etc.

Anyway, I understand what you’re saying about choice as a higher-level convenience term, but I don’t think it is helpful. I think it is a net negative and that we’d do better to drop it. You gave the thought, “given these options, what will he choose?”, but I think the notion of choice adds nothing of value to the similar question, “given these options, what will he do?” You might say that it is different, since a choice can be made without an action occurring, but then I think we’d do better to say not “what will he choose?” but something more like “what will he think?”, or perhaps something else depending on the specifics of the situation under consideration.

I believe there’s always a way of rephrasing such things so as not to invoke choice, and all that we really give up is the ability to talk about totally generic hypothetical situations (where it isn’t specified what the “choice” is about). Whenever you flesh out the scenario by specifying the details of the “choice”, then you can easily talk about it more accurately by sidestepping the notion of choice altogether.

I don’t think that “choice” is analogous to Newtonian mechanics before relativity. It’s more akin to “soul”, which we could have redefined and retrofitted in terms of deterministic physical processes in the brain. But just as it makes more sense to forget about the notion of a soul, I think it makes more sense to forget about that of “choice”. Just as “soul” is too strongly associated with ideas such as dualism and various religious ideas, “choice” is too strongly associated with ideas such as non-determinism and moral responsibility (relative to some objective standard of morality). Instead of saying “I thought about whether to do X, Y, or Z, then choose to do X, and then did X”, we can just say “I thought about whether to do X, Y, or Z, then did X.”

@Constant:

I think “choice” is closer to “caloric” than “heat”, because I don’t believe there is any observable mundane phenomenon that it refers to. What do you have in mind that cannot be explained perfectly well without supposing that a “choice” must occur at some point in order to explain the observed phenomenon?

What cannot be explained perfectly well without supposing “heat” exists, if you’re willing to do everything at the molecular level?

At time t=0, I don’t know what I’ll do. At t=1, I know. At t=2, I do it. I call this a “choice”. It’s not strictly necessary, but I find it really useful to have a word for this.

Nick, your example confuses more than it clarifies. What exactly is the choice? Brain processes that occur in 0 < t < 1? Brain processes occurring in that slice that have certain causal relations with future actions? Conscious brain processes occurring such that...? Conscious brain processes occurring such that … which are initiated by (certain) other brain processes?

You speak as if “choice” means something obvious that everybody understands, but it only has such a meaning in the sense that everybody knows what is meant by “soul” (which refers to a non-existent thing that means something different to practically everybody who uses it and usually results in more confusion than clarification).

I am “grunching.” Responding to the questions posted without reading your answer. Then I’ll read your answer and compare. I started reading your post on Friday and had to leave to attend a wedding before I had finished it, so I had a while to think about my answer.

>Can you talk about “could” without using synonyms like “can” and “possible”?

When we speak of “could” we speak of the set of realizable worlds [A’] that follows from an initial starting world A operated on by a set of physical laws f.

So when we say “I could have turned left at the fork in the road.” “Could” refers to the set of realizable worlds that follow from an initial starting world A in which we are faced with a fork in the road, given the set of physical laws. We are specifically identifying a sub-set of [A’]: that of the worlds in which we turned left.

This does not preclude us from making mistakes in our use of could. One might say “I could have turned left, turned right, or started a nuclear war.” The options “started a nuclear war” may simply not be within the set [A’]. It wasn’t physically realizable given all of the permutations that result from applying our physical laws to our starting world.

If our physical laws contain no method for implementing free will and no randomness, [A’] contains only the single world that results from applying the set of physical laws to A. If there is randomness or free will, [A’] contains a broader collection of worlds that result from applying physical laws to A...where the mechanisms of free will or randomness are built into the physical laws.

I don’t mean “worlds” in the quantum mechanics sense, but as a metaphor for resultant states after applying some number of physical permutations to the starting reality.

Why can a machine practice free will? If free will is possible for humans, then it is a set of properties or functions of the physical laws (described by them, contained by them in some way) and a machine might then implement them in whatever fashion a human brain does. Free will would not be a characteristic of A or [A’], but the process applied to A to reach a specific element of [A’].

So...I think I successfully avoided using reference to “might” or “probable” or other synonyms and closely related words.

now I’ll read your post to see if I’m going the wrong way.

Hmm. I think I was working in the right direction, but your procedural analogy let you get closer to the moving parts. But I think “reachability” as you used it and “realizable” as I used it (or was thinking of it) seem to be working along similar lines.

It seems, that a lot of problems here stem from the fact that a lot of existing language is governed by the intuition of non-deterministic world. Common usage of words “choice”, “could”, “deliberation” etc. assume non-deterministic universe where state of “could be four apples” is actually possible. If our minds had easier time grasping that deliberation and action are phenomenons of the same grade, that action stems from deliberation, but there is no question of being able to “choose differently”, that existence deliberation itself is itself predetermined, we would have far fewer comments in this thread :) And Andy and Roland wouldn’t have to post the warnings and Hopeful wouldn’t have to struggle with “illusion of choice”. It seems a lot of comments here are laboring under misapprehension, that “if I knew that I lived in deterministic world, I would be able to forgo all the moral consideration and walk away from the orphanage”, where while this is definitely the case (a universe where you make such a choice would have to accommodate all the states leading to the action of walking away), nevertheless in the universe where you step into the fire to save a kid there is no state of you walking away anywhere.

Robin Z: thank you for enlightening me to formal classification of free will/determinism positions. As far as I know, the modern state of knowledge seems to supply strong evidence of us living in a deterministic universe. Once we take this as a fact, it seems to me the question of “free will” becomes more of a theological issue then a rational one.

this whole discussion gave me a bad case of gas...

Joseph Knecht: It is a clash of intuitions, then? I freely admit that I have seen no such account either, but nor have I seen the kind of evidence which puts “soul” on shaky grounds. And “fire” is comparably ancient to “soul”, and still exists.

In fact, “fire” even suggests an intermediate position between yours and that which you reject: chemically, oxidation reactions like that of fire show up all over the place, and show that the boundary between “fire” and “not fire” is far from distinct. Would it be surprising were it found that the boundary between the prototypical human choices Eliezer names and your not-choices is blurry in a similar fashion?

Robin Z:

I think it is not only a clash of intuitions, since the success rates of pre-scientific theory and folk psychology are poor. This should urge caution in keeping concepts that seem to give rise to much confusion. I would argue that the default attitude towards pre-scientific concepts that have been shrouded in confusion for thousands of years, with still no clarity in sight, should be to avoid them when possible.

When you say that you haven’t seen evidence that puts “soul” on shaky grounds, do you mean that assuming determinism and what we know of human physiology that you believe there are still good reasons for positing the existence of a soul? If so, please explain what you mean by the term and why you think it is still a valuable concept. I think the notion of “soul” arose out of ignorance about the nature of living things (and how human beings were different from non-humans in particular) and that it not only serves no positive purpose but causes confusion, and I suspect that “choice” would never have arisen in anything like the form it did if we were not also confused about things like “free will” and the nature of thought.

Regarding “fire” and that it persists as a term, the only aspects of fire that continue to exist from ancient times are descriptions of its visual appearance and its obvious effects (that is, just the phenomenology of fire). Everything else about the concept has been abandoned or re-explained. Since the core of the concept (that it has the distinctive visual appearance it does and “it burns stuff”) remain, it is reasonable to keep the term and redefine the explanation for the core aspects of the concept.

The case with choice is quite different, as the phenomenology is much more complex, it is less direct, and it is “mental” and not visual (and thus much more likely to be confused/confusing). Things like “fire” and “thunder” and “rain” and “sun” can easily be re-explained since the phenomenology was reasonably accurate and that was the basis for the concept, but we don’t all agree on what is meant by choice or what the concept is supposed to explain.

Eliezer:

If determinism is true, what is the difference between “I could reach state X by taking action Y, if I wanted” and “I could reach state X by taking action Y, if 1=2″?

If determinism is true, then I couldn’t have wanted to do X, just as it couldn’t have been the case that 1=2, so the conditional is vacuously true, since the antecedent is false and must be false.

This doesn’t seem to me like a plausible explanation of possibility or could-ness, unless you can explain how to distinguish between “if I wanted” and “if 1=2″ without mentioning possible worlds or possibility or even reachability (since reachability is what you are defining).

“I” is a fuzzy term, so it is coherent to imagine an entity that is Joseph Knecht except he doesn’t want to save children from burning orphanages, unlike 1=2.

Knecht, it’s immediately obvious that 1 != 2, but you don’t know which of your decisions is determined until after you determine it. So while it is logically impossible (ignoring quantum branching) that you will choose any of your options except one, and all but one of your considered consequences is counterfactual in a way that violates the laws of physics, you don’t know which option is the real one until you choose it.

Apart from that, no difference. Like I said, part of what goes into the making of a rationalist is understanding what it means to live in a lawful universe.

No, it is not logically impossible—it would be impossible only if we insist that there are no random elements in time. We need not invoke ‘quantum branching’ to imagine a universe that is not deterministic.

Again, this is wrong, because it is not known that the laws of physics permit one and only one outcome given an initial state.

Joseph Knecht: When you say that you haven’t seen evidence that puts “soul” on shaky grounds, [...]

Sorry, poor wording—please substitute “but nor have I seen evidence against ‘choice’ of the kind which puts ‘soul’ on shaky grounds.” I am familiar with many of the neurological arguments against souls—I mentioned the concept because I am not familiar with any comparable evidence regarding choice. (Yes, I have heard of the experiments which show nervous impulses towards an action prior to the time when the actor thought they decided. That’s interesting, but it’s no Phineas Gage.)

This should urge caution in keeping concepts that seem to give rise to much confusion.

Well, I’ll give you that. Though I am not ready to drop the concept of choice, I do admit that, among some people, it can lead to confusion. However, it does not seem to confuse all that many, and the concept of choice appears to be a central component of what I would consider a highly successful subject and one which I’m nowhere near ready to toss into the trash—economics.

I don’t think reachable is permissible in the game, since reach-able means able to be reached, or possible to be reached.

Possibility is synonymous with to be able, so any term suffixed with -able should be forbidden.

The reachability explanation of possibility is also just one instance of possibility among many. to be able (without specifying in what manner) is the general type, and able to be reached is one particular (sub-) type of possibility. The more traditional understanding of possibility is able to exist, but others have been used too, such as able to be conceived, able to be done, able to be caused to exist, etc.

bump

Joseph, I told you how to compute “reachable” so it doesn’t matter if you relabel the concept “fizzbin”. First, all actions are labeled fizzbin. Next, the reliable consequence of any fizzbin state of the world is labeled fizzbin (and we keep track of any actions that were labeled fizzbin along the way). If the goal state is ever labeled fizzbin, the actions labeled fizzbin on that pathway are output.

That’s how we do it in Artificial Intelligence, at least in the first undergraduate course.

And the analogous internal perception of an algorithm that computes fizzbin-ness, is what humans call “could”. This is my thesis. It is how you get able-ness from computations that take place on transistors that do not themselves have able-ness or possibilities, but only follow near-deterministic lines.

Can you talk about “could” without using synonyms like “can” and “possible”? …. Can you describe the corresponding state of the world without “could”, “possible”, “choose”, “free”, “will”, “decide”, “can”, “able”, or “alternative”?

My point being that you set out to explain “could” without “able” and you do it by way of elaboration on a state being “able to be reached”.

What you decide to label the concept does not change the fact that the concept you’ve decided upon is a composite concept that is made up of two more fundamental concepts: reaching (or transitioning to) and possibility.

You’ve provided 1 sense of possibility (in terms of reachability), but possibility is a more fundamental concept than “possible to be reached”.

I don’t think “choice” is a central concept to economics. It seems pretty easy to me to reimagine every major economic theory of which I’m aware without “choosing” occuring.

Knecht, for “able to be reached” substitute “labeled fizzbin”. I have told you when to label something fizzbin. The labeling algorithm does not make use of the concept of “possibility”, but it does make use of surgery on causal graphs (the same sort of surgery that is involved in computing counterfactuals); you must have a modular model of the world in which you can ask, “If by fiat node A had value a1, what value would its descendant node B (probably) take on?” This well-specified computation does not have to be interpreted as indicating physical possibility, and in fact, in all but one cases, the world thus computed will not be realized.

The algorithm does use a list of actions, but you do not have to interpret these actions as physically possible (all except one will end up not being taken). I have simply told you flatly to label them “fizzbin” as part of this useful optimization algorithm.

Eliezer, my point was that you dedicated an entire follow-up post to chiding Brandon, in part for using realizable in his explanation since it implicitly refers to the same concept as could, and that you committed the same mistake in using reachable.

Anyway, I guess I misunderstood the purpose of this post. I thought you were trying to give a reductive explanation of possibility without using concepts such a “can”, “could”, and “able”. If I’ve understood you correctly now, that wasn’t the purpose at all: you were just trying to describe what people generally mean by possibility.

Joseph Knecht, Brandon put “realizability” in the territory, whereas Eliezer put “reachability” in the map. Compare and contrast:

Brandon: When we speak of “could” we speak of the set of realizable worlds [A’] that follows from an initial starting world A operated on by a set of physical laws f.

Eliezer: We’ve previously discussed how probability is in the mind… possibility is also in the mind.

It is not the case that Eliezer is criticizing Brandon for the same mistake that Eliezer made himself.

Well, I’m giving up on explaining to Knecht, but if anyone else has a similar misunderstanding (that is, Knecht’s critique seems to make sense to them) let me know and I’ll try harder.

I have constructed fizzbin out of deterministic transistors. The word “reachable” is a mere collection of nine ASCII characters, ignore it if you wish.

Cyan: I think your quibble misses the point. Eliezer’s directions were to play the rationality taboo game and talk about possibility without using any of the forbidden concepts. His explanation failed that task, regardless of whether either he or Brandon were referring to the map or the territory. (Note: this point is completely unrelated to the specifics of the planning algorithm.)

I’ll summarize my other points later. (But to reiterate the point that Eliezer doesn’t get and pre-empt anybody else telling me yet again that the label is irrelevant, I realize the label is irrelevant, and I am not talking about character strings or labels at all.)

Hopefully Anonymous writes: I don’t think “choice” is a central concept to economics. It seems pretty easy to me to reimagine every major economic theory of which I’m aware without “choosing” occuring.

Well, okay. Let me see what you mean. Let’s start with revealed preference:

What do you propose doing about that? Keep in mind that I agree with Eliezer—my disagreement is with Knecht. So if your answer is to play Rationalist’s taboo against the word ‘choice’, then you’re not disagreeing with what I intended to say.

constant: buys, eats, etc. Here it’s not any more necessary to assert or imply deliberation (which is what I think you mean by saying “choice” is central for economic theory for the person than it is to assert it for an amoeba or for the direction a fire moves. It’s true many great scientists informally use “choice” to describe the actions of non-human, and apparently non-sentient phenomena, and I wouldn’t see the harm in doing so in an informal sense describing human actions if what I think is appropriate skepticism about conventionally intuitive models of “free will” and human experience of “choice” was maintained.

Sorry if this post isn’t more clear. I’m forced to jot it off rather quickly, but I wanted to attempt the timely answer you deserve.

Hopefully, you are not addressing an important distinction. You haven’t said what is to be done with it. The passage that I quoted includes these words:

The bundles of goods that are affordable are precisely the bundle of goods among which we choose.

Hopefully writes: constant: buys, eats, etc. Here it’s not any more necessary to assert or imply deliberation (which is what I think you mean by saying “choice”

No, it is not what I mean. A person chooses among actions A, B, and C, if he has the capacity to perform any of A, B, or C, and in fact performs (say) C. It does not matter whether he deliberates or not. The distinction between capacity and incapacity takes many forms; in the definition which I quoted the capacity/incapacity distinction takes the form of an affordability/unaffordability distinction.

Joseph Knecht, you call it a quibble, but it seems to me that it is the whole key to dissolving the question of free will and could-ness. If Eliezer really did subtly violate the Taboo in a way I didn’t notice, then what I have in my head is actually a mysterious answer to a mysterious question; I’m at a loss to reconcile my feeling of “question dissolved!” with your assertion that the Taboo was violated.

In case it’s not obvious, Rationalist’s Taboo lets you construct the Taboo concept out of elements that don’t themselves use the concept.

So if e.g. I must play Taboo against “number”, I can describe a system for taking pebbles in and out of buckets, and that doesn’t violate the Taboo. You’re the one who violates the Taboo if you insist on describing that system as a “number” when I just talked about a rule for putting a pebble in or taking a pebble out when a sheep leaves the fold or returns, and a test for an empty bucket.

Joseph Knecht says to Eliezer,

Congratulations to Joseph Knecht for finding a flaw in Eliezer’s exposition!

I would like his opinion about Eliezer’s explanation of how to fix the exposition. I do not see a flaw in the exposition if it is fixed as Eliezer explains. Does he?

To be clear, there are two different but related points that I’ve tried to make here in the last few posts.

Point 1 is a minor point about the Rationalist’s Taboo game:

With regard to this point, as I’ve stated already, the task was to give a reductive explanation of the concept of possibility by explaining it in terms of more fundamental concepts (i.e., concepts which have nothing to do with possibility or associated concepts, even implicitly). I think that Eliezer failed that by sneaking the concept of “possibile to be reached” (i.e., “reachable”) into his explanation (note that what we call that concept is irrelevant, reachable or fizzbin or whatever).

Point 2 is a related but slightly different point about whether state-space searching is a helpful way of thinking about possibility and whether it actually explains anything.

I think I should summarize what I think Eliezer’s thesis is first so that other people can correct me (Eliezer said he is “done explaining” anything to me, so perhaps others who think they understand him well would speak up if they understand his thesis differently).

Thesis: regarding some phenomenon as possible is nothing other than the inner perception a person experiences (and probably also the memory of such a perception in the past) after mentally running something like the search algorithm and determining that the phenomenon is reachable.

Is this substantially correct?