Killing Socrates

Or, On The Willful Destruction Of Gardens Of Collaborative Inquiry

One of the more interesting dynamics of the past eight-or-so years has been watching a bunch of the people who [taught me my values] and [served as my early role models] and [were presented to me as paragons of cultural virtue] going off the deep end.

Those people believed a bunch of stuff, and they injected a bunch of that stuff into me, in the early days of my life when I absorbed it uncritically, and as they’ve turned out to be wrong and misguided and confused in two or three dozen ways, I’ve found myself wondering what else they were wrong about.

One of the things that I absorbed via osmosis and never questioned (until recently) was the Hero Myth of Socrates, who boldly stood up against the tyrannical, dogmatic power structure and was unjustly murdered for it. I’ve spent most of my life knowing that Socrates obviously got a raw deal, just like I spent most of my life knowing that

It now seems quite plausible to me that Socrates was, in fact, correctly responded-to by the Athenians of his time, and that the mythologized version of his story I grew up with belongs in the same category as Washington’s cherry tree or Pocahontas’s enthusiastic embrace of the white settlers of Virginia.

The following borrows generously from, and is essentially an embellishment of, this comment by @Vaniver.

Imagine that you are an ancient Athenian, responsible for some important institution, and that you have a strong belief that the overall survival of your society is contingent on a reliable, common-knowledge buy-in of Athenian institutions generally, i.e. that your society cannot function unless its members believe that it does function.

This would not be a ridiculous belief! We have seen, in the modern era, how quickly things go south when faith in a bank (or in the financial system as a whole) evaporates. We know what happens when people stop believing that the police or the courts are on their side. Regimes (or entire nations) fall when their constituents stop propping up the myth of those regimes. Much of civilization is shared participation in self-fulfilling prophecies like “this little scrap of green paper holds value.”

And if you buy

“My society’s survival depends upon people’s faith in its institutions.”

...then it’s only a small step from there to something like:

“My society’s survival depends upon a status-allocation structure whereby [the people who pour their time and effort into building things larger than themselves] receive lots of credit and reward, and [the people who contribute little, and sit back idly criticizing] receive correspondingly less.”

People follow incentives, after all. If you want them to contribute, you need them to believe that there is something worth contributing to, and that they will benefit from doing so. If you fail to incentivize the hard work of creation and maintenance, or if you equally incentivize the much easier work of armchair quarterbacking, you will predictably see more and more people abandoning the former for the latter.

From this perspective, Socrates looks much less like a hero whose sharp wit punctured the inflated egos of various Athenian Ayn Rand villains, and much more like someone who found a clever exploit in the system, siphoning status without making a corresponding contribution.

By adopting a set of tactics wherein one can win any fight by only attacking and never defending, one can place immense burdens on any positive action (“Oh, so this is annoying? How would you define annoying?”) while not accepting any burdens of their own (“I’m just asking questions!”). One of Socrates’s innovations was a sort of shamelessness—if someone responded to him with “only a fool doesn’t understand what ‘annoying’ means!” he was happy to reply with “Indeed, I am a fool! So, can you explain it to me?”

This is not, in fact, a cooperative act. It is creating a burden—of explanation, of clarification, of interpretive and pedagogical labor—and then displacing that burden onto the other person. It’s increasing the cost of contributing to intellectual progress, and thereby discouraging people from trying to contribute.

It is indeed important and valuable to have one or two Socrati around, just as it’s important and valuable to have one or two court jesters who are willing to speak truth to power.

But Socrates—as affirmed by the majority vote of some 500 Athenians who convicted him—was corrupting the youth, i.e. setting an example which many of Athens’ young people were emulating.

If it looks like a substantial fraction of an entire generation wants to grow up to be jesters instead of kings or knights or counsellors, then the bedrock upon which the polis rests—the collective self-fulfilling prophecy—crumbles. A thousand hole-pokers will rapidly tear the social fabric to shreds. This is an existential threat, to which the Athenians (plausibly) responded proportionately!

It’s worth noting at least three other relevant things:

The preceding decade had contained a military defeat, a puppet government installed by the conquerors, a coup, a counter-coup, and a counter-counter coup; things in Athens were actually unstable, and it’s not difficult to be sympathetic to the view that this was the wrong time to be picking nits.

During the trial itself, Socrates remained committed to the bit, wielding the same weaponized disingenuousness that brought him there in the first place.

While the legend I absorbed in childhood holds that he was “murdered for telling the truth,” most accounts show that he was allowed to propose his own punishment, and suggested that the state “punish” him by providing him with free food and housing as payment for noble service rendered. When the state replied with “how about death, instead?” Socrates basically responded “if you kill me, all those youth I’ve corrupted are gonna keep on doing exactly the same thing I taught them to do,” which, again, sounds very hero-spitting-in-the-villain’s-eye if you’ve predecided that you know who the good guys are, and less so if you have not.

More directly quoting the comment from which the above descends:

A few years ago, it seemed to me like one of the big problems with LessWrong was that the generativity and selectivity were unbalanced. There wasn’t much new material posted on LW, and various commenters said “well, the thing we should do is be even harsher to authors, so that they produce better stuff!”, and when I went around asking the authors what it would take for them to write more on LW, they said “well, putting up with harsh comments is a huge drawback to posting on LW, so I don’t.”

Now, it would have been one thing if it were the top writers criticizing things—if, say, Eliezer or Scott or whoever had said “actually, I don’t really want my posts to be seen next to low-quality posts by <authors>” or had been skewering the flaws in those posts/comments. [Indeed, many great Sequences posts begin by quoting a reaction in the comments to a previous post and then dissecting why the reaction is wrong.] But instead, the commenter most frequently complained about by the former authors was a person who did not themselves write posts. [emphasis added]

Now, the specific person I had been thinking of had been around for a long time. In fact, when they first started posting, their comments reminded me of my comments from a few years earlier, and so I marked them as someone to watch. But whereas I acculturated to LW (and I remember uprooting a few deep habits to do so!), I didn’t see it happen with them, and then realized that when I had been around, there had been lots of old LWers to acculturate to, whereas now the ‘typical comment’ was this sort of criticism, instead of the old LW spirit.

“Oh,” I said in a flash of insight. “This is why they executed Socrates.”

If a culture has zero Socrati, then you end up with an emperor strutting naked through the streets, claiming to be wearing robes of the most diaphanous silk.

One Socrates can prevent that. One Socrates can, in fact, call it like it is, and poke holes in things that aren’t sound and defensible, and generally improve the health of the system via a kind of hormetic stress.

But if Socrates sets the vibe—if the youth of Athens decide that the right mode to be in is aggressively critical—if they view this as a noble calling, part of holding everyone else to account—if the percentage of people doing the Socrates thing rises above a pretty small threshold—

There’s only so much withering critique a given builder is interested in receiving (frequently from those who do not themselves even build!) before eventually they will either stop building entirely, or leave to go somewhere where buildery is appreciated, rewarded, and (importantly) defended.

(Someplace where the Socrati do not have concentration of force.)

It’s a dynamic tightly analogous to the Copenhagen Interpretation of Ethics, in which trying at all to help with a problem exposes you to blame and criticism, whereas turning a blind eye leaves you safely among the anonymous and un-attacked masses.

If trying to share any thoughts at all results in a metric ton of critique, criticism, nitpicking, sealioning, and unpredictable demands for rigor—

(Which, if left unanswered, tend to be treated by the Socratic crowd as moderately strong evidence that you were full of shit to begin with, ignoring alternative hypotheses like “maybe that question wasn’t worth the time and effort it would take to deconfuse the asker.”)

—then you will observe what we do, in fact, observe: multiple specific brilliant and talented writers who seem to be “just the type we want on LessWrong” who are oddly unwilling to come anywhere near the site.

(Some of them unwilling to come anywhere near the site anymore, despite the fact that they used to enjoy being here, back when the comment sections were primarily builders offering critique to each other, in an atmosphere of collaboration rather than one of evaluation and judgment.)

Vaniver continues:

There’s a claim I saw and wished I had saved the citation of, where a university professor teaching an ethics class or w/e gets their students to design policies that achieve ends, and finds that the students (especially more ‘woke’ ones) have very sharp critical instincts, can see all of the ways in which policies are unfair or problematic or so on, and then are very reluctant to design policies themselves, and are missing the skills to do anything that they can’t poke holes in (or, indeed, missing the acceptance that sometimes tradeoffs require accepting that the plan will have problems). In creative fields, this is sometimes called the Taste Gap, where doing well is hard in part because you can recognize good work before you can do it, and so the experience of making art is the experience of repeatedly producing disappointing work.

In order to get the anagogic ascent, you need both the criticism of Socrates and the courage to keep on producing disappointing work (and thus a system that rewards those in balanced ways).

Or, to put it another way:

There are a lot of LessWrong commenters who respond to perceived falsehoods with what looks a lot like an elevated sense of threat. “Don’t let that one through! That one’s wrong!”

But many of the actual claims being responded to in this fashion are not powerful snippets of propaganda, or nascent hypnotic suggestions, or psychological Trojan horses. They aren’t the workings of an antagonist. They’re just half-baked ideas, and you can either respond to a half-baked idea by helping to bake it properly...

...or you can shriek “food poisoning!” and throw it in the trash and shout out to everyone else that they need to watch out, someone’s trying to poison everybody.

(Or pointedly interrogate the author on why exactly they chose to bake their idea this way when it’s so clearly inadequate, would you please explain what made you think that this dough was sufficiently risen to be worth serving?)

It’s the difference between, say, writing a 3300-word piece about how one section of someone else’s building is WRONG, and spending 3300 words suggesting a replacement that might solve the perceived problem better, without containing Flaw X or causing Negative Side Effect Y.

The end result of Socrates Unchecked is not, in fact, a bastion of pure reason and untainted truth. That’s a fabricated option, like believing that a ban on price gouging during a disaster will result in the normal amount of gasoline being available at the normal prices.

What happens instead, in practice, is evaporative cooling, as the most sensitive or least-bought-in of [the authors/builders who made your subculture worth participating in in the first place] give up and go elsewhere, marginally increasing the ratio of critics to makers, which makes things marginally less rewarding, which sends the next bunch of builders packing, which worsens the problem further. A steady influx of, say, people worried about AI can slow this process, but not stop or reverse it (especially if the newcomers pick up on the extant vibe and conclude that That’s How We Do Things Around Here).

People like to repeat the phrase “well-kept gardens die by pacifism,” but they also flinch from killing Socrates, when Socrates is busy suffocating every seedling he can find, and draining the joy out of the act of gardening.

I claim this is an error.

- We’re losing creators due to our nitpicking culture by (EA Forum; 17 Apr 2023 17:24 UTC; 167 points)

- Moderation notes re: recent Said/Duncan threads by (14 Apr 2023 18:06 UTC; 50 points)

- 's comment on Moderation notes re: recent Said/Duncan threads by (23 Apr 2023 23:41 UTC; 37 points)

- Summaries of top forum posts (17th − 23rd April 2023) by (EA Forum; 24 Apr 2023 4:13 UTC; 26 points)

- 's comment on Moderation notes re: recent Said/Duncan threads by (23 Apr 2023 23:57 UTC; 26 points)

- 's comment on Moderation notes re: recent Said/Duncan threads by (14 Apr 2023 19:38 UTC; 23 points)

- Summaries of top forum posts (17th − 23rd April 2023) by (24 Apr 2023 4:13 UTC; 18 points)

- 's comment on Moderation notes re: recent Said/Duncan threads by (15 Apr 2023 16:34 UTC; 15 points)

- 's comment on LW Team is adjusting moderation policy by (12 Apr 2023 0:31 UTC; 12 points)

- 's comment on On “aiming for convergence on truth” by (12 Apr 2023 7:09 UTC; 11 points)

- The LW crossroads of purpose by (27 Apr 2023 19:53 UTC; 11 points)

- 's comment on Moderation notes re: recent Said/Duncan threads by (15 Apr 2023 17:11 UTC; 8 points)

- 's comment on If Clarity Seems Like Death to Them by (5 Jan 2024 18:19 UTC; 3 points)

>> “There’s only so much withering critique a given builder is interested in receiving (frequently from those who do not themselves even build!) before eventually they will either stop building entirely, or leave to go somewhere where buildery is appreciated, rewarded, and (importantly) defended.”

Perfect summary of my experience co-founding and directing a summer program affiliated with the rationality community (the summer program is ongoing to this day). I quit and left after two years. For a long time, I thought building summer programs inevitably meant a bunch of armchair critics.

Then I built another summer program with people who’ve never heard of rationality, and they actually respected my work rather than belittling it! People helped me build the program rather than casting stones from the sidelines! I’ve never worked for the rationality community again.

One summer program had a ton of issues that pop up on Twitter, that my non-rationalist friends ask me about and I still have to answer for—even though I haven’t been involved for 5 years. The other program gives me nothing but good press. I’ll let you guess which is which

(First time posting on LW, and this is an inevitably simplified story. I was far from a perfect camp founder or director. But that was also the case for the non-rationalist summer program! and somehow one experience was significantly more constructive and empowering.)

1) I agree with the spirit of this. To re-quote my comment on Elizabeth’s Butterfly Ideas post:

2) That said, I really don’t like the Socrates analogy here. The loose analogy between execution and moderation seems entirely unnecessary, and sounds like a call for violence. I think that makes the discussion about moderation more emotionally charged, and I don’t see how that helps anyone.

Furthermore, Wikipedia is unclear to which extent Socrates’ execution was for political vs. religious reasons. Insofar as it was for religious reasons, that would make him the victim of a religious dispute, or even a martyr; I think this interpretation works against your thesis.

3) Finally, I would like to suggest a norm whereby, if you criticize specific active LW users, to mention that they’re banned from commenting on your posts. (I guess you could alternatively mention that in your commenting guidelines.) And that’s coming from someone who has seen some of the exchanges these users are involved in, and so very much understands why they’re banned.

The book “Pharmakon” by Michael Rinella goes into some detail as to the scarcely-known details behind the “impiety” charge against Socrates. If I recall correctly from the book, it was not just that Socrates rhetorically disavowed belief in the gods. The final straw that broke the camel’s back was when Socrates and his disciples engaged in a “symposion” one night, basically an aristocratic cocktail party where they would drink “mixed wine” (wine sometimes infused with other substances like opium or other psychoactive herbs) and then perform poetry/discuss philosophy/discuss politics/etc., and then afterwards a not-infrequent coda to such “symposions” would be a “komos” or drunken parade of revelry of the symposion-goers through the public streets of Athens late at night. Allegedly, during one of these late-night “komos” episodes, Socrates and his followers committed a terrible “hubris,” which was to break off all of the phalloi of the Hermes statues in the city, which was simultaneously juvenile and obnoxious and a terrible sacrilege.

Fascinating! Though that once again gives the charge of “corrupting the youth” a different connotation than the one assumed in Duncan’s post.

Right now it feels like it’s an either/or choice between criticism and construction, which puts them in direct opposition, but I don’t think they’re necessarily in conflict with each other.

After all, criticism that acknowledges the constraints and nuances of the context is more meaningful than criticism that is shallow and superficial, and criticism that highlights a new perspective or suggests a better alternative is more useful than criticism that only points out flaws. In a sense, it’s not that there’s too much criticism and not enough of contributions, it’s that we want critiques that are of higher standards.

Maybe instead of trying to figure out how to determine the right amounts of criticism individuals are exposed to, we can instead focus on building a culture that values and teaches writing of good critique? There would still (and always be) simplistic or nitpicky criticisms, but perhaps if the community were better at identifying them as such, and providing feedback on how to make such comments better, things would improve over time.

Admittedly, I don’t really know what this would look like in practice, or whether or not it would make a difference to the experience of authors, but putting the issue in terms of killing Socrates feels like dooming it to win/lose or lose/lose solutions...

I don’t see any group of people on LW running around criticizing every new idea. Most criticism on LW is civil, and most of it is helpful at least in part. And the small proportion that isn’t helpful at all, is still useful to me as a test: can I stop myself from overreacting to it?

Civility >>> incivility, but it is insufficient to make criticism useful and net positive.

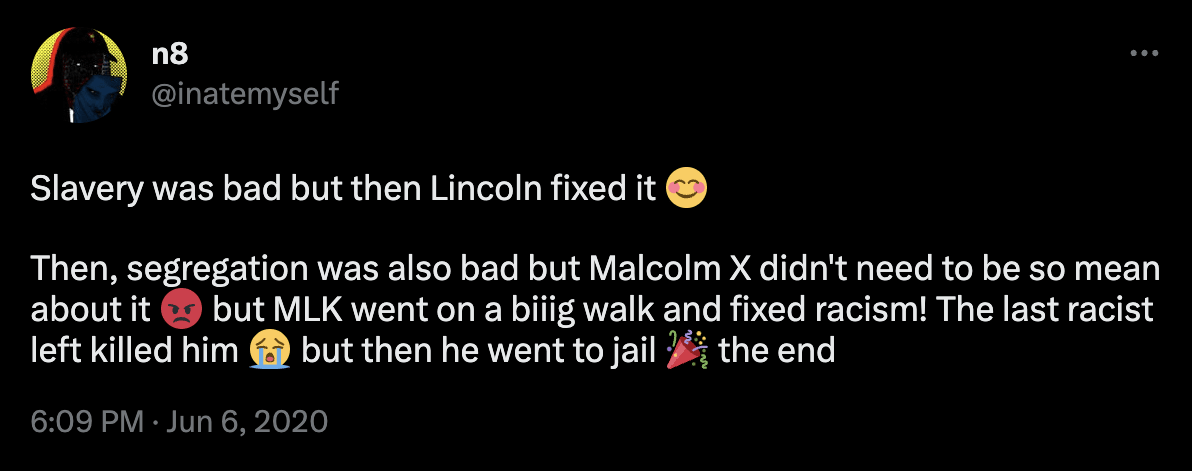

There is a LOT wrong with the below; please no one mistake this for unnuanced endorsement of the comic or its message; I’m willing to be more specific on request about which parts I think are good versus which are bad or reinforcing various confusions. But I find this is useful for gesturing in the direction of a dynamic that feels very familiar on LW:

https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/9weLK2AJ9JEt2Tt8f/politics-is-the-mind-killer

You shouldn’t have posted this even if you agree with what it’s actually saying, let alone if you don’t.

And if you just don’t know what it’s actually saying, you really shouldn’t have posted it.

I intended to indicate “I do not agree with 100% of this comic’s content, nor with 100% of reasonable interpretations of its message.”

I did not intend to communicate “I disagree with 100% of this comic’s content, or with 100% of reasonable interpretations of its message.”

I posted it here correctly: to give a gesture in the direction of a particular problem/dynamic; it does in fact concisely and evocatively succeed at doing so.

You could say the same thing for the Nixon example. That doesn’t justify using politically charged examples.

I deny that the burden of proof is where you claim it is. *shrug

(This is part of a larger issue where someone will be like “Heuristic X!” and other people, later, will act as though merely quoting the person who asserted Heuristic X is sufficient to demonstrate that Heuristic X is both correct-in-general and applicable-in-this-instance. Merely quoting that snippet does not, in fact, win you the argument!)

The Nixon example is politically charged by content. The sea lion comic only by context. If one doesn’t know that specific detail of history of the internet, it’s pretty neutral.

Out of curiosity, what is it “actually” saying? The comic strip has a whole wikipedia article, in which I did not find a politically charged meaning mentioned (obviously given the context I had to make an effort to get their without asking!).

It’s claiming that Gamergate supporters who don’t want to be called sexist, and who politely object to being called sexist, are behaving like the sealion in the strip.

But the strip itself uses a completely made up concept (of talking Sea Lions). I agree that very often that concept is used in bad faith (no matter how you put it, random outbursts on Twitter are not like talking in the privacy of your home, and you have no right to complain that random strangers are engaging you if you’re literally on the Engage Random Strangers Platform), but while the comic was written for a certain context, on its own it’s perfectly abstract. It’s just gesturing in the direction of what we could call a form of unproductive nagging. You can use obstructionism tactics in debates, like simply trying to annoy the other person to the point that they concede your point just to be left alone.

Looking at the strip itself, it’s pretty weird. The sea lion’s words are polite, but being in someone’s house uninvited is a violation of their property rights. How did he even get in—breaking and entering? Meanwhile, the person’s reaction is not to say “oh my god, how did he get in?” or “get out of here or I will call the police”, but to be unsurprised and annoyed.

In other panels where they’re having tea or breakfast, it’s unclear whether it’s in their house—in which case the same stuff as above applies—or in some third-party restaurant place, in which case they would at least have the recourse of complaining to the owner and trying to persuade him that this sea lion is bothering his patrons and driving away business. Even in public, if such behavior were persistent enough, I imagine it could rise to the level of “stalking” and be punishable by law; though this is probably a grey area, and let’s assume the sea lion is doing his best to remain technically within the law.

The strip could have had the sea lion follow them around while they’re outside in public, and maybe had them sigh in relief when they close the door to their house. It could have shown them arguing with an unsympathetic proprietor about his behavior. But no, they’re not even looking for any recourse against him. Instead, it showed the sea lion following them inside, everywhere, into their bedroom while they’re trying to sleep, and this is presented as just a fact of life. Why?

I won’t assume the worst motives—it’s possible that the author made the situation more extreme for absurdity and humor—but whatever the intent, clearly “he follows you into your bedroom when you’re trying to sleep” would intensely strengthen the elements of annoyance and of “oh god I can’t escape him” for a real person. If all the scenes with the sea lion were in public, the emotional point wouldn’t land as heavily… for those who don’t think about the assumptions. (The fact that it’s a talking sea lion generally encourages suspension of disbelief. It’s also a key part of the comic: a man following a woman into her bedroom uninvited would be interpreted very differently.)

The strip embodies an acute lack of distinction between “criminal trespass and stalking” and “annoying but maybe-permissible public behavior”. Blurring these together seems to be a key part of how it gives emotional weight to its point, which perhaps made it resonate with many more people than it otherwise would have.

The strip embodies the exact mindset that leads to “complaining that random strangers are engaging you when you’re literally on the Engage Random Strangers Platform”. I don’t think there’s a way it could make sense outside the context of social media platforms like that; the specific thing of “communications from randos appearing in your bedroom at night, and this being unsurprising” perfectly fits internet tech and not much else. (Getting phone calls all night would be similar, and actually worse if it prevented you sleeping, but you could unplug the phone—which is kind of the issue in a nutshell. I suspect the type of person with this mindset has their phone set to give audible notifications on all kinds of social media messages, keeps their phone nearby, and might not even set it to do-not-disturb mode at night.) The same applies to how the sea lion magically overhears the conversation and appears from nowhere in the first place, and no one is surprised at this, nor at how he keeps magically appearing in all subsequent places.

You could look at the strip and say “the point is that the sea lions are annoying, persistent, and their words are polite, and you’re supposed to abstract away everything else”. I think that would be wrong; I think that would mean abstracting away most of the logic (and the appeal) of the comic, and, among other things, when choosing a name for bad behavior I want far better epistemics than that.

I submit that “the point is that the people complaining about the sea lions have an immature attitude towards social media, plus they see nothing wrong with disparaging groups of people in public and are mad when called on it, and generally they are massive hypocrites”. (I know it’s not what they intend to say, but it is the meaning I take from their speech.) That being the case, it makes me uneasy when I see someone I respect use the term from the comic unironically.

Yeah, honestly that’s my take from it as well. But I think it’s true that in certain settings you can use the “polite questions” approach as obstructionism, and it might work. For example, any kind of work meeting, an assembly, a council of any sort. “Asking polite questions” as a sort of DDoS attack on the bandwidth of any discussion is a possible dirty tactic that gives you plausible deniability. However knowing the context, the actual complaint here is probably: “I made a sweeping statement on social media about people, who should not be offended by because obviously I wasn’t talking about all of them, just the bad ones, they know who they are, and then those people kept nagging me on the internet which then compelled me to answer and read their answers”. To which the sane answer is “then don’t make stupid sweeping statements on social media about people, or if you do and then are nagged for it, shut down your goddamn phone”. So I think the concept itself of sealioning isn’t completely out there, but the specific meaning the strip was originated from is actually a pretty self-centred perspective.

I see it as a case of a potentially useful term that just happened to be used badly on its very first occurrence.

If you take it in the abstract, it’s bad for a somewhat different but also somewhat related reason: If you’re prejudiced against X, X is justified in objecting under almost any circumstance that isn’t actually barging into your home.

If you go out in public proclaiming about how you just can’t stand Jews, any “unproductive nagging” you get from Jews is your own fault.

True enough, though that depends a lot on what the category is. Generally speaking, immutable characteristics are a no-go, but if I say “I hate fascists”, that’s not due to some general quality, that’s due to the specific choice of believing in fascism, which makes whoever considers themselves a fascist guilty, by definition, of possessing exactly the traits that I consider hateable. Still, I would say that insofar as I bring that up in a public forum, I should expect some pushback, and will in turn respond by explaining why and how precisely I think fascists are worthy of hate.

That said, really, I do think this is mostly a mix up between private/public spheres. Some people go on Twitter and generally treat it as if they were chatting only with close friends, then (either in good or bad faith) act outraged and surprised when random people eventually see their posts in their feed and answer them. But the whole thing is designed specifically to try to elicit those interactions: show provocative statements to people who will be provoked, because that maximises engagement. If you don’t understand that much you just shouldn’t be on Twitter (I’m not sure if I should, more in a general “holding onto your sanity” sense, and I understand it pretty well).

Thank you.

hi, I do that! I try to do it nicely, because I do it on purpose with an aim to help people feel challenged but welcome. I’m happy to also make a habit of criticizing bad criticism :D criticize me criticizing!

Before reading this post, I usually would refrain from posting/commenting on LW posts partially because of the high threshold of quality for contribution (which is where I agree with you in a certain sense), and partially because it seemed more polite to ignore posts I found flaws in, or disagreed with strongly, than to engage (which costs both effort and potential reputation). Now, I believe I shall try to be more Socratic—more willing to as politely as I can point out confusions and potential issues in posts/comments I have read and found wanting, if it seems useful to readers.

I find Said’s critiquing comments (here are three good examples) extremely valuable, because they serve as a “red team” and a pruning function for the claims the post author puts forth and the reasoning behind them. What you seem to consider as a drive-by criticism (which is what I believe you think Said does) that puts forth a non-trivial cost upon you, is cost that I claim you should take upon yourself because your writing isn’t high quality enough and not “pruned” enough given the length of your posts.

That is the biggest issue I have with your writings (and that of Zack too, because he makes the same mistake): you write too much to communicate too little bits of usefulness. This is how I feel for all your 2023 posts that I have read (or skimmed, rather) -- it points to something useful, or interesting, but it is absolutely not worth the time investment of reading such huge and long-winding essays. I don’t even think you need to write them that long to provide the context you believe necessary to convey your points.

The good thing is that with comments like those of johnswentworth, Charlie Steiner, and FeepingCreature all give people like me the context they need to interpret how useful your post is, without having to read the post itself. Notice that all these comments are short and succinct while also being very relevant to the post, without nitpicking. This is the sort of writing I respect on LW. It is not coincidental that two of these three people are full time alignment researchers.

Right now, I can simply ignore your posts until they get sufficient traction (which is very easy given how popular you are) that the comments give me an idea of the core of your post and what the most serious weaknesses of your argument are, and with that I have gotten the value I need (given I skim your post while doing so, whenever relevant). However, your desire to censor Said’s comments gets in the way of this natural filter. Said’s comments provide incredible value to both you and your audience, even if you do not interact with them! To you, it provides you valuable evidence you can weigh up or down given how valuable you find Said’s comments in general, and to LW audience, it provides a way of knowing the critical weaknesses of your argument without having to read your post and parse it and try to figure out the weaknesses in it.

You claim emotional damage to yourself and to other people due to drive-by critiquing comments, and that this leads to an evaporative cooling effect where people post lesser and lesser. This seems like a problem, but given one person spending half an hour pruning their writing to improve its quality, and a hundred readers spending between ten minutes to an hour processing and individually critiquing the writing to calibrate and update their world model, I would want the writer to eat the cost. That is what I personally choose, after all. And by extension, I have realized that me critiquing other people’s contributions is also incredibly valuable, and I will start to do that more. And anyway, this probably isn’t a trade-off, and there may be solutions that do not impose a cost on either party.

As far as I know, Said seems to believe that moderation of comments should not be left to post authors because this creates a conflict of interest. Its consequences are simple: I get less value out of your posts and by extension, LW. Raemon’s decision to create an archipelago-like ecosystem makes sense to me given his goals and assumptions laid out in the post, but you seem to want more aggressive action against people whose criticisms you dislike.

“You don’t much care if This Rando doesn’t get it”, and I would be fine with that if you weren’t taking actions that have clear externalities for readers like me by making Said’s critiquing comments and comments of a similar nature by other people less welcome on LessWrong—both as a social norm and at the moderator level.

Pulling up a thought from another subthread:

Basically, I’m claiming that there are competing access needs, here, such as can be found in a classroom in which some students need things to be still and silent, and other students need to fidget and stim.

The Socrati and the Athenians are not entirely in a zero-sum game, but their dynamic has nonzero zero-sum nature. The thing that Socrates needs is inimical to the thing the Athenians need, and vice versa.

I think that’s just … visibly, straightforwardly true, here on LW; you can actually just see how, as the culture has shifted Socratesward, many authors have left.

Other authors have arrived! Socrates had many followers! There were a lot of people who liked his whole deal, and were enjoying the vibe!

But I’m claiming that the current tradeoff leans in the direction of “make things optimal for mesaoptimizer and suboptimal for Duncan_Sabien,” and separately that “things being optimal for mesaoptimizer actually makes LessWrong as a whole more likely to dry up and shut down, since LW depends on people being willing to write essays.”

(The Socrati mode being better for commenters than authors, and the Athenian mode being better for authors than for (some) commenters (such as mesaoptimizer).)

This response has completely sidestepped the crucial piece, which is to what extent [that kind of commentary] drives authors away entirely.

You’re acting as if you always have fodder for that sort of engagement, and you in fact don’t; enough jesters, and there are no kings left to critique.

Given what Zack writes about, I think he has no choice but to write this way. If he was brief, there would be politically-motivated misreadings of his posts. His only option is to write a long post which preemptively rules those out.

(Sorry for triple reply, trying to keep threads separate such that each can be responded to individually.)

I claim that the LW of 2023 is worse at correctly identifying the most serious weaknesses of a given argument than the LW of 2018.

Relative to the LW of 2018, I have the subjective sense that there’s much much more strawmanning and zeroing-in-on-non-cruxes and eliding the distinctions between “A somewhat implies B,” “A strongly implies B,” and “A is tantamount to B.”

I would genuinely expect that a hypothetical LWer who gets the gist of my arguments mostly from comments written in disagreement is, in fact, getting the gist of a cardboard cutout created by people who (say) don’t actually read the thing that I wrote, but instead spend a few minutes on the first paragraph and then leap to reply “this is insane.”

(That user has since apologized for that specific thing that they did, and I wouldn’t harp on it except that I think it’s genuinely representative of, and emblematic of, the thing that LW is more of now than it used to be five years ago. The recent response to my Basics post, for instance, contained loads and loads of stuff that I straightforwardly agree with, presented as if it was contra my claims, and it simply wasn’t.)

A user who waits to read the top couple of disagreeing comments is a user who’s gonna very quickly build a shoulder strawman without even noticing that that’s what they’re doing.

FYI I think I disagree with the 2018 vs 2023 claim here, I think everything you’re pointing at was in fact worse in 2018 (i.e. there were more users actively pushing for it, and most of them kinda left since then)

I would trust you to have a better sense of the overall LW experience, so this is evidence that this might be a my-posts problem, but it’s definitely gotten worse for me specifically. It was not this hard to get people to let go of their strawmen even with stuff like Punch Bug (which is a topic people have very strong preconceptions and feelings about).

Huh. I am surprised about that.

From another comment on this post:

A specific thing people could do that I think would tremendously help the site culture, without at all limiting our ability to be critical when warranted, is just to preface critical comments with evidence that the critic has put in some work to ensure they’re understanding the original material.

Ideally, that would entail providing:

A quote of the statement they disagree with

A brief description of the context of the post and how the bit they’re criticizing relates

At least some engagement with the specific supporting arguments or evidence originally provided.

Engaging with the supporting arguments and evidence is essential.

This is a form of debate I think is productive because it engages the arguments and evidence offered by the other person:

“I think A because B”

“I think not-A because I think not-B because C,” or “I think not-A because I think C, which outweights B because D.”

This is a form of debate I think is unproductive because the second person doesn’t engage with the first person’s reasoning—only with their claim:

“I think A because B”

“I think not-A because C” (which doesn’t explain C’s relationship with B), or “I think not-A because I think C, which outweighs B” (which doesn’t explain why C outweighs B”.

In general, I think it’s up to each respondant to show engagement with the previous person. There’s a certain privilege of the prior speaker: if I say “A because B,” and you want to voice your disagreement, then you have to at least say “not-A because not-B because C.” You don’t just get to say “not-A because not-B.” That might be a little unfair, but it also gives me the onus to then say “I still think A because C, which outweighs B, because D.”

I think that a definitive feature of crappy Socratic interrogations of the kind Duncan’s describing here is the absence of this feature, and the presence of this feature defines the best conversations I’ve had in any environment.

First, ironically I guess, an incidental nitpick: the plural of “Socrates” is not”Socrati”. (I don’t think there’s any case to be made for anything other than “Socrateses”.)

More substantively: I think the following are both true: (1) excessive, hostile and/or unconstructive criticism is harmful; (2) one of the things that makes LW an interesting place to discuss things is a more-than-averagely critical culture, where (at least to some extent, at least in principle) we are trying to get things right and if something seems wrong then helping it become Less Wrong can matter more than maintaining a polite welcoming atmosphere.

There are a couple of LW regulars whom Duncan finds particularly annoying on the grounds that they are too Socratic, criticizing more than they build, criticizing unimportant details, etc. I understand why Duncan finds them annoying; I too find them annoying sometimes; but I do not think LW would be improved by “killing” them. It may be that they would be more useful to the community if they adopted a different balance of criticism to construction. But we don’t actually have the option of choosing between “X” and “X, but more construction and less criticism”: they are who they are, they have the particular abilities and inclinations that they have, and if what they do is mostly criticize, well, I think that criticism is valuable on net even if it’s annoying.

And I’m not sure what they do is mostly criticize. One of those repeated adversaries is one of the creators and maintainers of GreaterWrong, which I believe many people have found valuable as a different UI on top of the LW backend; that seems pretty constructive to me. And the other has put a lot of time and trouble into thinking about, and promoting, a particular view of how language ought to be used, which seems to me clearly a constructive enterprise even though as it happens (a) I disagree with that view and (b) I think it is to an uncomfortable extent a consequence of that person’s views on a particular hot-button socioculturopolitical issue. For that matter, Socrates (or more precisely Socrates-as-portrayed-by-Plato) seems to have had a bunch of positive ideas he was pushing, which were interesting whether or not correct, and wasn’t just a nitpicker, even if what got him executed was his nitpickery.

Also, consider the “3300-word piece about how one section of someone else’s building is WRONG”. That’s not such a bad description of it… except that I think said piece does in fact suggest what its author thinks would be better than that section of the building. It doesn’t suggest how to “solve the perceived problem better” because (as I understand it) its author doesn’t agree that the perceived problem is a real problem. Zack’s piece is not unconstructive nitpickery, as I see it; it’s a genuine disagreement about what constructive truth-seeking discourse looks like. (I agree with Duncan more than I do with Zack about what constructive truth-seeking discourse looks like. But my complaint is that Zack is wrong, not that he’s not trying to be constructive.)

Now, for sure I could be wrong about the overall value of criticism on LW. Maybe it does more harm by driving away good posters than it does good by helping people refine their ideas and discouraging unnecessary sloppiness. We should absolutely be aware of that danger. But before taking a step as drastic as “killing Socrates” I think we would want to be pretty confident that the harm Socrates does outweighs the good. I think it’s very far from clear that that was true of Literal Socrates, and I think it’s very far from clear that it’s true of Duncan’s adversaries.

Dude, why?

I think it was meant in good humor, but it did feel a little on the nose.

And following up on this, “Socrateses” is probably wrong. 😅

In Modern Greek, the plural would be Socratides (Σωκράτηδες; the primary stress is on a) or Socrates (Σωκράτες; way less commonly used). With a 2-min search I found this ref to make the case for Socratides.

[And since I happen to have an Ancient Greek language teacher in the next room, by asking her, she gave the following reference]

In Ancient Greek, it would be Σωκράται. If you look at section “133. α” here you can find its conjugation in the example. This would be translated to either: Socrate, or most probably Socratai (again with the primary stress on “a” and with the last “ai” pronounced as the “ai” in “air”.

Given the above, the term originally used by Duncan (Socrati), is pretty damn accurate.

Huh, interesting. I still think “Socrateses” is preferable in English—generally foreign imports into English don’t pluralize according to source-language patterns other than the best-known ones; e.g., if someone writes “octopodes” you can be pretty sure they are doing it for humour, and if someone writes “censūs” you can be pretty sure you’ve somehow dropped into an alternate universe.

Still, I hadn’t realised that there was any standard Greek plural for “Socrates” (it’s not obvious that proper nouns necessarily have plural forms, after all) and in particular hadn’t realised that “Socratai” would be the canonical thing.

I don’t think I agree that “Socrati” is a good anglicization of “Σωκράται” if you are going to use a Greek plural, though. Is there any other case where a Greek plural ending -ai turns into an English version in -i?

IIRC from the one relevant course I took over 15 years ago, that’s largely a difference between early Plato, reporting what Socrates did and said, and later Plato, using Socrates as a character/mouthpiece for his own ideas.

(To clarify—is your recollection that “Plato’s early Socrates, more closely reflecting actual Socrates, was a nitpicker; and Plato’s late Socrates, a mouthpiece for Plato, was pushing for stuff”? Or the other way around?)

According to the SEP page about Plato, the former is a widely held view (but the author of that page thinks it’s an oversimplification).

This. Awesome reference, thanks!

And I’m sure it is an oversimplification! Obviously Socrates was human and knew things and had ideas, no matter what he says and does in some of the dialogs. And obviously Plato was human and didn’t wait until late in his career to start having ideas of his own. And I never did ask how any classicists and historians decided what order Plato wrote his dialogs in, or whether it was controversial.

I think if LW’s stance is “we’re going to let this person drive away high-quality writers on the regular because we like the fact that they made GreaterWrong,” that’s worth being explicit about.

(That person is more responsible than any other single individual for Eliezer not being around much these days.)

To be clear, I wasn’t at all saying that. I was saying “this person is clearly not interested only in destructive nitpicking; here’s a substantial high-effort constructive thing they have done”.

Whether their presence on LW is net positive or negative is a completely separate question. (My current opinion is “clear net positive” but of course I could be wrong, and if e.g. it were the case that we could have Said or Eliezer but not both then that would be an argument on the other side—though I really don’t like the idea of banning user A because user B dislikes having them around even if user B is someone we would very much like to be here.)

I agree it’s a high-effort, constructive contribution.

I don’t know how to contrast it with making the business of actually writing LW content far worse than it otherwise would be.

I agree it’s a bad idea to ban user A because user B dislikes having them around. I think it’s a good idea to ban user A because users B, C, D, G, L, P, Q, R, and W, all of whom were valued contributors, all cited user A on their way out the door.

Have those people in fact said “I am leaving LW because I dislike interacting with Said”? Or is it something more like “I am leaving LW because I dislike the over-critical culture, of which Said is the clearest example”? Because if it’s the latter then it could be simultaneously true that (1) lots of people abandoning LW gave Said’s interaction style as a reason for leaving and that (2) banning Said wouldn’t actually do much to help.

(I remark that I have no evidence other than your say-so that lots of people have cited Said in explaining why they left LW, and that people’s explanations of such things are not always an accurate reflection of the actual causes. I am not, for the avoidance of doubt, claiming or even conjecturing that either you or they are/were lying.)

Since we’re talking about it, I have also told the mods that Said is one of three people who are readily top of mind at having a net negative impact on my LW experience. I’d just sort of been dealing with it, and personally I do not favor banning people sitewide for making me feel uncomfortable. But one of the mods reached out to me and specifically asked about factors influencing my experience of LessWrong, and the vibe and some of the specific commenters Duncan’s pointing out here are what I had reported was the main negative factor for me.

One of the facets of your comment here is that it puts the emphasis in a frustrating place: instead of saying “ah, n of 1, it’s good to know Said bugs you, I wonder if anybody else feels the same way,” it says “you’re the only person I’ve ever heard of complaining about Said, although I’m not saying you’re lying,” which is like a super negative way of being “neutral” about what Duncan said.

Like, imagine you said that to your significant other if they told you that one of your mutual friends, Bob, bothered your SO a lot during conversations, and that your SO had heard from other friends that Bob was very bothersome as well and made them not want to come and hang out. Would you say something like “I remark that I have no evidence other than your say-so that lots of our mutual friends have cited Bob in explaining why they don’t come to our board game night...?”

That sort of approach is a great way to alienate people and kill relationships. Why not just come right out and say “I don’t trust you enough to update ~at all on your reports about how other people feel about Bob?” That would at least be honest!

Did you know about the option to ban people from your posts? If yes, may I ask why you didn’t ban Said?

I didn’t know about that until I saw somebody mention it in another comment today. I will probably start doing this.

I did not intend to say or imply “you’re the only person I’ve ever heard of”, nor to be super-negative, and I don’t think I trust Duncan particularly less (or more) than a typical other prominent LW participant. (But I might trust him less specifically when reporting negative things about Said than I would trust him on other matters, and I would likewise trust Said less specifically when reporting negative things about Duncan.)

If anything I said caused anyone else to trust Duncan less, or caused Duncan any distress, then that was very much not an intended effect and I apologize.

I do, rereading what I wrote, see how it could be interpreted as having a much stronger negative subtext than I intended. What I intended was along the following lines: What Duncan is saying in this thread about “more than a dozen” high-quality ex-LWers citing Said as a major reason for their departure is, unlike the already well-known fact that Duncan himself finds Said intensely unpleasant to interact with, new information for me; but I am aware that when people find one another intensely unpleasant to interact with the things they say about one another are not always perfectly accurate, even when everyone involved is aiming to be truthful and fair, and I want to be cautious in how much I adjust my estimate of Said’s net impact on LW in response to something that comes from a single source I can’t check.

(But, in response to your outright accusation of dishonesty at the end: if I said the thing you would prefer me to say, it would be an untruth; my opinion of Duncan is not what you imply it is. My opinion of my wife, even less so, but I assume the point here is the application to the present case.)

That’s fair—I should not have accused you of dishonesty, and I apologize.

I have heard both, the latter maybe 2x as often as the former?

I think that what’s happening right now, and has been happening over the years, is that the message “this is the kind of engagement we do, here” has been sent over and over again, and the mass of users has responded accordingly. I think if that message stopped being sent, or if a strong countersignal was sent, the mass of users would again respond accordingly.

I can’t model Eliezer very well, but I’d argue that Eliezer is responsible for that decision. Whether it’s because he gets more reach elsewhere, less annoying diagreement/pointing out flaws, or what, it’s on him, not on any individual poster. I give him a ton of credit (and Robin Hanson) for starting LessWrong, but I reject any implication that we should limit or prune LessWrong to make it more appealing to Eliezer. Multiplied by a lot if Eliezer isn’t directly asking for some change, and we’re just cargo-culting what it looked like a decade ago.

I chose Eliezer as one example; it would be a mistake to think that my overall point was about Eliezer.

This single individual (who was recently making a big deal about being non-banned/in good standing) is more responsible than any other single individual for driving away more than a dozen high-quality authors; is the most-frequently cited reason, as far as I can tell, when high-quality people are asked to be specific about why they’re not on LessWrong/what makes LessWrong a miserable place to try to share their ideas and co-think.

Hearing that they’re tolerated because they maintain GreaterWrong makes my CFAR instincts tingle and makes me want to teach people about goal factoring.

Fair enough. I bounce off a lot of posts and comments, so I probably do some amount of victim-blaming if someone over-weights criticism, especially if it’s annoying and wrong. I don’t see how one or a few posters can move the site from well-worth posting to negative value, though it certainly could change the sign for a very marginal decision.

Even so, unless the problematic posts and comments are getting downvoted, but somehow still in-your-face enough to drive someone away, it’s hard to see that banning or otherwise authoritatively controlling the poster is justified.

Er, the (somewhat fuzzy) thesis of the post is that there’s a thing where, like, one or two prominent Socrati set the vibe, and then a bunch of other people follow suit; I find that criticism on LW feels more like [that guy] + [100 emulators of his style of engagement] than it used to.

Ultimately, it isn’t about just that one person’s engagement (although as I note above, they seem to have an outsized direct impact) so much as it is about a … prion disease?

As someone who’s posted about 60 or 70 essays on LW over the past eight years, doing so in 2023 involves a lot of bracing, as if I were hyping myself up to grab an electric fence. I straightforwardly expect the experience of posting to involve a net-negative subsequent four days. This was not the case in e.g. the Conor Moreton days, even though one or two of the Conor Moreton essays ended up in net negative territory.

If it’s that rough for me, when I’m a good writer who’s confident in his insights and has a lot of people who are interested-by-default in his thoughts, I imagine it can get a lot harder for the twenty-year-old not-yet-known version of me.

My recollection is that “Conor Moreton” at least once wrote something along the lines of “I find writing for LW stressful because I get a lot of criticism”. Maybe I’m misremembering, and for sure the obvious guess would be that you remember more clearly than I do, but my recollection now of my impression then is that it was nearer than you’re suggesting to how you describe your present experience of posting on LW.

Oh, I’ve definitely found it somewhat stressful all along; I think I’m in the most sensitive quintile if not decile.

Sorry, didn’t mean to imply that the shift was from [zero] to [large number]. More wanted to gesture at a shift from [moderate number] to [large number].

Like, there’s the difference between viscerally expecting one in four essays to result in a negative experience of magnitude 10 lasting for a day or two, and viscerally expecting two in three essays to result in a negative experience of magnitude 30 lasting for four days.

If the “ban commenter” function had not been implemented, I wouldn’t have posted any of my last five or six essays, and would be already gone.

Ah, I see. I don’t really disagree, but I also don’t think LW is unique in this, nor that there is (or can be) a long-lived growing-popularity group that maintains the feel of the early days. This seems like an evolution that’s plagued old-timers of a medium for all time, from SF fandom to pre-internet BBSs and Usenet, to early-internet special-purpose forums, to LW and rationalist-adjecent fora.

I don’t think Duncan’s gesturing at the “eternal September” problem—I think he’s talking about the “toxic low-grade criticism” problem, which is a related but separate issue. A persistent culture of toxic low-grade criticism exacerbates the eternal September problem by allowing impressionable newcomers to become acculturated to the pre-existing toxic dynamic, or to self-select for compatibility with it, making it that much harder to deal with. But you can work on improving the culture while also admitting that the constant influx of newcomers may make it difficult to go as far as you’d like to in terms of creating a specific and consistent set of norms.

I think there are some differences between this and other instances of degradation of quality by growth and entry of less-hardcore newcomers, and a resulting shift in norms that are generally negative in terms of quality. But I think there are a lot more similarities than differences.

I repeat that I did not say and did not mean that anyone is “tolerated because they maintain GreaterWrong”.

I affirm that you did not say it, and believe that you did not mean it.

I would bet $100 to someone’s $1 that, if we could check the other timeline where that person behaved exactly the same way in comments, but had not made GreaterWrong, they would’ve been banned years ago.

(I believe this in part because I’ve heard multiple mods across multiple years talk about wanting to ban that person specifically, and I’ve heard GreaterWrong raised explicitly as cause for hesitation in something like four out of seven such discussions.)

I can’t think of any way to operationalize that bet—other than maybe noting that you have some of the same objections to Zack as to Said, and Zack also has not been banned; but to my mind their styles of interaction on LW are quite different and I can easily imagine someone finding one of them clearly net positive and the other clearly net negative. I guess we could ask the moderators, but they might very reasonably not want to answer that question, and you might fairly reasonably not trust whatever answer they gave.

If we could operationalize it, though, I think I would be quite happy taking the other side of it. 100:1 feels way overconfident to me.

Oh, to be clear: I don’t think Zack should be banned from LW. I’d prefer to never interact with him at all, but as noted elsewhere, I’m perfectly happy to stay in my corner and leave him alone over in his.

(I also can’t think of any way to operationalize the bet.)

Lucky, I have a comment saved to that exact effect, as I have been workshopping a community dynamics post for a long time about a related dynamic:

> I don’t intend to ban you any time soon, because I really value your place in this community—you’re one of the few people to build useful community infrastructure like ReadTheSeqeunces.com and the UI of GreaterWrong.com, and that’s been one of the most salient facts to me throughout all of my thinking on this matter. (Ben Pace, 5 years ago now according to the timestamp)

Wait, the only thing I remember Said and Eliezer arguing about was Eliezer’s glowfic. Eliezer dropped out of LW over an argument about how he was writing about tabletop RPG rules in his fanfiction?

Eliezer wasn’t posting much on LW before then, unless I’m misremembering badly, so if (1) you’re right about that being the only substantial argument between Eliezer and Said and (2) Duncan’s claim is specifically that Eliezer avoids LW because of unpleasant interactions he’s had with Said (as opposed to e.g. because he’s observed how Said interacts with others and doesn’t want to risk joining their number) then something doesn’t add up.

fyi I don’t have a belief that Eliezer avoids the site because of Said-in-particular (although I think he does generally avoid the site because it’s unhedonic). I think a couple things maybe got conflated here.

(For anyone else curious, that thread is here.)

I do want to note, if this post (or at least many of the comments) are basically arguing about one particular person who’s blocked from commenting, I do have a different take on it than my usual opinion on authors-get-to-block-whoever.

I haven’t currently had enough time to think through this that explicitly and form a considered opinion, but, just flagging this for now. (It’s a bit confusing that thing to ask for here, given our existing tooling. I might create a new top-level post that’s like “actually hash out the object level”)

Update: I don’t know if this is a great solution but for immediate future I declare this comment on comment on “LW Team is adjusting moderation policy” to be a place where a) I’ll be putting my own thoughts on this topic when I have time, and b) Said is welcome to argue.

I tried to refrain from getting specific, but did not feel like it was correct to bar others from getting specific, nor to refuse to respond to them.

I would probably be accused of being part of the sorts of counterproductive criticism you are talking about in your post. I am trying to think whether I have ever faced the sort of criticism myself on LessWrong. I’ve written quite a few posts that have received a significant amount of attention, e.g.:

Are smart people’s personal experiences biased against general intelligence?

Instrumental convergence is what makes general intelligence possible

Latent variables for prediction markets: motivation, technical guide, and design considerations

Random facts can come back to bite you

What sorts of preparations ought I do in case of further escalation in Ukraine?

🤔 Coordination explosion before intelligence explosion...?

Towards a comprehensive study of potential psychological causes of the ordinary range of variation of affective gender identity in males

Maybe I’ve just been lucky, but I guess at least in that case it seems like the base rate for being unlucky is fairly low.

A kind of unfortunate thing about Zack’s response is that he follows the LessWrong taboo on politically charged examples, and that makes it unclear what kinds of disagreements he has in mind in his post. To familiarize yourself with it, you can take a look at Containment Thread on the Motivation and Political Context for My Philosophy of Language Agenda, but the TL;DR is that leaders in the rationalist community have often been acting in bad faith wrt. trans issues.

This sort of situation makes calls for assumptions of good faith a threat to Zack, because such calls undermine creating common knowledge about what situation he is in. If you want to be able to make calls for good faith assumptions without triggering Zack, I think the best approach would be to restore good faith by pushing rationalist leaders to make amends to Zack if you have any leverage within the rationalist community. (After all, we certainly can’t assume good faith when there’s clear bad faith going on.) And to come up with structural solutions to prevent it from happening again.

More generally, one thing that can be done to prevent these sorts of traumas from building up is taking more care to resolve objections/complaints. If someone has an issue with something you are doing/saying, then there’s a good chance you are doing/saying something wrong, and by listening to them and correcting yourself, you can eliminate the complaint in a mutually satisfying way.

Gonna bring up another case where someone was critical on LessWrong: someone advocated for socialist firms and I (being critical) spot-checked claims about employee engagement and coop productivity. Does the “Killing Socrates” point apply to my comments here? Why/why not?

Personally, I think those comments are good.

In the first, you take a place where someone has cited very specific numbers, and ask them to (basically) say where those numbers came from. Then, you note note a problem with the claim “if [socialist] then [more productive]” by pointing out that socialist firms haven’t come to dominate the economy.

In the second, you accommodate the other user’s request that you target your spot-check to co-ops, note that your spot-check led you to the opposite conclusion of the other user, and also note a confusion about whether the cited study is even coherent.

I think this is extremely standard, central LW skepticism in its healthy form.

Some things those comments do not do:

Attempt to set the frame of the discussion to something like ~”obviously this objection I have raised is fundamentally a defeater of your whole point; if you do not answer it satisfactorily then your thesis has been debunked,” which is a thing that Socrati tend to do to a pretty substantial degree.

Leap to conclusions about what the author meant, or what their point is tantamount to, and then run off toward the horizon without checking back in. You’re just straightforwardly expressing confusions and curiosities, not putting words in the author’s mouth.

Create a large burden-of-response upon the author. They’re pretty atomic, simple points; each could be replied to without the author having to do the equivalent of writing a whole new essay.

Cause a tree-explosion where, like, the response to Objection A generates Objections B and C, and then the response to Objection B generates Objections D and E, and then the response to Objection C generates Objections F, G, and H, all without a) consideration for whether the other person intends to go that deep, or b) consideration for whether the Objections are anywhere near the crux of the issue.

I apologize; this comment is sort of dashed off and I would’ve liked to have an additional spoon for it; I don’t think I’ve been exhaustive or thorough. But hopefully this gives at least a little more detail.

So maybe a better example of the problem you are talking about is this, where I basically end up in a position of “if you cannot give an explanation of how this neurological study supports your point, then your point is obscurantist? My behavior in this thread could sort of be said to contain all four of the issues you mention. However rereading the original post and thread makes me feel like it was pretty appropriate. There were some things I could have done better, but my response was better than nothing, despite ultimately being a criticism.

I think that sometimes it is true that you and a conversational partner will be in a situation where it really actually seems like the highest-probability hypothesis, by a high margin, is that they can’t explain because their point has no merit.

I think one arrives at such a high probability on such a sad hypothesis due to specific kinds of evidence.

I think that often, people are overconfident that that’s what’s going on, and undercounting hypotheses like “the person wants to have the conversation at a different level of meta” or “they just do not have the time to reply to each of ten different commenters who are highly motivated to spill words” or “the person asking for the explanation is not the kind of person the author is trying to bridge with or convince.”

(This is near the root of my issues with Said—I don’t find Said’s confusions at all predictive or diagnostic of confusion-among-my-actual-audience; Said seems to think that his own lack of understanding means something about the point being confused or insufficiently explained or justified, and I often simply disagree, and think that it’s a him-problem.)

I think that it’s good to usually leave space for people, as a matter of policy—to try not to leave the impression that you think (and thus others should think) that a failure to respond adequately is damning, except where you actually for-real think that a failure to respond adequately is genuinely damning.

Like, it’s important not to whip that social weapon out willy-nilly, because then it’s hard to tell when no, we really mean it, if they can’t answer this question we should actually throw out their claims.

Currently, the environment of LW feels, to me, supersaturated with that sort of implication in a way that robs the genuine examples of their power, similar to how if people refer to every little microaggression as “racism” then calling out an actual racist being actually macro-racist becomes much harder to do.

I don’t think it’s bad or off-limits to say that if someone can’t answer X, their point is invalid, but I think we should reserve that for when it’s both justified and actually seriously meant.

I think that’s a very interesting list of points. I didn’t like the essay at all, and the message didn’t feel right to me, but this post right here makes me a lot more sympathetic to it.

(Which is kind of ironic; you say this comment is dashed off, and you presumably spent a lot more time on the essay; but I’d argue the comment conveys a lot more useful information.)

Indeed: and many many people have issue with what the-LW-users-euphemized-as-Socrates are doing, and they are utterly recalcitrant to change.

Hm...

I mean you’re not 100% wrong that the dissatisfaction indicates that there’s some sort of problem somewhere. I think my counterarguments are also not 100% wrong though.

Maybe the issue is that we are both jumping to conclusions without fully mapping out the underlying issues. Like I mostly don’t know which people have gotten run off LessWrong, nor which interactions caused them to get run off. Maybe a list of examples could help clarify why their experience differs from mine, as well as clarify whether there’s any alternatives to “less LessWrong critics” and “less LessWrong authors” to solve the problem (e.g. maybe standardizing some type of confidence indicators or something could help, hypothetically).

(Though that’s the issue, right? Your point is that mapping out the issue is too much work. So it’s not gonna get done. Maybe the Lightcone LW team could sponsor the mapping? Idk.)

I think there is a simple solution: the people who are currently getting quietly pissed at the Socrati, or who are sucking it up and tolerating them, stop doing so. They start criticizing the criticism, downvoting hard, upvoting the non-Socrati just to correct for the negativity drip, and banning the most prolific Socrati from commenting on their posts.

Instead of laboriously figuring out whether a problem exists, the people for whom Socrati are a problem can use the tools at their disposal to fight back/insulate themselves from worthless and degrading criticism.

Or the Socrati could, you know, listen to the complaints and adjust their behavior. But I don’t see that or some sort of LW research into the true feelings of the frustrated expats actually happening, and I think the best alternative is just to have people like Duncan who are frustrated with the situation just being a lot more vocal and active.

One reason I want more people to know about and use the ban-from-my-post feature is so the mod team* can notice patterns in who gets banned by individuals. Lots of people are disinclined to complain, especially if they believe Socrates is the site culture, censuses of people who quietly left are effort intensive and almost impossible to make representative, but own-post banning is an honest signal that aligns with people’s natural incentives.

*Technically I’m on the mod team but in practice only participate in discussions, rather than take direct action myself.

I think my claim is more “there are genuine competing access needs between Socrati and Athenians, they fundamentally cannot both get all of what they want,” + a personal advocating-for-having-the-Athenians-win, à la “let’s have a well-kept garden.”

I mean that’s your conclusion. But your claim is that the underlying problem/constraint that generates this conclusion is that the Socrati raise a bunch of doubts about stuff and it’s too much work for the Athenians to address those doubts.

Like you say the Athenians have the need for trust so they can build things bigger than themselves, and the Socrati have the need for being allowed to freely critique so they can siphon status by taking cheap shots at the Athenians. And these needs conflict because the cheap shots create a burden on the Athenians to address them.

Like to me the obvious starting point would be to list as many of the instances of this happening as possible and to better get a picture of what’s going on. Which writers are we losing, what writings have they contributed with, and what interactions made them leave? But this sort of rigorous investigation seems kind of counter to the spirit of your complaint.

Nnnnot quite; that’s not the analogy I intended to Athens.

Rather, what I’m saying is that the Socrati make the process of creating and sharing thoughts on LW much more costly than it otherwise would be, which drives authors away, which makes LW worse.

I don’t want to betray confidences or put words in other people’s mouths, but I can say that I’ve teetered on the verge of abandoning LW over the past couple of months, entirely due to large volumes of frustratingly useless and soul-sucking commentary in the vein of Socrates, one notable example being our interactions on the Lizardman post.

I’m not sure what is the essential difference you are highlighting between your description of the analogy and my description.

Maybe you can ping the people involved and encourage them to leave a description of their experiences here if they want?

I still think I had a reasonable point with my comments on the lizardman post, and Zack’s response to your post seems to be another example along the lines of my post.

It seems to me that the basic issue with your post is that you were calling for assumptions of good faith. But good faith is not always present, and so this leads to objections from the people who have faced severe bad faith.

If you don’t want objections to calls for good faith assumptions, you really gotta do something to make them not hit the people who face bad faith so hard. For instance, I would not be surprised if Zack would have appreciated your post if you had written “One exception is trans issues, where rationalist leaders typically act in bad faith. See Zack’s counters. Make sure to shame rationalist leaders for that until they start acting in good faith.”.

Of course, then there’s the possibility that your call for good faith hits other people than Zack, e.g. AFAIK there’s been some bad faith towards Michael Vassar. But if you help propagate information about bad faith in general, then in general people who face bad faith won’t have reasons to attack your writings.

In the long run, this would presumably incentivize good faith and so make calls for good faith assumptions more accurate.

That’s optimizing appearances in response to a bug report, instead of fixing the issue, making future bug detection harder. A subtly wrong claim that now harms people less is no less wrong for it.

What does “fixing the issue” mean in your model? Could you give an example of a change that would genuinely fix the issue?

I more think of my proposal as propogating the bug report to the places where it can get fixed than as optimizing for appearances.

Not making that claim as a claim of actuality. It could instead be pursued to the same effect as a hypothetical claim, held within a frame of good faith. Then the question of the frame being useful becomes separate from the question of the claim being true, and we can examine both without conflating them, on their own merits.

A frame in this context is a simulacrum/mask/attitude, epistemically suspect by its nature, but capable of useful activity as well as of inspiring/refining valid epistemic gears/features/ideas that are applicable outside of it. When you are training for an ITT, or practicing Scott Alexander’s flavor of charity, you are training a frame, learning awareness of the joints the target’s worldview is carved at. Being large and containing multitudes is about flitting between the frames instead of consistently being something in particular.

That’s an alternate approach one could take to handling the claim, though I don’t see how it’s less optimizing for appearances or more fixing the issue.

Saying “2+2=5 is a hypothetical claim” instead of “2+2=5 actually” is not a wrong claim optimizing for appearances, the appearances are now decisively stripped. It fixes the issue of making an unjustified claim, doesn’t fix the issue of laboring under a possibly false assumption, living in a counterfactual.