Content warning: About an IRL death.

Today’s post isn’t so much an essay as a recommendation for two bodies of work on the same topic: Tom Mahood’s blog posts and Adam “KarmaFrog1” Marsland’s videos on the 2010 disappearance of Bill Ewasko, who went for a day hike in Joshua Tree National Park and dropped out of contact.

2010 – Bill Ewasko goes missing

Tom Mahood’s writeups on the search [Blog post, website goes down sometimes so if the site doesn’t work, check the internet archive]

2022 – Ewasko’s body found

ADAM WALKS AROUND Ep. 47 “Ewasko’s Last Trail (Part One)” [Youtube video]

ADAM WALKS AROUND Ep. 48 “Ewasko’s Last Trail (Part Two)” [Youtube video]

And then if you’re really interested, there’s a little more info that Adam discusses from the coroner’s report:

(I won’t be fully recounting every aspect of the story. But I’ll give you the pitch and go into some aspects I found interesting. Literally everything interesting here is just recounting their work, go check em out.)

Most ways people die in the wilderness are tragic, accidental, and kind of similar. A person in a remote area gets injured or lost, becomes the other one too, and dies of exposure, a clumsy accident, etc. Most people who die in the wilderness have done something stupid to wind up there. Fewer people die who have NOT done anything glaringly stupid, but it still happens, the same way. Ewasko’s case appears to have been one of these. He was a fit 66-year-old who went for a day hike and never made it back. His story is not particularly unprecedented.

This is also not a triumphant story. Bill Ewasko is dead. Most of these searches were made and reports written months and years after his disappearance. We now know he was alive when Search and Rescue started, but by months out, nobody involved expected to find him alive.

Ewasko was not found alive. In 2022, other hikers finally stumbled onto his remains in a remote area in Joshua Tree National Park; this was, largely, expected to happen eventually.

I recommend these particular stories, when we already know the ending, because they’re stunningly in-depth and well-written fact-driven investigations from two smart technical experts trying to get to the bottom of a very difficult problem. Because of the way things shook out, we get to see this investigation and changes in theories at multiple points: Tom Mahood has been trying to locate Ewasko for years and written various reports after search and search, finding and receiving new evidence, changing his mind, as has Adam, and then we get the main missing piece: finding the body. Adam visits the site and tries to put the pieces together after that.

Mahood and Adam are trying to do something very difficult in a very level-headed fashion. It is tragic but also a case study in inquiry and approaching a question rationally.

(They’re not, like, Rationalist rationalists. One of Mahood’s logs makes note of visiting a couple of coordinates suggested by remote viewers, AKA psychics. But the human mind is vast and full of nuance, and so was the search area, and on literally every other count, I’d love to see you do better.)

Unknowns and the missing persons case

Like I said, nothing mind-boggling happened to Ewasko. But to be clear, by wilderness Search and Rescue standards, Ewasko’s case is interesting for a couple reasons:

First, Ewasko was not expected to be found very far away. He was a 65-year-old on a day hike. But despite an early and continuous search, the body was not found for over a decade.

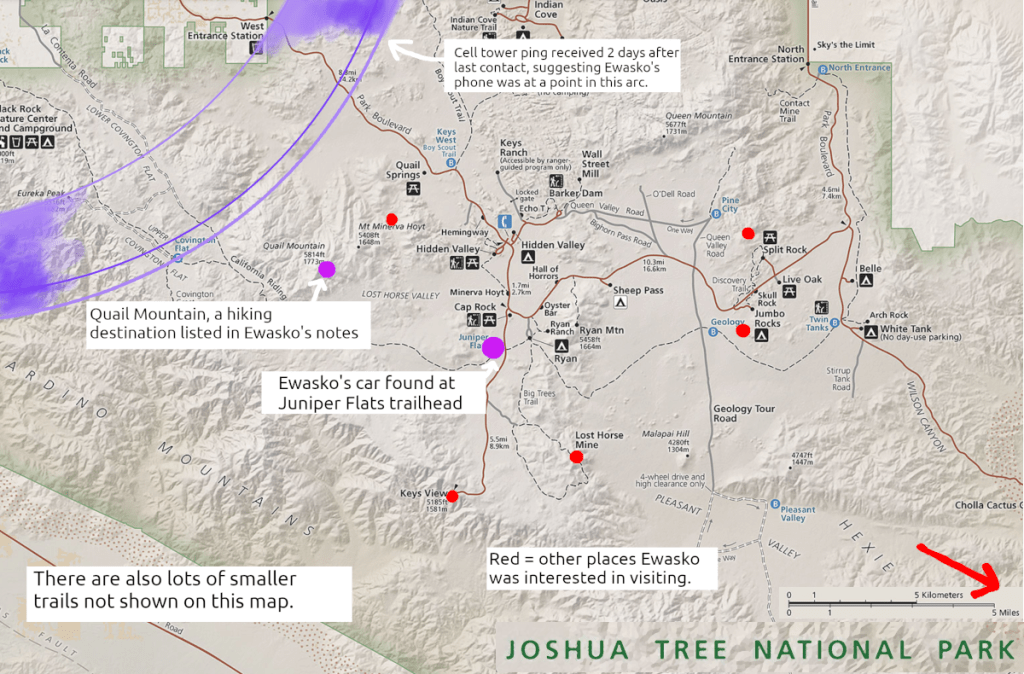

Second, two days after he failed to make a home-safe call to his partner and was reported missing, a cell tower reported one ping from his cell phone. It wasn’t enough to triangulate his location, but the ping suggested that the phone was on in a radius of approximately 10.6 miles around a specific cell tower. The nearest point of that radius was, however, miles in the opposite direction from the nearest likely trail destination to Ewasko’s car—from where Ewasko ought to be.

If you’ve spent much time in wilderness areas in the US, you know that cell coverage is findable but spotty. You’ll often get reception on hills but not in valleys, or suchlike. There’s a margin for error on cell tower pings that depends on location. Also, in this case, Verizon (Ewasko’s carrier) had decent coverage in the area – so it’s kind of surprising, and possibly constrains his route, that his cell phone only would have pinged once.

All of this is very Bayesian: Ewasko’s cellphone was probably turned off for parts of his movement to save battery (especially before he realized he was in danger), maybe there was data that the cell carrier missed, etc, etc. But maybe it suggests certain directions of travel over others. And of course, to have that one signal that did go out, he has to have gotten to somewhere within that radius – again, probably.

How do you look for someone in the wilderness?

Search and rescue – especially if you are looking for something that is no longer actively trying to be found, like a corpse – is very, very arduous. In some ways, Joshua Tree National Park is a pretty convenient location to do search and rescue: there aren’t a lot of trees, the terrain is not insanely steep, you don’t have to deal with river or stream crossings, clues will not be swept away by rain or snow.

But it’s not that simple. The terrain in the area looks like this:

There are rocks, low obstacles, different kinds of terrain, hills and lines of sight, and enough shrubbery to hide a body.

A lot of the terrain looks very similar to other parts of the terrain. Also dotted about are washes made of long stretches of smooth sand, so the landscape is littered with features that look exactly like trails.

Also, environmentally, it’s hot and dry as hell, like “landscape will passively kill you”, and there are rattlesnakes and mountain lions.

When a search and rescue effort starts, they start by outlining the kind of area in which they think the person might plausibly be in. Natural features like cliffs can constrain the trails, as can things like roads, on the grounds that if a lost person found a road, they’d wait by the road.

You also consider how long it’s been and how much water they have. Bill Ewasko was thought to have three bottles of water on him – under harsh and dry circumstances, that water becomes a leash, you can only go so far with what you have. A person on foot in the desert is limited in both time and distance by the amount of water they carry; once that water runs out, their body will drop in the area those parameters conscribe.

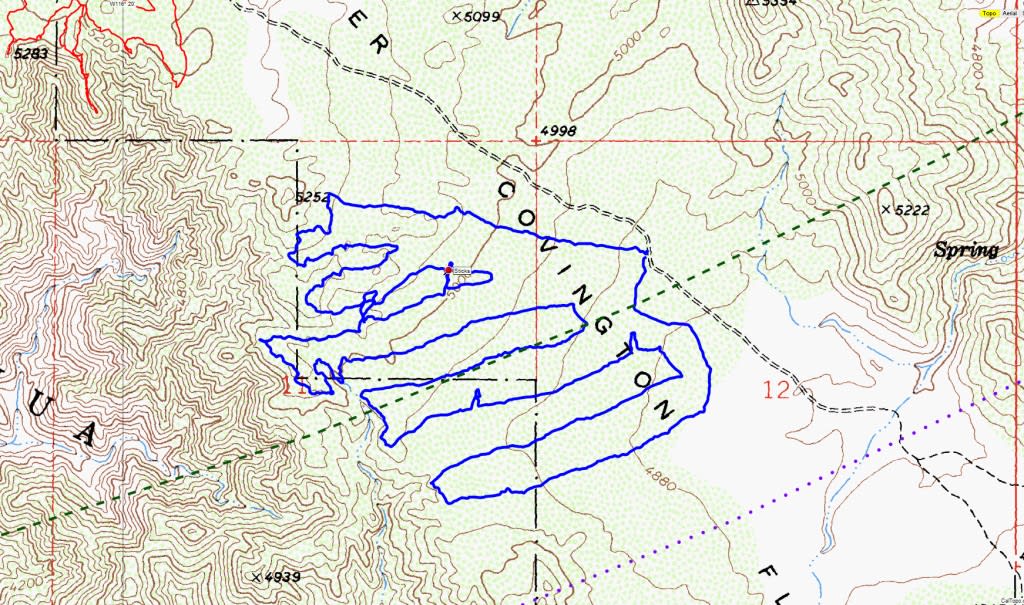

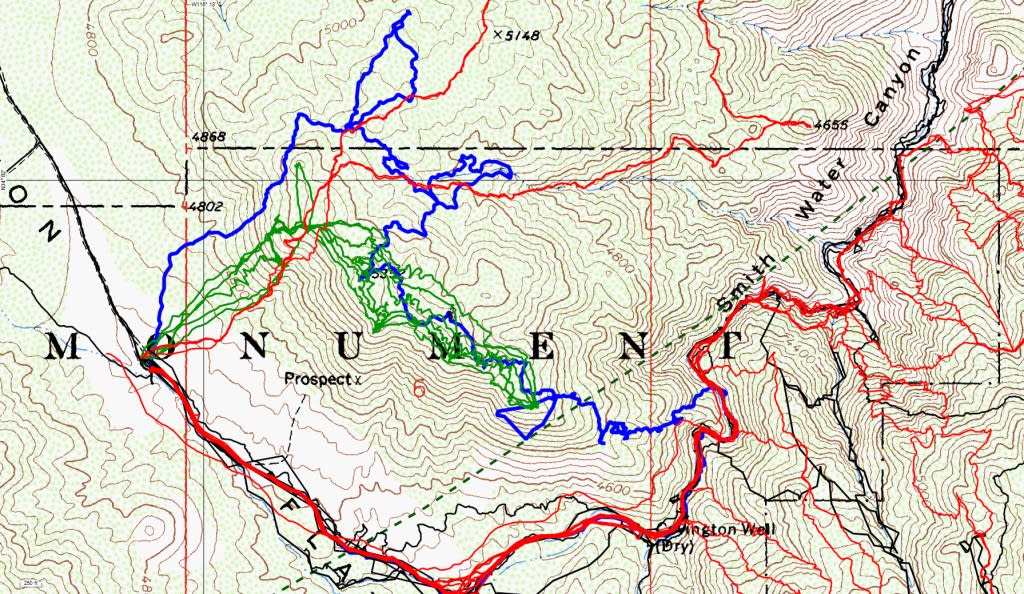

Starting from the closest, most likely places and moving out, searchers first hit up the trails and other clear points of interest. But once they leave the trail? Well, when they can, maybe they go out in an area-covering pattern, like this:

But in practice, that’s not always tenable. Maybe you can really plainly see from one part to another and visually verify there’s nothing there. Maybe this wouldn’t get you enough coverage, if there are obstacles in the way. There are mountains and cliff faces and rocky slopes to contend with.

Also, it’s pretty hard to cover “all the trails”, since they connect to each other, and someone is really more likely to be near a trail than far away from a trail. Or you might have an idea about how they would have traveled – so do you do more covering-terrain searching, or do you check farther-out trails? In this process, searchers end up making a lot of judgment calls about what to prioritize, way more than you might expect.

You end up taking snaky routes like this:

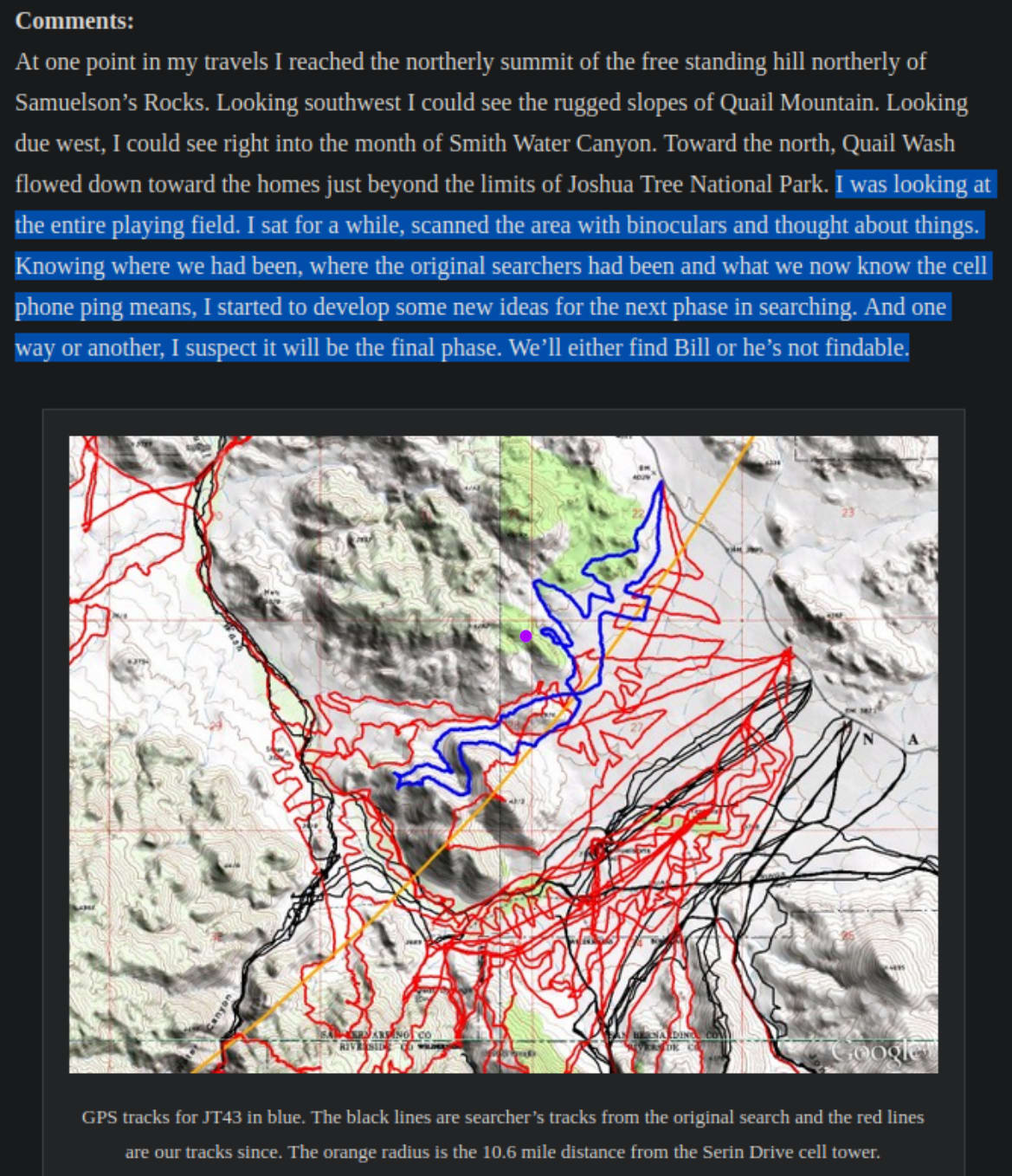

The initial, official Search and Rescue was called off after about a week, so the efforts Mahood records – most of which he is doing himself, or with some buddies – constitute basically every search that happened. He posts GPS maps too, of that day’s travels overlaid on past travels. You see him work outward, covering hundreds of miles, filling in the blank spots on the map.

Mahood is really good at both being methodical and explaining his reasoning for each expedition he makes, and where he thinks to look. It’s an absolutely fascinating read.

43 expeditions in, in December 2012, Mahood writes this:

The purple dot is my addition. This is where Ewasko’s body was found in 2022. Mahood wrote this about the same trip where (as far as I can tell) he came the closest any searcher ever got to finding Ewasko. Despite saying it was the end game, Mahood and associates mounted about 50 more trips. Hindsight is heartbreaking.

Making hindsight useful

Hindsight haunts this story in 2024. It’s hard to learn about something like this and not ask “what could have stopped this from happening?”

I found myself thinking, sort of automatically, “no, Ewasko, turn around here, if you turn around here you can still salvage this,” like I was planning some kind of cross-temporal divine intervention. That line of thinking is, clearly, not especially useful.

Maybe the helpful version of this question, or one of them, is: If I were Ewasko, knowing what Ewasko knew, what kind of heuristics should I have used that would have changed the outcome?

The answer is obviously limited by the fact that we don’t know what Ewasko did. There are some specifics, like that he didn’t tell his contacts very specific hiking plans. But he was also planning on a day hike at an established trailhead in a national park an hour outside of Palm Springs. Once he was up the trail, you’ll have to watch Adam’s video and draw your own conclusions (if Adam is even right.)

Mahood writes: “People seldom act randomly, they do what makes sense to them at the time at the specific location they are at.”

And Adam says: “Most man-made disasters don’t spring from one bad decision but from a series of small, understandable mistakes that build on one another.”

Another question is: If I were the searchers, knowing what the searchers know, what could I have done differently that would have found the body faster?

Knowing how far away the body was found and the kind of terrain covered, I’m still out on this one.

How deep the search got

Moving parts include:

Concrete details about Ewasko (Ewasko’s level of fitness, his supplies, down to the particular maps he had, what his activities were earlier in the day)

Ewasko’s broader mindset (where he wanted to go at the outset, which tools he used to navigate trails, how much HE knew about the area)

Ewasko’s moment-to-moment experience (if he were at a particular location and wanted to hurry home, which route would he take? What if he were tired and low on water and recognized he was in an emergency? What plans might he make?) (This ties into the field of Search and Rescue psychology – people disoriented in the wilderness sometimes make predictable decisions.)

Physical terrain (which trails exist and where? How hard is it to get from places to place? What obstacles are there)

Weather (how much moonlight was there? How hard was travelling by night? How bad was the daytime heat?)

Electromagnetic terrain (where in the park has cell service?)

Electromagnetic interpretation (How reliable is one reported cell phone ping? If it is inaccurate, in which ways might it be inaccurate?)

Other people’s reports (the very early search was delayed because a ranger apparently just repeatedly didn’t see or failed to notice Ewasko’s car at a trailhead, and there were conflicting reports about which way it was parked. According to Adam and I think Mahood, it now seems now like the car was probably there the entire time it should have been, and it was probably just missed due to… regular human error. But if this is one of the few pieces of evidence you have, and it looks odd – of course it seems very significant.)

The search evolving over time (where has been looked in what ways before? And especially as the years pass on – some parts of the terrain are now extremely well-searched, not to mention are regularly used by regular hikers. What are the changes one of these searches missed somewhere, vs. that Ewasko is in a completely new part of the territory?)

I imagine that it would be really hard to choose to carry on with something like this. In this investigation, there was really no new concrete evidence between 2010 and 2022. As Mahood goes on, in each investigation, he adds the tracks to his map. Territory fills in – big swathes of trails, each of them. New models emerge, but by and large the only changing detail is just that you’ve checked some places now, and he’s somewhere you haven’t checked. Probably.

A hostile information environment

Another detail that just makes the work more impressive: Mahood is doing all these investigations mostly on his own, without help and with (as he sees it, although it’s my phrasing) dismissal and limited help from Joshua Tree National Park officials. The reason Mahood posted all of this on the internet was, as he describes it, throwing up his hands and trying to crowd-source it, asking for ideas.

Then after that—The internet has a lot of interested helpful people – I first ran into Mahood’s blog months ago via r/RBI (“Reddit Bureau of Investigation”) or /r/UnsolvedMysteries or one of those years ago. I love OSINT, I think Mahood doing what he did was very cool. But also on those sites and also in other places there are also a lot of out-there wackos. (I know, wackos on the internet. Imagine.) In fact there’s a whole conspiracy theory community called Missing 411 about unexplained disappearances in national parks, which attributes them vaguely to sinister and/or supernatural sources. I think that’s all probably full of shit, though I haven’t tried to analyze it.

Anyway, this case attracted a lot of attention among those types. Like: What if Bill Ewasko didn’t want to be found? What if someone wanted to kill him? What if the cellphone ping was left by as an intentional red herring? You run into words like “staged” or “enforced disappearance” or “something spooky” in this line of thought, so say nothing of run-of-the-mill suicide.

Look, we live in a world where people get kidnapped or killed or go to remote places to kill themselves sometimes, the probability is not zero. Also – and I apologize if this sounds patronizing to searchers, I mean it sympathetically – extended fruitless efforts like this seem like they could get maddening, that alternative explanations that all your assumptions are wrong would start looking really promising. Like you’re weaving this whole dubious story about how Ewasko might have gone down the one canyon without cell reception, climbing up and down hills in baking heat while out of water and injured—or there’s this other theory, waving its hands in the corner, going yeah, OR he’s just not in the park at all, dummy!

Its apparent simplicity is seductive.

Mahood apparently never put much stock in these sort of alternate models of the situation; Adam thought it was seriously likely for a while. I think it’s fair to say that “Ewasko died hiking in the park, in a regular kind of way” was always the strongest theory, but it’s the easiest fucking thing in the world for me to say that in retrospect, right? I wasn’t out there looking.

Maps and territories

Adam presents a theory about Ewasko’s final course of travel. It’s a solid and kind of stunning explanation that relies on deep familiarity with many of the aforementioned moving factors of the situation, and I do want you to watch the video, so go watch his video. (Adam says Mahood disagrees with him about some of the specifics – Mahood at present hasn’t written more after the body was found, but he might at some point, so keep an eye out.)

I’ll just go talk a little about one aspect of the explanation: Adam suspects Ewasko got initially lost because of a discrepancy between the maps at the time and the on-the-ground trail situation. See, multiple trails run out of the trailhead Ewasko parked at and through the area he was lost in, including official park-made trails and older abandoned Jeep trails.

Adam believes that partly as a result of the 1994 Desert Protection Act, Joshua Tree National Park was trying to promote the use of their own trails, as an ecosystem conservation method. Ewasko believes that Joshua Tree issued guidance to mapmakers to not mark (or de-prioritize marking) trails like the old Jeep roads, and to prioritize marking their official trails, some of which were faint and not well-indicated with signage.

Adam thinks Ewasko left the parking lot on the Jeep road – which, to be fair, runs mostly parallel to the official trail, and rejoins to it later. But he thinks that Ewasko, when returning, realized there was another parallel trail to the south and wanted to take a different route back, causing him to look for an intersection. However, Ewasko was already on the southern trail, and the unlabeled intersection he saw was to another trail that took him deeper into the wilderness – beginning the terrible spiral.

Think of this in terms of Type I and Type II errors. It’s obvious why putting a non-existent trail on a map could be dangerous: you wouldn’t want someone going to a place where they think there is a trail, because they could get lost trying to find it. It’s less obvious why not marking a trail that does exist could be dangerous, but it may well have been in this case, because it will lead people to make other navigational errors.

Endings

The search efforts did not, per se, “work”. Ewasko’s body was not found because of the search effort, but by backpackers who went off-trail to get a better view of the sunset. His body was on a hill, about seven miles northeast of his car, very close to the cellphone ping radius. He was a mile from a road.

In Adam’s final video, on Ewasko’s coroner’s report, Adam explaining that he doesn’t think he will ever learn anything else about Ewasko’s case. Like, that he could be wrong about what he thinks happened or someone may develop a better understanding of the facts, but there will be no new facts. Or at least, he doubts there will be. There’s just nothing left likely to be found.

There are worse endings, but “we have answered some of our questions but not all of them and I think we’ve learned all we are ever going to learn” has to be one of the saddest.

Like I said, I think the searchers made an incredible, thoughtful effort. Sometimes, you have a very hard problem and you can’t solve it. And you try very hard to figure out where you’re wrong and how and what’s going on and what you do is not good enough.

These reports remind me of the wealth of material available on airplane crashes, the root cause analyses done after the fact. Mostly, when people die in maybe-stupid and sad accidents, their deaths do not get detailed investigations, they do not get incident reviews, they do not get root cause analyses.

But it’s nice that sometimes they do.

If you go out into the wilderness, bring plenty of water. Maybe bring a friend. Carry a GPS unit or even a PLB if you might go into risky territory. Carry the 10 essentials. If you get lost, think really carefully before going even deeper into the wilderness and making yourself harder to find. And tell someone where you’re going.

Crossposted to: eukaryotewritesblog.com | Substack | LessWrong

I really enjoyed this, thanks for linking it.

Curated. This was a great recommendation and a very readable account of an ultimately failed attempt to find a missing person. I was drawn in by eukaryote’s description of the case and, especially, the processes of the searchers. I watched some of the linked videos and sampled some blog posts. (It has also made me feel a little rueful about my time traipsing through washes in the Colorado Desert by moonlight – though in my case it was a bit more populated).

I feel a bit of pressure to precipitate out some kind of neat rationality takeaway from the story of this search. For example, the park management’s Simulacrum II decision to distort a shared map maybe lead to tragedy (which I think is pretty plausible to anyone who has tried to use directions that don’t indicate the turnings you shouldn’t take).

But, I think there’s not one neat takeaway. It’s a story of trying to carefully build a model of the situation and trying to figure out what hypotheses fit that model, and dealing with the slow drip of inconclusive data. I think it’s pretty valuable to read the logs of how people actually tried to reason through the problems they faced, and as eukaryote writes, “Mahood is really good at both being methodical and explaining his reasoning for each expedition he makes, and where he thinks to look”.

One moment in Marsland’s video really stuck out to me: he is finishing a hike that matched Ewasko’s planned routes. The conditions are similar. And as he talks to the camera, he’s very visibly slurring and affected by the heat. It’s gotta be pretty hard to think under those conditions? I wonder if whatever rationality I have will still work for me when I’m so depleted.

And of course, I am contractually obliged to mention that in 2018, someone applied Bayesian search theory to the case. That is, they started with some simple priors of where he could be and updated against him being on or near the search paths that the searchers took. Here is the posterior superposed on a map of the search area:

And here again is eukaryote’s map, the purple dot marks the place that Ewasko’s body was eventually found:

It took me a little while scrolling back and forth to mentally map the purple dot onto the first image. In case anyone else has the same issue:

What does it mean, fundamentally, when something is NOT where it is most likely to be (like Ewasko’s body here, well outside of the most searched zone)? Or more generally when something—permanently—is NOT the way it is most likely to be? Does it mean our assessment of the likelyhoods was wrong?

Not necessarily; it could mean you’re missing relevant data or that your prior is wrong.

EDIT: @the gears to ascension I meant that it’s not necessarily the case that our assessment of the likelihoods of the data were wrong despite our posterior being surprised by reality.

Thank you for posting this. I’d been following the Bill Ewasko story and Tom Mahood’s blog for years so it’s interesting to see it posted here.

I think the “Death Valley Germans” is another very good series of articles from the same blog, with a much more conclusive (but equally sad) ending.

What strikes me is before 2022 there were a lot of people posting theories, and there was one person who posted to /r/unresolvedmysteries that the discrepency between the reports of whether and how Bill’s truck was parked could be explained by… someone putting it into a U-Haul, taking it away, and then returning it(!). Source: https://ijustdisappear.com/wp/2018/05/22/unsolved-mysteries/

Yeah, if anyone reading this liked this, I also really recommend Mahood’s search for the Death Valley Germans. It’s another kind of brilliant investigation.

Thanks for the link, I hadn’t read that before! Hah, so that guy, KarmaFrog, is the same guy as Adam who posted the videos I recommended. He makes fun of himself in the video about the U-haul thing, which he has now, er, moved away from as a hypothesis.

Ha, I’ll never live the U-Haul down.

To be fair to myself, it was a thought experiment to try to reconcile all the conflicting witness statements and it was the only scenario I could come up with. It was part of a very exhaustive run down of the case that (in another section) also fairly accurately predicted the area Bill might be found and the reasons why he’d be there. To me, you have to go where the evidence takes you and you shouldn’t pre-emptively shut down weird explanations that also happen to fit the facts. But...you shouldn’t buy into them, either (or put them out in public, as I have learned)!

Really appreciate the shout out on this blog, and the commitment to reason and inquiry underlying it.

For the record I’m the same person who brought it up in 2022 on reddit when he was found and objected to it when you posted the original blog to unresolvedmysteries in 2018, so I think this is a case of one particularly annoying person who follows you around chanting “U-Haul! U-Haul!” :)

Thank you for all your hard work on the case, I actually had no idea you were the same Adam on the search and the blog.

I think the U-Haul theory was still a valuable contribution, even though it was debunked thoroughly. It honestly tried to make sense of the facts known at the time. Adam’s contributions to the case were considerable, even though he always insisted on Tom’s contributions being more important.

It’s a real horses / zebra kind of thing, though.

The situation: a hiker goes missing in an area where hikers are known to go missing (and, sadly, die).

The problem: eyewitnesses report the hiker’s truck being in one direction, then not present at all, then in another direction.

Solution 1: eyewitnesses were mistaken about whether they saw the car / what direction it was facing

Solution 2: someone stole the car, took it away for a bit, and then returned it to the trailhead

Occam’s razor requires only one additional assumption for solution 1 (eyewitnesses sometimes/often make mistakes, which is well-known, especially about something as banal about an ordinary car), whereas solution 2 requires us to postulate an entire person (or persons?) who had a motivation to take and then return the car (what? any motivation—e.g. maybe Bill was involved in the drug trade—adds more assumptions).

Let me posit Solution 3: the ranger deliberately recorded his information wrong because he didn’t want to be in trouble for not sounding the alarm about a missing hiker.

or Solution 4: the park management/police colluded together to falsify the witness reports to provide doubt to Bill dying hiking to try and reduce the number of deaths attributable to JTNP

Both Solution 3 and Solution 4 seem far less fanciful than Solution 2. Sure, Solution 5 (“Aliens!”) would be more fantastical than the u-haul one, but just because the Solution 2 doesn’t rely on us changing our understanding of our place in the world doesn’t mean it’s valuable to think about.

If Bill’s body had been discovered buried in the back yard of some drug lord, then sure, Solution 2 all of a sudden looks good. But the situation presented (missing hiker in a place where hikers have been known to get lost and die) does not require that level of attention.

I don’t deny Adam contributed more to the case than almost anyone out there, but the u-haul theory doesn’t become valuable just because it was he who postulated it.

OK, I was gonna stay out of this, but I have to call b.s. (respectfully) on your take.

Solution 1 was indeed always the most likely but I have just as much an issue with the bias towards the unexpected solution as the bias towards the mundane one when the latter does not fit the facts as known.

Your comment is a perfect example of this. Your Solution 3 sounds comfortably mundane except that it’s impossible. The ranger reported his information in real time, not after the fact. Solution 4 is likewise virtually impossible because of the timeline and the number of different agencies involved. So while they sound more plausible on the surface, they have no validity. They just sound less kooky. It contributes even less to understanding the case than the U-Haul. It’s noise.

This is the problem with arranging our thinking solely on the basis of favoring a conventional answer.

At that time we had a situation where Ewasko had not been found anywhere he’d be expected to be found, we had a ping that geographically made no sense (and that was timed suspiciously, though it turned out to be complete coincidence), and we had eyewitnesses (park employees, one of whom was tasked to find the car) who missed his car three times, and the one who said his car was turned around was absolutely adamant on this point. There was also a lot of ancillary evidence for a self-disappearance that again later turned out to be coincidental. But it was there. It wasn’t aliens, and it wasn’t really that much of an evidential reach if you knew as much about the case as I did.

So everyone else, like you, had just handwaved this all away. I had, and still have, a problem with that. So I made the honest attempt to reconcile the eyewitness fact set and put it out there—knowing full well I was going to look like an ass in so doing, even though I said right up front that this was a far-fetched idea, and it comprised about 2% of an exhaustive blog on the case which, may I add, correctly stated in another section where he was most likely to be found.

And yes, it did contribute to the case because it forced people to think of a better scenario which no one had yet done. And someone did—they posited that because of the layout of the parking area, Mimi Gorman had indeed seen (or thought she had seen) the car parked in reverse because of the angle she was viewing it coming back from Keys’ View. Better explanation that didn’t dodge the problem, which I immediately accepted. It would not have happened but for the U-Haul.

I get my back up about this a little because there’s an understandable—but in my opinion intellectually lazy—bias against a non-mundane solution because of the amount of conspiracy theory b.s. on the internet. Look, I get it. Extraordinary claims required extraordinary proof. But this was not a claim. It was simply an idea for discussion and through it, a better idea came out of it which by the way I immediately accepted as more plausible.

Now I could have said “I don’t want to look like a dummy because internet critics will jump all over it despite the years I’ve put into this case seize on this one little thing because it’s an easy smackdown” which was indeed a predictable outcome. And in retrospect I wish I had not put it out there. But at the time, not doing so felt like an act of cowardice. So I put it in the blog, heavily codiciled, and the internet did what it did. I also by the way allowed myself to look like an idiot by pretending I thought foul play was plausible—which I never did—because it’s what the family thought and I didn’t want to add to their pain suggesting Ewasko took off in case I was wrong. And of course, I was.

I think I’ve atoned for my past sins with the videos I’ve put up, which admit to my theoretical mistakes, but as it said, those mistakes built to a full understanding of the case. That’s how scientific inquiry works, and science is full of far-fetched ideas that were ridiculed but later turned out to be right. This was not, of course, one of them. But if they fit the facts I don’t think we should mock those ideas out of existence.

Thank you for your time.

Thanks, you’re right.

Oh whoa, thanks for commenting! I really appreciate your videos and your work on the search.

One aspect of this I find anthropologically interesting is the motivations of Adams and Lahood. Spending years searching for a total stranger’s dead body. Why? Why do we want to “know what happened” so badly? What is at stakes here? There is a movie like that—it’s called The Vanishing. It’s quite good.

It was an interesting puzzle, I like desert hiking, and it was a challenge I needed in my life at that time.

I talk about it a little here (time stamped to the correct location):

Hmm, so is there evidence that he did in fact follow those common-sense guidelines and died in spite of that? Google doesn’t tell me what was found alongside his remains besides a wallet.

I wouldn’t call them “common-sense”. When a modern-day tragedy (death of a child) is required before “hug a tree and survive” becomes a slogan, it seems safe to say that they are counter-intuitive.

If humans did the right thing by default (e.g. “If you are lost, ‘Hug-A-Tree’ and stay put.”), there would be fewer sad stories.

Check out Marsland’s post-coroner’s-report video for all the details, but tentatively it looks like Ewasko:

Hiked alone

Didn’t tell someone the exact trailhead/route he’d be hiking (later costing time, while he was still alive, while rescuers searched other parts of the park)

Didn’t have a GPS unit / PLB, just a regular (non-smart) cellphone (I don’t actually know to what degree a regular smartphone works as a dedicated GPS unit—like, when you’re at the edges of regular coverage, is it doing location stuff from phone + data coverage, or does it have a GPS chip? - but either way, he didn’t have a smartphone)

Had an unclear number of the ten essentials—it seems like a fair number? But (as someone in the youtube comments pointed out) if he had lit a fire, rescuers could have found him from the smoke, so either he didn’t think of that or he just didn’t have a firestarter.

Though I want to point out that doing all of these things—well, it’s not an insane amount of preparation, but it’s above bare minimum common sense / “anyone going out into the woods who thinks at all about safety is already doing this.” I’ve had training in wilderness/outdoor safety type stuff and I’ve definitely done day hikes while less prepared than Ewasko was.

Well, the thing I’m most interested in is the basic compass. From what I can see on the maps, he was going in the opposite direction from the main road for a long time after it should have become obvious that he had been lost. This is a truly essential thing that I’ve never gone into unfamiliar wilderness without.

Ah! I forget about a compass, honestly. He definitely came in with maps (and once he was out there for, like, over eight hours, he would have had cues from the sun.) A lot of the mystery / thing to explain is indeed “why despite being a reasonably competent hiker and map user, Ewasko would have traveled so far in the opposite direction from his car”; defs recommend Adam’s videos because he lays out what seems like a very plausible story there.

(EDIT: was rewatching Adam’s video, yes Bill absolutely had a compass and had probably used it not long before passing, they found one with his backpack near the top. Forgot that.)

Yes, I buy the general theory that he was bamboozled by misleading maps. My claim is that it’s precisely the situation where a compass should’ve been enough to point out that something had gone wrong early enough for the situation to have been salvageable, in a way that sun clues plausibly wouldn’t have.

I think confirmation bias plays a role here. At the point where I think Bill probably went wrong (of course we will never know for sure), there’s a junction of two basically identical jeep trails, neither of which are marked on the park map or most of the then-current trail maps (they are on the topo map). There’s 3 or 4 different ways he might have gone down the wrong road—others have mentioned the two I put out there, there’s a couple of other ways that are possible but less plausible so I didn’t bother with them—but he should have noticed he was going south and not east, by the setting sun. However, because of the angle of the road and the mountain cover, plus having an obvious road to follow, I can see why he wouldn’t have. The sun would still more or less be setting behind him, and to his right, on either route. If he was focused on making time, it’s unlikely he’d note the exact angle of the sun.

My feeling is that because Bill was in a hurry, he did not get out things like a compass or (maybe, depending on how he got lost) more detailed maps until he knew he was lost and by that time he was screwed by the darkness and the topography of the area which wouldn’t allow him to dead reckon back unless he could find the trail again, and at that point it was a wash, of which there are a half dozen in the area. I basically cover this in the video, there’s a lot of information there so it can be hard to follow, but there are reasons why the compass didn’t get him out of the situation.

Thank you for the post, I’ll be watching the video later. The first thought that comes to my mind is why wasn’t there a helicopter search in the area? The paucity of trees on the terrain seems to be perfect for helicopter reconnaissance but I see no mention of that in this post.

Helicopters were used as part of the initial S&R efforts! Also tracking dogs. They just also didn’t find him. There’s a little about it in Tom’s stuff. I don’t know if Tom got the flight path / was able to map where it searched, I think there’s some more info buried in this FOIA’d doc about the initial search that Tom Mahood got ahold of.

(One thing I saw—can’t remember who mentioned this, if it was Mahood or Adam Marsland—is that the FOIA’D doc mentions S&R requesting a helicopter with thermal imaging equipment to come search too, but that doesn’t seem to have actually ever happened. Which is a shame, because at that point Ewasko was alive and presumably closer to/within the main search areas, so that could have actually found him.)

With modern drones, searching in places with as few trees as Joshua tree could be done far more effectively. I don’t know if any parks have trained teams with ~$50k with of drones ready but if they did they could have found him quickly

See also frontier64 and eukaryote on helicopter searches.

The LessWrong Review runs every year to select the posts that have most stood the test of time. This post is not yet eligible for review, but will be at the end of 2025. The top fifty or so posts are featured prominently on the site throughout the year.

Hopefully, the review is better than karma at judging enduring value. If we have accurate prediction markets on the review results, maybe we can have better incentives on LessWrong today. Will this post make the top fifty?