How I Learned To Stop Trusting Prediction Markets and Love the Arbitrage

This is a story about a flawed Manifold market, about how easy it is to buy significant objective-sounding publicity for your preferred politics, and about why I’ve downgraded my respect for all but the largest prediction markets.

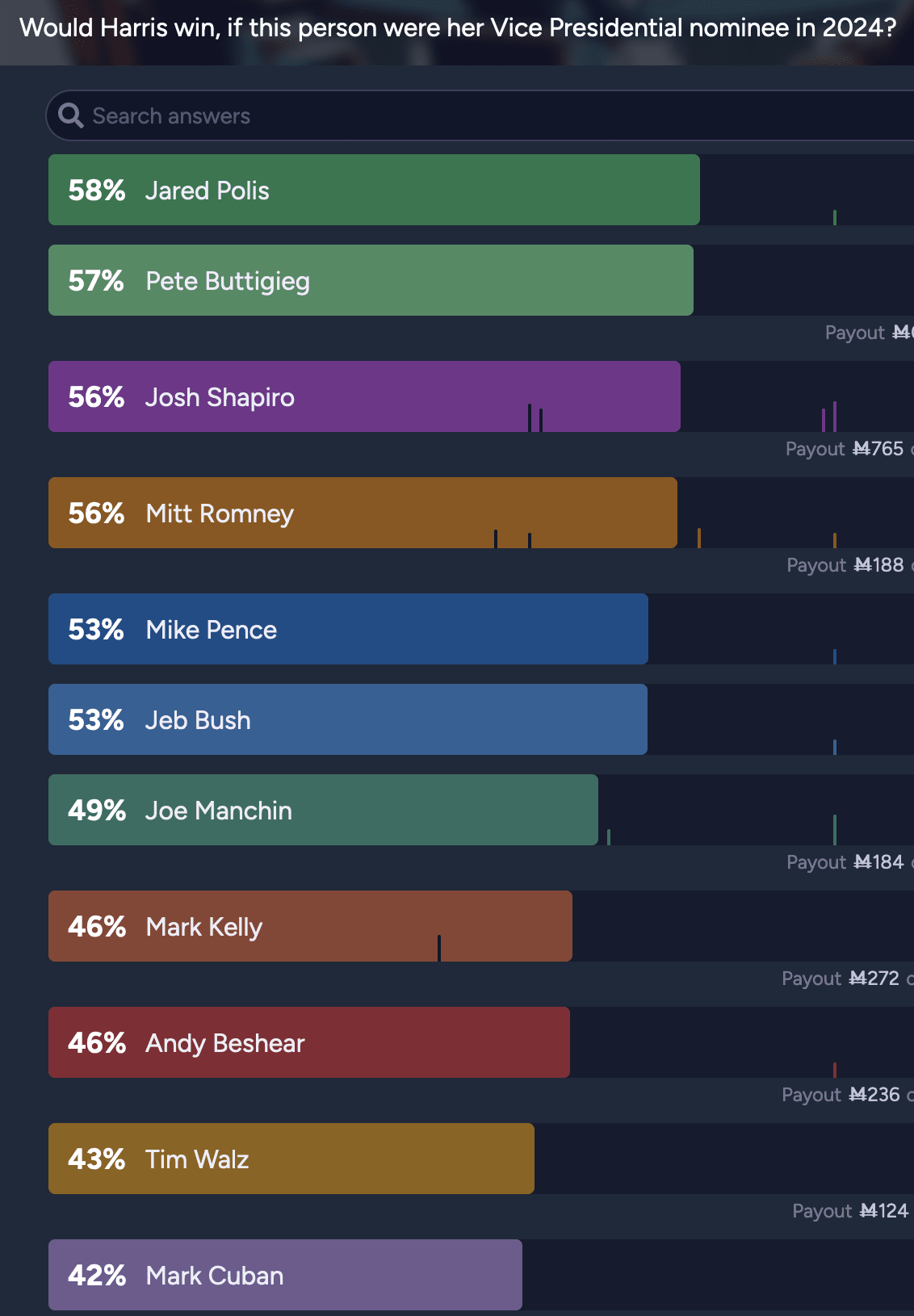

I’ve had a Manifold account for a while, but I didn’t use it much until I saw and became irked by the popularity of this market on the conditional probabilities of a Harris victory, split by VP pick.

The market quickly got cited by prominent rat-adjacent folks on Twitter like Matt Yglesias (who used it to argue that Harris should spend more time courting Never Trumpers), because the question it purports to answer is enormously important.

But as you can infer from the above, it has a major issue that makes it nigh-useless: for a candidate whom you know won’t be chosen, there is literally no way to come out ahead on mana (Manifold keeps its share of the fees when a market resolves N/A), so all but a very few markets are pure popularity contests, dominated by those who don’t mind locking up their mana for a month for a guaranteed 1% loss.

Even for the candidates with a shot of being chosen, the incentives in a conditional market are weaker than those in a non-conditional market because the fees are lost when the market resolves N/A. (Nate Silver wrote a good analysis of why it would be implausible for e.g. Shapiro vs Walz to affect Harris’ odds by 13 percentage points.) So the sharps would have no reason to get involved if even one of the contenders has numbers that are off by a couple points from a sane prior.

You’ll notice that I bet in this market. Out of epistemic cooperativeness as well as annoyance, I spent small amounts of mana on the markets where it was cheap to reset implausible odds closer to Harris’ overall odds of victory. (After larger amounts were poured into some of those markets, I let them ride because taking them out would double the fees I have to pay vs waiting for the N/A.)

A while ago, someone had dumped Gretchen Whitmer down to 38%, but nobody had put much mana into that market, so I spent 140 mana (which can be bought for 14-20 cents if you want to pay for extra play money) to reset her to Harris’ overall odds (44%). When the market resolves N/A, I’ll get all but around 3 mana (less than half a penny) back.

And that half-penny bought Whitmer four paragraphs in the Manifold Politics Substack, citing the market as evidence that she should be considered a viable candidate.

What About Whitmer?

There’s one name in that chart I haven’t mentioned at all: Gretchen Whitmer. The popular governor of Michigan, Whitmer was widely floated as an alternative to Biden and Harris. She said she didn’t want the job, but my read is that’s just something politicians say when they don’t think they’ll get it. So why isn’t she under consideration?

Well, it’s pretty obvious when you look at the other options, isn’t it? Since Harris is a woman of color, the conventional wisdom is that in order to win white swing voters in the Midwest, it’s imperative that she restore “normalcy” to the ticket by picking a white man — or, at the very least, it would confer some advantage. So far, by publicly considering only white men, she hasn’t shown any signs that she disagrees with this philosophy.

Matty Yglesias and Nate Silver do, though (among others). In Yglesias’s words: “Whatever issues Harris faces based on her identity are issues she needs to navigate with her words and actions, regardless. I don’t think conjuring up a white male running mate accomplishes that.”

(At the time of publication, it was still my 140 mana propping her number up; if I sold them, she’d be back under 40%.)

Is this the biggest deal in the world? No. But wow, that’s a cheap price for objective-sounding publicity viewed by some major columnists (including some who’ve heard that prediction markets are good, but aren’t aware of caveats). And it underscores for me that conditional prediction markets should almost never be taken seriously, and indicates that only the most liquid markets in general should ever be cited.

The main effect on me, though, is that I’ve been addicted to Manifold since then, not as an oracle, but as a game. The sheer amount of silly arbitrage (aside from veepstakes, there’s a liquid market on whether Trump will be president on 1/1/26 that people had forgotten about, and it was 10 points higher than current markets on whether Trump will win the election) has kept the mana flowing and has kept me unserious about the prices.

Broke: Prediction markets are an aggregation of opinions, weighted towards informed opinions by smart people, and are therefore a trustworthy forecasting tool on any question.

Woke: Prediction markets are MMOs set in a fantasy world where, if someone is Wrong On The Internet, you can take their lunch money.

Hi! I’m the person that wrote that Manifold newsletter. My opinion: you’re totally right, and it was sloppy to include that as justification that Whitmer was a reasonable choice.

In the counterfactual universe where that conditional market didn’t exist, I might have written that section anyway; it started because I personally believed that a Harris-Whitmer ticket would have about those odds, and it just so happened that the conditional market agreed so I cited it. (In my head it was fine because Whitmer had some chance to be the VP in the past, so the odds couldn’t be totally garbage, but any sense of internal ranking among the contenders was pretty silly.) I’m glad I gave it some disclaimer, but I think it wasn’t a strong enough disclaimer.

As mentioned below, I think conditional markets aren’t always useless; especially those with a >25% chance of occurring and where the correlation-causation issues aren’t too severe. But I’m embarrassed Manifold was promoting this one so much, and I’ll try to fight to make the site more intellectually honest going forward.

Thanks for raising this issue! (…and Whitmer’s probability)

I’m really impressed with your grace in writing this comment (as well as the one you wrote on the market itself), and it makes me feel better about Manifold’s public epistemics.

Isn’t the fact that Manifold is not really a real-money prediction market very important here? If there was real money on the table, for example, it’s less likely that the 1/1/26 market would have been “forgotten”—the original traders would have had money on the line to discipline their attention.

Every time someone calls Manifold (or Metaculus) a “prediction market”, god kills an arbitrageur [even though both platforms are still great!].

Real-money markets do have stronger incentives for sharps to scour for arbitrage, so the 1/1/26 market would have been more likely to be noticed before months had gone by.

However (depending on the fee structure for resolving N/A markets), real-money markets have even stronger incentives for sharps to stay away entirely from spurious conditional markets, since they’d be throwing away cash and not just Internet points. Never ever ever cite out-of-the-money conditional markets.

Even in real-money prediction markets, “how much real money?” is a crucial question for deciding whether to trust the market or not. If you had a tonne of questions and no easy way to find the “forgotten” markets, and each market has (say) 10s-100s of dollars of orders on the book, then the people skilled enough to do the work likely have better ways to turn their time (and capital) into money. For example, I think some of the more niche Betfair markets are probably not worth taking particularly seriously.

Metaculus does not have this problem, since it is not a market and there is no cost to make a prediction. I expect long-shot conditionals on Metaculus to be more meaningful, then, since everyone is incentivized to predict their true beliefs.

The cost to make a prediction is time. The incentive of making it look like “Metaculus thinks X” is still present. The incentive to predict correctly is attenuated to the extent that it’s a long-shot conditional or a far future prediction. So Metaculus can still have the same class of problem.

The reasoning you gave sounds sensible, but it doesn’t comport with observations. Only questions with a small number of predictors (e.g. n<10) appear to have significant problems with misaligned incentives, and even then, those issues come up a small minority of the time.

I believe that is because the culture on Metaculus of predicting one’s true beliefs tends to override any other incentives downstream of being interested enough in the concept to have an opinion.

Time can be a factor, but not as much for long-shot conditionals or long time horizon questions. The time investment to predict on a question you don’t expect to update regularly can be on the order of 1 minute.

Some forecasters aim to maximize baseline score, and some aim to maximize peer score. That influences each forecaster’s decision to predict or not, but it doesn’t seem to have a significant impact on the aggregate. Maximizing peer score incentivizes forecasters to stay away from questions where they are strongly in agreement with the community. (That choice doesn’t affect the community prediction in those cases.) Maximizing baseline score incentives forecasters to stay away from questions on which they would predict with high uncertainty, which slightly selects for people who at least believe they have some insight.

Questions that would resolve in 100 years or only if something crazy happens have essentially no relationship with scoring, so with no external incentives in any direction, people do what they want on those questions, which is almost always to predict their true beliefs.

I don’t think we disagree on culture. I was specifically disagreeing with the claim that Metaculus doesn’t have this problem “because it is not a market and there is no cost to make a prediction”. Your point that culture can override or complement incentives is well made.

The title “How I Learned To Stop Trusting Prediction Markets and Love the Arbitrage” isn’t appropriate for the content of the post. That there is a play-money prediction market in which it costs very little to make the prices on conditional questions very wrong does not provide significant reasons to trust prediction markets less. That this post got 193 karma leading me to see it 2 months later is a sign of bad-voting IMO. (There are many far better, more important posts that get far less karma.)

In conditional prediction markets with exclusive conditionals, it should be possible to let people invest $N and then have $N to trade with in each of the markets.

(I think Manifold considered adding this functionality at some point.)

Sorry for the self promotion, but some folks may find this post relevant: https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/uDXRxF9tGqGX5bGT4/logical-share-splitting (ctl-F for “Application: Conditional prediction markets”)

tldr: Gives a general framework that would allow people to make this kind of trade with only $N in capital, just as a natural consequence of the trading rules of the market.

Anyway, I definitely agree that Manifold should add the feature you describe! (As for general logical share splitting, well, it would be nice, but probably far too much work to convert the existing codebase over.)

I made that market. Some thoughts

1.Seems kind of inaccurate to not put in Matt’s tweet particularly if you’re gonna call it “objective sounding”.

Matt himself calls says “seriously but not literally”. So he agrees with you, I think.

2.Regarding fees on conditional markets, I don’t know.

3.

I don’t know that this is as big a problem as it seems. A popularity contest where it costs something to vote is a better kind than we usually see. Overall I agree that conditional markets aren’t to be taken too seriously. But I think the tone of this is probably too negative to this audience. This one went fine.

4.

Thanks. I did the same. Overall I thought the markets seemed to say pretty sensible things.

Thanks—I didn’t recall the content of Yglesias’ tweet, and I’d noped out of sorting through his long feed. I suspect Yglesias didn’t understand why the numbers were weird, though, and people who read his tweet were even less likely to get it. And most significantly, he tries to draw a conclusion from a spurious fact!

Allowing explicitly conditional markets with a different fee structure (ideally, all fees refunded on the counterfactual markets) could be an interesting public service on Manifold’s part.

The only part of my tone that worries me in retrospect is that I should have done more to indicate that you personally were trying to do a good thing, and I’m criticizing the deference to conditional markets rather than criticizing your actions. I’ll see if I can edit the post to improve on that axis.

I think we still differ on that. Even though the numbers for the main contenders were just a few points apart, there was massive jockeying to put certain candidates at the top end of that range, because relative position is what viewers noticed.

I think the post moved me in your direction, so I think it was fine.

I learned this lesson looking at the conditional probabilities of candidates winning given they were nominated in 2016, where the candidates with less than about 10% chance of being the nominee had conditional probabilities with noise between 0 and 100%. And this was on the thickly traded real-money markets of Betfair! I personally engage in, and also recommend, just kinda throwing out any conditional probabilities that look like this, unless you have some reason to believe it’s not just noise.

Another place this causes problems is in the infinitely-useful-if-they-could-possibly-work decision markets, where you want to be able to evaluate counterfactual decisions, except these are counterfactuals so you don’t make the decision so there’s no liquidity and it can take any value.

These problems seem less acute if you instead break apart conditionals into a base question and a conjunctive market (like this one for the Democratic VP question), where you don’t have the possibility of a N/A resolution blowing a hole in the pricing.

Yes, and I gained some easy mana from such markets; but the market that got the most attention by far was the intrinsically flawed conditional market.

But now you have the new problem that most of the probabilities in the conjunctive market are so close to the risk free interest rate that it’s hard to get signal out of them.

For example, suppose I believed that Mark Kelly would be a terrible pick and cut Harris’s chances in half, and I conclude that therefore his price on the conjunctive market should be 2% rather than 4%. Buying NO shares for 96 cents on a market that lasts for several months is not an attractive proposition when I could be investing mana elsewhere for better returns, so I won’t bother and the market won’t incorporate my opinion.

Also, I believe prices on Manifold can only be whole number percents, which is another obstacle to getting sane conditional probabilities out of conjunctive markets.

I agree, these conditionals are pretty sensitive to small inefficiencies in pricing when the probability is low. It does suck. Perhaps one day we will have markets denominated in appreciating assets, so you can be exposed to general growth while you’re also exposed to your bet on the market.

Fortunately that’s not true, though it does seem to only display one decimal place below the integer percent.

Could you make it more clear how you would change the original Harris market to avoid the problem? I’m not sure what exactly you mean by “base question and a conjunctive market”. I figure you’re talking about the “other” option in the market you link, which prevents N/A. But how do you add that to the Harris market? Is it just adding one more option “Another person not listed here is nominee and Harris wins”?

Happy to clarify.

Similar to what Ben said, you work out the conditional probabilities from other markets.

First, here’s a fact about probabilities that you’ll need to use: the probability of “A conditional on B” (for example, “Harris wins conditional on choosing Walz as her VP”) is equal to probability of “A and B” ÷ probability of “B” (so, “The Harris-Walz ticket wins” ÷ “Walz is the VP”) .

So whenever you want to know P(A|B) (the probability of “A conditional on B”), you can instead ask P(A&B) (probability of “A and B”) and P(B).

That’s what the linked market (more-or-less) does. It asks “who will be the next US VP?”. This is basically asking “if the presidential candidate picks this person as the VP, will their ticket win?”. You can divide this by the probability “will the relevant presidential candidate pick this person as VP”, to get the conditional probability you want.

My guess is that you just don’t have any conditionals, but work them out from other markets.

Eg. One market on “Harris wins with X on the ticket”, one on “Harris looses with X on the ticket”, “Harris chooses X for VP” and so on. Then the chances of her winning, conditional on different candidates, can be worked out by comparing how these markets are doing.

I think the solution to this particular problem is to report the liquidity of conditional markets weighted by the probability of the condition being satisfied, and for people to only care about high liquidity markets.

I read your post but didn’t understand it immediately. After thinking about it, I wrote what I feel the main points are in my own words. Maybe this makes it more clear to others too. Or maybe the OP will comment that I misunderstood something.

The “Harris market” can be seen as (is functionally equivalent to) a collection of markets. Each market has the following form:

Each market resolves as follows:

Yes, if {person} is the nominee and Harris wins.

No, if {person} is the nominee and Harris loses.

N/A, if {person} not the nominee.

Each market is independent. I mean this in the sense that there is no manifold mechanic that ties them together, except that they are visually grouped under “the Harris market”.

There is a problem with this kind of market. When people see a high probability of a person in the market, they mistake it as meaning that the person is a likely choice or a good choice.

This is a mistake because it does not follow from the market’s incentives. Imagine someone that will obviously not be nominee, like “Batman”. You know that Batman will not be nominee, so you know that this market will resolve to N/A. This makes bets on Batman meaningless. You can bet Yes or No, it doesn’t matter. The market will resolve to N/A and you get your money back. Some people do this because they find it fun to see that Batman has a high Yes probability.

Batman can’t be nominee because he doesn’t exist, but you have the same problem for obviously terrible candidates. Imagine the person most hated by all potential Harris voters, “the Joker”. (Assume Joker was a real person.) The true probability of Harris winning with Joker is tiny. Yet, in the market, there is little incentive to correctly predict this. Everyone knows Joker is a terrible choice, so Harris is not going to choose him as nominee, so the market will resolve N/A.

The author of the Substack you quote makes this mistake. They did not consider what the market incentivizes.

They also made a separate mistake that applies to all prediction markets, not just misleading conditional markets. They did not take into account how much money it takes to intentionally influence the market. It is easy (cheap) for people to push small markets (markets with little money invested) in their desired direction.

This conclusion seems too strong. For almost all of those options the probability of resolving N/A was very high, so the incentive to correct the price was low. That’s not true of many conditional markets, like “If Republicans/Democrats win the presidency, will border crossings be above [number]”, and then the probability of resolving N/A is more like 50% and the incentive to correct prices remains. Does that really justify “almost never” taking conditional markets seriously? Same for “only the most liquid markets” “should ever be cited”—the market I think you said that people had forgotten about only had about 22 traders when it was at 60%, which isn’t a lot. I don’t see why this means markets that aren’t the most liquid but have 500 traders, or markets on polymarket that have ten thousand $ in volume (small for polymarket) should not ever be cited. Manifold markets do have problems with accuracy but it’s not that bad.

Yes 50% chance of N/A would add a ‘couple points’ of noise, but that doesn’t make the market useless if it shows a larger difference. In the market you took a screenshot of Shapiro appears to have been at a reasonable 46% for most of the market’s existence.

Conditional prediction markets could resolve to the available options weighted by calibration on similar subjects of the holders in unconditional markets, rather than N/A. Such markets might end up looking like predicting what well-calibrated people will pick, or following on after they bet (implying not expecting significant well-calibrated disagreement). Well-calibrated people could then expect to earn a profit by betting in conditional markets if they bet closer to the consensus than the market does, partly weighted in their favor for being better calibrated relative to the whole market.

The LessWrong Review runs every year to select the posts that have most stood the test of time. This post is not yet eligible for review, but will be at the end of 2025. The top fifty or so posts are featured prominently on the site throughout the year.

Hopefully, the review is better than karma at judging enduring value. If we have accurate prediction markets on the review results, maybe we can have better incentives on LessWrong today. Will this post make the top fifty?

This is weirdly meta.