Helpful background reading: What’s the deal with prions?

A novel lethal infectious neurological disease emerged in American deer a few decades ago. Since then, it’s spread rapidly across the continent. In areas where the disease is found, it can be very common in the deer there.

Chronic wasting disease isn’t caused by a bacteria, virus, protist, or worm – it’s a prion, which is a little misshapen version of a protein that occurs naturally in the nervous systems of deer.

Chemically, the prion is made of exactly the same stuff as its regular counterpart – it’s a string of the same amino acids in the same order, just shaped a little differently. Both the prion and its regular version (PrP) are monomers, single units that naturally stack on top of each other or very similar proteins. The prion’s trick is that as other PrP moves to stack atop it, the prion reshapes them – just a little – so that they also become prions. These chains of prions are quite stable, and, over time, they form long, persistent clusters in the tissue of their victims.

We know of only a few prion diseases in humans. They’re caused by random chance misfolds, a genetic predisposition for PrP to misfold into a prion, accidental cross-contamination via medical supplies, or, rarely, from the consumption of prion-infected meat. Every known animal prions is a misfold of the same specific protein, PrP. PrP is expressed in the nervous system, particularly in the brain – so infections cause neurological symptoms and physical changes to the structure of the brain. Prion diseases are slow to develop (up to decades), incurable, and always fatal.

There are two known infectious prion diseases in people. One is kuru, which caused an epidemic among tribes who practiced funerary cannibalism in Papua New Guinea. The other is mad cow disease, also known as bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) AKA Variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, which was first seen in humans in 1996 in the UK, and comes from cows.

Chronic wasting disease (CWD)…

Is, like every other animal prion disease, a misfold of PrP. PrP is quite similar in both humans and deer.

Is found in multiple deer species which are commonly eaten by humans.

Can be carried in deer asymptomatically.

But it doesn’t seem to infect people. Is it ever going to? If a newly-emerged virus were sweeping across the US and killing deer, which could be spread through consuming infected meat, I would think “oh NO.” I’d need to see very good evidence to stop sounding the alarm.

Now, the fact that it’s been a few decades, and it hasn’t spread to humans yet, is definitely some kind of evidence about safety. But are we humans basically safe from it, or are we living on borrowed time? If you live in an area where CWD has been detected, should you eat the deer?

Sidenote: Usually, you’ll see “BSE” used for the disease in cows and “VCJ” for the disease in humans. But they’re caused by the same agent and this essay is operating under a zoonotic One Health kind of stance, so I’m just calling the disease BSE here. (As well as the prion that causes it, when I can get away with it.)

In short

The current version of CWD is not infectious to people. We checked. BSE showed that prions can spill over, and there’s no reason a new CWD variant will never do the same. The more cases there are, the more likely it is to spill over. That said, BSE did not spill over very effectively. It was always incredibly rare in humans. It’s an awful disease to get, but the chance of getting it is tiny. Prions in general have a harder time spilling over between species than viruses do. CWD might behave somewhat differently but probably will stay hampered by the species barrier.

Why do I think all of this? Keep reading.

Prions aren’t viruses

I said before that if a fatal neurological virus were infecting deer across the US, and showed up in cooked infected meat, my default assumption would be “we’re in danger.” But a prion isn’t a virus. Why does that matter?

Let’s look at how they replicate. A virus is a little bit of genetic material in a protein coating. You, a human, are a lot of genetic in a protein coating. When a virus replicates, it slips into your cells, and it hijacks your replication machinery to run its genes instead. Instead of all the useful-to-you tasks your genome has planned, the virus’s genome outlines its own replication, assembles a bunch more viruses, and blows up the factory (cell) to turn them loose into the world.

In other words, the virus using a robust information-handling system that both you and it have in common – the DNA → RNA → protein pipeline often called “the central dogma” of biology. To a first approximation, you can just add any genetic information at all into the viral genome, and as long as it doesn’t interfere with the virus’s process, whatever you add will get replicated in there too.

Prions do not work like this. They don’t tap into the central dogma. What makes them so fundamentally cool is that they replicate without touching the replication machinery that everything else alive uses – their replication is structural, like a snowflake forming. The host provides raw material in the form of PrP, and the prion – once it lands – encourages that material to shape in the right way for more to form atop it.

What this means is that you can’t encode arbitrary information into a prion. This isn’t just a factor – it’s not as though a prion runs on a separate “protein genome” we could decipher and then encode what we like into. The entire structure of the prion has to work together to replicate itself. If you made a prion with some different fold in it, that fold has to not just form a stable protein, but to pass itself along as well. They don’t have a handy DNA replicase enzyme to outsource to – they have to solve the problem of replication themselves, every time.

Prions can evolve, but they do it less – they have fewer free options, they’re more constrained than a virus would be in terms of changes that don’t interrupt the rest of the refolding process and that on top of that promulgate themselves.

This means that prions are slower to evolve than viruses. …I’m pretty sure, at least. It makes a lot of sense to me. The thing that this definitely means is that:

It’s very hard for prions to cross species barriers

PrP is a very conserved protein across mammals, meaning that all mammals have a version of PrP that’s pretty similar – 90%+ similarity.[1] But the devil lies in that 10%.

Prions are finely tuned – to convert PrP to a prion, it basically needs to be identical, or at least functionally identical, everywhere the prion works. It not just needs to be susceptible to the prion’s misfolding, it also needs to fold into something that itself can replicate. A few amino acid differences can throw a wrench in the works.

It’s clear that infectious prions can have a hard time crossing species barriers. It depends on the strain. For instance: Mouse prions convert hamster PrP.[2] Hamster prions don’t convert mouse PrP. Usually a prion strain converts its usual host PrP best, but one cat prion more efficiently converts cow PrP. In a test tube, CWD can convert human or cow PrP a little, but shows slightly more action with sheep PrP (and much more with, of course, deer PrP.)

This sounds terribly arbitrary. But remember, prion behavior comes down to shape. Imagine you’re playing with legos and duplo blocks. You can stack legos on legos and duplos on duplos. You can also put a duplo on top of a lego block. But then you can only add duplo blocks on top of that – you’ve permanently changed what can get added to that stack.

When we look at people – or deer, or sheep, etc – who are genetically resistant to prions (more on that later), we find that serious resistance can be conferred by single nucleic acid changes in the PrP gene. Tweak one single letter of DNA in the right place, and their PrP just doesn’t bend into the prion shape easily. If the infection takes, it proceeds slower – slow enough a person might die of old age before the prion would kill them.

So if a decent number of members of a species can be resistant to prion diseases, based on as little as one amino acid – then a new species, one that might have dozens of different amino acids in the PrP gene, is unlikely to be fertile ground for an old prion.

But prions do cross species barriers

Probably the best counterargument to everything above is that another prion disease, BSE, did cross the species barrier. This prion pulled off a balancing act: it successfully infected cows and humans at the same time.

Let’s be clear about one big and interesting thing: BSE is not good at crossing the species barrier. When I say this, I mean two things:

First, people did not get it often. While the big UK outbreak was famously terrifying, only around 200 people ever got sick from mad cow disease. Around 200,000 cows tested positive for it. But most cows weren’t tested. Researchers estimate that 2 million cows total in the UK had BSE, most of which were slaughtered and entered the food chain. These days, Britain has 2 million cows at any given time.

At first glance, and to a first approximation, I think everyone living in the UK for a while between 1985 and 1996 or so (who ate beef sometimes) must have eaten beef from an infected animal. That’s approximately who the recently-overturned blood donation ban in the US affected. I had thought that was sort of an average over who was at risk of exposure – but no, that basically encompassed everyone who was exposed. Exposure rarely leads to infection.

You’re more likely to get struck by lightning than to get BSE even if you have eaten BSE-infected beef.

Second, in the rare cases the disease takes, it’s slower. Farm cows live short lives, and the cows that died from BSE would have gotten old for the beef industry at 4-5 years post-exposure. They survived at most weeks or months after symptoms began. Humans infected with BSE, meanwhile, can harbor it for up to decades post-exposure, and live an average of over a year after showing symptoms.

I think both of these are directly attributable to the prion just being less efficient at converting human PrP – versus the PrP of the cows it was adapted to. It doesn’t often catch on in the brain. When it does, it moves extremely slowly.

But it did cross over. And as far as I can tell, there’s no reason CWD can’t do the same. Like viruses, CWD has been observed to evolve as it bounces between hosts with different genotypes. Some variants of CWD seem more capable of converting mouse PrP than the common ones. The good old friend of those who play god, serial passaging, encourages it.

(Note also that all of the above differs from kuru, which did cause a proper epidemic. Kuru spread between humans and was adapted for spreading in humans. When looking to CWD, BSE is a better reference point because it spread between cows and only incidentally jumped to humans – it was never adapted for human spread.)

How is CWD different from BSE?

BSE appears in very low, very low numbers anywhere outside the brains and spines of its victims. CWD is also concentrated in the brains, but also appears in the spines and lymphatic tissue, and to a lesser but still-present degree, everywhere else: muscle, antler velvet, feces, blood, saliva. It’s more systematic than BSE.

Cows are concentrated in farms, and so are some deer, but wild deer carry CWD all hither and yon. As they do, they leave it behind in:

Feces – Infected deer shed prions in their feces. An animal that eats an infected deer might also shed prions in its feces.

Bodies – Deer aren’t strictly herbivorous if push comes to shove. If a deer dies, another deer might eat the body. One study found that after a population of reindeer started regularly gnawing on each other’s antlers (#JustDeerThings), CWD swept in.

Dirt – Prions are resilient and can linger, viable, in soil. Deer eat dirt accidentally while eating grass, as well as on purpose from time to time and can be infected.

Grass – Prions in the soil or otherwise deposited onto plant tissue can hang out in living grass for a long time.

Ticks – One study found that ticks fed CWD prions don’t degrade the protein. If they’re then eaten by deer (for instance, during grooming), they could spread CWD. This study isn’t perfect evidence; the authors note that they fed the ticks a concentration of prions about 1000x higher than is found in infected deer blood. But if my understanding of statistics and infection dynamics is correct, that suggests that maybe 1 in 1000 ticks feeding on infected deer blood reaches that level of infectivity? Deer have a lot of ticks! Still pretty bad!

That’s a lot of widespread potentially-infectious material.

When CWD is in an area, it can be very common – up to 30% of wild deer, and up to 90% of deer on an infected farm. These deer can carry CWD and have it in their tissues for quite some time asymptomatically – so while it frequently has very visible behavioral and physical symptoms, it also sometimes doesn’t.

In short, there’s a lot of CWD in lots of places through the environment. It’s also spreading very rapidly. If a variant capable of infecting both deer and humans emerged, there would be a lot of chances for possible exposure.

What to do?

As an individual

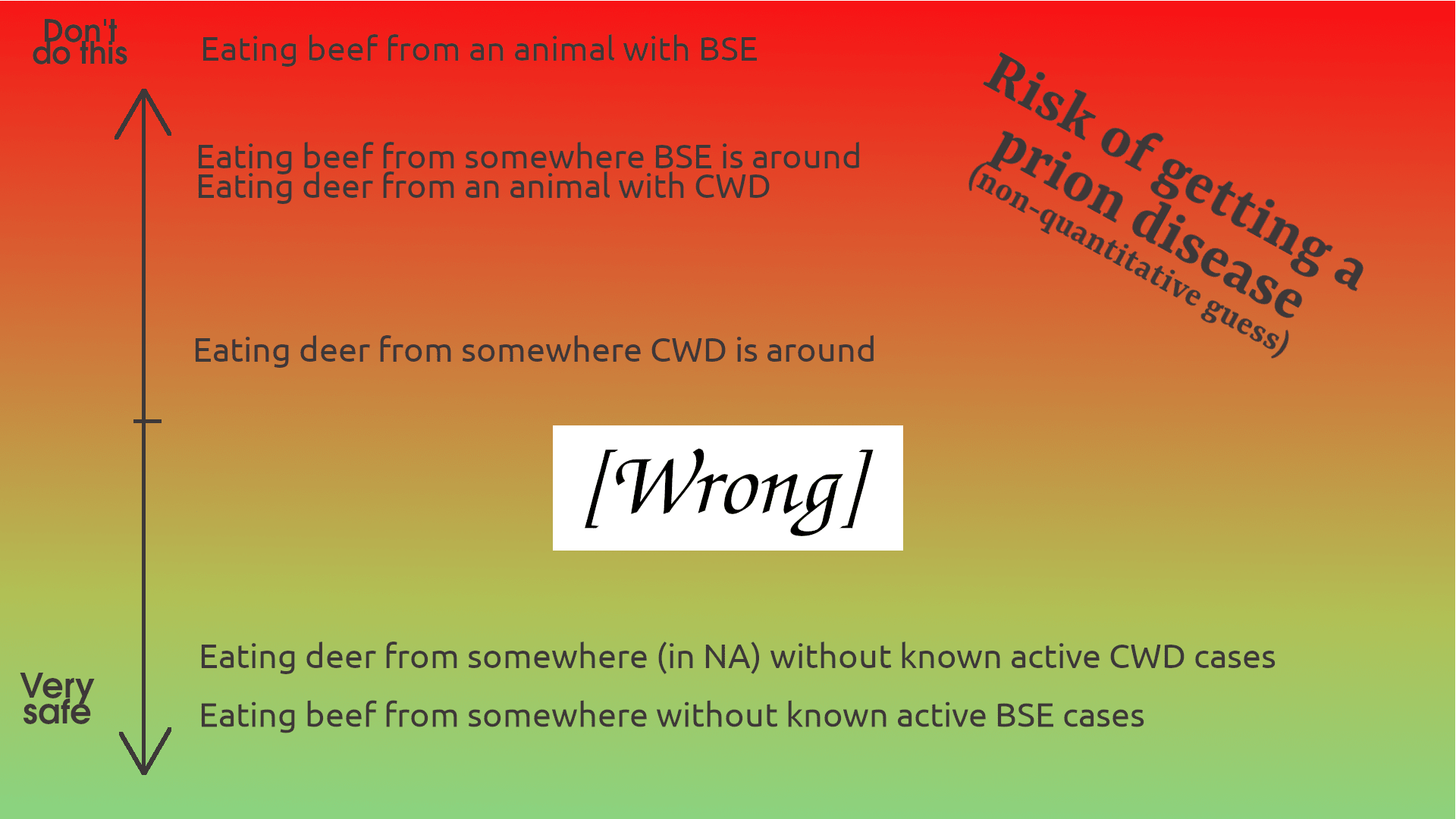

As with any circumstance at all, COVID or salmonella or just living in a world that is sometimes out to get you, you have to choose what level of risk you’re alright with. At first, writing this piece, I was going to make a suggestion like “definitely avoid eating deer from areas that have CWD just in case your deer is the one that has a human-transmissible prion disease.” I made a little chart about my sense of the relative risk levels, to help put the risk in scale even though it wasn’t quantified. It went like this:

But, as usual, quantification turns out to be pretty important. I actually did the numbers about how many people ever got sick from BSE (~200) and how many BSE-infected cows were in the food chain (~2,000,000), which made the actual risk clear. So I guess the more prosaic version looks like this:

...This is sort of a joke, to be clear. There’s not a health agency anywhere on earth that will advise you to eat meat from cows known to have BSE, and the CDC recommends not eating meat from deer that test positive for CWD (though it’s never infected a human before.)

On top of that, the overall threat is still uncertain because what you’re betting on is “the chance that this animal will have had an as-of-yet undetected CWD variant that can infect humans.” There’s inherently no baseline for that!

We don’t know what CWD would act like if it spilled over. It might be more infectious and dangerous than other infectious prion diseases we’ve seen – remember, with humans, the sample size is 2! So if CWD is in your area and it’s not a hardship to avoid eating deer, you might want to steer clear. …But the odds are in your favor.

As a society

There’s not an obvious solution. The epidemic spreading among deer isn’t caused by a political problem, it’s from nature.

The US is doing a lot right: mainly, it is monitoring and tracking the spread of the disease. It’s spreading the word. (If nothing else, you can keep track of this by subscribing to google alerts for “chronic wasting disease”, and then pretty often you’ll get an email saying things like “CWD found in Florida for the first time” or “CWD found an hour from you for the first time.”) It is encouraging people to submit deer heads for testing, and not to eat meat from deer that test positive. The CDC, APHIS, Fish & Wildlife Service, and more are all aware of the problem and participating in tracking it.

What more could be done? Well, a lot of the things that would help a potential spillover of CWD look like actions that can be taken in advance of any threatening novel disease. There is research being done on prions and how they cause disease, better diagnostics, and possible therapeutics. All of these are important. Prion disease diagnosis and treatment is inherently difficult, and on top of that, has little overlap with most kinds of diagnosis or treatment. It’s also such a rare set of diseases that it’s not terribly well studied. (My understanding is that right now there are various kinds of tests for specific prion diseases – which could be adapted for a new prion disease – that are extremely sensitive although not particularly cheap or widespread.)

I don’t know a lot about the regulatory or surveillance situation vis-a-vis deer farms, or for that matter, much about deer farms at all. I do know that they seem to be associated with outbreaks, and heavy disease prevalence once there is an outbreak. That’s a smart area to an eye on.

If CWD did spill over, what would happens?

It will probably also take time to locate cases and identify the culprit, but given the aforementioned awareness and surveillance of the issue, it ought to take way less time than it took to identify the causative agent of BSE. Officials are already paying attention to deaths that could potentially be CWD-related, like neurodegenerative illnesses that kill young people.

First, everyone gets very nervous about eating venison for a while.

After that, I expect the effects will look a lot like the aftermath of mad cow disease. Mad cow disease, and very likely a hypothetical CWD spillover, would not be transmissible between people in usual ways – coughing, skin contact, fomites, whatever.

It is transmissible via unnatural routes, which is to say, blood transfusions. You might remember how people who’d spent over 6 months in Britain couldn’t donate blood in the US until 2022, a direct response to the BSE outbreak. Yes, the disease was extremely rare, but unless you can quickly and cheaply test incoming blood donations, a donor could donate blood to multiple people. Suppose some of them donate blood down the line. You’d have a chain of infection and a disease with a potentially decades-long incubation period. And remember, the disease is incurable and fatal. So basically, the blood donation system (and probably other organ donation) becomes very problematic.

That said, I don’t think it would break down completely. In the BSE case, lots of people in the UK eat beef from time to time – probably most people. But with a deerborne disease, I would guess that a lot of the US population could confidently declare that they haven’t eaten deer within the past, say, year or so (prior to a detected outbreak.) So I think there’d be panic and perhaps strain on the system but not necessarily a complete breakdown. Again, all of this is predicated on a new prion disease working like known human prion diseases.

Genetic resistance

One final fun fact: People who have a certain allele in the PrP gene – specifically, have the genotype PRNP 129M/V or V/V – are incredibly genetically resistant to known infectious prion diseases. If they do get infected, they survive for much longer.

It’s also not clear that this would hold true for a hypothetical CWD crossover to humans. But it is true for both kuru and BSE. It’s also partly (although not totally) protective against sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease.

If you’ve gotten a service like 23&me, maybe check out your data and see if you’re resistant to infectious prion diseases. Here’s what you’re looking for:

129M/V or V/V (amino acids), or G/G or A/G (nucleotides) – rs1799990

If you instead have M/M (amino acids) or A/A (nucleotides) at that site, you’re SOL at a higher but still very low overall risk.

Final thoughts

I think exercises like “if XYZ disease emerges, what will the ramifications and response be” are valuable. They lead to questions like “what problems will seem obvious in retrospect” and “how can we build systems now that will improve outcomes of disasters.” This is an interesting case study and I might revisit it later.

Has anyone reading this ever been struck by lightning? That’s the go-to comparison for things being rare. But 1 in 15,000 isn’t, like, unthinkably rare. I’m just curious.

No, seriously, what’s the deal with deer farms? I never think about deer farms much. When I think of venison, I imagine someone wearing camo and carrying a rifle out into a national forest or a buddy’s backyard or something. How many deer are harvest from hunting vs. farms? What about in the US vs. worldwide? Does anyone know? Tell me in the comments.

If you want to encourage my work, check out my Patreon. Today’s my birthday! I sure would appreciate your support.

Also, this eukaryote is job-hunting. If you have or know of a full-time position for a researcher, analyst, and communicator with a Master’s in Biodefense, let me know:

Eukaryote Writes Blog (at) gmail (dot) com

In the mean time, perhaps you have other desires. You’d like a one-off research project, or there’s a burning question you’d love a well-cited answer to. Maybe you want someone to fact-check or punch up your work. Either way, you’d like to buy a few hours of my time. Well, I have hours, and the getting is good. Hit me up! Let’s chat. 🐟

- ^

This is kind of weird given that we don’t know what PrP actually does – the name PrP just stands “prion protein” because it’s the protein that’s associated with prions, and we don’t know its function. We can genetically alter mice so that they don’t produce PrP at all, and they show slight cognitive issues but they’re basically fine. Classic evolution. It’s appendices all over again.

- ^

Sidebar: When we look at studies for this, we see that like a lot of pathology research, there’s a spectrum of experiments on different points on the axis from “deeply unrealistic” to “a pretty reasonable simulacrum of natural infection”, like:

1. Shaking up loose prions and PrP in a petri dish and seeing if the PrP converts

2. Intracranial injection with brain matter (i.e. grinding up a diseased brain and injecting some of that nasty juice into the brain of a healthy animal and seeing if it gets sick)

3. Feeding (or some other natural route of exposure) a plausible natural dose of prions to a healthy animal and seeing if that animal gets sick

The experiments mentioned below are based on 1. Only experiments that do 3 actually prove the disease is naturally infectious. For instance, Alzheimer’s disease is “infectious” if you do 2, but since nobody does that, it’s not actually a contagious threat. That said, doing more-abstracted experiments means you can really zoom in on what makes strain specificity tick.

FYI, structural conformation diseases are actually quite common in humans, we just call them something different: amyloidoses. For example, TTR amyloidosis kills a good fraction of our oldest humans.

From https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2634591:

“Prions were originally defined as a unique class of infectious agents, whose infectivity relates solely to protein. In mammals, they cause fatal neurodegenerative diseases, such as Creutzfeldt-Jacob disease of man, sheep scrapie and bovine spongiform encephalopathy (reviewed in refs. 1 and 2). All these diseases are related to the PrP protein, whose conformationally altered form (PrPSc) is able to convert the normal host-encoded protein (PrPC) into this altered prion form. While only one prion protein is known in mammals, the prions appear to represent just a part of a much wider phenomenon, amyloidoses.

Amyloid diseases represent a group of more than 30 human diseases, which are characterized by deposition in different tissues of fibrous aggregates of conformationally altered proteins.”

The thing that makes prion diseases scary is that they’re potentially transmissible; but the reality is that even if you never catch a prion disease, a protein aggregation disease will eventually kill you if you live long enough.

There’s a formatting issue with the link, should be: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2634591/

In particular, Alzheimer’s disease is a dual prion disease (amyloid-β and tau), and there are numerous other known prion diseases.

See Nguyen et al (2021). Amyloid Oligomers: A Joint Experimental/Computational Perspective on Alzheimer’s Disease, Parkinson’s Disease, Type II Diabetes, and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and Shi et al (2021). Structure-based classification of tauopathies for some great detail on this.

There is a lot of drug development based on that theory and most of it came up empty and the one that didn’t came up empty was Abuhelm which is widely seen as one of the worst FDA drug approvals of recent years.

There are actually three amyloid antibodies that have shown some success: aducanumab (Aduhelm), lecanemab (Leqembi), and donanemab. I think the FDA approval of aducanumab was absolutely the right decision, though it’s far from a miracle drug.

I spent about six months of my life buried in the Alzheimer literature. There’s a mountain of evidence for this hypothesis. Take a look at my previous comments if you’re curious.

Regarding why deer are farmed in the US: in some places, deer are farmed for consumption, but will typically be non-native deer, considering most states forbid the sale of meat from native species, and thus other cervids than the WTD. (This goes back a bit to controlling depopulation triggered by hunting for the market.)

Most farming of deer in the continental US is actually for white tail deer, and specifically to develop and grow mutant genetic stocks that “score” very well based on antler size/complexity. A reindeer, for example, might bring a few hundred dollars in-market for meet, but someone will pay $20K+ for a Boone & Crockett scoring white tail to hang on their wall as a trophy. So, they farm the deer to sell examples with highly-prized genetics to ranches, who then charge people to shoot them.

This is, needless to say, exceptionally controversial in the hunting community, and many of these deer are not even allowed for ranking by the major groups like B&C.

There’s the problem of the fat tail—CWD is insanely good at spreading, with constant shedding of prions by the infected. Deer with CWD can very effectively spread the disease through their saliva and mucus, whereas BSE requires cannibalism of neural tissues. Probably nothing major happens and it doesn’t cross over to humans. But what happens if it does?

Consider what happens if a disease as infectous, deadly, with long incubation times as CWD crosses over to humans. What if the incubation time is 10 years in humans? That would be enough time to infect every human on Earth (I don’t think that would kill everyone due to genetic differences).

This is a major point that the author does not address. The author assumes that CWD risk is low because BSE risk was low. But there is a huge difference between BSE and CWD that is mentioned in this very article: BSE is largely restricted to neural tissues, whereas CWD is in basically all tissues and bodily fluids. The BSE infectivity numbers would only apply to a disease that is restricted to tissues that are generally not consumed

Future readers of this blog post may be interested in this book-review entry at ACX, which is much more suspicious/wary/pessimistic about prion disease generally:

They dispute the idea that having M/V or V/V genes reduces the odds of getting CJD / mad cow disease / etc.

They imply that Britain’s mad cow disease problem maybe never really went away, in the sense that “spontaneous” cases of CJD have quadrupled since the 80s, so it seems CJD is being passed around somehow?

https://www.astralcodexten.com/p/your-book-review-the-family-that

Nit: your “Duplo” diagram shows a ratio of 1:3 which would make it a (hypothetical!) Triplo. Real Duplos are 1:2, and (discontinued) Quatro are 1:4 with Lego and 1:2 with Duplo.

(This is all in each dimension, so the overall volume ratio is 1:8)

I assumed that being struck by lightning was fairly common, but today I learned I was wrong. Apparently it only kills about 30 Americans per year, and I assumed it was more like 3000, or even 30,000.

As a child, I was in an indoor swimming pool in a house that was struck by lightning, and as a young man, I was in a car that was about 40 feet from a telephone pole that was struck by lightning. In both cases I was fine because of the Faraday cage effect, but the repeated near-misses and spectacular electrical violence made me think that lightning was a non-negligible hazard. I suppose that’s a rationalist lesson: don’t generalize from your experience of rare events if you can actually look up the probabilities.

I guess I wasted all that time training my kids in lightning safety techniques.

Note that 90% of people struck by lightning survive, so that actual number struck per year is more like 300.

Happy birthday! Hope you find a job you are looking for.

Do you know of any gain-of-function “research” done on prions?

Thank you!

Yeah, I mention one or two studies in the article that have to do with altering the host range. There aren’t a lot of prion specialists, of course, but there’s been quite a bit of interest in understanding how they work and spread, so there is some weird stuff out there.

I don’t have the funds to pay for this, but I would like a post about the parasitological component of school-level socialization.

I don’t mean covid or something exotic. I mean the general backdrop of worms, lice, chickenpox, etc. (Bonus points for scabies which in Ukraine, for example, is often considered “a disease of the homeless”, so the parents sometimes lie about their kids having it. I know of one such case, when a whole kindergarten was quarantined.) I think this part of the socializing process is very important but rarely discussed. (Like psychologists prefer to speak about Skills and Insight and Language.) Moreover, when it is discussed, it is not done from the grisly point of view of the population but from the brave point of view of the individual.

Enjoyed this! Very well written. The two arrow graphs, where the second has everything squished down to the bottom, are especially charming

Cooking tainted meat doesn’t denature prions. (They aren’t “alive”, so they can’t be “killed”.) Neither do most biological processes, as you might expect in the normal case of digestion. As the article above mentions, they can persist in the environment for years.

It can take temperatures of several hundred degrees to denature them.

Thank you for the information. Now I feel a lot safer when eating osso buco.

But why is it a ruminant species having these problems again? Why not chickens or whales or fish? Perhaps it’s the grazing lifestyle combined with unnaturally high population densities and immobility. Or herbivores having low natural resistance to prion pathologies.

I believe the ultimate origin of bovine pathogenic prions is in high temperature processing of skins, offal, and especially CNS tissue and bones (prion is expressed in the marrow more than average). Remember, we used to feed bonemeal and other residues of bovine origins to cows until the mad cow episode. Some of that matter had gone through stages like rendering off the fat.

CWD might be a spillover from BSE or have an independent but similar origin.

Why not whales then? They have plenty of lifetime to manifest a prion disease if they get one. Whalers even used to process blubber on ships and tip the reject into sea. But, 1. oceans are immensely larger than pastures and fields, 2. the scale of processing was smaller than in 20th century bovine materials, and 3. nobody fed that material straight back to whales.

I like and respect cows and other ungulates, but they don’t exactly live and die by their wits. A carnivore would have starved long before, and a bird flown into a wall, before we found one in a state in which we sometimes find elk or reindeer. So far the cases in Finland have been of a “non-transmissible” variety. However, the rate of occurence seems higher than in spontaneous Creutzfeld-Jakob disease (humans). A population on the order of 100k (of which only a small portion lives to an advanced age) and a few cases per year. Let’s hope no-one buys American urine based deer attractant on Ebay.

My comment may be considered low effort, but this is a fascinating article. Thank you for posting it.

For farmed dear, we could do genetic engineering to make their PrP immune. It’s a relatively simple change if not for the stigma against genetic engineering.

I’m not convinced that eating prion-contaminated tissue is a major factor in transmitting prion diseases. Prions are still proteins, which are broken down to amino acids very readily by the digestive system. Even if prions are more stable than most proteins because they have formed these crystalline-like oligomers, such large molecules would have little chance of being absorbed intact into the bloodstream. Instead, I would imagine they would pass through the digestive system and be excreted in feces.

The Wikipedia article on kuru proposes an alternate mechanism which seems more plausible to me:

This would allow the prion particles to enter the bloodstream directly where they could be absorbed into tissues and persist for a long time, bypassing the digestive system entirely.

If this is the primary mechanism of transmission, it would support your argument that eating cooked meat would have minimal risk, while handling diseased tissue would actually be the much higher risk activity.

Do you know if any of the 200 people who came down with BSE were involved in handling/butchering the meat, as opposed to just buying contaminated meat at the store and eating it? (I suppose people who bought meat at the grocery store could have still gotten infected during meal prep, but if a substantial number of victims were butchers/slaughterhouse workers/etc., it could be evidence in support of this hypothesis.)

>Prions are still proteins, which are broken down to amino acids very readily by the digestive system.

Not in the case of prions. They are resistant to proteases.

I was thinking more that the acidic environment of the stomach could break down the aggregates to the protein monomers. This step wouldn’t be reliant on proteases, although proteases might then be able to further break down the monomers. But I haven’t looked into whether this has been studied.

Back in 2000s, the official version was that it’s enough to ingest a pepper-grain-sized amount of the infected tissue to be infected with BSE, so maybe the decomposition of the proteins isn’t perfect (in the sense that some molecules might not be taken apart). The ingestion of the tissue is still the official mode of transmission.

The LessWrong Review runs every year to select the posts that have most stood the test of time. This post is not yet eligible for review, but will be at the end of 2024. The top fifty or so posts are featured prominently on the site throughout the year.

Hopefully, the review is better than karma at judging enduring value. If we have accurate prediction markets on the review results, maybe we can have better incentives on LessWrong today. Will this post make the top fifty?

I eat venison nearly every day… and I don’t think I’m stopping. Thanks for the article, though, I’ll be sure to avoid the brain.

Potential for a mad scientist with protein design AI to cause havoc? Yudkowsky mentions prions as a AI method to kill us all?

How much do we know about the presence of prion diseases in other animals we frequently consume?

A quick search shows that even fish have some variant of the prion protein and so perhaps all vertebrates pose a theoretical risk of being the carrier of a prion disease, although the species barrier will likely be too high for prions of non-mammal origin.

I’m quite concerned about pigs.

Apparently pigs are considered to be prion resistant as no naturally occurring prion diseases among pigs have been identified, but it is possible to infect them with some prion strains under laboratory conditions.

A prion disease in pigs could be very bad for two reasons:

1: Pigs are often fed with leftover food from human consumption, this can become a potent vector of prion diseases between pigs.

2: Pork brain, spine, tongue, etc are frequently consumed in some parts of the world, this would make some humans exposed to a large amount of prion protein, if such an illness spreads between pigs.

Fortunately, nothing of this sort happened with pigs yet, and we have been consuming pork brain (and feeding pigs with leftover food) for centuries without known issues (but I doubt pre-modern people would’ve noticed the pattern, since the incubation period can be very long) so maybe pigs are resistant (enough) to prions that pork is very safe.

I think the “always fatal” part of this sentence is vacuous. Unless the meaning is something akin to “kills within X years of contracting the disease”, it can only mean “kills the victim if they don’t die of something else first.” (In fact, the article later says “Humans infected with BSE, meanwhile, can harbor it for up to decades post-exposure, and live an average of over a year after showing symptoms.”)

Wikipedia lists fatal familial insomnia, and two others.

Scrapie, in sheep, has been known since at least 1732, and isn’t thought to spread to humans.

The latter is true of every fatal disease, yes? Alzheimer’s also has a long fuse til death but people don’t recover from it. I’m also told there was a very popular recent television show about a man with terminal cancer who died from other causes.

“Infectious” means “transmissible between people”. As the name suggests, fatal familial insomnia is a genetic condition. (FFI and the others listed are also prion diseases—the prion just emerges on its own without a source prion and no part of the disease is contagious. This is an interesting trait of prions that could not happen with, say, a disease caused by a virus.)

True! I could have talked about scrapie more in this article and didn’t for two reasons-

First, because I looked at some similar transmission tests and it seems to be even less able to convert human PrP.

Second, because as you mention, it’s been around for centuries—if it was going to have spilled over, it probably would have happened by now. CWD, meanwhile, is only a few decades old and has only spread a lot recently- it has more room to explore, so to speak, and some of its possible nearby mutations have never existed around humans before but might now.

As I say in the piece, I think the risk from CWD is in fact low—but this line of reasoning is why human-disease epidemiologists tend to be more concerned about emerging animal diseases than animal diseases that have been around and stable for ages.

Can someone catch FFI from coming into contact with the neural tissues of a patient with FFI?

I suspect it’s possible that FFI genes cause the patient’s body to create prions, but can those prions lead to illness in a person without the FFI gene? If yes, then FFI would still be “infectious” in some sense, I suppose.

Possibly if by “come in contact” we mean like ingesting or injecting or something. That’s the going theory for how the Kuru epidemic started—consumption of the brain of a person with sporadic (randomly-naturally-occuring) CJD. Fortunately cannibalism isn’t too common so this isn’t a usual means of transmission. I think if anything less intensive (say, skin or saliva contact) made CJD transmissible, we would know by now. See also brain contact with contaminated materials e.g. iatrogenic CJD, or Alzheimers which I mention briefly in this piece.

Yep! That’s how it works. Real brutal.

I was thinking of iatrogenic transmissions, yeah (and prions have been a long term psychological fear of mine, too...so I perhaps crawled too much publicly available information about prions to be a normal person)

I wonder if there are any instances of FFI transmitted through the iatrogenic pathway, and whether it is possible to be distinguished from the typical CJD, and whether iatrogenic prions could become a significant issue for healthcare (more instances of prion diseases due to aging population could possibly mean more contaminated medical equipments, and the possible popularisation of brain-computer interface might give us some problems too) given the difficulty of sterilising prions.

Maybe the sample size is too small for us to know.