How to Sleep Better

This is a cross-post from my personal blog.

What is this post about?

Over the summer of 2020, I slept pretty badly for a long period of time and it had pretty noticeable effects on my productivity, perceived energy levels, and well-being in general. This was mostly due to the fact that my room was under the southern roof of the house and it had around 28 degrees Celcius during “cool” summer nights which made it effectively impossible for me to get more than 6 hours of light sleep per night. In autumn, I moved to a new flat where I had to get a new bed, mattress, pillow, etc.

Since I had felt the negative consequences of bad sleep pretty recently, I figured I could conduct a bit of research and use science to improve my own sleep. In the following, you can find a summary of what I found out about the right equipment and behavior to improve sleep mixed with my own considerations.

One piece of framing that I want to provide before diving into the main part is about the money and effort one should be willing to spend to improve our sleep. The longer I thought about this question the more I thought the right answer should be: “a lot”. Just think of the effect that good vs. bad sleep has on your life and quantify it roughly. Let’s assume the difference between good vs. bad sleep results in 30 more productive minutes per day. If you value your time at the level of the minimum wage (as a conservative estimate) which is around 10€ in Germany this means you should be willing to pay up to 5€ per day. Over a year that makes 5 * 365 = 1825€. If you additionally consider all the negative side effects of bad sleep this number gets larger very quickly. If you have, for example, a mattress that is way too soft for you, your spine might suffer which can have large consequences for the rest of your life, e.g. while sitting, driving a car, or during exercise. Treating these outcomes, which are often only revealed after years and take a long time to fix, is often very expensive and emotionally draining or painful. A second example would be our perceived well-being throughout the day. I think we all know that there is a noticeable difference between a day after a good night and a bad one. One day feels slow, annoying, and unproductive while the other feels faster, more energetic, and more productive. While this is harder to quantify financially it is still something that I would be willing to put a lot of effort in to improve consistently.

The right bed

There are a lot of guides out there telling you how to choose the right mattress, pillow, blanket, bed frame, etc. to optimize your sleep. In this chapter, I want to give a broad overview of the different options and how confident we should be in publicly available advice.

Unfortunately, though, I have to start this section with bad news. There is only very little solid and reliable research on the topic of mattresses. This Vice article gives a pretty concise summary of the state of research and the problems it has. Basically, it says that a) research about sleep is always very expensive since you have to distribute a lot of mattresses to a lot of people, b) it is therefore often funded by big mattress companies who have their own interests and the results should be approached with caution and c) private research or privately sponsored research often yields rather imprecise results such as “on average people preferred the medium-firm mattress to the firm one”. But then most mattress companies have their own rating system and there is no unified measurement so results from one company won’t necessarily translate into another. The one trustworthy study that the authors found concluded that no mattress or mattress type is clearly superior to any other in general but for every individual person there are drastically better or worse mattresses. This finding mixed with my personal experience leads me to believe that it makes sense to research mattresses to improve my quality of sleep.

Keeping in mind that they are not research-backed and should rather be interpreted as experience-based heuristics at best, we can look at the recommendations made by people who sell mattresses for a living. This guide gave me a good overview of the parameters that you can choose and should be aware of when buying a new one. The article’s main points are a) the parameters that matter most are your sleeping position, your weight, and your preferred firmness. Depending on them you should get a soft or firmer mattress. b) Mattresses are made of different materials. There are memory foam, latex, innerspring, and hybrid models. Each of which has its advantages and disadvantages with respect to sleep feeling and living age of the mattress. c) You shouldn’t buy mattresses online. Go to a local store and test out different models. Really lie down for five minutes or longer per mattress in contention. If you don’t know exactly what the parameters of your mattress are (which most people don’t) you have to try it out (which is harder to do online). d) Quality comes at a price. It might not be a perfect predictor and you will find some outliers but usually, a more expensive mattress will give you a better sleeping experience. As with most products, there are diminishing returns but given that this choice will have a non-negligible impact on the average quality of sleep over your next 8-10 years you should not aim too low.

There are also different fancy ergonomic pillows and blankets. In both cases, you will find wild claims about how the right choice of either can drastically improve your sleep and decrease negative conditions such as neck pain. However, once again, the research seems to be based to a large extent on privately sponsored or privately conducted research which we should treat with caution.

As stated above I have bought a new mattress following all the guidelines. I think my quality of sleep and my perceived energy levels have increased since and it was worth the price already. But as I have moved to a new flat there are also many other parameters that have changed and it is hard to isolate the impact of the mattress compared to all others. I have also bought a fancy pillow that promised to be especially ergonomic for belly sleepers. Honestly, I mostly bought it out of curiosity and because I low-key wanted to show that these are mostly empty promises without tangible effect. But I was wrong. I really like the new pillow. It fits exactly to my sleeping position and my neck is very relaxed every morning. If you have neck problems after sleeping I would recommend testing out a couple of different pillows, they are astonishingly cheap (20-50 bucks) for the effect that they can have.

From my perspective, the most sensible view of choosing the right mattress, pillow, etc. is that they will yield small improvements for most people but prevent large harms for some. So if your sleep is already pretty OK you can expect a small but tangible improvement. If you have neck pain after waking up or troubled sleep in general, a change of equipment might have a very noticeable positive effect on your sleep and life in general.

A note on your Sleeping position: Appearantly some people believe that one sleeping position is clearly superior to all others and therefore you should actively switch to that. While there are advantages and disadvantages to all positions, e.g. certain sleep-related conditions arise less when you sleep on your back, there is no clear best position. Additionally, it is very hard to train a different position from the one that feels natural to you. So if you don’t have a condition that can clearly be linked to your position (e.g. some instances of snoring) the guides recommend adapting your mattress, pillow, etc. to your position rather than changing your position.

Sleep Hygiene

Even though you can get measurable improvements through a change of equipment the largest improvements probably come only with behavioral changes and putting in some effort—buying a good bike certainly improves your speed but you still have to actually train to get large improvements. In this part of the post, I will talk about everything that can broadly be attributed to a change of surroundings and behavior on our quality of sleep.

Biology behind Sleeping

To understand a bit better why certain behaviors or environments are desirable for better sleep we first need to look at the biology of sleep. If we know how it works we can more easily improve it. Obviously, I will simplify and my neuroscience professor would not be very happy but I will try to give a concise summary of the main concepts.

The Circadian Rhythm describes the 24-hours wake/sleep cycle that most humans experience. It is controlled by multiple parts of the brain one of which is the pineal gland. When the eyes receive sunlight the pineal gland does not produce melatonin and you feel awake. If it doesn’t receive sunlight it does produce melatonin and you feel tired. However, this is clearly not the only mechanism controlling your circadian rhythm—otherwise, we would not experience jetlag. The Suprachiasmatic Nucleus (SCN) is a small subpart of the Hypothalamus that functions as the “master clock”. It is responsible for keeping up the 24-hour rhythm independent of sunlight. This rhythm can be adapted, e.g. when we switch timezones, or forcefully changed in length but it takes time and comes with a potentially high cost to the person’s mental state.

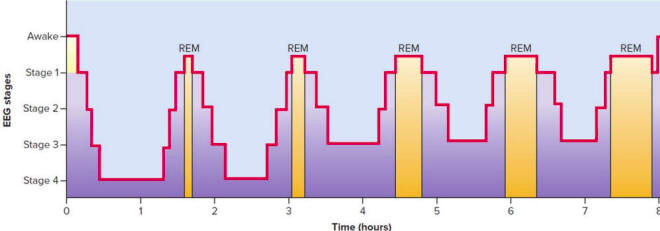

There are different stages and types of sleep. Stage one describes a transition stage where we start to relax. People awakened during this stage often deny that they have been sleeping at all. Stage two describes light sleep but people can still easily be woken up. Stage three is moderate deep sleep and usually starts 20 minutes after stage one. Your muscles are relaxed and vitals (body temperature, blood pressure, and heart and respiratory rates) fall. Stage four is the last stage and it describes very deep sleep. Your muscles are relaxed, vitals are at the lowest level and it is very hard to wake you up. This stage is only reached during the two earliest 90-minute cycles of your sleep. These 90-minute cycles are always between awake and a rapid eye movement (REM) phase or between two REM phases. During every cycle, you will go from a lighter to a deeper stage and come back to a lighter one. The REM phases increase in length over the duration of a night and they are thought to be linked to memory consolidation. The current scientific hypothesis is that you relive memories during the REM phase, strengthen important and weaken unimportant ones.

I will try to use this knowledge to motivate parts of the following heuristics but this is not always possible as our scientific understanding of sleep is rather limited. Measuring stuff in the brain is always hard but gets harder when people can’t communicate because they are asleep. Additionally, many experiments that might yield insights into sleep would involve a lot of sleep deprivation and are often not granted ethical approval.

Sleep-friendly Environment

In which circumstances we sleep can already have a noticeable effect on its quality. Here are some environment-related parameters that one could improve.

Light: As described above, your pineal gland doesn’t produce melatonin when your eyes receive too much light. So if your room isn’t sufficiently dark you will have a harder time falling asleep. If your window is next to a street lamp and you have a bad curtain or blind that you can’t change because your landlord doesn’t allow it I would recommend trying a sleeping mask. It’s a bit weird to get used to but can help wonders once you do. If you have a sleeping rhythm that is compatible with daylight times I would also recommend curtains or blinds that allow in some light to be gradually woken up by sunlight in the morning. In my experience, this is a less disruptive and more pleasant way of waking up.

Noise: Noise can disrupt your sleep and thereby decrease the time you spend in stage three or four. However, this is primarily the case due to abrupt noises, e.g. the squeaking breaks of a car but not so much for regular noises such as the constant flow of cars on a highway as your brain quickly adapts and filters them out. If you sometimes wake up due to noise you should try to sleep with earplugs, they work wonders in hostels but can also improve your regular sleep at home.

Temperature: If you sleep in conditions that are too hot or too cold your sleep will be affected negatively. Most people have probably experienced the upper ends of this scale when sleeping in a very hot room in the summer or the lower end when camping with a light sleeping bag under cold conditions. On average people prefer a room temperature of 18-22 degrees Celcius.

Oxygen: Not much to say here. Your body needs oxygen. This doesn’t stop while we sleep. If possible open a window.

Honestly, I think most of us have been told these things since we were children but are either too lazy to care about them or lack the inertia to e.g. try sleeping masks or earplugs. Thus, this section is less about learning new things but rather a friendly nudge and reminder for you. If you have lacked the inertia to improve these really simple things, order the earplugs now and set yourself an alarm to open the windows before you go to bed.

Behavioural Change

Besides optimizing our environment we can and should also optimize our behavior w.r.t. sleep. There are tons of good guides out there, e.g. by the sleep foundation, the NHS, headspace, James Clear’s blog, and many more which I will try to condense and summarize in the following.

Sleep the right amount: There exist recommendations on the optimal amount of sleep but their help is limited. They recommend that young adults should sleep between 7 and 9 hours and you should adapt your length of sleep based on many conditions including your work, your health, your stress level, the amount of exercise on a given day, your caffeine intake, etc. I guess the most important information is that you should try to prevent sleeping less than 7 hours over prolonged periods of time if you are a young adult. Otherwise, this information is a bit useless as they don’t give clear guidelines on how much I should shorten or extend my average amount of sleep for a given condition. In the ‘Fancy Gadgets’ section, I will explore whether this question can be meaningfully answered by technology.

Make a sleep schedule: All the guides basically agree on two things: a) Do not accumulate sleep debt. If your regular amount is 8 hours per night you can’t replace that with sleeping 6 hours for five nights and then 13 hours for two nights. Sleeping less to learn more in preparation for an exam or similar circumstance also leads to worse performance (see e.g. here). b) Don’t change your rhythm drastically. If you have found a working rhythm, e.g. from 11 pm to 7 am you should not change that. This includes weekends and holidays. The more you change the less rested you will be and the more sleep you need overall. As alluded to above your SCN adapts very slowly and too drastic changes will decrease sleep quality.

Get a pre-bed routine: This essentially boils down to getting yourself physically ready for bed and wind-down mentally. Possible strategies include: stop working, getting away from screens, relaxing exercises such as yoga, meditation or guided wind-downs. My girlfriend uses a sleep routine from headspace and it seems to work well for her. This seems to be different from person to person though. I usually get so bored from the wind-downs that I get annoyed by it and then can’t sleep because I’m annoyed. Another option is to distract your mind and thoughts that keep you awake by listening to podcasts.

Keep your bed for sleep and sex only: Your bed should be a comfort zone and not associated with anything that could cause stress or negative thoughts. If you work or watch Netflix on your bed, you might associate it with negative things or emotional experiences and thereby increase the time you need to get in the zone. While this is sound advice, whether you can actually follow it or not seems to mostly depend on your financial situation. While I was a student my rooms were so small that it was impossible to separate the categories entirely.

Apply pro-sleep behavior during the day: There are plenty of things you can do during the day to improve your sleep at night. You can exercise—it will reduce the time it takes to fall asleep. I think regular intense exercise (e.g. 1h of cycling) has had the biggest positive effect on my overall quality of sleep. See the light of day and reset the melatonin in your brain. Don’t eat too late. The exact reason for why it hampers with sleep quality seems to be unclear but many people report that it does. Don’t drink alcohol. While it may help you to fall asleep it will increase sleep disruptions later when liver enzymes metabolize the alcohol during the night (see e.g. here). Don’t smoke. It is generally terrible for your body, nicotine makes you wake up similar to caffeine and smokers have a higher risk of breathing-related sleep problems during sleep (see e.g. here). Don’t drink too much caffeine, especially close to bedtime.

Try to sleep only when you’re tired: If you can’t sleep there is no point in focusing on it too much. It will only make you feel bad for missing out on important minutes or hours of sleep while time seems to stand still. The general recommendation is that if you can’t fall asleep after 20 minutes of trying you should do something else. Read a book, listen to a podcast, meditate, etc. However, you should avoid bright screens and you should be able to stop the activity whenever you feel tired again and go back to bed.

Screens: While the general recommendation is to avoid screens entirely before sleeping, I think this is not always practical. Sometimes I want to read something online or as a PDF or maybe just watch a dumb YouTube video to wind down. I would recommend using programs like redshift or a native night mode on your computer. You can adjust the color brightness and the amount of red in it to simulate natural light. Since I have started using these programs I don’t have screen-related sleeping problems and I have gotten so used to them that I get headaches and my eyes hurt on computers without these programs. Most modern smartphones also have some sort of night mode that you should activate. It turns the screen black and white and disables most notifications. As soon as it turns on, I just don’t want to look at my phone anymore—it’s astonishingly effective for me.

Power naps: If you are very tired throughout the day you can do power naps. The two things that are always emphasized are a) Don’t power nap too late. Optimally, you should do it after lunch but before 4 pm. b) They should not last longer than 20 minutes. Otherwise, you get into the deeper sleep phases and will feel groggy for the rest of the day. For most people, it requires a bit of training to fall asleep quickly and get back up after 20 minutes but it is manageable with a bit of training. While I was skeptical a few years ago, I now use them regularly. Whenever I feel too tired to be productive I just sleep for 10-20 minutes and return fresh. It’s much preferable to an hour of low productivity after lunch in my personal experience.

Fancy Gadgets

There are many gadgets and apps out there that promise to improve your sleep. While I was very skeptical in the beginning I was still curious and wanted to try one out to see how well it works. I could very quickly exclude all apps that infer your quality of sleep through the motion sensors of the phone which you are supposed to lay on your mattress. While this probably provides some data, this channel seems way too noisy for me to be actually useful. Additionally, these apps don’t incorporate information about your day (e.g. exercise levels) and therefore can’t give you any actionable recommendations.

After reading a bit further I could boil the competition down to two options: the Oura Ring and Whoop. The Oura Ring is, as the name suggests a ring that you keep on all the time and it measures blood flow and other values in your finger to infer heart rate, breathing patterns, etc. Whoop uses a bracelet and basically infers similar information from your wrist instead of your finger. While the Oura Ring is solely focused on sleep, Whoop can also be used for exercising or computing general strain throughout the day. If you want to use the gadget solely for sleep I think none of them are clearly superior. Since I recently picked up cycling again, I also wanted to make use of the exercising functions and therefore decided in favor of Whoop. This video made me curious and convinced me to test Whoop.

I have been using the Whoop strap since October 2020 and so far I found two things. Firstly, the measurements and their interpretations seem to broadly align with my intuition. It detects pretty accurately when I sleep and when I wake up and most of the time when I feel well-rested the app says my recovery is high and when I feel tired the app tells me my recovery is low. However, Whoop uses heart rate variation as a proxy for recovery which is already imperfect for physical activity but definitely doesn’t capture mental activity as much as it should and might thereby skew the results a bit. Secondly, whenever my intuition and whoops measurement disagree, the app is far more often correct than I am. When I wake up and feel good but the app says I’m not well recovered I usually get tired and unproductive earlier than usual. I also think that it is not a self-fulfilling prophecy, i.e. I only get tired because I expect it due to whoop, because I often forget what Whoop told me in the morning and only remember once my unproductive phase hits me.

I don’t think the app is a must-have. The reason why I will probably keep using it and therefore am willing to spend 0.5-1€ per day for it is two-fold: a) Just tracking the amount of sleep I get is already helpful. Even though you might have a rough estimate of the length of last night’s sleep without a sleep tracker, you probably don’t have a good intuition for the last week or last month. Just having the actual numbers is already informative to evaluate your current need or see patterns. And having the app puts more attention on sleep already making it more likely that I prioritize it higher. b) The app is a good indicator of when I need to take a break. When I’m really tired and have an unproductive day, I usually feel bad for not getting things done. If Whoop says that my recovery is terrible after working long, I have to take time off. Since the app “made the decision for me” I don’t feel guilty and can focus on other tasks that need less attention.

After writing the original post, I found eightsleep. It’s a start-up that optimizes everything around sleep and their reviews indicate that they do so quite successfully. Unfortunately, their products are only available in the US and Canada so far and too expensive for me, but when I have more disposable income, I would be curious to try them out.

There is also a new (German) app called Mementor which seems to have pretty promising results in randomized controlled trials (see here). Unfortunately, though, you have to get a prescription from an actual doctor to be allowed to use the app and it is only designed for more serious problems related to sleep so I can’t try it out. If you have personal experience with the app and want to share it please reach out to me.

Conclusions

From my research and my own experiences over the last month I find three main conclusions:

Sleep is very very individual but you can improve your own sleep after finding out what your preferences are. There are no one-fits-all solutions but by thinking about what type of sleeper you are realizing your own bad habits, etc. you can improve your sleep significantly. Especially if you have problems falling asleep, disrupted sleep, or pain in a body part like the spine or neck after sleeping there is a good chance you can solve them.

It makes sense to invest time and money to improve your sleep. Sleep just has a large influence on many things that are important to us. If you are well-rested you are more productive, you feel better, and you are less likely to be annoyed quickly and emotionally hurt the people you like. All of these are things we value highly and thus should be willing to invest time and money to improve.

Most of this seems pretty obvious you just gotta make it a priority and do it. Most of the insights presented in the literature and summarized in this post are not revolutionary. Sleeping the right amount improves how rested you are the next day—no shit. But the fact that they seem so obvious is dangerous because you nearly feel like “you do them already because they make intuitive sense”. However, at least I, find myself too often in a situation where I go to bed too late even though I know that I have to get up early the next morning or do other things that go against the classic advice. I think optimizing your sleep usually is more a problem of implementation rather than lack of knowledge. If you have trouble following the advice I can recommend to nudge yourself and thereby make your choice easier. Use technology to help you. Set yourself a time after which certain behavior is not allowed anymore or make a daily short walk part of your routine.

One last note

If you want to get informed about new posts you can follow me on Twitter or subscribe to my mailing list.

If you have any feedback regarding anything (i.e. layout or opinions) please tell me in a constructive manner via your preferred means of communication.

This is a pet peeve of mine, but: you’re not running out of oxygen as input. Instead exhaust products are building up in the room, of which the most well-known is carbon dioxide. (Outside air outside contains about 500x as much O2 as CO2, and in typical stuffy rooms the ratio is down to about 100x.) For some reason, we seem to be very sensitive to those exhaust products (tho it also seems like this might be a dimension that people vary on significantly).

It’s been a while since I took physiology 101, but I think there was a fairly straightforward explanation. My guess from memory would be that it was something like CO2 having to leave your body during breathing and that depending on the amount of CO2 in the air.

CO2 makes up around 0.04% of the air while oxygen makes up 21%. If you go from 21% of oxygen in the air to 20% that’s not a significant change. The corresponding change of CO2 from 0.04 to something on the order of 0.4% is however massive (the real numbers are a bit off because I don’t want to look up how to calculate it but it goes in that direction).

On practical way that helped my to pay more attention to CO2 was to get a device that measures it 24⁄7 and creates alerts when the levels go over a maximum.

Strongly recommended: rose-colored glasses are Redshift/f.lux for the whole world, not just screens.

I’m mildly disappointed with my Oura ring, although I still use it and don’t actively regret purchasing it; I like having “objective” information on my sleep (gathered from actual sensors on the ring, not just me looking at the clock before going to bed and having to guess how long it took for me to go down), but the distillation from objective sensor data to the information the app shows isn’t super high quality: the sleep-stages breakdown barely registers any REM at all (which I don’t think is biologically plausible), and sometimes it fails to register periods of sleep (e.g., if I woke up at 5 a.m., but am sure I dozed off again from about 6 to 7:30, the latter doesn’t register as part of my night’s sleep, although sometimes it gets picked up as “Rest”). It’s interesting that I seem to spend less time “objectively” asleep than I thought, while still seeming to function OK: the app claims I’m averaging 4 hours, 9 minutes of sleep in 5 hours, 21 minutes in bed per night, which, while surely an underestimate, is less than I would have expected after taking into account how often it seems I was clearly asleep but the app didn’t pick it up. I appreciate the developer API on principle, even if I don’t have any practical need for it. (I did write a program to Tweet about my sleep, but that was also just on principle.)

I’m curious how you actually use the information from your Oura ring? To help measure the effectiveness of sleep interventions? As one input for deciding how to spend your day? As a motivator to sleep better? Something else?

I have found that bed surface cooling devices like the ChiliPad or Eightsleep Pod Pro are excellent. I have the ChiliPad and noticed better sleep straight away. This includes it being easier to get to sleep, less waking up during the night and waking up in the morning more refreshed.

Mattresses are great insulators. If it’s very cold and you’re trying to get warm, they’re fantastic. But if it’s warm and your body needs to shed heat during the night, they’re a problem.

I would recommend these products to anyone who lives in a hot climate and wants to improve their sleep. The bigger you are physically, the more of a difference you will notice from them, as you have more heat to shed and less surface area proportionally to shed it.

I’m surprised how much I liked this post given how much I’ve already read on the topic. It’s well-laid-out and made me feel motivated! :)

Re: noise, earplugs aren’t the only option! Which is good news for anyone who can’t wear them due to sensory issues or a proclivity for ear infections. I use a white noise machine — mine is a Dohm classic, but it’s a matter of personal preference; you can probably also just hook your phone up to a speaker and use that. I absolutely hated white noise machines at first (they give me anxiety, weirdly), but some kind of noise solution was a necessity due to living with a bunch of roommates in a house on a busy street, and I eventually got used to them.

Also, I checked out 8sleep’s website, and their prices are crazy. If you’re really interested in their proprietary mattress technology, then sure, go ahead with that, but don’t buy any of their other sleep accessories! I’ve gotten good-quality versions of all of those products on Amazon for 1⁄3 the price or less.

The recommendation for white-noise machines make me uncomfortable. These can be dangerous.

Except for acute shock damage like from explosions, which is a different mechanism, noise-induced stress is cumulative and will eventually lead to hearing loss. The way I’ve heard it explained is that the hairs in your cochlea build up waste with use and clean it up gradually over time. Too much will poison them and humans are genetically incapable of regeneration, leading to pitch gaps.

They can’t keep up with noise over about 70 decibels and require quiet periods to recover from anything louder. Up to 85 decibels is supposed to be OK for up to about 8 hours [EDIT: other sources say 2?], but you have to stop exposure at that time to recover. Louder noises become dangerous after even shorter exposures. A white-noise machine near your head for 8 hours can prevent that recovery from happening while you sleep. And worse, if it’s over 70 decibels, it can contribute to hearing loss by itself.

Huh, interesting, I haven’t heard of this. Do you have a source handy?

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Auditory_fatigue#Excessive_vibrations

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Noise-induced_hearing_loss#Hair_cell_damage_or_death

These articles have many citations. Both mention reactive oxygen species potentially causing permanent damage.

One article calling out noise machines in particluar: https://www.nbcnews.com/health/kids-health/white-noise-machines-could-hurt-babies-hearing-study-suggests-n41416

CDC page on the topic: https://www.cdc.gov/nceh/hearing_loss/what_noises_cause_hearing_loss.html#:~:text=Sound is measured in decibels,immediate harm to your ears.

The CDC page and the one on noise machine seem to me to make claims about the maximum noise being the problem.

Your above post seems to additionally make the claim that there’s a recovery process that only happens when there’s very little sounds which seems to me like an interesting separate claim from loud noise causes hearing damage.

The Auditory fatigue article mentions that short-term fatigue recovers in about two minutes. Long-term fatigue can take anywhere from minutes to days (i.e. overnight), depending on severity, with most recovery happening in the first 15 minutes.

It also mentions that exercise, heat exposure, and certain chemicals increase the risk of permanent damage. A person with a heavier workload requires more time to recover. These make sense in terms of the metabolic waste model.

Also,

So perhaps the answer isn’t known.

I don’t know exactly how little sound is required for recovery. Perhaps anything under 70 decibels during physical rest is sufficient for the cells to eventually catch up?

There are a lot of scientific papers cited in that article. Maybe some of them can go into more detail on this point.

A practical alternative to white noise machines are nature sounds. Noise patterns like rain did exist in the natural enviroment and are likely more healthy then white noise. You likely still shouldn’t make them too loud.

I have found that sleeping with tape over my mouth improves my sleep quality. I know this sounds crazy, but if you do a quick Internet search you will find support for the practice.

I’ve heard about that, but I think it only make sense to try if you diagnose yourself as a mouth- breather?

I don’t think I’m a mouth-breather.

I saw this interview some months ago, the author indeed claims this “technique” helps you breath through your nose.

Anyone really had good long-term experience with earplugs? I use them during vacations in various conditions and it’s usually a life saver, but after a couple of nights my ears get sore and I dread the thought of putting in earplugs AGAIN. Don’t really feel it’s something I can use at home on regular basis. Also at home I usually don’t have problems with noise, so maybe it’s not a high priority intervention.

Yeah, I use wax earplugs every night. The downside is that they’re gross and they sometimes cause itches, but they always go away if I scratch a bit. The upside is that you cut out a large portion of unexpected sounds, which to me way outweighs the problems.

These can be made with different materials. You might tolerate a different kind better. You could also try earmuffs, which don’t have to go inside your ears, although they could be awkward for side sleepers.

I’d also be worried about not being awakened by a smoke alarm, although deaf people get strobes for those.

Look for custom form fitting earplugs. I find the generic throwaway ones uncomfortable and wouldn’t be able to sleep with them. Custom ones are made based on a mold of your ear and fit perfectly and are more expensive. The ones I have fit snugly enough that I feel no discomfort wearing them in general and only a little when sleeping on my side (with pressure on my ear through the pillow). I’ve slept with them 5 days of the week for the last half year which has improved my sleep significantly because I am very sensitive to noise. They also work well when traveling.

This is a bit surprising to me. I have custom fitted earplugs for protecting my ears against loud music will still letting me hear the music clearly. I wouldn’t wear those to sleep because they are made out of silicon and thus harder then throwaway ones.

If you found a specific brand of custom fitted earplugs very comfortable it would be great to know which one worked for you.

Thanks for this piece of advice—I actually invested in custom earplugs, it cost me around 60eur and 2h of visits and commute. They are not really perfectly comfortable in the night, but they help in the morning, when my Wife gets up earlier than me, she doesn’t wake me up anymore.

Good write up. Do you think that by having whoop’s data available, you began nudging yourself toward a different rhythm (even not entirely consciously)?

I agree with your conclusions. Sleep seems like an obviously easy thing to do, but somehow many people drift away from an optimal equilibrium. I know I did, for a couple of years, until I realized it about a year ago. I began taking sleep supplements (valerian root), which brought instant and welcome relief. However, this didn’t help with the underlying problem, so I couldn’t sleep well if I didn’t take the supplement.

2-3 months ago, I read some comments on ACX about CBT for insomnia. I obtained “Say Goodnight to Insomnia”, a self-guided CBT course that takes 6 weeks. It begins by going over much of what is written in this post, then the 6 week course starts. By week 3, I was falling asleep without any supplements 4-5 nights a week and waking up rested, as if by miracle.

I think what helped me was:

understanding that my body knows best how much sleep it needs. Before, I was getting anxious about not getting enough sleep, which prevented me from sleeping, which made me more anxious, etc. A vicious cycle. Understanding this somehow made the anxiety go away. This also brought a change of habits—I don’t force myself to sleep, and only sleep when I’m tired.

taking sleep hygiene seriously. No screens an hour before bed, adding cardio to my exercise routine, ensuring that the window is open and that the temperature will be just right.

I didn’t even get to week 4 because right now, I’m doing good enough that I only take the sleeping supplement maybe 1 times a week, usually after a more stressful day.

Sounds cool, I’m tempted to try this out, but I’m wondering how this jives with the common wisdom that going to bed at the same time every night is important? And “No screens an hour before bed”—how do you know what “an hour before bed is” if you just go to bed when tired?

I don’t adhere to these guidelines strictly, which helps when they conflict. For example, if I’m tired before my usual bed time, then the “no screen rule” goes out the window because I won’t have trouble sleeping. And when I’m not tired by my usual bed time and haven’t been looking at a screen, then I have plenty of paperbacks to keep me company (or exercise, or cooking, etc.) before I eventually get tired and fall asleep.

Practically, this means that I don’t use screen after 9pm. I usually fall asleep between 9:30pm and 11:00pm, where the median is around 10:15pm or so. I guess this variance comes from different days, days when I do a lot of exercise or little, days with plenty of sun or just a bit, etc.

I don’t think whoop influenced my rhythm that much. But I had quite a steady rhythm already, so it wasn’t too much of a problem. I think I mostly profited from whoop by having an assessment for my quality of sleep. This made it much easier for me to decide how to prioritize my work, e.g. when I should do intellectually intense stuff and when light work.

I haven’t tried any of your other suggestions, e.g. CBT, so I cannot comment on them. But thank you for sharing your experiences.

After going to an actual sleep doctor one of the surprising suggestions from the doctor was that sleeping on a flat surface can be supoptimal and having a mattress at an angle where the head is significantly higher then the feet can be helpful. Of course instead of changing the actual angle of the mattress cushions can produce similar effects.

The effect of applying the suggestion lead to me body relaxing in ways I didn’t expect but I had the impression that after 1-2 months of adaption the effect wasn’t there as strong anymore.

Changing the angle of the mattress from time to time is likely useful and underrecommended.

People who sell mattresses for a living have bad incentives in getting you to make useful purchasing decisions. For organizations such as consumer reports the incentives are much better aligned. Paying customer reports for their mattress ratings costs money but information is valuable and worth paying for.

Thank you for the post.

It motivated me to really invest more time and effort into sleep quality—although I think it’s pretty good it should be worth exploring if my productivity can be improved by better sleep

Summarized most of the things I knew already: sleep cycles, avoid screens etc

Motivated me to do something with the things I knew already (it’s 11pm and I’m writing this on my full-brightness phone) *Motivated me to try something new: an app or a fancy gadget

Based on my experience with circadian rhythm issues (delayed sleep phase syndrome etc.):

- Turning off the blue light in your devices in the evening is probably less impactful than lowering the brightness of your devices in the first place. Do both, but don’t expect a blue light filter to work if the device is still blasting your eyeballs.

- Many indoor environments are underilluminated. Your bedroom is probably 100x times darker than the sun. That’s not an exaggeration—we just don’t notice because we perceive light on a curve. Get much brighter lights. Going as bright as direct sunlight is too expensive, but you can easily get 10% of the way there, and it will stabilize your sleep (as long as you put the lights on a timer so they match the actual sun!) Get lights with a 90+ CRI, otherwise they will feel harsh.

- It should be a few degrees colder in your bedroom when you want to go to sleep, than the rest of the building is during the day.

- I never had success with melatonin: your body adapts too quickly when it’s used as a sedative, and the effects of using it in smaller doses as a circadian-rhythm shifter (a few hours before bedtime) were mild to nonexistent for me.

A thought: if you required large doses of melatonin for use as a sedative, maybe you simply needed to use a larger dose than you tried for circadian shifting as well, or longer before bedtime [I would suggest the latter first]. Melatonin definitely shouldn’t have no effect unless something is particularly wrong [perhaps a bad batch, anxiety, or a physical problem]. (It will change your circadian rhythm, but that is only one aspect of whether you actually sleep.) I have noticed no tolerance effects whatsoever when used as a circadian shifter, though there were some when used as a sedative.

I personally find melatonin extremely useful, taking a significant dose four to six hours before I plan to sleep. (My body otherwise thinks days are about 28-30 hours long.) By the time I actually try to sleep, it is trivial to do so, even though I had severe insomnia. It still works even if it is out of your system by then, and will not impact the quality of the sleep [I do not like the effects of it on my first few hours of sleep if I use it as a sedative], just its ease.

Your other points seem reasonable and important to keep in mind.

Unrelatedly, if you are overweight, that might be a cause of insomnia. I know my weight had a large effect in increasing my insomnia [due to lack of comfort and physical issues]. Losing it helped quite a bit, though I still need circadian shifting.

edit: Removed an extraneous word and fixed a spelling error.

I should note that my sleep issues are completely under control now, primarily due to the light therapy, as well as making sure I wake up at the same time every day, even on weekends. I now sleep like a normal, healthy person.

For a long time, especially when I was living in a dim basement, I had bouts of non-24 hour sleep-wake rhythm and I even had periods of irregular sleep-wake rhythm, which was a nightmare. So the light therapy etc. has taken me a long way. Fixing my sleep also played a large role in fixing my depression (and vice versa), since the comorbidity between depression and circadian rhythm disorders is very high (I think I remember >50%)

As for melatonin, I was never able to tell for sure if it was having an effect, but it definitely wasn’t solving my sleep issues as the other stuff did. Maybe there’s some biological variability in response to it or something. I did try different doses, up to the sedative level, and it never really helped. I’m glad some people find it helpful though.

There’s no sedative level and most melatonin products have doses that are too high to be clinically effective. What was the lowest dose you took?

There is, in fact, a sedative level, and higher doses aren’t less effective, they just induce more side effects, from what I understand. I tried every dose under the sun, including tiny ones. The effect was always weak at best.

Scott does write “A meta-analysis of dose-response relationships concurred, finding a plateau effect around 0.3 mg, with doses after that having no more efficacy, but worse side effects” but that doesn’t mean that higher doses keep their efficiency.

His article for example goes on to say “And Pires et al studying 22-24 year olds found that 0.3 mg worked better than 1.0.” Which is likely

Where did you get the idea that there’s a sedative level for melatonin?

Honestly, it’s a little strange that light therapy would help and melatonin not (since light therapy shifts circadian rhythms via [probably] lowering your melatonin levels in the morning). It’s good you have your sleep issues under control.

The effect size of melatonin use is usually pretty small. I think most studies say it shifts your cycle by 10-20 minutes. As I tended to go to bed an hour or two later every night, this was not enough.

As for light therapy, it’s not strange that it would have a different effect. Light stimulates a neural pathway going straight to your suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), which is the core circadian clock in your brain. (Melatonin is not involved in this, though melatonin is affected downstream.) Melatonin, on the other hand, is released by the pineal gland and is used to regulate the SCN (among other things), but it’s not involved directly in the core timing mechanisms of the SCN.

Melatonin actually causes a shift much larger than ten to twenty minutes -when taken early. Melatonin taken in the morning causes a large shift to delay the cycle (this can cause a shift of several hours). Melatonin taken after several hours hastens the cycle, also by hours. If this weren’t the case, it would be useless as I currently use it. The ten to twenty minutes is as a sedative, when taken twenty minutes before bedtime.

There are, of course, a number of pathways affecting sleep timing, including the uninformatively named System X that just tries to keep track of time by dead reckoning. I believe, perhaps wrongly, that the SCN’s sleep related functions are mostly directly by melatonin; melatonin reduces the firing rates of the parts of the SCN that increase in firing rate in the presence of light (according to Wikipedia). This is the core timing mechanism of how light affects the SCN, isn’t it?

Edit: Looking at it again, the relevant part of the SCN article ( https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Suprachiasmatic_nucleus )(in the electrophysiology section) does not have direct citations, but I’ll assume it’s correct unless this activity of melatonin is directly disputed.

Edited again: An edit changed the structure of what I was saying, making for a strange sentence I don’t endorse.

I would highly suggest that anyone interested in sleep check the first few episodes of the Huberman Labs podcast, which are focused on this very issue: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nm1TxQj9IsQ&list=PLPNW_gerXa4Pc8S2qoUQc5e8Ir97RLuVW&index=28

(Confusingly, the playlist is in reverse order.)

The take-away are likely to be different for different people (a lot of mechanisms and techniques are covered), but for me they were:

1. cold showers in the morning—those really wake me up and flush away the grogginess that normally persists for a long time

2. step outside and get sunlight in your eyes in the morning, which helps maintain your waking time and/or shift it earlier (I’m naturally prone to go to bed later and later)

3. it’s better to have a consistent sleep duration than to make up for short sleep by sleeping long

The third point of advice in particular was something I’d never heard of and that ran counter to the gist of what I’d heard before. But empirically, it seems to be true—I’m always more tired when I suddenly start sleeping more than I did in the previous days.

Implementing mostly these three points, I got to the point where I could get on with 6 hours of sleep per night with what feels like normal productivity, something that would be absolutely unattainable previously (I think 6 hours is too short, and I want to aim for 7:30 of sleep for about 8 hours in bed in the long run).

I also benefitted a lot from using earplugs and a face mask. Something that I started to do one month or two before applying the advice from the podcast, and might have contributed to the good results.

An awful lot of this boils down to comfort. If you aren’t comfortable, it will be much harder to sleep, and its quality will go down. Anything that causes discomfort will have this effect, regardless of whether it is commonly mentioned in regards to sleeping, and also regardless of whether it is physical or mental.

I feel similarly, and still struggle with turning off my brain. Has anything worked particularly well for you?

Fascinating article, two things:

On average people prefer a room temperature of 18-22 degrees Celcius.

Are you sure? That looks really cold. My thermodynamics book said 26 C is the best temperature for confort for humans.

2. What about install sound absorbing panels on the walls for sound insulation? Sounds more confortable then earplugs and work both ways, so you can be noisy without giving trouble to the neightbours

What’s warm depends a lot on the clothing. I think there’s a good chance that the thermodynamics book speaks about 26 C for naked humans.

Yes of course

I happen to be looking into sound insulation right now. My understanding is that panels on the walls mostly improves the quality of sound within the room rather than actually prevent sound from getting in or out (which is something that requires good walls, and potentially plugging individual leaks such as through a door.

I haven’t yet gotten a clear sense of whether there’s a way to increase room noise isolation without major architectural overhauls.

In my area, typical room temperature is 20-22 C, so 26 seems a bit high, but this might be cultural. Humans are a tropical species and couldn’t survive winter in the temperate zones without clothing, shelter, and fire. I’d call 26 C “warm”, but it seems well within my long-term tolerable range.

But there are significant temperature differences between day and night. I think you can go as low as 15 C before I’d call it “cold”. I’d be OK without a shirt and blanket at night at 15 C. Just a bed sheet. I sleep on memory foam though.

Perception of temperature is mostly cultural yes, what do you think about putting sound absorbing panels on the walls of the room?

Seems like it would help if noise is a problem. More expensive than earplugs, and I’m not sure how durable they are. There may be some safety issues, but it seems less bad than the earplugs.