Nuclear war is unlikely to cause human extinction

A number of people have claimed that a full-scale nuclear war is likely to cause human extinction. I have investigated this issue in depth and concluded that even a full scale nuclear exchange is unlikely (<1%) to cause human extinction.

By a full-scale war, I mean a nuclear exchange between major world powers, such as the US, Russia, and China, using the complete arsenals of each country. The total number of warheads today (14,000) is significantly smaller than during the height of the cold war (70,000). While extinction from nuclear war is unlikely today, it may become more likely if significantly more warheads are deployed or if designs of weapons change significantly.

There are three potential mechanisms of human extinction from nuclear war:

1) Kinetic destruction

2) Radiation

3) Climate alteration

Only 3) is remotely plausible with existing weapons, but let’s go through them all.

1) Kinetic destruction

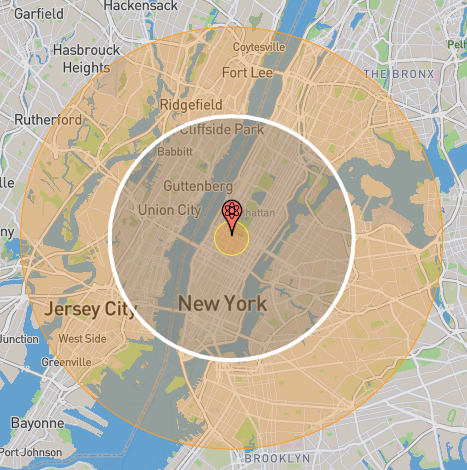

There simply aren’t enough nuclear warheads to kill everyone directly with kinetic force, and there likely never will be. There are ~14,000 nuclear weapons in the world, and let’s suppose they have an average yield of something like 1 megaton. This is a conservative guess, the actual average is probably closer to 100 kilotons. With a 1 megaton warhead, you can create a fireball covering 3 km², and a moderate pressure wave that knocks down most residential houses covering 155 km². The former kills nearly everyone and the latter kills a decent percentage of people but not everyone. Let’s be conservative and assume the pressure wave kills everyone in its radius. 14,000 * 155 = 2.17 million km². The New York Metro area is 8,683 km². So all the nuclear weapons in the world could destroy about 250 New York Metro areas. This is a lot! But not near enough, even if someone intentionally tried to hit all the populations at once. Total land surface of earth is: 510.1 million km². Urban area, by one estimate, is about 2%, or 10.2 million km.² Since the total possible area destroyed from nuclear weapons is ~2.17 million km² is considerably less than a lower bound on the area of human habitation, 10.2 million km², there should be basically no risk of human extinction from kinetic destruction.

If you want to check my work there, I was using nuke map.

The even more obvious reason why kinetic damage wouldn’t lead to human extinction is that nuclear states only threaten one or several countries at a time, and never the population centers of the entire world. Even if NATO countries and Russia and China all went to war at the same time, Africa, South America, and other neutral regions would be spared any kinetic damage.

2) Radiation

Radiation won’t kill everyone because there aren’t enough weapons, and radiation from them would be concentrated in some areas and wholly absent from other areas. Even in the worst affected areas, lethal radiation from fallout would drop to survivable levels within weeks.

Here it’s worth noting that there is an inherent tradeoff between length of halflife and energy released by radionuclides. The shorter the half life the more energy will be released, and the longer the half life the less energy. The fallout products from modern nuclear weapons are very lethal, but only for days to several weeks.

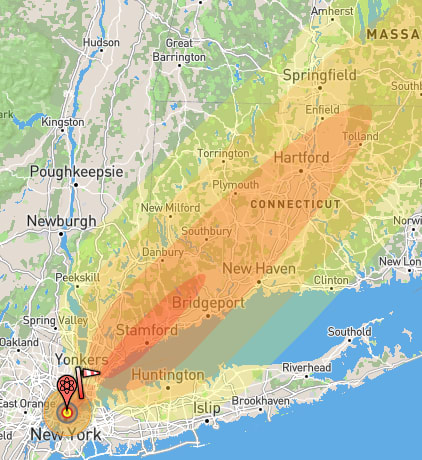

Let’s try the same calculation we used with kinetic damage, and see if an attack aimed at optimizing fallout for killing everyone could succeed. Using Nukemap again, I’ll go with the fallout contour for 100 rads per hour. 400 rads is thought too be enough to kill 50% of people, so 100 rads per hour is likely to kill most all people not in some kind of shelter. We need to switch to using a groundburst detonation rather than an airburst detonation, because groundbursts create far more fallout. A 1mt ground burst would create an area of about 8,000 km² of >100 rads per hour. Okay, multiple that by 14,000 warheads, and we get 112 million km². That’s a lot! It’s still less than the 510.1 million km² of earth’s land mass, but it’s a lot more than the ~10.2 million km² of urban space. Presumably this is enough to cover every human habitation, so in principle, it might be possible to kill everyone with radiation from existing nuclear weapons.

In practice, it would be almost impossible to kill every human via radiation with the existing nuclear arsenals, even if they were targeted explicitly for this purpose. The first reason is that fallout patterns are very uneven. After a ground burst, fallout is carried by the wind. Some areas will be hit bad and some areas will be hardly affected by fallout. Even if most human population centers were covered, a few areas would almost certainly escape.

Two other things make extinction by radiation unlikely. Many countries, especially in the southern hemisphere, are unlikely to be affected by fallout much at all. Since most of these countries are likely to be neutral in a conflict, and not near combatant countries, they should be relatively safe from fallout. While fallout might travel hundreds of kms, it still won’t reach places separated by greater distances. Fallout that reaches the upper atmosphere will eventually fall back down, but usually after the period of lethal radioactivity. The other mitigating factor is that in typical nuclear war plans, ground bursts are usually restricted to hardened targets, and air bursts are favored for population and industry centers. This is because air bursts maximize the size of the destructive pressure wave. Air burst detonations result in little lethal fallout reaching the ground, so populations not downwind of military targets would likely be safe from the worst of the radiological effects in a war scenario.

The final protection from extinction by radiation is simply large amounts of mass between people and the radiation source, in other words, fallout shelters. After several weeks, the radionuclides in fallout from ground burst detonations will have decayed to the point where humans can survive outside of shelters. Many fallout shelters exist in the world, and many more could be made easily in a day or two with a shovel, some ground, and some boards. Even if lethally radioactive fallout from ground bursts covered all population centers, many humans would still survive in shelters.

The risks of extinction from nuclear-weapon-induced-radiation wouldn’t be complete without discussing two factors: nuclear power plants and radiological weapons. I’m only going to cover these briefly, but they both don’t change the conclusions much.

Nuclear power plants could be targeted by nuclear weapons to create large amounts of fallout with a longer half-life but less energy per unit time. The main concern here is that nuclear power plants and spent fuel sites contain a much greater *mass* of radioactive material than nuclear missiles can carry. The danger comes primarily from spreading the already very radiative spent or unspent nuclear fuel. The risk this poses requires a longer analysis, but the short version is that while nuking a nuclear power plant or stored fuel site would indeed create some pretty long-lived fallout it would still be concentrated in a relatively small area. Fortunately, even a nuclear detonation wouldn’t spread the nuclear fuel more than several hundred km at most. Having regions of countries covered in spent nuclear fuel would be awful, but it doesn’t much raise the risk of extinction.

Radiological weapons are nuclear weapons designed to maximize the spread of lethal fallout rather than destructive yield. The particular concern from the extinction perspective is that they can be designed to create fallout that continues to emit levels of radiation that can make an area uninhabitable for months to years. These kind of radiological weapons kill more slowly, but they still kill. In principle, radiological weapons could be used to kill everyone on earth. However, in practice, the same constraints that apply to standard nuclear weapons apply to weapons optimized for long-lasting fallout, as well as some additional constraints.

Radiological weapons wouldn’t produce more fallout than standard warheads, they would just produce fallout with different characteristics. As a result the amount of radiological weapons required to cover every part of earth’s surface would be massively expensive (likely as expensive as the largest existing nuclear arsenals), and serve no military purpose. Their inefficiency in destruction and death compared to standard nuclear weapons is probably why radiological weapons have never been developed or deployed in large numbers. This makes them an ongoing theoretical concern, but not an existential risk in the immediate future. A concerning development is Russia’s claim to have developed a large-yield (100mt) submersible nuclear weapon with the suggestion that it could be used as a radiological weapon, but even if this is true, it’s unlikely to be deployed in large numbers.

3) Climate alteration

The bulk of the risk of human extinction from nuclear weapons come from risks of catastrophic climate change, nuclear winter, due to secondary effects from nuclear detonations. However, even in most full-scale nuclear exchange scenarios, the resulting climate effects are unlikely to cause human extinction.

Reasons for this:

a) Under scenarios where a severe nuclear winter occurs as described by Robock et al, some human populations would likely survive.

b) The Robock group’s models are probably overestimating the risk

c) Nuclear war planners are aware of nuclear winter risks and can incorporate these risks into their targeting plans

Before diving into each subject, it’s worth understanding the background of nuclear winter research. In the 1980s a group of atmospheric scientists proposed the hypothesis that a nuclear war would result in massive firestorms in burning cities, which would loft particles high into the atmosphere and cause catastrophic cooling that would last for years. Many found it alarming that such an effect could be possible and go unnoticed for decades while the risk existed. Some scientists also thought the proposed effect was too strong, or unlikely to occur at all. Until a few years ago, if you looked only at peer reviewed literature you would only find papers forecasting severe nuclear winter effects in the event of a nuclear war. Understandably, many people assumed that this was the scientific consensus. Unfortunately, this misrepresented the scientific community’s state of uncertainty about the risks of nuclear war. There have only ever been a small numbers of papers published about this topic (<15 probably), mostly from one group of researchers, despite the topic being one of existential importance.

I’m very glad Robock, Toon, and others have spent much of their careers studying nuclear winter effects, and their models are useful in estimating potential climate change caused by nuclear war. However, I’ve become less convinced over time the Robock model is largely correct. See section B below for why I’ve changed my mind. However, I’m quite uncertain about the probability of strong cooling effects from nuclear war, and am still quite concerned about the potential for severe cooling, even if the risk of extinction from such events is small.

A: Under scenarios where a severe nuclear winter occurs as described by Robock et al, some human populations would likely survive.

The latest and most detailed model of potential cooling effects from a fullscale nuclear exchange comes from, Robock et al., “Nuclear winter revisited with a modern climate model and current nuclear arsenals: Still catastrophic consequences” found here.

The effects from this model are severe. In the 150Tg case, after a year, summer temperatures in the Northern hemisphere are 10-30 degrees C cooler. The effects are less severe at the equator (5 degrees C), but basically all places in the world are affected. The most likely outcome is that most people starve to death. Many would freeze too, but starvation is likely the greatest risk. Even in this model, it appears that in equatorial regions, some farming would still be possible, enough for some populations to survive. After a 10-15 years, agriculture in most of the world would be possible at reduced capacity.

Carl Shulman asked one of the authors of this paper, Luke Oman, his probability that the 150Tg nuclear winter scenario discussed in the paper would result in human extinction, the answer he gave was “in the range of 1 in 10,000 to 1 in 100,000.” This strikes me as quite plausible, though one expert opinion is no substitute for a deep analysis. The Q&A with Oman contains his reasoning for this assessment.

Two different analyses are required to calculate the chances of human extinction from nuclear winter. The first is the analysis of the climate change that could result from a nuclear war, and the second is the adaptive capacity of human groups to these climate changes. I have not seen an in depth analysis of the latter, but I believe such an assessment would be worthwhile.

My own guess is that humans are capable of surviving far more severe climate shifts than those projected in nuclear winter scenarios. Humans are more robust than most any other mammal to drastic changes in temperature, as evidenced by our global range, even in pre-historic times. While a loss of most agriculture would likely kill most people on earth, modern technology would enable some populations to survive. Great stores of food currently exist in the world, and it is l likely that some of these would be seized and protected by small groups, providing enough food to last for years. While even such populations with food stores wouldn’t have enough to survive for 10-15 years, such food stores would give groups time to adapt to new food sources. The organization ALLFED has explored a number of alternative food sources that could keep populations alive in the event of a nuclear war or other large solar disruption, and I expect great necessity to drive the discovery of even more in the event of such a disaster.

B: The Robock group’s models are probably overestimating the risk

The nuclear winter model at its simplest: Nuclear detonations → Fires in cities → Firestorms in cities → Lofted black carbon into the upper atmosphere → black carbon persists in upper atmosphere, reflecting sunlight and causes massive cooling

Each step is required in order for the effect to occur. If nuclear war causes massive fires in cities but does not lead to firestorms that loft particles, then no long term cooling is going to occur. Some of these steps are easier to model than others. Based on my reading of the literature, the greatest uncertainties involve the dynamics of cities burning after a nuclear attack, and whether the conditions would produce firestorms sufficient to loft large numbers of particles high enough in the atmosphere to persist for years.

We’re finally beginning to see some healthy debate about some of these questions in the scientific literature. Alan Robock’s group published a paper in 2007 that found significant cooling effects even from a relatively limited regional war. A group from Los Alamos, Reisner et al, published a paper in 2018 that reexamined some of the assumptions that went into Robock et al’s model, and concluded that global cooling was unlikely in such a scenario. Robock et al. responded, and Reisner et al responded to the response. Both authors bring up good points, but I find Reisner’s position more compelling. This back and forth is worth reading for those who want to investigate deeper. Unfortunately Reisner’s group has not published an analysis on potential cooling effects from a modern full scale nuclear exchange, rather than a limited regional exchange. Even so, it’s not hard to extrapolate that Reisner’s model would result in far less cooling than Robock’s model in the equivalent situation.

C: Nuclear war planners are aware of nuclear winter risks and can incorporate these risks into their targeting plans

A very simple way to reduce risks from nuclear winter is to refrain from targeting cities with nuclear weapons. The proposed mechanism behind nuclear winter results from cities burning, not ground bursts on military targets. I’ve spoken with some of the officials in the US defense establishment responsible for nuclear war planning, and they’re well aware of the potential risks from nuclear winter. Of course, being aware of the risks does not guarantee they will have reasoned about the risks well, or have engaged in good risk management practices. However, the fact that this risk is well publicized makes it more likely that nuclear war planners will take steps to minimize blowback risk from climate effects.

It’s hard to know to what extent this has been done. Nuclear war plans are classified, and as far as we know current US nuclear war plans do target cities under some circumstances but not under others. However, the defense establishment has access to classified information and models that we civilians do not have, in addition to all the public material. I’m confident that some nuclear war planners have thought deeply about the risks of climate change from nuclear war, even though I don’t know their conclusions or bureaucratic constraints. All else being equal, the knowledge of these risks makes military planners less likely to accidentally cause human extinction.

Conclusion

This post discussed the three plausible mechanisms of human extinction caused by nuclear weapons. The fact that one of these mechanisms, nuclear winter, wasn’t characterized until the 1980s, is a good reminder of the possibility of unknown unknowns. While nuclear tests provided information about the effects of these weapons, the test environments were significantly different than war environments. Large model uncertainties remain. Given that the greatest existential threat from nuclear war appears to be from climate impacts, it would be great to see more researchers study the climate effects from nuclear war and the resilience capacity of different human groups.

There appear to be several interventions possible for reducing existential risk from nuclear war. At the policy level, a commitment from the largest nuclear powers to refrain from targeting the majority of cities would reduce risk of accidental omnicide. Improving the maximum resilience capacity of human populations best positioned to survive a nuclear winter would also make humanity less vulnerable to nuclear winter, and could also protect against other existential threats.

Further reading

Toby Ord conducts a quantitative estimate of extinction risk from nuclear war in:

The Precipice: Existential Risk and the Future of Humanity

Nuclear War as a Global Catastrophic Risk

Nuclear winter and human extinction: Q&A with Luke Oman (by Carl Shulman)

Nuclear Winter Responses to Nuclear War Between the United States and Russia in the Whole Atmosphere Community Climate Model Version 4 and the Goddard Institute for Space Studies ModelE

Climate Impact of a Regional Nuclear Weapons Exchange: An Improved Assessment Based On Detailed Source Calculations

Comment on “Climate Impact of a Regional Nuclear Weapon Exchange: An Improved Assessment Based on Detailed Source Calculations” by Reisner et al.

https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1029/2019JD030777

Reply to Comment by Robock et al. on “Climate Impact of a Regional Nuclear Weapon Exchange: An Improved Assessment Based on Detailed Source Calculations”

https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1029/2019JD031281

Comparing Economic and Crop Models: The Case of Climatic and Agricultural Impacts of Nuclear War

https://www.gtap.agecon.purdue.edu/resources/download/9185.pdf

- The title is reasonable by (20 Sep 2025 8:59 UTC; 196 points)

- Book Launch: “The Carving of Reality,” Best of LessWrong vol. III by (16 Aug 2023 23:52 UTC; 131 points)

- Voting Results for the 2020 Review by (2 Feb 2022 18:37 UTC; 108 points)

- Prizes for the 2020 Review by (20 Feb 2022 21:07 UTC; 94 points)

- The Illustrated Petrov Day Ceremony by (26 Sep 2025 21:01 UTC; 93 points)

- 2020 Review Article by (14 Jan 2022 4:58 UTC; 74 points)

- Convince me that humanity *isn’t* doomed by AGI by (15 Apr 2022 17:26 UTC; 61 points)

- Precise P(doom) isn’t very important for prioritization or strategy by (14 Sep 2022 17:19 UTC; 14 points)

- Research project idea: Direct and indirect effects of nuclear fallout by (EA Forum; 15 Apr 2023 14:48 UTC; 12 points)

- Great Power Conflict by (EA Forum; 15 Sep 2021 15:00 UTC; 11 points)

- Great Power Conflict by (17 Sep 2021 15:00 UTC; 11 points)

- The Convergent Path to the Stars—Similar Utility Across Civilizations Challenges Extinction Prioritization by (EA Forum; 18 Mar 2025 17:09 UTC; 8 points)

- 's comment on CFAR Handbook: Introduction by (10 Sep 2022 6:08 UTC; 7 points)

- 's comment on TurnTrout’s shortform feed by (25 Jan 2022 22:00 UTC; 7 points)

- 's comment on Voting Results for the 2020 Review by (12 Feb 2022 22:28 UTC; 6 points)

- The Convergent Path to the Stars by (18 Mar 2025 17:09 UTC; 6 points)

- 's comment on Petrov Day Retrospective, 2023 (re: the most important virtue of Petrov Day & unilaterally promoting it) by (28 Sep 2023 16:07 UTC; 5 points)

- 's comment on QubitSwarm99′s Quick takes by (EA Forum; 3 Oct 2022 20:13 UTC; 3 points)

- 's comment on Slowing down AI progress is an underexplored alignment strategy by (25 Jul 2023 1:37 UTC; 2 points)

This will not be a full review—it’s more of a drive-by comment which I think is relevant to the review process.

I am extremely skeptical of and am not at all confident in this conclusion. Ellsberg’s The Doomsday Machine describes a horribly incentivized military establishment which pursued bloodthirsty and senseless policies, deceiving their superiors (including several presidents), breaking authentication protocols, refusing to adopt plans which didn’t senselessly destroy China in a conflict in the Soviet Union, sub-delegation of nuclear launch authority to theater commanders and their subordinates (no, it’s not operationally true that the US president has to authorize an attack!), lack of controls against false alarms, and constant presidential threats of first-use. The USAF would manipulate presidential officials in order to secure funding, via tactics such as inflating threat estimates or ignoring evidence that the Soviet Union had less nuclear might than initially thought.

And Ellsberg stated that he didn’t think much had changed since his tenure in the 50s-70s. While individual planners might be aware of the nuclear winter risks, the overall US military establishment seems insane to me around nuclear policy—and what of those in other nuclear powers?

However, The Doomsday Machine is my only exposure to these considerations, and perhaps I’m missing a broader perspective. If so, I think that case should be more clearly spelled out, because as far as I can tell, nuclear policy seems like yet another depravedly inadequate facet of our current civilization.

I’m fairly confident that at least some nuclear war planners have thought deeply about the risks of climate change from nuclear war because I’ve talked to a researcher at RAND who basically told me as much, plus the group at Los Alamos who published papers about it, both of which seem like strong evidence that some nuclear war planners have taken it seriously. Reisner et al., “Climate Impact of a Regional Nuclear Weapons Exchange: An Improved Assessment Based On Detailed Source Calculations” is mostly Los Alamos scientists I believe.

Just because some of these researchers & nuclear war planners have thought deeply about it doesn’t mean nuclear policy will end up being sane and factoring in the risks. But I think it provides some evidence in that direction.

I’ve edited the original to add “some” so it reads “I’m confident that some nuclear war planners have...”

It wouldn’t surprise me if some nuclear war planners had dismissed these risks while others had thought them important.

The post claims:

This review aims to assess whether having read the post I can conclude the same.

The review is split into 3 parts:

Epistemic spot check

Examining the argument

Outside the argument

Epistemic spot check

Claim: There are 14,000 nuclear warheads in the world.

Assessment: True

Claim: Average warhead yield <1 Mt, probably closer to 100kt

Assessment: Probably true, possibly misleading. Values I found were:

US

W78 warhead: 335-350kt

W87 warhead: 300 or 475 kt

Russia

R-36 missile: 550-750 kt

R29 missile: 100 or 500kt

The original claim read to me that 100kT was probably pretty close and 1Mt was a big factor of safety (~x10) but whereas the safety factor was actually less than that (~x3). However that’s the advantage of having a safety factor – even if it’s a bit misleading there still is a safety factor in the calculations.

I found the lack of links slightly frustrating here – it would have been nice to see where the OP got the numbers from.

Examining the argument

The argument itself can be summarized as:

Kinetic destruction can’t be big enough

Radiation could theoretically be enough but in practice wouldn’t be

Nuclear winter not sufficient to cause extinction

One assumption in the arguments for 1 & 2 is that the important factor is the average warhead yield and that e.g. a 10Mt warhead doesn’t have an outsized effect. This seems likely and a comment suggests that going over 500kt doesn’t make as much difference as might be thought and that is why warheads are the size that they are.

Arguments 1 & 2 seem very solid. We have done enough tests that our understanding of kinetic destruction is likely to be fairly good so I don’t have much concerns there. Similarly, radiation is well understood and dispersal patterns seem kinda predictable in principle and even if these are wrong the total amount of radiation doesn’t change, just the where it is.

Climate change is less easy to model, especially given that the scenario is a long way out of our actual experience. To trust the conclusion we have to trust the models. I haven’t looked into this – different researchers have come to different conclusions and we hope that the true value is between the worst and best case found (or at least not too much worse than the worst case).

One thing that I found frustrating in the post is that the <1% risk of human extinction from full scale nuclear war is given but the post is not explicit which arguments give such high confidence. The post rightly refers to a number of steps which need to happen to make catastrophic climate change happen:

Given a nuclear exchange how probable are firestorms?

Given firestorms how probable is black carbon to be lifted into the atmosphere?

Given lofting, how probable is it to stay aloft for sufficient time?

Given long term cooling, how probable is human extinction?

But it is not explicit as to which step(s) are most improbable.

The OP points towards an exchange between Robock and Reisner (could a small scale conflict cause a nuclear winter?) where it finds Reisner’s position more compelling. However, finding the position more compelling does not suggest to me that this part of the logic chain can be doing much heavy lifting.

(similarly, I don’t think military planners being aware of the danger of nuclear winter can be doing much heavy lifting to get us up to <1% probability).

So the main part of the logic to conclude high confidence must be that even catastrophic climate change would not cause human extinction.

The OP quotes Luke Oman as saying he believed that it would be ~1 in 10,000 to 1 in 100,000. It also links to him giving his reasoning. This is based mainly on the Toba supervolcano and other similar events failing to wipe out humanity’s ancestors and that the southern hemisphere is likely to be less badly hit than the north in a nuclear exchange. (I would have liked this to have been summarized in the OP as it is probably the strongest argument for non-extinction).

The interview doesn’t go into enough detail for me to assess how strong Luke’s arguments are and this makes it hard for me to get the same level of confidence that Luke has – how close an analogy to full scale nuclear war is Toba likely to be?

The post also suggests food stores and human ingenuity as reasons to think that humanity would avoid extinction.

Given how key this part of the logic chain seems to be I would have liked this section to be more detailed.

Outside the argument

I would have also liked the post to consider uncertainty outside the argument.

A few comments point out other possible mechanisms which might cause additional risk:

Triggering supervolcano

New technologies

Inability to restart civilisation

Giving <1% probability that full scale nuclear war will cause human extinction implies sufficient confidence that we have thought of all the possible causes of extinction and/or that other possible causes will have similarly low probability of extinction.

This isn’t discussed in the OP which seems like a weakness.

Conclusion

I think that the post (plus the link to the Luke Oman interview) give sufficient evidence – a full scale nuclear exchange is unlikely (<1%) to cause human extinction.

If I wanted to hone in my probability further the post helpfully supplies further reading which is a great feature.

The main subject where I would have liked to see more detail is what I see as the crux of the matter with climate change – given extremely large temperature changes how likely is humanity to go extinct? The arguments in the post itself wouldn’t have been enough for me – it was only reading the Luke Oman interview that convinced me.

Overall I think the post is strong and think it is a good candidate for the 2020 review.

This post feels quite important from a global priorities standpoint. Nuclear war mitigation might have been one of the top priorities for humanity (and to be clear it’s still plausibly quite important). But given that the longtermist community has limited resources, it matters a lot whether something falls in the top 5-10 priorities.

A lot of people ask “Why is there so much focus on AI in the longtermist community? What about other x-risks like nuclear?”. And I think it’s an important, counterintuitive answer that nuclear war probably isn’t an x-risk.

Like Jeff and Bucky, I still think it’s worth someone following up and investigating the phenomenon here in more detail. It’s disappointing that humanity hasn’t studied this problem in as much depth as we could have.