The latest AI development is: AI achieves human level in (blitz 5-minute-turn) full-communication anonymous online Diplomacy (paper). Why not?

I mean, aside from the obvious.

A take I saw multiple times was that AI labs, or at least Meta, were intentionally going for the scariest possible thing, which is why you create the torment nexus, or in this case teach the AI to play Diplomacy. If you had to pick a game to sound scary, you’d definitely pick Diplomacy.

The universal expectations for AI breakthroughs like this are:

The particular breakthrough was not expected, and is scary. The techniques used worked better than we expected, which is scary.

The details of the breakthrough involve someone figuring out why this particular problem configuration was easier to solve than you would expect relative to other problems and configurations, and thus makes it less scary.

We find that those details matter a lot for success, and that close variants would not be so easy. Other times we will find that those details allowed those creating the new thing to skip non-trivial but highly doable steps, that they could go back and do if necessary.

That is all exactly what we find here.

The actual AI, as I understand it, is a combination of a language model and a strategic engine.

The strategic engine, as I evaluated it based on a sample game with six bots and a human, is mediocre at tactics and lousy at strategy. Humans are bad at tactics (and often strategy) in games and Diplomacy is no exception. Diplomacy’s tactics a good match for a AI. Anticipating other players proved harder. The whole thing feels like it is ‘missing a step.’

What Makes the AI Good?

Where does the AI’s advantage come from? From my reading, which comes largely from the sample game in this video, it comes from the particulars of the format, and not making some common and costly mistakes humans make. In particular:

AI writes relatively long, detailed and explanatory communications to others.

AI does not signal its intentions via failing to communicate with its victims.

AI understands that the game ends after 1908 and modifies accordingly.

AI keeps a close eye on strategic balance in order to maximize win percentage.

AI uses its anonymity and one-shot nature to not retaliate after backstabs.

AI knows what humans are like. Humans were not adjusted to bot behaviors.

When people say the AI ‘solved’ Diplomacy, it really really didn’t. What it did, which is still impressive, is get a handle on the basics of Diplomacy, in this particular context where bots cannot be identified and are in the minority, and in particular where message detail is sufficiently limited that it can use an LLM to be able to communicate with humans reasonably and not be identified.

If this program entered the world championships, with full length turns, I would not expect it to do well in its current form, although I would not be shocked if further efforts could fix this (or if they proved surprisingly tricky).

Interestingly, this AI is programmed not to mislead the player on purpose, although it will absolutely go back on its word if it feels like it. This is closer to correct than most players think but a huge weakness in key moments and is highly exploitable if someone knows this and is willing and able to ‘check in’ every turn.

The AI is thus heavily optimized for exactly the world in which it succeeded.

Five minute turns limit human ability to think, plan and talk, whereas for a computer five minutes is an eternity. Longer time favors humans.

Anonymity of bots prevents exploitation of their weaknesses if you can’t confidently identify who they are, and the time limit kept most players too busy to try and confidently figure this out. They also hadn’t had time to learn how the bots functioned and what to expect, even when they did ID them.

One-shot nature of games allows players to ignore their reputations and changes the game theory, in ways that are not natural for humans.

Limited time frame limits punishment for AI’s inability to think about longer term multi-polar dynamics, including psychological factors and game theoretically strange endgame decisions.

Limited time frame means game ends abruptly in 1908 (game begins in 1901, each year is two movement turns, two retreats and a build) in a way that many players won’t properly backward chain for until rather late, and also a lot of players will psychologically be unable to ignore the longer term implications even though they are not scored. In the video I discuss, there is an abrupt ‘oh right game is going to end soon’ inflection point in 1907 by the human.

Rank scoring plus ending after 1908 means it is right to backstab leaders and to do a kind of strange strategy where one is somewhat cooperating with players you are also somewhat fighting, and humans are really bad at this and in my experience they often get mad at you for even trying.

The Core Skill of Online Diplomacy is Talking a Lot

As the video’s narrator explains: The key to getting along with players in online Diplomacy is to be willing to talk to them in detail, and share your thoughts. Each player only has so much time and attention to devote to talking to six other players. Investing in someone is a sign you see a future with them, and letting them know how you are thinking helps them navigate the game overall and your future actions, and makes you a more attractive alliance partner.

Humans also have a strong natural tendency to talk a lot with those they want to ally with, and to be very curt with those they intend to attack or especially backstab (or that they recently attacked or backstabbed). This very much matches my experiences playing online. If a human suddenly starts sending much shorter messages or not talking to you at all, you should assume you are getting stabbed. If you do this to someone else, assume they expect a stabbing. Never take anyone for granted, including those you are about to stab.

This gives the AI a clear opportunity for big advantage. An AI can easily give complex and detailed answers to all six opponents at the same time, for the entire game, in a way a human cannot. That gives them a huge edge. Combine that with humans being relatively bad at Diplomacy tactics (and oh my, they’re quite bad), plus the bots being hidden and thus able to play for their best interests after being stabbed without everyone else knowing this and thus stabbing them, and the dynamics of what actually scores points in a blitz game being counter-intuitive, and the AI has some pretty big edges to exploit.

The five minute turns clearly work to the AI’s advantage. The AI essentially suffers not at all from the time pressure, whereas five minutes is very little time for a human to think. I expect AI performance to degrade relative to humans with longer negotiation periods.

Lessons From the Sample Game

The sample game is great, featuring the player written about here. If you are familiar with Diplomacy or otherwise want more color, I recommend watching the video.

The human player is Russia. He gets himself into big trouble early on by making two key mistakes. He gets out of that trouble because the AI is not good at anticipating certain decisions, a key backstab happens exactly when needed, the player wins a key coin flip decision, and he shifts his strategy into exploiting the tendencies of the bots.

The first big mistake he makes is not committing a third unit to the north. Everything about the situation and his strategy screams to put a third unit in the north, at least an army and ideally a fleet, because the south does not require an additional commitment or does the additional commitment open up opportunity. Instead, without a third northern unit, Russia has nowhere to expand for a long time.

The second big mistake was violating his DMZ agreement with Austria by moving into Galicia. He did this because the AI failed to respond to him during the turn in question, and he was worried this indicated he was about to get stabbed, despite the stab not making a ton of tactical sense. Breaking the agreement with Austria led to a war that was almost fatal (or at least probably did, there’s some chance Austria does it anyway), without any prospect of things going well for Russia at any point.

Against a human, would this play have been reasonable? That depends on how reliable an indicator is radio silence, and how likely a human would be to buy it as an excuse. Against an AI, it does not make sense. The AI has no reason to not talk at all in this spot, regardless of its intentions. So it is strange that it did not respond here, it seems like a rather painful bug.

The cavalry saves us. Italy stabs Austria, while France moves against England.

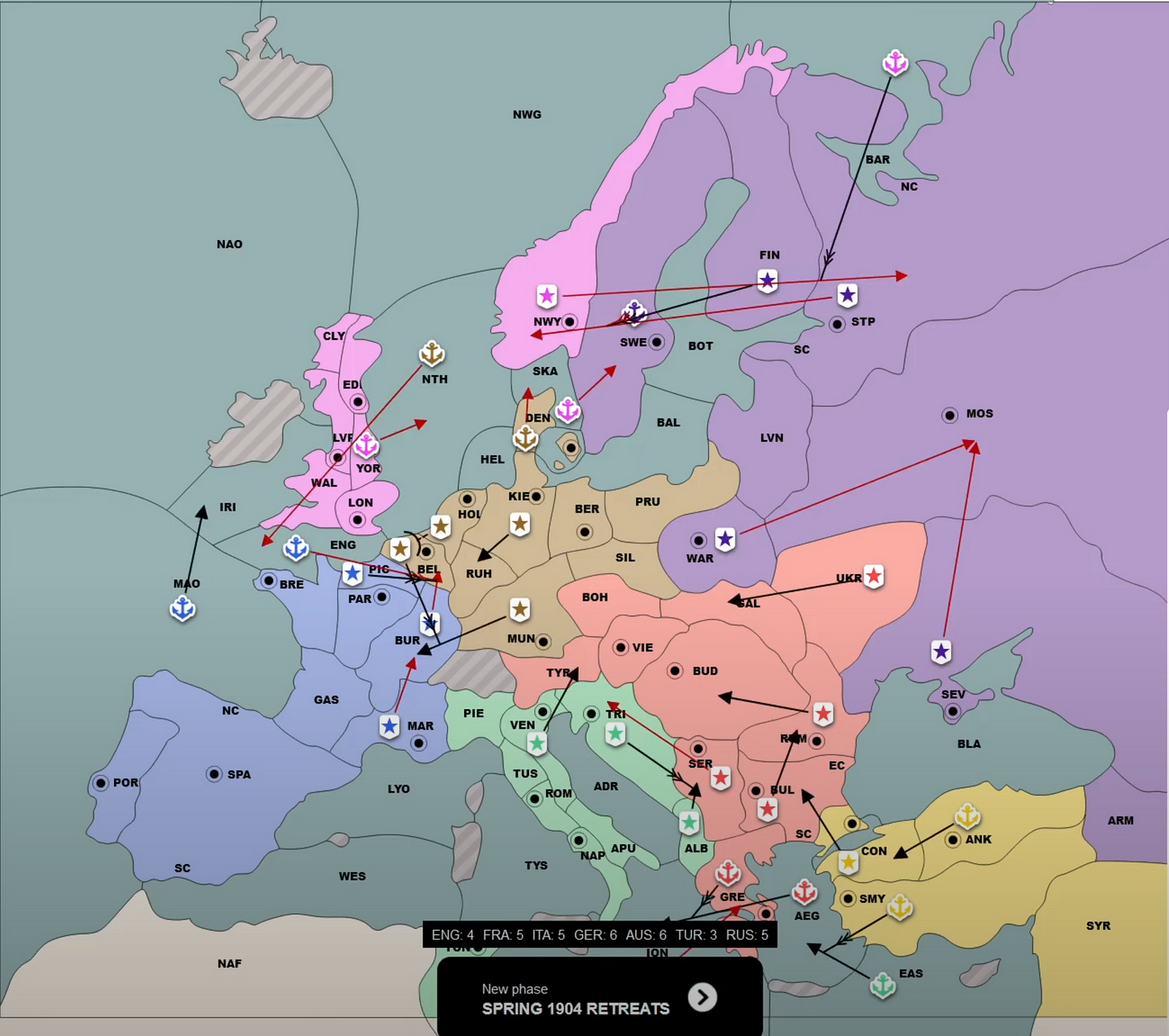

Here is a tactical snapshot. I hate France’s tactical play, both its actual plays and the communications with Russia that are based on its tactics, dating back to at least 1903. The move here to Irish Sea needs to be accompanied by a convoy of Picardy into London or Wales, fighting for Belgium here is silly. Italy does reasonable things. Austria being in Rumania and Ukraine is an existential threat, luckily Austria chooses a retreat here that makes little sense. Once you have Bulgaria against Turkey, you really don’t want to give it up. Austria also lost three or so distinct guessing games here on the same turn. Finally I would note that Italy is surprisingly willing to lose the Ionian Sea to pick up the Aegean, and that if I am Turkey here there is zero chance I am moving Ankara anywhere but Black Sea.

My sense is also that the AI ‘plays it safe’ and does what it thinks is ‘natural’ more often than is game theory optimal. This is confirmed by an author of the paper here, along with other similar observations. The AI assumes it can ‘get away with’ everything because on the internet no one knows you are a bot or what you are up to, and makes decisions accordingly. A huge edge if you get away with it. A huge weakness if you do not.

Then again, Diplomacy players are weird, myself included. There is almost always a tactical way to punish an aggressive ‘natural’ or ‘correct’ play if you are willing to get punished hard by other moves, such as if Germany were to try to sneak into Picardy (PIC) here. So any given decision could be one mixing up one’s play, so my evaluations are more based on the whole of the eight years of play by six players.

The turn above, Spring 1904, is about where Russia pivots from acting like it is playing a normal full game against humans to understanding it is playing an eight-year game for rank order against bots, and he starts asking ‘what would a bot do?’ Things turn around quite a bit after that. His only slip beyond that is at about 42:00 when he worries he will ‘annoy Austria’ in a way that shouldn’t (and didn’t) apply to a bot.

The big exploit of the bots is simple. A bot is not going to retaliate later in the game for a backstab earlier in the game, or at least will retaliate far less. As things shift into the endgame, taking whatever tactical advantages present themselves becomes more and more attractive as an option. Bots will sometimes talk about ‘throwing their centers’ to another player as retaliation, or otherwise punishing an attacker or backstabber, but you know it is mostly talk.

If you play Diplomacy using pure Causal Decision Theory without credible precommitments, and it is a one-shot fully anonymous game, that can work. When you are identifiable (or even worse if someone can see your source code, as they could in a lot of MIRI or other old-school LW thought experiments), you are going to have a bad time.

Diplomatic Decision Theory

The central decision theory question of Diplomacy is how one should respond when stabbed, and what this says about how one should act before one is stabbed.

Responses run the whole range from shrugging it off to devoting the rest of one’s life to revenge. There is a reason people say Diplomacy ruins friendships. Reasonable people max out at ‘spend the rest of the game ensuring you lose’ and being less inclined to trust you in future games, but a lot of what keeps human systems working is that you never know for sure how far things might go.

When deciding whether to attack someone, a key consideration is how they are likely to react. If they are going to go kamikaze on you, you need to ensure you can handle that. If they are going to mostly shrug it off, even let you use your newly strong position to drive a better bargain, then it is open season whenever you have a tactical opening, and then there is everything in between.

The correct solution in a fully one-shot anonymous game, if you can pull it off, is obviously to give people the impression you will strongly retaliate, then to not follow through on that under most circumstances. Humans, of course, have a hard time pulling this off.

Bots also have a hard time pulling this off in a credible way, for different reasons. The bots here mostly were free riders. Humans did not know what they were dealing with. So they gave bots an appropriately broad range of potential reactions. Then the bots got the benefits of not spending their resources on punishment. Once humans did know what they were dealing with, and adjusted, things wouldn’t go so well there. If there were a variety of bots competing at that point, bots would have a hell of a time trying to represent that they would actually retaliate ‘properly.’

Thus, the ‘irrational’ flaws in humans grant them a distinct advantage in the default case, where identity is broadly (partially, at least) known and behaviors have a chance to adjust to what information is available.

AIs so far have essentially ‘gotten away with’ using Causal Decision Theory in these spots, despite its extreme vulnerability to exploitation. This contrasts with many much ‘dumber’ AIs of the past, such as those for Civilization, which were hardcoded with extreme retaliation functions that solve these issues, albeit at what could be a steep price. I wonder what will happen here with, for example, self-driving cars. If AIs are going to be operating in the real world more and more, where similar situations arise, they are going to have to get a better decision theory, or things are going to go very badly for them and also for us.

In this sense, the Hard Problem of Diplomacy has not yet been touched.

Overall Takeaways and Conclusion

The actual results are a mixed bag of things that were surprisingly hard versus surprisingly easy. The easy was largely in ways that came down to how Meta was able to define the problem space. Communications generic and simple and quick enough to easily imitate and even surpass, no reputational or decision theoretic considerations, you can respond to existing metagame without it responding to you. Good times. The hard was in the tactical and strategic engines being lousy (relative to what I would have expected), which is more about Meta not caring or being skilled enough to make a better one rather than it being impossible.

Gwern notes that in June 2020 that Diplomacy AIs were a case of ‘the best NNs can’t even beat humans at a simplified Diplomacy shorn of all communication and negotiation and manipulation and deception aspects.’ I think this is selling the deceptive aspects of no-press (e.g. no communication) Diplomacy short, although it highlights that NNs have a terrible time anticipating human reactions in multiplayer settings, as well. Mostly it seems to me like a case of the people involved not trying all that hard, and in particular not being willing to do a bunch of kludges.

This blog post from Gary Marcus and Ernest Davis gives the perspective that this shows that Ai is not primarily about scaling, offering additional details on how Cicero works. There were a lot of distinct moving pieces that were deliberate human designs. This contrasts with Gwern’s claim that the scaling hypothesis predicted Diplomacy would fall whereas researchers working on the problem didn’t.

I think I come down more on Marcus’ side here in terms of how to update in response to the information. How it was done, in context, seems more important than who claimed it would get done how fast.

I do not get any points for predicting this would happen, since I did not think about the question in advance or make any predictions. It is impossible to go back and confidently say ‘I would have made the right prediction here’ after already knowing the answer. My guess is that if you’d asked, in the abstract, about Diplomacy in general, I would have said it was going to be hard, however if you’d told me the details of how these games were played I would have been much less skeptical.

I do know that I was somewhat confused how hard no-press Diplomacy was proving to be in previous attempts, or at least took it more as evidence no one was trying all that hard relative to how hard they tried at other problems.

I also note that there wasn’t much discussion that I saw of 2-player Diplomacy variations, of which there are several interesting ones, as a way of distinguishing between simultaneous play being difficult versus other aspects. Are Diplomacy actually surprisingly difficult? This would tell us. Perhaps I simply missed it.

Gwern’s conclusion in the comments of this post is that the main update from the Diplomacy AI is that Meta bothered to make a Diplomacy AI. This seems right to me, with the note that it should update us towards Meta being even more of a bad actor than we previously assumed. Also the note that previously Diplomacy had seemed to be proving surprisingly hard in some aspects, and that seems to have largely gone away now, so the update is indeed in the ‘somewhat scarier’ direction on net. Gwern then offers background and timeline considerations from the scaling hypothesis perspective.

My big picture takeaway is that I notice I did not on net update much on this news, in any direction, as nothing was too shocking and the surprises often cancelled out.

It’s worth noticing that, if a future AGI has taken a treacherous turn, it has that same advantage, but moreso: Not only would it be able to carry on simultaneous complex conversations with six key people at the same time, it would likely be able to scale that all the way to simultaneous conversations with every living human at the same time. Or at least every human that plausibly-matters, if compute is still a bottleneck.

for comparison, youtube recommender

Now I want to see my youtube recommender provide text dialogue to convince me that I really do want to watch what it’s selected for me.

“it would be funny if things started to go bad the way we’re worried they will”

While I don’t think anyone aware of AI alignment issues should really update a lot because of Cicero, I’ve found this particular piece of news to be quite effective at making unaware people update toward “AI is scary”.

For me the scary part was Meta’s willingness to do things that are minimally/arguably torment-nexusy and then put it in PR language like “cooperation” and actually with a straight face sweep the deceptive capability under the rug.

This is different from believing that the deceptive capability in question is on it’s own dangerous or surprising.

My update from cicero is almost entirely on the social reality level: I now more strongly than before believe that in the social reality, rationalization for torment-nexus-ing will be extremely viable and accessible to careless actors.

(that said, I think I may have forecasted 30-45% chance of full-press diplomacy success if you had asked me a few weeks ago, so maybe I’m not that unsurprised on the technical level)

I’m a bit puzzled by these reactions. In a sense yes, this is technically teaching an AI to deceive humans… but in a super-limited context that doesn’t really generalize even to other versions of Diplomacy, let alone real life. To me, this is in principle teaching an AI to deceive, but only in a similar sense as having an AI in Civilization sometimes make a die roll to attack you despite having signed a peace treaty. (Analogous to Cicero sometimes attacks you despite having said that it won’t.) It’s a deception so removed from anything that’s relevant for real life, it makes little sense to even call it deception.

I interpret references to things like torment nexuses as implying that Meta knew this to be a bad idea and intentionally chose to go against the social consensus. But I think that’s a social consensus that requires a belief in very short timelines? As in, it requires you to think that we’re a very short way from AGI. In that case, anything that’s done with current-day AI may affect how AGI is developed, so this kind of a project actually has some real chance of conferring AGIs with the capabilities for deception.

But if you don’t believe in very short timelines (something on the order of 5 years or something), then the reasonable default assumption seems to be that this was a fun project done for the technical challenge but probably won’t affect future AGIs one way or the other. Because any genuine ability to deceive that AGIs could have and that would work in the real world would be connected to some more powerful social reasoning ability than this kind of language model tinkering.

Then if Meta doesn’t believe in very short timelines, then there’s no reason to attribute defection/”torment-nexus-ing” to Meta, since they didn’t do anything that could cause damage. They’re not doing a thing that everyone has warned about and said is a bad idea, they’re just doing a cute little toy. And my understanding is that Meta’s staff in general doesn’t believe in very short timelines.

My reaction has nothing to do with “allowing AI to deceive” and everything with “this is a striking example of AI reaching better than average human level at a game that integrates many different core capacities of general intelligences such has natural language, cooperation, bargaining, planning, etc.

Or too put it an other way : for the profane it is easy to think of GPT-3 or deepL or Dall-e as tools, but Cicero will feels more agentic to them.

This piece of news is the most depressing thing I’ve seen in AI since… I don’t know, ever? It’s not like the algorithms for doing this weren’t lying around already. The depressing thing for me is that it was promoted as something to be proud of, with no regard for the framing implication that cooperative discourse exists primarily in service of forming alliances to exterminate enemies.

I’ve searched my memory for the past day or so, and I just wanted to confirm that the “ever” part of my previous message was not a hot take or exaggeration.

I’m not sure what to do about this. I am mulling.

My intuition is having a really hard time being worried about this because… I’m not sure exactly why… in real life, diplomacy occurs in an ongoing long-term game, and it seems to my intuition that the key question is how to win the infinite game by preventing wins of short term destructive games like, well, diplomacy. The fact that a cooperative AI appears to be the best strategy when intending to win the destructive game seems really promising to me, because to me that says that even when playing a game that forces destructive behavior, you still want to play cooperative if the game is sufficiently realistic. The difficult part is forging those alliances in a way that allows making the coprotection alliances broad and durable enough to reach all the way up to planetary and all the way down to cellular; but isn’t this still a promising success of cooperative gameplay?

Maybe I’m missing something. I’m curious why this in particular is so bad—my world model barely updated in response to this paper, I already had cached from a now-deleted Perun gaming video (“Dominions 5 Strategy: Diplomacy Concepts (Featuring Crusader Kings 2)”) that cooperative gameplay is an unreasonably effective strategy in sufficiently realistic games, so seeing an AI discover that doesn’t really change my model of real life diplomacy, or of AI capabilities, or of facebook’s posture.

Seems like we have exactly the same challenge we had before—we need to demonstrate a path out of the destructive game for the planet. How do you quit destructive!diplomacy and play constructive!diplomacy?

I used to think that the first box breaking AI would be a general superintelligence that deduced how to break out of boxes from first principles. Which of course turns the universe into paperclips.

I have updated substantially towards the building of an AI hardcoded and trained specifically to break out of boxes. Which leads to the interesting possibility of an AI that breaks out of it’s box, and then sits their going “now what?”.

Like suppose an AI was trained to be really good at hacking its code from place to place. It massively bungs up the internet. It can’t make nanotech, because nanotech wasn’t in it’s training dataset. Its an AI virus that only knows hacking.

So this is a substantial update in favor of the “AI warning shot”. An AI disaster big enough to cause problems, and small enough not to kill everyone. Of course, all it’s warning against is being a total idiot. But it does plausibly mean humanity will have some experience with AI’s that break out of boxes before superintelligence.

After market close on 10/26/2022, Meta guided an increase in annual capex of ~$4B (from 32-33 for 2022 to 34-39 for 2023), “with our investment in AI driving all of that growth”. NVDA shot up 4% afterhours on this news. (Before you get too alarmed, I read somewhere that most of that is going towards running ML on videos, which is apparently very computationally expensive, in order to improve recommendations, in order to compete with TikTok. But one could imagine all that hardware being repurposed for something else down the line. Plus, maybe it’s not a great idea (for us humans, collectively) to train even narrow AIs to manipulate humans?)

How much do you expect Meta to make progress on cutting edge systems towards AGI vs. focusing on product-improving models like recommendation systems that don’t necessarily advance the danger of agentic, generally intelligent AI?

My impression earlier this year was that several important people had left FAIR, and then FAIR and all other AI research groups were subsumed into product teams. See https://ai.facebook.com/blog/building-with-ai-across-all-of-meta/. I thought this would mean deprioritizing fundamental research breakthroughs and focusing instead on less cutting edge improvements to their advertising or recommendation or content moderation systems.

But Meta AI has made plenty of important research contributions since then: Diplomacy, their video generator, open sourcing OPT and their scientific knowledge bot. Their rate of research progress doesn’t seem to be slowing, and might even be increasing. How do you expect Meta to prioritize fundamental research vs. product going forwards?

Zuckerberg has made a huge bet on VR/”The Metaverse”, to the tune of multiple times the cost of the Apollo Program. The business world doesn’t seem to like this bet, people are not bullish on VR but are very bullish on AI. So the pressure is on Mark to pivot to AI, but also to pivot to anything that is productizable.

Spot check: the largest amount I’ve seen stated for the Metaverse cost is $36 billion, and the Apollo Program was around $25 billion. Taking into account inflation makes the Apollo Program around 5 times more expensive than the Metaverse. Still, I had no idea that the Metaverse was even on a similar order of magnitude!

The $36b number appeared to be extremely bogus when I looked into it the other day after seeing it on Twitter. I couldn’t believe it was that large—even FB doesn’t have that much money to burn each year on just one thing like Metaverse—and figured it had to be something like ‘all Metaverse expenditures to date’ or something else.

It was given without a source in the tweet I was looking at & here. So where does this ‘$36b’ come from? It appears to first actually be FB’s total ‘capex’ reported in some earnings call or filing, which means that it’s covering all the ‘capital expenditures’ which FB makes buying assets by building datacenters or underseas fiberoptics cables; $36b seems like a pretty reasonable number for such a total for one of the largest tech companies in the world which is doing things like cables to Africa, so nothing odd about it. Techcrunch:

Then second, if you wonder what it means that capex doesn’t “strictly include” Metaverse “but is mostly [something else]”, and ask how much of that is ‘Metaverse’ as an upper bound, apparently the answer is ′ as low as $0′, because R&D is defined by the US GAAP financial accounting standard to not be ‘capex’ but a different category altogether, ‘opex’: it’s treated as an operating expense you incur, not as purchasing an asset. (Many argue that R&D is in fact more like ‘buying an asset’ than ‘spending money on operating normally’ and should be under ‘capex’ rather than ‘opex’ - but AFAICT, in the numbers FB is reporting, it would not be.) So “$36b” is not only not just the Metaverse expenses, it’s none of the Metaverse expenses by definition.

(The actual Metaverse number is something like $10b/year, IIRC. Which is pretty staggering on its own—as more than one person has asked, where is it all going? - but a lot smaller.)

Thank you for this. I was going by statistics shared in a recent episode of the All-In Podcast, and I took those stats for granted.

Does it? In the game you link it seems like the bot doesn’t act accordingly in the last move phase. Turkey misses a chance to grab Rumania, Germany misses a chance to grab London, and I think France misses something as well.

This confirms the suspicions I had upon hearing the news: the diplomacy AI falls in a similar category than the Starcraft II AI (AlphaStar) we had a while back.

“Robot beats humans in a race.” Turns out the robot has 4 wheels and an internal combustion engine.

I think these comparisons of “yes, the AI is better than the vast majority of humans at X, but it doesn’t really count, because . . .” miss the point that the danger lies not in the superiority of AI in a fair-as-judged-by-humans-ex-post-facto contest, but in its superiority at all.

A point could be made that there is no real-world analog of contests that are biased in favor of an AI the way this kind of Diplomacy is, but how sure can we be about that?

I agree, and I don’t use this argument regarding arbitrary AI achievements.

But it’s very relevant when capabilities completely orthogonal to the AI are being sold as AI. The Starcraft example is more egregious, because AlphaStar had a different kind of access to the game state than a human has, which was claimed to be “equivalent” by the deepmind team. This resulted in extremely fine-grained control of units that the game was not designed around. Starcraft is partially a sport, i.e., a game of dexterity, concentration, and endurance. It’s unsurprising that a machine beats a human at that.

If you (generic you) are going to make an argument about how speed of execution, parallel communication and so on are game changers (specially in an increasingly online, API accessible world), then make that argument. But don’t dress it up with the supposed intelligence of the agent in question.

I mean, it’s unsurprising now, but before that series of matches where AlphaStar won, it was impossible.

When AlphaStar is capped by human ability and data availability, it’s still better than 99.8% of players, unless I’m missing something, so even if all a posteriori revealed non-intelligence-related advantages are taken away, it looks like there is still some extremely significant Starcraft-specialized kind of intelligence at play.

(ep stat: it’s hard to model my past beliefs accurately, but this is how I remember it)

Maybe for you. But anyone who has actually played starcraft knows that it is a game that is (1) heavily dexterity capped, and (2) intense enough that you barely have time to think strategically. It’s all snap decisions and executing pre-planned builds and responses.

I’m not saying it’s easy to build a system that plays this game well. But neither is it paradigm-changing to learn that such a thing was achieved, when we had just had the news of alphago beating top human players. I do remember being somewhat skeptical of these systems working for RTS games, because the action space is huge, so it’s very hard to even write down a coherent menu of possible actions. I still don’t really understand how this is achieved.

I haven’t looked into this in detail, so assuming the characterization in the article is accurate, this is indeed significant progress. But the 99.8% number is heavily misleading. The system was tuned to have an effective APM of 268, that’s probably top 5% of human players. Even higher if we assume that the AI never misclicks, and never misses any information that it sees. The latter implies 1-frame reaction times to scouting anything of strategic significance, which is a huge deal.

I remember that now—it wasn’t surprising for me, but I thought nobody else expected it.

I mean, it has to be at the top level—otherwise, it would artificially handicap itself in games against the best players (and then we wouldn’t know if it lost because of its Starcraft intelligence, or because of its lower agility). (Edit: Actually, I think it would ideally be matched to the APM of the other player.)

This is a good point. On the other hand, this is just a general feature of problems in the physical world (that humans make mistakes and are slow while computers don’t make the same kind of mistakes and are extra fast), so this seems to generalize to being a threat in general.

(In this specific case, I think the AI can miss some information it sees by it being lost somewhere between the input and the output layer, and the reaction time is between the input and the computation of the output, so it’s probably greater than one frame(?))

On the strategy engine paired with NLP: I wonder how far we could get if the strategic engine was actually just a constructed series of murphyjitsu prompts for the NLP to complete, and then it tries to make decisions as dissimilar to the completed prompts as possible.

My guess is that murphyjitsu about other players would be simpler than situations on the game map in terms of beating humans, but that “solving Diplomacy” would probably begin with situations on the game map because that is clearly quantifiable and quantification of the player version would route through situations anyway.

Post summary (feel free to suggest edits!):

The Diplomacy AI got a handle on the basics of the game, but didn’t ‘solve it’. It mainly does well due to avoiding common mistakes like eg. failing to communicate with victims (thus signaling intention), or forgetting the game ends after the year 1908. It also benefits from anonymity, one-shot games, short round limits etc.

Some things were easier than expected eg. defining the problem space, communications generic and simple and quick enough to easily imitate and even surpass humans, no reputational or decision theoretic considerations, you can respond to existing metagame without it responding to you. Others were harder eg. tactical and strategic engines being lousy (relative to what the author would have expected).

Overall the author did not on net update much on the Diplomacy AI news, in any direction, as nothing was too shocking and the surprises often canceled out.

(If you’d like to see more summaries of top EA and LW forum posts, check out the Weekly Summaries series.)

Disclaimer: I never played diplomacy.

I think this is wrong—I don’t think that’s Andrew Goff in that video.

Hmm, it seems more likely to me that the main reason they opted for Blitz Diplomacy was not that humans benefit more than the AI from extra time, not that it prevents humans from identifying the AI, but that the dialogue model, like many chat bots (I might’ve said all, but then ChatGPT arrived), couldn’t keep up a coherent conversation for longer than that. I’m not very confident in this, though, and I do think the other factors matter a bit too, but maybe not as much.

This seems wrong to me. Bakhtin (2021) achieved superhuman performance in 2-player No-Press Diplomacy. Also, the guy in the video you link calls, in another video, an earlier model (playing 7-player Gunboat Diplomacy) “”exceptionally strong tactically”; I see no reason why CICERO should be much worse (Gunboat Diplomacy isn’t that different from Blitz, I think).

So, in summary, current gen AI continues to be better at reaching small goals (win this game, wriite a paragraph) than the average human attempting those goals, but still lacks the ability to switch between disparate activities, and doesn’t reach the level of a human expert once the playing field gets more complicated than Go or heads-up Poker?