[Crosspost] On Hreha On Behavioral Economics

[crossposted from Astral Codex Ten]

Jason Hreha’s article on The Death Of Behavioral Economics has been going around lately, after an experiment by behavioral econ guru Dan Ariely was discovered to be fraudulent. The article argues that this is the tip of the iceberg—looking back on the last few years of replication crisis, behavioral economics has been undermined almost to the point of irrelevance.

The article itself mostly just urges behavioral economists to do better, which is always good advice for everyone. But as usual, it’s the inflammatory title that’s gone viral. I think a strong interpretation of behavioral economics as dead or debunked is unjustified.

I.

My medical school had final exams made of true-false questions, with an option to answer “don’t know”. They were scored like so: if you got it right, +1 point; wrong, −0.5 points; don’t know, 0. You can easily confirm that it’s always worth guessing even if you genuinely don’t know the answer (+0.25 points on average instead of 0). On average people probably had to guess on ~30% of questions (don’t ask; it’s an Irish education system thing), so you could increase your test score 7.5% with the right strategy here.

I knew all this, but it was still really hard to guess. I did it, but I had to fight my natural inclinations. And when I talked about this with friends—smart people, the sort of people who got into medical school! - none of them guessed, and no matter how much I argued with them they refused to start. The average medical student would sell their soul for 7.5% higher grades on standardized tests—but this was a step too far.

This is Behavioral Econ 101 stuff—risk aversion, loss aversion, and prospect theory. If it’s true, the core of behavioral economics is salvageable. There might be some bad studies built on top of that core, but the basic insights are right.

One more example: every time I order food from GrubHub, I get a menu like this:

And every time I order food from UberEats, I get a menu like this:

I find I usually click the third box on both. I want to tip generously, but giving the maximum possible tip seems profligate. Surely the third box is the right compromise.

I recently noticed that this is insane. For a $35 meal, I’m giving GrubHub drivers $3 and UberEats drivers $7 for the same service (or maybe there’s some difference between their services which makes UberEats suggest the higher tip—but if there is, I don’t know about it and it doesn’t affect my decision).

Again, this is Behavioral Economics 101 - in particular, one of the many biases lumped together under menu effects. Instead of being a rational economic actor who values food delivery at a certain price, I’m trying to be a third-box-of-four kind of guy. That means that whoever is in charge of this menu has lots of power over the specific dollar amount I give. Not infinite power—if the third box said $1000 I would notice and refuse. But enough power that “nudging” seems like a fair description.

Nobody believes studies anymore, which is fair. I trust in a salvageable core of behavioral economics and “nudgenomics” because I can feel in my bones that they’re true for me and the people around me.

Let’s move on to Hreha’s article and see if we can square it with my belief in a “salvageable core”.

II. Yechaim’s Historical Detective Story

Hreha writes:

The biggest replication failures relate to the field’s most important idea: loss aversion.

To be honest, this was a finding that I lost faith in well before the most recent revelations (from 2018-2020). Why? Because I’ve run studies looking at its impact in the real world—especially in marketing campaigns.

If you read anything about this body of research, you’ll get the idea that losses are such powerful motivators that they’ll turn otherwise uninterested customers into enthusiastic purchasers.

The truth of the matter is that losses and benefits are equally effective in driving conversion. In fact, in many circumstances, losses are actually *worse* at driving results.

Why?

Because loss-focused messaging often comes across as gimmicky and spammy. It makes you, the advertiser, look desperate. It makes you seem untrustworthy, and trust is the foundation of sales, conversion, and retention.

“So is loss aversion completely bogus?”

Not quite.

It turns out that loss aversion does exist, but only for large losses. This makes sense. We *should* be particularly wary of decisions that can wipe us out. That’s not a so-called “cognitive bias”. It’s not irrational. In fact, it’s completely sensical. If a decision can destroy you and/or your family, it’s sane to be cautious.

“So when did we discover that loss aversion exists only for large losses?”

Well, actually, it looks like Kahneman and Tversky, winners of the Nobel Prize in Economics, knew about this unfortunate fact when they were developing Prospect Theory—their grand theory with loss aversion at its center. Unfortunately, the findings rebutting their view of loss aversion were carefully omitted from their papers, and other findings that went against their model were misrepresented so that they would instead support their pet theory. In short: any data that didn’t fit Prospect Theory was dismissed or distorted.

I don’t know what you’d call this behavior… but it’s not science.

This shady behavior by the two titans of the field was brought to light in a paper published in 2018: “Acceptable Losses: The Debatable Origins of Loss Aversion”.

I encourage you to read the paper. It’s shocking. This line from the abstract sums things up pretty well: ”...the early studies of utility functions have shown that while very large losses are overweighted, smaller losses are often not. In addition, the findings of some of these studies have been systematically misrepresented to reflect loss aversion, though they did not find it.”

When the two biggest scientists in your field are accused of “systemic misrepresentation”, you know you’ve got a serious problem.

Which leads us to another paper, published in 2018, entitled “The Loss of Loss Aversion: Will It Loom Larger Than Its Gain?”.

The paper’s authors did a comprehensive review of the loss aversion literature and came to the following conclusion: “current evidence does not support that losses, on balance, tend to be any more impactful than gains.”

Yikes.

But given the questionable origins of the field, it’s not surprising that its foundational finding is *also* dubious.

If loss aversion can’t be trusted, then no other idea in the field can be trusted.

This argument relies on two papers—Yechaim’s Acceptable Losses and Gal & Rucker’s Loss Of Loss Aversion.

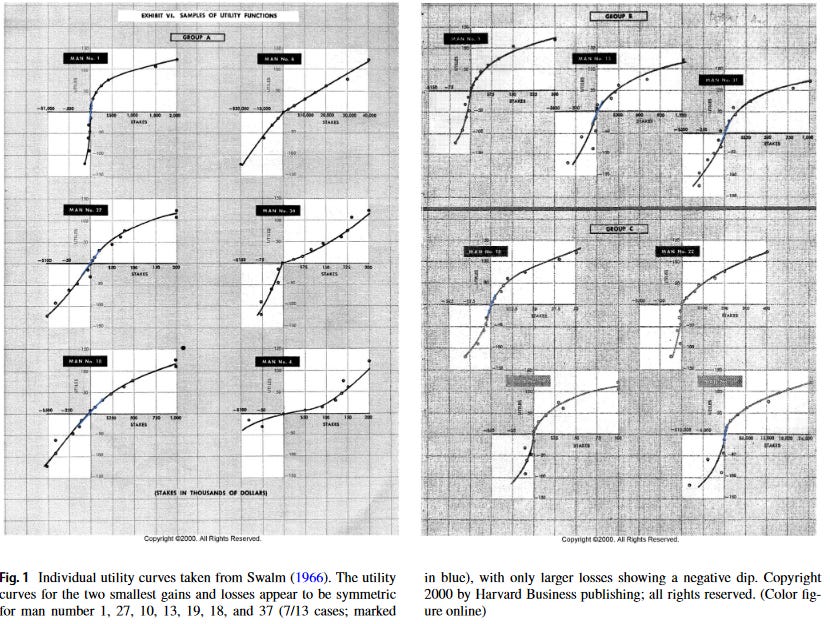

Yechaim’s paper is a historical detective story. It looks at how Kahneman and Tversky first “discovered” and popularized the idea of loss aversion from earlier 1950s and 1960s research. It concludes they did a bad job summarizing this earlier research; looked at carefully, it doesn’t support the strong conclusions they drew.

From one perspective, nobody should care about this. All the 1950s and 1960s research was terrible—one of the most important studies it discusses had n = 7. Since then, we’ve had much more rigorous studies of tens of thousands of people. All that hinges on Yechaim’s paper is whether Kahneman and Tversky were personally bad people.

Hreha thinks they were. He calls their behavior “shady”, “shocking”, and says they “systematically misrepresented findings to support their pet theory…I don’t know what you’d call this behavior… but it’s not science.” Again, nothing important really hinges on this, but I feel like fighting about it, so let’s look deeper anyway.

Here’s how Yechaim summarizes his accusation against K&T:

In addition, the results of several studies seem to have been misrepresented by Fishburn and Kochenberger (1979) and Kahneman and Tversky (1979). Galenter and Pliner (1974) were wrongly cited as showing loss aversion, whereas, in fact, they did not observe an asymmetry in the pleasantness ratings of gains and losses. Likewise, in Green (1963), the results were argued to show loss aversion, even though this study did not involve any losses. In addition, the objective outcomes for some of the participants in Grayson (1960) were transformed by Fishburn and Kochenberger (1979) so as to better support a model assuming different curvatures for gains and losses (see Table 1). Finally, studies showing no loss aversion or suggesting aversion to large losses were not cited in Fishburn and Kochenberger (1979) or in Kahneman and Tversky (1979).

Yechaim bases his argument on three sets of early studies of loss aversion: Galenter and Plinter (1974), Fishburn and Kochenberger’s review (1979) and miscellaneous others.

—Galenter and Plinter— is actually really neat! It explores “cross-modal” perceptions of gains versus losses. That is, if you ask how much a certain loss hurt, people will probably just say something like “I dunno, a little?” and then it will be hard to turn that into a p-value. G&P solve this by making people listen to loud noises, and asking questions like “is the difference between how much loss A and loss B hurt greater or lesser than the difference between the volume of noise 1 and noise 2?” The idea is that the brain uses a bunch of weird non-numerical scales for everything, and we understand its weird-non-numerical scale for noise volume pretty well, and so maybe we can compare it to how people think about gains or losses. I don’t know why people in 1974 were doing anything this complicated instead of inventing the basic theory of loss aversion the way Kahneman and Tversky would five years later, but here we are.

Anyway, Yechaim concludes that this study failed to find loss aversion:

Summing up their findings, Galenter and Pliner (1974) reported as follows: “We now turn to the question of the possible asymmetry of the positive and negative limbs of the utility function. On the basis of intuition and anecdote, one would expect the negative limb of the utility function to decrease more sharply than the positive limb increases… what we have observed if anything is an asymmetry of much less magnitude than would have been expected … the curvature of the function does not change in going from positive to negative” (p. 75). Thus, our search for the historical foundations of loss aversion turns into a dead end on this particular branch: Galenter and Pliner (1974) did not observe such an asymmetry; and their study was quoted erroneously [by Kahneman and Tversky].

I looked for the full text of Galenter and Pliner, but could not find it. I was however able to find the first two pages, including the abstract. The way Galenter and Pliner summarize their own research is:

Cross-modality matching of hypothetical increments of money against loudness recover the previously proposed exponent of the utility function for money within a few percent. Similar cross-modality matching experiments for decrements give a disutility exponent of 0.59, larger than the utility exponent for increments. This disutility exponent was checked by an additional cross-modality matching experiment against the disutility of drinking various concentrations of a bitter solution. The parameter estimated in this fashion was 0.63.

If I understand the bolded part right, the abstract seems to be saying that they did find loss aversion!

I was also able to find the Google Books listing for the book that the study was published in. Its summary is:

Three experiments were conducted in which monetary increments and decrements were matched to either the loudness of a tone or the bitterness of various concentrations of sucrose octa-acetate. An additional experiment involving ratio estimates of monetary loss is also reported. Results confirm that the utility function for both monetary increments and decrements is a power function with exponents less than one. The data further suggest that the exponent of the disutility function is larger than that of the utility function, i.e., the rate of change of ‘unhappiness’ caused by monetary losses is greater than the comparable rate of ‘happiness’ produced by monetary gains. (Author).

Again, the way the book is summarized (apparently by the author) says this study does prove loss aversion.

Without being able to access the full study, I’m not sure what’s going on. Possibly the study found loss aversion, but it was less than expected? Still, I feel like Yechaim should have mentioned this. At the very least, it decreases Kahneman and Tversky’s crime from “lied about a study to support their pet theory” to “credulously believed the authors’ own summary of their results and didn’t dig deeper”. But also, why did the authors believe their study showed loss aversion? Why does Yechaim disagree? Without being able to access the full paper, I’m not sure.

—Green 1963— is the second study that Yechaim accuses K&T of misrepresenting. Here’s how K&T cite this study in their paper:

It is of interest that the main properties ascribed to the value function have been observed in a detailed analysis of von Neumann-Morgenstern utility functions for changes of wealth (Fishburn and Kochenberger [14]). The functions had been obtained from thirty decision makers in various fields of business, in five independent studies [5, 18, 19, 21, 40]. Most utility functions for gains were concave, most functions for losses were convex, and only three individuals exhibited risk aversion for both gains and losses. With a single exception, utility functions were considerably steeper for losses than for gains.

Green 1963 is footnote 19. So K&T don’t even mention it by name. They mention it as one of several studies that a review article called Fishburn and Kochenberger analyzes.

F&K are reviewing a bunch of studies of executives. In each study, a very small number of executives (usually about 5-10 per study) make a hypothetical business decision comparing gains and losses, for example:

Suppose your company is being sued for patent infringement. Your lawyer’s best judgement is that your chances of winning the suit are 50–50; if you win, you will lose nothing, but if you lose, it will cost the company $1,000,000. Your opponent has offered to settle out of court for $200,000. Would you fight or settle?

Then they ask the same question with a bunch of other numbers, and plot implied utility functions for each executive based on the answer.

Green is one of these five studies, and it does superficially find loss aversion. But Fishburn and Kochenberger have done something weird. They argue that “loss” and “gain” aren’t necessarily objective, and usually correspond to “loss relative to some reference frame” (so far, so good). In order to figure out where the reference frame is, they assume that the neutral point is wherever “something unusual happens to the individual’s utility function” (F&K’s words). So they shift the zero point separating losses and gains to wherever the utility function looks most interesting!

After doing this, they find “loss aversion”, ie the utility curve changes its slope at the transition between the loss side and the gain side. But since the transition was deliberately shifted to wherever the utility curve changed slope, “neutral” was defined as “where something unusual happens”, this is almost tautological. It isn’t quite tautological: it’s interesting that most of the utility curves had a sharp transition zone, and it’s interesting that the transition was in the direction of loss-aversion rather than gain-seeking. But it’s tautological enough to be embarrassing.

Still, this is Fishburn and Kochenberger’s embarrassment, not Kahneman and Tversky’s. And Fishburn and Kochenberger included this study in their review alongside several other studies that didn’t do this to the same degree. Kahneman and Tversky just cited the review article. I don’t think citing a review article that does weird things to a study really qualifies as “systematic misrepresentation.”

I guess I’m having a hard time figuring out how angry to be, because everything about Fishburn and Kochenberger is terrible. The average study in F&K includes results from 5-10 executives. But the studies are pretty open about the fact that they interviewed more executives than this, threw away the ones who gave boring answers, and just published results from the interesting ones. Then they moved the axes to wherever looked most interesting. Then they used all this to draw sweeping generalizations about human behavior. Then F&K combined five studies that did this into a review article, without protesting any of it. And then K&T cited the review article, again without protesting.

I have to imagine that all of this was normal by the standards of the time. I have looked up all these people and they were all esteemed scientists in their own day. And I believe the evidence shows K&T summarized F&K faithfully. Shouldn’t they have avoided citing F&K at all? Seems like the same kind of question as “Shouldn’t Pythagoras have published his theorem in a peer-reviewed journal, instead of moving to Italy, starting a cult, and exposing his thigh at the Olympic Games as part of a scheme to convince people he was the god Apollo?” Yes, but the past was a weird place.

As best I can tell, K&T’s citation of G&P agrees with the authors’ own assessment of their results. Their citation of F&K agrees with the reviewers’ assessment and with a charitable reading of most of the studies involved, although those studies are terrible in many ways which are obvious to modern readers. I would urge people interested in the whodunit question to read Kahneman and Tversky’s original paper. I think it paints the picture of a team very interested in their own results and in theory, and citing other people only incidentally, and in accordance with the scientific standards of their time. I don’t feel a need to tar them as “misrepresenters”.

III. Okay, But Is Loss Aversion Real?

Remember, all that is about the personal deficiencies of Kahneman and Tversky. Realistically there have been hundreds of much better studies on loss aversion in the forty years since they wrote their article, so we should be looking at those.

Here Hreha cites Gal & Rucker: The Loss Of Loss Aversion: Will It Loom Larger Than Its Gain? It’s a great 2018 paper that looks at recent evidence and concludes that loss aversion doesn’t exist. But it’s a very specific, interesting type of nonexistence, which I think the Hreha article fails to capture.

G&R are happy to admit that in many, many cases, people behave in loss-averse ways, including most of the classic examples given by Kahneman and Tversky. They just think that this is because of other cognitive biases, not a specific cognitive bias called “loss aversion”. They especially emphasize Status Quo Bias and the Endowment Effect.

Status Quo Bias is where you prefer inaction to action. Suppose you ask someone “Would you bet on a coin flip, where you get $60 if heads and lose $40 if tails?”. They say no. This deviates from rational expectations, and one way to think of this is loss aversion; the prospect of losing $40 feels “bigger” than the prospect of gaining $60. But another way to think of it is as a bias towards inaction—all else being equal, people prefer not to make bets, and you’d need a higher payoff to overcome their inertia.

Endowment Effect is where you value something you already have more than something you don’t. Suppose someone would pay $5 to prevent their coffee mug from being taken away from them, but (in an alternative universe where they lack a coffee mug) would only pay $3 to buy one. You can think of this as loss aversion (the grief of losing a coffee mug feels “bigger” than the joy of gaining one). Or you can think of it as endowment (once you have the coffee mug, it’s yours and you feel like defending it).

These are really fine distinctions; I had to read the section a few times before the difference between loss aversion and endowment effect really made sense to me. Kahneman and Tversky just sort of threw all all this stuff and saw what stuck and didn’t necessarily try super hard to make sure none of the biases they discovered were entirely explainable as combinations of some of the others. G&R think maybe loss aversion is. They do some clever work setting up situations that test loss aversion but not status quo or endowment—for example, offering a risky bet vs. a safer bet. Here they find no evidence for loss aversion as a separate force from the other two biases.

Somewhere in this process, they did an experiment where they gave participants a quarter minted in Denver and asked them if they wanted to exchange it for a quarter minted in Philadelphia. 60% of people very reasonably didn’t care, but another 35% had grown attached to their Denver quarter, with only 5% actively seeking the novelty of Philadelphia. Psychology is weird.

I understand why some people would summarize this paper as “loss aversion doesn’t exist”. But it’s very different from “power posing doesn’t exist” or “stereotype threat doesn’t exist”, where it was found that the effect people were trying to study just didn’t happen, and all the studies saying it did were because of p-hacking or publication bias or something. People are very often averse to losses. This paper just argues that this isn’t caused by a specific “loss aversion” force. It’s caused by other forces which are not exactly loss aversion. We could compare it to centrifugal force in physics: real, but not fundamental.

Also, you can’t use this paper to argue that “behavioral economics is dead”. At best, the paper proves that loss aversion is better explained by other behavioral economic concepts. But you can’t get rid of behavioral econ entirely! The stuff you have to explain is still there! It’s just a question of which parts of behavioral econ you use to explain it.

Complicating this even further is Mrkva et al, Loss Aversion Has Moderators, But Reports Of Its Death Are Greatly Exaggerated (h/t Alex Imas, who has a great Twitter thread about this). This is an even newer paper, 2019, which argues that Gal and Rucker are wrong, and loss aversion does have an independent existence as a real force.

There are many things to like about this paper. Previous criticisms of loss aversion argue that most experiments are performed on undergrads, who are so poor that even small amounts of money might have unusual emotional meaning. Mrkva collects a sample of thousands of millionaires (!) and demonstrates that they show loss aversion for sums of money as small as $20. On the other hand, I’m not sure they’re quite as careful as G&R at ruling out every other possible bias (although I don’t have a great understanding of where the borders between biases are and I can’t say this for sure).

The main point I want to make is that all the scientists in this debate seem smart, thoughtful, and impressive. This isn’t like social priming experiments where one person says a crazy thing, nobody ever replicates it at scale, and as soon as someone tries the whole thing collapses. These have been replicated hundreds of times, with the remaining arguments being complicated semantic and philosophical ones about how to distinguish one theory from a very slightly different theory. If that takes replicating your result on a sample of thousands of millionaires, people will gather a sample of thousands of millionaires and get busy on the replication. Just overall really impressive work. I don’t feel qualified to take a side in the G&R vs. Mkrva debate, but both teams make me really happy that there are smart and careful people considering these questions.

And this is just a drop in the bucket. Alex Imas also links Replicating patterns of prospect theory for decision under risk, which says:

Though substantial evidence supports prospect theory, many presumed canonical theories have drawn scrutiny for recent replication failures. In response, we directly test the original methods in a multinational study (n = 4,098 participants, 19 countries, 13 languages), adjusting only for current and local currencies while requiring all participants to respond to all items. The results replicated for 94% of items, with some attenuation. Twelve of 13 theoretical contrasts replicated, with 100% replication in some countries. Heterogeneity between countries and intra-individual variation highlight meaningful avenues for future theorizing and applications. We conclude that the empirical foundations for prospect theory replicate beyond any reasonable thresholds.

Beyond any reasonable thresholds!

IV. Do Nudges Work? or, How Small Is Small?

Continuing through the Hreha article:

For a number of years, I’ve been beating the anti-nudge drum. Since 2011, I’ve been running behavioral experiments in the wild, and have always been struck by how weak nudges tend to be.

In my experience, nudges usually fail to have *any* recognizable impact at all.

This is supported by a paper that was recently published by a couple of researchers from UC Berkeley. They looked at the results of 126 randomized controlled trials run by two “nudge units” here in the United States.

I want you to guess how large of an impact these nudges had on average...

30%? 20%? 10%? 5%? 3%? 1.5%? 1%? 0%?

If you said 1.5%, you’d be right (the actual number is 1.4%, but if I had written that out you would have chosen it because of its specificity).

According to the academic papers these nudges were based upon, these nudges should have had an average impact of 8.7%. But, as you probably understand by now, behavioral economics is not a particularly trustworthy field.

I actually emailed the authors of this paper, and they thought the ~1% effect size of these interventions was something to be applauded—especially if the intervention was cheap & easy.

Unfortunately, no intervention is truly cheap or easy. Every single intervention requires, at the very minimum, administrative overhead. If you’re going to do something, you need someone (or some system) to implement and keep track of it. If an intervention is only going to get you a 1% improvement, it’s probably not even worth it.

Uber infamously had a team of behavioral economists working on its product, trying to “nudge” people in the right direction.

Relatedly, Uber makes $10 billion in yearly revenue. If they can “nudge” people to spend 1% more, that’s $100 million. That’s not much relative to revenue, but it’s a lot in absolute terms. In particular, it pays the salary of a lot of behavioral economists. If you can hire 10 behavioral economists for $100,000 a year and make $100 million, that’s $99 million in profit.

Or what if you’re a government agency, trying to nudge people to do prosocial things? There are about 90 million eligible Americans who haven’t gotten their COVID vaccine, and although some of them are hard-core conspiracy theorists, others are just lazy or nervous or feel safe already.

(source)

Whoever decided on that grocery gift card scheme was nudging, whether or not they have an economics degree—and apparently they were pretty good at it. If some sort of behavioral econ campaign can convince 1.5% of those 90 million Americans to get their vaccines, that’s 1.4 million more vaccinations and, under reasonable assumptions, maybe a few thousand lives saved.

Hreha says that:

Every single intervention requires, at the very minimum, administrative overhead. If you’re going to do something, you need someone (or some system) to implement and keep track of it. If an intervention is only going to get you a 1% improvement, it’s probably not even worth it.

This depends on scale! 1% of a small number isn’t worth it! 1% of a big number is very worth it, especially if that big number is a number of lives!

A few caveats. First, a small number only matters if it’s real. It’s very easy to get spurious small effects, so much so that any time you see a small effect you should wonder if it’s real. I’m ready to be forgiving here because behavioral economics is so well-replicated and common-sensically true, but I wouldn’t blame anyone who steers clear.

Second, Hreha says:

To be honest, you can probably use your creativity to brainstorm an idea that will get you a 3-4% minimum gain, no behavioral economics “science” required.

Which leads me to the final point I’d like to make: rules and generalizations are overrated.

The reason that fields like behavioral economics are so seductive is because they promise people easy, cookie-cutter solutions to complicated problems.

Figuring out how to increase sales of your product is hard. You need to figure out which variables are responsible for the lackluster interest.

Is the price the issue? Is the product too hard to use? Is the design tacky? Is the sales organization incompetent? Is the refund/return policy lacking? etc.

Exploring these questions can take months (or years) of hard work, and there’s no guarantee that you’ll succeed.

If, however, a behavioral economist tells you that there are nudges that will increase your sales by 10%, 20%, or 30% without much effort on your part...

Whoa. That’s pretty cool. It’s salvation.

Thus, it’s no surprise that governments and companies have spent hundreds of millions of dollars on behavioral “nudge” units.

Unfortunately, as we’ve seen, these nudges are woefully ineffective.

Specific problems require specific solutions. They don’t require boilerplate solutions based on general principles that someone discovered by studying a bunch of 19 year old college students.

However, the social sciences have done a good job of convincing people that general principles are better solutions for problems than creative, situation-specific solutions.

In my experience, creative solutions that are tailor-made for the situation at hand *always* perform better than generic solutions based on one study or another.

Hreha is a professional in this field, so presumably he’s right. Still, compare to medicine. A thoughtful doctor who tailors treatment to a particular patient sounds better (and is better) than one who says “Depression? Take this one all-purpose depression treatment which is the first thing I saw when I typed ‘depression’ into UpToDate”. But you still need medical journals. Having some idea of general-purpose laws is what gives the people making creative solutions something to build upon.

(also, at some point your customers might want to check your creative solution to see whether it actually gives a “3-4% minimum gain, no behavioral economics required”, and that would be at least vaguely study-shaped.)

Third, everyone who said nudging had vast effects is still bad and wrong. Many of them were bad and wrong and making fortunes consulting for companies about how to implement the policies they were claiming were super-powerful. This is suspicious and we should lower our opinion of them accordingly. In a previous discussion of growth mindset, I wrote:

Imagine I claimed our next-door neighbor was a billionaire oil sheik who kept thousands of boxes of gold and diamonds hidden in his basement. Later we meet the neighbor, and he is the manager of a small bookstore and has a salary 10% above the US average… Should we describe this as “we have confirmed the Wealthy Neighbor Hypothesis, though the effect size was smaller than expected”? Or as “I made up a completely crazy story, and in unrelated news there was an irrelevant deviation from literally-zero in the same space”?

All the people talking about oil sheiks deserve to get asked some really uncomfortable questions. And a lot of these will be the most famous researchers—the Dan Arielys of the world—because of course the people who successfully hyped their results a lot are the ones the public knows about.

Still, the neighbor seems like a neat guy, and maybe he’ll give you a job at his bookstore.

V. Conclusion: Musings On The Identifiable Victim Effect

I actually skipped the very beginning of Hreha’s article. I want to come back to it now. It begins:

The last few years have been particularly bad for behavioral economics. A number of frequently cited findings have failed to replicate.

Here are a couple of high profile examples:

The Identifiable Victim Effect (featured in the workbooks I wrote with Dan Ariely and Kristen Berman in 2014)

Priming (featured in Nudge, Cialdini’sbooks, and Kahneman’s Thinking Fast and Slow)

One place you could go with this is to point out that this all seems more like social psych than like behavioral economics. I agree that there’s a thin line at times, but I think these are clearly on the other side of it. It’s weird that this should matter, but if you’re claiming a field stands or falls together, then getting the boundaries of that field right is important.

But more important—what does it mean to say that the Identifiable Victim Effect has “failed to replicate”?

The Identifiable Victim Effect is a thing where people care more about harm done to an identifiable victim (eg “John the cute orphan”) than a broad class of people (eg “inhabitants of Ethiopia”). Hreha’s article doesn’t link to the purported failed replications, but plausibly it’s Hart, Lane, and Chinn: The elusive power of the individual victim: Failure to find a difference in the effectiveness of charitable appeals focused on one compared to many victims. If I understand right, it compared simulated charity ads:

Ad A: A map of the USA. Text describing how millions of single mothers across the country are working hard to support their children, and you should help them.

Ad B: A picture of a woman. Text describing how this is Mary, a single mother who is working hard to support her children, and you should help her.

All subjects were entered into a raffle to win a gift certificate for participating in the study, and they were offered the opportunity to choose to donate some of it to single mothers. Subjects who saw Ad B didn’t donate any more of their gift certificate than those who saw Ad A. This is a good study. I’m mildly surprised by the result, but I don’t see anything wrong with it.

But also: there are several giant murals of George Floyd within walking distance of my house. It sure seems people cared a lot when George Floyd (and Trayvon Martin, and Michael Brown, and…) got victimized. There are lots of statistics, like “US police kill about 1000 people a year, and about 10 of those are black, unarmed, and not in the process of doing anything unsympathetic like charging at the cops”. But somehow those statistics don’t start riots, and George Floyd does. You can publish 100 studies showing how “the Identifiable Victim Effect fails to replicate”, but I will still be convinced that George Floyd’s death affected America more than aggregate statistics about police shootings.

It feels kind of unvirtuous to say this. Isn’t this like saying “I saw homeopathy cure my Uncle Bob with my own eyes, so I don’t care how many high-falutin’ randomized controlled trials say it doesn’t work?” Yeah, kind of. So what do we do?

The usual tactic here is to look for “moderators”, ie factors that make something true in one case but false in others. Maybe identifiable victims are better at provoking outrage, but not at increasing charitable donations. Maybe identifiable victims work better in a social context where different people are talking about and reblogging stories to everyone else, but not in a one-shot laboratory game. Maybe people interpret obvious charity ads as manipulation and deliberately shut down any emotions they produce.

This kind of moderator analysis has gotten some bad press lately, because whenever a replication attempt fails, the original scientist usually says there must be moderators. “Oh, you would have gotten the same results as me, except that I wore a blue shirt while doing the experiment and you wore a red shirt and that changed everything. If only the replication team had been a bit smarter, they would have realized they had to be more careful with clothing color. True replication of my results has never been tried!” I want to make fun of these people, but something like this has to be true with the George Floyd vs. Mary The Single Mother problem.

Maybe the real problem here is that we’ve all gotten paranoid. We hear “identifiable victim effect fails to replicate”, and it brings up this whole package of things—power posing, stereotype threat, Dan Ariely, maybe the whole Identifiable Victim industry is a grift, maybe the data is fraudulent, maybe…

I’m reminded of Gal and Rucker’s study on loss aversion. Hreha summed it up as “loss aversion doesn’t exist”, and I immediately jumped to “Oh, so it doesn’t replicate and the whole field is fraudulent and Daniel Kahneman was a witch?” But actually, this was the completely normal scientific process of noticing a phenomenon, doing some experiments to figure out what caused the phenomenon, and then arguing a bunch about how to interpret them, with new experiments being the tiebreaker. Again, loss aversion is real, but not fundamental, like centrifugal force in physics. The person who discovered centrifugal force wasn’t doing anything wrong, and it wouldn’t be fair to say that his experiments “failed to replicate”. Something we thought was an ontological primitive just turned out to be made of smaller parts, which is the story of science since Democritus.

I recommend Section 3 of Gal & Rucker, which gets into some philosophy of science here, including the difference between normal science and a paradigm shift. Part of paradigm shifting is interpreting old results in a new way. This often involves finding out that things don’t exist (eg the crystal spheres supporting the planets). It’s not that the observation (the planets spin round and round) are wrong, just that the hypothesized structures and forces we drew in as explanations weren’t quite right, and we need different structures and forces instead.

Somewhere there’s an answer to the George Floyd vs. Mary The Single Mother problem. This doesn’t look like “Scientists have proven that a thing called the Identifiable Victim Effect exists and applies in all situations with p < 0.00001”, nor does it look like “this scientist DESTROYS the Identifiable Victim Effect with FACTS and LOGIC”. Probably at the beginning it will look like a lot of annoying stuff about “moderators”, and if we are very lucky in the end it will look like a new paradigm that compresses all of this in an intuitive way and makes it drop-down obvious why these two cases would differ.

“Behavioral economics” as a set of mysteries that need to be explained is as real as it ever was. You didn’t need Kahneman and Tversky to tell you that people sometimes make irrational decisions, and you don’t need me to tell you that people making irrational decisions hasn’t “failed to replicate”.

“Behavioral economics” as the current contingent group of people investigating these mysteries seems overall healthy to me, a few Dan Arielys not withstanding. They seem to be working really hard to replicate their findings and understand where and why they disagree.

“Behavioral economics” as the particular paradigm these people have invented to explain these mysteries seems…well, Thomas Kuhn says you’re not allowed to judge paradigms as good or bad, but Thomas Kuhn was kind of silly. I think it’s better than we had fifty years ago, and hopefully worse than what we’ll have fifty years from now.

Interesting tangent: if we start with the kind of inexploitability arguments typically used to justify utility functions, and modify them to account for agents having internal state, then we get subagents. Rather than inexploitable decision-makers always being equivalent to utility-maximizers, we find that inexploitable decision-makers are equivalent to committees of utility-maximizers where each “committee member” has a veto. (In particular, this model handles markets, which are the ur-example of inexploitability yet turn out not to be equivalent to a single utility maximizer.)

What sort of “biases” would someone expecting a utility-maximizer would find when studying such a subagent-based decision-maker? In other words, how does a subagent-based decision-maker’s decisions differ from a utility-maximizer’s decisions? Mainly, there are cases where the subagent will choose A over B if it already has A, and B over A if it already has B. (Interpretation: there are two subagents, one of which wants A, and one of which wants B. If we already have A, then the A-preferring subagent will veto any offer to switch; if we already have B, then the B-preferring subagent will veto any offer to switch.) In other words: there’s a tendency toward inaction, and toward assigning “more value” to whatever the agent currently has. Status Quo Bias, and Endowment Effect.

And yet, neither of these supposed “biases” is actually exploitable. Such decision-makers can’t be money-pumped.

Out of curiosity, when do you crosspost to LW versus just posting to ACX? I can see that this post is very LW since it’s about biases and thus rationality, but I have to think almost all the readers of LW also read ACX.

Is the discussion in the comments different here? (Certainly the comment interface and threading are way better here.)

What is ACX?

Astral Codex Ten

https://astralcodexten.substack.com/

FKA slatestarcodex.

I’m sorry but I was just so lost by the end of this article. I have no explanation for why Hreha doesn’t know what a UX researcher is or that they professionally do behavorial economics all day including designing nudge-like behavior, like for instance a tip app screen, that nudges you to tip $1 on a $3 coffee.

Btw, Scott mentioned having to read a bunch to figure out the subtle difference between loss aversion and the endowment effect. I attempted a full explainer: https://blog.beeminder.com/loss/