Background Reading: The Real Hufflepuff Sequence Was The Posts We Made Along The Way

This is the fourth post of the Project Hufflepuff sequence. Previous posts:

Who exactly is the Rationality Community? (i.e. who is Project Hufflepuff trying to help)

Epistemic Status: Tries to get away with making nuanced points about social reality by using cute graphics of geometric objects. All models are wrong. Some models are useful.

Traditionally, when nerds try to understand social systems and fix the obvious problems in them, they end up looking something like this:

Social dynamics is hard to understand with your system 2 (i.e. deliberative/logical) brain. There’s a lot of subtle nuances going on, and typically, nerds tend to see the obvious stuff, maybe go one or two levels deeper than the obvious stuff, and miss that it’s in fact 4+ levels deep and it’s happening in realtime faster than you can deliberate. Human brains are pretty good (most of the time) at responding to the nuances intuitively. But in the rationality community, we’ve self-selected for a lot of people who:

Don’t really trust things that they can’t understand fully with their system 2 brain.

Tend not to be as naturally skilled at intuitive mainstream social styles.

Are trying to accomplish things that mainstream social interactions aren’t designed to accomplish (i.e. thinking deeply and clearly on a regular basis).

This post is an overview of essays that rationalist-types have written over the past several years, that I think add up to a “secret sequence” exploring why social dynamics are hard, and why they are important to get right. This may useful both to understand some previous attempts by the rationality community to change social dynamics on purpose, as well as to current endeavors to improve things.

(Note: I occasionally have words in [brackets], where I think original jargon was pointing in a misleading direction and I think it’s worth changing)

To start with, a word of caution:

Armchair sociolology can be harmful [link] - Ozy’s post is pertinent—most essays below fall into the category of “armchair sociology”, and attempts by nerds to understand and articulate social-dynamics that they aren’t actually that good at. Several times when an outsider has looked in at rationalist attempts to understood human interaction they’ve said “Oh my god, this is the blind leading the blind”, and often that seemed to me like a fair assessment.

I think all the essays that follow are useful, and are pointing at something real. But taken individually, they’re kinda like the blind men groping at the elephant, each coming away with the distinct impression an elephant is like a snake, tree, a boulder, depending on which aspect they’re looking at.

[Fake Edit: Ozy informs me that they were specifically warning against amateur sociology and not psychology. I think the idea still roughly applies]

i. Cultural Assumptions of Trust

Guess [Infer] Culture, Ask Culture, and Tell [Reveal] Culture (link)

(by Malcolm Ocean)

Different people have different ways of articulating their needs and asking for help. Different ways of asking require different assumptions of trust. If people are bringing different expectations of trust into an interaction, they may feel that that trust is being violated, which can seem rude, passive aggressive or oppressive.

I’m listing this article, instead of numerous others about Ask/Guess/Tell, because I think: a) Malcolm does a good job of explaining how all the cultures work, and b) I think his presentation of Reveal culture is a good, clearer upgrade for Brienne’s Tell culture, and I’m a bit sad it didn’t seem to make it into the zeitgeist yet.

I also like the suggestion to call Guess Culture “Infer Culture” (implying a bit more about what skills the culture actually emphasizes).

Guess Culture Screens for Trying to Cooperate (link) (Ben Hoffman)

Rationality folk (and more generally, nerds), tend to prefer explicit communication over implicit, and generally see Guess culture as strictly inferior to Ask culture once you’ve learned to assert yourself.

But there is something Guess culture does which Ask culture doesn’t, which is give you evidence of how much people understand you and are trying to cooperate. Guess cultures filters for people who have either invested effort into understanding your culture overall, or people who are good at inferring your own wants.

Sharp Culture and Soft Culture (link) (Sam Rosen)

[WARNING: It turned out lots of people thought this meant something different than what I thought it meant. Some people thought it meant soft culture didn’t involve giving people feedback or criticism at all. I don’t think Soft/Sharp are totally-naturally clusters in the first place, and the distinction I’m interested in (as applies to rationality-culture), is how you give feedback.

(i.e. “Dude, your art sucks. It has no perspective.” vs “oh, cool. Nice colors. For the next drawing, you might try incorporating perspective”, as a simplified example)

Somewhat orthogonal to Infer/Ask/Reveal culture is “Soft” vs “Sharp” culture. Sharp culture tends to have more biting humor, ribbing each other, and criticism. Soft culture tends to value kindness and social harmony more. Sam says that Sharp culture “values honesty more.” Robby Bensinger counters in the comments: “My own experience is that sharp culture makes it more OK to be open about certain things (e.g., anger, disgust, power disparities, disagreements), but less OK to be open about other things (e.g., weakness, pain, fear, loneliness, things that are true but not funny or provocative or badass).”

Handshakes, Hi, and What’s New: What’s Going on With Small Talk? (Ben Hoffman)

Small talk often sounds nonsensical to literally-minded people, but it serves a fairly important function: giving people a structured path to figure out how much time/sympathy/interest they want to give each other. And even when the answer is “not much”, it still is, significantly, nonzero—you regard each other as persons, not faceless strangers.

Personhood [Social Interfaces?] (Kevin Simler)

This essays gets a lot of mixed reactions, much of which I think has to do with its use of the word “Person.” The essay is aimed at explaining how people end up treating each other as persons or nonpersons, without making any kind of judgement about it. This includes noting some things human tend to do that you might consider horrible.

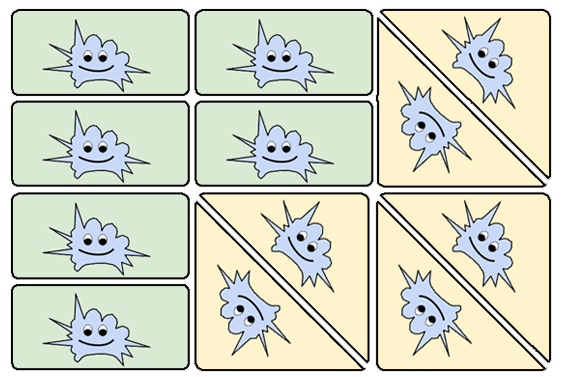

Like many grand theories, I think it overstates it’s case and ignores some places where the explanation breaks down, but I think it points at a useful concept which is summarized by this adorable graphic:

The essay uses the word “personhood”. In the original context, this was useful: it gets at why cultures develop, why it matters whether you’re able to demonstrate reliably, trust, etc. It helps explain outgroups and xenophobia: outsiders do not share your social norms, so you can’t reliably interact with them, and it’s easier to think of them as non-people than try to figure out how to have positive interactions.

But what I’m most interested in is “how can we use this to make it easier for groups with different norms to interact with each other”? And for that, I think using the word “personhood” makes it way more likely to veer into judging each other for having different preferences and communication styles.

What makes a person is… arbitrary, but not fully arbitrary.

Rationalist culture tends to attract people who prefer a particular style of “social interface”, often favoring explicit communication and discussing ideas in extreme detail. There’s a lot of value to those things, but they have some problems:

a) this social interface does NOT mesh well with much of the rest of world (this is a problem if you have any goals that involve the rest of the world)

b) this goal does not uniformly mesh well with all people interested in and valuable to the rationality community.

I don’t actually think it’s possible to develop a set of assumptions that fit everyone’s needs. But I do think it’s possible to develop better tools for navigating different social contexts. I think it may be possible both to tweak sets-of-norms so that they mesh better together, or at least when they bump into each other, there’s greater awareness of what’s happening and people’s default response is “oh, we seem to have different preferences, let’s figure out how

Maybe we can end up with something that looks kinda like this:

Against Being Against or For Tell Culture (Brienne Yudkowsky)

Having said a bunch of things about different cultural interfaces, I think this post by Brienne is really important, and highlights the end goal of all of this.

“Cultures” are a crutch. They are there to help you get your bearings. They’re better than nothing. But they are not a substitute for actually having the skills needed to navigate arbitrary social situations as they come up so you can achieve whatever it is you want to achieve.

To master communication, you can’t just be like, “I prefer Tell Culture, which is better than Guess Culture, so my disabilities in Guess Culture are therefore justified.” Justified shmustified, you’re still missing an arm.

My advice to you—my request of you, even—if you find yourself fueling these debates [about which culture is better], is to (for the love of god) move on. If you’ve already applied cognitive first aid, you’ve created an affordance for further advancement. Using even more tourniquettes doesn’t help.

ii. Game Theory, Recursion, Trust

(or, “Social dynamics are complicated, you are not getting away with the things you think you are getting away with, stop trying to be clever, manipulative, act-utilitarian or naive-consequentialist without actually understanding what is going on”)

Grokking Newcomb’s Problem and Deserving Trust (Andrew Critch)

Critch argues why it is not just “morally wrong”, but an intellectual mistake, to violate someone’s trust (even when you don’t expect any repercussions in the future).

When someone decides whether to trust you (say, giving you a huge opportunity), on the expectation that you’ll refrain from exploiting them, they’ve already run a low-grade simulation of you in their imagination. And the thing is that you don’t know whether you’re in a simulation or not when you make the decision whether to repay them.

Some people argue “but I can tell that I’m a conscious being, and they aren’t a literal super-intelligent AI, they’re just a human. They can’t possibly be simulating me in this high fidelity. I must be real.” This is true. But their simulation of you is not based on your thoughts, it’s based on your actions. It’s really hard to fake.

One way to think about it, not expounded on in the article: Yes, if you pause to think about it you can notice that you’re conscious and probably not being simulated in their imagination. But by the time you notice that, it’s too late. People build up models of each other all the time, based on very subtle cues such as how fast you respond to something. Conscious you knows that you’re conscious. But their decision of whether to trust you was based off the half-second it took for unconscious you to reply to questions like “Hey, do you think you handle Project X while I’m away?”

The best way to convince people you’re trustworthy is to actually be trustworthy.

You May Not Believe In Guess [Infer] Culture But It Believes In You (Scott Alexander)

This is short enough to just include the whole thing:

Consider an “ask culture” where employees consider themselves totally allowed to say “no” without repercussions. The boss would prefer people work unpaid overtime so ey gets more work done without having to pay anything, so ey asks everyone. Most people say no, because they hate unpaid overtime. The only people who agree will be those who really love the company or their job—they end up looking really good. More and more workers realize the value of lying and agreeing to work unpaid overtime so the boss thinks they really love the company. Eventually, the few workers who continue refusing look really bad, like they’re the only ones who aren’t team players, and they grudgingly accept.

Only now the boss notices that the employees hate their jobs and hate the boss. The boss decides to only ask employees if they will work unpaid overtime when it’s absolutely necessary. The ask culture has become a guess culture.

How this applies to friendship is left as an exercise for the reader.

The Social Substrate (Lahwran)

A fairly in depth look into how common knowledge, signaling, newcomb-like problems and recursive modeling of each other interact to produce “regular social interaction.”

I think there’s a lot of interesting stuff here—I’m not sure if it’s exactly accurate but it points in directions that seem useful. But I actually think the most important takeaway is the warning at the beginning:

WARNING: An easy instinct, on learning these things, is to try to become more complicated yourself, to deal with the complicated territory. However, my primary conclusion is “simplify, simplify, simplify”: try to make fewer decisions that depend on other people’s state of mind. You can see more about why and how in the posts in the “Related” section, at the bottom.

When you’re trying to make decisions about people, you’re reading a lot of subtle cues off them to get a sense of how you feel about that. When you [generic person you, not necessarily you in particular] can tell someone is making complex decisions based on game theory and trying to model all of this explicitly, it a) often comes across as a bit off, and b) even if it doesn’t, you still have to invest a lot of cognitive resources figuring out how they are modeling things and whether they are actually doing a good job or missing key insights or subtle cues. The result can be draining, and it can output a general response of “ugh, something about this feels untrustworthy.”

Whereas when people are able to cache this knowledge down into a system-1 level, you’re able to execute a simpler algorithm that looks more like “just try to be a good trustworthy person”, that people can easily read off your facial expression, and which reduces overall cognitive burden.

System 1 and System 2 Morality (Sophie Grouchy)

There’s some confusion over what “moral” means, because there’s two kinds of morality:

System 1 morality is noticing-in-realtime when people need help, or when you’re being an asshole, and then doing something about it.

System 2 morality is when you have a complex problem and a lot of time to think about it.

System 1 moralists will pay back Parfit’s Hitchhiker because doing otherwise would be being a jerk. System 2 moralists invent Timeless [Functional?] decision theory.

You want a lot of people with System 2 morality in the world, trying to fix complex problems. You want people with System 1 morality in your social circle.

The person who wrote this post eventually left the rationality community, in part due to frustration due to people constantly violating small boundaries that seemed pretty obvious (things in the vein of “if you’re going to be 2 hours late, text me so I don’t have to sit around waiting for you.”)

Final Remarks

I want to reiterate—all models are wrong. Some models are useful. The most important takeaway from this is not that any particular one of these perspectives is true, but that social dynamics has a lot of stuff going on that is more complicated than you’re naively imagining, and that this stuff is important enough to put the time into getting right.

- What exactly is the “Rationality Community?” by (9 Apr 2017 0:11 UTC; 65 points)

- A Month’s Worth of Rational Posts—Feedback on my Rationality Feed. by (15 May 2017 14:21 UTC; 21 points)

- 's comment on Reveal Culture by (3 Aug 2020 22:15 UTC; 19 points)

- 's comment on Circling by (19 Feb 2018 6:00 UTC; 6 points)

I would like to register disagreement not with the technical truth value of this statement, but with the overall sentiment that I believe this statement (and your essay as a whole) is getting at: Social dynamics is really complicated and nuanced, and not getting the difficult parts right results in a lot of problems and overall suffering.

My belief is that just getting the basics right is usually enough to avoid most of the problems. I feel that a lot of the problems the rationality community has with social dynamics is basically due to a failure to simulate other minds (or simply a choice not to). For example, constantly violating small boundaries like being 2 hours late to an appointment. In what world does this behavior count as rational? If you predict yourself not to be able to make an appointment at a given time, why make the appointment at all? If something genuinely unexpected occurs that delays you, but you predict that the other person would be upset with you not informing them, why not tell them? This behavior to me sounds more like deontologically following first-order selfishness, the mistaken belief that rationality is defined as “being first-order selfish all the time.”

When our parents first teach us Basic Morality 101, they often say things like “Put yourself in that person’s shoes”, or “Do unto others” and things like that. And how we usually learn to interpret that is, “imagine yourself as that other person, feeling what they’re feeling and so on, and don’t do things that you imagine would make you unhappy in their situation.” In other words, simulate their experience, and base your actions upon the results of that simulation (TDT?). But then rationalists sometimes claim that socially skilled people are doing a bunch of fast System 1 intuitive calculations that are hyper-complex and difficult to evaluate with System 2 and so on, when it’s not really the case. Simulating another mind, even if you’re just approximating their mind as your mind but with the environmental details changed, isn’t that hard to do (though I imagine some might argue with that), because at the very least most of us can recall a memory of a similar situation. And if you can’t simulate it at all, then you’re probably going to have a tough time being rational in general, because models are what it’s all about. But you don’t need to be a neuroscientist to run these kinds of simulations.

But I haven’t seen that many examples of social dynamics that are 4+ levels deep. I imagine that even showing that such levels exist would be really hard. I think it’s more likely that nerds are not even getting the “obvious” stuff right. I attribute this tendency to nerds’ desire to understand the world symbolically or through abstract theories when doing so would be much harder than just making a model of the situation in your head by predicting things you’ve already observed to happen. And often, nerds won’t do the obvious stuff because they don’t see why it’s strictly necessary within the abstract model they have available. The things nerds typically get flak for in social situations, such as (not an exhaustive list) - shyness, focus on extreme details or highly specific topics, immodesty (in the sense of speaking condescendingly or matter-of-factly), bad hygiene, eccentric hobbies or entertainment—are either things that are irrelevant or non-problematic in the presence of other nerds, or things that can be easily fixed without going 4 levels deep into the intricacies of social dynamics. This is probably an issue of being too much of a Decartesian rationalist when more empiricism is required.

It’s true though, that some of us would like to move higher up in the world which requires less eccentricity or weirdness than is allowable in our closest social circles. In this case, a better understanding of social dynamics would be helpful. But I think that in the case of trying to manage and organize within the rationality community, we’re probably overcomplicating the task a bit.

Thanks. I’m mulling this over, but I think off-the-cuff response is:

a) I agree a lot of nerds mostly need to get the basics right, and bother modeling other minds at all.

b) The thing that this post was a reaction to were naive attempts by rationalists to change culture without understanding what was going on. The most salient example was highlighted in Malcolm’s post (he’s quoting in turn from another post without attribution)

“As Tell Culture was becoming more popular in Berkeley, due to people mostly being excited about the bit in the name, it felt a good deal like I’d had Crocker’s Rules declared upon me at all times without my opt in.”

I think Brienne’s original Tell Culture post contains some warnings about how to do it right, but those warnings weren’t the part that travelled the fastest. I’ve also seen several other rationalist-types attempt to implement game-theoretic-models of how social-circles should be able to operate, while missing important steps. I think this people tended to also have somewhat atypical mental architecture, which makes “just bother to model other people at all” an insufficient solution (i.e putting yourself in someone else’s shoes doesn’t really work if you and they are sufficiently different people).

Basically, the problems that motivated this post were mostly people trying to be cultural pioneers beyond their skill level.

Exactly what I wanted to write. Thank you!

The problem with modelling other people by imagining how I would feel in the same situation is that this method keeps getting the results consistently wrong. I would actually say that my interactions with other people improved when I stopped imagining them as “me, being in a different situation”, and that accepting this was one of the most difficult lessons in my life.

My explicit models are often wrong or don’t give an answer, but they are still better than “putting myself in someone else’s shoes” which was almost guaranteed to return a wrong answer. Other people are not like me; and I kept resisting this piece of information for decades, resulting in a lot of frustration and lost opportunities, probably including the opportunity to develop my social skills a different way, without having them constantly sabotaged by the unconscious desire to imagine other people being “myself, in a different situation”. (Because I would love to find more people who actually are like myself.)

To prevent a motte-and-bailey response, sure, there are many things that me and other people have in common, mostly at or near the physiological level: we love pleasure, hate pain, usually enjoy being smiled at (unless we suspect some ulterior motive), hate being yelled at, etc. Yes, there are thousand similarities.

But there are also many differences, some of which are probably typical for the nerdy or rationalist people, and some may be just my personal quirks. I prefer to know the truth, no matter how good or bad it is. Other people prefer to be told things they already believe, whether correct or incorrect; new information is only acceptable as a form of harmless entertainment. I like to be told where I am wrong, assuming that it comes with a convincing explanation, and is not done as a status move. Other people hate to be told they are wrong, and they are quite likely to punish the messenger. I hate status hierarchies. Most people seem to love them, as long as they are not actively abused. I prefer to cooperate with other people, but many people get competitive—and this is the most difficult part for me to grok—over absurdly unimportant things. (I have already partially updated, and keep expecting that people would stab me in the back if e.g. million dollars would be at stake. But I still keep getting caught by surprise by people who stab me in the back for one dollar; luckily, not literally.) Etc.

So my model of most people is: “cute species, physiologically the same as me, but don’t get confused by the superficial similarities, at some level the analogy stops working.”

Life would be so much easier and my “social skills” much higher if modelling other people as “me, in a different situation” would approximately work. There are a few people with whom this approximately works. With most of the population, it is better (although far from perfect) to model them explicitly as—more or less—someone who wants to be smiled at and hates to be contradicted, and that’s all there is. When I follow this simplistic model, my social skills are okay-ish; I still lack scripts for many specific situations. But imagining other people as “me, in a different situation” is a recipe for frustration.

I believe that other people also have a wrong model of me. (But they probably don’t care, because… what I already wrote above.) At least, when they tell me about their model of me explicitly, I don’t recognize anything familiar. Actually, different people have completely contradictory models of me. Actually, I have a nice, almost experimental-setting experience of this—once I participated at a psychology training, where at one lesson we had to provide a group feedback to each member. A few classmates were missing. The group has just finished giving their group feedback to me, when the missing classmates came and apologized for being late. So the teacher told the other people to shut up, and asked the newcomers only to provide a group feedback to me. What they said was almost exactly the opposite of what the previous group said. -- In other situations different people described as a militant atheist, fanatical catholic, treacherous protestant, brainwashed jehovah witness; a communist, a libertarian, pro-russian, pro-american; a pick-up-artist, a womanizer, an asexual, a gay. My most favorite was a conspiracy theory someone made after reading my blogs (at different place, at different time), concluding that I am not a real person, but instead some weird online psychological project written by multiple people using the same account (apparently that was their Occam razor for how a single blogger could simultaneously care about math, cognitive science, and philanthropy)....

...shortly, if other people completely fail to simulate me, using the symetrical algorithm of imagining themselves at my place, why should I expect to achieve better results by using the same algorithm on them? Just because it mostly works when one average person simulated another? (And I am saying “mostly” here, because as far as I know, the interactions of average people with each other are still full of misunderstandings.)

I find what you said about the competitiveness aspect of other people the most compelling, but aside from that, I’ve had increasing success with imagining someone else as myself but in another situation. It takes breaking down what a “situation” is and entails, and how entrenched it is into our identity. Think of times in your life when you were vastly different. Maybe you were stressed about your first SO in high school—perhaps someone you can’t even imagine liking now. Can you successfully pretend, through the haze of time, being as obsessed over that person now as you were then? Is anything blocking that sensation, and if so, what?

Back when I was a sophomore in undergrad, I had a “bro”-like roommate. I was your typical college hipster, and he had a very abrasive approach to camaraderie. (He was not unlike the competitive type you describe.) I had the hardest damn time trying to figure out what was going on in his head, and one day he called me out for my introverted personality, misreading my reclusiveness as conceit. When he did that, I remember crying in my room, because there was this fundamental misunderstanding between us. He didn’t understand my approach or emotionality, and I didn’t get his. But over time I had a sensationally gradual realization that I could actually interact with this guy as “one of his own.” It started as mimicry, and I did “toughen up” a little through this event, but it also gave me an idea.

Before this time, I didn’t codify what it actually meant to feel like someone else. You can’t walk a mile in someone else’s shoes if they don’t fit your feet, right? When I was able to (in part) embody his approach to the world (while retaining my own on a backburner), it was easier to realize that this kind of sensational transition is necessary for everyone. It isn’t that we are fundamentally different, always, full-stop. It’s just that we can’t just start imagining someone else’s experiences a priori without forgetting who we are for a little while.

Don’t mistake this for spiritual chakra mumbo-jumbo or what-have-you, all I mean is that there is a mundane, demonstrable relationship between the body and all of the factors influencing it. You might be able to consider some of these factors a priori, but take care to recognize that your evaluation of their count and intensity may not at all be accurate, and that estimate could very well be blurred by an opposing sensation (or lack thereof) that your self currently retains.

But when you do become someone else, or rather, when your identity is changing shape to accommodate some grief or other perhaps more complicated sensation, take note of the nature of that change. Even if you can’t fully comprehend someone else’s motivations as your own, taking note of how you change shape and generalizing that this can happen to wildly varying degrees within our species (thinking about a civilian’s mental adjustment to being a soldier, accruing PTSD, etc), can be a very helpful placeholder for imagining the experiences of someone else’s life, and recognizing their actions as reasonable, given the possible constraints.

Can confirm :-)

I agree that in general people can differ pretty substantially in terms of preferences and interactions in a way that makes golden rule style simulations ineffective.

e.g. I seem to prefer different topics of small talk than some people I know, so if they ask me to, say, go into details about random excerpts of my day at work I get a bit annoyed whereas if I ask them mirror questions they feel comfortable and cared for. So both of us put the other off by doing a golden rule simulation, and we’ve had to come up with an actual model of the individual to in order to effectively care for the other person.

At the same time, some of these examples you give to me feel like inside view vs outside view explanations, in particular this line stood out:

I think a fairly common failing is for people not to consider closely how the other will feel when some information is related to them (I know I personally am often less considerate in my words than is warranted). I think it’s not so uncommon to feel attacked by someone who was merely inconsiderate rather than attacking, partially because it really is hard to be sure of which the other person is until it’s too late (being considerate towards an ambiguous person who was attacking often opens up a substantially larger attack surface).

The failure of “put yourself in their shoes” seems similar to the failure of “do to others as you’d have them do to you”. You have to be hyperaware of each way that the person you’re modeling is different from you, and be willing to use these details as tools that can be applied to other things you know about them. This is where I actually find the ideas of guess/ask/tell culture to be the most helpful. They honestly seem pretty useless when not combined with modeling, precisely because it turns into “this is the one I have picked and you just have to deal with it”.

Even something simple as “hate pain” isn’t as straightforward. There are plenty of masochists out there who choose to act in a way that painful to them. Pain can make people feel alive.

I might be closer to normal people in terms of mental models compared to other people here on LW. Or the people I’m around at school may also be more interesting than average. (Or many other possibilities...)

But the point seems to be that I find that neither of these models tend to match my interpersonal experiences.

To be clear, I think there exists models of abstraction where it might be more convenient to treat people as NPC’s and/or driven by simplified incentives.

For the most part, though, my face-to-face interactions with people has me modeling them as “people with preferences that might be very different from mine, perhaps missing some explicit levels of metacognition, but overall still thinking about the world”.

This doesn’t preclude my ability to have good discussions, I don’t think.

In conversations, I’ll try to focus on shared areas of interest, cultivate a curiosity towards their preferences, or use the whole interaction as an exercise to try and see how far I can bridge the inferential gap towards things I’m interested in. And this ends up working fairly well in practice.

(EX: rationality-type material about motivation seems to be generally of interest to people, and going at it from either the psychology or procrastination angle is a good way to get people hooked.)

Yeah, this is pretty much what I do, too. (Well, when I remember to do this.) But “how far I can bridge the inferential gap towards things I’m interested in” usually doesn’t get far before things get rounded to nearest cliche.

The problem is to keep remembering that I cannot say anything “weird”. Which includes almost everything I am interested at. Which includes even the way I look at things other people happen to be also interested about.

As an approximation, when I successfully suppress most of what makes me me, and channel my inner ELIZA, sometimes I even receive feedback on having good social skills. Doing this doesn’t feel emotionally satisfying to me, though.

I’ve found that people who are “on the clock” so to speak (that is, are at that moment talking with you solely because of a job they’re doing) are almost always easier to interact with when treated as NPCs with a limited script that is traversed mostly like a flowchart.

Police officers pulling you over, wait staff at a restaurant, and phone technical support representatives (to name some examples) are sometimes literally following a script. It can be helpful for both of you to know their script and to follow it yourself.

Heavy +1 to going in the direction of becoming simpler and more transparently a good trustworthy person.

Separately, all discussion of X culture makes me want to scream.

‘try being naively good first’ has been a surprisingly useful thought.

I’m somewhat surprised at the notion of “just be trustworthy” being helpful for anyone, though maybe that’s because of an assumption that anyone who doesn’t already employ this tactic must have considered it and have solid reasons to not use it?

I think by default, the main way rationalists become less trustworthy is not on purpose: it comes from a form of naive consequentialism where you do things like make plans with people and then abandon them for better plans without considering the larger effect of this sort of behavior on how much people trust you. One way to say it is that one of the main consequences of you taking an action is to update other people’s models of you and this is a consequence that naive consequentialists typically undervalue.

That seems like a possible selection effect.

In my case, I find Romeo’s approximation to be a fairly good descriptor of how I operate. There’s obviously a whole bunch of conditionals, of course, and if I were to try and reduce it down, it might look like:

In general: 1) Talking to someone? Figure out what they’re interested in, and how you can offer resources to help them advance their goals. 2) If there’s tangential overlap, maybe mention your own goals. 3) Iterate back and forth for a while with questions.

If you’re generally interested in learning more about the other person, they tend to reciprocate in nice ways, e.g. giving attention to your own stuff. [I think this is enough of an approximation to “just be naively good”?]

Then there’s a few corollaries: a) With a casual friend? Intersperse conversation with banter. b) Talking to someone new? Use generally accepted stereotype phrases (comment on weather, etc.) and then introduce yourself. Maybe start by complimenting something of theirs.

But all of this is fairly black-boxed, and I tend not to operate by explicitly reasoning these things out, i.e. the above rules are a result of my applying introspection / reductionism to what are usually “hidden” rules.

The closest I get to any of the (weird-from-my-perspective) recursive modeling / explicit reasoning is when I have no idea what to say. In such a case, I might ask myself, “What would [insert socially adept friend] do?” which queries my inner simulator of them and often spits out passable suggestions.

I don’t like the framework of using guess, ask and tell culture as the main tools for choosing how to communicate. Not even as a first aid.

The framework of nonviolent communication provides concrete tools. If you are interested in learning nonviolent communication you can go to a workshop and be in an environment where there’s deliberate practice of the core skills of nonviolent communication. If you live in an extremely violent neighborhood where you might be killed for appearing weak, nonviolent communication might lead to bad outcomes. Heavily political environments where other people only care about scoring points against yourself can also be problematic.However, in most social contexts skillful nonviolent communication provides better outcomes than the behavior of a nerd before learning the skills.

Nonviolent communication is a series of rhetorical moves. You can call someone who engages in the moves of nonviolent communication for most of his social interaction a “reveal culture” or “ask culture” person but that isn’t a full description. A rationalist who comes into the culture observes that people are pretty open might make errors when he communicates outside of the way nonviolent communication works.

All this talk about cultures doesn’t change whether social interaction feels draining or feels like it is giving you energy. If you however, do nonviolent communication decently that experience usually won’t feel draining. The debate about the culture doesn’t change the underlying emotions. A person who fears conflict will have a hard time with an enviroment in which a lot is revealed even when they decide that they want to like reveal or ask culture. Many rationalists aren’t comfortable with social conflict, so the interaction is still draining instead of giving energy.

Is my point to recommend nonviolent communication? No. I’m not even fully trained in nonviolent communication myself. I just use nonviolent communication as an example because it’s well known, even when it’s sometimes cargo-culted by people who don’t understand the core.There are many existing paradigms of communication that are the result of years or decades of work by skillful individuals.

As a community we should put more effort into integrating work that other people already did. The PUA community is unfortunately very visible for nerds who get their information about how to train social skills from the internet but there are many other communities that exists that have their ways of training social skills.

I think Circling (Authentic Relating), Radical Honesty and the Wheel of Consent are all paradigms where our community would benefit from integrating parts of it. Unfortunately all of the three aren’t easily learned by reading a few blog posts. They have exercises. They can be learned through deliberate practice and that’s valuable.

I didn’t respond to this at the time because I was crunching for the Unconference, but wanted to follow up and say:

I think all the frameworks you mention are good frameworks (FYI, there was a Circling workshop at the Unconference). There is a sense in which I think they are better designed than Ask or Guess culture, mostly by virtue of having been designed on purpose at all instead of randomly cobbled together by social evolution, as well as by virtue of “it’s clear that you’re supposed to actually practice them instead of just adopting them blindly.”

But also think your take on NVC here is making a similar reference class of mistake to the people who are dismissing any particular Ask/Guess/Interrupt/whatever culture. The system works for you, but it’s not going to work for everyone. (I know some people that find NVC and Circling infuriating. A counterpoint is that their descriptions of NVC/Circling involve people ‘doing it wrong’ (i.e. end up using it passive aggressively, or manipulatively). But THEIR counterpoint to that is that you can’t trust people to actually know what they’re doing with these techniques, or not to misuse them)

One of the main thesis of this post was supposed to be “all these other ways of being that seem stupid or crazy to you have actual reasons that people like them, that you can’t just round off as ‘some people like dumb things’. If you want to be socially successful, you need to understand what’s going on and why a person would actually want [or not want] these things.”

My argument has nothing to do with NVC working for me. NVC is not a system in which I’m well trained nor that I advocate this community to do more NVC. I explicitly said so in my post, but you still make that objection because it’s an easy objection to make you can make without addressing the substance of my argument.

Often descriptions are not simply ‘doing it wrong’ in the sense of using it ‘passive aggressively or manipulatively’ but rather providing example where they think the example describes NVC but which violates core NVC concepts.

I remember a tumbler post providing an example where a person said “I feel violated” in a passive-aggressive way. They thought that the example illustrates a person expressing their feelings. In NVC “I feel violated” is not an expression of a real feeling. It’s not complicated to see that it isn’t for a person who went far enough into NVC to have read and understand the book but a single blog post like the WikiHow post.

I agree in the sense that you can’t trust a person who read a blog post about NVC to know what they are doing when they try to do NVC. The same goes for many people who read the book and various seminars on Youtube. You generally need in-person training to transfer these kinds of skills in a way where you can trust that the learner knows what they are doing. Teacher quality does matter, but if you have a decent teacher the students also can learn what they are doing.

Reading the WikiHow post and trying to follow it’s scripts can work but it can also end up in cargo-culting NVC.

Yes, there are many ideas that have actual reasons why people like them. Astrology is liked by many people. I can have a debate about why people like astrology but it’s a very different debate from the debate about whether more rationalists should adopt astrology.

That seems to me like a fairly trivial intuitive idea. I would guess that the idea seems intuitively true to many rationalists. At the same time I don’t think you have provided a decent argument for it being true. You spent no effort into investigating the counter-thesis or provided any empiric evidence for the claim.

To use your Harry Potter framing, the idea that understanding is necessary to be successful is a Ravenclaw idea. I do believe that understanding is helpful or I wouldn’t be on LessWrong but I think there are plenty of people who are socially successful who don’t understand very much. Their charisma along with engaging in high status behavior can sometimes be enough.

I retract my “to be socially successful, you must X” point—it’s obviously false, plenty of people are socially successful without understanding much of anything.

I think there was a different point I was trying to make, which was more like: “I see people actively dismissing some of these conversational styles and the accompanying skills required for them, and I see that having explicit impacts on how the rationality community is perceived, (which ends up painting all of us with a “overconfident, unfriendly and bad at social grace” brush) which is making it harder for our good ideas to be accepted.”

So I think my argument is something like a) I think this specific cluster of people (who are Ravenclaws) are dismissing something because they don’t understand it and this is having bad effects, and b) in addition to the bad effects, it’s just irritating to me to see people preoccupied with truth to dismiss something that they don’t understand. (this latter point should NOT be universally compelling but may happen to be compelling to the people I’m complaining about)

The specific point I was responding to was “All this talk about cultures doesn’t change whether social interaction feels draining or feels like it is giving you energy. If you however, do nonviolent communication decently that experience usually won’t feel draining.” This seemed explicitly born out of your experience and doesn’t seem obviously true to me (it hasn’t been my experience—I’ve gotten good things out of NVC but ‘communication that wasn’t draining’ wasn’t one of them).

I’m… actually not sure I understand what your argument actually was. I read it as saying “metaframework X isn’t a good framework for discussing how to communicate. Metaramework Y is better.” (With metaframework Y loosely pointing at the cluster of things shared by Circling, NVC and others).

I think you provided evidence those frameworks are useful. (I agree, I’ve personally used two of them, and do think the cluster they are a part of is an important piece of the overall puzzle). I don’t think those frameworks accomplish the same set of things as the things I was mostly talking about it in this post, and if that was an important piece of your point I don’t think you provided much evidence for it.

That hypothesis is backed by personal experience in the sense that when I’m anxious about a social action and suppressed that emotion that’s a draining social interaction.

It’s also supported by a bunch more theoretic arguments.

Then there’s the hypothesis that well done NVC resolves the emotion. That’s again a hypothesis build on some experience and a bunch of theory about emotions.

To assess whether you practice NVC I might look at a post where you wrote your motivation for this series of blog posts ( http://lesswrong.com/lw/ouc/project_hufflepuff_planting_the_flag/ ) . A person from whom NVC is deeply integrated is likely going to make NVC rhetorical moves.

You do reveal your needs by saying “I like being clever. I like pursuing ambitious goals.” That’s nice but I imagine that it’s mean to say that you run project Hufflepuff simply because you like being clever and you like to pursue ambitious projects. I imagine that you do feel a desire to have a community that’s nicer to each other and that feels more connected to each other, however you don’t explicitly express that desire in your post.

This suggests to me that the NVC rhetorical moves aren’t deeply ingrained in your communication habits. Given that they aren’t deeply ingrained I would expect that it frequently happens in communications that you feel something and don’t express the feeling or the needs and afterwards feel drained.

If you actually spent a decent amount of time in NVC workshops, that would be interesting to know and might cause me to update in the direction of NVC being a framework that’s harder to use in practice.

The point was frameworks that are based on empiric experience, where there are exercises that have been refined for years are better than a framework like ask/guess culture that’s basically about an observation that’s turned into a blog post. Even when the blog post has been written by an respected community member and the framework with years of refining through practice is created by an outsider, the framework with longer history is still preferable.

My personal hypothesis on the subject is that social interaction often feels draining for people because they inhibit their emotions. If Bob worries about what Alice thinks of him and doesn’t express the emotion there’s a good chance that he will feel drained after the interaction.

That hypothesis is backed by personal experience in the sense that when I’m anxious about a social action and suppressed that emotion that’s a draining social interaction. It’s also supported by a bunch more theoretic arguments.

If I

My argument

The point was metaframeworks that are based on empiric experience, where there are exercises that have been refined for years are better than a framework like ask/guess culture that’s basically about an observation that’s turned into a blog post.

I’ve had a strong urge to ask about the relation between Project Hufflepuff and group epistemic rationality since you started writing this sequence. This also seems like a good time to ask because your criticism of the essays that you cite (with the caveat that you believe them to contain grains of truth) seems fundamentally to be an epistemological one. Your final remarks are altogether an uncontroversial epistemological prescription, “We have time and we should use it because other things equal taking more time increases the reliability of our reasoning.”

So, if I take it that your criticism of the lack of understanding in this area is an epistemological one, then I can imagine this sequence going one of two ways. The one way is that you’ll solve the problem, or some of it, with your individual epistemological abilities, or at least start on this and have others assist. The other way is that before discussing culture directly, you’ll discuss group epistemic rationality, bootstrapping the community’s ability to reason reliably about itself. But I don’t really like to press people on what’s coming later in their sequence. That’s what the sequence is for. Maybe I can ask some pointed questions instead.

Do you think group epistemic rationality is prior to the sort of group instrumental rationality that you’re focusing on right now? I’m not trying to stay hyperfocused on epistemic rationality per se. I’m saying that you’ve demonstrated that the group has not historically done well in an epistemological sense on understanding the open problems in this area of group instrumental rationality that you’re focusing on right now, and now I’m wondering if you, or anyone else, think that’s just a failure thus far that can be corrected by individual epistemological means only and distributed to the group, or if you think that it’s a systemic failure of the group to arrive at accurate collective judgments. Of course it’s hardly a sharp dichotomy. If one thought the latter, then one might conclude that it is important to recurse to social epistemology for entirely instrumental reasons.

If group epistemic rationality is not prior to the sort of instrumental rationality that you’re focusing on right now, then do you think it would be nevertheless more effective to address that problem first? Have you considered that in the past? Of course, it’s not entirely necessary that these topics be discussed consecutively, as opposed to simultaneously.

How common do you think knowledge of academic literature relevant to group epistemic rationality is in this group? Like, as a proxy, what proportion of people do you think know about shared information bias? The only sort of thing like this I’ve seen as common knowledge in this group is informational cascades. Just taking an opportunity to try and figure out how much private information I have, because if I have a lot, then that’s bad.

How does Project Hufflepuff relate to other group projects like LW 2.0/the New Rationality Organization, and all of the various calls for improving the quality of our social-epistemological activities? I now notice that all of those seem quite closely focused on discussion media.

I think there’s a consistent epistemic failure that leads to throwing away millennia of instrumental optimization of group dynamics in favor of a clever idea that someone had last Thursday. The narrative of extreme individual improvement borders on insanity: you think you can land on a global optimum with 30 years of one-shot optimization?

Academia may have a better process, and individual intelligence may be more targeted, but natural + memetic selection has had a LOOOT more time and data to work with. We’ll be much stronger for learning how to leverage already-existing processes than in learning how to reinvent the wheel really quickly.

Do you think I disagree with that?

I think this comment is the citation you’re looking for.

Thanks!