The Fall of Rome, III: Progress Did Not Exist

The Malthusian Trap is a famous idea in regards to population pressure. Agricultural progress is linear, population growth is exponential. Inevitably, the population size exceeds the carrying capacity of its farmland. This results in starvation, disease and (civil) war, which reduces the population size. Afterwards, the population can grow again and the cycle repeats.

It’s a relatively horrible perspective, and it makes agricultural developments very valuable. Innovate quickly enough, and you can prevent death and war.

Malthus came up with this idea in the 18th century. It led to well-intentioned attempts to spread ‘modern’ agricultural methods around the world—which did not work, much to the chagrin of many Europeans.

In the 20th century, the Danish economist Ester Boserup came along. She investigated methods of agricultural intensification and concluded that historically, they were terrible. We modern people are used to technological advances being awesome. Modern cars are safer, more efficient and more comfortable than cars from 50 years ago. Modern PCs are cheaper, smaller and more powerful than PCs from 20 years ago. Technology improves our lives.

But that’s not true for pre-industrial agricultural tech. The most primitive agricultural method is slash-and-burn agriculture. Take a random piece of forest and burn it. The ashes will make the ground highly fertile. Throw some seeds in there, wait a summer, and crops will grow without much effort. You might be able to use the same plot of land for a couple of years, but then you’ll have exhausted the soil. On to the next piece of forest!

The first farmers in an uninhabited area will be able to utilize this method. It’ll take roughly thirty years for the forest to regrow, allowing farmers to repeat the cycle. But it does mean that each farmer will need a lot of land.

As the population grows, the land available to each farmer decreases. More crops need to be produced per square meter. Agricultural intensification becomes necessary. Human labor will need to replenish the soil and to optimize yields. The soil will have to be ploughed, manure needs to be spread, weeds need to be removed, perhaps the soil will have to be drained of excess water, or irrigation systems need to be built and maintained.

This is a lot of work. And humans are lazy efficient. So agricultural intensification only happens when population pressure forces farmers to do so. It’s not like ploughs were invented and everybody cheered and adopted the idea because ploughing is so much fun. Only when land is scarce and yields need to be improved, humans start to plough. Teach people in low-density areas how to plough and they’ll discard your ‘innovation’ as soon as possible.

From a civilizational perspective, agricultural intensification is great. It allows for higher population densities and the growth of larger cities, and networks of cities. This leads to the specialization of labor and to more advanced technologies. But does it really benefit the individual? If I had to live in 3000BC, I think I’d rather be a farmer in sparsely populated Europe than in a crowded village along the Egyptian Nile.

History Moves North?

I’m Dutch, but our history books in school always start in Egypt. Ancient Egypt, where civilization, writing and religion were invented. Then, in the next chapter, as the timeline progresses, we suddenly jump to Ancient Greece. Then we move towards Ancient Rome, followed by Charlemagne in France around 800AD. Only at the end of the Medieval Period do we really start focussing on the Netherlands and Northern Europe.

That’s strange, right? Why does our focus shift so much geographically? Why does it seem to trend towards the north? The books that follow this pattern don’t explain why. I wondered about it for a while, but Boserup’s theory on the development of agriculture seems to explain a lot of it.

Imagine two water taps filling two different buckets at the same pace. One bucket is narrow, the other is wide.

The narrow bucket will be filled to a higher level quicker than the wide one. Ultimately, the wide one will contain more water. Let’s take a look at modern day Egypt from a satellite’s perspective.

There’s the Nile in the middle, surrounded by a stretch of fertile land, bordered by desert. Imagine being born there in 3000BC. It’s crowded and land is scarce. To produce food, you need to work your tiny plot of land very intensively. You could move north or south, but the situation is identical there. You could move to the west or the east, but that’s an infertile desert. The logical choice is to work the land intensively.

But compare that to Europe in the same era! The land is fertile and sparsely inhabited in all directions. If a certain area is accidentally densely populated, people are free to move away and lead more relaxed lives with less intense agriculture. Which sounds nice for those individuals, but it does lead to a complete lack of dense cities and related innovations in Europe in that time period.

But the metaphorical Water Tap of Population Growth keeps running and buckets keep filling up. Where does the first European civilization emerge? Not in the wide plains and forests of Germany. It’s on the small Greek islands and in the Greek valleys, separated by uninhabitable seas and mountains, where the light of European civilization is kindled.

It’s a lot of narrow buckets next to each other. Of course they’re the first European buckets where the water reaches a high level!

Explaining the rest of the trend seems relatively obvious. Before Central and Northern Europe “fill up” with intensively worked farmland and a network of cities, it’s the Italian peninsula where this process unfolds. When Roman armies conquer northern Europe in the first century BC, they fight rather primitive natives who haven’t entered the Iron Age and who cannot write. After the Romans are defeated, the natives build the Palatine Chapel in Aachen around 800AD.

In the same period, European agricultural technology rapidly developed. I’ll directly quote Wikipedia:

The Romans achieved a heavy-wheeled mould-board plough in the late 3rd and 4th century AD, for which archaeological evidence appears, for instance, in Roman Britain. The first indisputable appearance after the Roman period is in a northern Italian document of 643. Old words connected with the heavy plough and its use appear in Slavic, suggesting possible early use in that region. General adoption of the carruca heavy plough in Europe seems to have accompanied adoption of the three-field system in the later 8th and early 9th centuries, leading to improved agricultural productivity per unit of land in northern Europe

Remember what we’ve learned: humans don’t adopt more labor-intensive agricultural methods until population pressure forces them to do so. What do late-Roman and Early Medieval Europeans seem to do? Adopt more labor-intensive agricultural methods. Conclusion: the population must have grown. What’s the only way to explain firewood/charcoal/forests becoming rarer and more expensive in the late-Roman / Early Medieval Period? A growing population putting more pressure on land.

Modern humans see ‘Progress’ as a rising tide lifting all boats in all aspects. The population grows, people become wealthier and healthier, they have more spare time, they become more civilized, more educated, more peaceful. It’s all connected. So when material wealth diminishes, populations must shrink as well, right?

I don’t think we can assume that about the late-Roman and Early Medieval Period. People in brick houses with roof tiles drinking wine from amphorae and eating food from decent earthenware leave a lot of traces.

People in wooden houses with straw roofs drinking beer from wooden barrels and eating food from wooden plates don’t. That doesn’t mean they did not exist. They could even have been more numerous than their wealthier ancestors. It would certainly explain why fuel became more expensive, and why fuel-intensive practices fell out of use.

So that’s my basic theory. Somewhere in the last centuries BCE, the Romans became very successful. They had a network of cities that were properly organized, they built infrastructure, they improved the production of iron and charcoal, and they exploited their environment and less densely inhabited areas effectively.

Their success led to a serious population boom in a large part of Europe. Fertile land per human decreased necessarily. As the population kept growing, fuel became more expensive. Why grow trees for bathhouse fuel, when you can grow crops for your children? In some ways, this is sensible and an improvement above the old situation of a more sparsely populated Europe. In other ways, this is a serious decrease in living standards and a deterioration of civilization. It’s not Universal Progress In All Aspects; it’s an increase in population density with benefits and drawbacks.

There’s a lot more to say about related subjects, but this explains the core of a new perspective on the Fall of Rome. Thanks for reading all of this, and I’d love to hear your opinion.

Previous: The Fall of Rome, II: Energy Problems?

There’s another explanation for why the history books display that progression you mapped out: They are Dutch history books, so naturally they want to focus on the bits of history that are especially relevant to the Dutch. One should expect that the “center of action” of these books drifts towards the Netherlands over time, just as it drifts towards the USA over time in the USA, and (I would predict) towards Indonesia over time in Indonesia, towards Japan over time in Japan, etc.

Sure! I don’t think the fact that Dutch history books end in the Netherlands is good evidence that the Netherlands is the most significant place in world history :)

But Ancient Egypt, Classical Greece and Classical Rome do seem to be of global significance. Greek ideas and inventions, from Aristotle to the Antikythera mechanism, do seem to be lasting and unique. And a bit harsher: the Greeks conquered Egypt. The Romans conquered Greece and Egypt. The balance of power actually seems to have shifted in that direction.

This sequence was incredibly interesting while also being very short and to the point. Thanks a great deal for writing it.

Generally speaking i think your hypothesis is interesting and plausible.

A few questions

For the narrow vs wide glass metaphor for population, does it really line up with the multi-century timelines involved? If populations can grow 2x every 20 years in these societies, wouldn’t europe have filled up with people much faster? Isn’t the fact that it didn’t down to a lack of technology (complex agriculture and settled states able to defend agriculture)?

How much evidence is there that concrete production fell due to lack of fuel as opposed to, say, economic collapse and constant civil wars drastically reducing demand for very expensive high-grade building materials?

Your model of intensive agriculture seems to be “everyone knows what it is but people won’t do it until it’s necessary”. Is this true? Isn’t intensive agri a super advanced tech which took centuries to develop and diffuse? Isn’t every pre-industrial society pretty much permanently at the malthusian limit, meaning everyone would already have an incentive to do intensive agriculture if possible.

Do you think the greeks developed so quickly because they were land bound and hence had to resort to intensive agriculture? Why not other hypothesis like them being next to the sea = hugely more mobility + trade = hugely more wealth = higher pop densities and more specialization in complex good creation.

Thanks a lot!

In regards to your last point: I’ll certainly concede that naval mobility must have been very helpful to the Greeks. As a Dutch person, I’m well aware how helpful sea-based trade was, historically :)

In regards to the third point: are you aware that early farmers were shorter and had significantly worse health than hunter-gatherers? I don’t believe it was an amazing new invention, it’s a thing desperate, hungry people do when ‘wild’ food resources run out. It allowed for sedentary life and higher population densities, and in the very long term that’s crucial for ‘civilization’, but it was not an improvement for the individual.

I believe that trade-off didn’t happen merely at the start, when the first hunter-gatherers switched to agriculture, I believe that trade-off to have increased gradually as agriculture became more intensive.

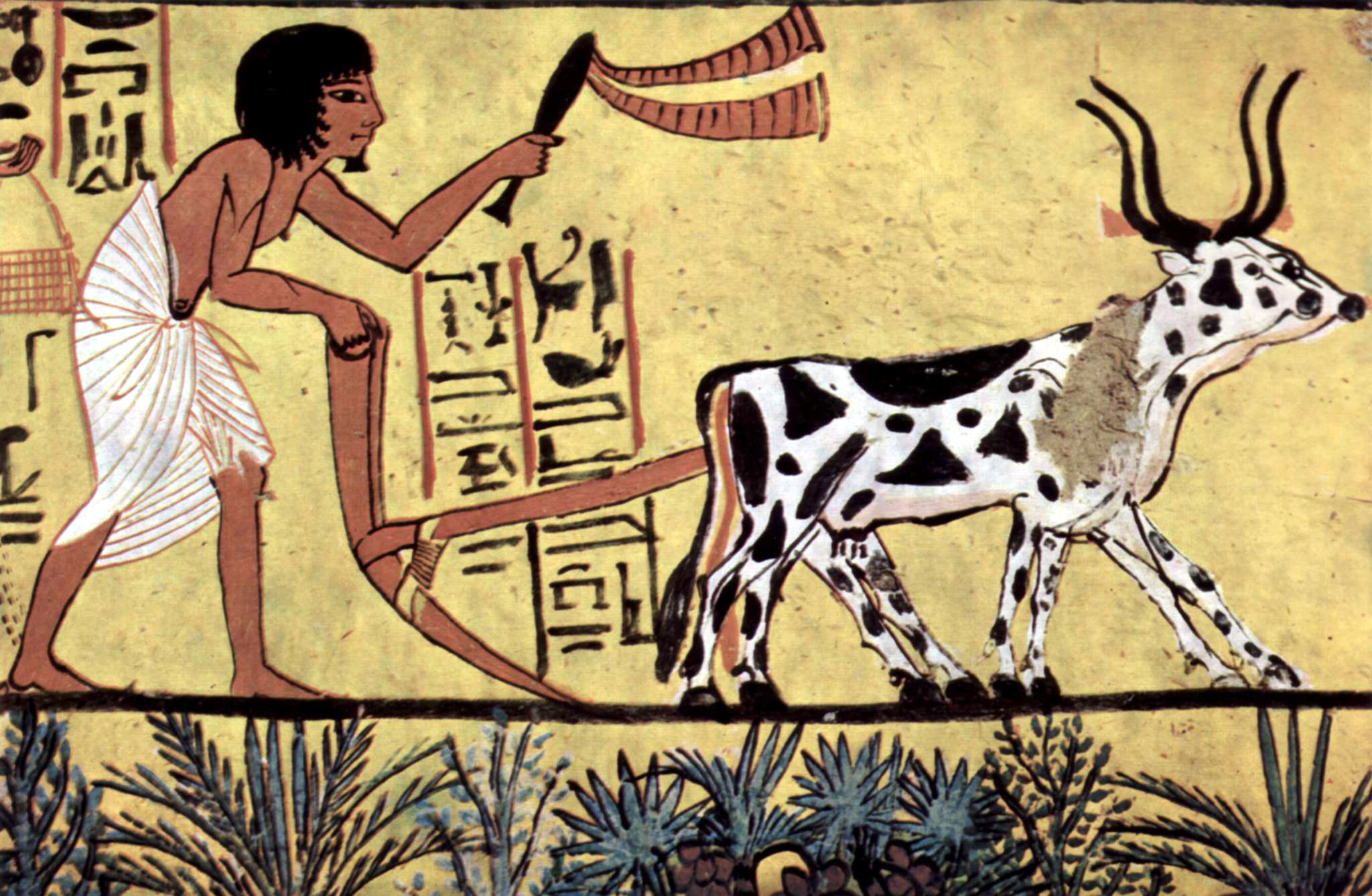

I’m going to be deeply unfair here and it’s easy to criticize these emotional arguments, but look at this drawing of a Bronze Age farm versus Victorian London homes, at the start of the Industrial Revolution. Victorian England had way more advanced technology, and as an empire, it had very impressive stats. But I doubt I wanted to live there as a middle-class or poor individual. (Not saying the Bronze Age was awesome, but day-to-day life may have been more tolerable).

I think Ancient Egypt must have been similarly terrible for individuals. Long hours of hard physical farm labor in dense, crowded villages. It creates mighty nations, but I doubt it was good for individual well-being. Consider Zvi’s writings on slack.

Make sure that under normal conditions you have Slack. Value it. Guard it. Spend it only when Worth It. If you lose it, fight to get it back. This provides motivation for fighting things Out To Get You, lest you let them eat your Slack.

I believe our ancestors were human beings just like you and I. They valued slack as well. And they guarded it as well. There is a lot you can do to optimize crop yield. They weren’t desperate for technology and knowledge, they were desperate for time and energy. They didn’t plough and do all the other requirements of the most intensive agriculture unless absolutely forced to by necessity—by population pressure and land scarcity.

Think of COVID. (Disclaimer: The Netherlands has sky-high infections, overwhelmed ICs and a relatively low amount of vaccinations) We act like we’re doing ‘our best’, like we really care, and like we really want to end this pandemic. But we don’t. 99% of infected people survive, only the elderly have a serious chance of dying, so a lot of people act like it’s pretty much a flu and are not going to put their lives on hold for that.

I’m 100% certain that if a way more deadly disease entered the Netherlands, we suddenly were able to take more drastic measures and actually stop that virus in its tracks. Which means we currently are not doing our best at fighting the pandemic according to our full pandemic-fighting potential, we are doing our best according to “we consider this to be a very serious flu”-potential.

I don’t think our ancestors were 24⁄7 operating on their actual this is our crop yield if we put all our effort in it potential. They were guarding their slack and trying to enjoy their lives, and they were not using all potential agricultural technology and knowledge. Ester Boserup has countless examples of this. German colonists in Argentina quickly dropped their intensive agriculture because they weren’t so land-constrained there. Sparsely populated Indonesian islands had extensive contact with other densely populated islands without adopting their agricultural technology, only doing so when their own population grew.

In regards to your first point: consider the text above. I don’t believe humans tried to optimize for population density, because it decreased their quality of life. I agree that Europe could have been become a lot denser, a lot quicker if people were rationally aiming for that, but they weren’t.

Sure, if it was just concrete that disappeared, I could believe that. But simultaneously, nearly all fuel-intensive luxuries disappear. And a lot of them, including concrete, suddenly reappear when new cheap fuel sources become available. That makes it really plausible to me that fuel is indeed the crucial element.

So I think that the explanations for the gradual spread of ever more intense agriculture are:

The population growth explanation: people gradually adopted more intense agriculture because population density rose, meaning they had to or they would starve.

The technological diffusion model: intensive agriculture was highly complex and non-obvious. The tech for it was developed in a few places and then gradually diffused. The causal link between pop and intensive agriculture is that intensive agriculture caused higher, more concentrated populations rather than being caused by it.

Why do I tend towards the latter hypothesis? A few reasons:

In pre-modern civilizations, population growth is exponential or at least very rapid. This means that if it indeed was pop density growth driving agriculture, we would expect to see far rapider adoption of it in, say, non costal europe where it took close to a thousand years after the greeks had it.

Related to the above, most pre modern societies were at the malthusian limit due to unrestrained population growth. Famines were common and starvation was a real risk most people would face multiple times in their lives. Hence I don’t think people in these societies lacked an incentive to grow more food more efficiently, even if doing so was hard. I think they just couldn’t.

The narrow/wide bucket analogy is neat; it is a good thinking tool. That said, I am by no means a historian, and do not know how good of a model it actually is. Some scattered thoughts:

The metaphorical bucket overflowing means unavoidable innovation, not system collapse per se. It seems to me like the narrow bucket can overflow many times, and each time it does it gets wider. That completely changes the model: no longer does it explain this ‘shift towards the north’.

As for Rome, it had long exhausted the surrounding lands before it collapsed. Its bucket overflowed many many times. One of the innovations they made is to cultivate grain in distant lands and ship it to Rome in huge quantities (Im sure they weren’t the first to do this but the scale is massive). Your bucket-theory is tightly coupled to people exploiting their surroundings only, and this breaks the model completely in my opinion.

A good source for reading in this vein is this blog, in case you haven’t seen it yet. This specific article is about land exploitation from a city point-of-view, but I think it’s very much related.

Thanks!

In regards to the bucket metaphor: the ‘width’ is the amount of fertile land available to its inhabitants.

Water only starts ‘stacking’, going ‘up’, if it can’t go ‘down’ or ‘to the sides’ anymore. The walls of a bucket prevent sidewards expansion and force the water level to go up.

Like water, pre-industrial humans had good reasons to avoid ‘stacking’ as well. Population density forces farmers (which is 90%+ of the population in pre-industrial times) to adopt more labor-intensive practices. So when humans had the chance, they preferred to spread out.

When hunter-gatherers cannot find enough food anymore, and all surrounding lands are exhausted by other hunter-gatherers, ‘spreading out’ ceases to be a viable method. ‘HumanWater’ has spread as far as it can, and now it will start to ‘stack’: hunter-gatherers will adopt slash-and-burn agriculture, raising the potential population density. When slash-and-burn agriculture has spread through the entire ‘bucket’ (all reachable fertile ground), the next agricultural step is implemented. The easiest one: they don’t go from slash-and-burn agriculture to plowing, irrigating, weeding and spreading manure in one generation. It happens step by step, starting with the least labor intensive ‘upgrade’ and only escalating when forced to.

I hadn’t really considering overflowing buckets, but for example, the Greek colonisation might be a good example of that happening:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Greek_colonisation

I love the blog you linked! Funny to see the screengrabs from Game of Thrones, that exact problem bothered me as well :)

The term “unavoidable innovation” really irks me. It has become this teacher’s password for all the world’s uncomfortable questions. Why was Malthus wrong? Innovation! How do we prevent civilizational collapse? Innovation! How do we solve competition and conflicts for limited resources? Innovation! How can we raise the standard of living without compromising the environment? Innovation!

As if life was fair and nature’s challenges were all calibrated to our abilities such that every time we run into population limits, the innovation fairy appears and offers us a way out of the crisis. Where real disaster can only ever result from corruption, greed, power struggles and, y’know, things that generally fit our moral aesthetics about how things ought to go wrong; things that would make a good House of Cards episode.

Certainly not mundane causes like mere exponential population increase. Because that would imply that Malthus was (at least sometimes) right, that life was a ruthless war of all against all, a rapacious hardscrapple frontier. An implication too horrible to ever be true.

I’m not arguing that the Malthusian trap explains all the civilizational collapses in history, or even Rome in particular. But it is the default failure mode because exponential growth is fast and unbounded, so to avoid it your civilization has to A) prevent population growth altogether, B) outpace population growth with innovation consistently, or C) collapse from another cause way before population pressure becomes a problem.

I am not sure what you are arguing here. First of all, I will completely agree with you that ‘innovation’ is not an explanation, and so we should be wary of it being used as such. I don’t actually think the bucket analogy has much explanatory power (though I find the concept interesting and worthy of further exploration). Using the term ‘unavoidable innovation’ was my attempt to clarify the analogy in order to be able to point out where in my opinion it fails.

The model in fact attempts to explain why innovation happens, not use innovation as an explanation for progress (since as you point out, that seems merely tautological or at least devoid of new information).

The rest of your comment I find harder to follow. I hope you agree that disasters from natural causes such as floods or meteor storms qualify as real disasters. Game of Thrones is not a realistic depiction of human morality, being focused on the grim and dark. It is especially not a realistic depiction of history. The Malthus-trap point is hopefully irrelevant once we agree that innovation should indeed not be used as explanation, but rather explored as a consequence. Otherwise I really did not understand it (but please do clarify!).

I wasn’t trying to argue anything in particular, I’m just using comments as a notebook to keep track of my own thoughts. I’m sorry if it sounded like I was trying to start an argument.

Thank you for the article! In my opinion, one of the main issues is that it does not seem to explain how the Eastern part of the Empire survived.

Rome was never economically self-sufficient. The city of Rome was a sink that absorbed food and products from the provinces, and produced nothing. The millions of inhabitants of Italy could survive only thanks to the subjugated provinces of the Empire.

Other areas of the Empire, notably Egypt and Gaul, were self-sufficient. In particular, Egypt was the main exporter of manufactured good (Roman travelers to Alexandria usually lamented the fact that the local inhabitant were greedy and always busy making money). In general, the Eastern part of the Empire was much richer than the West, was more urbanized, and had many more ancient and complex local administrative institutions.

When the Empire split between a Western and a Eastern half in the IV century, the Western part was in serious trouble. The only relevant food-exporting provinces left to the Western Empire was Africa. When Africa was lost, the Empire quickly fell. On the contrary, the fall of the Western Empire had no dramatic consequences on the Eastern Empire (ok, it was a big export market loss, which probably contributed a lot to the social tensions and the riots of the Justianan era; but a crisis due to a lack of an export market for your manufactured goods is way better than a crisis due to a lack of food to import).

------

As concerns your chart of civilizations moving in the north, in my opinion this is only the result of a bias: we learn in school about the civilizations more relevant to our history. I do not buy your thesis that the intensive agricolture drove the rise and fall of the civilizations:

Ptolemaic Egypt had an estimated population of about 8 millions of inhabitants, if I recall correctly. This is a great increase with respect to Ancient Egypt, and it was largely made possible by improvement in agricolture (not only plough, but irrigation and better agronomical techniques). This is after the “civilization hot spot” moved north of Egypt in your scheme—I am not sure if this count as a point for or against your model.

I have not the time now to look for estimations of the Roman population through history, but (if you trust my half-educated guess) I do not expect a demographic boom to have took place after the Roman conquest. The Roman Empire was forged by conquest, killings and enslavements. In The Economic and Social History of the Hellenistic World (a bit aged, but highly recommended!), Rostovtzeff speaks on the contrary of “race suicide” describing the demographic decline of Greece in the II and I century BCE. The parts of the Empire that were already civilized before the Roman conquest (namely Greece and the Near East), already had infrastructures and institututions before the Romans, which were ofted of superior quality (example: the celebrated Roman aqueducts worked by gravity, while e.g. the city of Pergamon in 180 BCE had watertight metal pipes which lifted water over a difference of altitude of >100 m. Also, the Roman aqueducts were designed by Greek slave engineers; the Romans never learned to project them on their own. Once the last educated Greek slaves dies, they could not buy anymore aqueducts. I hope that this specific example clarifies the general trend); and on top of this, after the Roman conquest, they also had to feed an economically parasite overlord. So I do not expect the population of the Eastern part of the empire to have substantially risen durin Roman rule (also Wikipedia says that it decreased, but I did not verify the sources). On the contrary, the population did probably rise (after the initial mass slaughters) in the formerly sparsely populated regions of Northern Western Europe; but these are also the provinces that in your chart became more relavant for civilization after the fall of Rome, so this does not seem to advance your theory.

There is no way in which Charlemagne’s empire was more relevant than the Umayyad Caliphate in 800 AD , in any reasonable “civilization” metric.

Southern Europe was economically more developed than northern europe until the XVI century, and while the causes that reversed this pattern are object of debate among scholars (I recommend this paper), I do not recall seeing soil depletion as a proposed cause (instead, the shift in global trade route and the centralized governments likely played a role).

Thanks for the long reply!

You’re describing a lot of local contrasts. The city of Rome vs the provinces. The Western Rome Empire vs the Eastern half. Charlemagne vs the Umayyads. While certainly interesting and worthy of discussion, the trends I try to perceive and explain happen on more of a global level.

Look at the shipwrecks and lead pollution graph or the social development graph from the first article. I’m pretty sure the lead pollution was measured from ice cores in Greenland. It’s pollution from all of Europe (and perhaps even more distant), not just pollution in the vicinity of the city of Rome. It was barely existant in 600BC, peaks enormously in the first century AD, and it’s at ~10% of its former peak in 600AD.

The social development graph follows the most advanced civilization in either the western or eastern half of Afro-Eurasia. If one culture declines and is taken over by another, it switches. Look at this example of Western maximum settlement sizes:

100 CE: Rome, 1,000,000; 9.36 points

200 CE: Rome, 1,000,000; 9.36 points

300 CE: Rome, 800,000; 7.49 points

400 CE: Rome, 800,000; 7.49 points

500 CE: Constantinople, 450,000; 4.23 points

600 CE: Constantinople, 150,000; 1.41 points

700 CE: Constantinople, 125,000; 1.17 points

800 CE: Baghdad, 175,000; 1.64 points

900 CE: Cordoba, 175,000; 1.64 points

1000 CE: Cordoba, 200,000; 1.87 points

1100 CE: Constantinople, 250,000; 2.34 points

1200 CE: Baghdad, Cairo, Constantinople, 250,000; 2.34 points

1300 CE: Cairo, 400,000; 3.75 points

1400 CE: Cairo, 125,000; 1.17 points

1500 CE: Cairo, 400,000; 3.75 points

1600 CE: Constantinople, 400,000; 3.75 points

1700 CE: London and Constantinople, 600,000; 5.62 points

1800 CE: London, 900,000; 8.43 points

1900 CE: London, 6,600,000; 61.8 points

2000 CE: New York, 16,700,000; 156.37 points

As you suggest, in 800 AD, the author is looking at the Umayyads and not Charlemagne. While they quantatively exceed Europe in that time period, they don’t exceed ‘peak-Rome’ in these statistics.

I’m not trying to say that Rome was inherently awesome and good and virtuous. It’s probably true that they were parasitic and exploitative. But it seems that the first century AD certainly was an era of unprecedented economic activity in the West. Trade and pollution and building happened on a huge scale. And this just.… vanished. Of course, there were still large countries and empires, some even bearing some of the titles of the former Roman Empire. There were still cities and economic activity and inventions. But the scale of the first century AD, and a lot of specific Roman practices like concrete, large public bathhouses and the mass use of brick, seems to have completely disappeared until the Industrial Revolution.

Yes, the lead pollution was measured with arctic ice; this is the original paper. The authors belive that the peak in the eraly Imperial era was mainly caused by the Rio Tinto ore mines (so yes, it is pollution from all Europe, but mainly from Spain).

I agree with your main point that the first century BCE and the first century CE were a peak of economic developement of the ancient world (as shown by the graphs); I think that this is not in contradiction with what I am saying. In the first century BCE, many of the Roman provinces were of recent conquests, with much of their local institutions and know-how intact. Think of the Antikythera mechanism, which was built around the first century BCE.

In the III century, nobody could have built nothing even remotely similar to the Antikythera mechanism. If I understand correctly your overall thesis, this was because a shortage of fuel led to a simiplification of the society, so that the supply chain for building an Antikythera mechanism was not anymore feasible. But the main bottleneck in building an Antikythera mechanism is not the wood that you need to burn in making the cogs and the gears; the main bottleneck are the mathematical and mechanical knowledge necessary to design it, and the artigianal expertise needed to build its components. The Romans did not care about any of it. No respectable Roman learned mathematics: it was a suspiciously Greek, nerdy thing, unsuited to the practical Roman spirit. The first Latin translation of Euclid’s Elements was written in the Renaissance. I am sure that this played a significant role in the loss of mechanical technology after the first century (and, if you believe that mechanical technology was significant for the Hellenistic economy (a point about which scholars disagree), also played a role in the economic decline).

The vanishing of the economy was not, in my view, an unavoidable effect of resource depletion, but it was a consequence of the specific political and economical situation in the Imperial age. The Greek and Hellenistic states kept a complex and viable economy for much more centuries than “peak-Rome”, with much fewer resources to start with (a narrow bucket, in your metaphor). Byzantium/Costantinople/Istanbul was there before “peak-Rome”, and continued to be one of the main cities of the world long after Rome. How come Costantinople did not fill its bucket in 2000 years, while Rome (with access to a much wider bucket) did it in a few centuries? (maybe I am misrepresenting or excessively simplifying your view; I apologize if so)

Do you see a clear pattern in the sequence Rome → Costantinople → Baghdad → Cordoba → Costantinople → Cairo → Costantinople → London → New York? How does this succession fit in your model?

I don’t necessarily agree with your depiction of the Romans as being “parasitic”. Just because they did not produce food, does not mean that they were not valued.

The Romans were interested in math, its just that most of them weren’t located in Italia. Just look at the various mathematicians who lived in Alexandria, Athens, or Constantinople, and invented the fields of trigonometry (among others).

Rome had almost completely absorbed Greek culture and academics, to the point where many prominent Romans often read and wrote in Greek. Unless you were Cato the Censor, you almost certainly learned Greek math, its just that if you wanted to practice it full time, you would live in the east (and spoke Greek). Especially after the 4th century, when the focus of the Empire shifted to the East anyways.

Also, the Romans heavily benefited the economy of the Greeks. An interconnected empire meant that Greek goods (such as amphorae, pottery, or other luxury items) could be traded anywhere in the empire, with only the nominal port taxes placed on it by the Empire. Also Rome wasn’t militarily occupying the East either, since the entirety of it was governed by the Senate (except Syria, Mesopotamia, and Armenia).

The immediate cause for the fact that “lead pollution in 200 AD was lower than lead pollution in 1 AD” is that “the extraction from Rio Tinto mines in 200 AD was lower than the extraction from Rio Tinto mines in 1 AD”. Now, according to Diodorus Siculus (Bibliotheca historica, V, xxxvi-xxxvi), the Carthaginians used mechanical and hydraulic technology for exploiting the Rio Tinto mines (they probably also employed chemical acids). According to Bromehead, this impressive technology was initially expanded by the Roman conquerors; but eventually the Romans switched to using large masses of slaves (as described by Pliny), becuse they were not able to keep the mechanical drainage systems running.

By “parasitic” I mean that Rome imported a lot and exported no products; but you are right in pointing out that the “military services” exported by Rome (and the common market) had probably a great economic value for the provinces. Still, do you agree that Rome was not self-sufficient?

I challenge you to name one mathematical treatise, written between 100 BC and 500 AD, which is on the same tier as the work by Archimedes, Ipparchus or Apollonius (the difference in quality is so big that it is not subjective).

If you with “Roman” mean “anyone living in the Roman Empire” then yes, some Roman were interested in higher math. But the mathematics in the Imperial age was a shadow of what mathematics was before the Roman conquest. Trigonometry was first developed in Alexandria when Egypt was an independent Hellenistic kingdom; then in 146 BC the Romans installed a puppet king in Egypt, who proceeded to persecute the Greek èlites and to annihilate every intellectual opposition (he literally appointed a spearmen officer as the new director of the Library of Alexandria). To escape the persecution, many Greek intellectuals (including the mathematicians) escaped; some of them went to India, where they founded a school which continued to develop trigonometry (sine and cosine were first defined in India).

It is true that some (not so many) Romans learned greek maths even well into the V century (for example, emperor Procopius Anthemius studied under Proclus), but all the mathematics of the Imperial age consists of commentaries and collections of previous results. Sometimes they are brilliant commentaries, but still commentaries.

I do not have much knowledge about the Imperial age, and maybe this was true in 100-200 AD, but it was definitely not true in the aftermath of the Roman conquest (see Rostovtzeff’s books).

I would point to a different cycle to explain the fall of Rome. Set this against both the Malthusian trap theory and the (many) theories around technology. This is an institutional story.

One of the key problems that the Roman state failed to solve was that of who rules. The Republic was semi-successful at this. It used public recognition and generational advancement in social class as its main methods of controlling elites. This ultimately failed after the Carthaginian wars eliminated the external enemy that kept internal politicking in check. At this point you see a continuous cycle of ambitious elites conquering new territories in the name of Rome and — this is critical — enriching themselves massively and using that fortune to control the Roman state. This led to the civil wars. Ultimately, Octavian triumphed — to my mind, he was the best that Rome could hope for in the circumstances, but he did not really fix the core problem.

After Augustus, the problem became more specific: the succession. The civil wars had shown that the way to control the Roman state was the control armies. Much of later Roman history is essentially a story of charismatic generals fighting for control of the state. It is the interludes in that story that are most important, though. These are when some great general prevails and stays in office long enough to carry out major reforms. Think Diocletian and Constantine.

History books seem to love these “reforms.” Economists hate them. These reforms — unlike those of Augustus — were entirely about capturing more resources for the state, so that the victorious general and his descendants would be better able to fend off competitors. But even the best of Roman’s economy did not produce massive surpluses. So extracting more was difficult. Near the end, the cost of empire was greater for taxpayers than the benefits. This explains why laws would literally mandate that every son follow his father’s occupation using his father’s property: so that the tax man would know from whom to collect. This eventually becomes feudal serfdom, where peasants were tied to the land.

In a setting where private initiative is so burdened with crushing taxation and repressive regulation, is it a surprise that economic growth reverses or that technological innovation becomes limited to agriculture?

I think that this story has more explanatory power than the energy-constraint story does. But it might compound the energy-constraint story. One of the fundamental problems with seeing energy constraint as the empire-killer is that scarcity of a resource should drive up its price. That should incentivize lots of interesting behaviors: long-distance trade, product substitution, process substitutions for technologies that use less of the resource, etc. We see this in the industrial age’s move from charcoal to coal to oil to electricity. We don’t see that in Roman times. Why? Perhaps because the central government fixed the prices of everything so that it would be easier to collect taxes. If the price of charcoal doesn’t increase when supply decreases, we miss out on all of the incentives that a freer market would have brought.

So governing institutions are a key component of why Rome fell, because they caused a ratchet effect of ever-increasing tax and regulatory burdens.

This causes me worry about modern politics. On a precautionary principle, it seems to me that we should look askance at the ever-increasing regulatory burdens on business. If they cause civilization to be less effective at producing technology that can save civilization from whatever would cause its fall (asteroid, supervolcano, disease, global warming, whatever), that seems like a bad deal. The fact that, after a fall from civilization, humanity cannot climb the same ladder it did before because it has exhausted all surface-level minerals means that —unlike Rome — this is probably our last shot at assuring super-long-term survival of the human species. So I’d prefer less regulation that we currently endure.

I should note that my final conclusion highly correlates with my priors, so is suspect.

While the lack of fuel was a serious concern to the Romans (even during the time of Augustus), I don’t think either the population pressures or the lack of fuel had much of an effect on the decline of the Empire.

After the 3rd century, Rome was more likely to face under population than overpopulation. It was estimated that the Crisis of the 3rd Century led to the deaths of about 1⁄3 of the Empire. Afterwards, (particularly in the West) the severe lack of people led to the development of the patronage system. That was one of the reasons why Rome couldn’t defeat Alaric in 410, they had no available people.

Also, for the most part, Rome was “full” even during the peak of the Empire. For the most empty provinces, Gaul and Hispania, they were empty not due to the lack of people, but due to the lack of arable land. The technology to start tilling the hard soils of northern Gaul wouldn’t be invented until the 10th century. So the late Empire wouldn’t have faced any more population pressures than the Empire of Claudius or Nero.

And finally, the lack of fuel was also a problem during the peak of the Empire. I’ve once heard (though I don’t have a source) that much of the German economy was selling fuel to the Romans circa 100CE. But besides that, the Romans had other alternatives to wood, such as how coal was often used by blacksmiths.

Oh, also I wouldn’t say that history has “moved” north overtime, just that the history of the predominant “western” empire has. If looking at the most powerful and/or sophisticated state overtime, the focus of history would constantly move between Egypt, Anatolia, Persia, Northern India, and Southern China for most of history. I think the main western empire has moved overtime simply because it can’t go south, west, or east (because of the Sahara, Atlantic, and because if it went East, it wouldn’t be considered western anymore).

The European wars of religion included among others the Thirty Years War which killed one-third of the German population. It’s mentioned as a period that caused a lot of human suffering, but not as something that seriously harmed the long-term development of Europe. To the contrary, this happened during Europe’s ascendancy as a global superpower. Crisis, war and mismanagement is certain in nearly all periods of human history. They’re not sufficient causes of long-term decline.

“Full”, “empty” and “population pressure” are very relative terms. New technological inventions, new systems of agriculture and new organizational forms constantly change the balance. That makes it very hard to assess the actually “felt” pressure at a certain moment in time.

I’ve heard that some coal was used by Romans, but also that it was always a very niche activity. Do you have sources about coal being used by blacksmiths ‘often’?

As the title states, I don’t think “progress” existed (exists?). Not as a monolithic thing that simultaneously boosts population size, population density, economic activity, individual well-being, intellectual development, real-world power/dominance/influence and cultural legacy. Think of the internet today. 20⁄25 years ago, it was a niche activity for highly educated, relatively wealthy tech experts. Nowadays, it’s used by the masses. The average IQ of the average internet user has probably declined significantly. Better technology and years of development have given us new possibilities; tech monopolies and bad habits like declining attention spans and polarization have made other things worse. The internet of 2021 is not superior or inferior to the internet of 2001 in all aspects.

I believe the Europe of 1000AD was significantly more densely populated than the Roman Europe of 1AD (or 300AD). This led to fuel scarcity and an enormous decline in fuel-intensive luxuries like bathhouses, concrete, bricks and roof tiles. I also believe an ever increasing population pressure (and probably declining standards of living for many individuals!) was a vital trigger for the Industrial Revolution many centuries later. It was the best of times, it was the worst of times. That makes it really difficult to talk about states being ’sophisticated”.