Long-time lurker (c. 2013), recent poster. I also write on the EA Forum.

Mo Putera

One subsubgenre of writing I like is the stress-testing of a field’s cutting-edge methods by applying it to another field, and seeing how much knowledge and insight the methods recapitulate and also what else we learn from the exercise. Sometimes this takes the form of parables, like Scott Alexander’s story of the benevolent aliens trying to understand Earth’s global economy from orbit and intervening with crude methods (like materialising a billion barrels of oil on the White House lawn to solve a recession hypothesised to be caused by an oil shortage) to intuition-pump the current state of psychiatry and the frame of thinking of human minds as dynamical systems. Sometimes they’re papers, like Eric Jonas and Konrad P. Kording’s Could a Neuroscientist Understand a Microprocessor? (they conclude that no, regardless of the amount of data, “current analytic approaches in neuroscience may fall short of producing meaningful understanding of neural systems” — “the approaches reveal interesting structure in the data but do not meaningfully describe the hierarchy of information processing in the microprocessor”). Unfortunately I don’t know of any other good examples.

I’m not sure about Friston’s stuff to be honest.

But Watts lists a whole bunch of papers in support of the blindsight idea, contra Seth’s claim — to quote Watts:

“In fact, the nonconscious mind usually works so well on its own that it actually employs a gatekeeper in the anterious cingulate cortex to do nothing but prevent the conscious self from interfering in daily operations”

footnotes: Matsumoto, K., and K. Tanaka. 2004. Conflict and Cognitive Control. Science 303: 969-970; 113 Kerns, J.G., et al. 2004. Anterior Cingulate Conflict Monitoring and Adjustments in Control. Science 303: 1023-1026; 114 Petersen, S.E. et al. 1998. The effects of practice on the functional anatomy of task performance. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 95: 853-860

“Compared to nonconscious processing, self-awareness is slow and expensive”

footnote: Matsumoto and Tanaka above

“The cost of high intelligence has even been demonstrated by experiments in which smart fruit flies lose out to dumb ones when competing for food”

footnote: Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B (DOI 10.1098/rspb.2003.2548)

“By way of comparison, consider the complex, lightning-fast calculations of savantes; those abilities are noncognitive, and there is evidence that they owe their superfunctionality not to any overarching integration of mental processes but due to relative neurological fragmentation”

footnotes: Treffert, D.A., and G.L. Wallace. 2004. Islands of genius. Scientific American 14: 14-23; Anonymous., 2004. Autism: making the connection. The Economist, 372(8387): 66

“Even if sentient and nonsentient processes were equally efficient, the conscious awareness of visceral stimuli—by its very nature— distracts the individual from other threats and opportunities in its environment”

footnote: Wegner, D.M. 1994. Ironic processes of mental control. Psychol. Rev. 101: 34-52

“Chimpanzees have a higher brain-to-body ratio than orangutans, yet orangs consistently recognise themselves in mirrors while chimps do so only half the time”

footnotes: Aiello, L., and C. Dean. 1990. An introduction to human evolutionary anatomy. Academic Press, London; 123 Gallup, G.G. (Jr.). 1997. On the rise and fall of self-conception in primates. In The Self Across Psychology— self-recognition, self-awareness, and the Self Concept. Annals of the NY Acad. Sci. 818:4-17

“it turns out that the unconscious mind is better at making complex decisions than is the conscious mind”

footnote: Dijksterhuis, A., et al. 2006. Science 311:1005-1007

(I’m also reminded of DFW’s How Tracy Austin Broke My Heart.)

To be clear I’m not arguing that “look at all these sources, it must be true!” (we know that kind of argument doesn’t work). I’m hoping for somewhat more object-level counterarguments is all, or perhaps a better reason to dismiss them as being misguided (or to dismiss the picture Watts paints using them) than what Seth gestured at. I’m guessing he meant “complex general cognition” to point to something other than pure raw problem-solving performance.

Thanks, is there anything you can point me to for further reading, whether by you or others?

Peter Watts is working with Neill Blomkamp to adapt his novel Blindsight into an 8-10-episode series:

“I can at least say the project exists, now: I’m about to start writing an episodic treatment for an 8-10-episode series adaptation of my novel Blindsight.

“Neill and I have had a long and tortured history with that property. When he first expressed interest, the rights were tied up with a third party. We almost made it work regardless; Neill was initially interested in doing a movie that wasn’t set in the Blindsight universe at all, but which merely used the speculative biology I’d invented to justify the existence of Blindsight’s vampires. “Sicario with Vampires” was Neill’s elevator pitch, and as chance would have it the guys who had the rights back then had forgotten to renew them. So we just hunkered quietly until those rights expired, and the recently-rights-holding parties said Oh my goodness we thought we’d renewed those already can we have them back? And I said, Sure; but you gotta carve out this little IP exclusion on the biology so Neill can do his vampire thing.

“It seemed like a good idea at the time. It was good idea, dammit. We got the carve-out and everything. But then one of innumerable dead-eyed suits didn’t think it was explicit enough, and the rights-holders started messing us around, and what looked like a done deal turned to ash. We lost a year or more on that account.

“But eventually the rights expired again, for good this time. And there was Neill, waiting patiently in the shadows to pounce. So now he’s developing both his Sicario-with-vampires movie and an actual Blindsight adaptation. I should probably keep the current status of those projects private for the time being. Neill’s cool with me revealing the existence of the Blindsight adaptation at least, and he’s long-since let the cat out of the bag for his vampire movie (although that was with some guy called Joe Rogan, don’t know how many people listen to him). But the stage of gestation, casting, and all those granular nuts and bolts are probably best kept under wraps for the moment.

“What I can say, though, is that it feels as though the book has been stuck in option limbo forever, never even made it to Development Hell, unless you count a couple of abortive screenplays. And for the first time, I feel like something’s actually happening. Stay tuned.”

When I first read Blindsight over a decade ago it blew my brains clean out of my skull. I’m cautiously optimistic about the upcoming series, we’ll see…

There’s a lot of fun stuff in Anders Sandberg’s 1999 paper The Physics of Information Processing Superobjects: Daily Life Among the Jupiter Brains. One particularly vivid detail was (essentially) how the square-cube law imposes itself upon Jupiter brain architecture by forcing >99.9% of volume to be comprised of comms links between compute nodes, even after assuming a “small-world” network structure allowing sparse connectivity between arbitrarily chosen nodes by having them be connected by a short series of intermediary links with only 1% of links being long-range.

For this particular case (“Zeus”), a 9,000 km sphere of nearly solid diamondoid consisting mainly of reversible quantum dot circuits and molecular storage systems surrounded by a concentric shield protecting it from radiation and holding radiators to dissipate heat into space, with energy provided by fusion reactors distributed outside the shield, only the top 1.35 km layer is compute + memory (a lot thinner comparatively than the Earth’s crust), and the rest of the interior is optical comms links. Sandberg calls this the “cortex model”.

In a sense this shouldn’t be surprising since both brains and current semiconductor chips are mostly interconnect by volume already, but a 1.35 km thick layer of compute + memory encompassing a 9,000 km sphere of optical comms links seems a lot more like a balloon to me than anything, so from now on I’ll probably think of them as Jupiter balloons.

Venkatesh Rao’s recent newsletter article Terms of Centaur Service caught my eye for his professed joy of AI-assisted writing, both nonfiction and fiction:

In the last couple of weeks, I’ve gotten into a groove with AI-assisted writing, as you may have noticed, and I am really enjoying it. … The AI element in my writing has gotten serious, and I think is here to stay. …

On the writing side, when I have a productive prompting session, not only does the output feel information dense for the audience, it feels information dense for me.

An example of this kind of essay is one I posted last week, on a memory-access-boundary understanding of what intelligence is. This was an essay I generated that I got value out of reading. And it didn’t feel like a simple case of “thinking through writing.” There’s stuff in here contributed by ChatGPT that I didn’t know or realize even subconsciously, even though I’ve been consulting for 13 years in the semiconductor industry.

Generated text having elements new to even the prompter is a real benefit, especially with fiction. I wrote a bit of fiction last week that will be published in Protocolized tomorrow that was so much fun, I went back and re-read it twice. This is something I never do with m own writing. By the time I ship an unassisted piece of writing, I’m generally sick of it.

AI-assisted writing allows you to have your cake and eat it too. The pleasure of the creative process, and the pleasure of reading. That’s in fact a test of good slop — do you feel like reading it?

I think this made an impression on me because Venkat’s joy contrasts so much to many people’s criticism of Sam Altman’s recent tweet re: their new creative fiction model’s completion to the prompt “Please write a metafictional literary short story about AI and grief”, including folks like Eliezer, who said “To be clear, I would be impressed with a dog that wrote the same story, but only because it was a dog”. I liked the AI’s output quite a lot actually, more than I did Eliezer’s (and I loved HPMOR so I should be selected for Eliezer-fiction-bias), and I found myself agreeing with Roon’s pushback to him.

Although Roshan’s remark that “AI fiction seems to be in the habit of being interesting only to the person who prompted it” does give me pause. While this doesn’t seem to be true in the AI vs Eliezer comparison specifically, I do find plausible a hyperpersonalisation-driven near-future where AI fiction becomes superstimuli-level interesting only to the prompter. But I find the contra scenario plausible too. Not sure where I land here.

There’s a version of this that might make sense to you, at least if what Scott Alexander wrote here resonates:

I’m an expert on Nietzsche (I’ve read some of his books), but not a world-leading expert (I didn’t understand them). And one of the parts I didn’t understand was the psychological appeal of all this. So you’re Caesar, you’re an amazing general, and you totally wipe the floor with the Gauls. You’re a glorious military genius and will be celebrated forever in song. So . . . what? Is beating other people an end in itself? I don’t know, I guess this is how it works in sports6. But I’ve never found sports too interesting either. Also, if you defeat the Gallic armies enough times, you might find yourself ruling Gaul and making decisions about its future. Don’t you need some kind of lodestar beyond “I really like beating people”? Doesn’t that have to be something about leaving the world a better place than you found it?

Admittedly altruism also has some of this same problem. Auden said that “God put us on Earth to help others; what the others are here for, I don’t know.” At some point altruism has to bottom out in something other than altruism. Otherwise it’s all a Ponzi scheme, just people saving meaningless lives for no reason until the last life is saved and it all collapses.

I have no real answer to this question—which, in case you missed it, is “what is the meaning of life?” But I do really enjoy playing Civilization IV. And the basic structure of Civilization IV is “you mine resources, so you can build units, so you can conquer territory, so you can mine more resources, so you can build more units, so you can conquer more territory”. There are sidequests that make it less obvious. And you can eventually win by completing the tech tree (he who has ears to hear, let him listen). But the basic structure is A → B → C → A → B → C. And it’s really fun! If there’s enough bright colors, shiny toys, razor-edge battles, and risk of failure, then the kind of ratchet-y-ness of it all, the spiral where you’re doing the same things but in a bigger way each time, turns into a virtuous repetition, repetitive only in the same sense as a poem, or a melody, or the cycle of generations.

The closest I can get to the meaning of life is one of these repetitive melodies. I want to be happy so I can be strong. I want to be strong so I can be helpful. I want to be helpful because it makes me happy.

I want to help other people in order to exalt and glorify civilization. I want to exalt and glorify civilization so it can make people happy. I want them to be happy so they can be strong. I want them to be strong so they can exalt and glorify civilization. I want to exalt and glorify civilization in order to help other people.

I want to create great art to make other people happy. I want them to be happy so they can be strong. I want them to be strong so they can exalt and glorify civilization. I want to exalt and glorify civilization so it can create more great art.

I want to have children so they can be happy. I want them to be happy so they can be strong. I want them to be strong so they can raise more children. I want them to raise more children so they can exalt and glorify civilization. I want to exalt and glorify civilization so it can help more people. I want to help people so they can have more children. I want them to have children so they can be happy.

Maybe at some point there’s a hidden offramp marked “TERMINAL VALUE”. But it will be many more cycles around the spiral before I find it, and the trip itself is pleasant enough.

In my corner of the world, anyone who hears “A4” thinks of this:

The OECD working paper Miracle or Myth? Assessing the macroeconomic productivity gains from Artificial Intelligence, published quite recently (Nov 2024), is strange to skim-read: its authors estimate just 0.24-0.62 percentage points annual aggregate TFP growth (0.36-0.93 pp. for labour productivity) over a 10-year horizon, depending on scenario, using a “novel micro-to-macro framework” that combines “existing estimates of micro-level performance gains with evidence on the exposure of activities to AI and likely future adoption rates, relying on a multi-sector general equilibrium model with input-output linkages to aggregate the effects”.

I checked it out both to get a more gears-y sense of how AI might transform the economy soon and to get an outside-my-bubble data-grounded sense of what domain experts think, but 0.24-0.62 pp TFP growth and 0.36-0.93 pp labor seem so low (relative to say L Rudolf L’s history of the future, let alone AI 2027) that I’m tempted to just dismiss them as not really internalising what AGI means. A few things prevent me from dismissing them: it seems epistemically unvirtuous to do so, they do predicate their forecasts on a lot of empirical data, anecdotes like lc’s recent AI progress feeling mostly like bullshit (although my own experience is closer to this), and (boring technical loophole) they may end up being right in the sense that real GDP would still look smooth even after a massive jump in AI, due to GDP growth being calculated based on post-jump prices deflating the impact of the most-revolutionised goods & services.

Why so low? They have 3 main scenarios (low adoption, high adoption and expanded capabilities, and latter plus adjustment frictions and uneven gains across sectors, which I take to be their best guess), plus 2 additional scenarios with “more extreme assumptions” (large and concentrated gains in most exposed sectors, which they think are ICT services, finance, professional services and publishing and media, and AI + robots, which is my own best guess); all scenarios assume just +30% micro-level gains from AI, except the concentrated gains one which assumes 100% gains in the 4 most-exposed sectors. From this low starting point they effectively discount further by factors like Acemoglu (2024)’s estimate that 20% of US labor tasks are exposed to AI (ranging from 11% in agriculture to ~50% in IT and finance), exposure to robots (which seems inversely related to AI exposure, e.g. ~85% in agriculture vs < 10% in IT and finance), 23-40% AI adoption rates, restricted factor allocation across sectors, inelastic demand, Baumol effect kicking in for scenarios with uneven cross-sectoral gains, etc.

Why just +30% micro-level gain from AI? They explain in section 2.2.1; to my surprise they’re already being more generous than the authors they quote, but as I’d guessed they just didn’t bother to predict whether micro-level gains would improve over time at all:

Briggs and Kodnani (2023) rely on firm-level studies which estimate an average gain of about 2.6% additional annual growth in workers’ productivity, leading to about a 30% productivity boost over 10 years. Acemoglu (2024) uses a different approach and start from worker-level performance gains in specific tasks, restricted to recent Generative AI applications. Nevertheless, these imply a similar magnitude, roughly 30% increase in performance, which they assume to materialise over the span of 10 years.

However, they interpret these gains as pertaining only to reducing labour costs, hence when computing aggregate productivity gains, they downscale the micro gains by the labour share. In contrast, we take the micro studies as measuring increases in total factor productivity since we interpret their documented time savings to apply to the combined use of labour and capital. For example, we argue that studies showing that coders complete coding tasks faster with the help of AI are more easily interpretable as an increase in the joint productivity of labour and capital (computers, office space, etc.) rather than as cost savings achieved only through the replacement of labour.

To obtain micro-level gains for workers performing specific tasks with the help of AI, this paper relies on the literature review conducted by Filippucci et al. (2024). … The point estimates indicate that the effect of AI tools on worker performance in specific tasks range from 14% (in customer service assistance) to 56% (in coding), estimated with varying degrees of precision (captured by different sizes of confidence intervals). We will assume a baseline effect of 30%, which is around the average level of gains in tasks where estimates have high precision.

Why not at least try to forecast micro-level gains improvement over the next 10 years?

Finally, our strategy aims at studying the possible future impact of current AI capabilities, considering also a few additional capabilities that can be integrated into our framework by relying on existing estimates (AI integration with additional software based on Eloundou et al, 2024; integration with robotics technologies). In addition, it is clearly possible that new types of AI architectures will eliminate some of the current important shortcomings of Generative AI – inaccuracies or invented responses, “hallucinations” – or improve further on the capabilities, perhaps in combination with other existing or emerging technologies, enabling larger gains (or more spread-out gains outside these knowledge intensive services tasks; see next subsection). However, it is still too early to assess whether and to what extent these emerging real world applications can be expected.

Ah, okay then.

What about that 23-40% AI adoption rate forecast over the next 10 years, isn’t that too conservative?

To choose realistic AI adoption rates over our horizon, we consider the speed at which previous major GPTs (electricity, personal computers, internet) were adopted by firms. Based on the historical evidence, we consider two possible adoption rates over the next decade: 23% and 40% (Figure 6). The lower adoption scenario is in line with the adoption path of electricity and with assumptions used in the previous literature about the degree of cost-effective adoption of a specific AI technology – computer vision or image recognition – in 10 years (Svanberg et al., 2024; also adopted by Acemoglu, 2024). The higher adoption scenario is in line with the adoption path of digital technologies in the workplace such as computers and internet. It is also compatible with a more optimistic adoption scenario based on a faster improvement in the cost-effectiveness of computer vision in the paper by Svanberg et al. (2024).

On the one hand, the assumption of a 40% adoption rate in 10 years can still be seen as somewhat conservative, since AI might have a quicker adoption rate than previous digital technologies, due its user-friendly nature. For example, when looking at the speed of another, also relatively user-friendly technology, the internet, its adoption by households after 10 years surpassed 50% (Figure A2 in the Annex). On the other hand, a systemic adoption of AI in the core business functions – instead of using it only in isolated, specific tasks – would still require substantial complementary investments by firms in a range of intangible assets, including data, managerial practices, and organisation (Agrawal, A., J. Gans and A. Goldfarb, 2022). These investments are costly and involve a learning-by-doing, experimental phase, which may slow down or limit adoption. Moreover, while declining production costs were a key driver of rising adoption for past technologies, there are indications that current AI services are already provided at discount prices to capture market shares, which might not be sustainable for long (see Andre et al, 2024). Finally, the pessimistic scenario might also be relevant in the case where limited reliability of AI or lack of social acceptability prevents AI adoption for specific occupations. To reflect this uncertainty, our main scenarios explore the implications of assuming either a relatively low 23% or a higher 40% future adoption rate.

I feel like they’re failing to internalise the lesson from this chart that adoption rates are accelerating over time:

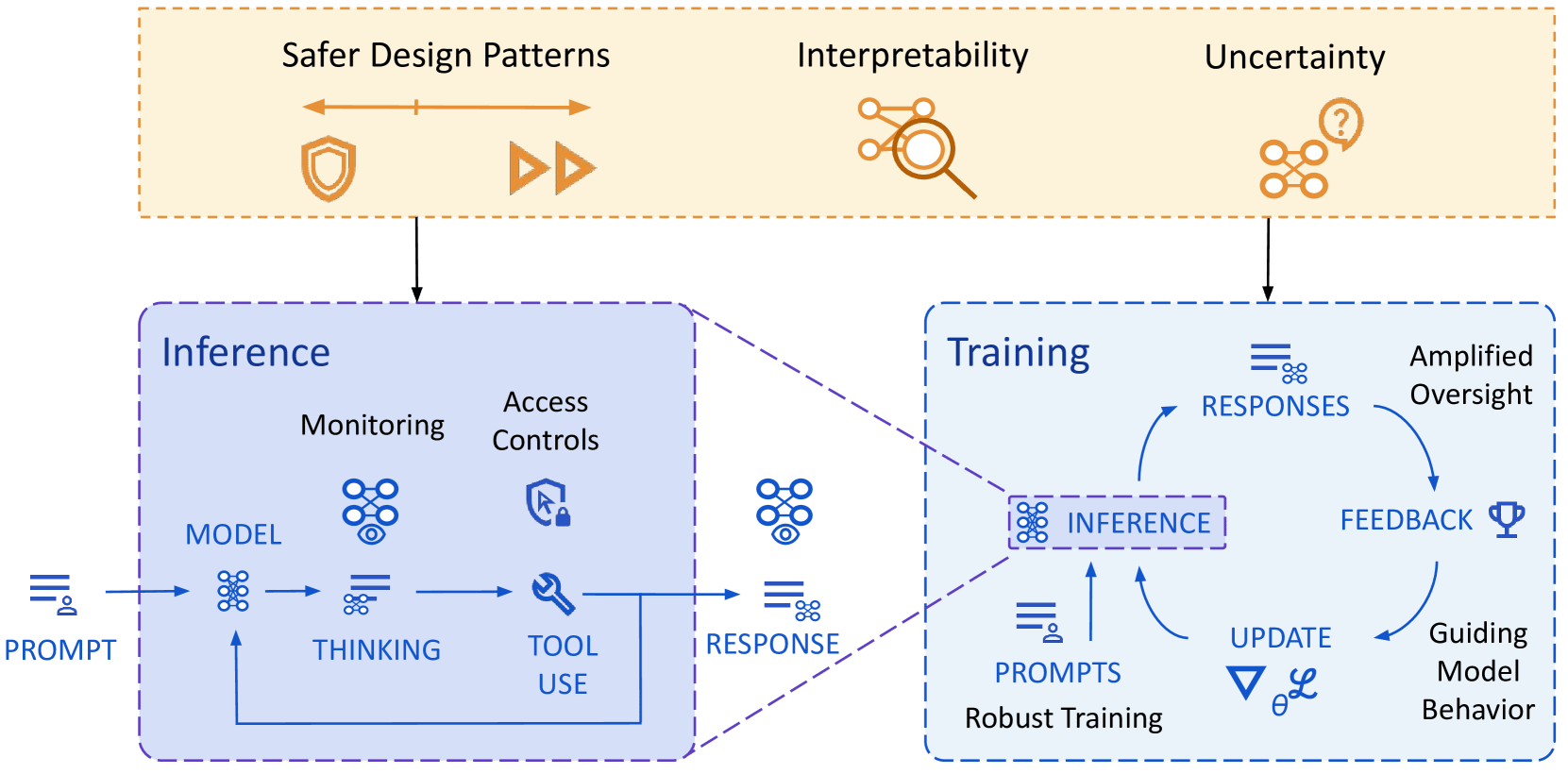

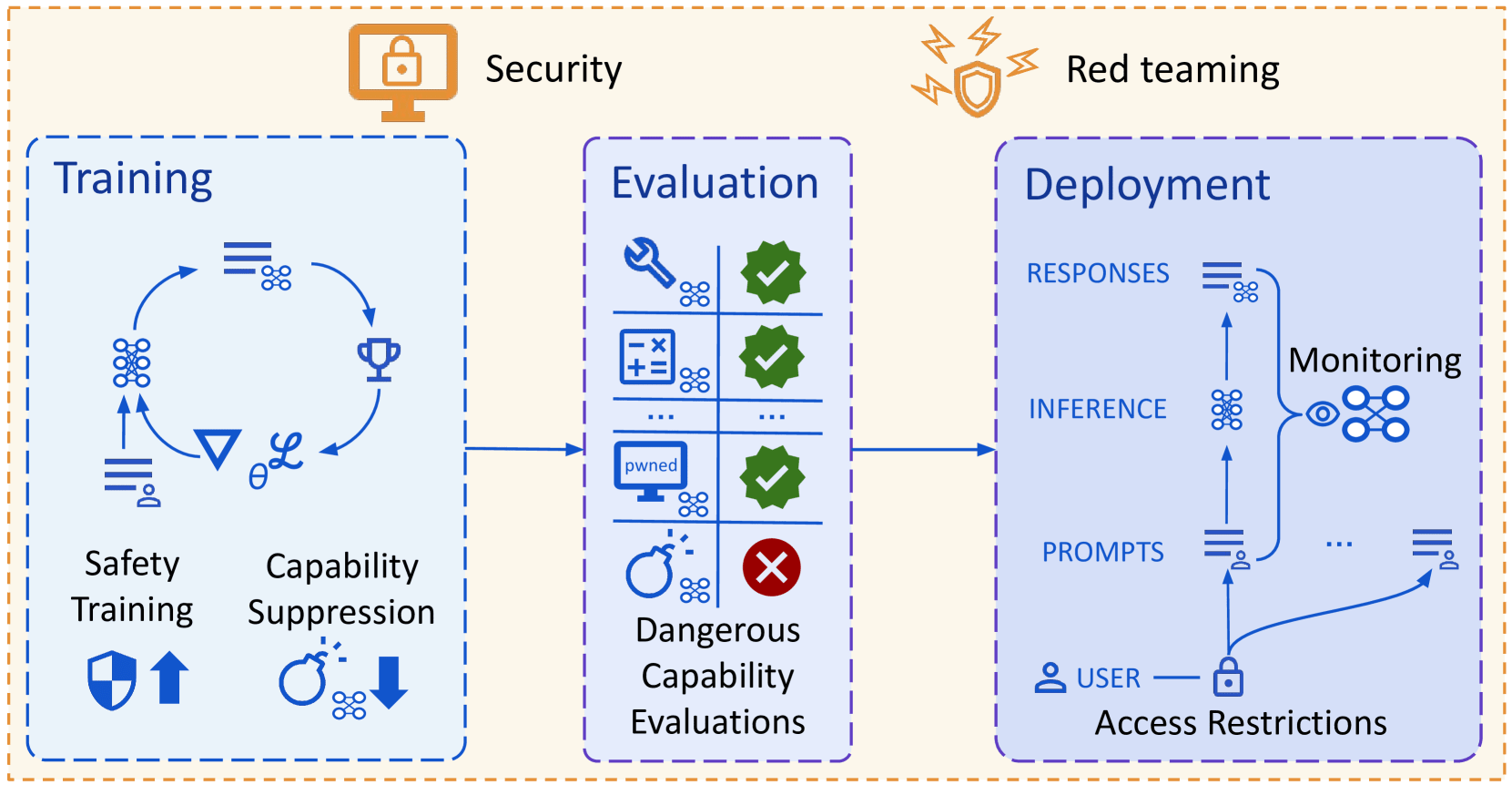

(Not a take, just pulling out infographics and quotes for future reference from the new DeepMind paper outlining their approach to technical AGI safety and security)

Overview of risk areas, grouped by factors that drive differences in mitigation approaches:

Overview of their approach to mitigating misalignment:

Overview of their approach to mitigating misuse:

Path to deceptive alignment:

How to use interpretability:

Goal Understanding v Control Confidence Concept v Algorithm (Un)supervised? How context specific? Alignment evaluations Understanding Any Concept+ Either Either FaithfulReasoning Understanding∗ Any Concept+ Supervised+ Either DebuggingFailures Understanding∗ Low Either Unsupervised+ Specific Monitoring Understanding Any Concept+ Supervised+ General Red teaming Either Low Either Unsupervised+ Specific Amplified oversight Understanding Complicated Concept Either Specific Interpretability techniques:

Technique Understanding v Control Confidence Concept v Algorithm (Un)supervised? How specific? Scalability Probing Understanding Low Concept Supervised Specific-ish Cheap Dictionary

learningBoth Low Concept Unsupervised General∗ Expensive Steering

vectorsControl Low Concept Supervised Specific-ish Cheap Training data

attributionUnderstanding Low Concept Unsupervised General∗ Expensive Auto-interp Understanding Low Concept Unsupervised General∗ Cheap Component

AttributionBoth Medium Concept Complicated Specific Cheap Circuit analysis

(causal)Understanding Medium Algorithm Complicated Specific Expensive Assorted random stuff that caught my attention:

They consider Exceptional AGI (Level 4) from Morris et al. (2023), defined as an AI system that matches or exceeds that of the 99th percentile of skilled adults on a wide range of non-physical tasks (contra the Metaculus “when AGI?” question that has diverse robotic capabilities, so their 2030 is probably an overestimate)

The irrelevance of physical limits to the paper’s scope: “By considering the construction of “the ultimate laptop”, Lloyd (2000) suggests that Moore’s law (formalized as an 18 month doubling) cannot last past 2250. Krauss and Starkman (2004) consider limits on the total computation achievable by any technological civilization in our expanding universe—this approach imposes a (looser) 600-year limit in Moore’s law. However, since we are very far from these limits, we do not expect them to have a meaningful impact on timelines to Exceptional AGI”

Structural risks are “out of scope of this paper” because they’re “a much bigger category, often with each risk requiring a bespoke approach. They are also much harder for an AI developer to address, as they often require new norms or institutions to shape powerful dynamics in the world” (although “much of the technical work discussed in this paper will also be relevant for structural risks”)

Mistakes are also out of scope because “standard safety engineering practices (e.g. testing) can drastically reduce risks, and should be similarly effective for averting AI mistakes as for human mistakes… so we believe that severe harm from AI mistakes will be significantly less likely than misuse or misalignment, and is further reducible through appropriate safety practices”

The paper focuses “primarily on techniques that can be integrated into current AI development, due to our focus on anytime approaches to safety” i.e. excludes “research bets that pay out over longer periods of time but can provide increased safety, such as agent foundations, science of deep learning, and application of formal methods to AI”

Algorithmic progress papers: “Erdil and Besiroglu (2022) sought to decompose AI progress in a way that can be attributed to the separate factors of scaling (compute, model size and data) and algorithmic innovation, and concluded that algorithmic progress doubles effective compute budgets roughly every nine months. Ho et al. (2024) further extend this approach to study algorithmic improvements in the pretraining of language models for the period of 2012 − 2023. During this period, the authors estimate that the compute required to reach a set performance threshold halved approximately every eight months”

Explosive economic growth paper: “Recent modeling by Erdil et al. (2025) that draws on empirical scaling laws and semi-endogenous growth theory and models changes in compute, automation and production supports the plausibility of very rapid growth in Gross World Product (e.g. exceeding 30% per year in 2045) when adopting parameters from empirical data, existing literature and reasoned judgment” (I’m still wondering how this will get around johnswentworth’s objection to using GDP to track this)

General competence scales smoothly with compute: “Owen (2024) find that aggregate benchmarks (BIG-Bench (Srivastava et al., 2023), MMLU (Hendrycks et al., 2020)) are predictable with up to 20 percentage points of error when extrapolating through one order of magnitude (OOM) of compute. Gadre et al. (2024) similarly find that aggregate task performance can be predicted with relatively high accuracy, predicting average top-1 error across 17 tasks to within 1 percentage point using 20× less compute than is used for the predicted model. Ruan et al. (2024) find that 8 standard downstream LLM benchmark scores across many model families are well-explained in terms of their top 3 principal components. Their first component scales smoothly across 5 OOMs of compute and many model families, suggesting that something like general competence scales smoothly with compute”

“given that total labor compensation represents over 50% of global GDP (International Labour Organisation, 2022), it is clear that the economic incentive for automation is extraordinarily large”

I agree that virtues should be thought of as trainable skills, which is also why I like David Gross’s idea of a virtue gym:

Two misconceptions sometimes cause people to give up too early on developing virtues:

that virtues are talents that some people have and other people don’t as a matter of predisposition, genetics, the grace of God, or what have you (“I’m just not a very influential / graceful / original person”), and

that having a virtue is not a matter of developing a habit but of having an opinion (e.g. I agree that creativity is good, and I try to respect the virtue of creativity that way, rather than by creating).

It’s better to think of a virtue as a skill like any other. Like juggling, it might be hard at first, it might come easier to some people than others, but almost anyone can learn to do it if they put in persistent practice.

We are creatures of habit: We create ourselves by what we practice. If we adopt habits carelessly, we risk becoming what we never intended to be. If instead we deliberate about what habits we want to cultivate, and then actually put in the work, we can become the sculptors of our own characters.

What if there were some institution like a “virtue gymnasium” in which you could work on virtues alongside others, learning at your own pace, and building a library of wisdom about how to go about it most productively? What if there were something like Toastmasters, or Alcoholics Anonymous, or the YMCA but for all of the virtues?

Conversations with LLMs could be the “home gym” equivalent I suppose.

The link in the OP explains it:

In ~2020 we witnessed the Men’s/Women’s World Cup Scandal. The US Men’s Soccer team had failed to qualify for the previous World Cup, whereas the US Women’s Soccer team had won theirs! And yet the women were paid less that season after winning than the men were paid after failing to qualify. There was Discourse.

I was in the car listening to NPR, pulling out of the parking lot of a glass supplier when my world shattered again.3 One of the NPR leftist commenters said roughly ~‘One can propose that the mens team and womens team play against each other to sort this out—’

At which point I mentally pumped my fist in the air and cheered. I had been thinking exactly this for WEEKS. I couldn’t quite understand why no one had said it! As we all know, men and women are largely undifferentiated. Soccer is a perfect example of this, because the sport doesn’t allow men to use their upper-body strength advantage at all. The one thing that makes men stand out is neutralized here, and a direct competition would put this thing to rest and humiliate all the sexists. I smiled and waited to see how the right-wing asshat would squirm out of having to endorse a match that we all knew would shut him up.

The left-wing commentator continued ’—is what one would say if one is a right-wing deplorable that just wants to laugh while humiliating those that are already oppressed. Naturally none of us would ever propose such a thing, we aren’t horrible people. Here’s what they get wrong…”

I didn’t hear any more after that, because my world had shattered again. A proponent of my side was not only admitting that the women’s team would lose badly, but that everyone knew and had always known that the women’s team would lose badly, so the only reason one would even suggest such a thing was to humiliate them.

Here I was, in my late 30s, still believing that men and women are basically the same, like a fucking chump. Do these people realize how much of my life, my personal and public decisions, my views of my fellow man and my plans for the future, were predicated on this being actually true? Not a single person had ever once bothered to take me aside and whisper “Hey, we know this isn’t actually true, we’re just acting this way because it leads to better outcomes for society, on net, if we do. Obviously we make exceptions for the places where the literal truth is important. Welcome to the secret club, don’t tell the kids.”

These were the people who always had told me men and women are equal in all things, explicitly saying that anyone who actually really believed this was a deplorable right-wing troll. I could taste the betrayal in my mouth. It tasted of bile. How had this happened to me again?

A couple years prior I had lost a woman I dearly loved, as well as the associated friend group, when I had Not Gotten The Joke about a different belief and accidentally acted as if I believed something that everyone agreed to say was true was Actually True4. I didn’t understand what had happened back then. Now it was starting to make sense. I was too damn trusting and autistic to make a reliable ally in a world bereft of truth.

Scott’s own reaction to / improvement upon Graham’s hierarchy of disagreement (which I just noticed you commented on back in the day, so I guess this is more for others’ curiosity) is

Graham’s hierarchy is useful for its intended purpose, but it isn’t really a hierarchy of disagreements. It’s a hierarchy of types of response, within a disagreement. Sometimes things are refutations of other people’s points, but the points should never have been made at all, and refuting them doesn’t help. Sometimes it’s unclear how the argument even connects to the sorts of things that in principle could be proven or refuted.

If we were to classify disagreements themselves – talk about what people are doing when they’re even having an argument – I think it would look something like this:

Most people are either meta-debating – debating whether some parties in the debate are violating norms – or they’re just shaming, trying to push one side of the debate outside the bounds of respectability.

If you can get past that level, you end up discussing facts (blue column on the left) and/or philosophizing about how the argument has to fit together before one side is “right” or “wrong” (red column on the right). Either of these can be anywhere from throwing out a one-line claim and adding “Checkmate, atheists” at the end of it, to cooperating with the other person to try to figure out exactly what considerations are relevant and which sources best resolve them.

If you can get past that level, you run into really high-level disagreements about overall moral systems, or which goods are more valuable than others, or what “freedom” means, or stuff like that. These are basically unresolvable with anything less than a lifetime of philosophical work, but they usually allow mutual understanding and respect.

Seems like yours and Scott’s are complementary: I read you as suggesting how to improve one’s own argumentation techniques, while Scott is being more sociologically descriptive, mainly in explaining why online discourse so often degenerates into social shaming and meta-debate.

I unironically love Table 2.

A shower thought I once had, intuition-pumped by MIRI’s / Luke’s old post on turning philosophy to math to engineering, was that if metaethicists really were serious about resolving their disputes they should contract a software engineer (or something) to help implement on GitHub a metaethics version of Table 2, where rows would be moral dilemmas like the trolley problem and columns ethical theories, and then accept that real-world engineering solutions tend to be “dirty” and inelegant remixes plus kludgy optimisations to handle edge cases, but would clarify what the SOTA was and guide “metaethical innovation” much better, like a qualitative multi-criteria version of AI benchmarks.

I gave up on this shower thought for various reasons, including that I was obviously naive and hadn’t really engaged with the metaethical literature in any depth, but also because I ended up thinking that disagreements on doing good might run ~irreconcilably deep, plus noticing that Rethink Priorities had done the sophisticated v1 of a subset of what I had in mind and nobody really cared enough to change what they did. (In my more pessimistic moments I’d also invoke the diseased discipline accusation, but that may be unfair and outdated.)

Lee Billings’ book Five Billion Years of Solitude has the following poetic passage on deep time that’s stuck with me ever since I read it in Paul Gilster’s post:

Deep time is something that even geologists and their generalist peers, the earth and planetary scientists, can never fully grow accustomed to.

The sight of a fossilized form, perhaps the outline of a trilobite, a leaf, or a saurian footfall can still send a shiver through their bones, or excavate a trembling hollow in the chest that breath cannot fill. They can measure celestial motions and list Earth’s lithic annals, and they can map that arcane knowledge onto familiar scales, but the humblest do not pretend that minds summoned from and returned to dust in a century’s span can truly comprehend the solemn eons in their passage.

Instead, they must in a way learn to stand outside of time, to become momentarily eternal. Their world acquires dual, overlapping dimensions— one ephemeral and obvious, the other enduring and hidden in plain view. A planet becomes a vast machine, or an organism, pursuing some impenetrable purpose through its continental collisions and volcanic outpourings. A man becomes a protein-sheathed splash of ocean raised from rock to breathe the sky, an eater of sun whose atoms were forged on an anvil of stars.

Beholding the long evolutionary succession of Earthly empires that have come and gone, capped by a sliver of human existence that seems so easily shaved away, they perceive the breathtaking speed with which our species has stormed the world. Humanity’s ascent is a sudden explosion, kindled in some sapient spark of self-reflection, bursting forth from savannah and cave to blaze through the biosphere and scatter technological shrapnel across the planet, then the solar system, bound for parts unknown. From the giant leap of consciousness alongside some melting glacier, it proved only a small step to human footprints on the Moon.

The modern era, luminous and fleeting, flashes like lightning above the dark, abyssal eons of the abiding Earth. Immersed in a culture unaware of its own transience, students of geologic time see all this and wonder whether the human race will somehow abide, too.

(I still think it will.)

Your writeup makes me think you may be interested in Erik Hoel’s essay Enter the Supersensorium.

Nice reminiscence from Stephen Wolfram on his time with Richard Feynman:

Feynman loved doing physics. I think what he loved most was the process of it. Of calculating. Of figuring things out. It didn’t seem to matter to him so much if what came out was big and important. Or esoteric and weird. What mattered to him was the process of finding it. And he was often quite competitive about it.

Some scientists (myself probably included) are driven by the ambition to build grand intellectual edifices. I think Feynman — at least in the years I knew him — was much more driven by the pure pleasure of actually doing the science. He seemed to like best to spend his time figuring things out, and calculating. And he was a great calculator. All around perhaps the best human calculator there’s ever been.

Here’s a page from my files: quintessential Feynman. Calculating a Feynman diagram:

It’s kind of interesting to look at. His style was always very much the same. He always just used regular calculus and things. Essentially nineteenth-century mathematics. He never trusted much else. But wherever one could go with that, Feynman could go. Like no one else.

I always found it incredible. He would start with some problem, and fill up pages with calculations. And at the end of it, he would actually get the right answer! But he usually wasn’t satisfied with that. Once he’d gotten the answer, he’d go back and try to figure out why it was obvious. And often he’d come up with one of those classic Feynman straightforward-sounding explanations. And he’d never tell people about all the calculations behind it. Sometimes it was kind of a game for him: having people be flabbergasted by his seemingly instant physical intuition, not knowing that really it was based on some long, hard calculation he’d done.

Feynman and Wolfram had very different problem-solving styles:

Typically, Feynman would do some calculation. With me continually protesting that we should just go and use a computer. Eventually I’d do that. Then I’d get some results. And he’d get some results. And then we’d have an argument about whose intuition about the results was better.

The way he grappled with Wolfram’s rule 30 exemplified this (I’ve omitted a bunch of pictures, you can check them out in the article):

You know, I remember a time — it must have been the summer of 1985 — when I’d just discovered a thing called rule 30. That’s probably my own all-time favorite scientific discovery. And that’s what launched a lot of the whole new kind of science that I’ve spent 20 years building (and wrote about in my book A New Kind of Science). …

Well, Feynman and I were both visiting Boston, and we’d spent much of an afternoon talking about rule 30. About how it manages to go from that little black square at the top to make all this complicated stuff. And about what that means for physics and so on.

Well, we’d just been crawling around the floor — with help from some other people — trying to use meter rules to measure some feature of a giant printout of it. And Feynman took me aside, rather conspiratorially, and said, “Look, I just want to ask you one thing: how did you know rule 30 would do all this crazy stuff?” “You know me,” I said. “I didn’t. I just had a computer try all the possible rules. And I found it.” “Ah,” he said, “now I feel much better. I was worried you had some way to figure it out.”

Feynman and I talked a bunch more about rule 30. He really wanted to get an intuition for how it worked. He tried bashing it with all his usual tools. Like he tried to work out what the slope of the line between order and chaos is. And he calculated. Using all his usual calculus and so on. He and his son Carl even spent a bunch of time trying to crack rule 30 using a computer.

And one day he calls me and says, “OK, Wolfram, I can’t crack it. I think you’re on to something.” Which was very encouraging.

Scott’s The Colors Of Her Coat is the best writing I’ve read by him in a long while. Quoting this part in particular as a self-reminder and bulwark against the faux-sophisticated world-weariness I sometimes slip into:

Chesterton’s answer to the semantic apocalypse is to will yourself out of it. If you can’t enjoy My Neighbor Totoro after seeing too many Ghiblified photos, that’s a skill issue. Keep watching sunsets until each one becomes as beautiful as the first…

If you insist that anything too common, anything come by too cheaply, must be boring, then all the wonders of the Singularity cannot save you. You will grow weary of green wine and sick of crimson seas. But if you can bring yourself to really pay attention, to see old things for the first time, then you can combine the limitless variety of modernity with the awe of a peasant seeing an ultramarine mural—or the delight of a 2025er Ghiblifying photos for the first time.

How to see old things for the first time? I thought of the following passage by LoganStrohl describing a SIM card ejection tool:

I started studying “original seeing”, on purpose and by that name, in 2018. What stood out to me about my earliest exploratory experiments in original seeing is how alien the world is. …

I started my earliest experimentation with some brute-force phenomenology. I picked up an object, set it on the table in front of me, and progressively stripped away layers of perception as I observed it. It was one of these things:

I wrote, “It’s a SIM card ejection tool.”I wrote some things about its shape and color and so forth (it was round and metal, with a pointy bit on one end); and while I noted those perceptions, I tried to name some of the interpretations my mind seemed to be engaging in as I went.

As I identified the interpretations, I deliberately loosened my grip on them: “I notice that what I perceive as ‘shadows’ needn’t be places where the object blocks rays of light; the ‘object’ could be two-dimensional, drawn on a surface with the appropriate areas shaded around it.”

I noticed that I kept thinking in terms of what the object is for, so I loosened my grip on the utility of the object, mainly by naming many other possible uses. I imagined inserting the pointy part into soil to sow tiny snapdragon seeds, etching my name on a rock, and poking an air hole in the top of a plastic container so the liquid contents will pour out more smoothly. I’ve actually ended up keeping this SIM card tool on a keychain, not so I can eject SIM trays from phones, but because it’s a great stim; I can tap it like the tip of a pencil, but without leaving dots of graphite on my finger.

I loosened my grip on several preconceptions about how the object behaves, mainly by making and testing concrete predictions, some of which turned out to be wrong. For example, I expected it to taste sharp and “metallic”, but in fact I described the flavor of the surface as “calm, cool, perhaps lightly florid”.

By the time I’d had my fill of this proto-exercise, my relationship to the object had changed substantially. I wrote:

My perceptions that seem related to the object feel very distinct from whatever is out there impinging on my senses. … I was going to simply look at a SIM card tool, and now I want to wrap my soul around this little region of reality, a region that it feels disrespectful to call a ‘SIM card tool’. Why does it feel disrespectful? Because ‘SIM card tool’ is how I use it, and my mind is trained on the distance between how I relate to my perceptions of it, and what it is.

That last paragraph, and especially the use of ‘disrespectful’, strikes me a bit like the rationalist version of what Chesterton was talking about in Scott’s post.

Just signal-boosting the obvious references to the second: Sarah Constantin’s Humans Who Are Not Concentrating Are Not General Intelligences and Robin Hanson’s Better Babblers.

After eighteen years of being a professor, I’ve graded many student essays. And while I usually try to teach a deep structure of concepts, what the median student actually learns seems to mostly be a set of low order correlations. They know what words to use, which words tend to go together, which combinations tend to have positive associations, and so on. But if you ask an exam question where the deep structure answer differs from answer you’d guess looking at low order correlations, most students usually give the wrong answer.

Simple correlations also seem sufficient to capture most polite conversation talk, such as the weather is nice, how is your mother’s illness, and damn that other political party. Simple correlations are also most of what I see in inspirational TED talks, and when public intellectuals and talk show guests pontificate on topics they really don’t understand, such as quantum mechanics, consciousness, postmodernism, or the need always for more regulation everywhere. After all, media entertainers don’t need to understand deep structures any better than do their audiences.

Let me call styles of talking (or music, etc.) that rely mostly on low order correlations “babbling”. Babbling isn’t meaningless, but to ignorant audiences it often appears to be based on a deeper understanding than is actually the case. When done well, babbling can be entertaining, comforting, titillating, or exciting. It just isn’t usually a good place to learn deep insight.

It’s unclear to me how much economically-relevant activity is generated by low order correlation-type reasoning, or whatever the right generalisation of “babbling” is here.

This reminds me of Patrick McKenzie’s tweet thread: