Someone posted this photo recently. I can’t find a definitive original source, but multiple social media posts (Reddit, Twitter, Instagram), with different photos of the same object, all identify it as a 4,000-year-old wagon found in Lchashen, Armenia:

A few interesting things to note about the wheels:

First, contrary to popular belief, wooden wheels like this were generally not made from cross-sections of logs. Look at the grain: they were assembled from planks.

In The Wheel: Inventions and Reinventions, Richard Bulliet writes:

When three planks were used, they were fastened together by mortise and tenon—that is, tab A in slot B—and glue, and sometimes were reinforced by thin strips of wood going crosswise instead of radially.

(A Twitter commenter suggests that “Tree rounds unavoidably split radially when seasoning.”)

Second, look at how the hub is wider than the rest of the wheel. Why make it that way? Given the material (wood) and the level of precision attainable at the time in manufacturing, if the hub were narrower, the wheel would wobble too much on the axle:

If the round hole that the axle goes through in the center of the wheel is roomy enough for the wheel to turn without much friction, however, a narrow wheel will inevitably tilt to the side a bit and wobble when it rolls, eventually wearing through the axle.

Of course, you could just make the entire wheel that thickness, but then it would be too heavy. So: thin wheel with a thick hub.

Here’s an even older wheel. Notice anything different?

Look closely at the hub and the axle.

The hub is square. That’s because this wheel does not rotate on its axle: the axle and both wheels attached to it all rotate together, as a unit. This design is known as a “wheelset.”

A wheelset is easier to construct. The drawback is that it is harder to steer: On a turn, the outer wheel needs to rotate faster than the inner one. When they are both fixed to the same axle, this can’t happen, so at least one of the wheels drags on the ground. Wheelsets may have initially been used for mine carts that mostly followed short, straight tracks.

Independently rotating wheels are better for, say, an oxcart, which needs to turn in fields and on roads:

A wagon, which has four wheels (vs. two for a cart), has another steering problem: the wheels should ideally be angled on turns. This is typically achieved with a front axle that rotates:

Thousands of years later, when we get to the automobile, we have a new problem.

Carts and wagons steer via the animal in front: when the animal turns, it pulls the vehicle behind. With cars, for the first time, the steering needs to be initiated from inside the vehicle itself.

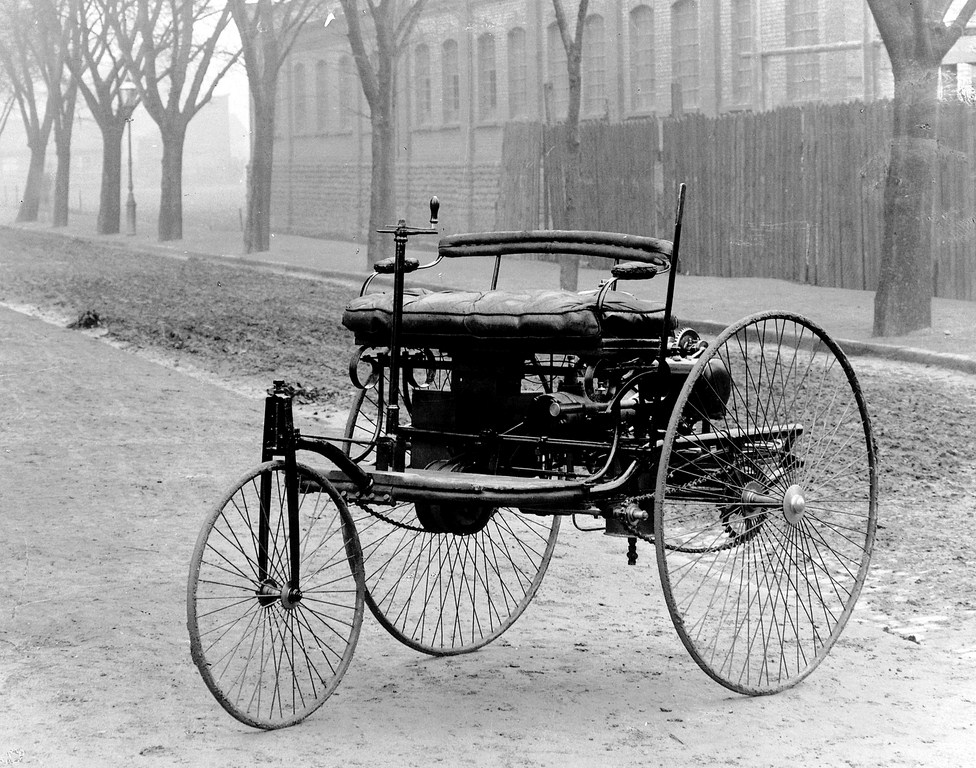

The first prototype automobiles dealt with this by only having three wheels:

They were driven by the two wheels in the back; the lone front wheel was used for steering, like a bicycle.

With a four-wheeled car, getting steering right is tricky. Ideally, you want the front wheels to angle, but at different angles, so that the axle lines of all four wheels converge at a single point, which is the center of the turning circle:

This is achieved through a brilliant linkage mechanism known as Ackerman steering (although it was actually invented by Georg Lankensberger):

So, the wheel has been reinvented multiple times—and that’s a good thing.

Source for most of this is The Wheel: Inventions and Reinventions, by Richard Bulliet.

Originally a Twitter thread.

Wheel reinvention is a very serious matter, which is why I want to make sure the people seeing this post get the best possible experience. Did anyone else see the images not load?

That’s how mine looks

Ugh, not sure what happened. Will fix

Fixed. Sorry and thanks for the heads-up!

Fascinating stuff, as always, Jason.

Have you seen Ted Cloak’s PDF about the cultural evolution of wheels? It’s a fascinating document. Before there was Dawkins, there was Cloak. His 1968 study (PDF) of the cultural evolution of the spoked wooden wheel and documentation of the manufacture of same (with photos) is a classic document, one not widely enough known. Here’s a website he’s put up setting out his ideas. Pay particular attention to his use of the work of William Powers (includes a number of useful videos of Power’s Model, perceptual control theory).

And then there’s this Note the following passage from David G. Hays, The Evolution of Technology, Chapter 5, “Politics, Cognition, and Personality”: “In reading to prepare to write this book, I have learned that the wheel was used for ritual over many years before it was put to use in war and, still later, work.”

Interesting, had not seen this, thanks Bill.

It’s rather obscure. I forget how I first bumped into, but I think it was an accident.

There’s no link for your mention of Ted Cloak’s website. Presumably this is it.

Yes, that’s it.

Thanks for the post and I think it’s probably a great example of very general processes/dynamics. While not something I could write I think it would be fascinating if someone were to identify X number of devices/concepts and then trace that history from first known instance to current. Or maybe even some initial innovation/invention/discover and how that evolved into a number of paths.

The wheel might be a good example of that wheel → gears, wheel’s reduction in friction to any number of easier moving parts or other movement/motion such a very low friction roller tables/ways in factories, slides on drawers....

Just the other day one of the people in the group I was hanging out with over the weekend (bunch of racers at the track) made a comment about how the old “if it’s not broke, don’t fix it” can be very problematic. I think that applies to pretty much all things and most ideas/knowledge. We need to always go back and reevaluate current state in the now newer context of what is known—we may well find it’s time to reinvent what seems to be working just fine. I suspect that is something that gets forced on us when some type of “disruption” event occurs that is either finding itself limited by current structures or the current X about to be case aside as the path forward takes a more radical turn but sufficient interests want to keep X relevant for as much longer as they can.

Side question—did any of the sources you looked at mention if different wood was used for making the wheel-hub (looks like that is one piece but maybe not—if not any differences there) and the axle the wheel was rotating on? Or even anything about lubrication attempts?

My main source for this is the one book by Bulliet, and he did not cover those topics that I recall.

But yes, friction is a major issue, and a significant part of the story is the history of bearings, including roller bearings and ball bearings.

Talking about re-inventing stuff, why did the people have to re-invent the concepts of factory lines and replaceable parts when the Venetian Arsenal had implemented these practices in the 1600s? Why’d we ever stop, given the sheer productivity of the place?

Sorry for going off topic.

This would depend on someone’s definition of ‘wheel’.

If it refers to literally just the round object then it would seem to be no.

If it refers to the entire mechanical system, then yes, innumerably.