A Primer on United States Treasuries

A few years into my career, I came to the realize that most investment markets, especially those most regular people invest in (equities), have strong relationships to the United States Treasury (UST) market.

Considering the recent moves in that market, I want to explain what the UST market is and how it relates to equities, loans and other investments.

A United States Treasury is a debt obligation backed by the full faith of the United States government. Anyone can buy a United States Treasury, but they are primarily purchased by institutional investors and governments. Today, USTs are considered the safest investments in the world.

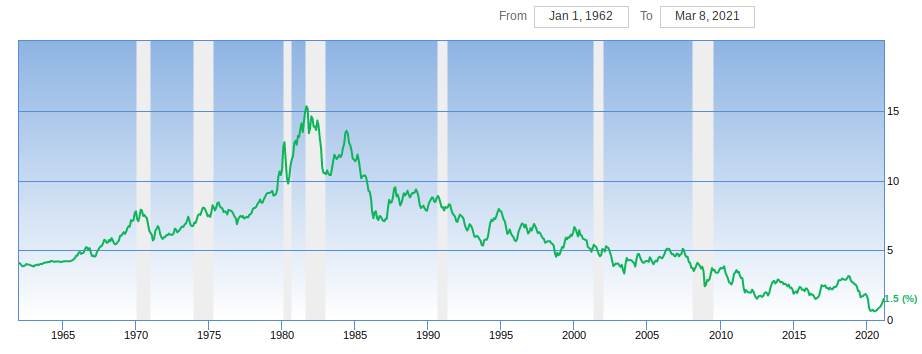

One of the most common UST is the UST 10 year bond. Today, an investment in the UST 10 year bond will yield you about 1.5% per year. This means that if you invest $1,000, you will get $10.50 a year until it matures in 2031 and you get your $1,000 back.

The historical 10 year yield. Source

You can buy treasuries that mature in most months and many different years, but only a select few are tracked by the markets, and are the reference rates that are used by the markets to drive expectations and investment decisions.

The most common UST rates tracked by market participants. Source

So how do other investment assets relate to USTs? It is important to note that the relationships I am about to explain are just one input in determining the price of the assets in question. These relationships do not always hold. Treasury rates affect not only the asset classes below, but many other asset classes and financial instruments such as commodities, futures, and options.

Foreign Exchange

All else being equal, when USTs are rising across the board, it means that the United States dollar will strengthen, assuming that rates in the foreign currency in question are stable or dropping. For example, if UST rates are rising, and Canadian Government Bond rates are falling, the US Dollar will get stronger versus the Canadian Dollar. This is simply because as rates rise, it becomes more attractive to purchase United States Treasuries. Therefore major market participants would find it appealing to sell their Canadian Government Bonds, sell Canadian Dollars for US Dollars and buy USTs.

Corporate Fixed Income Securities

The simplified version of obtaining the yield for a fixed income security is benchmark rate + credit spread. In the case of US dollar denominated corporate bonds, the benchmark rate is the UST that matures closest to the corporate bond. For example, a 5 year Wal-Mart bond would have a yield of 0.80% (5 year UST rate) + 0.50% (roughly the credit spread of the company) for a total of 1.30%. The relationship between yield and price works like this: when the yield rises, the price falls. So if the 5 year UST rate goes from 0.80% to 1%, all else being equal, the Wal-Mart 5 year bond yield would go from 1.30% to 1.50%, meaning the bond price would fall.

Fixed Rate Mortgages and other Fixed Rate Loans

The rates you get for a US Dollar denominated mortgage and other loans depend on the level of the benchmark UST at the time of loan issuance. Like a corporate fixed income security, the length of the loan determines the benchmark UST rate. The higher the UST rates, the more expensive your mortgage / loan will be.

Equities

The relationship between USTs and equities is quite complex, and there are a lot of factors that determine the strength of the relationship. At the risk of over-generalization, the general relationship between UST rates and equities is the following: As UST rates rise, equities fall. Why? Two main reasons:

The majority of corporations use the debt markets as a tool to run their businesses. As I mentioned in the section above, when UST rates rise, loans get more expensive. Expensive borrowing increases interest expense, reducing the bottom line for the company, making it less profitable.

One of the most common ways to value a company is The Discounted Cash Flow Model. One of the inputs of the model is the discount rate. The higher the UST rate, the higher the discount rate. The higher the discount rate, the lower the present value of the company according to the model.

Understanding how treasuries are priced, what the treasury yield curve is, and the factors that impact treasury yields go beyond the scope of this post. However given how important treasury rates are to other asset classes, I find it important to attempt to understand these complex relationships. I hope that you find this primer to be a decent start in understanding this market and how it impacts other asset classes.

This is not investment advice. For informational purposes only. At the time of publication, I invested in strategies involving USTs, corporate bonds, and equities.

There are several other key points relating to treasuries (and nominal rates in general) which haven’t made it into your article, but are probably more important than anything you’ve mentioned:

Correlation with the real economy

Inflation (aka nominal vs real rates aka UST vs TIPS)

Hedging properties of treasuries

There is a general thread running through this whole article whereby you are alternating between “Treasuries” and “Risk-free rates”. Given that treasuries are considered the risk-free rate, there’s a degree to which mixing these things up “doesn’t matter”. Contrary to this, I think it is important to distinguish between these things, especially when talking about how these things relate to other assets.

Roughly speaking, there are two ways in which the risk-free rate affects pricing of other securities:

As an arbitrage bound / discount rate for pricing things in the future

As an “alternative” in an investment portfolio

(I associate the first one more with RFR and the latter more with treasuries)

Most of your examples are in reference to RFR. (In fact, everything you wrote could be replaced with “everything is discounted using DCF and the discount factors come from Treasury prices” (which somewhat misses the point that treasuries are priced via DCF...))

FX

The key question here is “which fx rate moves”. (Ie Forward rate vs Spot rates). The forward rate for an FX pair is defined by an arbitrage bound. (Actually there is much more which could be said about this relating to cross-currency basis, but this is not the place for that). The forward exchange rate (how many EUR can I buy with 100 USD in a years time) is defined by an arbitrage. I can either buy my EUR today and put them in a EUR bank account, or I can put my USD in a USD bank account today and exchange them for EUR in a year. If EUR rates are −50bps and USD rates are 0bps, then I will have either current_exchange_rate * .995 in a years time or forward_exchange_rate * 1 in a years time. These two values must be equal (otherwise there’s an arbitrage), so the forward exchange rate is fully determined by the differential interest rate in the two countries.

Now if interest rates go up in the US, then dollars vs euros today needs to move OR dollars vs euros in a years time needs to move.

This is [mostly] an arbitrage relationship rather than anything to do with USTs as an asset class.

There is a level on which these things are more complicated. mostly driven by the action of large foreign investors who typically have a maturity mismatch between their bonds (often long bonds) and FX hedges (often 3m-1y rolling). This generally means that spot rates bear the brunt of the moves.

Corporate Bonds

What you’ve written is technically true. (Although you could re-write the whole paragraph replacing “corporate bonds” with “US treasuries” and convey as much information).

This is [kinda] an “alternative” example. If I’m choosing between lending my money to the US Government and Acme Corp, then I expect to earn a rate slightly higher than if I lend my $ to the government.

When thinking about corporate bonds (at least higher rated ones) the important bit is (as you say) the credit spread. The more interesting question is “how does the credit spread relate to interest rates”. In general, they are positively correlated, because as interest rates go up, their credit burden goes up, so their creditworthiness goes down (and vice versa). [There’s some complications in all of this but lets leave aside for now]

Fixed Rate Mortgages and other Fixed Rate Loans

US fixed rate mortgages are a messy product. To first order, what you’re saying is true, but only in the same sense as everything else. “Everything is discounted using DCF and the discount factors somehow come from treasuries”. (Which is pretty circular).

Equities

That chart is a chart-crime on so many levels.

This misses the woods for the trees. Why do we use DCF? Because of alternatives. If a company is offering me $100 in cashflow in a years time, how much should I be willing to pay for that? Well, a decent starting point is “how much can I buy that (future) $100 from the government for. So another way of saying the same thing is: “If the return on owning treasuries increases (ie bond prices down, rates up) then the return on owning equities should increase (since people can get the a better return elsewhere otherwise)”.

Relatedly, you might find Fight The Fed (Asness) interesting.

Commodities, Futures, Options

Pretty much all of these fall squarely in the “risk-free rate as arbitrage” camp. (At least to a first order approximation).

Some important nitpicks:

I’m not sure what you mean by “common” here. Some senses in which the 10y isn’t the “most common”:

Not the highest outstanding notionals

Not the weighted average maturity (or duration) of the whole stock

Not the highest volume traded (either by notional or duration (or as a derivative))

I’m guessing you mean something like “most commonly cited by the financial media”.

Err… what? I’m not even sure what you’re trying to say? Perhaps you mean something like: “A few benchmark points are observed more closely”, but generally people making investment decisions will just take the whole yield curve. Or perhaps you mean “The US only issues bonds at a certain subset of durations”? Not really clear to me.

This is a massive problem people have when talking about bonds. USTs are treasury bonds not treasury bond rates. When USTs are rising, rates are falling. Here you mean something like “When USTs sell-off / fall and US rates rise …”.

Thank you for your response!

I have made some changes to the original post regarding your nitpicks. I agree with them.

I also appreciate your in depth breakdown of all of my sections, I think the community here will appreciate your detail follow up / counters to my post.

I am trying to think of a way to edit my post so that it is more clear that I use USTs and risk free rate interchangeably.