Epistemic Status: exploratory. I am REALLY not an economist, I don’t even play one on TV.

[Edit: After some discussion in the comments I’ve updated that that GDP-to-gold, or GDP-to-oil, are bad proxy measures for economic growth. Further thoughts on this in Oops on Commodity Prices]

You can call it by a lot of names. You can call it crony capitalism, the mixed economy, or corporatism. Cost disease is an aspect of the problem, as are rent-seeking, regulatory capture, and oligopoly.

If Scrooge McDuck’s downtown Duckburg apartment rises in price, and Scrooge’s net worth rises equally, but nothing else changes, the distribution of purchasing power is now more unequal — fewer people can afford that apartment. But nobody is richer in terms of actual material wealth, not even Scrooge. Scrooge is only “richer” on paper. The total material wealth of Duckburg hasn’t gone up at all.

I’m concerned that something very like this is happening to developed countries in real life. When many goods become more expensive without materially improving, the result is increased wealth inequality without increased material abundance.

The original robber barons (Raubritter) were medieval German landowners who charged illegal private tolls to anyone who crossed their stretch of the Rhine. Essentially, they profited by restricting access to goods, holding trade hostage, rather than producing anything. The claim is that people in developed countries today are getting sucked dry by this kind of artificial access-restriction behavior. A clear-cut example is closed-access academic journals, which many scientists have begun to boycott; the value in a journal is produced by the scholars who author, edit, and referee papers, while the online journal’s only contribution is its ability to restrict access to those papers.

Scott Alexander said it right:

LOOK, REALLY OUR MAIN PROBLEM IS THAT ALL THE MOST IMPORTANT THINGS COST TEN TIMES AS MUCH AS THEY USED TO FOR NO REASON, PLUS THEY SEEM TO BE GOING DOWN IN QUALITY, AND NOBODY KNOWS WHY, AND WE’RE MOSTLY JUST DESPERATELY FLAILING AROUND LOOKING FOR SOLUTIONS HERE.

Except that it’s pretty easy to see why. We have a lot of trolls sitting under bridges charging tolls to people who want to cross. Modern Raubritter can easily maintain a hard-to-refute image that they’re providing value, and so make it hard for anyone to coordinate to avoid them. It’s genuinely risky to unilaterally skip college, refuse to publish in closed-access journals, or leave an expensive city with a booming economy. You know you’re being charged a ton for some stuff you don’t want or need, but it’s hard to tell where exactly the waste is; it’s dissipated and concealed and difficult to disentangle. As 19th century businessman John Wanamaker said, “Half the money I spend on advertising is wasted; the problem is, I don’t know which half.”

But, for now, let’s try to get a factual picture of what’s actually going on.

Stagnant Commodity-Denominated Growth

GDP is supposed to be adjusted for inflation, but the calculation of the inflation rate is pretty political and might be misleading. What happens if you instead denominate in commodities?

This is the Dow-to-gold ratio for the past 100 years; as you can see, there are three major contractions in the places you’d expect: one in the Great Depression, an even deeper one that began around 1972, and the most recent in the Great Recession that began in 2008.

You get a similar picture looking at the US GDP-to-gold ratio:

and the global GDP-to-gold ratio:

In 100 years we’re looking at something like an average of 1.4% growth in gold-denominated stocks or GDP; and gold-denominated GDP is comparable to where it was in the 1980’s.

But maybe that’s just gold. What about GDP denominated in other commodity prices? Here’s US GDP in terms of crude oil prices:

Once again, this shows US GDP never really recovering from the 2001 tech bust, and not being much higher than where it was in the 80’s.

Compared to the global price of corn, again, US GDP barely seems to have an upward trend since 1980; something like 1.5% growth.

Compared to a global commodities index, once again, GDP seems no higher than it was in the 90’s.

This should make us somewhat suspicious that “real” GDP growth is overestimating growth in material wealth.

Of course, since median income has grown slower than GDP, this means that median income relative to commodities has actually dropped in recent decades.

Stagnant Productivity

Labor productivity, in dollars per hour, has risen pretty steadily in advanced economies over the past half-century.

On the other hand, total factor productivity, the return on dollars of labor and capital, seems to have stagnated:

Total factor productivity is thought to include phenomena such as technological improvement, good institutions and governance, and culture. It’s been stagnating in other developed countries, not just the US:

A Brookings Institute report broke down US total factor productivity by sector, and concluded that the declining growth from 1987 to today was in services and construction, while manufacturing and other sectors continued to improve:

Services and construction, please note, pretty much match the “cost disease” sectors whose prices are rising faster than the rest of the economy can grow: education, housing, transportation, and especially healthcare. As services become more expensive, they’re also becoming less efficient.

Declining productivity means that we’re doing less with more. This is particularly true for innovation, where, for instance, we’re not getting much increase in crop yields despite huge increases in the number of agricultural researchers, and not getting much increase in lives saved despite increasing volume of medical research.

Monopoly and Declining Dynamism

The Herfindahl Index is a measure of market concentration, defined by the sum of the squares of the market shares of firms in an industry. (If a single firm held a monopoly it would be 1; if N firms each had equal shares, it would be 1/N.)

US industries have become more concentrated since the mid-1990s, with the number of firms dropping and the Herfindahl index rising:

Firms have also gotten larger:

You can also look at concentration in terms of employment. Education and healthcare are the most concentrated industries by occupation, while computers are the least:

There has been a steady increase in market power since 1980, with markups rising from 18% above cost in 1980 to 67% above cost in 2014.

More concentrated industries can charge higher prices relative to costs.

As industries are becoming more concentrated, they’re also becoming more static. Fewer new firms are being created:

Americans are moving less between states:

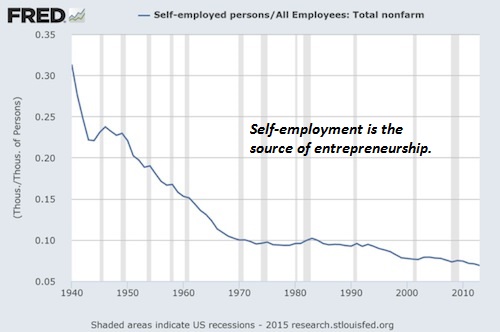

And self-employment is dropping:

As market power increases (i.e. as industries become more monopolistic), you can get a scenario where the financial value of firms outpaces their investment in capital or their spending on labor.

With an increase in market power, the share of income consisting of pure rents increases, while the labor and capital shares both decrease. Finally, the greater monopoly power of firms leads them to restrict output. In restricting their output, firms decrease their investment in productive capital, even in spite of low interest rates.

If you divide the economy into “capital” and “labor”, you find a long-term decline in the share of labor and increase in the share of capital. But if you decompose the capital share, you find that the returns on structures, land, and equipment are static or declining, while pure profits are on an upward trajectory:

This story is consistent with other long-term trends, like the increasing share of the value of firms that consists of intangibles — that is, “the value of things you couldn’t easily copy, like patents, customer goodwill, employee goodwill, regulator favoritism, and hard to see features of company methods and culture.

Those intangibles constitute barriers to entry, precisely because they can’t be easily copied by new firms. The rise of intangibles is also a sign of a more monopolistic economy.

It’s Not (Just) Regulation

Alex Tabarrok, a libertarian economist, argues that the decline in dynamism is not due to regulation.

Since the 1970’s, the most stringently regulated industry by far has been manufacturing:

(“FIRE” here refers to finance, insurance, and real estate.)

However, more stringently regulated industries are not less dynamic:

Some of these results are weird, since #622, marked as a lightly regulated industry, is “Hospitals”, which I don’t really think of as freewheeling. Maybe these numbers don’t include indirect effects like occupational licensing for medical professionals restricting the supply of people to work in hospitals.

But at any rate, regulations are not the only way to enforce monopoly power, and it seems that they’re not the decisive factor. Governments have means other than regulation to promote monopoly (for instance, grants, contracts, or subsidies to insider firms, or increases in the scope of what can be patented and for how long). And there are purely private mechanisms (like prestige/signaling in the scientific publishing industry) that can preserve monopolies as well.

Problems for the Middle and Lower Classes

US income inequality is rising; in real dollar terms, this looks like the rich getting richer while everyone else stays the same:

On the other hand, it’s worth moderating this picture by awareness of cost disease. High-income people as well as lower-income people are spending a larger fraction of their budget on housing and healthcare, which aren’t really improving much in quality.

Income mobility is also dropping:

Some Slogans

Why is monopoly bad?

Monopoly drives up prices while depressing production. That means we have fewer nice things. Yes, even for the “winners” of this negative-sum game, though of course the problem is worse for everyone else.

Monopoly and lack of innovation go together, since monopolists have less incentive to produce or compete.

Monopoly and intangibles go together. Branding is a form of market power. As are patents.

Monopoly causes inequality; it also causes absolute economic insecurity (if necessities cost more, the poor are most harmed).

Monopoly is anti-meritocratic. It’s a troll guarding a bridge, not a hardworking genius inventor.

None of this tells us what to do about monopoly. I’m not at all confident that antitrust law works or is a fair solution to the problem. There’s also reason to doubt that deregulation would fix everything, though fixing zoning and occupational licensing laws seems like it would at least help.

I’m curating this post as well as the corresponding Oops post.

Independently, this post does lot of good things I’d love to see more of on LessWrong – it looks at a complex problem, formulates a model of how to think about it, and then does some empiricism to see how the model bears out. The subsequent discussion of the post was great for fleshing out and correcting bits of the model.

I’d have curated this post regardless, listing some potential areas of improvement. But Sarah’s followup Oops post addressed almost all the concerns I had about it. The overall dynamic here was exactly what I’d like to see more of on LW:

Enough confidence to go form a model specific enough to be useful (and potentially wrong)

Discussion of that model, finding it’s weak points

Subsequent updating

The only thing I’d ideally like to see with things like this is more retroactive updating of the original post, so that people who find it afterwards get to see the full updated version. This is partly an issue of how LessWrong currently interfaces with common human psychologies, and we may try to update the site in the future so that going back to edit a post is more hedonic.

GDP-to-gold doesn’t really mean anything. If e.g. the average person wanted to hold 2% of their wealth in gold, and there is no way to get more gold, then (value of all assets) / (price of gold) is going to stay stable, regardless of how rich we are actually getting. The graph tells you something about the popularity of gold, and maybe the interest rate (which very directly affects (total wealth) / (GDP)), but nothing about growth.

I think GDP-to-oil also seems pretty silly, though less obviously so (gold is quite silly). As an analogy, if you measure GDP-to-land, you won’t see a long-run increase. That doesn’t mean that we aren’t getting richer—in fact it doesn’t tell you much of anything, because it’s basically what you’d observe in every possible world where you can’t increase the total supply of land. “Things we pull out of the ground” is a bit more elastic than the ground itself, but it’s still pretty inelastic.

The basket of commodities looks like it’s 75% fuel and metal, so I think the same basic criticism applies to that graph.

GDP-to-corn seems more real. The growth rate in your graph seems to be 1.7%/year. That’s compared to 2.7%/year if we use CPI. So there is a real gap there. This could be explained either by noise (the rate of corn-denominated GDP growth depends hugely on which years you pick, which lower bounds the noise, with some periods being smaller than CPI and some periods being larger). It could also be explained by pretty mundane stories like “technology improves productivity faster areas and slower in others; from 1985-2015 agriculture has been a low-tech area.”

It seems like it would be more useful to talk about why you object to CPI.

I agree it’s been a really bad 50 years, it’s been a very rare period of slowing growth, but I don’t think those data really show that. (And I think you are overstating how bad it is.)

Independently, I’m pretty unconvinced on monopoly as the explanation for the great stagnation. Most of your graphs on “how monopolistic are we” show pretty small or zero differences between now and the early 20th century. In general the effect seems too large to be naturally explained by increasing concentration, without some more convincing causal story.

Ok, this is a counterargument I want to make sure I understand.

Is the following a good representation of what you believe?

Yes. The detailed dynamics depend a lot on the particular commodity, and how elastic we expect demand to be; for example, over the long run I expect GDP/oil to go way up as we move to better substitutes, but over a short period where there aren’t good substitutes it could stay flat.

I appreciated the GDP-to-gold graph exactly because it’s not doing the thing the OP thinks it is doing, but rather showing the extent to which gold is a favored store of value slash the growth rate of wealth as opposed to income/production (GDP), and what that implies about the value of gold as an investment and the forward interest rate. It’s much cleaner than how I’d been thinking about it before, and the logic likely extends (amusing graph: GDP-to-Bitcoin, world is clearly ending).

Same with the hypothetical GDP-to-land, here, since that seems to have important implications worth thinking about, as well.

GDP-to-oil is going to have a lot of idiosyncratic movement as oil supply changes and our energy sources evolve.

GDP-to-corn is going to capture some idiosyncratic movement from agriculture, as Paul notes, and also for corn in particular—I’m guessing its subsidies make it a special case? So it’s kind of like we’re multiplying GDP-to-CPI by CPI-to-corn for some smart thing in the CPI slot, but the question of how much food our stuff is worth does seem like a good sanity check. How much food a worker can buy with their labor, better still.

Sure, but we don’t expect a long-term positive trend in GDP/gold. If it’s roughly constant over the long term, the conclusion is “people’s attitude towards gold isn’t changing too much,” not “we aren’t getting richer after all.”

Why is GDP-to-oil silly? It seems less like GDP-to-land and more like GDP in energy-backed currency. If I wanted to measure the output of an alien civilization, I’d use a measure like that.

I think GDP/(price of energy) is going up, as is total energy output.

ETA: in fact the price of electricity seems to be rising slower than inflation (residential and commercial electricity prices are falling by >0.5%/year here, industrial prices are flat), so your intuitive measure would suggest that CPI-adjusted GDP growth understates rather than overstates real growth.

I agree oil isn’t as bad as GDP-to-land, even if oil supply is perfectly inelastic, because there are better substitutes—if you get richer, you can replace oil with gas or with electric cars and so on. But it’s not too surprising to have a 30 year period where oil is significantly better than the next best alternative, and during that period the substitutes don’t take much pressure off the price and it’s almost as bad a measure as GDP-to-land.

I don’t understand, if everyone gets richer while the amount of gold stays fixed, wouldn’t we expect people to choose to hold a smaller proportion of their wealth in gold?

Why would they want to hold a smaller proportion of their wealth in gold?

(It’s not like I have a desire to hold a certain volume of gold, or a certain total amount of money in gold. I think most people view it as an investment, and I don’t see why the “fraction of your portfolio you want in gold” would change that much as gold becomes more valuable.)

I desire to physically posses a limited amount of gold coins, not as investment, but as hedge against the unlikely case where civilization collapses enough that more fictional assets (gummint scrip and electronic “investments”) are worthless but not so much that more traditional value stores are (widely realized to be) worthless.

Even if most people view it as an investment, presumably the price of gold is at least somewhat tied to how much people want it for non-investment purposes (otherwise you seem to be saying that its price is a pure Keynesian beauty contest). If you are richer, the non-investment value of gold seems to be less relative to your total resources (since gold is still just gold).

I don’t buy this, for a handful of reasons. Most important is the historical evidence of highly innovative ‘monopolies,’ like Carnegie Steel, Standard Oil, AT&T, and Microsoft.

Second are some basic models of innovation. Suppose it’s the case that innovations are easily transferrable, or come from outside vendors, and the user of the innovation is in a commodity market. (Suppose a new, more efficient loom is invented by the loom-making company, which sells to all cloth factories.) Then, the gains to innovation (the increased efficiency of this loom) are captured by a combination of the inventor (who gets to sell their new product) and the customer (who gets the reduction in commodity prices), with none of it going to the user (who has to lower their prices with the new efficiency, as their competitors are doing the same). What happens if the user of the innovation is a monopolist? Well, then they get to keep the profits (that don’t go to the inventor), as they can maintain prices while having lower costs.

[Note that this makes differing predictions for “customer fit” innovations and “increased profit” innovations. Under this model, a static monopolist is unlikely to experiment and find ways to satisfy customers better, whereas it is likely that they will find ways to increase prices and cut costs. The example of Prego chunky spaghetti sauce (popularized by Gladwell) is something that seems obviously brought on by competition between firms, as opposed to basic research funded by monopoly profits.]

Further, consider innovations that have some variable benefit (like a decreased cost for every unit made) but a fixed cost to create (perhaps the cost of experimentally determining the optimal amount of solder to use on a barrel costs the same regardless of how many barrels you make). Then the larger the firm, the more likely such an experiment is to be run—a small firm will find many such experiments not worth their time, whereas Standard Oil will think they are.

---

A story I often tell about the modern economy is that returns to intelligence are increasing, and this more and more pushes industries into a winner-take-all dynamic. (Increasing returns to any variable factor will increase inequality in a domain, so long as it’s not sufficiently negatively correlated with previous inequality.) If it’s the case that having a data science team makes a company cumulatively more efficient at what it does, and there’s a meaningful difference between a first rank and second rank data scientist, and data scientists want to work with top data scientists, then you end up with the industry leader able to attract the best data scientists (because they’re the most fun company to work at), and pay them less (it’s fairly standard for the #2 firm to actually have to pay more than the #1 firm, because at equal prices people would just go to the #1 firm), and use them most effectively (since their larger scale means they have more data, and will find smaller opportunities more worthwhile in absolute terms). And so, unsurprisingly, more and more of the profits in an industry go to the top firm, and smaller firms find it more and more difficult to survive (as their scale might not justify hiring even a single data scientist, and the ones available for them to hire aren’t great).

That said, most of my attention is on the manufacturing sector. (It’s where many of my historical examples came from, was a fairly large part of my education, and most of my experience in private industry.) I am pretty convinced of the ‘troll under the bridge’ story for rising costs and decreasing quality elsewhere. It doesn’t seem like Harvard is innovating in education technology anywhere near how Intel in innovating in semiconductor manufacturing technology (if Harvard is innovating at all!).

But this says to me that firm size / degree of competitor isn’t the core factor. Something closer to ‘style of competition’ seems much more right. The Raubritter is empowered by facts of geography forcing you to pass by him, whereas Carnegie Steel is just making higher quality products more cheaply and quickly. If you could teleport a modern steel company back in time, they could put Carnegie out of business; teleporting a (civilian) cargo ship back in time (or even a modern road) doesn’t put the Raubritter out of business.

I don’t know about Carnegie Steel and Standard Oil, but calling AT&T and Microsoft “innovative monopolies” is a bit of a misnomer in my book. These companies were innovative. Their innovation allowed them to become monopolies. After they reached their monopoly position, they largely stopped innovating, outside of making incremental improvements to their core products.

In the case of AT&T, once it had its monopoly position, what innovations did it bring to the consumer? Sure, the transistor was invented at Bell Labs, but it was actually commercialized by Shockley Semiconductor, and later by Fairchild Semiconductor. Likewise, Bell Labs also invented Unix, but it was actually commercialized by companies like SCO, HP, Sun, and SGI.

Microsoft, in turn, made significant strides in consumer desktop operating systems, but once it had its monopoly, it stagnated. Sure, MSR came up with innovation after innovation, from practical microkernels to a predecessor to the iPad, but were those innovations ever brought to market? No. They were dismissed as research projects and were written off as the cost of finding “real” innovations that would incrementally improve the core desktop/server business. Meanwhile, Microsoft worked hard to use its dominant monopoly and patent positions to suppress competition from other operating systems and alternate modes of computing.

It seems to me that in practical terms, there is no such thing as an “innovative monopoly”. Once a company reaches a monopoly position, its incentive structure is to suppress all innovation that does not improve its core business. It has moved from an “explore” model to an “exploit” model. When that exploitation is threatened, it uses regulatory means to position itself as a “gatekeeper” or “troll” (as Sarah Constantin puts it) to extract a tax in order to make competition either completely unviable or get enough incremental revenue to fund its own efforts to compete with the new entrant.

Is that actually true? Or would Carnegie be able to use his monopoly position to simultaneously undercut the modern steel company’s prices, while using his influence with other sectors of the economy to drive up input costs, using his influence with government regulators to increase the regulatory burdens that would have to be borne by the smaller competitor, and simultaneously working to reverse-engineer the proprietary secrets of his new competitor? Either that, or (like Facebook, Google, or Apple today) he’d just straight up buy his competition, and either incorporate its innovations into his products (if they were compatible) or just suppress them (if they were incompatible). Or if he weren’t able to eat the company wholesale, he’d poach the talent, much as Google, Facebook, and Uber poach AI talent from research labs.

It’s not at all clear to me that a modern steel corporation, teleported back in time, and placed in a competitive position to Andrew Carnegie would be able to actually successfully compete with Carnegie without government intervention.

So given all this, why are there new firms at all? Why was Microsoft able to topple IBM? Why were Google and Apple able to topple Microsoft?

I think the answer lies in the original firm not knowing fully who its competitors are. IBM thought of itself as a hardware manufacturer, and specifically a mainframe hardware manufacturer. Microsoft was a PC software manufacturer. The two categories were worlds apart from IBM’s perspective.

It’s executives could not perceive the PC as a threat. Rather, they saw the PC as colonizing a new market, a market that IBM’s core business had no real interest in. Then, by the time that IBM realized that the vast PC market was going to limit demand for mainframes, it was too late. Microsoft had already established a dominant position among personal computers and it would have been cost prohibitive for IBM to compete. In fact, IBM recognized this, and attempted to “cooperate” with Microsoft on a new operating system. However, Microsoft was able to see the effort for what it was and block IBM’s attempt to regain control of the desktop PC market.

Microsoft, similarly, initially dismissed the iPhone as a joke. It did not see that the future of computing was in mobile devices, not desktop and laptop machines running Windows. Just like IBM, it focused on its core businesses of operating systems and productivity suites, and only realized too late that the core business had been walled in by the much larger mobile computing market. And again, just like IBM, by the time it realized this, it was far too late for it to establish a beachhead and compete, even though it tried repeatedly.

In the same way, Xerox actually invented most of the technologies that led to its demise. The personal workstation, the GUI, the mouse, and many other innovations were all invented at PARC. However, Xerox executives never imagined these innovations displacing the copier, so they felt free in dismissing them as pie-in-the-sky toys to keep the researchers happy.

Google, Facebook, and Apple, so far, have not made these same mistakes. Facebook, especially, has been aggressive about acquiring competitors that could build alternate social graphs, even if their functionality is radically different than Facebook’s. Likewise, Google has recognized that its core business is to funnel ads to viewers, and has not been shy about acquiring other firms whose business model threatens Google’s ability to do so. Whether this aggressiveness will last depends on a whole host of contingent factors, like executive competence, regulatory oversight and short-term market pressures on the core business. In the near term, however, the new tech monopolies do appear to be qualitatively more paranoid in a way their predecessors were not.

I don’t think that’s fair. Microsoft did have a mobile OS before Apple. It’s just that they didn’t get the idea that very simply UI is better than a UI that’s accessed via a stylus along with a hardware keyboard. I think they also didn’t have the haptic feedback that you do get on iOS and Android when software buttons are pressed. It’s quite interesting that you can give user that clicks software button haptic feedback without them being aware that the phone in their hand vibrates when they press a button. There were a bunch of interesting ideas that were needed to get the concept to work.

Microsoft could have invented those, instead of Apple, if Microsoft invested the resources into mobile devices that Apple had. Instead, Microsoft treated the entire mobile device space as a sideshow, or an adjunct to desktop computing.

Meanwhile Apple, perhaps because of its success with the iPod, invested heavily in mobile device hardware engineering, mobile UI research, building relations with suppliers, and all the other necessary things to not just invent the iPhone, but manufacture it and sell it by the millions.

AT&T did not sell new products because it was banned from doing so from 1956, and probably effectively from earlier. But, as Vaniver says, it kept pursuing computers because it had a huge internal use for them, to make its telephone system cheaper to run, such as to replace the 300k switchboard operators.

Do you have a source for that? My understanding was that AT&T was the one doing the banning, by preventing consumers from connecting unapproved telephones (and other telecommunications equipment) to its lines.

That’s also true, but why would that have any effect on your belief about whether the government banned AT&T from selling unrelated products?

I was just quoting wikipedia, but googling “at&t 1956” brings up this:

or, if you don’t like pdfs, how about the wsj:

Most innovations are incremental improvements to core products. Yes, historical firms have rarely made use of revolutionary basic innovations, even if they invented them, but this seems to primarily have to do with institutional inertia.

Carnegie’s edge over his competition was something like five or ten years; a modern firm would be about one hundred years of research into metallurgy, tool generation, and industrial organization ahead. I agree that it’s more likely that they’d attempt to consolidate, and that industrial espionage would be a risk, but overall it seems pretty easy to call.

But how much of that innovation would it be able to actually use? How are you going to use processes that rely in high-precision components when you don’t have CNC machines to manufacture them? How are you going to check for defects with ultrasound when ultrasound machines are 50 years in the future? How are you going to use processes that rely on electricity when the power generation capacity to actually run those processes doesn’t exist yet? How are you going to use your newfangled industrial organization systems when your workforce hasn’t mentally incorporated many of the social norms needed for an industrialized society? How do your engineers even communicate with e.g. machinists, when there’s been a hundred years of notational changes?

I have a great story from the petrochemical industry on this very topic. A firm is trying to optimize one of its chemical plants, built a mere thirty years ago. In theory this should be an easy job. The firm looks up its own documentation on the plant, plans the improvements, and executes them. In practice:

Transporting a modern steel mill a hundred years into the past would easily an order of magnitude more difficult than this, and I can see the difficulties therein easily wiping out the potential efficiency gains.

When I said “company,” I was also including the employees, as potentially more valuable than the physical plant. Including the supply chain also is probably unfair, but I expect they could get pretty far with converting on-hand present-day cash to supplies before being teleported back in time.

This seems possible to me; even if they have to abandon lots of tools as unsupported by their new supply chain, I imagine them getting a lot out of a hundred years of scientific development.

I was also including the employees of the company itself, and all the machinery and equipment that the company has on hand. However, today, we live in a world of just-in-time supply chains, with companies subcontracting various specialized functions out to various subcontractors. Very few companies are the sort of vertically integrated enterprises that Ford or US Steel were at the turn of the century. As a result, a lot of the knowledge that you’re attributing to the individual company is actually in the supply chain for the company, not the company itself. This applies not just to the nitty-gritty of actually building components, but even matters of overall product design. As an example, Foxconn has a large say in iPhone manufacturing, because, at the end of the day, they’re the ones putting the things together. In the auto industry, parts suppliers like Mopar or Denso often know more about the cars that Chrysler and Toyota build than Toyota or Chrysler themselves.

In addition, companies today carry much less inventory than they used to, as a result of the aforementioned JIT supply chains. So even if your modern steel corporation could be operated with 1899-era machinery and infrastructure, it’s still might not do you any good, because you’d rapidly run out of iron, coke, and the special alloying agents needed to make modern high-strength steel. Today, you can rely on computerized inventory management and logistical planning systems that are deeply integrated with your suppliers to ensure that new supplies of raw materials and spare parts reach your production facilities right when they’re needed. How are you going to do that in 1899? Hire a bunch of telegraph clerks?

Moreover, this reliance on supply chains forms another pressure point that a monopolist like Carnegie could use to suppress your firm. He could work with the railroads (which were not operating under the common carrier regulations that they operate under today) to ensure that your factories were starved of raw materials, while his factories were well supplied. No amount of scientific expertise can conjure finished steel out of thin air.

Finally, you allude to cash reserves, but even that might be a problem. Not all corporations are as cash rich as Apple or Microsoft. And even Apple and Microsoft keep large amounts of their “cash” in various short-term investments, offshore holding companies, and various tax shelters. It’s not like Apple has a giant underground vault filled with hundred dollar bills in Cupertino. So if you transported a company back in time, it might not have enough cash on hand to make payroll, much less sustain ongoing operations.

I think many people strongly underestimate how interconnected and interdependent firms in the modern economy are. Many people have an idea of how firms operate that was beginning to be obsolete in the ’80s, and is wholly obsolete today. Firms are increasingly disaggregated, as computerization has reduced transaction costs, allowing for a more Coasean equilibrium.

That said, many of these innovations have only really taken root since 1980 or so. Prior to that firms were more like the sort of vertically integrated enterprises that people envision when they think of a classic industrial corporation. Perhaps US Steel from 1968 could go back in time and compete effectively with the 1899 version of itself. But I’m not sure that the US Steel from 2018 could do the same.

Once an actor reaches uncontested dominance, its incentive structure is to suppress all change that does not improve its position.

In my more paranoid moments, I suspect there’s something like this going on in general: American power actors want stagnation and fear change, because change can be destabilizing and they’re what would be destabilized. This is obviously true in the case of cultural power, but I’m not sure how it would extend beyond that.

I agree that Carnegie’s US Steel is not the type of “monopoly” that I consider socially harmful. I seem to remember that there is empirical evidence (though I don’t know where) that monopolies due to superior product quality/price are actually fragile, and long-term monopolies must be maintained by legal privileges to survive. (If anybody remembers where, I’d appreciate a reference.)

Leaving aside Carnegie Steel, would you consider either AT&T or Microsoft to be socially beneficial monopolies?

Why wouldn’t the loom company keep all the profits, by selling a loom bundle of the same production as before at the same price?

If the cost to the fabric factory is the same under both methods, then why bother switching? So it has to be cheaper by enough that it’s worth the effort to switch, at which point the profits are being split.

A possibly major thing that’s changed, which is worth looking into: in today’s world large firms often buy out smaller firms that they were competing with, and similarly-sized large firms often merge together. If the problem turns out to have a single root cause (which it might not), this seems likely to be it.

We have a regulatory regime where mergers and purchases are sometimes blocked, if a regulator thinks this would bring the amount of competition in some sector below a critical threshold, but in practice that threshold is only around 3 firms. While it’s illegal for firms to directly coordinate on high prices, if a combination of intrinsic barriers to entry and mergers gets the number of firms low enough, they can keep prices high using a tit-for-tat strategy which bypasses the ban on explicit price fixing. We also have a lot more firms spread between multiple industries, which enables a previously impossible strategy: maintaining high margins while credibly committing to cut margins if a new firm enters the market.

This paper by Steve Schmitz seems broadly relevant:

Note that the examples in the essay of mechanisms that produce inefficiency are union work rules, non-compete agreements between firms, tariffs, and occupational licensing laws. The former three are not federal regulations on industries, and so would not show up in a comparison of industry dynamism vs. regulatory stringency.

The vast majority of occupational licensing laws in the US are not federal regulation either.

Yeah, the gap between companies’ marginal return on cash investment and sector-specific [EDITED TO SAY: stock market performance] would be a better metric. This would still be incomplete; it leaves out factors like:

“Hollywood accounting” (systematic underassessment of profits in order to extract more money from counterparties with compensation tied to profits)

Labor’s share of income also being elevated by e.g. union work rules

Overall it seems like summary statistics are a pretty limited tool here relative to engaging with the concrete details of what’s going on in specific situations. (This is why I love Jane Jacobs so much.)

Can you explain why return on cash vs. return on equity matters?

Oops, I used the wrong term. I meant return on marginal investment vs returns on equities as an investment vehicle (i.e. stock market returns). Will edit to clarify.

The book The Fine Print covers a lot of examples of “special privileges granted by the government” in a number of industries (rail, telecom, energy). I read it a long time ago, so don’t remember a ton from it. But in case anyone’s interested in more concrete examples of this.

I very much appreciated this disclaimer, which reminds me of the Who the hell is Jeff?!? incident.

My sense is that moving houses incurs a cost proportional to the value of the house, if only because real estate agents typically charge a percentage fee instead of a flat fee. That seems tied to decreased migration, to me; it’s already well-studied that increased frictional costs to buying and selling a home in California from prop 13 leads to decreased migration.

It seems likely that this extends to the economy at large: as local knowledge and reputation (and other ‘intangibles’) become more important, the costs to moving increase. Yelp reviews tied to a particular location presumably make it more difficult to move a restaurant than it was 30 years ago, even as internet search makes it more possible for new businesses to be discovered. It seems likely that it was historically much easier to sell companies without retaining core staff, as the primary value of the company was in capital it owned; compare to a company now whose primary value is in intangibles or the human capital of particular employees.

The other story in decreased interstate migration is increased intercountry migration; wage differences between states drive movements between those states, but someone entering the country from outside is much more indifferent between states than someone who already has a home and job and social connections in a particular state. Sufficient migration to prevent those wage differences from getting high enough to overcome the energetic barrier of switching costs means fewer people move. But this isn’t obviously bad, and I bring it up mostly as part of a “what’s up with decreased migration, as a component of decreased dynamism?”

My experience moving is that the annoyance cost of moving—prioritization, search, negotiation, moving and changing your stuff, relearning your surroundings, making new friends, dealing with the kids, and so forth—towers over things like real estate commissions, even if you own a relatively expensive house, especially now that the internet is (finally!) driving them down. When recently considering a move, at first I thought the round-trip commission cost was an issue until I realized it was missing a zero versus other concerns.

In the UK, there is a tax payable any time you buy a house, called “stamp duty land tax”. E.g., if you buy a house costing £500,000 then you get taxed £15,000. This is a lot bigger than typical agents’ fees. But this may be a UK idiosyncrasy without parallels anywhere else—I’m pretty sure there’s no such thing in the US, for instance.

Prop 13 in California has vaguely similar consequences—property taxes are paid annually as a percentage of the assessed value of the property, but Prop 13 limits the assessed value of the property to grow by 2% per year at most, unless the property is sold, at which point the assessed value becomes the sale price. (The annual increase in median home price over that period has been closer to 8%.) Implicitly, this is a tax on selling homes that becomes larger the longer the house has been owned by a single party.

It seems to me that the core problem is about measuring value creation.

The field of education has a problem because the quality of the education between different institutions isn’t obvious to customers and as a result the institutions compete on prestige instead of competing on the quality of their work.

On the other hand when Intel produces microprocessors measuring the quality is really easy and there’s no way for Intel to compete on brand if they wouldn’t be able to better microprocessors as time goes on.

Occupational licensing is also about measurement. It’s usually a bad way to distinguish the quality between professionals. For many professions such as medicine I think that you could get good quality measurement by letting the professionals predict the outcomes of their interventions beforehand hand then provide the customers information about how well the professional is calibrated on predicting the effects of their interventions.

When it comes to construction I’m curious whether it’s a problem of the West or whether the problem also exists in similar way in China. Do the Chinese manage to increase productivity in construction?

Some images seem to have gone missing from the “It’s Not (Just) Regulation” section?

The images are from here, I believe figures 3 and 7, archived here.

Thanks!

Gonna take a while to digest, but the intro shows a common mistake.

This confuses”nominal” or “projected” price with an actual price, which is only known at time of sale. And you seem to believe that paper wealth (which may or may not EVER be converted into goods and services) is the same as purchasing power.

You’re correct that the total material wealth of Duckburg hasn’t gone up. Scrooge’s material wealth _ALSO_ hasn’t gone up, just his nominal wealth. And no other member of the city has been harmed or lost material wealth. The entire scenario of “price went up but literally nothing changed owners” is an accounting fiction with no direct impact on anyone.

So when you say

That’s not the same thing—those are REAL prices, which people have actually paid. And even if you factor out monetary effects by looking at what people pay in terms of hours of labor or the like, real prices for many things have gone up. For many others, of course, they’ve gone WAY down while quality improves. The median American worker can buy a pocket computer for less than a week’s labor which is literally thousands of times more powerful than they’d have gotten 30 years ago for over a month’s work.

That said, I agree with many of your concerns that there are more gatekeepers than producers, and many things cost too much, because many people are capturing parts of the money/product flow without actually providing value themselves. I’m not sure that “monopoly” is the right proxy to think about this problem, but it’s clearly a problem.

This seems like a mere technicality. Since Mr. McDuck can use the projected price as collateral for a loan, it gives him purchasing power without the need to actually sell anything. And for people who don’t own an apartment, increases in nominal price have a major economic impact: they pay more rent.

It’s standard practice in economic analysis to exclude the electronics sector, because it’s so unrepresentative of the economy as a whole. If you have an example that isn’t electronics or something closely linked to electronics, it’s worth bringing into the conversation.

If you use a house as a collateral, there is a probability you will lose your house, if I am not confused about collaterals. As such, someone accepting your house as a collateral is almost the same as them playing a lottery where with some percent chance they are forced to buy your house. So I think we should consider that transaction to be in the same category as selling the house.

It’s worth noting that projected prices play a significant role in decision-making, since decision-making is all about evaluating counterfactuals. Suppose Scrooge ties his purchasing decisions to his paper net worth; then his effective purchasing power changes even though he isn’t getting an income stream directly from the apartment. (Cases where he takes out a loan on the apartment, as jimrandomh suggests, do seem somewhat different.) That is, if his home is increasing in value, that means he doesn’t need to convert other income streams into savings as much, and so can convert them into consumption instead. Or he might make riskier financial decisions with other asset classes, trusting that the more valuable house could better offset losses elsewhere.

Edit: Epistomological status: armchair reasoning

You could take a loan with your house as collateral if you are more certain than your loan-giver that you will not default. If a bank tries to give people loans based on the probability they determine that you default, some of the population will happen to know their probability of defaulting to be underestimated, and take a loan at a profit. The bank would rather have their “fraudulent customers” be the ones that pay back loans more often than expected.

No, the whole point of using a house as collateral is that the bank only loses money if you default and the asset depreciates by more than the (loan size/house value) ratio.

I don’t think it’s fair to assume that Sarah is confusing nominal with actual prices. Unless you are using specialist terminology I’m unfamiliar with, she probably is using “projected” prices, but I don’t see what makes you think she’s confusing them with anything else.

Specifically, I take her references to the “price” of Scrooge’s apartment to mean something like “the price someone would actually pay if they bought the thing now”. Obviously this is a somewhat nebulous notion, and in particular there’s probably no good way to measure it reliably without substantial risk of changing the very thing you’re trying to measure. But it still seems a reasonable thing to think about.

And, with that notion of price, it’s not true that

if the price increases—because wealth is a matter of what you can afford to buy, and everyone else in Duckburg just became less able to afford apartments.

Cities generate wealth from the Economies of agglomeration. Bigger cities have higher productivity than smaller cities. Some of that wealth naturally flows into the land price. Here is a good introduction: Scale Economies and Agglomeration

People become actually richer in terms of natural wealth in cities. The source of wealth is not the property and land itself, but the utility value of the land has in producing the positive agglomeration effects. Land is one of the primary ‘factors of production’ (land, labor, capital). Just like farmland, urban land creates value from produced output happening on it. The soil itself has no value without cultivation. Urban land happens to be more productive than farmland and it becomes more valuable.

The solution to this problem is better urban planning. Inefficient land usage is bottleneck for growth in the cities and it should be treated as scare resource and used very efficiently. Just building more, building dense and have good infrastructure helps to reduce the cost of living in high productivity areas.

Hundreds of economists study this topic. Why not just read some books or papers?

I think part of the problem is that corporations are the main source of innovation and they have incentives to insert themselves into the things they invent so that they can be trolls and sustain their business.

Compare email and facebook messenger for two different types of invention, with different abilities to extract tolls. However if you can’t extract a toll, it is unlikely you can create a business around innovation in an area.

Really glad you wrote this post. I think it’s trying to speak to something I’ve been concerned with for a while—a thing that feels (to me) like a crux for a lot of current social movements and social ills in the States (including the social justice movement, black lives matter, growing homelessness / decreasing standards of living for the poorest people). And of course, the whole shit-pile that is our health care system.

Some Questions / Further Comments:

(Please respond to each point as a separate thread, so that threads are segregated by topic / question.)

1) My guess is that under “Services and construction”, where you list “transportation”, you mean a different “transportation” than the one in the graph, which has “Transportation and Warehousing” as its own category? I’d appreciate clarification / disambiguation in the article.

2) I agree with your point RE: intangibles, that they correlate / go together with monopoly. But it’s difficult for me to tell HOW MUCH they ‘go together’. And whether it is strictly ‘a bad sign’. While I’m not a huge fan of how patents sometimes play out, I am a fan of branding. While you can’t just try to transfer the effect of Coca-Cola’s branding to your new product, I think you can, in fact, try to compete on branding.

(It would be terrible if someone tried to take exclusive rights over the use of the color red in logos or something, though. Hopefully that doesn’t ever happen.)

And, honestly, I think the ‘value’ of their branding might not be too inaccurately priced, in some sense? (Even if the product reduces in quality, I think the branding has value beyond trying to measure quality of product.) I also don’t whether ‘intangibles’ includes things like ‘excellent customer service’, but if it does, that seems like true value, not ‘fake value’. Even though it doesn’t directly cash out into more product.

Over time, I think more of what we consider valuable should be in intangibles? Seems like a sign of people having enough useful things that they can now afford to put money into “nice experiences.” And in many ways, people value having fewer choices because it cashes out into less effort.

3) Similarly, ‘company culture’—while it is ‘dark matter’ as Robin Hanson says—seems appropriate to value highly in some cases. I don’t think most ‘monopoly situations’ are a result of some company just having a really good, un-copyable company culture, but in general, I do expect it to be very difficult to transfer / copy really excellent company cultures. And as a result, I do expect something monopolistic-looking to emerge as a result of—not shady dealings or exclusive privileges facilitated by government—but as a natural consequence of very few companies, in fact, being really good places to work.

I would really like to be able to disambiguate between the situations where: There are only 3 main firms in this industry. Is it because those 3 firms are in fact providing outsized value in a way that’s hard to compete with? Or, is this happening because the government made some poor decisions that favored certain companies for not-very-good reasons, and they leveraged this into an effective monopoly?

La Croix did this. It’s just flavored seltzer, the same as the 59c store-brand bottles, but it became wildly successful. What’s more, it had been around for a while before becoming successful.

What did they do?

I don’t think that’s the whole story. La Croix was originally positioned as an alternative to Perrier, whereas now (maybe as a result of the packaging in cans) it’s positioned as an alternative to soda. And the copy on the box is pretty distinctive—“calorie-free”, “innocent” and so on. (It isn’t quite grammatical, but that must be intentional. Trying to affect a European accent?)

There’s a plausible narrative where La Croix succeeded because no one else had tried packaging seltzer in cans, but there’s also a plausible narrative where it succeeded mostly because of its unusual branding.

If pressed, I’d favor the first—Poland Spring also has a line of expensive brand-name flavored seltzers, but the bottles are a little unwieldy, not the sort of thing you’d pack with a work lunch. But I’m not in the target audience for its branding, so.

The Elephant in the Brain has some relevant points—for some important industries such as medicine and schooling, consumers don’t prefer low prices.

Just to clarify, is the scenario that A) Scrooge owns the apartment building and the value of it has gone up (thus increasing his net worth), or is it that B) he rents the apartment from some other landlord, and coincidentally both his net worth and (the NPV of) his rent have gone up by the same amount?

Edit: on second reading, I’m pretty sure you mean A.

Speaking to the problem of financial wealth outpacing capital investment, I wonder about asset inflation due to open market operations for monetary policy. As I understand it, expanding the money supply works about like this:

The Federal Reserve adds assets to the reserve accounts of commercial banks.

These banks nominally have more money to loan, but there is no requirement that they actually issue loans with it, so they invest it in whatever is most profitable. Usually that is financial assets.

This process continues until the target inflation goal is reached.

The part about this that doesn’t make sense to me is that inflation is tracked based on the price of a basket of consumer goods. In particular, the Consumer Price Index. You can view exactly what goes into CPI by clicking ‘Show Table’ under the chart. The thing is, almost all of the money spent on financial assets stays in financial assets; the only amount that gets spent on the items in the CPI list is whatever portion is taken in fees for each transaction down the road.

If we assume that all the money that goes to fees gets spent on CPI goods, then if the fees amount to 5%, it looks like the central bank is adding 20x the amount of money needed to move the needle where they want it. The rest of that money is driving up the price of financial assets.

I’d be really happy to be wrong about this.

Yup, that’s not how it works :)

I don’t know exactly what you think “financial assets” are. Usually they are loans, so it’s more or less the same as if the bank lent money to someone (except with a bias towards legibility). Sometimes I buy stuff, but then the person I bought something from now has an extra $1. It doesn’t really make sense to talk about money being “in” financial assets, in the way you are imagining.

You are right that the fed is significantly increasing total financial wealth. But not 20x the amount that’s “needed.” (Also, 5% would be way too high an estimate if this was how it worked.)

Derivatives, bonds, treasury notes, stocks, etc. I used the general case because there aren’t any rules about it, as distinct from the Savings and Loans model of banking. In that case, the central bank makes money available, the bank loans out all of it, and ~100% of the money loaned gets spent on things on the CPI.

I am skeptical that buying something like a tranche of repackaged loans is effectively the same as issuing loans. For example, consider the 2008 crises; bailout money was made available to financial institutions so that they would make it available as credit. Instead that money was spent short-term-gain investments (like stocks) and the shortage of credit extended longer than it needed to.

Do you know a good source where they actually trace the transaction chain and identify where the money is spent on the things the Fed wants it spent on? All I can find are cutesy videos and papers which only talk about one stage of the process.

Consider the set of bonds issued and held. The number issued is equal to the number held. If I increase the number held by 1, then I will bid up the price of bonds, both decreasing the # held by other people (since more expensive bonds are less attractive to hold) and increasing the # issued (since more expensive bonds are more attractive to issue). Those two effects must add up to 1.

If I increase the number of bonds issued, that means someone new has a loan.

If I decrease the number of bonds held, then that means someone else was going to buy a loan and instead they didn’t. That means they spent the money on something else, or perhaps left it under their mattress.

Either way, the money gets out of the financial system.

Temporarily setting aside the fact that “don’t save” is a perfectly valid way of getting money out of the financial system, that has a similar effect on inflation: your implicit position seems to be that if try to buy a bond, the effect will just be to stop someone else from holding a bond rather than from causing any new bonds to be issued. I.e., that if I decrease the interest rates on a bond by 0.01%, that has a much (>20x) larger effect on decreasing people’s willingness to hold bonds than on increasing their willingness to issue bonds. That’s true over the very short term, since taking out a loan takes longer than selling a loan, but an extremely strange view over the medium term. It also seems to contradict observed behaviors where people, and especially firms, consider interest rates before taking out a loan (in fact, that effect seems much stronger than the effect of interest rates on savings).

Also, note that the same substitution effect happens when I make a loan. If I hadn’t loaned Alice money, she would have taken out a loan from someone else. Does anything have any effect on the world?

This makes sense, but doesn’t address my concern. All loans are not equal in their effects on the consumer spending CPI tries to track, and therefore on inflation. Car loans are spent on cars. Home loans are spent on homes. Loans of different types are spent on different things, which may or may not be on the CPI. The problem is from the perspective of financial institutions they are all substitutes. To the extent that bonds which do not directly affect the CPI compete with bonds that do (say a loan for speculating on stocks vs. a loan for a car), I suspect more money is being injected than necessary. (I speculate) this leaves the surplus as asset inflation. This is what I was imagining when I said ‘stays in the financial system’.

Reflecting on the savings point, I also note that the overhead costs (the fees and such that make up the salaries of financial employees) go overwhelmingly to people who have a high savings rate, invest in financial instruments, and pay the most in taxes.

I note that there are plenty of reasons to think the current system is good apart from asset inflation. I also have no real sense how fast the transactions take place—as you point out, it is quite fast to sell a loan—so if it turns out that all money eventually hits stuff on the CPI and the money velocity is high enough, I would be persuaded this is not a problem. I could also be persuaded by seeing something which shows (or at least describes) the inflows/outflows of money with respect to the Fed and goods by which inflation is tracked. My google-fu has failed me to date.