The Felt Sense: What, Why and How

While LW has seen previous discussion of Focusing, I feel like there has been relatively limited discussion of the felt sense—that is, the thing that Focusing is actually accessing.

Everyone accesses felt senses all the time, but most people don’t know that they are doing it. I think that being able to make the skill more explicit is really valuable, and in this post I’m going to give lots of examples of why that is and what you can do with it.

Hopefully, after I’m done, you will not only know what a felt sense is (if you didn’t already), but also will have difficulty understanding how you ever got by without this concept.

Examples of felt senses

The term “felt sense” was originally coined by the psychologist Eugene Gendlin, as a name for something that he found his clients to be accessing in their therapy sessions. Here are some examples of felt senses:

Think of some person you know, maybe imagining what it feels to be like in the same room as them. You probably have some “sense” of that person, of what it is that they feel like.

Likewise if you think of some fictional universe, it has something of its own feel. Harry Potter feels different from Star Wars feels different from Game of Thrones feels different from James Bond.

Sometimes you will have a word “right on the tip of your tongue”; it’s as if the word is almost there, but you can’t quite reach it. When you do, you just know that it’s the right word—because the “shape” of the word matches the one you were reaching for before.

The felt senses of pictures

Here are are a few pictures that I recently collected from the Facebook group “Steampunk Tendencies”:

How do you feel when you look at these pictures? What’s the general vibe that unites all of these pictures?

Likely you can find quite a few. If I put aside the words “steampunk” and “Victorian”, next I get the word “mechanical”. “Dark” also feels fitting.

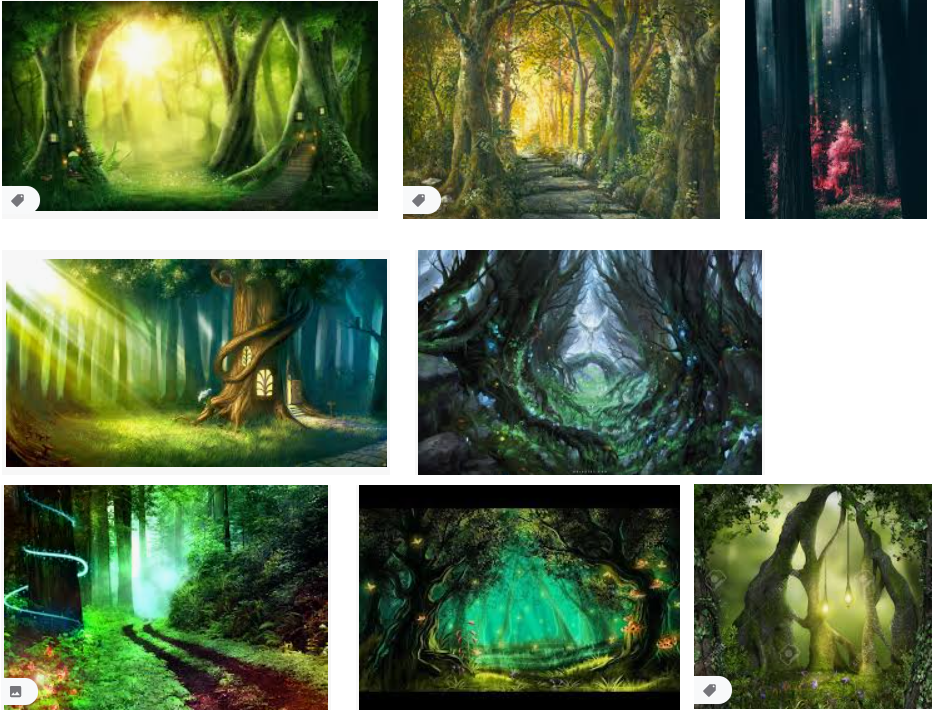

Whatever the vibe that you get, it’s probably something different than the one you get from this collection of images:

Look at the first set of images, then the second. How does it feel when you switch looking from one to the other? What kinds of changes are there in your mind and your body?

I like both sets, but looking from one to the other, I notice that the forest images make me feel like my mind is opening up, whereas the steampunk ones make it close a little. Comparing the two, I feel like there’s some slightly off-putting vibe in the steampunk set, that makes me prefer looking at the forest images—which I would not have noticed if I hadn’t viewed them side to side. (I am guessing that some readers will have the opposite experience, of finding the forest ones off-putting compared to the steampunk ones.)

Emotional and mental states as felt senses

Internal emotional and mental states can also have their own felt senses. That shouldn’t be very surprising, since your experience of e.g. a set of pictures is an internal mental state. Here are a few examples of felt senses from alkjash:

When I solve a problem in a creative way (e.g. fix posture by turning in the shower), there’s a sensation of enlightenment at the back of my head which literally feels like my skull is opening up. The words to this feeling are “I’ve discovered a new dimension!”

I sometimes sit slouched over in bed for hours at a time browsing Facebook or Reddit, playing video games, or binge-watch a season of a TV show. After getting up from the slouch, my whole body is enveloped in a haze of laziness and decay. The zombie haze is thickest inside my ribs. The words to this pressure are “Symptoms of the spreading corruption.”

A piece of my social anxiety forms a hard barrier that pushes against the center of my chest. I learned the words to this feeling from a post by Zvi: “Conform! Every time you walk outside the norm, think about the implicit accusation you’re making against everyone who didn’t try it.”

Sometimes it’s easy to come up with words to describe a felt sense, but typically it takes a bit of time to find exactly the right ones. I expect that it took some time for alkjash to find evocative descriptions such as the above.

Here’s Duncan Sabien describing the experience of honing down on a particular felt sense (I’ve edited out some excellent elaborations and pictures that were included between these lines; the whole post is recommended reading):

Okay, so there’s clearly SOMETHING bothering me. And it’s got something to do with Cameron.

Have we been fighting a lot?

No, that’s not it at all.

It’s more like — like — ugh, like I never know what to say?

No, it’s like I have to say the right things, or else.

It’s like — if I say the wrong thing, then everything falls apart and it’s all ruined.

And it’s like I’m the only one? Like, Cameron doesn’t have to pay attention, just me. Cameron gets to —

— to —

— to relax. That’s it. Yeah. It feels like I’m the only one who doesn’t get to relax.

Felt sense as the layer below language

Mark Lippmann, in his document “Folding” (currently deprecated) proposes that the felt sense (or the felt meaning, as he calls it) exists as a layer of information “below” language. He gives the following examples:

Pick a word, such as “yogurt”, and say it many times over: “yogurt, yogurt, yogurt...”. Now eventually it may feel like the word has “lost its meaning”; the verbal handle of “yogurt” has become disconnected from the felt sense it used to be associated with.

It’s not just individual words that are connected to felt senses; you can also know the meaning of a sentence that you just read, or have a sense of what a particular paragraph was saying.

Sometimes, if you are working on a document close to a deadline or trying to read something when you are tired, you may find that the thing becomes “slippery”. Your eyes might repeatedly pass over the same words, but you don’t understand what they are saying. You are failing to extract the felt sense holding the meaning of the text.

He notes that a felt sense can also be experienced as a thing or place to return to:

When you say something, and it doesn’t come out right, you try again. Where your mind goes before you try again, that’s felt meaning.

When someone says, can you explain that in different words? Your mind goes back to that, in other words, felt meaning.

When someone says, what do you mean by that? Your mind goes back to that, in other words, felt meaning.

When you’re writing something, and it’s hard, what you’re searching for is felt meaning. Where you’re searching is where felt meaning will be.

When you’re writing something, and it’s easy, you’re drawing upon felt meaning.

When you lose your train of thought, you’ve lost your sense of the felt meaning you were speaking from. When you remember what you were saying, the what is felt meaning.

Why learn to tap into felt senses?

Why are felt senses important? Well, a felt sense looks like it’s coming from some deeper information-processing layer in your brain: if you do anything at all (such as read or talk), you are tapping into that layer.

Everyone accesses felt senses all the time. But you can learn to more explicitly pay attention to the fact that you’re doing it, and thus do it more effectively. This has a great number of benefits.

It’s useful for communication

The bits about text and meaning might already have suggested this: you can express yourself most clearly when you have a good handle on the felt sense of your intended meaning. If you’ve ever found yourself saying “no, that’s not quite what I meant, I mean it more like...”, then you’ve been trying to connect with a felt sense better.

Furthermore, different felt senses let you communicate different things. Matt Goldenberg recently interviewed me on what I do when I’m trying to write something that communicates across perspectives. As a result of his questioning, I ended up describing it as something like this; I’ve bolded each occasion when I’ve made reference to a felt sense:

When I see people talking past each other, I get this frustration, like… let’s say someone is trying to explain meditation to someone skeptical. I see the skeptic asking questions, and I can get a sense of what their model is like and which gaps in their model they are trying to fill with those questions. And then the other person doesn’t seem to get that, and says something else. It feels like there are two different perspectives on the issue. They are almost physical shapes with some overlap but which don’t quite align, and I get an urge to build a bridge between them, to get those two perspectives joined together.

So then I start getting some ideas about it, of what kind of an explanation would fit that hole in the skeptic’s model, and what would make those perspectives sync up, and there’s a sense of harmony and beauty in what that finished explanation would feel like. Then I have all of those scattered ideas and I note them down and try to find something that would feel like a unifying framework, where the ideas wouldn’t feel separate from each other but rather be part of a coherent structure. And I try to make use of that unifying framework to write it so that there’s a smooth flow of one idea to the next, so that each thing flows naturally to the next.

And while I’m writing it, I make sure to come back to a sense of my target audience, and try to have a feel of what they would think of my explanation. Sometimes when I’m writing in essay it starts feeling hard to say who I’m writing to, and then I might end up writing something on Twitter or Facebook, where I have a clearer sense of who’s going to read this, and then that might let me make progress.

I hadn’t explicitly thought about it in those terms, but Matt’s poking helped me make more aware of all the felt senses that I was following: and he was explicitly digging them out of me in order to teach them to others. Having them, I can turn them into explicit guidelines to ask myself (or others), such as:

If you need ideas, is there any particular situation whose felt sense gives you ideas, such as getting frustrated by two people failing to communicate and seeing what they could be saying instead?

If you have several ideas, do you feel like you could get a sense of how to explain them in such a way that they flow from one thing to another?

Do you have a clear feeling of who you are writing to? If not, could you get one, such as by writing something on a social media or as a forum post or imagining a specific person reading it?

It’s useful for creating and appreciating art

As an example of different felt senses being useful for communicating different things, Logan Strohl writes about the use of them in art:

Pick an expressive medium. Could be sketching, poetry, music, whatever.

Then, get in touch with a felt sense. You don’t have to name it. But try to get inside of it.

What is “get inside of it”? Right now there’s a tightness in my solar plexus. I can describe it “from the outside” like so: It’s the bottom of a sort of hot, slightly vibrating rod of sensation that goes from my solar plexus to the middle of my throat. The sensation responds to awareness of my immediate auditory environment (I’m in a coffee shop); the solar plexus tightness gets tighter when I pay attention to the tapping of a metal spoon against a metal jar, and starts to wobble a little when I pay attention to the music in the background.

Rather than describing it from the outside, I can also let the felt sense express itself “from the inside”. This is a kind of attentional trick, I think, which seems to involve setting down my personhood story and letting the felt sense consume awareness.

Then, while “inside” of the felt sense, I can begin to act on my creative medium. If I choose (just a few) words, the solar plexus felt sense types this:

wobble siren sharp and hot fight for warming Persian music hold ready parking alarm to protect changing changing changing nothing safe

Logan then goes on to describe the process of drawing a picture from inside the felt sense, letting each line resonate against the felt sense and only draw things which feel true to it.

… this is what artists are actually doing when they create things. They’re doing additional stuff too, because what I’ve described is merely expression, and art is a kind of communication. Communication is a refined form of expression that usually involves design and editing in addition to expression. But I think the unrefined expression is at the core of art.

This matches my experience when I’m doing role-playing or writing fictional characters: each character has their own felt sense, and writing them is often about getting inside that felt sense. Characters may start with a weak felt sense, but “take on a life of their own”, when that sense gets fleshed out and becomes strong enough.

Sometimes I have difficulty expressing a particular character, in which case I have lost my connection to their felt sense—their “essence”, so to speak. On a few occasions, I have intentionally created characters by taking aspects of the felt senses of my friends, and blended them together into a new whole that feels right.

I have also heard of poetry being described essentially as trying to convey a felt sense through words.

I think much of art is basically all about evoking felt senses. If you have that as an explicit concept, you can look at a piece of art that you like, and attempt to describe its felt sense in greater detail. That may help you dig deeper into what about it you like, and make you feel that thing you like more.

It’s good for knowing what you want

Tapping into felt senses associated with the things that you want feels valuable in general. Rossin writes:

I used to think of myself as someone who was very spontaneous and did not like to plan or organize things any more or any sooner than absolutely necessary. I thought that was just the kind of person I am and getting overly organized would just feel wrong.

But I felt a lot of aberrant bouts of anxiety. I probably could have figured out the problem through standard Focusing but I was having trouble with the negative feeling. And I found it easier to focus on positive feelings, so I began to apply Focusing to when I felt happy. And a common trend that emerged from good felt senses was a feeling of being in control of my life. And it turned out that this feeling of being in control came from having planned to do something I wanted to do and having done it. I would not have noticed that experiences of having planned well made me feel so good through normal analysis because that was just completely contrary to my self-image. But by Focusing on what made me have good feelings, I was able to shift my self-image to be more accurate. I like having detailed plans. Who would have thought? Certainly not me.

Once I realized that my self-image of enjoying disorganization was actually the opposite of what actually made me happy I was able to begin methodically organizing and scheduling my life. Since then, those unexplained bouts of anxiety have vanished and I feel happier more of the time.

Sometimes I get the feeling that a thing that I’m doing seems good on paper, but in practice it just feels like a demotivating chore. Often this means that the thing that I think I’m going for is not the thing that my brain is actually optimizing for, and it’s predicting that the project in question will not fulfill its actual optimization goal. If I can then lean into the felt sense of what I actually want, then I will feel more motivated to pursue it.

For example, recently I have been trying to debug my aversion towards dating sites. There seem to be several components to that aversion, but one in particular is a vibe of “I don’t expect this to really work” that I tend to get at the point when I start to browse other people’s profiles.

Which raised the question of… doesn’t work for what, exactly? Not just “for getting into a relationship”; what’s the deeper desire that makes me want a relationship in the first place?

So far I had been kind of waffling back and forth on the question of “do I want children”, so my search filters had included people with various answers to that question. But then I accidentally ended up doing a search where that answer was required to be “yes”, and noticed that the kinds of profiles I got in response—or just consistently seeing “wants children” on all the results that I got—gave me a much felt sense of this could lead to somewhere promising.

The main thing doesn’t seem to be just the thought of having children, but also something about the potential partners generally being the type of people who want children [due to some personality trait which I haven’t verbalized yet, but which was more apparent in the profiles that I started seeing]… which started making the whole dating site thing seem more appealing again.

In a way, finding this particular felt sense when I was feeling demotivated, feels like the same kind of thing as finding “who was my target audience for this piece of writing again” when I’ve been feeling demotivated by writing. In either case the brain is pursuing some optimization target, but cannot proceed and reacts by demotivation if a clear optimization target cannot be found.

Michael Smith (Valentine) has recently been talking about leaning into pleasure, and of how society tends to cause psyches to be built around avoiding pain rather than pursuing joyful bright desire. I’m coming to agree with Rossin’s post in that we probably tend to undervalue using felt senses to look into the positive, and don’t pursue the “bright desire” as much as we could—in part because we haven’t spent time really digging into the felt senses of enjoyment. (Though it needs to be stated that often one’s mind has reasons for why it considers it necessary to feel bad, so it does often make sense to investigate those reasons first.)

Generally, your aesthetics encode information and assumptions about what your brain considers valuable [1 2 3]. Aesthetics are to a large extent expressed in felt senses.

It’s useful for figuring out what’s bothering you

The “standard” use for the felt sense, from Gendlin’s original book, is figuring out what bothers you. Duncan Sabien already gave us an example of this previously, when figuring out why an imaginary “Cameron” was bothering him. Listening to felt senses is the foundation of Focusing-Oriented Psychotherapy, as well as practices such as Internal Double Crux, Internal Family Systems, Coherence Therapy, and experiential forms of therapy in general.

This excerpt from Unlocking the Emotional Brain described “Richard” getting in contact with a felt sense of what his mind thought would happen if he expressed confidence:

Richard: Now I’m feeling really uncomfortable, but-it’s in a different way.

Therapist: OK, let yourself feel it—this different discomfort. [Pause.] See if any words come along with this uncomfortable feeling.

Richard: [Pause.] Now they hate me.

Therapist: “Now they hate me.” Good. Keep going: See if this really uncomfortable feeling can also tell you why they hate you now.

Richard: [Pause.] Hnh. Wow. It’s because… now I’m… an arrogant asshole… like my father… a totally self-centered, totally insensitive know-it-all.

Therapist: Do you mean that having a feeling of confidence as you speak turns you into an arrogant asshole, like Dad?

Richard: Yeah, exactly. Wow.

As a result of having surfaced this felt sense, Richard was then able to question it and revise the belief contained in it.

It helps you know when you are triggered

I think of “being triggered” meaning something like “a part of you tries to force a particular outcome even if your other parts would disagree of this being a good idea” (this feels closely related to the Buddhist notion of craving for specific outcomes).

If I think about situations where I wish I had acted differently, they include things like

I told my cousin that I was interesting in moving something closer to psychology, career-wise. My cousin said something that I thought implied she didn’t think I knew much about psychology, reflecting a very old model of me. I felt a strong desire to correct that misconception, and there was something of a sharp forcefulness in that response, trying to force her into thinking the right thing.

I overheard some parents treating their child in a way that felt to me hurtful towards the child, and there was a desire to intervene and force them to act differently towards their child. (But of course I knew that it wouldn’t do any good.)

I got a message that I would have preferred not to receive or read, but for as long as it remained unread, there was an insistent tugging, as if something was trying to force it to become read, and another something trying to force it not to be read.

Besides the specific and somewhat different felt senses in all three of those situations, there’s also a shared general felt sense of… some sort of wrongness, as if my mind feels that there is something wrong about the world, which needs to be fixed. As long as that part is trying to force that fix, I can’t think or react entirely freely.

When I’m triggered, it’s not always clear to me: I might be so strongly triggered that the thought just seems like absolute truth to me, or the triggering might be subtle enough that it might pass almost unnoticed. But if I pay attention to the sense of wrongness that I typically get when triggered, I can have something of a trigger-action plan of “notice when I am triggered, and pause to see what the appropriate response could be”.

The opposite of the wrongness of being triggered feels something like the Internal Family Systems notion of “the 8 Cs of being in Self”: “confidence, calmness, creativity, clarity, curiosity, courage, compassion, and connectedness”. Noticing that I do not have those kinds of felt senses also helps to notice when I’m triggered.

Conclusion

There are a number of explanations of how to do Focusing, that is, tap into your felt senses. Some here on LW include ones by (particularly recommended!) Duncan Sabien, alkjash, and Mark Xu. The Focusing Institute offers this page of six steps, which are further elaborated on Eugene Gendlin’s book.

My personal favorite set of formal Focusing instructions is in Ann Weiser Cornell’s The Power of Focusing; for some reason, everyone always seems to recommend the original Focusing book, even though AWC’s instructions feel ten times better to me.

That said, I always feel like formal Focusing instructions risk making the felt sense feel like this exotic super-special thing, and then you might end up wondering things like “is this really the felt sense” way too much. Remember: the felt sense is nothing special. If you understand what this sentence is saying, you already have access to a felt sense—the one which tells you what the meaning of this sentence is.

Thus, my favored approach to tapping into a felt sense is just “imagine I was explaining this feeling that I have to someone else, taking the time to find the words and description that resonate the most”.

In other words, in explaining felt senses, I would recommend you to go not for the felt sense of “explaining some exotic and special thing deep in my subconscious”, but rather for the felt sense of “explaining a thing in my everyday experience and just wanting to find exactly the right words for it”.

- Noticing Frame Differences by (Sep 30, 2019, 1:24 AM; 218 points)

- My “2.9 trauma limit” by (Jul 1, 2023, 7:32 PM; 195 points)

- Impact obsession: Feeling like you never do enough good by (EA Forum; Aug 23, 2023, 11:32 AM; 161 points)

- Creating a truly formidable Art by (Oct 14, 2021, 4:39 AM; 132 points)

- Book Launch: “The Carving of Reality,” Best of LessWrong vol. III by (Aug 16, 2023, 11:52 PM; 131 points)

- Goodhart’s Law inside the human mind by (Apr 17, 2023, 1:48 PM; 125 points)

- Catching the Spark by (Jan 30, 2021, 11:23 PM; 117 points)

- Voting Results for the 2020 Review by (Feb 2, 2022, 6:37 PM; 108 points)

- Scaffolding for “Noticing Metacognition” by (Oct 9, 2024, 5:54 PM; 88 points)

- Babble & Prune Thoughts by (Oct 15, 2020, 1:46 PM; 80 points)

- Romance, misunderstanding, social stances, and the human LLM by (Apr 27, 2023, 12:59 PM; 75 points)

- Beliefs as emotional strategies by (Apr 9, 2021, 2:28 PM; 75 points)

- 2020 Review Article by (Jan 14, 2022, 4:58 AM; 74 points)

- Acting Wholesomely by (Feb 26, 2024, 9:49 PM; 59 points)

- Fake Frameworks for Zen Meditation (Summary of Sekida’s Zen Training) by (Feb 6, 2021, 3:38 PM; 54 points)

- The three existing ways of explaining the three characteristics of existence by (Mar 7, 2021, 6:20 PM; 40 points)

- Closeness To the Issue (Part 5 of “The Sense Of Physical Necessity”) by (Mar 9, 2024, 12:36 AM; 36 points)

- How predictive processing solved my wrist pain by (Jul 4, 2024, 1:56 AM; 35 points)

- Acting Wholesomely by (EA Forum; Feb 26, 2024, 9:49 PM; 26 points)

- 's comment on Cup-Stacking Skills (or, Reflexive Involuntary Mental Motions) by (Oct 15, 2021, 1:02 PM; 23 points)

- 's comment on The ‘ petertodd’ phenomenon by (Apr 15, 2023, 6:07 AM; 14 points)

- LessWrong Meetup—Gendlin’s Focusing by (Jul 19, 2022, 4:55 PM; 10 points)

- How to reliably signal internal experience? by (Dec 27, 2020, 11:18 AM; 9 points)

- 's comment on Frame Bridging v0.8 - an inquiry and a technique by (Jun 20, 2023, 8:49 PM; 8 points)

- 's comment on Focusing by (Jul 31, 2022, 9:26 AM; 7 points)

- 's comment on Most people should probably feel safe most of the time by (May 9, 2023, 11:50 PM; 7 points)

- 's comment on Shoulder Advisors 101 by (Oct 10, 2021, 8:17 AM; 6 points)

- 's comment on Focusing by (Jul 30, 2022, 1:45 PM; 4 points)

- 's comment on Most people should probably feel safe most of the time by (May 10, 2023, 6:50 PM; 3 points)

This post feels like an important part of what I’ve referred to as The CFAR Development Branch Git Merge. Between 2013ish and 2017ish, a lot of rationality development happened in person, which built off the sequences. I think some of that work turned out to be dead ends, or a bit confused, or not as important as we thought at the time. But a lot of it was been quite essential to rationality as a practice. I’m glad it has gotten written up.

The felt sense, and focusing, have been two surprisingly important tools for me. One use case not quite mentioned here – and I think perhaps the most important one for rationality, is for getting a handle on what I actually think. Kaj discusses using it for figuring out how to communicate better, getting a sense of what your interlocutor is trying to understand and how it contrasts with what you’re trying to say. But I think this is also useful in single-player mode. i.e. I say “I think X”, and then I notice “no, there’s a subtle wrongness to my description of what X is”. This is helpful both for clarifying my beliefs about subtle topics, or for following fruitful trails of brainstorming.