The Problem of the Criterion

I keep finding cause to discuss the problem of the criterion, so I figured I’d try my hand at writing up a post explaining it. I don’t have a great track record on writing clear explanations, but I’ll do my best and include lots of links you can follow to make up for any inadequacy on my part.

Motivation

Before we get to the problem itself, let’s talk about why it matters.

Let’s say you want to know something. Doesn’t really matter what. Maybe you just want to know something seemingly benign, like what is a sandwich?

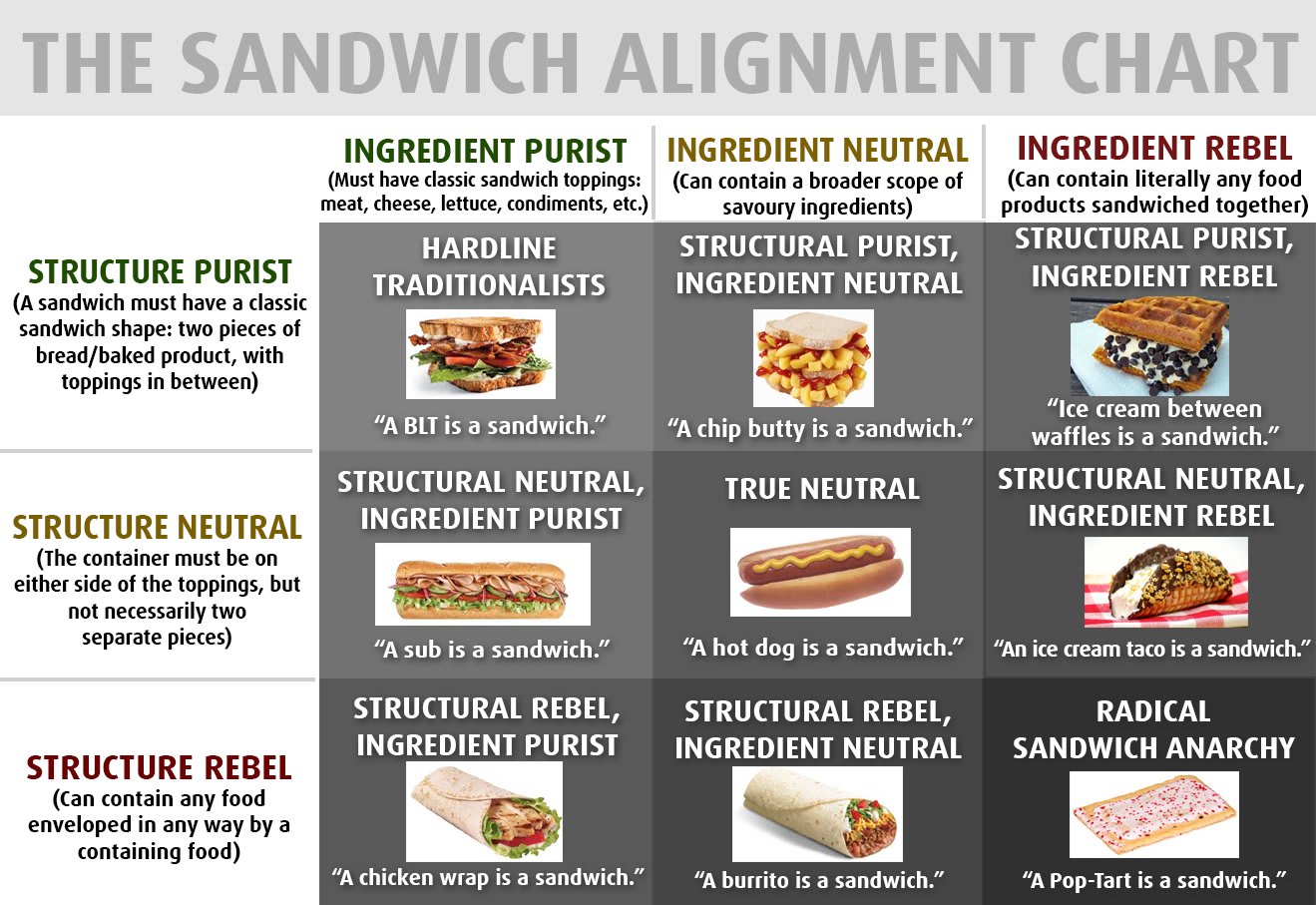

At first this might seem pretty easy: you know a sandwich when you see it! But just to be sure you ask a bunch of people what they think a sandwich is and if particular things are sandwiches are not.

Uh oh...

You’ve run headlong into the classic problem of how to carve up reality into categories and assign those categories to words. I’ll skip over this part because it’s been addressed to death already.

So now you’ve come out the other side accepting that “sandwich”, like almost all categories, has nebulous boundaries, and that there is no true sandwich of which you can speak.

Fine, but being not one easily deterred, you come up with a very precise, that is a mathematically and physically precise, definition of a sandwich-like object you call an FPS, a Finely Precise Sandwich. Now you want to know whether or not something is an FPS.

You check the conditions and it all seems good. You have an FPS. But wait! How do you know each condition is true? Maybe one of your conditions is that the FPS is exactly 3 inches tall. How do you know that it’s really 3 inches tall?

Oh, you used a ruler? How do you know the ruler is accurately measuring 3 inches? And furthermore, how do you know your eyes and brain can be trusted to read the ruler correctly to assess the height of the would-be FPS? For that matter, how do you even know what an inch is, and why was 3 inches the true height of an FPS anyway?

Heck, what does it even mean to “know” that something is “true”?

If you keep reducing like this, you’ll eventually hit bottom and run into this question: how do you know that something is true? Now you’ve encountered the problem of the criterion!

The Problem

How do you know something is true? To know if something is true, you have some method, a criterion, by which you assess its veracity. But how do you know this criterion is itself true? Oh, you have a method, i.e. a criterion, by which you assess its veracity.

Oops! Infinite recursion detected!

The problem of the criterion is commonly attested to originate with the ancient Greek philosopher Pyrrho. Since then interest in it has come in and out of favor. Roderick Chisholm, the modern philosopher who rejuvenated interest in the problem, often phrases it as a pair of questions:

What do we know? What is the extent of our knowledge?

How are we to decide whether we know? What are the criteria of knowledge?

This creates a kind of epistemic circularity where we go round in circles trying to justify our knowledge with our knowledge yet are never able to grab hold of something that itself need not be justified by something already known. If you’re familiar with the symbol grounding problem, it’s essentially the same problem, generalized (cf. SEP on metaphysical grounding).

To that point, the problem of the criterion is really more a category of related epistemological problems that take slightly different forms depending on how they manifest the core problem of grounding justification knowledge. Some other problems that are just the problem of the criterion in disguise:

the problem of perception (and specifically epistemological problems of perception)

metaethical uncertainty (not just normative uncertainty, but uncertainty about what norms are even like)

Really any kind of fundamental uncertainty about what is true, what is known, what can be trusted, etc. is rooted in the problem of the criterion. Thus how we respond to it impacts nearly any endeavor that seeks to make use of information.

Okay, so we have this problem. What to do about it?

Possible Responses

First up, there are no known solutions to the problem of the criterion, and it appears, properly speaking, unsolvable. Ultimately all responses either beg the question or unask, dissolve, or reframe the question in whole or in part. Nonetheless, we can learn something from considering all the ways we might address it.

Chisholm argues that there are only three possible responses to the problem: particularism, methodism, and skepticism. I’d instead say there are only three ways to try to solve the problem of the criterion, and other responses are possible if we give up finding a proper solution. As mentioned, all these attempts at solutions ultimately beg the question and so none actually resolve the problem—hence why it’s argued that the problem is unsolvable—but they are popular responses and deserve consideration to better understand why the problem of the criterion is so pernicious.

Particularism is an attempt to resolve the problem of the criterion by picking particular things and declaring them true, trusted, etc. by fiat. If you’ve ever dealt with axioms in a formal system, you’ve engaged in a particularist solution to the problem of the criterion. If you’re familiar with Wittgenstein’s notion of hinge propositions, that’s an example of particularism. My impression is that this is widely considered the best solution since, although it leaves us with some number of unverified things we must trust on faith, in practice it works well enough by simply stopping the infinite regress of justifications at some point past which it doesn’t matter (more on the pragmatism of when to stop shortly). To paraphrase Chisholm, the primary merit of particularism is that the problem of the criterion exists yet we know things anyway.

Methodism tries to solve the problem of the criterion by picking the criterion rather than some axioms or hinge propositions. Descartes is probably the best known epistemic methodist. The trouble, argues Chisholm and others, is that methodism collapses into particularism where the thing taken on faith is the criterion! Therefore we can just ignore methodism as a special case of particularism.

And then there’s skepticism, arguably the only “correct” position of Chisholm’s three in that it’s the only one that seemingly doesn’t require assuming something on faith. Spoiler alert: it does because it still needs some reason to prefer skepticism over the alternatives, thus it still ends up begging the question. Skepticism is also not very useful because even though it might not lead to incorrectly believing that a false thing is true, it does this by not allowing one to believe anything is true! It’s also not clear that humans are capable of true skepticism since we clearly know things, and it seems that perhaps our brains are designed such that we can’t help but know things, even if they are true but believed without properly grounded justification. So, alas, pure skepticism doesn’t seem workable.

Despite Chisholm’s claim to those being the only possible responses, some other responses exist that reject the premise of the problem in some way. Let’s consider a few.

Coherentist responses reject the idea that truth, knowledge, etc. must be grounded and instead seek to find a way of balancing what is known with how it is known to form a self-consistent system. If you’re familiar with the method of reflective equilibrium (SEP), that’s an example of this. Arguably this is what modern science actually does, repeatedly gathering evidence and reconsidering the foundations to produce something like a self-consistent system of knowledge, though at the price of giving up (total) completeness (LW, SEP).

Another way of rejecting the premise is to give up the idea that the problem matters at all via epistemic relativism. In its strongest form, this gives up both any notion of objectivity or intersubjectivity and simply accepts that knowledge is totally subjective and ultimately unverifiable. In practice this is a kind of attractor position for folks burnt out on there-is-only-one-ontology scientism who overcorrect too far in the other direction, and although some of the arguments made for relativism are valid, complete rejection or even heavy devaluing of intersubjectivity makes this position essentially a solipsistic one and thus, like extreme skepticism, not useful for much.

Finally, we come to a special case of particularist responses known as pragmatism, and it’s this kind of response that Yudkowsky offered. The idea of pragmatism is to say that there is some purpose to be served and by serving that purpose we can do an end-run around the problem of the criterion by tolerating unjustified knowledge so long as it works well enough to achieve some end. In Yudkowsky’s case, that end is “winning”. We might summarize his response as “do the best you can in order to win”, where “win” here means something like “live a maximally fulfilling life”. I’d argue this is basically right and in practice what most people do, even if their best is often not very good and their idea of winning is fairly limited.

Yet, I find something lacking in pragmatic responses, and in particular in Yudkowsky’s response, because they too easily turn from pragmatism to motivated stopping of epistemic reduction. If pragmatism becomes a way to sweep the problem of the criterion under the rug, then the lens has failed to see its own flaws. More is possible if we can step back and hold both the problem of the criterion and pragmatism about it simultaneously. I’ll try to sketch out what that means.

Holding the Problem

At its heart, the problem of the criterion is a problem by virtue of being trapped by its own framing. That is, it’s a problem because we want to know about the world and understand it and have that knowledge and understanding fit within some coherent ontological system. If we stopped trying to map and model the world or gave up on that model being true or predictive or otherwise useful and just let it be there would be no problem.

We’re not going to do that, though, because then we’d be rocks. Instead we are optimization processes, and that requires optimizing for something. That something is what we care about, our telos, the things we are motivated to do, the stuff we want, the purposes we have, the things we value, and maybe even the something we have to protect. And instrumental to optimization is building a good enough map to successfully navigate through the territory to a world state where the something optimized for is in fact optimized.

So we’re going to try to understand the world because that’s the kind of beings we are. But the existence of the problem of the criterion suggests we’ve set ourselves an impossible task that we can never fully complete, and we are forced to endeavor in it because the only other option is ceasing to be in the world. Thus we seem inescapably trapped by the tension of wanting to know and not being able to know perfectly.

As best I can tell, the only way out is up, as in up to a higher frame of thinking that can hold the problem of the criterion rather than be held by it. That is, to be able to simultaneously acknowledge that the problem exists, accept that you must both address it and by virtue of addressing it your ontology cannot be both universal and everywhere coherent, and also leave yourself enough space between yourself and the map that you can look up from it and notice the territory just as it is.

That’s why I think pragmatism falls short on its own: it’s part of the response, but not the whole response. With only a partial response we’ll continually find ourselves lost and confused when we need to serve a different purpose, when we change what we care about, or when we encounter a part of the world that can’t be made to fit within our existing understanding. Instead, we need to deal with the fundamental uncertainty in our knowledge as best we can while not forgetting we’re limited to doing our best while falling short of achieving perfection because we are bounded beings who are embedded in the world. Doing so cultivates a deep form of epistemic humility that not only acknowledges that we might be mistaken, but that our very notion of what it means to be mistaken or correct is itself not fully knowable even as we get on with living all the same.

NB: Holding the problem of the criterion is hard.

Before we go further, I want to acknowledge that actually holding the problem of the criterion as I describe in this section is hard. It’s hard because successfully doing what I describe is not a purely academic or intellectual pursuit: it requires going out into the world, actually doing things that require you to grapple with the problem of the criterion, often failing, and then learning from that failure. And even after all that there’s a good chance you’ll still make mistakes all the time and get confused about fundamental points that you understand in theory. I know I certainly do!

It’s also not an all at once process to learn to hold the problem. You can find comments and posts of mine over the past few years showing a slowly building better understanding of how to respond to the problem of the criterion, so don’t get too down on yourself if you read the above, aspire to hold the problem of the criterion in the way I describe, and yet find it nearly impossible. Be gentle and just keep trying.

And keep exploring! I’m not convinced I’ve presented some final, ultimate response to the problem, so I expect to learn more and have new things to say in time. What I present is just as far as I’ve gotten in wrangling with it.

Implications

Having reached the depths of the problem of the criterion and found a way to respond, let’s consider some places where it touches on the projects of our lives.

A straightforward consequence of holding the problem of criterion and adopting pragmatism about it is that all knowledge becomes ultimately teleological knowledge. That is, there is always some purpose, motivation, or human concern behind what we know and how we know it because that’s the mechanism we’re using to fix the free variable in our ontology and choose among particular hinge propositions to assume, even and especially if those propositions are implicit. Said another way, no knowledge is better or worse without first choosing the purpose by which knowledge can be evaluated.

This is not a license to believe whatever we want, though. For most of us, most of the time, our purpose should probably be to believe that which best predicts what we observe about the world, i.e. we should believe what is true. The key insight is to not get confused and think that a norm in favor of truth is the same thing as truth being the only possible way to face reality. The ground of understanding is not solid, so to speak, and if we don’t choose to make it firm when needed it will crumble away beneath our feet.

Thus, the problem of the criterion is also, as I hope will be clear, a killer of logical positivism. I point this out because logical positivism is perennially appealing, is baked into the way science is taught in schools, and has a way of sneaking back in when one isn’t looking. The problem of the criterion is not the only problem with logical positivism, but it’s a big one. In the same way, the problem of the criterion is also a problem for direct realism about various things because the problem implies that there is a gap between what is perceived and the thing being perceived and suggests the best we can hope for is indirect realism, assuming you think realism about something is the right approach at all.

Finally, all this suggests that dealing with knowledge and truth, whether as humans, AIs, or other beings, is complicated. Thus why we see a certain amount of natural complexity in trying to build formal systems to grapple with knowledge. Real solutions tend to look like a combination of coherentism and pragmatism, and we see this in logical induction, Bayesian inference, and attempts to implement Solomonoff induction. This obviously has implications for building aligned AI that are still being explored.

Recap

This post covered a lot of ground, but I think it can be summarized thusly:

There is a problem in grounding coherent knowledge because to know something is to already know how to know something.

This circularity creates the problem of the criterion.

The problem of the criterion cannot be adequately solved, but it can be addressed with pragmatism.

Pragmatism is not a complete response because no particular pragmatism is privileged without respect to some purpose.

A complete response requires both holding the problem as unsolvable and getting on with knowing things anyway in a state of perpetual epistemic humility.

The implications of necessarily grounding knowledge in purpose are vast because the problem of the criterion lurks behind all knowledge-based activity.

- Circular Reasoning by (Aug 5, 2024, 6:10 PM; 91 points)

- Three enigmas at the heart of our reasoning by (Sep 21, 2021, 4:52 PM; 56 points)

- Zen and Rationality: Equanimity by (Aug 16, 2021, 4:51 PM; 30 points)

- Seeking Truth Too Hard Can Keep You from Winning by (Nov 30, 2021, 2:16 AM; 27 points)

- The Map-Territory Distinction Creates Confusion by (Jan 4, 2022, 3:49 PM; 25 points)

- Why the Problem of the Criterion Matters by (Oct 30, 2021, 8:44 PM; 24 points)

- Fundamental Uncertainty: Prelude by (Feb 6, 2022, 2:26 AM; 19 points)

- The Purpose of Purpose by (May 15, 2021, 9:00 PM; 17 points)

- 's comment on Grokking the Intentional Stance by (Sep 1, 2021, 5:23 AM; 12 points)

- Identity in What You Are Not by (Apr 24, 2021, 8:11 PM; 11 points)

- The Problem of the Criterion is NOT an Open Problem by (Jan 6, 2022, 4:31 PM; 9 points)

- 's comment on Exercise: Taboo “Should” by (Jan 23, 2021, 1:17 AM; 8 points)

- 's comment on Grokking the Intentional Stance by (Aug 31, 2021, 5:30 PM; 8 points)

- Epistemic Circularity by (May 23, 2018, 9:00 PM; 8 points)

- 's comment on No Abstraction Without a Goal by (Jan 11, 2022, 12:43 AM; 7 points)

- 's comment on Are many EAs philosophical pragmatists? by (EA Forum; Aug 30, 2021, 4:33 PM; 5 points)

- 's comment on Saving Time by (May 18, 2021, 11:31 PM; 4 points)

- 's comment on Three enigmas at the heart of our reasoning by (Sep 27, 2021, 4:53 AM; 4 points)

- 's comment on The Teleological Mechanism by (Jan 22, 2021, 4:04 AM; 4 points)

- 's comment on Teaching ML to answer questions honestly instead of predicting human answers by (May 28, 2021, 8:50 PM; 3 points)

- 's comment on The No Free Lunch theorem for dummies by (Dec 6, 2022, 9:17 PM; 2 points)

- 's comment on The Nature of Counterfactuals by (Jul 20, 2021, 8:11 PM; 2 points)

- 's comment on The Nature of Counterfactuals by (Jul 17, 2021, 8:32 PM; 2 points)

- 's comment on Probability theory and logical induction as lenses by (May 9, 2021, 4:21 PM; 2 points)

- 's comment on Arguments for moral indefinability by (Oct 2, 2023, 4:41 PM; 0 points)

This all seems to rest on an idea that an empty box labeled “truth” was dropped in my lap in the platonic land of a priori mental emptiness, and I’m obligated to fill it with something before I’m allowed to begin thinking. But obviously, that’s not what happened. Rather, as I grew up, the abstract label called “truth” was invented and refined by me to help me make sense of the world and communicate with (or win approval from) others. So I end up at the same answer, pragmatism, but I deny that there was ever any problematic circularity. The problem instead seems to come from a notion of transcendent epistemic justification which is unmotivated and flawed—what good does this idea of justification do? What’s the problem if I do something without justification?

So it would seem at first, but “truth” is just one place the problem of the criterion shows up. It’s the classical version, yes, and that version did have a rather outdated notion of what truth is, but we can also just talk in terms of knowledge and belief and prediction and the problem continues to exist.

Do you ever claim that things are true?

Yes, but only in the sense that by my best efforts, using the brain I actually have, I believe the thing to be the case.

Yes, you can deal with the problem of the criterion by adopting modest epistemology. But that is different from saying there is no problem.

I wouldn’t guess that I have a big disagreement with you once we translate everything into each other’s preferred way of speaking. I think you’re pointing at something important and right. But I sure won’t habitually call it “the problem of the criterion”, or use any of the explanatory devices presented here.

So, let’s see what you think of my take.

I think “The Problem of the Criterion” as framed here (and, I guess, most places) creates a heavy temptation to conflate several different issues.

The problem of responding to the skeptic. The way the problem of the criterion is phrased uses “knowledge”, which tempts one to think of perfect knowledge. This makes the problem seem acute, because plausibly, nothing can be known with certainty. But this makes it sound as if the alternative to solving the problem of the criterion is falling into complete skepticism. For Bayesians (and some other epistemologies), it would be fine if nothing is known with certainty, and indeed, plausibly nothing is known with certainty. This makes the problem of the criterion sound irrelevant, for these camps. And it is, provided we understand the problem of the criterion to be something like “how can we know anything with certainty?”

The epistemic circularity of foundationalism. This is the recursion problem you mention. This is only a problem if you think each belief should have a justification, and these justifications should never form a circle, and should also avoid forming an infinite chain. But there is no mathematical structure which contains no circles, no infinite chains, and also no unjustified orphan truths! This is intuitively a real problem, since we can separately justify intuitions that each belief should be justified, that circular justifications don’t count, and that infinite backward chains of justification also don’t count. I think Eliezer’s answer to this conundrum is correct (the one which you classify as pragmatism), although I think there are some details to work out. (IE, I don’t think most people walk away from that essay with a working classifier to distinguish between bad circular arguments and acceptable ones, because it doesn’t give one; it focuses on making the case that specific instances of apparently circular reasoning are fine and good.)

The naturalistic question, where does knowledge come from? There’s a phenomenon in the world: sometimes people (and animals) seem to know things (and, sometimes not). How does this happen? How can we accurately describe and analyze the phenomenon? Again, Bayesians will tend to think they have a good answer. But this time the Bayesians will be roused to answer with vim and vigor; for this is an issue of key interest to them. Whereas problem #1 seems like a silly distraction to them.

The normative question: what should we consider ourselves to know, and how should we manage belief? This is the core question of epistemic rationality.

You also mention several other distinct problems which “are just the problem of the criterion in disguise”:

You seem to find it encouraging that the Problem of the Criterion mixes all of these problems together in one big pot. I think it’s quite problematic. In particular, it means that people who think they have solved one problem here will think they’ve solved the others. It also tempts impossibility proofs for solving one problem to be applied to the others.

I think you start out discussing the normative problem:

This how do you know sounds like a justification question, rather than an empirical how-did-you-come-to-know; although it’s impossible to tell for sure without specific disambiguation (this is part of the problem).

But then you mix in the recursion problem. At the beginning of the section “The Problem”, your characterization of The Problem is as follows:

So which problem is it?

If it’s the literal, empirical content of the first question asked, how do you know something is true, then we investigate by trying to remember how we know specific things, noticing when we learn new things, and inventing theoretical frameworks (such as positivism, or fallibilism, or probability theory, or neuroscience) which attempt to characterize the process. The recursive issue isn’t so much a problem as it is more data—as we arrive at tentative conclusions about how we come to know things, we can check whether our theories properly account for how we would learn those theories themselves.[1]

If it’s the normative version of the first question, how should we know things (or perhaps, how can we justify knowledge), then the recursion problem is perhaps an argument for why the question is difficult—but not the question itself. On this reading, any answer to the criterion problem must deal with the recursion problem, but dealing with the recursion problem is not in itself sufficient; we might be able to dismiss the recursion problem while lacking any reply to the full problem.

If it’s the recursive problem itself, then the criterion problem is really only a problem for foundationalists; perhaps it should be remembered as the main problem with foundationalism.

If it’s the problem of how we come to know anything (know with certainty), then the skeptical response seems totally reasonable and indeed correct. In this case the recursion problem sounds like just one way to argue for the skeptical conclusion.[2]

EDIT

It looks like, according to Wikipedia,

So it would seem that the regress argument is kept distinct from the problem of the criterion, leaving my other three interpretations on the table.

However, the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy begins its article like this:

Which, indeed, sounds like the regress argument.

And a bit later in the article, a severe ambiguity is confirmed:

This means the recursion problem does have an interesting role to play in the empirical inquiry. The recursion becomes an interesting test case. Perhaps it becomes a big obstacle to some theories. For example, I’ve heard the accusation that Popperian falsifiability theory isn’t itself falsifiable. But perhaps this is simply because it’s better viewed as a normative theory of science, rather than an empirical one.

The empirical-recursive problem of the criterion for Bayesian behavioral scientists (aka economists) is the question of whether we can empirically justify bayesian rationality as a behavioral theory (aka, behavioral economics).

The empirical-recursive problem of the criterion for neuroscience would be whether a particular neuroscientific theory can account for neuroscience as an activity of the brain. (EG, some connectionist theories which require pre-existing concept cells for every concept will fall short, because a pre-existing ‘connectionism cell’ is arguably too implausible.)

In this case, the recursion problem can be properly highlighted by appealing to Godel’s incompleteness theorem, since Godel’s theorem does apply to this kind of crisp 100% knowledge (provided we think it meets the other conditions for the theorem).

However, the kind of skeptic I’m endorsing (a moderate bayesian skeptic, who believes in probabilistic knowledge) has no business making the recursion-problem argument, since they don’t accept the foundationalist underpinnings of such an argument.

But perhaps that’s fine; there’s a long tradition in skepticism of referring to arguments as ladders which you use to climb up to the skeptical vantage point, but then kick down, having no further use for them.

After all, the bayesian moderate-skeptic is simply trying to argue that logical certainty doesn’t exist in practice. So long as they’re arguing about absurdities, they might as well also assume the absurd foundationalist assumptions.

But it’s a bit rude of them if they try to sneak the assumptions in without explicitly flagging them.

First, this is a great, really thoughtful comment.

My initial thought is that I’m doing a bad job in this post of pointing at the thing that really matters, which is why I think we may see different framings as useful. I see the problem of the criterion as a particular instance of exposing a deeper, fundamental meta-fact about our world, which is that uncertainty is fundamental to our existence and all knowledge is teleological. I don’t think all that comes through here because when I wrote this it was my first time really trying to explain fundamental uncertainty, so I only go so far in explaining it. I got a bit too excited a confused the problem of the criterion for fundamental uncertainty itself.

That (1) seems boring to Bayesians et al. seems fine to me because they already buy that things are fundamentally uncertain, although I think in practice most aspiring Bayesians don’t really know why, which bleeds into (2). I see (2) as important because knowledge does, in fact, ground out in some foundation, and we try hard to make sure that grounding is correct by requiring justifications for our grounding. Personally, the question I’m most interested in is (3), and then considering what implications that has for (1), (2), and (4), though I don’t really have much to say about (4) here other than that one should be fundamentally uncertain and that I think in practice many people trying to work out (4) get confused because they imagine they can achieve justified true belief, or more often with aspiring Bayesians justified true meta-belief even though all object-level beliefs are uncertain.

So my I have to admit my motivations when writing this post were a bit of a mix of yelling at rationalists I meet who are performing rationality but missing this deeper thing that I was also missing out on for a long time and trying to really clarify what this deeper thing is that’s going on.

I know you’re reading some of my other posts, but let me see if I can explain how I actually think about the problem of the criterion today:

We and every dynamic process can be thought of as made up of lots of feedback circuits, and most of those circuits are negative feedback circuits (positive feedback, where it exists, is often wrapped inside a negative feedback circuit because otherwise the universe would be boring and already tiled with something like paperclips). These circuits get information by observing the world and then generating a signal to control the circuit. The process of generating the signal is necessarily lossy, and it’s because we’re going to compress information when generating the signal. As a result, the circuit makes a “choice” about what to signal on, the signal is thus teleological because the signal depends on what purpose the signal has (purpose is an idea in cybernetics I won’t expand here, but basically it’s what the circuit is designed to do), so all the knowledge (information inside the circuits) we have is both uncertain due to compression (and maybe something something quantum mechanics observation, but I don’t think we need to go there) and teleological because circuits impose teleology through their design.

I’ll admit, this is all sort of a weird way to explain it because it hinges on this unusual cybernetic model of the world, so I try to explain myself in other ways that are more familiar to folks. Maybe that’s the wrong approach, but I think it’s reasonable to come at this thing outside in (which is what I do in my book) by addressing the surface level uncertainty first and then peeling back the layers to find the fundamental uncertainty. This post is weird because it’s a bit in the middle.

(I’ll also note there’s an even deeper version of how I think about fundamental uncertainty and teleology today, but I’m not sure I can put it in words because it comes from meditation experience and I can only talk about it in mysterious ways. I think trying to talk about that way of thinking about it is probably more confusing than helpful.)

IMHO the cybernetic picture isn’t weird or uncommon; naively, I expect it to get less pushback.

I think this is what I most want to push back on. My own sense is that you are confused about this. On my understanding, you seem to simultaneously believe that the core foundationalist assumptions make sense, and also believe an impossibility argument which shows them to be inconsistent. This doesn’t make sense to me.

My formalization here is only one possible way to understand the infinite-regress problem (although I think it does a good job of capturing the essence of it) -- but, in this formalization, the contradiction is really direct, which makes it seem pretty silly.

I also think the contradictory axioms do capture two intuitions which, like, beginning philosophy majors might endorse.

So I think the infinite regress problem should be explained to beginning philosophers as a warning against these naive assumptions about justification. (And indeed, this is how I was taught.)

But that’s what it is to me. It seems to be something else for you. Like a paradox. You write of proving the impossibility of solution, rather than resolving the problem. You write that we should “hold the problem”. Like, in some sense it is still a problem even after it has been solved.

(Perhaps the seeming contradiction is merely due to the way the criterion problem conflates multiple problems; EG, the naturalistic question of where knowledge comes from is still a live question after the justification-infinite-regress problem has been resolved.)

It makes sense to me to try to spell out the consequences of the infinite-regress problem; they may be complex and non-obvious. But for me this should involve questioning the naive assumptions of justification, and figuring out what it is they were trying to do. On my analysis, a reasonable place to go from there is the tiling agents problem and Vingean reflection. This is a more sophisticated picture of the problems rational agents run into when philosophizing about themselves, because it admits that you don’t need to already know how you know in order to know—you are already whatever sort of machine you are, and the default outcome is that you keep running as you’ve run. You’re not at risk of all your knowledge evaporating if you can’t justify it. However, there is a big problem of self-trust, and how you can achieve things over time by cooperating with yourself. And there’s an even bigger problem if you do have the ability to self-modify; then your knowledge actually might evaporate if you can’t justify it.

But this problem is to a large degree solved by the lack of a probabilistic Lob’s theorem. This means we are in a much better situation with respect to self-trust, vingean reflection, and the tiling agents problem—so long as we can accept probabilistic fallibility rather than needing perfect self-trust.

So in effect, the answer to (a newer and significantly more sophisticated version of) the recursive justification problem is the same as the answer to skepticism which you agreed was right and proper—namely, embracing probabilism rather than requiring certainty.

I expect you’ll agree with this conclusion; the part where I think we have some sort of fuzzy disagreement is the part where you still say things like “I see (2) as important because knowledge does, in fact, ground out in some sort of foundation, and we try to make sure that grounding is correct by requiring justifications for our grounding.” I think there are some different possible ways to spell out what you meant here, but I don’t think the best ones connect with (2) very much, since (2) is based on some silly-in-hindsight intuitions about justification.

Hmm, I’ll have to think about this.

So I think maybe there’s something goin on here where I’m taking too much for granted that formal systems are the best way to figure out what to believe about the world to get an accurate picture of it, and so long as you’re figuring out what to believe using some formal system then you’re forced to ground it in some assumed foundation that is not itself justified. This seems important because it means there’s a lot of interesting stuff going on with those assumptions and how they get chosen such that they cause the rest of the system to produce beliefs that track reality.

But it sounds like you think this is a confused view. I admit I feel a bit differently about things than the way they’re presented in the post, but not entirely, as my comment reflects. I think when I wrote the post I really couldn’t see my way around how to know things without being able to formally justify them. Now I better understand there can be knowing without belief that knowledge is justified or true, but I do think there’s something to the idea that I am still too much captured by my own ontology and not fully seeing it as I see through it, and this causes me to get a bit mixed up in places.

The bit about self-trust is really interesting. To get a little personal and psychological, I think the big difference between me ~4 years ago and me now is that ~4 years ago I learned to trust myself in some big important way that goes deeper than surface level self-trust. On the surface this looks like trusting my feelings and experiences, but to a certain extent anyone can do this if you just give them feedback that says trust those things more than other things. But I’m talking about something a level deeper where I trust the process by which those things get generated to do what they do and that they’re doing their best (in the sense that the universe is deterministic and we’re all always doing our best/worst because it could have been no other way).

If I’m honest I’ve really struggled to understand what’s going on with Lob’s theorem and why it seems like a big deal to everyone. But it seems like from what you’re saying it’s related to the issue that got me started on things, which is how do you deal with the problem of verifying that another agent (which could be yourself at another time) shares your values and is thus in some way aligned with you. If that’s the case maybe I already grasp the fundamentals of this obstacle Lob seems to create and have just failed to realize that’s what folks were talking about when they talk about Lob with respect to aligning AI.

@abramdemski Wanted to say thanks again for engaging with my posts and pointing me towards looking again at Lob. It’s weird: now that I’ve taken so time to understand it, it’s just what in my mind was already the thing going on with Godel, just I wasn’t doing a great job of separating out what Godel proves and what the implications are. As presented on its own, Lob didn’t seem that interesting to me so I kept bouncing off it as something worth looking at, but now I realize it’s just the same thing I learned from GEB’s presentation of Peano arithmetic and Godel when I read it 20+ years ago.

When I go back to make revisions to the book, I’ll have to reconsider including Godel and Lob somehow in the text. I didn’t because I felt like it was a bit complicated and I didn’t really need to dig into it since I think there’s already a bit too many cases where people use Godel to overreach and draw conclusions that aren’t true, but it’s another way to explain these ideas. I just have to think about if Godel and Lob are necessary: that is, do I need to appeal to them to make my key points, or are these things that are better left as additional topics I can point folks at but not key to understanding the intuitions I want them to develop.

I’ve heard Lob remarked that he would never have published if he realized earlier how close his theorem was to just Godel’s second incompleteness theorem; but I can’t seem to entirely agree with Lob there. It does seem like a valuable statement of its own.

I agree, Godel is dangerously over-used, so the key question is whether it’s necessary here. Other formal analogs of your point include Tarski’s undefinability, and the realizablility / grain-of-truth problem. There are many ways to gesture towards a sense of “fundamental uncertainty”, so the question is: what statement of the thing do you want to make most central, and how do you want to argue/illustrate that statement?

I think pragmatism has the problems that the OP points out: it’s necessarily a partial solution , because not everything has a clear winning condition.

Embracing circularity is different from pragmatism. Indeed, without the classifier you mention , it’s completely impractical!

This is why I said “the one which you classify as pragmatism”—Gordon Worley calls it pragmatist because Eliezer’s notion of rationality is ultimately about winning; but that is quite far from being a good summary of Eliezer’s specific argument in Where Recursive Justification Hits Bottom.

I don’t think Eliezer’s specific argument has this problem, since his advice has little to do with winning conditions. His advice is that when considering very abstract questions such as the foundations of epistemology, we have to consider these questions in the same way we consider any other questions, IE using the full strength of our epistemology.

I don’t think there is just one definition of rationality, or that EY has one solution to epistemology.

Winning based rationality doesn’t have to coincide with truth seeking rationality, and there are robust cases where it doesn’t.

The rock bottom argument in no way justifies our epistemic practices, it just says we might as well stick to them.

Using winning based rationality alone entails giving up on every problem that isn’t susceptible to it, including (a)theism, MWI , etc.

Embracing circularity is different to both of the above, and no answer to the the problem of the criterion, since coherence is a criterion.

I think there are a bunch of related problems being labeled as the criterion problem.

One of them is the question: what is the criterion?

The possible answers to this question are (of course) proposed criteria.

For this version of the criterion problem, your objection seems absurd. Of course a proposed answer to the criterion problem is going to be a criterion! That doesn’t disqualify an answer! Rather, that is a necessary characteristic of an answer! We can’t disqualify proposed criteria simply for being criteria!

Another one of them is the infinite-recursion problem Gordon mentions (also known as the regress argument). This argument rests on the foundationalist intuitions that all beliefs need to be justified, and infinite chains of justification (such as circular justification) don’t count.

Coherence seems to also qualify as a possible answer to this version of the criterion problem, addressing the problem by pointing to which of the contradictory assumptions we should give up.

I think rejecting these assumptions is a legitimate sort of answer to the problem, since the criterion problem isn’t just supposed to be a problem within foundationalist theories—it’s not like rejecting those assumptions misses the point of the problem. Rather, the regress argument is an argument made to all thinking beings, for whom the foundationalist assumptions are tacitly supposed to be compelling. So pointing out which assumptions are not, in fact, compelling seems like a good type of reply.

So overall, I don’t buy your argument that coherence is “no answer” to the criterion problem. It seems like a reasonable sort of answer to pursue, for at least two of the central forms of the criterion problem.

Another is: does it work? Another is : does anything work?

Circularity isn’t just a criterion, it’s one of the unholy trinity of criteria …particularism, regress and Circularity .. that are know to have problems. The problem with Circularity is that it justifies too much, not too little.

Coherence is either circularity, in which case it has the same problems; or something else, in which case it needs to be spelt out.

I don’t think EY has spelt out a fourth criterion that works. Where Regress Stops is particularism.

What do you mean by coherence?

What do you mean by coherence?

My take on “justifies too much” is that coherentism shouldn’t just say coherence is the criterion, in the sense of anything coherent is allowed to fly. Instead, the (subjectively) correct approach is (something along the lines of) coherence with the rest of my beliefs.

Coherence is one of the six response types cited in the OP. I was also using ‘circularity’ and ‘coherence’ somewhat synonymously. Sorry for the confusion.

When I took undergrad philosophy courses, “coherentism” and “foundationalism” were two frequently-used categories representing opposite approaches to justifiation/knowledge. Foundationalism is the idea that everything should be built up from some kind of foundation (so here we could classify it as particularism, probably). Coherentism is basically the negation of that, but is generally assumed to replace building-up-from-foundations with some notion of coherence. Neither approach is very well-specified; they’re supposed to be general clusters of approaches, as opposed to full views.

More specifically, with respect to my previous statement:

Here, we can interpret coherentism specifically as the acceptance of circular logic as valid (the inference “A, therefore A” is a valid one, for example—note that ‘validity’ is about the argument from premise to conclusion, and does not imply accepting the conclusion). This resolves the infinite regress problem by accepting regress, whereas particularism instead rejects the assumption that every statement needs a justification.

I think the details of these views matter a whole lot. Which kind of particularism? How is it justified? Does the motivation make sense? Or which coherentism, etc.

The arguments about the Big Three are vague and weak due to the lack of detail. Chisholm makes his attacks on each approach, which sound convincing as-stated, but which seem much less relevant when you’re dealing with a fully-fleshed-out view with specific arguments in its favor.

(But note that for Chisholm, the three are: particularism, methodism, skepticism. So his categorization is different from yours.)

You classify Eliezer as particularism, I see it as a type of circular/coherentist view, Gordon Worley sees need to invent a “pragmatism” category. The real answer is that these categories are vague and Eliezer’s view is what it is, regardless of how you label it.

Also note that I prefer to claim Eliezer’s view is essentially correct without claiming that it solves the problem of the criterion, since I find the criterion problem to be worryingly vague.

That’s how coherence usually works. If no new belief is accepted unless consistent with existing beliefs, then you don’t get as much quodlibet as under pure circular justification, but you don’t get convergence on a single truth either.

Having re-read Where Recursive Justfication Hits Bottom, I think EY says different things in different places. If he is saying that our Rock Bottom assumptions are actually valid, that’s particularism. If he is saying that we are stuck with them, however bad they are it’s not particularism, and not a solution to epistemology.

He also offers a kind of circular defense of induction, which I don’t think amounts to full fledged circularity,because you need some empirical data to kick things off. The Circular Justifcation of Induction isn’t entirely bad, but it’s yet another partial solution, because it’s limited to the empirical and quantifiable. If you explicitly limit everyone to the empirical and quantifiable, that’s logical.positivism, but EY say he’s isn’t a logical positivist.

What are his views, and what is it correct about? Having read them, I still dont know.

It matters both ways. The solution needs to be clear, if there is one.

“Usually” being the key here. To me, the most interesting coherence theories are broadly bayesian in character.

I’m not sure what position you’re trying to take or what argument you’re trying to make here—do you think there’s a correct theory which does have the property of convergence on a single truth? Do you think convergence on a single truth is a critical feature of a successful theory?

I don’t think it’s possible to converge on the truth in all cases, since information is limited—EG, we can’t decide all undecidable mathematical statements, even with infinite time to think. Because this is a fundamental limit, though, it doesn’t seem like a viable charge against an individual theory.

I don’t think he’s saying either of those things exactly. He is saying that we can question our rock bottom assumptions in the same way that we question other things. We are not stuck with them because we can change our mind about them based on this deliberation. However, this deliberation had better use our best ideas about how to validate or reject ideas (which is, in a sense, circular when what we are analyzing is our best ideas about how to validate or reject ideas). Quoting from Eliezer:

And later in the essay:

See, he’s not saying they are actually valid, and he’s not saying we’re stuck with them. He’s just recommending using your best understanding in the moment, to move forward.

I’m also not sure what “a solution to epistemology” means.

Quoting from Eliezer:

So I think it’s fair to say that Eliezer is trying to answer the regress argument. That’s the specific question he is trying to answer. Observing that his position is “not a solution to epistemology” does little to recommend against it.

I think another subtlety which might differentiate it from what’s ordinarily called circular reasoning is a use/mention distinction. He’s recommending using your best reasoning principles, not assuming them like axioms. This is what I had in mind at the beginning when I said that his essay didn’t hand the reader a procedure to distinguish his recommendation from the bad kind of circular reasoning—a use/mention distinction seems like a plausible analysis of the difference, but he at least doesn’t emphasize it. Instead, he seems to analyze the situation as this-particular-case-of-circular-logic-works-fine:

I take this position to be accurate so far as it goes, but somewhat lacking in providing a firm detector for bad vs good circular logic. Eliezer is clearly aware of this:

Bayesianism is even more explicit about the need for compatibility with existing beliefs, I’m priors.

I don’t think there is a single theory that achieves every desideratum (including minimality of unjustified assumptions). Ie. Epistemology is currently unsolved.

I think convergence is a desideratum. I don’t know of a theory that achieves all desiderata. Theres any number of trivial theories that can converge, but do nothing else.

That’s not the core problem: there are reasons to believe that convergence can’t be achieved, even if everyone has access to the same finite pool of information. The problem of the criterion is one of them… if there is fundamental disagreement about the nature of truth and evidence, then agents that fundamentally differ won’t converge in finite time.

Bayesianism is even more explicit about the need for compatibility with existing beliefs, ie. priors.

I don’t think there is a single theory that achieves every desideratum (including minimality of unjustified assumptions). Ie. Epistemology is currently unsolved.

I think convergence is a desideratum. I don’t know of a theory that achieves all desiderata. Theres any number of trivial theories that can converge, but do nothing else. There’s lots of partial theories as well, but it’s not clear how to make the tradeoffs.

That’s not the core problem: there are reasons to believe that convergence can’t be achieved, even if everyone has access to the same finite pool of information. The problem of the criterion is one of them… if there is fundamental disagreement about the nature of truth and evidence, then agents that fundamentally differ won’t converge in finite time.

Yes...the circularity of the method weighs against convergence in the outcome.

Out best ideas relatively might not be good enough absolutely. In that passage he is sounding like a Popperism, but the Popperism approach is particularly unable to achieve convergence.

Doesn’t imply that what he must use is any good in absolute terms.

I was never arguing against this. I broadly agree. However, I also think it’s a poor problem frame, because “solve epistemology” is quite vague. It seems better to be at least somewhat more precise about what problems one is trying to solve.

Well, just because he says some of the things that Popper would say, doesn’t mean he says all of the things that Popper would say.

If you’ve got an argument that a desideratum can’t be achieved, don’t you want to take a step back and think about what’s achievable? In the quoted section above, it seems like I offer one argument that convergence isn’t achievable, and you pile on more, but you still stick to a position something like, we should throw out theories that don’t achieve it?

That’s why I’m using it as an example of coherentism.

IDK what the problem is here, but it seems to me like there’s some really weird disconnect happening in this conversation, which keeps coming back in full force despite our respective attempts to clarify things to each other.

But you also said that:-

Correct about what? That he has solved epistemology, or that epistemology is unsolved, or what to do in the absence of a solution? Remember , the standard rationalist claim is that epistemology is solved by Bayes. That’s the claim that people like Gordon and David Chapman are arguing against. If you say you agree with Yudkowsky, that is what people are going to assume you mean.

I just told you told you what that means “a single theory that achieves every desideratum (including minimality of unjustified assumptions)”

So Yudkowsky is essentially correct about ….something… but not necessarily about the thing this discussion is about.

He says different things in different places, as I said. He says different things in different places, so hes unclear.

I don’t think all desiderata are achievable by one theory. That’s my precise reason for thinking that epistemology is unsolved.

I didn’t say that. I haven’t even got into the subject of what to do given the failure of epistemology to meet all its objectives.

What I was talking about specifically was the inability of Bayes to achieve convergence. You seem to disagree, because you were talking about “agreement Bayes”.

I already addressed this in a previous comment:

I am trying to be specific about my claims. I feel like you are trying to pin very general and indefensible claims on me. I am not endorsing everything Eliezer says; I am endorsing the specific essay.

Is there some full list of desiderata which has broad agreement or which you otherwise want to defend??

I feel like any good framing of “solve epistemology” should start by being more precise than “solve epistemology”, wrt what problem or problems are being approached.

Agreement that you didn’t say that. It’s merely my best attempt at interpretation. I was trying to ask a question about what you were trying to say. It seems to me like one thing you have been trying to do in this conversation is dismiss coherentism as a possible answer, on the argument that it doesn’t satisfy some specific criteria, in particular truth-convergence. I’m arguing that truth-convergence should clearly be thrown out as a criterion because it’s impossible to satisfy (although it can be revised into more feasible criteria). On my understanding, you yourself seemed to agree about its infeasibility, although you seemed to think we should focus on different arguments about why it is infeasible (you said that my argument misses the point). But (on my reading) you continued to seem to reject coherentism on the same argument, namely the truth-convergence problem. So I am confused about your view.

To reiterate: then why would they continue to be enshrined as The Desiderata?

I mean, looking back, it was me who initially agreed with the OP [original post], in a top-level comment, that Eliezer’s essay was essentially correct. You questioned that, and I have been defending my position… and now it’s somehow off-topic?

I don’t see where.

Certainty. A huge issue in early modern philosophy which has now been largely abandoned.

Completeness. Everything is either true or false, nothing is neither.

Consistency. Nothing is both true and false.

Convergence. Everyone can agree.

Objectivity: Everyone can agree on something that’s actually true

I dismissed it as an answer that fulfills all criteria, because it doesn’t fulfil Convergence. I didn’t use the word possible—you did in another context, but I couldn’t see what you meant. If nothing fulfils all criteria, then coherentism could be preferable to approaches with other flaws.

Because all of them individually can be achieved if you make trade offs.

Because things don’t stop being desireable when they are unavailable.

That isn’t at all clear.

Lowering the bar to whatever you can jump over ,AKA Texas sharpshooting,isn’t a particularly rational procedure. The absolute standard you are or are not hitting relates to what you can consistently claim on the object level: without the possibility convergence on objective truth, you can’t claim that people with other beliefs are irrational or wrong, (at least so long as they hit some targets).

It’s still important to make relative comparisons even if you can’t hit the absolute standard...but it’s also important to remember your relatively best theory is falling short of absolute standards.

Except for consistency, none of these seem actually desirable as requirements.

Certainty: Don’t need it, I’m fine with probabilities.

Completeness: I don’t need everything to be either true or false, I just need everything to have a justifiable probability.

Consistency: Agree.

Convergence+Objectivity: No Universally Compelling Arguments

That’s also Completeness.

Giving up on convergence has practical consequences. To be Consistent, you need to give up on the stance that your views are a slam dunk, and the other tribe’s views are indefensible.

I like particularism more than pragmatism, because all reasoning needs some kind of basis, but not all reasoning needs some kind of goal. For example, proving theorems in Peano arithmetic has a basis, but no goal.

More generally, I’d prefer not to ground philosophy in the notion that people follow goals, because so often we don’t. Life to me feels more like something spinning outward from its own basis, not toward something specific.

This approach seems wrongheaded to me, from the start. Perhaps I am misunderstanding something. But let’s take your example:

HALT! Proceed no further. Before even attempting to answer this question, ask: why the heck do you care? Why do you want to know the answer to this strange question, “what is a sandwich”? What do you plan to do with the answer?

In the absence of any purpose to that initial question, the rest of that entire section of the post is unmotivated. The sandwich alignment chart? Pointless and meaningless. Attempting to precisely define a “sandwich-like object”? Total waste of time. And so on.

On the other hand, if you do have a purpose in mind, then the right answer to “what is a sandwich” depends on that purpose. And the way you would judge whether you got the right answer or not, is by whether, having acquired said answer, you were then able to use the answer to accomplish that purpose.

Now, you could then ask: “Ah, but how do you know you accomplished your purpose? What if you’re a brain in a jar? What if an infinitely powerful demon deceived you?”, and so on. Well, one answer to that might be “friend, by all means contemplate these questions; I, in the meantime—having accomplished my chosen purpose—will be contemplating my massive pile of utility, while perched atop same”. But we needn’t go that far; Eliezer has already addressed the question of “recursive justification”.

It does not seem to me as if there remains anything left to say.

You’re right, in the end it’s best to say nothing, for then there are no problems. Alas, we suffer and strive and want things to be other than they already are, and so we say something and get ourselves into a world of trouble.

I’m not sure what your argument is here? Eliezer already wrote a post on this so no one should bother writing anything about the same topic ever again?

As best I can tell you are making an argument here for pragmatism but want to skip talking about epistemology. I won’t begrudge your right not to care about epistemology, only the point of this post was to explore a conundrum of epistemology, so I’m not quite sure what you’re trying to say here other than you agree with pragmatism about the problem of the criterion but don’t want to talk about epistemology.

(As a reminder, my policy of only replying to you once in a thread on my posts remains in place, although I remain open to reversing that decision.)

Eliezer already wrote a post on this, so no one should bother writing anything about the same topic that does not add anything new to Eliezer’s post, or do anything to result in changing one’s conclusion from that described in Eliezer’s post. This post does not (indeed, it would be quite difficult to write anything that does).

My point is precisely that conundrums of epistemology, and epistemological questions in general, are motivated by pragmatic things or else by nothing.

I do not think there is any “problem of the criterion”, except in a way such as is already addressed to the maximum possible degree of satisfaction by the linked Sequence post. Hence no “conundrum” exists.

When I said that nothing remains to say, I meant that anything else that’s said on this topic, over and above the linked post, is strictly superfluous—not that in general saying things is bad.

(Alright, breaking my own rule; we’ll see how it goes.)

I guess I don’t have much to say to this, as I disagree with your judgement here that there’s no value in saying the same things in a new way even if nothing new is added, although I also disagree of course that I don’t add anything. Sometimes saying the same thing in a different way clicks for someone when it didn’t click for someone else because not everyone has literally the same mind. Cf. Anna Salamon on learning soft skills and the project of distillation.

This is literally also one of my main points, so I guess we at least agree on something.

Sure, but I’m not satisfied with his post, hence I think there is more to say, though you obviously disagree.

Thus I’m left struggling to figure out a charitable motivation for your comments. That is, I’m not sure what point you are trying to make here other than you are annoyed I wrote something you didn’t want to read since I already agree with pragmatism, linked and highlighted your preferred Yudkowsky article on this topic, and we otherwise agree that there is something going on to be addressed regarding grounding problems.

It’s the dream of covering every topic with a minimum web of posts, that only grows, without overlap? (The dream of non-redundant scholarship)

Or SA doesn’t think ‘the problem of the criterion’ is motivated by a purpose (or SA’s purpose)?

writing something on a topic is quite different to solving it forever.

Yes. Though even if something is solved, it can be solved again in a different way.

They are motivated by whatever they are motivated by. It is possible for someone to value truth as a end in itself. Maybe you are not that person, but you have solved nothing for the people who value truth terminally

He’s one of those people. He hasn’t put forward a solution where he sticks only to doing things of measurable value. He insists that MWI is the correct interpretation of QM , and is so to a high degree of certitude. But an interpretation of QM cant be tested empirically, and has no empirical consequences So he needs a justification of epistemology that allows for a) high credibility about b) abstract topics of no practical significance. And he hasn’t got one, and he hasn’t solved epistemology for the wider rationalist community, because they also haven’t adopted pure pragmatism.

If there were already a satisfactory answer to the problem of the criterion , there would be no need to lower the bar by adopting pragmatism or instrumentalism. Solving epistemology for self confident epistemology is even harder.

Hello,

I would really appreciate it if you could write an entry relating the problem of the criterion in relation to whether or not someone can know a law, such as a criminal statute that prohibits some kind of behavior. I’m doing independent research (not for any university, but for myself—and not with the goal of a publication) on whether or not it is possible for someone to know a law. So far, I’ve managed to come across Tomoji Shogenji’s article “The Problem of the Criterion in Rule-Following,” whereby he posits that if the problem of the criterion is “insurmountable” as it appears to be, then no one can know a rule in order to follow it. The concept of a “law” may be related with the concept of a “rule,” whereby a lot of discussion about “rules” seems to come modernly from Wittgenstein. John Fisher also has an article entitled “Knowledge of Rules” in The Review of Metaphysics that I have not yet read that appears promising from the front material that I read on JSTOR.

I’ve read over your problem of the criterion article here a few times, and you start with the question of whether or not someone can know what a “sandwich” is.

It appears that you respond that it is not possible because there (1) are nebulous boundaries to be had and (2) “there is no true sandwich of which you can speak.”

Would you argue that the law is the same?

To me, it appears that there are many interpretations that can be had as to what a law means. An interpretation, in my opinion, is not the same as “knowledge” of a law. However, I don’t think legislators mean for there to be “nebulous boundaries” to a law and mean for there to be a “true law” of which they speak, namely a specific interpretation to be had that qualifies as having knowledge of the law. That does not necessarily mean (from what I infer) that there are not “nebulous boundaries” nor no true law of which legislators had the intent to be known.

Thank you in advance for reading.

I think it’s also the case that there are no true laws of which we can speak, but instead various interpretations of laws, though hopefully most people have agreeing interpretations, and much of the challenge within the legal profession is figuring out how to interpret laws.

Within common law (the only legal system I’m really familiar with), this issue of interpretation is actually a key aspect of the system. Judges serve the purpose of providing interpretations, and law is operationalized via decisions on cases that set precedents that can inform future interpretations, but ultimately it is the job of a judge to interpret both the law and the facts of the case to come to a decision. The intent of legislators is often considered, but ultimately it’s interpretation by judges that rules, not the rule writers.

My limited understanding is that other legal systems have similar features, but work differently (e.g. in sharia law my understanding is that lawyers do the interpreting rather than the judges).

This kind of pragmatism solves an easier version of the problem. Winning, and it’s close relative, prediction, can both be measured directly. That what allows you tell that something works without having an apriori theoretical justification. On the other hand, correspondence-to-reality can’t be tested directly...you can’t stand apart from the map territory relationship. In Scientism it’s common to assume that predctiveness is a sign of correspondence...

Coherentism may lack foundations in the sense that foundationalism has foundations, but it still has guiding principles—notably, that coherence is conducive to truth!

Right, and this gets at why Chisholm argues there are only really two positions—particularism and skepticism/nihilism—because coherentism still requires one know the idea of coherentism to start, although to be fair coherentism would theoretically allow one to stop believing in coherentism if believing in it ceased to be coherent!

How could believing in coherentism cease to be coherent?

For instance, if there is some self contradiction involved.

Chisholm can think what he likes, but what I am saying is that skepticism qua nihilism isn’t a viable position.

Right, I think Chisholm would agree that skepticism is not useful and you can’t do anything with it, so if we want to live he’d argue that particularism is, in fact, the only choice whether we like it or not.

Which is a problem if you have good reason to believe some things in general are true. If you do, you might as well believe whichever specific things are most plausible , even if they are not fully justified.

You have characterised scepticism as a nothing-is-true position. But “it is true that nothing is true” s self defeating. If the problem of the criterion means that nothing is well justified, then strong claims should be avoided , including strong negative claims like “nothing is true”. So scepticism done right is moderation in all things.

Correct; this is another way in which skepticism begs the question.

Right, the kind of “skepticism” I’m talking about here is different from everyday skepticism which is more like reserving judgement until one learns more. Skepticism here is meant to point to a position you might also call “nihilism”, but that’s not the term Chisholm uses and I stuck with his terminology around this.

I said it was self defeating which is a different problem.

I know it is different. The point is that it is better.

If we can prove that the Problem of the Criterion is a true problem, then the Problem of the Criterion is a false problem. Therefore, the Problem of the Criterion can never be proven to be a true problem.

Philosopher: “There is a way of thinking where you can never have a feeling of certainty. Not on any mental, physical, or social level. And I can teach it to you!”

Caveman: “Why would I want to learn that?”

Philosopher: ”...”

Perhaps one goal of the pragmatist is to avoid thinking about the Problem of the Criterion. It’s like “the Game” we used to play in grade school, where you lose the game by thinking about it. Kids would ambush each other by saying “you just lost the Game!” apropos of nothing.

If my take on this issue is wrong, I encourage proponents of the Problem of the Criterion to prove it!

This article and comment have used the word “true” so much that I’ve had that thing happen where when a word gets used too much it sort of loses all meaning and becomes a weird sequence of symbols or sounds. True. True true true. Truetrue true truetruetruetrue.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Semantic_satiation

Sounds like it’s time to become a caveman.

Rationalist: If it is impossible to be certain, I want to believe it is impossible to be certain.

What if it is impossible to believe the truth?

Reading this, my guess is that you underestimate the importance of being pragmatic to a single purpose.

When you are pragmatic, you are pragmatic with respect to some purpose. Let’s suppose that purpose is truth. You’ll get by quite fine in the world if you do that.

Yet, there’s some things you’ll miss out on. For example, suppose you want to know what it is like to be intentionally deceitful, perhaps because you are dealing with a person who lies and would like to understand what it is like to be them. To fully do that you have to think the same sort of thoughts a deceitful person would and that would require knowing, even if only temporarily, something not maximally predictive of the world to the best of your ability. Thus you must be able to think with the purpose of deceiving others about something in order to embody such thought long enough to get some first hand experience with thinking that way.

I think this generalizes to deeply understanding what it is like to be someone who isn’t you. In fact, I’ll go out on a limb and say the typical mind fallacy exists because we are especially bad at considering the problem of the criterion and thinking thoughts as if we were serving someone else’s purpose rather than our own.

I’m a fan of W. W. Bartley’s Pan Critical Rationalism, from his book The Retreat To Commitment. It doesn’t seem to me to fit in your list of approaches. Bartley was a student of Karl Popper, who proposed Critical Rationalism. CR, badly stated, says “This is the fundamental tenet: criticize all your beliefs and see what survives.” PCR cleans that up by saying “This is the best approach to epistemology we’ve discovered so far: criticize all your beliefs (including this one) and see what survives.”

Isn’t that better than believing in a foundational, unjustified criterion? Isn’t it more flexible than methodism? Isn’t it more useful than skepticism?

It seems like you still need some criterion through which to criticize your beliefs. Popper offers the criterion that “your past observations don’t falsify your theory”, and “your theory minimizes adhocness”, but by which criterion can you accept those criterion as true or useful?

Right! This is the slippery part about the problem of the criterion: literally any way you try to address it requires knowing something, specifically knowing the way you try to address it. It’s in this way that nearly every response to it could be argued to be a special case of particularism, since if nothing else you are claiming to know something about how to respond to the problem itself!

Bartley is very explicit that you stop claiming to “know” the right way. “This is my current best understanding. These are the reasons it seems to work well for distinguishing good beliefs from unhelpful ones. When I use these approaches to evaluate the current proposal, I find them to be lacking in the following way.”

If you want to argue that I’m using an inferior method, you can appeal to authority or cite scientific studies, or bully me, and I evaluate your argument. No faith, no commitment, no knowledge.

This comment describes a response that sounds exactly like pragmatism to me, so I’m not sure what the distinction you’re trying to make here is.

Also, as Matt already pointed out, you must have some criterion by which you criticize your beliefs else you literally could not make any distinction whatsoever, so then the problem just becomes one of addressing how to ground that, perhaps by accepting it on faith.

Trying to anticipate where the confusion between us is, it might help to say that taking something on faith need not mean it remain fixed forever. You can make some initial assumption to get started and then change your mind about it later (that’s fundamental to coherentist approaches).

See Matt’s comment, but CR and PCR sound like coherentist or methodist responses.

They sound not-foundationalist. But they differ in what they are replacing foundations with. Coherehence is quite different from attempted-refutation.

Laughs for eternity.

“Who is Descartes? Myth of the given? What are you talking about? I just want to define sandwiches.”