I’ve been watching French Top Chef (the best Top Chef, fight me) with my wife again, and I’m always impressed by how often the mentoring chefs, all with multiple michelin stars and years of experience, can just guess that a dish will work or that it will be missing something.

By far, whenever a chef points to an error (not a risk, an error), it’s then immediately validated experimentally: either the candidate corrected it and the jury comments positively on that aspect of the dish, or they refused to and failed because of that aspect of the dish.

Obviously, this incredible skill comes from years of cooking experience. But at its core, this is one of the fundamental idea of epistemology that experts and masters rediscover again and again in their field: static analysis.

The core intuition of static analysis is that when you write a computer program, you can check some things without even running it, just by looking at it and analyzing it.

What most programmers know best are type systems, which capture what can be done with different values in the program, and forbid incompatible operations (like adding a number and a string of characters together, or more advanced things like using memory that might already be deallocated).

But static analysis is far larger than that: it include verifying programs with proof assistants, model checking where you simulate many different possible situations without even running tests, abstract interpretation where you approximate the program so you can check key properties on them…

At its core, static analysis focuses on what can be checked rationally, intellectually, logically, without needing to dirty your hands in the real world. Which is precisely what the mentoring chefs are doing!

They’re leveraging their experience and knowledge to simulate the dish, and figure out if it runs into some known problems: lack of a given texture, preponderance of a taste, lack of complexity (for the advanced gastronomy recipes that Top Chef candidates need to invent)…

Another key intuition from static analysis which translates well to the Top Chef example is that it’s much easier to check for specific failure modes than to verify correctness. It’s easier to check that I’m not adding a number and a string than it is to check that I’m adding the right two number, say the price of the wedding venue and the price of the DJ.

It’s this aspect of static analysis, looking for the mistakes that you know (from experience or scholarship, which is at its best the distilled experience of others), which is such a key epistemological technique.

I opened with the Top Chef example, but almost any field of knowledge, engineering, art, is full of similar cases:

In Physics, there is notably dimensional analysis, which checks that two sides of an equation have the same unit, and order of magnitude estimates, which check that a computation is not ridiculously off.

In Chemistry, there is the balancing of chemical equations, in terms of atoms and electrons.

In Drug Testing, there are specific receptors that you know your compound should absolutely not bind with, or it will completely mess up the patient.

In most traditional field of engineering, you have simulations and back of the envelope checks that let’s you avoid the most egregious failures.

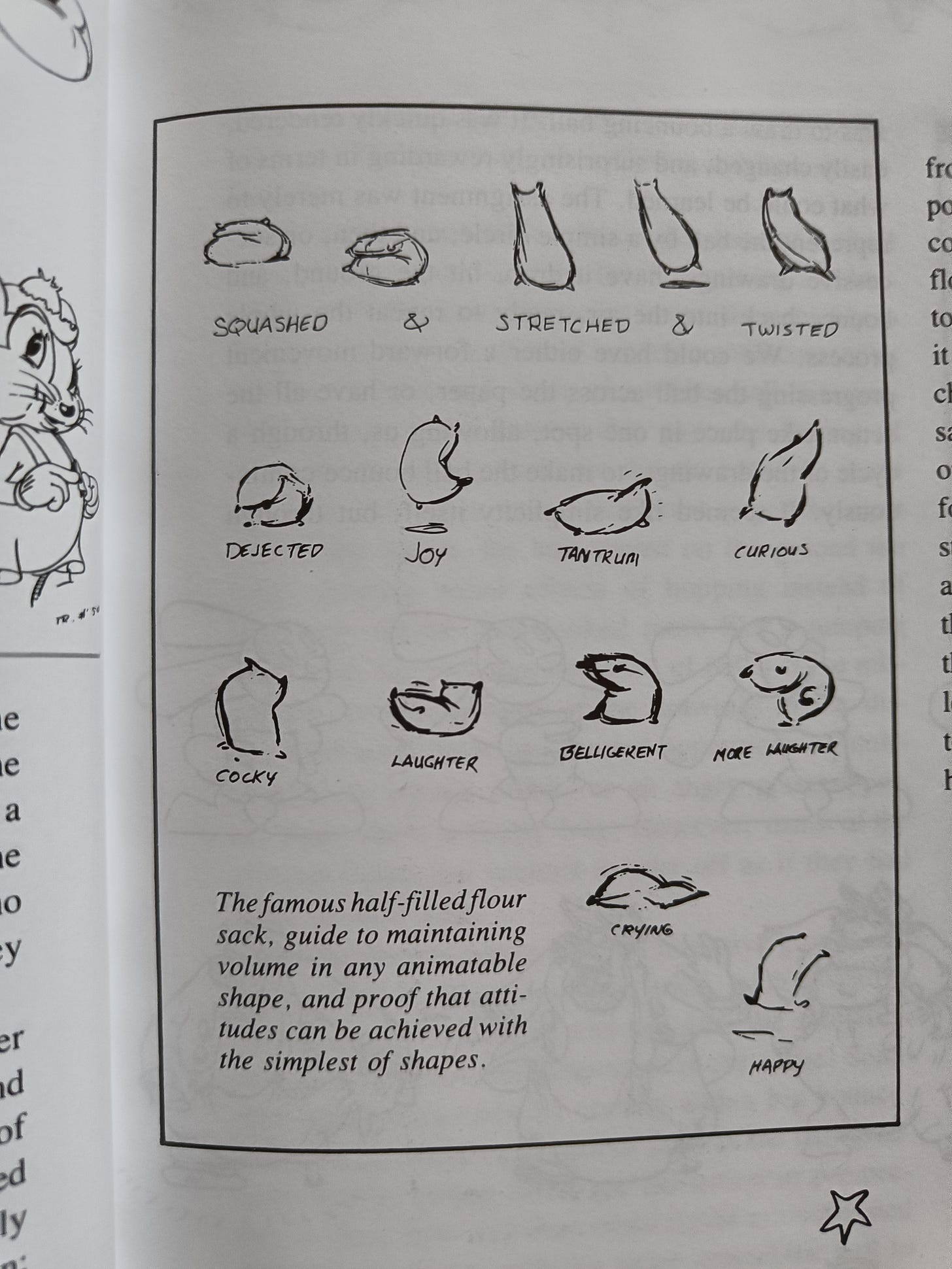

In Animation, the original Disney animators came up with the half-filled flour sack test to check that they hadn’t squashed and stretched their characters beyond recognition

From Disney Animation: The Illusion of Life

But there’s something even deeper about these checks: they are often incomplete.

In technical terms, a static analysis technique is complete if it accepts every correct program (and sound if it rejects all incorrect programs, but that’s not the main point here).

Of course, there are no truly complete techniques in practice. This is because restrictions are powerful: the more you constrain what you and others can do, the easier it is to reason about it, and check much more properties. So type systems often forbid programs that would actually run without runtime errors, but which are completely messed up to think about. That way, they can provide more guarantees.

And this is even truer in much fuzzier fields like art. Most of the rules in art are not actual perfect boundaries outside of which everything is wrong. They’re instead starting points, first approximations.

If you restrict yourself to perfect intervals, like traditional western music for hundreds of years, it’s safe to predict your piece of music will work decently well.

Progress then manifests itself by an epistemic exploration of this rule, a curious probing, looking for which parts can be skirted, bent, broken, while still reaching your end. This leads to things like Jazz, which breaks most of the harmonic and rhythmic code of western traditional music. And it’s great!

Which is why maybe the most exciting part of watching Top Chef are these moments of grace where the chefs and the jury doubt the intuition of the candidate, but the latter just go “Nah, I can get away with that.”, and realizes it so well that it explodes the previous rule.

That’s not to say that these rules are useless. Once again, the productive position is rarely in the false dichotomy between the absolute rule and the useless constraint, but in the perpetual interplay between making the world simpler so you can reason more about it before acting, and just trying things out to push your model of what can work.

Units / dimensional analysis in physics is really a kind of type system. I was very big into using that for error checking when I used to do physics and engineering calculations professionally. (Helps with self-documenting too.) I invented my own weird way to do it that would allow them to be used in places where actual proper types & type-checking systems weren’t supported—like most numerical calculation packages, or C, or Microsoft Excel, etc.

Yeah a case where this came up for me is angles (radians, degrees, steradians, etc.). If you treat radians as a “unit” subjected to dimensional analysis, you wind up needing to manually insert and remove the radian unit in a bunch of places, which is somewhat confusing and annoying. Sometimes I found it was a good tradeoff, other times not—I tended to treat angles as proper type-checked units only for telescope and camera design calculations, but not in other contexts like accelerometers or other things where angles were only incidentally involved.

Definitely!

Dimensional analysis was the first place this analogy jumped to me when reading Fly By Night Physics, because it truly used dimensions not only to check results, but also to infer the general shape of the answer (which is also something you can do in type systems, for example a function with a generic type a→a can only be populated by the identity function, because it cannot not do anything else than return its input).

Although in physics you need more tricks and feels to do it correctly. Like the derivation of the law of the pendulum just from dimensional analysis requires you to have the understanding of forces as accelerations to know that you can us g here.

Dimensions are also a perennial candidate for things that should be added to type systems, with people working quite hard at implementing it (just found this survey from 2018).

I looked at the repo, and was quite confused how you did it, until I read

That’s a really smart trick! I’m sure there are some super advanced cases where the units might cancel out wrongly, but in practice they shouldn’t, and this let’s you interface with all the random software that exists! (Modulo the run it twice, as you said, because the two runs correspond to two different drawings of the constants)

Another interesting thing with radiants is that when you write a literal expression, it will look quite different than in degrees (involving many more instances of π), so inspection can fix many errors without paying the full price of different types.

my package “is of somewhat limited use … semantic consistency is detected in a rather obscure way”, haters gonna hate 😂

Oh, I didn’t see it actually mentioned your package. 😂

I agree with the post generally. However, the chef example is (I think) somewhat flawed, as with all TV the footage is edited before you see it. So you have no idea how many pieces of advice the chef mentor gave that were edited out. In the UK version of the Apprentice the contestants would have a 3 hour planning session that would be edited down to 5 minutes, so you knew that whatever it was they were talking about in that 5 minutes of footage was the decision that would dominate their performance, meaning (as a viewer) it was very easy to see what was going to go wrong ahead of time.

You’re right but I like the chef example anyway. Even if cherry picked, it does get at a core truth—this kind of intuition evolves in every field. I love the stories of old hands intuitively seeing things a mile away.

I want to point out that one other big reason for static analysis being incomplete in practice is that it’s basically impossible to get completeness of static analysis for lots of IRL stuff, even in limited areas without huge discoveries in physics that would demand extraordinary evidence, and the best example of this is Rice’s theorem:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rice’s_theorem

Which is a huge limiter to how much we can perform static analysis IRL, though a more relevant result would probably be the Co-NP completeness result for Tautology problems, which again are related to static analysis.

Rice’s theorem or halting problem are completely irrelevant in practice as sources of difficulty. Take a look at the proofs. The program being analyzed would basically need to reason about the static analyzer, and then act contrary to the analyzer’s expectation. Programs you find in the real world don’t do that. Also they wouldn’t know (care about) the specific analyzer enough to anticipate its predictions.

Halting problem is a thing because there exists such an ornery program that makes a deliberate effort so that it can’t be predicted specifically by this analyzer. But it’s not something that happens on its own in the real world, not unless that program is intelligent and wants to make itself less vulnerable to analyzer’s insight.

The point is that it can get really, really hard for a static analyzer to be complete if you ask for enough generality in your static analyzer.

The proof basically works by showing that if you figured out a way to say, automatically find bugs in programs and making sure the program meets the specification, or figuring out whether a program actually is platonically implementing the square function infallibly, or any other program that identifies non-trivial, semantic properties, we could convert it into a program that solves the halting problem, and thus the program must be at least be able to solve all recursively enumerable problems.

For a more in practice example of static analysis being hard, I’d say a lot of NP and Co-NP completeness results of lots of problems, or even PSPACE-completeness for problems like model checking show that unless huge assumptions are made about physics, completeness of static analysis is a pipe dream for even limited areas.

Static analysis will likely be very hard for a long time to come.

My objection is to “IRL” and “in practice” in your top level comment, as if this is what static analysis is actually concerned with. In various formal questions, halting problem is a big deal, and I expect the same shape to be important in decision theory of the future (which might be an invention that humans will be too late to be first to develop). Being cooperative about loops of mutual prediction seems crucial for (acausal) coordination, the halting problem just observes that the same ingredients can be used to destroy all possibility of coordination.

I did a lightning talk at PyCon demoing a personal project for doing static analysis on anything that can be represented as text, such as playlists and clothing: https://youtu.be/xQ0-aSmn9ZA?t=871