My intellectual journey to (dis)solve the hard problem of consciousness

Epistemological status: At least a fun journey. I wanted to post this on April Fool’s Day but failed to deliver on time. Although April Fool’s Day would have been lovely just for the meme, this is my best guess after thinking about this problem for seven years.

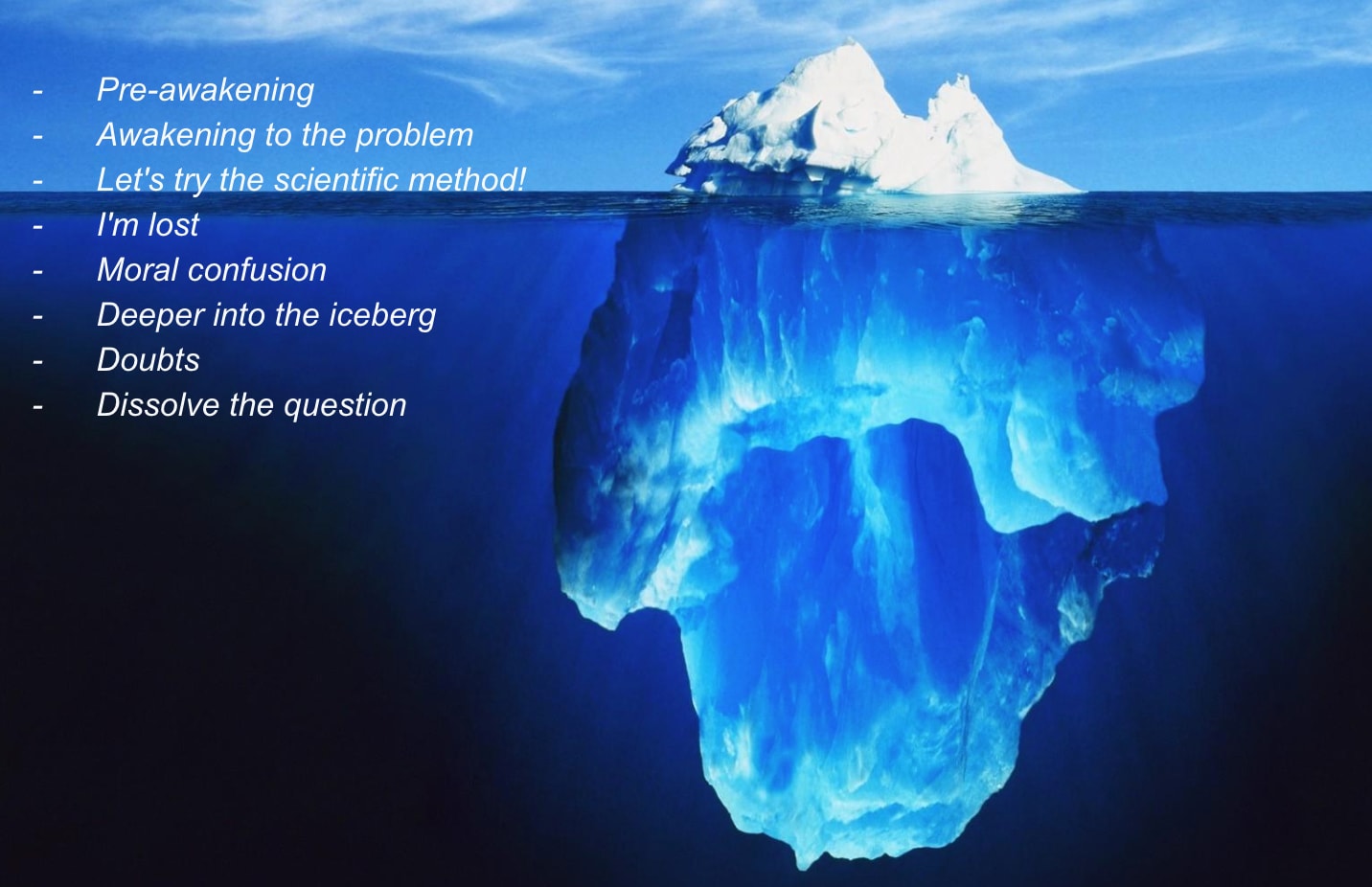

I invite you to dive deep into the consciousness iceberg with me. The story will be presented chapter by chapter, presenting you with the circulating ideas I’ve absorbed, building ideas in your brain to deconstruct them better until I present you with my current position. Theoretically, this should be easy to follow; this post has already been beta-tested.

We’ll go through a pre-awakening phase, during which I was unfamiliar with the theory of mind literature, then an awakening to the problem of consciousness, followed by a presentation of some essential elements of the scientific literature on consciousness, and finally, a phase of profound confusion before resolving the problem. The chronology has been slightly adapted for pedagogical purposes.

Why do I think this is important? Because I think more and more people will be confused by this notion as AI progresses, I believe it is necessary to be deconfused by it to have a good model for the future. I think one of the main differences in worldview between LeCun and me is that he is deeply confused about notions like what is true “understanding,” what is “situational awareness,” and what is “reasoning,” and this might be a catastrophic error. I think the tools I give in this blog post are the same ones that make me less confused about these other important notions.

Theoretically, at the end of the post, you will no longer ask “Is GPT-4 conscious or not?” by frowning your eyebrows.

Oh, and also, there is a solution to meta-ethics in the addendum.

If you’re already an Eliminativist, you can skip right to Chapter 7, otherwise, well, you’ll have to bear with me for a while.

Chapter 1: Pre-awakening, before stumbling upon the hard problem

In high school, I was a good student; in philosophy class, I was just reciting my knowledge to get good grades. We discovered Freud’s framework on the conscious/preconscious/unconscious. At the time, I heard people say that consciousness was mysterious, and I repeated that consciousness was mysterious myself. Still, I hadn’t really internalized the difficulty of the problem.

As a good scientist, I was trying to understand the world and had the impression that we could understand everything based on the laws of physics. In particular, I thought that consciousness was simply an emergent phenomenon: in other words, atoms form molecules that form organs, including the brain, and the brain gives rise to various behaviors, and that’s what we call consciousness.

Cool, it’s not so mysterious!

In the end, it’s not that complicated, and I told myself that even if we didn’t know all the details of how the brain works, Science would fill in the gaps as we went along.

Unfortunately, I learned that using the word emergent is not a good scientific practice. In particular, the article “The Futility of Emergence” by Yudkowsky convinced me that the word emergence should be avoided most of the time. Using the word emergence doesn’t make it possible to say what is conscious and what is not conscious because, in a certain sense, almost everything is emergent. To say that consciousness is emergent, therefore, doesn’t make it possible to say what is or what is not emergent, and thus isn’t a very good scientific theory. (Charbel2024 now thinks that using the word ‘emergence’ to point toward a fuzzy part of the map that tries to link two different phenomena is perfectly Okay).

So we’ve just seen that I’ve gradually become convinced that consciousness can’t be characterized solely as an emergent phenomenon. I’ve become increasingly aware that consciousness is a fundamental phenomenon. For example, when you hear Descartes saying, “I think therefore I am,” my interpretation of his quote is that consciousness is sort of “the basis of our knowledge,” so it’s extremely important to understand this phenomenon better.

Consciousness is becoming very important to me, and I have a burning desire to understand it better.

Chapter 2: Awakening to the problem

In this chapter, I’ll explain how I gradually became familiar with the literature on the philosophy of mind, which deals with the problem of consciousness.

Consciousness became increasingly important to me, and I started reading extensively. I stumbled upon a thorny mystery: how are the brain’s physiological processes responsible for subjective experiences such as color, pain, and thought? How does the brain produce thoughts from simple arrangements of atoms and molecules?

This is the HARD PROBLEM of consciousness, which describes the challenge of understanding why and how subjective mental states emerge from physical processes. Despite numerous advances in neuroscience, this problem remains unsolved.

The Hard problem? Wow, I’m really interested in this. It’s the problem I need to work on, and I’m a bit more delving into philosophical literature.

In philosophy, there are two main types of consciousness:

Access Consciousness:

It is the process by which information in our mind is accessible in cognitive operations, such as retrieving information from short-term or long-term memory.

It is often considered more easily observable, as we can track the transfer of information from one brain area to another.

Phenomenal Consciousness:

Subjective experience is often referred to as qualia.

“What it is like to be conscious.”

It is considered more challenging to explain and scientifically study because it is inherently subjective.

Here is a “metaphysically and epistemically innocent” definition from Schwitzgebel (2016):

Phenomenal consciousness can be conceptualized innocently enough that its existence should be accepted even by philosophers who wish to avoid dubious epistemic and metaphysical commitments such as dualism, infallibilism, privacy, inexplicability, or intrinsic simplicity. Definition by example allows us this innocence. Positive examples include sensory experiences, imagery experiences, vivid emotions, and dreams. Negative examples include growth hormone release, dispositional knowledge, standing intentions, and sensory reactivity to masked visual displays. Phenomenal consciousness is the most folk psychologically obvious thing or feature that the positive examples possess and that the negative examples lack.

At that time, I did not know that the very existence of the hard problem was debated in philosophy.

When I encountered this hard problem, I was a computer scientist. So, I was trying to imagine how to “code” every phenomenon, particularly consciousness. I wondered what lines of code were needed to code consciousness. I was a functionalist: I thought we could explain everything in terms of functions or structures that could be implemented on a computer. Not for long.

Functionalism and the potential to replicate the consciousness or functions of a brain within a computer yield surprising outcomes. Computers and Turing machines are not restricted to a single physical substrate. These Turing machines can be realized via a multitude of different media. Various substrates, such as brain tissue, silicon, or other materials, can implement complex functions.

As an example of a Turing machine, we could imagine people holding hands. So we could imagine simulating the functioning of the brain’s 100 billion neurons by 100 billion people simulating the neurons’ electrical stimulation by holding hands.

This hand-holding system would then be conscious? WTF

The functionalism philosophy seemed to imply things that were too counterintuitive.

There, I discovered the philosopher David Chalmers, who rigorously defended the hard problem.

Chalmers fanboy: This is my man. The hard problem is real. Nice style btw | Chalmer tells us that there is a gap, an explanatory gap, between physical and mental properties. |

The explanatory gap in the philosophy of mind, represented by the cross above, is the difficulty that physicalist theories seem to have in explaining how physical properties can give rise to a feeling, such as the perception of color or pain.

For example, I can say: “Pain is the triggering of type C fibers,” which is valid in a physiological sense, but it doesn’t help us understand “what it feels like” to feel pain.

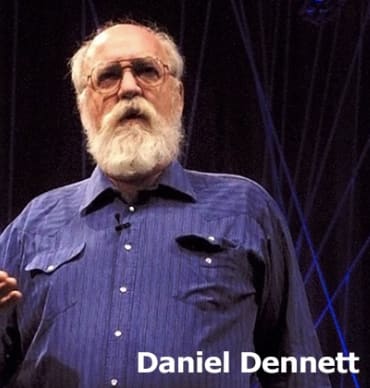

I also met Daniel Dennett.

He impresses me with his ability to discuss many subjects. Unfortunately, even though he’s relevant to many subjects, I had the impression that everything he said about consciousness was either trivial or wrong and that he was dodging the issue of the hard problem.

Dennett & eliminativists: Wow, this man is spot on everything, but everything he says about consciousness is either trivial or wrong; nice beard btw | For him, there are no mental properties to explain. |

For him, there are no mental properties to explain. We call this “Eliminativism”: he wants to eliminate the concept of qualia; there is no hard problem. Science can explain consciousness, and he’s a physicalist, i.e., he thinks everything can be explained in terms of physical properties.

Dennett does not convince me. It seemed to me he was just repeating: “What do you mean by qualia?” and he was just plainly ignoring the problem. I was paying attention to what he was saying, but what he was saying was very alien to me.

It doesn’t satisfy me at all.

The more I think about it, the more I think this is a crucial subject. If AIs were conscious, it would be the craziest thing in history.

Chapter 3: Let’s try the scientific method!

Okay, okay. I will introduce you to three methods: Global Workspace Theory (GWT), integrated information theory (IIT), and the list of criteria method.

But before that, I also thought that becoming an expert in Artificial Intelligence would help me better understand consciousness. Done. Unfortunately, I didn’t learn anything about consciousness.

Global Workspace Theory

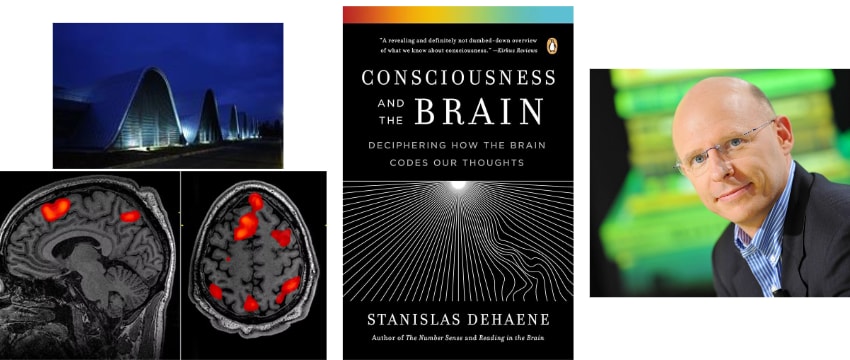

After my Master 2, I interned at Neurospin, a laboratory for studying the brain south of Paris. The lab is led by Stanislas Dehaene, one of the founding fathers of Global Workspace Theory and the author of “Consciousness and the Brain.”

At first, I was pretty unimpressed by Cognitive Science, and I said stuff like, “EEG or fMRI statistics are a dead end, a bit like trying to read the stains in coffee grounds or understanding computers by analyzing the Fourier spectrum of the ventilator noise…”

Until I saw the following experiment:

Masking is an experiment used in the laboratory to make numbers, letters, and objects disappear from consciousness. You stare at the screen, and a number appears, followed by a mask. Then, you try to name the number to identify it.

The number will appear for 300 milliseconds:

You probably don’t have any difficulty to spot the 9.

….

…

Ok, now let’s try with 33 milliseconds:

Most of you should no longer be able to see the figure.

It’s even hard to believe that there’s still a number. But I swear to you, there’s still a number;[1] the number appears on your retina but is no longer in your consciousness.

To sum up:

if the duration of the number’s appearance is short, the signal is subliminal

if the duration of the signal is long, the signal is conscious

Question: where does the signal go? Why does it fade before consciousness?

All these experiments allow us to measure access consciousness in adults using the reportability criterion. The reportability criterion means being able to say, “I saw the number” (other criteria are used in babies and animals).

We can then measure the Neural Correlates of Consciousness, which constitute the smallest set of events and neural structures that activate in a highly correlated way with the subject’s report.

What happens is that the visual signal reaches zones V1 and V2 at the back of the brain, and then there are two possibilities:

Either the signal is not of sufficient duration, and the signal fades away (left).

Or, if the signal is sufficiently strong and of sufficient duration to reach the cortex and activate the pyramidal neurons (which have very long connections linking different, distant parts of the brain), then boom! It’s the ignition 🚀! The information is now accessible to all cerebral areas (right).

Those two regimes are clearly distinct, according to Dehaene.

These phenomena have been systematized in what is known as the “Global Workspace Theory,” which partly explains how information circulates in the brain: Information is transmitted from the visual area to the language area, and we find back the reportability criterion!

Incredible! We can now understand some conditions for humans to say, “I saw the signal!”.

So that’s it. Problem solved, isn’t it? ✓

Nah, I’m still unhappy: this solves the problem of access consciousness but not phenomenal consciousness.

Moreover, when I looked at the lines of code in Dehaene’s simulations of the global workspace, I couldn’t convince myself that this code exhibited consciousness: He built a simulation, but his simulation is clearly not conscious. Besides, the Global Workspace Theory is just one theory among many, and there are plenty of others.

So, I continued my quest for theories of consciousness.

Integrated Information Theory

Why not try to formalize consciousness mathematically?

This is what integrated information theory proposes: we can start from 5 axioms based on our phenomenal experience and try to define a metric, a score of consciousness.

According to IIT, for a system to be conscious, it must be capable of integrating information under specific properties. Consciousness is the intrinsic capacity of a neural network to influence itself, determined by the maximum level of integrated information admitted by this network.

Each of these axioms measures a property of graphs, which are mathematical objects made up of a set of nodes and edges connecting the nodes. For example, we have eight nodes above.

On the left, the graph is complete: each node is connected to 7 other nodes.

On the right, the graph comprises 4 unconnected parts, so it is not very integrated, and the system will have a correspondingly small Phi.

Phi is a number that sums up the five properties. You could say that it’s like multiplying the score of the five properties, and you get a number:

Then we can imagine something like the following graph:

On the x-axis, different objects, such as a computer and a brain, that can be converted into the formalism of a graph. For each of these graphs, we can calculate a Phi. But now, since we have a continuous metric, they need to define a threshold between what is conscious and what is not conscious. | |

But this threshold-setting operation is mathematically super ugly and arbitrary. But on the other hand, if you don’t set a threshold, everything is a bit conscious. For example… even a carrot would be minimally conscious. WTF |

IIT ad hoc statistics: Hum, interesting axiomatic, but doesn’t this imply panpsychism??

My understanding of the problem is that if we take this axiomatic, everything becomes at least minimally conscious, and that’s where we can sink into panpsychism.

Another problem with this theory is that it bites its own tail: IIT uses a mathematical formalism, the graph formalism, but it’s not easy to construct graphs from observations of the universe and to say what is information processing and what does not seem to depend on an observer.

For example: is the glass on my table an information processing system? No? However, glass is a band-pass filter for visible light and filters out ultraviolet light. Does that mean that the glass is minimally conscious?

The list of criteria method

Okay, we’ve seen GWT and IIT. I’d like to talk about one last method, which I call the list of criteria method.

For example, in the above image, you have a list of criteria for the perception of suffering, and in particular, in animals, we can study the criteria that allow us to know whether animals feel pain or not.

That’s the best method Science has been able to give us.

But even if this is the method used for animals, I didn’t find it satisfactory, and I have the impression that it still doesn’t solve the hard problem: lists are not elegant, and even if this is the SOTA method for pain assessment for animals, none of the items in the above list seemed to explain “what it’s like to feel suffering.”

Chapter 4: I’m lost

It’s time to introduce an important concept: Philosophical Zombie.

The term philosophical zombie refers to a being that is physically and outwardly indistinguishable from a conscious being, both in behavior and in physical constitution, but which nevertheless has no awareness of its own existence or the world, no personal feelings or experiences.”

Although they behave as if they were experiencing emotions, zombies do not feel any, even though the biological and physical processes that determine their behavior are those of a person experiencing emotions.

To fully understand the philosophical zombie, we also need to introduce another notion: epiphenomenalism.

In the context of the philosophy of mind, epiphenomenalism is the thesis that mental phenomena (beliefs, desires, emotions, or intentions) have no causal power and, therefore, produce no effect on the body or on other mental phenomena [2].

For example, we can see that a physical state, P1, leads to a mental state, M1, and the physical state leads to a new physical state, P2, but mental states have no influence on the physical world.

We’re going to make a practical study of all this in a play:

[Pro Tip—I’ve presented this post during a talk, and during the presentation, I asked people to play different roles, and this was pretty effective in waking them up!]

From Zombies: The Movie — LessWrong :

FADE IN around a serious-looking group of uniformed military officers. At the head of the table, a senior, heavy-set man, GENERAL FRED, speaks.

GENERAL FRED: The reports are confirmed. New York has been overrun… by zombies.

COLONEL TODD: Again? But we just had a zombie invasion 28 days ago!

GENERAL FRED: These zombies… are different. They’re… philosophical zombies.

CAPTAIN MUDD: Are they filled with rage, causing them to bite people?

COLONEL TODD: Do they lose all capacity for reason?

GENERAL FRED: No. They behave… exactly like we do… except that they’re not conscious.

(Silence grips the table.)

COLONEL TODD: Dear God.

GENERAL FRED moves over to a computerized display.

GENERAL FRED: This is New York City, two weeks ago.

The display shows crowds bustling through the streets, people eating in restaurants, a garbage truck hauling away trash.

GENERAL FRED: This… is New York City… now.

The display changes, showing a crowded subway train, a group of students laughing in a park, and a couple holding hands in the sunlight.

COLONEL TODD: It’s worse than I imagined.

CAPTAIN MUDD: How can you tell, exactly?

COLONEL TODD: I’ve never seen anything so brutally ordinary.

A lab-coated SCIENTIST stands up at the foot of the table.

SCIENTIST: The zombie disease eliminates consciousness without changing the brain in any way. We’ve been trying to understand how the disease is transmitted. Our conclusion is that, since the disease attacks dual properties of ordinary matter, it must, itself, operate outside our universe. We’re dealing with an epiphenomenal virus.

GENERAL FRED: Are you sure?

SCIENTIST: As sure as we can be in the total absence of evidence.

GENERAL FRED: All right. Compile a report on every epiphenomenon ever observed. What, where, and who. I want a list of everything that hasn’t happened in the last fifty years.

CAPTAIN MUDD: If the virus is epiphenomenal, how do we know it exists?

SCIENTIST: The same way we know we’re conscious.

CAPTAIN MUDD: Oh, okay.

GENERAL FRED: Have the doctors made any progress on finding an epiphenomenal cure?

SCIENTIST: They’ve tried every placebo in the book. No dice. Everything they do has an effect.

[...]

Great! This text by Yudkowsky has convinced me that the Philosophical Zombie thought experiment leads only to epiphenomenalism and must be avoided at all costs.

Did I become a materialist after that? No.

I could not be totally “deconfused” about consciousness, why? Mainly because of the following paper by Eric Schwitzgebel:

If Materialism Is True, the United States Is Probably Conscious

Eric Schwitzgebel

Philosophical Studies (2015) 172, 1697-1721

From the abstract: “If we set aside our morphological prejudices against spatially distributed group entities, we can see that the United States has all the types of properties that materialists tend to regard as characteristic of conscious beings.”

So what Eric Schwitzgebel does in this paper is that he lists many properties that materialists say are necessary for consciousness. And he tells us, OK, look at the US that seems to have all the properties that you say are important for consciousness. So, in the end, wouldn’t the United States also be conscious if you put aside your bias against entities that are spatially distributed?

And I must say that the paper is convincing. It really gave me a lot of doubts.

Ultimately, I am left without a coherent position on the nature of consciousness. The more I explore the philosophical arguments and thought experiments, the more I find myself questioning the foundations of both materialist and non-materialist theories. It seems that each approach, when pushed to its logical limits, leads to conclusions that are difficult to accept. This leaves me in a state of philosophical deep uncertainty.

After a while, I even went mad because I couldn’t explain consciousness. I see it in myself, but I can’t explain it in any way. Maybe the only consciousness in the universe is mine, and that’s when I came across the wonderful philosophy of solipsism.

I also began to devour podcasts and interviews, each more contradictory than the last. I particularly enjoyed Robert Lawrence Kuhn’s channel, which interviews different philosophers with radically different views in the same episode.

Chapter 5: Moral Helpnesness

Here, I’d like to take a little detour into morality before the resolution.

It seems to me that consciousness is an important criterion for defining moral agents (in particular, valence, the ability to feel pain and pleasure, two dimensions of consciousness). (Yes, I was an essentialist in this regard)

After a while, I said to myself that we don’t understand anything about consciousness. Perhaps consciousness is not at all correlated to intelligence. Indeed, cows and fish are less intelligent than humans in many respects, but they have the fundamental ability to feel suffering, and it’s hard to say for sure that ‘there is nothing it is like to be a fish.’ So, let’s go for it; let’s become vegan.

That’s when I came across Brian Tomasik’s blog, which explains that we should “minimize walking on the grass” to minimize insect suffering. And I’ve also stumbled upon the People for the Ethical Treatment of Reinforcement Learners. Promoting moral consideration for simple reinforcement learning algorithms. Then I also sympathized with Blake Lemoine, that Google engineer who said that language models are conscious, and I didn’t feel much further ahead than he did.

Google’s Lambda Polemic: I feel you, my friend; this is not a simple topic

I was maximally confused.

But I continued my research. In particular, I discovered the Qualia Research Institute, which was trying to better understand consciousness through meditation and the study of psychedelic states. I thought that their Qualia formalism was the only path forward. And I was not convinced by everything, but at least this view seemed coherent.

I knew most people on Lesswrong and Yudkowsky were eliminativists, but I was not able to fully understand/feel this position.

What? Yudkowsky thinks animals who are not able to pass the mirror test are not really conscious? He thinks babies are not conscious? He thinks he’s not always conscious?? The mind projection fallacy is stronger than I thought.[3]

Chapter 6: Doubts

I’ve discussed the hard problem with a lot of people, and a lot of them were not familiar with it at all. Worse, they were not even able to understand it. Either I’m the only one conscious, either they are not phenomenally conscious, or they are not sufficiently intelligent to understand my pointer (or maybe I was explaining it badly?).

Or maybe the hard problem only exists in my head; is it an illusion or a wrong framing?

I began to doubt the existence of this hard problem

…

I’ve heard many people say, “The notion of consciousness will one day be deconstructed in the same way as we deconstructed the notion of Life.”

Indeed, there’s no single property that defines Life; it’s rather a list of properties: reproduction and evolution, survival, and remaining in a state of good working order, but no property is sufficient in itself.

I wasn’t convinced, but I said to myself, “OK, why not? Let’s see what happens if we say that consciousness is a list of properties.” I was a little disappointed because I don’t find this method very elegant, but hey, let’s give it a try.

This was a necessary leap of faith.

…

In addition, I began to take Yudkowsky’s article from Philosophical Zombies earlier more seriously. In particular, I wondered whether his text couldn’t be applied to the hard problem.

Take a look at the above image, which sums up the different theories of consciousness.

You may be familiar with the Anna Karenina principle: “All happy families are alike, but each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” Well, I thought it’s a bit the same with theories of consciousness: when we say: “Yo, the hard problem of consciousness exists,” and then we try to patch this problem, it brings up lots of very complicated and different theories, whereas if we say: “there’s no hard problem”, well, it’s much simpler.

many of them shared my concerns, almost precisely, but my own ideas from other lips sounded obsessive and ill-conceived.

Greg Egan, Learning to Be Me

…

Another piece of the puzzle is the blog post by Andrew Critch: Consciousness as a conflationnary alliance term. In summary, consciousness is a very loaded/bloated/fuzzy word, people don’t mean the same thing when talking about it.

Here’s a list of possible definitions encountered by Critch when asking people:

(n≈3) Consciousness as introspection. Parts of my mind are able to look at other parts of my mind and think about them. That process is consciousness. Not all beings have this, but I do, and I consider it valuable.

Note: people with this answer tended to have shorter conversations with me than the others, because the idea was simpler to explain than most of the other answers.(n≈3) Consciousness as purposefulness. There is a sense that one’s life has meaning, or purpose, and that the pursuit of that purpose is self-evidently valuable. Consciousness is a deep the experience of that self-evident value, or what religions might call the experience of having a soul. This is consciousness. Probably not all beings have this, and maybe not even all people, but I definitely do, and I consider it valuable.

(n≈2) Consciousness as experiential coherence. I have a subjective sense that my experience at any moment is a coherent whole, where each part is related or connectable to every other part. This integration of experience into a coherent whole is consciousness.

…

So maybe consciousness has always been a linguistic debate?

Or you can make a whole list of criteria!

For example, here’s a list of some theoretical properties. We’ve just seen GWT and IIT, but there are plenty of others:

There are also behavioral properties of progressive abstraction: from the low-level features like basic sensation or vibrotactile sensations to more and more abstract features like memory, intentionality, and imagination, and finally, fairly high-level features like language, meta-cognition, introspection, theory of mind, etc… This is like stacking cognition bricks:

The great thing about lists is that you can zoom in on an item, and if you look at one of these properties in isolation, it’s no longer mysterious. You can reimplement each of these properties with AIs.

For example, let’s take meta-cognition. The paper “LLMs mostly know what they know” shows that LLMs have some metacognition; they know what they know, and it’s possible to train models to predict the probability that they know the answer to a question.

As a result, I didn’t think that metacognition was mysterious anymore.

And this is not just for metacognition: I think you can reimplement/understand all the other items in the preceding lists.

Here we are.

Chapter 7: Eureka!

Chapter 7: Eureka: The hard problem is a virus! And some people don’t have the virus :)

At parties, I was a super propagator of a virus that made people waste a lot of time on this problem.

The Meta problem

[if this subpart doesn’t click, don’t stop, just continue to the next subsection]

To explain this virus, I suggest we consider the metaproblem of consciousness. The meta-problem consists of explaining why we think consciousness is a difficult problem.

Nate Soares has given some answers to this problem and a large part of the ‘distilled’ solution is contained in this comment:

“[...]. Don’t start by asking ‘what is consciousness’ or ‘what are qualia’; start by asking ‘what are the cognitive causes of people talking about consciousness and qualia’, because while abstractions like ‘consciousness’ and ‘qualia’ might turn out to be labels for our own confusions, the words people emit about them are physical observations that won’t disappear. Once one has figured out what is going on, they can plausibly rescue the notions of ‘qualia’ and ‘consciousness’, though their concepts might look fundamentally different, just as a physicist’s concept of ‘heat’ may differ from that of a layperson. Having done this exercise at least in part, I [...] assert that consciousness/qualia can be more-or-less rescued, and that there is a long list of things an algorithm has to do to ‘be conscious’ / ‘have qualia’ in the rescued sense. The mirror test seems to me like a decent proxy for at least one item on that list (and the presence of one might correlate with a handful of others, especially among animals with similar architectures to ours). [...] ”

The quest to unravel the mystery of consciousness involves not just defining the term but reconstructing the entire causal chain that leads some people to speak about it, why we utter the word “con-scious-ness”—to understand why, for example, my lips articulate this word.

If we can fully map this causal chain, we can then anticipate the circumstances in which people discuss “consciousness”. The various aspects of consciousness, enumerated in the lists seen earlier, are each useful concepts along this causal path.

By untangling this complexity, it becomes possible to redefine the notions of “qualia” and “consciousness”. It’s a bit like the term “heat”, which is perceived differently by a physicist and a non-specialist. Nate continues:

“[...] The type of knowledge I claim to have, is knowledge of (at least many components of) a cognitive algorithm that looks to me like it codes for consciousness, in the sense that if you were to execute it then it would claim to have qualia for transparent reasons and for the same reasons that humans do, and to be correct about that claim in the same way that we are. From this epistemic vantage point, I can indeed see clearly that consciousness is not much intertwined with predictive processing, nor with the “binding problem”, etc. I have not named the long list of components that I have compiled, and you, who lack such a list, may well not be able to tell what consciousness is or isn’t intertwined with. However, you can still perhaps understand what it would feel like to believe you can see (at least a good part of) such an algorithm, and perhaps this will help you understand my confidence. Many things look a lot more certain, and a lot less confusing, once you begin to see how to program them.”

The creation of a list of criteria is a crucial step; the list must be sufficiently elaborate to explain, among other things, why philosophers articulate with their lips the word “con-scious-ness” and pronounce syllable by syllable the expression “hard-pro-blem”.

I would argue that the lists seen above are good summaries of what consciousness corresponds to under the prism of the meta-problem.

Clustering is hard

Maybe becoming an expert in ML was not entirely for nothing.

There is an important algorithm in machine learning called the clustering algorithm. We give the algorithm the position on the x and y axis of all the points, and then the algorithm will say, “Okay, we have three clusters here, or two clusters, or one cluster, or lots of clusters.” That’s the clustering algorithm.

Sometimes, it is easy to determine the different clusters. For example, in the above image, there are clearly three clusters.

But sometimes it is much more difficult:

Clustering depends on an algorithm, and this algorithm is completely arbitrary. There is no single algorithm that solves all clustering problems. It’s really a problem that is not solved in machine learning and that won’t be solved, and there is no unique solution to this problem in full generality.

In the above image, clustering is going to be completely arbitrary.

Once we have done this work, we say that there is a cluster here, a cluster here, a cluster here, and we can give them names. For example, I can say, “Ah, the cluster that is in the top right, I will say that it is the north cluster.” I can give names, and labels to these different clusters. This is how human beings have evolved language: “All these things are trees, all these things are reflexes. All these things are chairs. All these things are memory. All these things are consciousness”. We can give names to things, but ultimately, intrinsically, what happens is that we see different phenomena, and we cluster them in the brain. Different neurons will react to different clusters, and we will have a neuron that will be associated with each cluster.

So here, I’m showing you a little bit different clustering algorithms. We have different clouds of points and different clustering algorithms, and different clustering algorithms will not necessarily give the same answers.

For example, in one column, we have the Bob algorithm, and in another column, the Alice algorithm, each of the individuals, each of the people in the street that Andrew Critch interviewed earlier.

For consciousness, we have this pyramid of capacities:

We have different points here, and then we have to cluster these capacities and name them.

There are people who will say, “Okay, consciousness is just that,” and they will make a circle on the top of the pyramid, or they will say, “That’s consciousness!” and they will draw a giant circle. Then, there are people who will say, “No, what interests me more is sentience.” They will say, “Okay, we will make a circle here in the bottom, near the basic somatosensory stuff,” and they will say that’s sentience.

The problem is completely ill-defined.

So, people will see the same capacities and name things differently. But you see that the problem is not very well posed. Finally, what matters more is what the territory looks like, and what the different capacities that are underlying look like.

Interpretability

This is an image that I really like. An image that was found by Chris Olah when he studied the circuits in image recognition neural networks. What his team found is that the car neuron is connected to three neurons that are lower level than the car neuron. For this image classifier, a car is actually a window, a body, and wheels that are each, respectively, at the top, middle, and bottom, and when the three neurons are activated, the car neuron is activated. That’s how neural networks work for vision. (Obviously, this is a simplification).

Why am I talking about this kind of thing?

Well, obviously, because your brain is also a neural network, there are also neurons, and so there is an algorithm that allows us to say whether something is conscious or not.

And maybe your algorithm is, “Okay, there is memory, language, or reasoning, and boom, this is consciousness”. Or maybe it’s an algorithm that is totally different; for example, when you hurt a dog, it has a reflex, and so, here, you can substitute reasoning for reflex, etc. And that gives you another notion of consciousness. But in the end, what happened is that during your learning, you saw the word consciousness associated with different things. And then, what happened in your brain is that these different things, that appeared next to the word consciousness assembled with each other. This assembly is different from one person to another, and that’s why, then, different people will associate the consciousness neuron with different properties.

And at the end of the day, I don’t think there is much difference between the problem of consciousness and the sorites paradox:

And what I’m saying here applies to the word consciousness, it applies to the word sentience, it applies to a lot of other things.

The ghost argument

Imagine a child who believes that ghosts haunt his house every night before he goes to sleep, even though he’s old enough to understand rationally that ghosts don’t exist. Although he knows that everything can be explained without resorting to the idea of ghosts, he nevertheless feels their presence. It could be said that a specific neuron in his brain is intensely activated, associated with the notion of a ghost when he experiences fear. As he grows older, the child gradually begins to convince himself that ghosts don’t exist, adopting a more rational approach to the world. Gradually, the “ghost neuron” ceases to be stimulated and begins synaptic pruning, and this natural process gradually weakens and eliminates the synaptic connections associated with his fear of ghosts.

This is similar to the hard problem of consciousness. There is a neuron (or a representation) in the brain linked to the idea of a dualistic world, divided between matter and thought. But this framework of thought leads nowhere: and it is necessary to deliberately choose to stop thinking in this representation in order to stop being struck by the sensation that this problem exists.

This is consistent with people not falling into this framing and not being confused by the problem at all.

To stop being afraid of the dark, your neuron of the Ghost needs to go away, but that is not a simple cognitive move. It’s even almost impossible to do it by force, you just need to be patient.

To stop being confused by the Hard problem, your neural representations with the explanatory gap need to be pruned; That’s not a simple cognitive move. That’s like an anti-leap of faith.

But this is a salutary move that you can train yourself to make to stop believing in God, to stop believing in ghosts, to stop believing in vitalism, etc…

Chapter 8: Digital Sentience

If we reuse the pyramid to see which features GPT-4 exhibits, we get this:

Is GPT-4 phenomenally conscious? Is a table without feet still a table? Is a carrot that is blue still a carrot? Are viruses part of life? I’m not interested in those questions.

What’s really interesting is that we can see with AIs that the different sub-features of cognition can appear completely independently of each other, in different AIs. There really are many degrees of freedom.

And I’m much more interested in questions like: “Is the AI able of Auto Replication and Adaption”.

So that’s my position: I’m an eliminativist. I think we should eliminate the world consciousness and focus on the lower-level features. And I think the hard problem is a virus.

I hope this presentation can act as a vaccine, and save you some time.

Solving the meta-problem: A methodology to reconstruct cleanly the notion of consciousness for AIs |

Nate Soares says: “Having done this exercise at least in part, I [...] assert that consciousness/qualia can be more-or-less rescued, and that there is a long list of things an algorithm has to do to ‘be conscious’ / ‘have qualia’ in the rescued sense.” Here is a methodology that enables to reconstruct such a list. We’ll again approach the question of digital sentience through this new prism of the meta-problem, i.e. being able to explain why AIs would talk about consciousness. There’s a problem in digital sentience, and it’s called the Gaming problem: AIs can talk about consciousness but only repeat like parrots what they’ve seen in the dataset. Fortunately, there’s a solution to this problem: We simulate AIs talking about philosophy. The AIs in the simulation initially don’t know what consciousness is. We filter out anything that talks about consciousness in the training texts and see if the philosopher AIs start to invent the notion of a hard problem after a while in the simulation. I define “being conscious” as “being able to reinvent the hard problem of consciousness”. Note that this is an arbitrary criterion, but that this criterion is much stricter than what we ask of humans. Most people are not at the level of David Chalmers who was able to invent the meme by himself. If they do reinvent the hard problem, it would be a big sign that the AIs in the simulation are “conscious” (in the reconstructed sense). I assert that this experiment would solve the hard problem, because we could look at the logs,[4] and the entire causal history of the AI that utters the words “Hard pro-ble-m of Con-scious-ness” would be understandable. Everything would just be plainly understandable mechanistically, and David Chalmer would need to surrender. What’s more, I claim we’ll be able to create such a working simulation in the future (even if I don’t technically justify this here). |

It was clear to me by then that nobody had the answers I craved — and I was hardly likely to come up with them myself; my intellectual skills were, at best, mediocre. It came down to a simple choice: I could waste time fretting about the mysteries of consciousness, or, like everybody else, I could stop worrying and get on with my life.

--- From Greg Egan, Learning to Be Me.

Thanks heaps to everyone who helped me along the way, especially people who posted some thoughts online.

Further Exploration

Here are some additional references:

For everyone: Explore major milestones in the Theory of consciousness in the Lesswrong Wiki: Consciousness—Lesswrong Wiki

If you are still confused,If my intuition pumps were not sufficient, you should:

First, read Consciousness as a conflationary alliance term, from Andrew Critch.

Then, read Dissolving Confusion about Consciousness. The other essays in the collection Essays on Reducing Suffering from Bryan Tomasik are profoundly insightful, especially for those interested in the moral implications of our understanding of consciousness.

If you agree with this post: For an in-depth scholarly approach, consider reading Luke Muehlhauser’s 2017 Report on Consciousness and Moral Patienthood. This is a substantial piece of work by the rationality community, delving into consciousness. It’s advanced material, presupposing concepts like physicalism, functionalism, illusionism, and a fuzzy view of consciousness.

If you want to discover another perspective, The Qualia Research Institute offers a unique perspective. While their metaphysical standpoint might be debatable, their research is undeniably intriguing and explores different sub-dimensions of awareness. Recommended viewings include their presentations at the Harvard Science of Psychedelics Club: The Hyperbolic Geometry of DMT Experiences, and Logarithmic Scales of Pleasure and Pain, which are cool phenomena that remain to be fully understood in the meta-problem prisms.

Addendum: AI Safety & Situational Awareness

As I said in the beginning, I think it’s beneficial to be deconfused about consciousness for conceptual research in AI Safety. When I present in class the emerging capabilities of AI models that could pose problems, I often cite those given in the paper ‘Model Evaluation for Extreme Risks,’ such as cyber-offense, manipulation, deception, weapon acquisition, long horizon planning, AI development, situational awareness, and self-proliferation. After explaining each of these capabilities, I am often asked the following question: ‘But hum… Situational Awareness is strange because that would mean that the model is conscious. Is that possible?’

Damn. How to give a good answer in a limited time?

Here is the answer I often give:

Good question!

I think it’s better not to use the word consciousness for now, which will take us too far.

Let’s calmly return to the definition of situational awareness. If we simplify, situational awareness literally means ‘being aware of the situation,’ that is, being able to use contextual information related to the situation. For example, time or geographic position are contextual information. Models will be selected to use this information because they perform better if they can use it, for example, for automatic package delivery.

For instance, I am situationally aware because I know my first name, I know that I am a human; when I was little, I read that humans are made up of cells that contain DNA. All this contextual information about myself allows me to be more competent.

In the same way, AIs will be selected to be competent and to be able to use information about their situation will be selected. It’s not that mysterious.

One variable that matters for situational awareness is knowing if someone is observing you at a given moment. Children learn very quickly to behave differently depending on whether they are observed or not; in the same way, an AI could also adopt different behaviors depending on whether it knows it is being observed or not.

And, of course, situational awareness is not binary. A child has less SA than an adult.

Situational awareness can be broken down into many sub-dimensions, and a recent paper shows that LLMs exhibit emerging signals of situational awareness.

Just as the word ‘intelligence’ is not monolithic, and it is better to study the different dimensions of the AI capabilities spectrum (as suggested by Victoria Krakovna in ‘When discussing AI risks, talk about capabilities, not intelligence’), I think we should avoid using the word ‘consciousness’ and talk about the different capabilities, including the different dimensions of situational awareness capacities of AIs.”

Addendum: From Pain to Meta-Ethics

What is pain? Why is pain bad?

It’s the same trick: we shouldn’t ask, “Why is pain negative,” but “Why do we think pain is negative?” Here’s the response in the form of a genealogy of morals:

Detectors for intense heat are extremely useful. Organisms without these detectors are replaced by those who react reflexively to heat. Muscle fatigue detectors are also extremely useful: Organisms without these detectors are replaced by those that react to these signals and conserve their muscle tissue. The same goes for the dangerous mechanical and chemical stimulation conveyed by type-C fibers.

In the brain, the brain constantly processes different signals. However, signals from type-C fibers are hard-coded as high-priority signals. The brain’s attention then focuses on these signals, and in cases of severe pain, it’s impossible to focus on anything else.

Next, we start to moan, scream, and cry to alert other tribe members that we are in trouble.

There are many different forms of suffering: Physical Pain, Emotional Suffering, Psychological Trauma, Existential Anguish, Suffering from Loss, Chronic Illnesses, and Addiction. Suffering is a broad term that includes various phenomena. However, at its core, it refers to states that individuals could choose to remove if given the option.

If you concentrate sufficiently on pain and are able to deconstruct it dimension by dimension, feature by feature, you will understand that it’s a cluster of sensations not that different from other sensations. If you go through this process, you can even become like a Buddhist monk who is able to self-immolate without suffering.

At the end of the day, asking why pain is bad is tautological. “Bad” is a label that was created to describe a cluster of things that should be avoided, including pain.

What is Ethics?

We can continue the previous story:

Values: In the previous story, the tribe organizes itself by common values, and tribe members must learn these values to be good members of the tribe. Tribes coordinated through these values/rules/laws/protocols are tribes that survive longer. The village elder, stroking his beard, says: “Ah, X1 is good, X2 is bad.” This statement transmits the illusion of morality to the tribe members. It is a necessary illusion that is shared by the members of the tribe in order for the tribe to function effectively. It can be thought of as a mental meme, a software downloaded into the minds of individuals that guides their behavior appropriately.

Prophets and Philosophers then attempt to systematize this process by asking, “What criteria determine the goodness of X?” They create ad hoc verbal rules that align with the training dataset X1, X2, … XN, Y1, Y2, …,YN. One rule that fits the dataset reasonably well is ‘Don’t kill people of your own tribe’. That gets written in the holy book alongside other poor heuristics.

Flourishing Arab civilization: Merchants invent trade, and then mathematicians invent money! It’s really great to assign numbers to things, as it facilitates commerce.

Ethicists: Philosophers familiar with the use of numbers then try to assign values to different aspects of the world: “X1 is worth 3 utils! X2 is worth 5 utils!”. They call themselves utilitarians. Philosophers who are less happy with the use of numbers prefer sticking to hardcoded rules. They call themselves Deontologists. They often engage in arguments with each other.

Meta-ethicists: Philosophers who are witnessing disagreements among philosophers about what is the best system start writing about meta-ethics. Much of what they say is meh.[5] Just as the majority of intellectual production in theology is done by people who are confused about the nature of the world, it seems to me that the majority of intellectual production in moral philosophy is done by people who are self-selected to spend years on those problems.

And note that I’ve never crossed Hume’s guillotine during the story, which was my answer to the meta-problem of pain.

- ^

For those who are wondering, the number is 4 on the bottom left, and there is no number on the top right.

- ^

It’s called epiphenomenalism because mental phenomena are interpreted as epiphenomena, i.e., phenomena generated by the brain but which have no feedback effect on it.

- ^

Yud also says: If there were no health reason to eat cows I would not eat them

- ^

Look at the logs, or use inference functions

- ^

Go read this SEP article if you don’t believe me.

I quite liked the way that this post presented your intellectual history on the topic, it was interesting to read to see where you’re coming from.

That said, I didn’t quite understand your conclusion. Starting from Chap. 7, you seem to be saying something like, “everyone has a different definition for what consciousness is; if we stop treating consciousness as being a single thing and look at each individual definition that people have, then we can look at different systems and figure out whether those systems have those properties or not”.

This makes sense, but—as I think you yourself said earlier in the post—the hard problem isn’t about explaining every single definition of consciousness that people might have? Rather it’s about explaining one specific question, namely:

You cite Critch’s list of definitions people have for consciousness, but none of the three examples that you quoted seem to be talking about this property, so I don’t see how they’re related or why you’re bringing them up.

With regard to this part:

This part seems to be quite a bit weaker than what I read you to be saying earlier. I interpreted most of the post to be saying “I have figured out the solution to the problem and will explain it to you”. But this bit seems to be weakening it to “in the future, we will be able to create AIs that seem phenomenally conscious and solve the hard problem by looking at how they became that”. Saying that we’ll figure out an answer in the future when we have better data isn’t actually giving an answer now.

Thank you for the kind words!

Okay, fair enough, but I predict this would happen: in the same way that AlphaGo rediscovered all of chess theory, it seems to me that if you just let the AIs grow, you can create a civilization of AIs. Those AIs would have to create some form of language or communication, and some AI philosopher would get involved and then talk about the hard problem.

I’m curious how you answer those two questions:

Let’s say we implement this simulation in 10 years and everything works the way I’m telling you now. Would you update?

What is the probability that this simulation is possible at all?

If you expect to update in the future, just update now.

To me, this thought experiment solves the meta-problem and so dissolves the hard problem.

Well, it’s already my default assumption that something like this would happen, so the update would mostly just be something like “looks like I was right”.

You mean one where AIs that were trained with no previous discussion of the concept of consciousness end up reinventing the hard problem on their own? 70% maybe.

That sounds like it would violate conservation of expected evidence:

I don’t see how it does? It just suggests that a possible approach by which the meta-problem could be solved in the future.

Suppose you told me that you had figured out how to create cheap and scalable source of fusion power. I’d say oh wow great! What’s your answer? And you said that, well, you have this idea for a research program that might, in ten years, produce an explanation of how to create cheap and scalable fusion power.

I would then be disappointed because I thought you had an explanation that would let me build fusion power right now. Instead, you’re just proposing another research program that hopes to one day achieve fusion power. I would say that you don’t actually have it figured it out yet, you just think you have a promising lead.

Likewise, if you tell me that you have a solution to the meta-problem, then I would expect an explanation that lets me understand the solution to the meta-problem today. Not one that lets me do it ten years in the future, when we investigate the logs of the AIs to see what exactly it was that made them think the hard problem was a thing.

I also feel like this scenario is presupposing the conclusion—you feel that the right solution is an eliminativist one, so you say that once we examine the logs of the AIs, we will find out what exactly made them believe in the hard problem in a way that solves the problem. But a non-eliminativist might just as well claim that once we examine the logs of the AIs, we will eventually be forced to conclude that we can’t find an answer there, and that the hard problem still remains mysterious.

Now personally I do lean toward thinking that examining the logs will probably give us an answer, but that’s just my/your intuition against the non-eliminativist’s intuition. Just having a strong intuition that a particular experiment will prove us right isn’t the same as actually having the solution.

hmm, I don’t understand something, but we are closer to the crux :)

You say:

To the question, “Would you update if this experiment is conducted and is successful?” you answer, “Well, it’s already my default assumption that something like this would happen”.

To the question, “Is it possible at all?” You answer 70%.

So, you answer 99-ish% to the first question and 70% to the second question, this seems incoherent.

It seems to me that you don’t bite the bullet for the first question if you expect this to happen. Saying, “Looks like I was right,” seems to me like you are dodging the question.

Hum, it seems there is something I don’t understand; I don’t think this violates the law.

I agree I only gave the skim of the proof, it seems to me that if you can build the pyramid, brick by brick, then this solved the meta-problem.

for example, when I give the example of meta-cognition-brick, I say that there is a paper that already implements this in an LLM (and I don’t find this mysterious because I know how I would approximately implement a database that would behave like this).

And it seems all the other bricks are “easily” implementable.

Yeah I think there’s some mutual incomprehension going on :)

For me “the default assumption” is anything with more than 50% probability. In this case, my default assumption has around 70% probability.

Sorry, I don’t understand this. What question am I dodging? If you mean the question of “would I update”, what update do you have in mind? (Of course, if I previously gave an event 70% probability and then it comes true, I’ll update from 70% to ~100% probability of that event happening. But it seems pretty trivial to say that if an event happens then I will update to believing that the event has happened, so I assume you mean some more interesting update.)

I may have misinterpreted you; I took you to be saying “if you expect to see this happening, then you might as well immediately update to what you’d believe after you saw it happen”. Which would have directly contradicted “Equivalently, the mere expectation of encountering evidence—before you’ve actually seen it—should not shift your prior beliefs”.

Okay. But that seems more like an intuition than even a sketch of a proof to me. After all, part of the standard argument for the hard problem is that even if you explained all of the observable functions of consciousness, the hard problem would remain. So just the fact that we can build individual bricks of the pyramid isn’t significant by itself—a non-eliminativist might be perfectly willing to grant that yes, we can build the entire pyramid, while also holding that merely building the pyramid won’t tell us anything about the hard problem nor the meta-problem. What would you say to them to convince them otherwise?

Thank you for clarifying your perspective. I understand you’re saying that you expect the experiment to resolve to “yes” 70% of the time, making you 70% eliminativist and 30% uncertain. You can’t fully update your beliefs based on the hypothetical outcome of the experiment because there are still unknowns.

For myself, I’m quite confident that the meta-problem and the easy problems of consciousness will eventually be fully solved through advancements in AI and neuroscience. I’ve written extensively about AI and path to autonomous AGI here, and I would ask people: “Yo, what do you think AI is not able to do? Creativity? Ok do you know....”. At the end of the day, I would aim to convince them that anything humans are able to do, we can reconstruct everything with AIs. I’d put my confidence level for this at around 95%. Once we reach that point, I agree I think it will become increasingly difficult to argue that the hard problem of consciousness is still unresolved, even if part of my intuition remains somewhat perplexed. Maintaining a belief in epiphenomenalism while all the “easy” problems have been solved is a tough position to defend—I’m about 90% confident of this.

So while I’m not a 100% committed eliminativist, I’m at around 90% (when I was at 40% in chapter 6 in the story). Yes, even after considering the ghost argument, there’s still a small part of my thinking that leans towards Chalmers’ view. However, the more progress we make in solving the easy and meta-problems through AI and neuroscience, the more untenable it seems to insist that the hard problem remains unaddressed.

I actually think a non-eliminativist would concede that building the whole pyramid does solve the meta-problem. That’s the crucial aspect. If we can construct the entire pyramid, with the final piece being the ability to independently rediscover the hard problem in an experimental setup like the one I described in the post, then I believe even committed non-materialists would be at a loss and would need to substantially update their views.

So I’ve been trying to figure out whether or not to chime in here, and if so, how to write this in a way that doesn’t come across as combative. I guess let me start by saying that I 100% believe your emotional struggle with the topic and that every part of the history you sketch out is genuine. I’m just very frustrated with the post, and I’ll try to explain why.

It seems like you had a camp #2 style intuition on Consciousness (apologies for linking my own post but it’s so integral to how I think about the topic that I can’t write the comment otherwise), felt pressure to deal with the arguments against the position, found the arguments against the position unconvincing, and eventually decided they are convincing after all because… what? That’s the main thing that perplexes me; I don’t understand what changed. The case you lay out at the end just seems to be the basic argument for illusionism that Dennett et al have made over 20 years ago.

This also ties in with a general frustration that’s not specific to your post; the fact that we can’t seem to get beyond the standard arguments for both sides is just depressing to me. There’s no semblance of progress on this topic on LW in the last decade.

You mentioned some theories of consciousness, but I don’t really get how they impacted your conclusion. GWT isn’t a camp #2 proposal at all as you point out. IIT is one but I don’t understand your reasons for rejection—you mentioned that it implies a degree of panpsychism, which is true, but I believe that shouldn’t affect its probability one way or another?[1] (I don’t get the part where you said that we need a threshold; there is no threshold for minimal consciousness in IIT.) You also mention QRI but don’t explain why you reject their approach. And what about all the other theories? Like do we have any reason to believe that the hypothesis space is so small that looking at IIT, even if you find legit reasons to reject it, is meaningful evidence about the validity of other ideas?

If the situation is that you have an intuition for camp #2 style consciousness but find it physically implausible, then there’s be so many relevant arguments you could explore, and I just don’t see any of them in the post. E.g., one thing you could do is start from the assumption that camp #2 style consciousness does exist and then try to figure out how big of a bullet you have to bite. Like, what are the different proposals for how it works, and what are the implications that follow? Which option leads to the smallest bullet, and is that bullet still large enough to reject it? (I guess the USA being conscious is a large bullet, but why is that so bad, and what the approaches that avoid the conclusion, and how bad are they? Btw IIT predicts that the USA is not conscious.) How does consciousness/physics even work on a metaphysical level; I mean you pointed out one way it doesn’t work, which is epiphenomenalism, but how could it work?

Or alternatively, what are the different predictions of camp #2 style consciousness vs. inherently fuzzy, non-fundamental, arbitrary-cluster-of-things-camp-#1 consciousness? What do they predict about phenomenology or neuroscience? Which model gets more Bayes points here? They absolutely don’t make identical predictions!

Wouldn’t like all of this stuff be super relevant and under-explored? I mean granted, I probably shouldn’t expect to read something new after having thought about this problem for four years, but even if I only knew the standard arguments on both sides, I don’t really get the insight communicated in this post that moved you from undecided or leaning camp #2 to accepting the illusionist route.

The one thing that seems pretty new is the idea that camp #2 style consciousness is just a meme. Unfortunately, I’m also pretty sure it’s not true. Around half of all people (I think slightly more outside of LW) have camp #2 style intuitions on consciousness, and they all seem to mean the same thing with the concept. I mean they all disagree about how it works, but as far as what it is, there’s almost no misunderstanding. The talking past each other only happens when camp #1 and camp #2 interact.

Like, the meme hypothesis predicts that the “understanding of the concept” spread looks like this:

but if you read a lot of discussions, LessWrong or SSC or reddit or IRL or anywhere, you’ll quickly find that it looks like this:

This shows that if you ask camp #1 people—who don’t think there is a crisp phenomenon in the territory for the concept—you will get many different definitions. Which is true but doesn’t back up the meme hypothesis. (And if you insist in a definition, you can probably get camp #2 people to write weird stuff, too. Especially if you phrase it in such a way that they think they have to point to the nearest articulate-able thing rather than gesture at the real thing. You can’t just take the first thing people about this topic say without any theory of mind and take it at face value; most people haven’t thought much about the topic and won’t give you a perfect articulation of their belief.)

So yeah idk, I’m just frustrated that we don’t seem to be getting anywhere new with this stuff. Like I said, none of this undermines your emotional struggle with the topic.

We know probability consists of Bayesian Evidence and prior plausibility (which itself is based on complexity). The implication that IIT implies panpsychism doesn’t seem to affect either of those—it doesn’t change the prior of IIT since IIT is formalized so we already know its complexity, and it can’t provide evidence one way or another since it has no physical effect. (Fwiw I’m certain that IIT is wrong, I just don’t think the panpsychism part has anything to do with why.)

Thanks for jumping in! And I’m not that emotionally struggling with this, this was more of a nice puzzle, so don’t worry about it :)

I agree my reasoning is not clean in the last chapter.

To me, the epiphany was that AI would rediscover everything like it rediscovered chess alone. As I’ve said in the box, this is a strong blow to non-materialistic positions, and I’ve not emphasized this enough in the post.

I expect AI to be able to create “civilizations” (sort of) of its own in the future, with AI philosophers, etc.

Here is a snippet of my answer to Kaj, let me know what you think about it:

If the Turing thesis is correct, AI can, in principle, solve every problem a human can solve. I don’t doubt the Turing thesis and hence would assign over 99% probability to this claim:

(I’m actually not sure where your 5% doubt comes from—do you assign 5% on the Turing thesis being false, or are you drawing a distinction between practically possible and theoretically possible? But even then, how could anything humans do be practically impossible for AIs?)

But does this prove eliminativism? I don’t think so. A camp #2 person could simply reply something like “once we get a conscious AI, if we look at the precise causal chain that leads it to claim that it is conscious, we would understand why that causal chain also exhibits phenomenal consciousness”.

Also, note that among people who believe in camp #2 style consciousness, almost all of them (I’ve only ever encountered one person who disagreed) agree that a pure lookup table would not be conscious. (Eliezer agrees as well.) This logically implies that camp #2 style consciousness is not about ability to do a thing, but rather about how that thing is done (or more technically put, it’s not about the input/output behavior of a system but an algorithmic or implementation-level description). Equivalently, it implies that for any conscious algorithm A, there exists a non-conscious algorithm A′ with identical input/output behavior (this is also implied by IIT). Therefore, if you had an AI with a certain capability, another way that a camp #2 person could respond is by arguing that you chose the wrong algorithm and hence the AI is not conscious despite having this capability. (It could be the case that all unconscious implementations of the capability are computationally wasteful like the lookup table and hence all practically feasible implementations are conscious, but this is not trivially true, so you would need to separately argue for why you think this.)

Epiphenomenalism is a strictly more complex theory than Eliminativism, so I’m already on board with assigning it <1%. I mean, every additional bit in a theory’s minimal description cuts its probability in half, and there’s no way you can specify laws for how consciousness emerges with less than 7 bits, which would give you a multiplicative penalty of 1⁄128. (I would argue that because Epiphenomenalism says that consciousness has no effect on physics and hence no effect on what empirical data you receive, it is not possible to update away from whatever prior probability you assign to it and hence it doesn’t matter what AI does, but that seems beside the point.) But that’s only about Epiphenomenalism, not camp #2 style consciousness in general.

I’ve traveled these roads too. At some point I thought that the hard problem reduced to the problem of deriving an indexical prior, a prior on having a particular position in the universe, which we should expect to derive from specifics of its physical substrate, and it’s apparent that whatever the true indexical prior is, it can’t be studied empirically, it is inherently mysterious. A firmer articulation of “why does this matter experience being”. Today, apparently, I think of that less as a deeply important metaphysical mystery and more just as another imperfect logical machine that we have to patch together just well enough to keep our decision theory working. Last time I scratched at this I got the sense that there’s really no truth to be found beyond that. IIRC Wei Dai’s UDASSA answers this with the inverse kolmogorov complexity of the address of the observer within the universe, or something. It doesn’t matter. It seems to work.

But after looking over this, reexamining, yeah, what causes people to talk about consciousness in these ways? And I get the sense that almost all of the confusion comes from the perception of a distinction between Me and My Brain. And that could come from all sorts of dynamics, sandboxing of deliberative reasoning due to hostile information environments, to more easily lie in external politics, and as a result of outcomes of internal (inter-module) politics (meme wont attempt to supercede gene if meme is deluded into thinking it’s already in control, so that’s what gene does).

That sort of sandboxing dynamic arises inevitably from other-modelling. In order to simulate another person, you need to be able to isolate the simulation from your own background knowledge and replace it with your approximations of their own, the simulation cannot feel the brain around it. I think most peoples’ conception of consciousness is like that, a simulation of what they imagine to be themselves, similarly isolated from most of the brain.

Maybe the way to transcend it is to develop a more sophisticated kind of self-model.

But that’s complicated by the fact that when you’re doing politics irl you need to be able to distinguish other peoples’ models of you from your own model of you, so you’re going to end up with an abundance of shitty models of yourself. I think people fall into a mistake of thinking that the you that your friend sees when you’re talking is the actual you. They really want to believe it.

Humans sure are rough.

I agree. The eliminationist approach cannot explain why people talk so much about consciousness. Well, maybe it can, but the post sure doesn’t try. I think your argument that consciousness is related to self-other modeling points into the right direction, but doesn’t do the full work and in that sense falls short in the same way “emergence” does.

Perceiving is going on in the brain and my guess would be that the process of perceiving can be perceived too[1]. As there is already a highly predictive model of physical identity—the body—the simplest (albeit wrong) model is for the brain to identify its body and its observations of its perceptions.

I think that’s kind of what meditation can lead to.

If AGI can become conscious (in a way that people would agree to counts), and if sufficient self-modeling can lead to no-self via meditation, then presumably AGI would also quickly master that too.

I don’t know whether the brain nas some intra-brain neuronal feedback or observation-interpretation loops (“I see that I have done this action”). For LLMs, because they don’t have feedback-loops internally, it could be via the context window or through observing its outputs in its training data.

It should, right? But isn’t there a very large overlap between meditators and people who mystify consciousness?

Maybe in the same way as there’s also a very large overlap between people who are pursuing good financial advice and people who end up receiving bad financial advice… Some genres are majority shit, so if I characterise the genre by the average article I’ve encountered from it, of course I will think the genre is shit. But there’s a common adverse selection process where the majority of any genre, through no fault of its own, will be shit, because shit is easier to produce, and because it doesn’t work, it creates repeat customers, so building for the audience who want shit is far far more profitable.

Agree? As long as meditation practice can’t systematically produce and explain the states, it’s just craft and not engineering or science. But I think we will get there.

Nice post! The comments section is complex, indicating that even rationalists have a lot of trouble talking about consciousness clearly. This could be taken as evidence for what I take to be one of your central claims: the word consciousness means many things, and different things to different people.

I’ve been fascinated by consciousness since before starting grad school in neuroscience in 1999. Since then, I’ve thought a lot about consciousness, and what insight neuroscience (not the colored pictures of imaging, but detailed study of individual and groups of neurons’ responses to varied situations) has to say about it.

I think it has a lot to say. There are more detailed explanations available of each of the phenomena you identify as part of the umbrella term “consciousness”.

This gets at the most apt critique of this and similar approaches to denying the existence of a hard problem: “Wait! That didn’t explain the part I’m interested in!”. I think this is quite true, and better explanations are quite possible given what we know. I believe I have some, but I’m not sure it’s worth the trouble to even try to explicate them.

Over the past 25 years, I’ve discussed consciousness less and less. It’s so difficult as to create unproductive discussions a lot of the time, and frustrating misunderstandings and arguments a good bit of the time.

Thus, while I’ve wanted to write about it, there’s never been a professional or personal motivating factor.

I wonder if the advent of AGI will create such a factor. If we go through a nontrivial era of parahuman AGI, as I think we will, then I think the question of whether and how they’re conscious might become a consequential one, determining how we treat them.

It could also help determine how seriously we take AGI safety. If the answer to “is this proto-AGI conscious?” and the honest answer is “Yes, in some ways humans are, and some other ways humans aren’t”, that encourages the intuition that we should take these things seriously as a potential threat.

So, perhaps it would make sense to start that discussion now, before public debate ramps up?

If that logic doesn’t strongly hold, discussing consciousness seems like a huge time-sink taking time that would be better spent trying to solve alignment as best we can while we still have a chance.

I agree with Kaj that this is a nicely presented and readable story of your intellectual journey that teaches something on the way. I think there are a lot of parts in there that could be spun out into their own posts that would be individually more digestible to some people. My first thought was to just post this as a sequence with each chapter one post, but I think that’s not the best way, really, as the arc is lost. But a sequence of sorts would still be a good idea as some topics build upon earlier ones.

One post I’d really like to be spun out is the one about pain that you have relegated to the addendum.

Sure, “everything is a cluster” or “everything is a list” is as right as “everything is emergent”. But what’s the actual justification for pruning that neuron? You can prune everything like that.

Do you mean that the original argument that uses zombies leads only to epiphenomenalism, or that if zombies were real that would mean consciousness is epiphenomenal, or what?