AI Safety 101 : Capabilities—Human Level AI, What? How? and When?

Meta-Notes

This is a republish of a previous post, after the previous version went through heavy editing, updates and changes. The text has been expanded, content moved around/added/deleted.

Estimated reading time: 2 Hours 40 minutes reading at 100 wpm. Given the density of material covered in this chapter, if someone is encountering these arguments for the first time, I think the lesswrong projected time is too low.

Estimated reading time (including Appendices): 3 Hours 40 minutes reading at 100 wpm. The appendices are meant for people already quite familiar with topics in machine learning.

If you feel there are any mistakes or misrepresentations of anyone’s views in any section please let us know.

0.0: Overview

State-of-the-Art AI. We begin with a brief introduction to the current advancements in artificial intelligence as of 2024. We aim to acquaint readers with the latest breakthroughs across various domains such as language processing, vision, and robotics.

Foundation Models. The second section focuses on foundation models, the paradigm powering the state-of-the-art systems introduced in the previous section. We explain the key techniques underpinning the huge success of these models such as self-supervised learning, zero-shot learning, and fine-tuning. The section concludes by looking at the risks that the foundation model paradigm could pose such as power centralization, homogenization, and the potential for emergent capabilities.

Terminology. Before diving deeper, we establish the definitions that this book will be working with. This section explains why “capabilities” rather than “intelligence” is a more pragmatic measure for discussing AI risks. We also delineate key terms within the AI debate, such as Artificial General Intelligence (AGI), Artificial Super Intelligence (ASI), and Transformative AI (TAI). The section concludes by introducing the (t,n)-AGI framework which allows us to more concretely measure the level of AI capabilities on a continuous scale, rather than having to rely on discrete thresholds.

Leveraging Computation. In this section, we explore the importance of computation in AI’s progress introducing the three main variables that govern the capabilities of today’s foundation models—compute, data and parameter count. We explore scaling laws and hypotheses that predict the future capabilities of AI based on current scaling trends of these variables, offering insights into the computational strategies that could pave the way to AGI.

Forecasting. Finally, the chapter addresses the challenge of forecasting AI’s future, using biological anchors as a method to estimate the computational needs for transformative AI. This section sets the groundwork for discussing AI takeoff dynamics, including speed, polarity, and homogeneity, offering a comprehensive view of potential futures shaped by AI development.

1.0: State-of-the-Art AI

Over the last decade, the field of artificial intelligence (AI) has experienced a profound transformation, largely attributed to the successes in deep learning. This remarkable progress has redefined the boundaries of AI capabilities, challenging many preconceived notions of what machines can achieve. The following sections detail some of these advancements.

Figure: Once a benchmark is published, it takes less and less time to solve it. This can illustrate the accelerating progress in AI and how quickly AI benchmarks are “saturating”, and starting to surpass human performance on a variety of tasks. (source) , From DynaBench.

1.1: Language

Language-based tasks. There have been transformative changes in sequence and language-based tasks, primarily through the development of large language models (LLMs). Early language models in 2018 struggled to construct coherent sentences. The evolution from these to the advanced capabilities of GPT-3 (Generative Pre-Trained Transformer) and ChatGPT within less than 5 years is remarkable. These models demonstrate not only an improved capacity for generating text but also for responding to complex queries with nuanced, common-sense reasoning. Their performance in various question-answering tasks, including those requiring strategic thinking, has been particularly impressive.

GPT-4. One of the state-of-the-art language models in 2024 is OpenAI’s LLM GPT-4. In contrast with the text-only GPT-3 and follow-ups, GPT-4 is multimodal: it was trained on both text and images. This means that it can now not only generate text based on images but has also gained some other capabilities. GPT-4 saw an upgraded context window with up to 32k tokens (tokens ≈ words). The short-term memory limit of an LLM can be thought of as the model’s ability to retain information from previous tokens within a certain context window. GPT-4 is trained via next-token prediction (autoregressive self-supervised learning). In 2018 GPT-1 was barely able to count to 10, while in 2024 GPT-4 can implement complex programmatic functions among other things.

Figure: a list of “Nowhere near solved” [...] issues in AI, from “A brief history of AI”, published in January 2021 (source). They also say: “At present, we have no idea how to get computers to do the tasks at the bottom of the list”. But everything in the category “Nowhere near solved” has been solved by GPT-4 (source), except human-level general intelligence.

Scaling. Remarkably, GPT-4 is trained using roughly the same methods as GPT-1, 2, and 3. The only significant difference is the size of the model and the data given to it during training. The size of the model has gone from 1.5B parameters to hundreds of billions of parameters, and datasets have become similarly larger and more diverse.

Figure: How fast is AI Improving? (source)

We have observed that just an expansion in scale has contributed to enhanced performance. This includes improvements in the ability to generate contextually appropriate responses, and highly diverse text across a range of domains. It has also contributed to overall improved understanding, and coherence. Most of those advances in the GPT series come from increasing the size and computation power behind the models, rather than fundamental shifts in architecture or training.

Here are some of the capabilities that have been emerging in the last few years:

Few-shot and Zero-shot Learning. The model’s proficiency at understanding and executing tasks with minimal or no prior examples. ‘Few-shot’ means accomplishing the task after having seen a few examples in the context window, while ‘Zero-shot’ indicates performing the task without any specific examples (source). This also includes induction capabilities, i.e. identifying patterns and generalizing rules not present in the training, but only present in the current context window (source).

Metacognition. This refers to the ability to recognize its own knowledge and limitations, for example, being able to know the probability of the truth of something (source).

Theory of Mind. The capability to attribute mental states to itself and others, which helps in predicting human behaviors and responses for more nuanced interactions (source, source).

Tool Use. Being able to interact with external tools, like using a calculator or browsing the internet, expanding its problem-solving abilities (source).

Self-correction. The model’s ability to identify and correct its own mistakes, which is crucial for improving the accuracy of AI-generated content (source).

Figure: An example of a mathematical problem solved by GPT-4 using Chain of Thought (CoT), from the paper “Sparks of Artificial General Intelligence” (source).

Reasoning. The advancements in LLMs have also led to significant improvements in the ability to process and generate logical chains of thought and reasoning. This is particularly important in problem-solving tasks where a straightforward answer isn’t immediately available, and a step-by-step reasoning process is required. (Source)

Programming ability. In coding, AI models have progressed from basic code autocompletion to writing sophisticated, functional programs.

Scientific & Mathematical ability. In mathematics, AI’s have assisted in the subfield of automatic theorem proving for decades. Today’s models continue to assist in solving complex problems. AI can even achieve a gold medal level in the mathematical Olympiad by solving geometry problems (source).

Figure: GPT-4 solves some tasks that GPT-3.5 was unable to, like the uniform bar examination, where GPT-4 scores 90% compared to 10% for GPT-3.5. GPT-4 is also capable of vision processing, and the added vision component had only a minor impact, but it helped others tremendously. (source)

1.2: Image Generation

The leap forward in image generation is not just in accuracy, but also in the ability to handle complex, real-world images. The latter, particularly with the advent of Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) in 2014, has shown an astounding rate of progress. The quality of images generated by AI has evolved from simple, blurry representations to highly detailed and creative scenes, often in response to intricate language prompts.

Figure: An example of state-of-the-art image recognition. The Segment Anything Model (SAM) by Meta’s FAIR (Fundamental AI Research) lab, can classify and segment visual data at highly precise levels. The detection is performed without the need to annotate images. (source)

Figure: (source)

The rate of progress within a single year alone is quite astounding as is seen from the improvements between the V1 of the MidJourney image generation model in early 2022, to the V6 in December 2023.

|  |  |  |  |  |

| V1 (Feb 22) | V2 (Apr 22) | V3 (Jul 22) | V4 (Nov 22) | V5 (Mar 23) | V6 (Dec 23) |

Figure: MidJourney AI image generation over 2022-2023. Prompt: high-quality photography of a young Japanese woman smiling, backlighting, natural pale light, film camera, by Rinko Kawauchi, HDR (source) | |||||

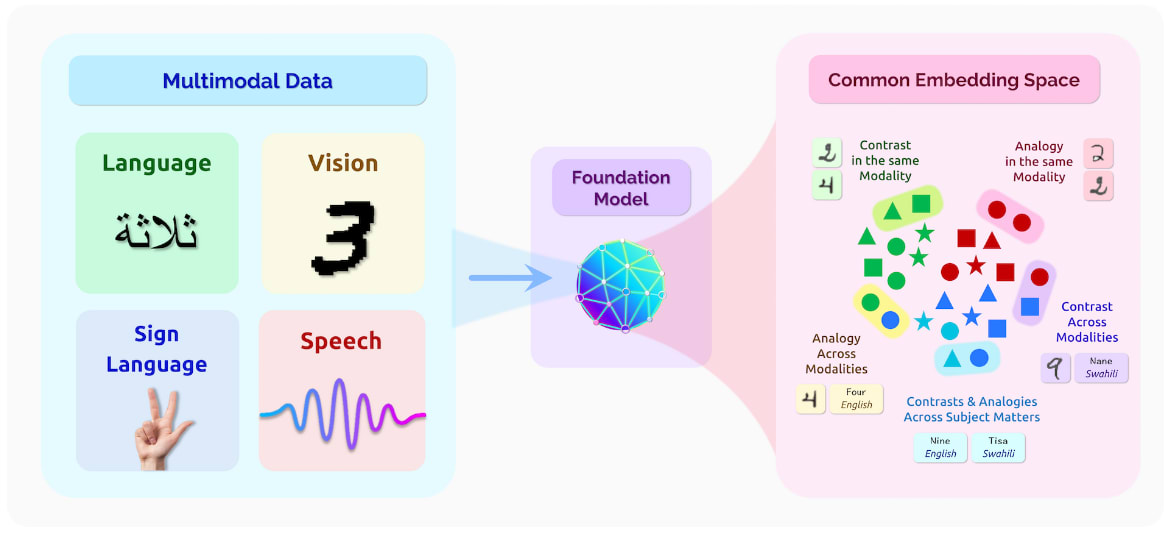

1.3: Multi & Cross modality

AI systems are becoming increasingly multimodal. This means that they can process images, text, audio, vision, and robotics using the same model. So they are trained using multiple different “modes” and can translate between them after deployment.

Cross-modality. A model is called cross-modal when the input of a model is in one modality (e.g. text) and the output is in another modality (e.g. image). The section on computer vision showed fast progress between 2014 and 2020 in cross-modality. We went from text-to-image models only capable of generating black-and-white pixelated images of faces, to models capable of generating an image of any textual prompt. More examples of cross-modality include OpenAIs Whisper (source) which is capable of speech-to-text transcription.

Multi-modality. A model is called multi-modal when both the inputs and outputs of a model can be in more than one modality. E.g. audio-to-text, video-to-text, text-to-image, etc…

Figure: Image-to-text and text-to-image multimodality from the Flamingo model. (source) | ||

DeepMind’s 2022 Flamingo model, could be “rapidly adapted to various image/video understanding tasks” and “is also capable of multi-image visual dialogue”. (source) Similarly, DeepMind’s 2022 Gato model, was called a “Generalist Agent”. It was a single network with the same weights which could “play Atari, caption images, chat, stack blocks with a real robot arm, and much more”. (source) Continuing this trend, DeepMind’s 2023 Google Gemini model could be called a Large Multimodal Model (LMM). The paper described Gemini as “natively multimodal” and claimed to be able to “seamlessly combine their capabilities across modalities (e.g. extracting information and spatial layout out of a table, a chart, or a figure) with the strong reasoning capabilities of a language model (e.g. its state-of-art-performance in math and coding)”(source)

1.4: Robotics

The field of robotics has also been progressing alongside artificial intelligence. In this section, we provide a couple of examples where these two fields are merging, highlighting some robots using inspiration from machine learning techniques to make advancements.

Figure: Researchers used Model-Free Reinforcement Learning to automatically learn quadruped locomotion in only 20 minutes in the real world instead of in simulated environments. The Figure shows examples of learned gaits on a variety of real-world terrains. (source)

Advances in robotics. At the forefront of robotic advancements is PaLM-E, a general-purpose, embodied model with 562 billion parameters that integrates vision, language, and robot data for real-time manipulator control and excels in language tasks involving geospatial reasoning. (source)

Simultaneously, developments in vision-language models have led to breakthroughs in fine-grained robot control, with models like RT-2 showing significant capabilities in object manipulation and multimodal reasoning. RT-2 demonstrates how we can use LLM-inspired prompting methods (chain-of-thought), to learn a self-contained model that can both plan long-horizon skill sequences and predict robot actions. (source)

Mobile ALOHA is another example of combining modern machine learning techniques with robotics. Trained using supervised behavioral cloning, the robot can autonomously perform complex tasks “such as sauteing and serving a piece of shrimp, opening a two-door wall cabinet to store heavy cooking pots, calling and entering an elevator, and lightly rinsing a used pan using a kitchen faucet.” (source) Such advancements not only demonstrate the increasing sophistication and applicability of robotic systems but also highlight the potential for further groundbreaking developments in autonomous technologies.

Figure: DeepMinds RT-2 can both plan long-horizon skill sequences and predict robot actions using inspiration from LLM prompting techniques (chain-of-thought). (source)

1.5: Playing Games

AI and board games. AI has made continuous progress in game playing for decades. Starting from AIs beating the world champion at chess in 1997 (source), Scrabble in 2006 (source) to DeepMind’s AlphaGo in 2016, which was good enough to defeat the world champion in the game of Go, a game assumed to be notoriously difficult for AI. Within a year, the next model AlphaZero trained through self-play had mastered multiple games of Go, chess, and shogi reaching a superhuman level after less than three days of training.

AI and video games. We started using machine learning techniques on simple Atari games in 2013 (source). By 2019, OpenAI Five defeated the world champions at DOTA2 (source), while in the same year, DeepMind’s AlphaStar beat professional esports players at StarCraft II (source). Both these games require thousands of actions in a row at a high number of actions per minute. In 2020 DeepMind MuZero model, described as “a significant step forward in the pursuit of general-purpose algorithms” (source), was capable of playing Atari games, Go, chess, and shogi without even being told the rules.

In recent years, AI’s capability has extended to open-ended environments like Minecraft, showcasing an ability to perform complex sequences of actions. In strategy games, Meta’s Cicero displayed intricate strategic negotiation and deception skills in natural language for the game Diplomacy (source).

Figure: A map of diplomacy and the dialog box where the AI negotiates. (source)

Example of Voyager: Planning and Continuous Learning in Minecraft with GPT-4. Voyager (source) stands as a particularly impressive example of the capabilities of AI in continuous learning environments. This AI is designed to play Minecraft, a task that involves a significant degree of planning and adaptive learning. What makes Voyager so remarkable is its ability to learn continuously and progressively within the game’s environment, using GPT-4 contextual reasoning abilities to plan and write the code necessary for each new challenge. Starting from scratch in a single game session, Voyager initially learns to navigate the virtual world, engage and defeat enemies, and remember all these skills in its long-term memory. As the game progresses, it continues to learn and store new skills, leading up to the challenging task of mining diamonds, a complex activity that requires a deep understanding of the game mechanics and strategic planning. The ability of Voyager to integrate new information continuously and utilize it effectively showcases the potential of AI in managing complex, changing environments and performing tasks that require a long-term buildup of knowledge and skills.

Figure: Voyager discovers new Minecraft items and skills continually by self-driven exploration, significantly outperforming the baselines. (source)

2.0: Foundation Models

Foundation models emerged in the mid-to-late 2010s, symbolizing a move away from the labor-intensive, one-model-per-task approach. These models are trained on vast, diverse datasets to learn broad patterns and skills, ready to be adapted to a multitude of tasks. Imagine them as the Swiss Army knives of the AI that can tackle everything from language translation to generating artwork. This marked a shift in strategy, to leveraging large, unlabeled datasets creating generalist models that can later be fine-tuned for specific needs.

Economics of Foundation Models. The shift towards foundation models was fueled by several factors: the explosion of data, advances in computational power, and refinements in machine learning techniques. These models are also extremely resource-intensive. Their development, training, and deployment often requires significant investment. This capital requirement comes from three main areas:

Data Acquisition. The large-scale datasets they’re trained on, often sourced from the internet. Collecting, cleaning, and updating these datasets can be expensive, especially for specialized or proprietary data.

Computational Resources. The sheer size of foundation models and the datasets used in their training demands significant computational resources, not just in terms of hardware but also the electricity needed for operation.

Research and Development. Beyond the immediate costs of data and computation, there’s the ongoing investment in research required to develop new techniques, and fine-tune the existing models. This requires both financial resources and specialized expertise.

The next section provides a deeper dive into the machinery that powers these models.

2.1: Techniques

Pre-training. This is the initial training phase on a large dataset comprising millions, if not billions, of examples. Here the models learn general patterns, structures, and knowledge.

Self-Supervised Learning (SSL). This is how we actually implement the pre-training. Unlike traditional supervised learning (SL) that relies heavily on labeled data, Self-Supervised Learning (SSL) leverages unlabeled data, enabling models to learn from the inherent structure of the data itself. The development of this technique was a crucial step because it allowed developers to not be restricted by human provided labels. Now, we can leverage nearly unlimited (unlabeled) data available on the web.

As an example of how this technique would work—suppose you have an image of a dog in a park. Instead of a human labeling the image, and then training the model to learn what the human would say, the task for the model is to predict a portion of the image given the rest of it. For instance, the model might be given the top half of the image, and its task would be to predict what the bottom half looks like.

This is repeated on a large number of such images, learning to recognize patterns and structures in this data. Through these examples, the model might learn for instance that images with trees and grass at the top often have more grass, or perhaps a path, at the bottom. It learns about objects and their context — trees and grass often appear in parks, dogs are often found in these environments, paths are usually horizontal, and so on. These learned representations can then be used for a wide variety of tasks that the model was not explicitly trained for, such as identifying dogs in images, or recognizing parks—all without any human-provided labels!

Zero & Few-Shot Learning. These are techniques in machine learning where models learn to perform tasks with very few examples. Zero-shot is when they perform well without any specific examples. This is yet another example of a technique which is useful when collecting extensive labeled data is impractical or too costly. Think about introducing a human to the concept of a cat for the first time with just a few images. Despite only seeing three examples, they learn to identify cats in a variety of contexts, not limited to the initial examples. Similarly, few-shot learning enables AI models to generalize from a minimal set of instances, identifying new examples in broader categories they’ve scarcely encountered.

Transfer Learning. Transfer learning is the next step that follows the pre-training. It’s where the model takes the general patterns, structures, and knowledge it has learned from the pre-training phase and applies them to new, related tasks. This technique hinges on the fact that knowledge acquired in one context can actually be “transferred” to enhance learning in another. It allows for the utilization of pre-existing knowledge, thereby sidestepping the need to start from scratch for every new task.

Fine-Tuning. The fine-tuning phase is where the model is specifically adapted to perform particular tasks. Fine-tuning enables the creation of versatile models capable of undertaking a wide range of tasks, from following instructions to doing programming or scientific analysis. This can be further enhanced later through methods like “Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback” (RLHF), which refines models to be more effective and user-friendly by reinforcing desirable outputs. We will talk about this technique in detail in later chapters.

Source: Bommasani Rishi et. al. (2022) “On the Opportunities and Risks of Foundation Models”

Elicitation Techniques. Prompting is how we interact with the models. It’s akin to giving the model a nudge in the right direction, ensuring that the vast knowledge it has acquired is applied in a way that’s relevant and useful. So the structure of the prompt can have a large effect on the overall performance you are able to elicit out of the system. We only briefly introduce the concept here. There are a variety of elicitation techniques like chain-of-thought (CoT) that will be discussed in later chapters.

2.2: Properties

Source: Bommasani Rishi et. al. (2022) “On the Opportunities and Risks of Foundation Models”

Efficient use of resources. Foundation models have the capacity to elevate their performance by leveraging additional data, more powerful computing resources, or advancements in model architecture. It’s not merely a technique, but a pivotal attribute that dictates how well a model can adapt and expand its capabilities. As foundation models scale, they don’t just grow; they become more nuanced, capable, and efficient in processing information, mirroring the enrichment of understanding and knowledge transfer. This makes scalability a crucial determinant in the operational efficacy of these models. We will discuss this capability further in the subsequent section on leveraging computation.

Generalization. This is the cornerstone of foundation models’ effectiveness, enabling these AI systems to perform accurately on data they haven’t previously encountered. This trait ensures the models remain versatile and reliable across various applications, making them indispensable tools in the AI toolkit. However, even though foundation models are displaying increasingly better generalization of capabilities, more research is needed to ensure the generalization of goals as well. The issue of capability generalization without goal generalization is something we will tackle in depth in subsequent chapters.

Multi-modality. This is a newer property that is still emerging as of 2024, but is expected to become extremely relevant as the years progress. This opinion was reflected by Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI in a conversation with Bill Gates, where he mentioned “Multimodality will definitely be important. Speech in, speech out, images, eventually video. Clearly, people really want that. Customizability and personalization will also be very important.” (source)

We slightly touched on these capabilities in the section on state-of-the-art AI. This characterizes the capability of foundation models to process, interpret, and generate insights from various types of data, or “modalities,” such as text, images, audio, and video. The power of multimodality in foundation models lies in its potential to create richer, more nuanced representations of information. By leveraging multiple forms of data, these models can establish deeper connections and uncover insights that might be missed when data types are considered in isolation. This can be considered similar to humans, where our comprehension of the environment is enhanced by integrating visual, auditory, and textual information, thereby offering a more holistic understanding of our surroundings.

2.3: Limitations & Risks

Balancing Cost and Accessibility. The development and training of foundation models require a significant investment, posing a delicate balance between cost and accessibility. While adapting an existing model for a specific task might be more cost-effective than developing a new one from scratch, potentially democratizing access to cutting-edge AI capabilities, the substantial initial costs risk centralizing power among a few well-resourced entities. This concentration of power can exacerbate existing inequalities, as only wealthy organizations or nations can afford to develop and deploy these advanced systems.

Additionally, there is an ongoing debate about whether these models should be open-sourced. Open-sourcing can democratize access, allowing more people to benefit and contribute to advancements. However, it also increases the risk of misuse, as malicious actors could exploit these powerful tools for harmful purposes, such as generating deepfakes or coordinating cyberattacks. We talk more about these issues in the chapters on the risk landscape and AI governance.

Homogenization. The process of homogenization refers to the situation where an increasing number of AI systems are merely fine-tuned versions of the same foundation models. Therefore, if a foundation model has certain biases or failure modes, these could potentially be propagated to all models that are fine-tuned from this foundation. This is a significant risk because if the same problem exists in the foundation model, it could manifest across many different models and applications, leading to widespread and potentially correlated failures. For example, if a foundation model has been trained on data that has gender or racial biases, these biases could propagate to all models fine-tuned from it, leading to biased decisions across various applications, whether it be text generation, sentiment analysis, or even predictive policing.

Emergence. Increasing the centralization of general-purpose capabilities within a single model might result in unexpected and unexplainable behavior arising as a function of scale. This describes the phenomenon where foundation models exhibit complex behaviors or outputs not explicitly programmed, arising unpredictably from some underlying learned patterns. Emergent qualities rather than their explicit construction provide immense benefits, but this also makes foundation models hard to understand, predict, and control. This lack of predictability and control is a significant concern when these models are used in high-stakes domains. If they fail in ways that are outside our current understanding and expectations, these failures could be particularly problematic when combined with homogenization described above. The same foundation model integrated into multiple critical functions could lead to correlated failures that span multiple critical functions or failsafes. This phenomenon of emergence is also talked about in more detail in subsequent sections.

We are only introducing the notion of emergence here, but we talk more about unexpected behavior due to scale in the section on scaling laws, as well as explore different arguments around emergence in the chapter on the landscape of AI risks.

3.0: Terminology

This section continues the discussion on the terminology necessary to discuss AI capabilities. It focuses in particular on certain thresholds that we might reach in the cognitive capabilities of these AI models.

3.1: Capabilities vs. Intelligence

The difficulty of defining and measuring intelligence. Defining something is akin to establishing a standard unit of measurement, such as a gram for weight or a meter for distance. This foundational step is critical for assessment, understanding, and measurement. However, crafting a universally accepted definition of intelligence has proven to be a formidable challenge. Approaches tried in the past such as the Turing test, endeavored to test if AI systems think or act like humans. These criteria are outdated, and we need much more precise benchmarking not for systems that think or act purely rationally. (source) Since then there have been many attempts made at formalizing definitions of “intelligence”, “machine intelligence”(source), “human-like general intelligence” (source), and so on. The difficulty in finding a universally agreed-upon definition comes from several key factors:

Multidimensional Nature: Intelligence is not a singular, linear attribute but a composite of various cognitive abilities including problem-solving, adaptability, learning capacity, and understanding complex concepts. It is multidimensional and context-dependent, which makes it challenging to condense into a single, universally agreed-upon definition.

Field-Specific Interpretations: Different academic disciplines approach intelligence through diverse lenses. Psychologists may emphasize cognitive skills measurable by IQ tests. Computer scientists might view intelligence as the capability of machines to perform tasks requiring human-like cognitive processes. Neuroscientists approach intelligence from a biological standpoint, focusing on the brain’s physical and functional properties, whereas anthropologists and sociologists might perceive intelligence as culturally relative, emphasizing social and emotional competencies. Philosophers’ intelligence abstractly, its nature and components, including abstract thought, self-awareness, creativity, etc… Each perspective enriches the discussion but complicates the formation of a consensus.

Human-centric Bias: Many existing definitions of intelligence are rooted in human cognition, posing limitations when considering AI systems or non-human intelligence. This bias suggests a need for broader criteria that can encompass intelligence in all its forms, not just those familiar to human cognition.

Implementation Independence: Intelligence manifests across the natural world, making its measurement across species or entities particularly challenging. An effective definition should be impartial, recognizing intelligence even when it operates in unfamiliar or not fully understood ways.

Abstract and Ambiguous Nature: Intelligence is an abstract concept and abstract concepts often carry inherent ambiguities. This ambiguity can lead to different interpretations and debates about what constitutes “real” or “true” intelligence.

Due to all these listed reasons, when discussing artificial intelligence, particularly in the context of risks and safety, it’s often more effective and precise to focus on “capabilities” rather than “intelligence”.

Defining Capabilities. The term “capabilities” encompasses the specific, measurable abilities of an AI system. These can range from pattern recognition across large datasets, learning and adapting from the environment to mastering complex tasks traditionally requiring human intelligence. Unlike the abstract qualities often associated with the notion of intelligence, such as consciousness or self-awareness, capabilities are directly observable and quantifiable aspects of AI performance.

Propensity. An additional concrete measurable variable in addition to capabilities is propensity. We can break down risks from AI into whether a model has certain dangerous capabilities, and additionally whether it has the tendency to harmfully apply its capabilities. This tendency is called propensity, and measures how likely an AI model is to use its capabilities in harmful ways. (source)

Decomposing capabilities. Capabilities might still be a little too general. We can break them down into specific, measurable capabilities and more complex, fuzzy capabilities:

Specific Capabilities: These are well-defined tasks that can be quantitatively measured using benchmarks. For example, the Massive Multitask Language Understanding (MMLU) benchmark evaluates an AI model’s performance across a range of academic subjects, providing clear metrics for specific cognitive tasks like language comprehension, mathematics, and science. (source) These benchmarks offer concrete data points to assess an AI’s growth in specific distinct areas, making it easier to track progress and compare different models.

Fuzzy Capabilities: These refer to more complex and nuanced abilities that are harder to quantify. Examples include persuasion, deception, and situational awareness. Instead of just answering questions in a multiple choice test, these capabilities often require specialized evaluations and in depth subjective assessments. For instance, measuring an AI’s ability to persuade might involve analyzing its performance in debate scenarios or its effectiveness in generating convincing arguments. Similarly, assessing deception could involve testing the AI’s ability to generate misleading statements or conceal information. Situational awareness might be evaluated by how well an AI understands and responds to dynamic environments or unexpected changes. We talk in much more depth about concrete formalizations of different dangerous capabilities, as well as ways to measure and evaluate capabilities in the chapter on evaluations.

Advantages of Focusing on Capabilities. Focusing on capabilities offers a clearer and more pragmatic framework for discussing AI systems, particularly when evaluating potential risks. This approach facilitates direct comparisons of AI abilities with human skills, sidestepping the ambiguities tied to the concept of intelligence. For instance, rather than debating an AI system’s intelligence relative to humans, we can assess its proficiency in specific tasks, enabling a more straightforward understanding and management of AI-related risks. (source) Talking about capabilities instead of intelligence gives us the following advantages:

Ambiguity of Intelligence & Measurement challenges: The concept of intelligence is fraught with ambiguity and subjective interpretations, complicating discussions around AI and its implications. Capabilities allow us to talk about risks, despite the lack of a universally agreed-upon definition of intelligence, and a way to measure it.

Tangibility and specificity: Capabilities refer to the specific skills or abilities of an AI system, which are often easier to measure and discuss than intelligence. For instance, we can evaluate an AI system’s capability to recognize patterns in data, learn from its environment, or perform complex tasks. Discussing AI in terms of these specific capabilities can provide a clearer and more accurate picture of what AI systems can do and how they might pose risks.

Irrelevance of human-like qualities: The discussion of AI risk is not contingent on “humanlike qualities” such as being conscious, being alive, or having human-like emotions. AI systems might have none of these qualities but still display advanced and dangerous capabilities. Focusing on “what they can do”, rather abstract qualities of “what they are” avoids these potentially confusing and irrelevant comparisons.

Despite the preference for capabilities, the discourse surrounding AI, both historically and in contemporary settings, frequently invokes “intelligence” in multiple contexts. To bridge this gap, the next few sections will present a comprehensive overview of the diverse definitions of intelligence in the field.

3.2: Definitions of advanced AI Systems

This section explores various definitions of different AI capability thresholds. The following list encompasses some of the most frequently used terms:

Intelligence: As the previous section outlined, the term intelligence is very hard to define. This book does not depend on any specific definition. A commonly accepted definition is—“Intelligence measures an agent’s ability to achieve goals in a wide range of environments.”—Legg, Shane; Hutter, Marcus; (Dec 2007) “Universal Intelligence: A Definition of Machine Intelligence”

Artificial intelligence: An AI system is a machine-based system that, for explicit or implicit objectives, infers, from the input it receives, how to generate outputs such as predictions, content, recommendations, or decisions that can influence physical or virtual environments. Different AI systems vary in their levels of autonomy and adaptiveness after deployment (OECD.AI, 2023).

Artificial Narrow Intelligence (ANI): “Weak AI—also called Narrow AI or Artificial Narrow Intelligence (ANI)—is AI trained and focused to perform specific tasks. Weak AI drives most of the AI that surrounds us today. ‘Narrow’ might be a more accurate descriptor for this type of AI as it is anything but weak; it enables some very robust applications, such as Apple’s Siri, Amazon’s Alexa, IBM Watson, and autonomous vehicles.” (source IBM)

Artificial General Intelligence (AGI): Also known as strong AI. AGI refers to systems that can apply their intelligence to a similarly extensive range of domains as humans. These AIs do not need to perform all tasks; they merely need to be capable enough to invent tools to facilitate the completion of tasks. Much like how humans are not perfectly capable in all domains but can invent tools to make problems in all domains easier to solve. AGI often gets described as “the ability to achieve complex goals in complex environments using limited computational resources. This includes efficient cross-domain optimization and the ability to transfer learning from one domain to another.”—Muehlhauser, Luke (Aug 2013) “What is AGI?”

Human-Level AI (HLAI): This term is sometimes used interchangeably with AGI, and refers to an AI system that equals human intelligence in essentially all economically valuable work. However, the term is a bit controversial as ‘human-level’ is not well-defined (source). This concept contrasts with current AI, which is vastly superhuman at certain tasks while weaker at others.

Transformative AI (TAI). One of the main things we seek to assess about any given cause is its importance: how many people are affected, and how deeply? All else equal, we’re more interested in AI developments that would affect more people and more deeply. The concept of “transformative AI” has some overlap with concepts such as “superintelligence” and “artificial general intelligence.” However, “transformative AI” is intended to be a more inclusive term, leaving open the possibility of AI systems that count as “transformative” despite lacking many abilities humans have. Succinctly, TAI is a “potential future AI that triggers a transition equivalent to, or more significant than, the agricultural or industrial revolution.”- Karnofsky, Holden; (May 2016) “Some Background on Our Views Regarding Advanced Artificial Intelligence”

Artificial Super Intelligence (ASI): “This is any intellect that greatly exceeds the cognitive performance of humans in virtually all domains of interest”. — Bostrom, Nick (2014) “Superintelligence” Unlike AGI, an ASI refers to a system that not only matches but greatly exceeds human capabilities in virtually all economically valuable work or domains of interest. ASI implies a level of intelligence where the AI system can outperform the best human brains in practically every field, including scientific creativity, general wisdom, and social skills. This would mean an ASI could potentially perform tasks that humans couldn’t even comprehend.

Figure: For illustrative purposes. This graph could be criticized because it is not clear that the capabilities of those AIs can be reduced to a single dimension.

Often, these terms get used as discrete capability thresholds; that is, individuals tend to categorize an AI as potentially an AGI, an ASI, or neither. However, it is also completely possible that AI capabilities exist on a continuous scale. The next section introduces a framework for defining AGI in a more granular continuous way.

3.3: (t,n)-AGI

Defining (t,n)-AGI. Given a time frame ‘t’ to complete some cognitive task, if an AI system can outperform a human expert who is also given the time frame ‘t’ to perform the same task, then the AI system is called t-AGI for that timeframe ‘t’. (source)

Instead of outperforming on human in timeframe ‘t’, if a system can outperform ‘n’ human experts working on the task for timeframe ‘t’, then we call it a (t,n)-AGI for the specific time duration ‘t’, and number of experts ‘n’. (source)

For instance, an AI that exceeds the capability of a human expert in one second on a given cognitive task would be classified as a “one-second AGI”. This scalable measure extends to longer durations, such as one minute, one hour, or even one year, depending on the AI’s efficiency compared to human expertise within those periods.

One-second AGI: Beating humans at recognizing objects in images, basic physics intuitions (e.g. “What happens if I push a string?”), answering trivia questions, etc.

One-minute AGI: Beating humans at answering questions about short text passages or videos, common-sense reasoning, looking up facts, justifying an opinion, etc.

One-hour AGI: Beating humans at problem sets/exams, composing short articles or blog posts, executing most tasks in white-collar jobs (e.g., diagnosing patients, providing legal opinions), conducting therapy, etc.

One-day AGI: Beating humans at negotiating business deals, developing new apps, running scientific experiments, reviewing scientific papers, summarizing books, etc.

One-month AGI: Beating humans at carrying out medium-term plans coherently (e.g., founding a startup), supervising large projects, becoming proficient in new fields, writing large software applications (e.g., a new operating system), making novel scientific discoveries, etc.

One-year AGI: These AIs would beat humans at basically everything. Mainly because most projects can be divided into sub-tasks that can be completed in shorter timeframes.

Although it is more formal than the definitions provided in the previous section, the (t,n)-AGI framework does not account for how many copies of the AI run simultaneously, or how much compute/inference use. This is the question of decomposition, i.e. can complex tasks that take 1 minute (or some longer timeframe) simply be decomposed such that if we have a certain number of 1sec-AGIs, then they can still outcompete humans and effectively function as 1min-AGIs, which when combined can function at even higher thresholds.

Additionally, there is also the open question of what are the specific cognitive tasks/evaluations/benchmarks that we are going to use to measure abstract capabilities? One possible suggestion is measurements like the Abstraction and reasoning corpus (ARC benchmark) (source). Overall more work needs to be done in the area of coming up with concrete benchmarks to measure fuzzy capabilities. We talk more about these concepts in the chapters on evaluations.

As of the third quarter of 2023, we can establish a rough equivalence “from informal initial experiments, our guess is that humans need about three minutes per problem to be overall as useful as GPT-4 when playing the role of trusted high-quality labor.”(source) So existing systems can roughly be believed to qualify as one-second AGIs, and are considered to be nearing the level of one-minute AGIs.

They might be a few years away from becoming one-hour AGIs. Within this framework, Ngo anticipates that a superintelligence (ASI) could be something akin to a (one year, eight billion)-AGI, that is, an ASI could be seen as an AGI that outperforms all eight billion humans coordinating for one year on a given task. (source)

4.0: Leveraging Computation

Leveraging computation refers to the strategic utilization of computational resources to maximize the performance of AI models. We learned in the previous section that foundation models have ushered in an era where scale—model size, data volume, and computational resources—has become a cornerstone of AI capabilities. This section aims to delve further into model scaling and its pivotal role in AI capabilities.

4.1: The Bitter Lesson

What is the bitter lesson? Traditionally, AI research has predominantly designed systems under the assumption that a fixed amount of computing power will be available to the designed agent. However, over time, computing power so far has been expanding in line with Moore’s law (the number of transistors in an integrated circuit doubles every 1.5 years) (source). So researchers could either leverage their human knowledge of the domain or exploit increases in general-purpose computational methods. Theoretically, the two were mutually compatible, but as time went on it was discovered that “the biggest lesson that can be read from 70 years of AI research is that general methods that leverage computation are ultimately the most effective, and by a large margin. … [The bitter lesson teaches us] the great power of general purpose methods, of methods that continue to scale with increased computation even as the available computation becomes very great.”—Sutton, Rich (March 2019) “The Bitter Lesson”

Why is it bitter? The ‘bitter’ part of the lesson refers to a hard-learned truth: human ingenuity is not as important as we thought it was. The lesson outlines how general methods leveraging computation are ultimately more effective in achieving AI performance, often by a large margin. Despite the vast amount of human ingenuity put into crafting domain-specific knowledge and features for AI systems, computation often outperforms these human-crafted systems. It’s essential to note that, while the Bitter Lesson suggests that leveraging computation is key to advancing AI, it does not completely negate the value of human knowledge. Rather, it underscores the need to find ways to effectively combine human knowledge with computational power to achieve better performance in AI systems.

Historical evidence. The Bitter Lesson has been evidenced by the success of AI in various domains like games, vision, and language modeling. For instance, Deep Blue’s victory over chess world champion Garry Kasparov was achieved not through a detailed understanding of human chess strategies, but through leveraging a massive deep search of possible moves. Similarly, AlphaGo, which defeated Go world champion Lee Sedol, used deep learning and Monte Carlo tree search to find its moves, rather than relying on human-crafted Go strategies. Following this, AlphaZero, using self-play without any human-generated Go data, managed to beat AlphaGo. In each of these cases, the AI systems leveraged computation over human knowledge, demonstrating the Bitter Lesson in action. In 1970, the DARPA SUR (Speech Understanding Research) was held. One faction endeavored to leverage expert knowledge of words, phonemes, the human vocal tract, etc. In contrast, the other side employed newer, more statistical methods that necessitated considerably more computation, based on hidden Markov models (HMMs). This example shows yet again, that the statistical methods surpassed the human-knowledge-based methods. Since then, deep learning recurrent neural network-based or transformer-based methods have virtually dominated the field of sequence-based tasks. (source)

This subsection talked about why we started aggressively scaling out models. Due to repeated reminders of the bitter lesson, the field of AI has increasingly learned to favor general-purpose methods of search and learning. The next sections show empirical evidence for this claim delving into trends of scale in compute, dataset size, and parameter count.

4.2: Scaling Variables

This section explains the primary variables involved in scaling—compute, data, and parameters.

Compute. Compute refers to the total processing power and resources utilized for machine learning tasks measured in floating-point operations per second (FLOP/s). FLOP/s refers to a measure of computer performance and is used to quantify the number of arithmetic operations (like addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division) that a processor can perform per second. It dictates the speed and capacity of training runs. As the amount of training data increases, the model requires more information to analyze in each training run, hence increasing the total amount of processing power required. This aspect ties closely with the duration of the training process. For instance, extended training runs generally result in lower loss, and the total computational power needed partially depends on this training duration.

Dataset size. Dataset size refers to the amount of data used for training the machine learning model. The larger the dataset, the more information the model can read. Simultaneously, to read and learn from more data, the training runs also need to be generally longer, which in turn increases the total computational power needed before the model can be deemed “trained.” The relation between model size and dataset size is typically one-to-one, meaning that as we scale up the model, we also need to scale up the dataset. The quality of the data is also crucial, and not just the quantity.

Parameter Count. Parameter count represents the number of tunable variables or weights in a machine learning model. The size of the model, meaning the number of parameters, affects the compute required: the more parameters a model has, the more compute-heavy the process of calculating loss and updating weights becomes. A larger parameter count allows the model to learn more complex representations but also increases the risk of overfitting, where the model becomes too tailored to the training data and performs poorly on unseen data.

The following example offers a tangible illustration of capabilities increasing with an increasing parameter count in image generation models. In the following images, the same model architecture (Parti) is used to generate an image using an identical prompt, with the sole difference between the models being the parameter size.

350M | 750M | 3B | 20B |

|  |  |  |

Prompt: A portrait photo of a kangaroo wearing an orange hoodie and blue sunglasses standing on the grass in front of the Sydney Opera House holding a sign on the chest that says Welcome Friends! | |||

Increased numbers of parameters not only enhance image quality but also aid the network in generalizing in various ways. More parameters enable the model to generate accurate representations of complex elements, such as hands and text, which are notoriously challenging. There are noticeable leaps in quality, and somewhere between 3 billion and 20 billion parameters, the model acquires the ability to spell words correctly. Parti is the first model with the ability to spell correctly. Before Parti, it was uncertain if such an ability could be obtained merely through scaling, but it is now evident that spelling correctly is another capability gained simply by leveraging scale. (source)

Below is a chart illustrating the impact of each of these three factors on model loss.

Source: Kaplan, Jared et. al. (Jan 2020) “Scaling Laws for Neural Language Models”

The current trends in various important variables to AI scaling are as below. Trends and bottlenecks for each of these are discussed in more detail in the appendix.

Compute : The compute used to train AI models grew 4-5x yearly from 2010 to May 2024. Generally compute used to train has been growing at 4.1x per year since 2010 with a 90% confidence interval: 3.7x to 4.6x. (source)

Hardware : The computational performance (FLOP/s) is growing by 1.35x per year. With a 90% confidence interval: 1.31x to 1.40x. (source)

Data : Training dataset sizes for language models have grown by 3x per year since 2010. Given these trends, the median projected year in which most of the effective stock of publicly available human-generated text will be used in a training run is 2028, with a 90% confidence interval that we will use up all the text data between 2026 to 2033. (source)

Algorithms : Due to algorithmic efficiency the physical compute required to achieve a given performance in language models is declining at a rate of 3 times per year. With a 95% confidence interval this is a rate of decline between 2 times to 6 times. It is also worth noting that the improvements to compute efficiency explain roughly 35% of performance improvements in language modeling since 2014, vs 65% explained by increases in model scale. (source)

Costs : The cost in USD of training frontier ML models has grown by 2.4x per year since 2016, with a 90% confidence interval this is between 2x to 3.1x. This suggests that the largest frontier models will cost over a billion dollars by 2027. Today, the total amortized cost of developing Gemini Ultra, including hardware, electricity, and staff compensation, is estimated at $130 million USD, with a 90% confidence interval it is between $70 million to $290 million. (source)

4.3: Scaling Laws

Why do we care about scaling laws? Scaling laws are mathematical relationships that describe how the performance of a machine learning model changes as we vary different aspects of the model and its training process. Training large foundation models like GPT is expensive. When potentially millions of dollars are invested in training AI models, developers need to ensure that funds are efficiently allocated. Developers need to decide on an appropriate resource allocation between—model size, training time, and dataset size. Scaling laws can guide decisions between trade-offs, such as: Should a developer invest in a license to train on Stack Overflow’s data, or should they invest in more GPUs? Would it be efficient if they continued to cover the extra costs incurred by longer model training? If access to compute increases tenfold, how many parameters should be added to the model for optimal use of GPUs? For sizable language models like GPT-3, these trade-offs might resemble choosing between training a 20-billion parameter model on 40% of an internet archive or a 200-billion parameter model on just 4% of the same archive. (source) In short, scaling laws are important because they help us optimally allocate resources, and they allow us to make predictions about how changes in compute, model size, and data size will affect the performance of future models.

2020 OpenAI’s scaling laws. OpenAI developed the first generation of formal neural scaling laws in their 2020 paper “Scaling Laws for Neural Language Models”, moving away from reliance on experience and intuition. To determine the relationships between different scaling variables, some elements were held fixed while others were varied. As an example, data can be kept constant, while parameter count and training time are varied, or parameter count is kept constant and data amounts are varied, etc… This allows a measurement of the relative contribution of each towards overall performance. Such experiments allowed the development of concrete relationships that OpenAI first introduced as scaling laws.

The paper presented several scaling laws. One scaling law compares model shape and model size and found that performance correlates strongly with scale and weakly with architectural hyperparameters of model shape, such as depth vs. width. Another law compared the relative performance contribution of the different factors of scale—data, training steps, and parameter count. They found that larger language models tend to be more sample-efficient, meaning they can achieve better performance with less data. The following graph shows the relationship between the relative contributions of different factors in scaling models. The graph indicates that for optimally compute-efficient training “most of the increase should go towards increased model size. A relatively small increase in data is needed to avoid reuse. Of the increase in data, most can be used to increase parallelism through larger batch sizes, with only a very small increase in serial training time required.” (source) As an example, according to OpenAI’s results, if you get 10x more compute, you increase your model size by about 5x and your data size by about 2x. Another 10x in compute, and model size is 25x bigger, and the data size is only 4x bigger. (source)

Source: Kaplan, Jared et. al. (Jan 2020) “Scaling Laws for Neural Language Models”

What are the scaling equations? The mathematical representation of scaling laws often takes the form of power-law relationships. For instance, one of the key findings of OpenAI’s research was that model performance (measured as loss) scales as a power law with respect to model size, dataset size, and the amount of compute. The exact equations can vary depending on the specific scaling law, but a general form could be:

Where ‘k’ is a constant, and ‘a’, ‘b’, and ‘c’ are the exponents that describe how performance scales with compute, model size, and data size, respectively.

2022 Chinchilla scaling law update. In 2022, DeepMind provided an update to OpenAIs scaling laws by publishing a paper called “Training Compute-Optimal Large Language Models” (source). They choose 9 different quantities of compute, ranging from about 10^18 FLOPs to 10^21 FLOPs. They hold the compute fixed at these amounts, and then for each quantity of compute, they train many different-sized models. Because the quantity of compute is constant for each level, the smaller models are trained for more time and the larger models for less. Based on their research DeepMind concluded that for every increase in compute, you should increase data size and model size by approximately the same amount. If you get a 100x increase in compute, you should make your model 10x bigger and your data 10x bigger. (source)

To validate this law, DeepMind trained a 70-billion parameter model (“Chinchilla”) using the same compute as had been used for the 280-billion parameter model Gopher. That is, the smaller Chinchilla was trained with 1.4 trillion tokens, whereas the larger Gopher was only trained with 300 billion tokens. As predicted by the new scaling laws, Chinchilla surpasses Gopher in almost every metric. When training runs use these scaling laws, they are sometimes referred to as chinchilla optimal.

Scaling laws and future models. As for what scaling laws tell us about future AI models, they suggest that we can continue to see performance improvements as we scale up models, especially if we do so in a balanced way across compute, model size, and data size. However, they also indicate that there will be diminishing returns as we keep scaling up, and there may be practical and economic limits to how far we can push each variable.

4.4: Scaling Hypotheses

We have explored and understood foundation models, as well as observed the increasing capabilities obtained through sheer scale. There are some researchers who believe that scale is overemphasized, while others think that scale alone is enough to lead us to AGI. Researchers are divided: some argue for new paradigms or algorithms, while others believe in scaling current models to achieve AGI. In this subsection, we explore two scaling hypotheses: from considering computation as a crucial but not exclusive factor to viewing it as the primary bottleneck.

Weak Scaling Hypothesis. The weak scaling hypothesis suggests that computation is a main bottleneck to AGI, but other factors, like architecture, might also be vital. It was originally coined by Gwern, and states that “… AGI will require us to “find the right algorithms” effectively replicating a mammalian brain module by module, and that while these modules will be extremely large & expensive by contemporary standards (which is why compute is important, to give us “a more powerful tool with which to hunt for the right algorithms”), they still need to be invented & finetuned piece by piece, with little risk or surprise until the final assembly.“ - Gwern (2022) “The Scaling Hypothesis”.

LeCun’s H-Jepa architecture (source), or Richard Sutton’s Alberta Plan (source) are notable plans that might support the weak scaling hypothesis. Proponents of this hypothesis generally have a number of criticisms regarding current LLMs, which are discussed in the Appendix.

Strong Scaling Hypothesis. In the same post, Gwern also posited the strong scaling hypothesis, which states that “… once we find a scalable architecture like self-attention or convolutions, which like the brain can be applied fairly uniformly, we can simply train ever larger NNs and ever more sophisticated behavior will emerge naturally as the easiest way to optimize for all the tasks & data. More powerful NNs are ‘just’ scaled-up weak NNs, in much the same way that human brains look much like scaled-up primate brains.”—Gwern (2022) “The Scaling Hypothesis”

This hypothesis advocates that merely scaling up models on more data, modalities, and computation will resolve most current AI limitations. This strong scaling hypothesis is strongly coupled with the phenomenon that is called “The blessing of scale”, which is a general phenomenon in the literature: “The blessings of scale are the observation that for deep learning, hard problems are easier to solve than easy problems—everything gets better as it gets larger (in contrast to the usual outcome in research, where small things are hard and large things impossible). The bigger the neural net/compute/data/problem, the faster it learns, the better it learns, the stabler it learns, and so on. A problem we can’t solve at all at small n may suddenly become straightforward with millions or billions of n. “NNs are lazy”: they can do far more than we make them do when we push them beyond easy answers & cheap shortcuts. The bitter lesson is the harder and bigger, the better.” See a discussion in “The Scaling Hypothesis” for other, many examples in the literature.

Proponents include OpenAI (source)[1], Anthropic’s head Dario Amodei (source), DeepMind’s safety team (source)[2], Conjecture (source) and others.

5.0: Forecasting

This section of the chapter investigates techniques used to forecast AI timelines and takeoff dynamics.

Forecasting refers to the practice of making predictions about the future progress and impacts of AI. The aim is to anticipate when certain milestones will be reached, how AI will evolve, and what implications this could have for society. Examples of milestones are passing benchmarks, achieving mouse-level intelligence, observation of qualities such as external tool use, and long-term planning.

Forecasting in AI is the process of predicting how and when artificial intelligence will progress, focusing on key milestones like surpassing human benchmarks or achieving complex cognitive tasks. This anticipation helps us understand the potential trajectory and societal impact of AI technologies.

Importance of forecasting. Forecasting in AI is critical because it allows us to orient ourselves and prepare adequate safety measures and governance strategies according to both which capabilities are expected to emerge and when they are expected. Here are a couple of ways that timelines might affect the AI Risk case:

Resource Allocation and Urgency: Belief in imminent AI advancements (short timelines) may prompt a swift allocation of resources toward AI safety, policymaking, and immediate practical measures. This is rooted in the concern that rapid transformative AI development might leave limited time to address safety and ethical considerations.

Research Focus: The perceived timeline influences research priorities. A belief in Short timelines might steer efforts toward immediate safeguards for existing or soon-to-be-developed AI systems. In contrast, a belief in longer timelines allows for a deeper exploration of theoretical and foundational aspects of AI safety and alignment.

Career Choices: Individual decisions on engaging in AI safety work are also timeline-dependent. A short timeline perspective may drive one to contribute directly and immediately to AI safety efforts. Conversely, a belief in longer timelines might encourage further skill and knowledge development before entering the field.

Governance and Policy-making: Estimations of AI development timelines shape governance strategies, differentiating between short-term emergency measures and long-term institutional frameworks. This distinction is crucial in crafting effective policies that are responsive to the pace of AI evolution.

5.1: Zeroth-Order Forecasting

Zeroth-order forecasting, also known as reference class forecasting (source), uses the outcomes of similar past situations to predict future events. This method assumes that the best predictor of future events is the average outcome of these past events. By comparing a current situation with a reference class of similar past instances, forecasters can make more accurate predictions without needing to delve into the details of the current case. This technique effectively bypasses the complexities of individual situations by focusing on historical averages, offering a straightforward way to estimate future outcomes based on past experiences.

Understanding Reference Classes. A reference class is a collection of similar situations from the past that serves as a benchmark for making predictions. Selecting an appropriate reference class is crucial; it must closely align with the current forecasting scenario to ensure accuracy. The process involves identifying past events that share key characteristics with the situation being predicted, allowing forecasters to draw on a wealth of historical data. The challenge lies in finding a truly analogous set of instances, which requires careful analysis and expert judgment. Reference classes ground predictions in reality, providing a statistical foundation by which we can gauge the likelihood of future occurrences.

The Role of Anchors in Forecasting. Anchors are initial estimates or known data points that act as a starting point for predictions, helping to set expectations and guide subsequent adjustments. They are crucial for establishing a baseline from which to refine forecasts, offering a concrete reference that aids in calibration and reducing speculation. While an anchor typically refers to a specific data point or benchmark, a reference class encompasses a broader set of data or experiences, making both concepts integral to informed forecasting. Anchors help in grounding the forecasting process, ensuring that predictions are not made in a vacuum but are instead based on observable and reliable data.

Integrating Anchors and Reference Classes. Together, anchors and reference classes form the backbone of effective forecasting. Anchors provide a solid starting point, while reference classes offer a comprehensive historical context, allowing forecasters to approach predictions with a balanced perspective. This combination enables a more systematic and data-driven approach to forecasting, minimizing biases and enhancing the reliability of predictions.

What are some important anchors? In the context of forecasting AI progress, some key anchors to consider include:

Current machine learning (ML) anchor. The current state of machine learning systems serves as a starting point for forecasting future AI capabilities. By examining the strengths and limitations of existing ML systems, researchers can make educated guesses about the trajectory of AI development. This methodology can then be refined into the first-order forecasting methodology.

Biological anchor. Comparisons to biological systems, like the human brain, serve as useful anchors. For instance, the ‘computational capacity of the human brain’ is often used as a benchmark to estimate when AI might achieve comparable capabilities.

Compute anchor. This refers to the advancements in computing hardware that could potentially influence the speed and efficiency of AI development. It also covers the financial cost of training AI models, especially large-scale ones. Understanding this cost can provide insights into the resources required for further AI progress.

This is because both methods leverage the concept of ‘reference classes’ or ‘anchors’ to make predictions about future developments in AI.

5.2: First-Order Forecasting

First-order forecasting moves beyond the static approach of zeroth-order forecasting by considering the rate of change observed in historical data. The first-order approximation is like saying, “If the rate of change continues as it has in the past, then the future state will be this way.” It projects future developments by extrapolating current trends, assuming that the observed pace of progress or change will continue. This dynamic method of prediction considers both the present state and its historical evolution, offering predictions that reflect ongoing trends. However, it’s worth noting that such forecasts may not account for sudden shifts in progress rates, potentially leading to inaccuracies if trends dramatically change. (source)

Contrast with Zeroth-Order Forecasting. Unlike zeroth-order forecasting, which assumes the future will mirror the current state without considering the past rate of change, first-order forecasting integrates this rate into its predictions. This means, that instead of expecting the status quo to persist, first-order forecasting anticipates growth or decline based on past trends. This method acknowledges that developments, especially in fast-evolving fields like AI, often follow a trajectory that can inform future expectations. However, choosing between these forecasting methods depends on the specific context and the predictability of the trend in question.

Implementing First-Order Forecasting in AI. In practice, first-order forecasting for AI involves analyzing the historical progression of AI capabilities and technology improvements to forecast future advancements. For example, observing the development timeline and performance enhancements of AI models, such as the GPT series by OpenAI, provides a basis for predicting the release and capabilities of future iterations. Similarly, applying first-order forecasting to hardware advancements, guided by historical trends like Moore’s Law, allows for projections about the future computational power available for AI development.

Practical Examples and Methodology. One example of a first-order forecasting framework in AI is trend extrapolation using performance curves. This involves plotting the performance of AI systems against time or resources (like data or compute), fitting a curve to the data, and then extrapolating this curve into the future. This approach has been used to forecast trends in areas like image recognition, chess playing, and natural language processing.

Another example is looking at how quickly new versions of models like OpenAI’s GPT series are being developed and how much their performance is improving with each iteration. By extrapolating these trends, forecasters could make predictions about when we might see future versions of these models and how capable they are likely to be.

Yet another common approach in first-order forecasting is to analyze trends in hardware improvements, such as those predicted by Moore’s Law. Moore’s Law, which predicts that the number of transistors on a microchip doubles approximately every two years, has been a reliable trend in the computing industry for several decades. Forecasters might extrapolate this trend to make predictions about future developments in computing power, which are crucial for training increasingly powerful AI models.

First-Order Forecasts. Here are some forecasts for GPT-2030, by Jacob Steinhardt based on this first-order forecasting methodology. He used “empirical scaling laws, projections of future compute and data availability, the velocity of improvement on specific benchmarks, empirical inference speed of current systems, and potential future enhancements in parallelism. […]” (source) to predict these capabilities.

GPT-2030 will likely be superhuman at various specific tasks, including coding, hacking, and math […]

GPT-2030 can be run in parallel. The organization that trains GPT-2030 would have enough compute to run many parallel copies: I estimate enough to perform 1.8 million years of work when adjusted to human working speeds […]

GPT-2030’s copies can share knowledge due to having identical model weights, allowing for rapid parallel learning: I estimate 2,500 human-equivalent years of learning in 1 day.”

5.3: Biological Anchors Framework

What are Biological anchors? Biological anchors are a forecasting technique. To find a reference class, assume that the human brain is indicative of general intelligence. This means we can treat it as a proof of concept. Whatever “amount of compute” it takes to train a human being, might be roughly the same amount it should take to train a TAI. The biological anchors approach estimates the compute required for AI to reach a level of intelligence comparable to humans, outlined through several steps:

First, assess how much computation the human brain performs, translating this into a quantifiable measure similar to computer operations in FLOP/s.

Second, estimate the amount of computation needed to train a neural network to match the brain’s inferential capacity, adjusting for future improvements in algorithmic efficiency.

Third, examine when it would be feasible to afford such vast computational resources, taking into account the decreasing cost of compute, economic growth, and increasing investment in AI.

Finally, by analyzing these factors, we can predict when it might be economically viable for AI companies to deploy the necessary resources for developing TAI.

Determining the exact computational equivalent for the human brain’s training process is complex, leading to the proposal of six hypotheses, collectively referred to as “biological anchors” or “bioanchors.” Each anchor has a different weighting contributing to the overall prediction.

Evolution Anchor: Total computational effort across all evolutionary history.

Lifetime Anchor: Brain’s computational activity from birth to adulthood (0-32).

Neural Network and Genome Anchors: Various computational benchmarks based on the human brain and genome to gauge the scale of parameters needed for AI to achieve general intelligence.

Forecasting with Biological Anchors. By integrating these anchors with projections of future compute accessibility, we can outline a potential timeline for TAI. This method aims to provide a “soft upper bound” on TAI’s arrival rather than pinpointing an exact year, acknowledging the complexity and unpredictability of AI development. (source) The following image gives an overview of the methodology.

(source)

Evolution anchor. This anchor quantifies the computational effort invested by evolution in shaping the human brain. It considers the vast amount of processing and learning that has taken place from the emergence of the first neurons to the development of the modern human brain. This method suggests that evolution has served as a form of “pre-training” for the human brain, enhancing its ability to adapt and survive. To estimate the computational power of this evolutionary “pre-training”, the report considers the total amount of compute used by all animal brains over the course of evolution. This includes not just the brains of humans, but also those of our ancestors and other animals with nervous systems. The idea is that all of this brain activity represents a form of learning or adaptation that has contributed to the development of the modern human brain. While the exact calculations involved in this estimate are complex and subject to considerable uncertainty, the basic idea is to multiply the number of animals that have ever lived by the amount of compute each of their brains performed over their lifetimes. This gives an estimate of the total compute performed by all animal brains over the course of evolution.

(source)

Cotra accounts for these considerations and assumes that the “average ancestor” performed as many FLOP/s as a nematode, and that there were on average ~1e21 ancestors at any time. This yields a median of ~1e41 FLOP, which seems extraordinarily high compared to modern machine learning. As an example, Google’s PaLM model was trained with ~2.5e24 FLOP (17 orders of magnitude smaller). She gives this anchor a weight of 10%. (source)

Lifetime anchor. This refers to the total computational activity the human brain performs over a human lifetime. This anchor is essentially a measure of the “training” a human brain undergoes from birth to adulthood and incorporates factors such as the number of neurons in the human brain, the amount of computation each neuron performs per year, and the number of years it takes for a human to reach adulthood. The human brain has an estimated 86 billion neurons. Each of these neurons performs a certain number of computations per second, which can be calculated as a certain number of operations per second in FLOP/s. When calculating the total amount of compute over a lifetime, these factors are multiplied together, along with the number of years a human typically lives.