The inordinately slow spread of good AGI conversations in ML

Spencer Greenberg wrote on Twitter:

Recently @KerryLVaughan has been critiquing groups trying to build AGI, saying that by being aware of risks but still trying to make it, they’re recklessly putting the world in danger. I’m interested to hear your thought/reactions to what Kerry says and the fact he’s saying it.

Michael Page replied:

I’m pro the conversation. That said, I think the premise—that folks are aware of the risks—is wrong.

[...]

Honestly, I think the case for the risks hasn’t been that clearly laid out. The conversation among EA-types typically takes that as a starting point for their analysis. The burden for the we’re-all-going-to-die-if-we-build-x argument is—and I think correctly so—quite high.

Oliver Habryka then replied:

I find myself skeptical of this.

[...]

Like, my sense is that it’s just really hard to convince someone that their job is net-negative. “It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends on his not understanding it” And this barrier is very hard to overcome with just better argumentation.

My reply:

I disagree with “the case for the risks hasn’t been that clearly laid out”. I think there’s a giant, almost overwhelming pile of intro resources at this point, any one of which is more than sufficient, written in all manner of style, for all manner of audience.[1]

(I do think it’s possible to create a much better intro resource than any that exist today, but ‘we can do much better’ is compatible with ‘it’s shocking that the existing material hasn’t already finished the job’.)

I also disagree with “The burden for the we’re-all-going-to-die-if-we-build-x argument is—and I think correctly so—quite high.”

If you’re building a machine, you should have an at least somewhat lower burden of proof for more serious risks. It’s your responsibility to check your own work to some degree, and not impose lots of micromorts on everyone else through negligence.[2]

But I don’t think the latter point matters much, since the ‘AGI is dangerous’ argument easily meets higher burdens of proof as well.

I do think a lot of people haven’t heard the argument in any detail, and the main focus should be on trying to signal-boost the arguments and facilitate conversations, rather than assuming that everyone has heard the basics.

A lot of the field is very smart people who are stuck in circa-1995 levels of discourse about AGI.

I think ‘my salary depends on not understanding it’ is only a small part of the story. ML people could in principle talk way more about AGI, and understand the problem way better, without coming anywhere close to quitting their job. The level of discourse is by and large too low for ‘I might have to leave my job’ to be the very next obstacle on the path.

Also, many ML people have other awesome job options, have goals in the field other than pure salary maximization, etc.

More of the story: Info about AGI propagates too slowly through the field, because when one ML person updates, they usually don’t loudly share their update with all their peers. This is because:

1. AGI sounds weird, and they don’t want to sound like a weird outsider.

2. Their peers and the community as a whole might perceive this information as an attack on the field, an attempt to lower its status, etc.

3. Tech forecasting, differential technological development, long-term steering, exploratory engineering, ‘not doing certain research because of its long-term social impact’, prosocial research closure, etc. are very novel and foreign to most scientists.

EAs exert effort to try to dig up precedents like Asilomar partly because Asilomar is so unusual compared to the norms and practices of the vast majority of science. Scientists generally don’t think in these terms at all, especially in advance of any major disasters their field causes.

And the scientists who do find any of this intuitive often feel vaguely nervous, alone, and adrift when they talk about it. On a gut level, they see that they have no institutional home and no super-widely-shared ‘this is a virtuous and respectable way to do science’ narrative.

Normal science is not Bayesian, is not agentic, is not ‘a place where you’re supposed to do arbitrary things just because you heard an argument that makes sense’. Normal science is a specific collection of scripts, customs, and established protocols.

In trying to move the field toward ‘doing the thing that just makes sense’, even though it’s about a weird topic (AGI), and even though the prescribed response is also weird (closure, differential tech development, etc.), and even though the arguments in support are weird (where’s the experimental data??), we’re inherently fighting our way upstream, against the current.

Success is possible, but way, way more dakka is needed, and IMO it’s easy to understand why we haven’t succeeded more.

This is also part of why I’ve increasingly updated toward a strategy of “let’s all be way too blunt and candid about our AGI-related thoughts”.

The core problem we face isn’t ‘people informedly disagree’, ‘there’s a values conflict’, ‘we haven’t written up the arguments’, ‘nobody has seen the arguments’, or even ‘self-deception’ or ‘self-serving bias’.

The core problem we face is ‘not enough information is transmitting fast enough, because people feel nervous about whether their private thoughts are in the Overton window’.

We need to throw a brick through the Overton window. Both by adopting a very general policy of candidly stating what’s in our head, and by propagating the arguments and info a lot further than we have in the past. If you want to normalize weird stuff fast, you have to be weird.

What broke the silence about artificial general intelligence (AGI) in 2014 wasn’t Stephen Hawking writing a careful, well-considered essay about how this was a real issue. The silence only broke when Elon Musk tweeted about Nick Bostrom’s Superintelligence, and then made an off-the-cuff remark about how AGI was “summoning the demon.”

Why did that heave a rock through the Overton window, when Stephen Hawking couldn’t? Because Stephen Hawking sounded like he was trying hard to appear sober and serious, which signals that this is a subject you have to be careful not to gaffe about. And then Elon Musk was like, “Whoa, look at that apocalypse over there!!” After which there was the equivalent of journalists trying to pile on, shouting, “A gaffe! A gaffe! A… gaffe?” and finding out that, in light of recent news stories about AI and in light of Elon Musk’s good reputation, people weren’t backing them up on that gaffe thing.

Similarly, to heave a rock through the Overton window on the War on Drugs, what you need is not state propositions (although those do help) or articles in The Economist. What you need is for some “serious” politician to say, “This is dumb,” and for the journalists to pile on shouting, “A gaffe! A gaffe… a gaffe?” But it’s a grave personal risk for a politician to test whether the public atmosphere has changed enough, and even if it worked, they’d capture very little of the human benefit for themselves.

Simone Sturniolo commented on “AGI sounds weird, and they don’t want to sound like a weird outsider.”:

I think this is really the main thing. It sounds too sci-fi a worry. The “sensible, rational” viewpoint is that AI will never be that smart because haha, they get funny word wrong (never mind that they’ve grown to a point that would have looked like sorcery 30 years ago).

To which I reply: That’s an example of a more-normal view that exists in society-at-large, but it’s also a view that makes AI research sound lame. (In addition to being harder to say with a straight face if you’ve been working in ML for long at all.)

There’s an important tension in ML between “play up AI so my work sounds important and impactful (and because it’s in fact true)”, and “downplay AI in order to sound serious and respectable”.

This is a genuine tension, with no way out. There legit isn’t any way to speak accurately and concretely about the future of AI without sounding like a sci-fi weirdo. So the field ends up tangled in ever-deeper knots motivatedly searching for some third option that doesn’t exist.

Currently popular strategies include:

1. Quietism and directing your attention elsewhere.

2. Derailing all conversations about the future of AI to talk about semantics (“‘AGI’ is a wrong label”).

3. Only talking about AI’s long-term impact in extremely vague terms, and motivatedly focusing on normal goals like “cure cancer” since that’s a normal-sounding thing doctors are already trying to do.

(Avoid any weird specifics about how you might go about curing cancer, and avoid weird specifics about the social effects of automating medicine, curing all disease, etc. Concreteness is the enemy.)

4. Say that AI’s huge impacts will happen someday, in the indefinite future. But that’s a “someday” problem, not a “soon” problem.

(Don’t, of course, give specific years or talk about probability distributions over future tech developments, future milestones you expect to see 30 years before AGI, cruxes, etc. That’s a weird thing for a scientist to do.)

5. Say that AI’s impacts will happen gradually, over many years. Sure, they’ll ratchet up to being a big thing, but it’s not like any crazy developments will happen overnight; this isn’t science fiction, after all.

(Somehow “does this happen in sci-fi?” feels to people like a relevant source of info about the future.)

When Paul Christiano talks about soft takeoff, he has in mind a scenario like ‘we’ll have some years of slow ratcheting to do some preparation, but things will accelerate faster and faster and be extremely crazy and fast in the endgame’.

But what people outside EA usually have in mind by soft takeoff is:

I think the Paul scenario is one where things start going crazy in the next few decades, and go more and more crazy, and are apocalyptically crazy in thirty years or so?

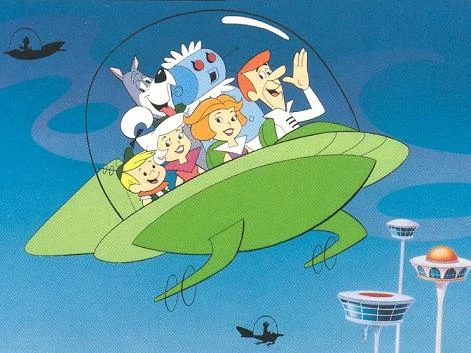

But what many ML people seemingly want to believe (or want to talk as though they believe) is a Jetsons world.

A world where we gradually ratchet up to “human-level AI” over the next 50–250 years, and then we spend another 50–250 years slowly ratcheting up to crazy superhuman systems.

The clearest place I’ve seen this perspective explicitly argued for is in Rodney Brooks’ writing. But the much more common position isn’t to explicitly argue for this view, or even to explicitly state it. It jut sort of lurks in the background, like an obvious sane-and-moderate Default. Even though it immediately and obviously falls apart as a scenario as soon as you start poking at it and actually discussing the details.

6. Just say it’s not your job to think or talk about the future. You’re a scientist! Scientists don’t think about the future. They just do their research.

7. More strongly, you can say that it’s irresponsible speculation to even broach the subject! What a silly thing to discuss!

Note that the argument here usually isn’t “AGI is clearly at least 100 years away for reasons X, Y, and Z; therefore it’s irresponsible speculation to discuss this until we’re, like, 80 years into the future.” Rather, even giving arguments for why AGI is 100+ years away is assumed at the outset to be irresponsible speculation. There isn’t a cost-benefit analysis being given here for why this is low-importance; there’s just a miasma of unrespectability.

- ^

Some of my favorite informal ones to link to: Russell 2014; Urban 2015 (w/ Muehlhauser 2015); Yudkowsky 2016a; Yudkowsky 2017; Piper 2018; Soares 2022

Some of my favorite less-informal ones: Bostrom 2014a; Bostrom 2014b; Yudkowsky 2016b; Soares 2017; Hubinger et al. 2019; Ngo 2020; Cotra 2021; Yudkowsky 2022; Arbital’s listing

Other good ones include: Omohundro 2008; Yudkowsky 2008; Yudkowsky 2011; Muehlhauser 2013; Yudkowsky 2013; Armstrong 2014; Dewey 2014; Krakovna 2015; Open Philanthropy 2015; Russell 2015; Soares 2015a; Soares 2015b; Steinhardt 2015; Alexander 2016; Amodei et al. 2016; Open Philanthropy 2016; Taylor et. al 2016; Taylor 2017; Wiblin 2017; Yudkowsky 2017; Garrabrant and Demski 2018; Harris and Yudkowsky 2018; Christiano 2019a; Christiano 2019b; Piper 2019; Russell 2019; Shlegeris 2020; Carlsmith 2021; Dewey 2021; Miles 2021; Turner 2021; Steinhardt 2022

- ^

Or, I should say, a lower “burden of inquiry”.

You should (at least somewhat more readily) take the claim seriously and investigate it in this case. But you shouldn’t require less evidence to believe anything — that would just be biasing yourself, unless you’re already biased and are trying to debias yourself. (In which case this strikes me as a bad debiasing tool.)

See also the idea of “conservative futurism” versus “conservative engineering” in Creating Friendly AI 1.0:

The conservative assumption according to futurism is not necessarily the “conservative” assumption in Friendly AI. Often, the two are diametric opposites. When building a toll bridge, the conservative revenue assumption is that half as many people will drive through as expected. The conservative engineering assumption is that ten times as many people as expected will drive over, and that most of them will be driving fifteen-ton trucks.

Given a choice between discussing a human-dependent traffic-control AI and discussing an AI with independent strong nanotechnology, we should be biased towards assuming the more powerful and independent AI. An AI that remains Friendly when armed with strong nanotechnology is likely to be Friendly if placed in charge of traffic control, but perhaps not the other way around. (A minivan can drive over a bridge designed for armor-plated tanks, but not vice-versa.

The core argument for hard takeoff, ‘AI can achieve strong nanotech’, and “get it right the first time” is that they’re true, not that they’re “conservative”. But it’s of course also true that a sane world that thought hard takeoff were “merely” 20% likely, would not immediately give up and write off human survival in those worlds. Your plan doesn’t need to survive one-in-a-million possibilities, but it should survive one-in-five ones!

- The basic reasons I expect AGI ruin by (18 Apr 2023 3:37 UTC; 186 points)

- Four mindset disagreements behind existential risk disagreements in ML by (11 Apr 2023 4:53 UTC; 136 points)

- AGI ruin mostly rests on strong claims about alignment and deployment, not about society by (24 Apr 2023 13:06 UTC; 70 points)

- Four mindset disagreements behind existential risk disagreements in ML by (EA Forum; 11 Apr 2023 4:53 UTC; 61 points)

- The basic reasons I expect AGI ruin by (EA Forum; 18 Apr 2023 3:37 UTC; 58 points)

- Reframing the AI Risk by (1 Jul 2022 18:44 UTC; 26 points)

- 's comment on Pivotal outcomes and pivotal processes by (EA Forum; 22 Jun 2022 10:24 UTC; 20 points)

- 's comment on The inordinately slow spread of good AGI conversations in ML by (21 Jun 2022 19:41 UTC; 19 points)

- 's comment on Pivotal outcomes and pivotal processes by (22 Jun 2022 10:24 UTC; 18 points)

- AGI ruin mostly rests on strong claims about alignment and deployment, not about society by (EA Forum; 24 Apr 2023 13:07 UTC; 16 points)

- 's comment on Most experts believe COVID-19 was probably not a lab leak by (2 Feb 2024 22:16 UTC; 15 points)

- 's comment on My highly personal skepticism braindump on existential risk from artificial intelligence. by (EA Forum; 31 Jan 2023 6:44 UTC; 11 points)

- 's comment on Alexander Gietelink Oldenziel’s Shortform by (19 Nov 2024 19:26 UTC; 9 points)

tl;dr: most AI/ML practitioners make moral decisions based on social feedback rather than systems of moral thought. Good arguments don’t do much here.

Engineers and scientists, most of the time, do not want to think about ethics in the context of their work, and begrudgingly do so to the extent that they are socially rewarded for it (and socially punished for avoiding it). See here.

I wrote in another comment about my experience in my early research career at a FAANG AI lab trying to talk to colleagues about larger scale risks. Granted we weren’t working on anything much like AGI at the time in that group, but there are some overlapping themes here.

What I built to in that story was that bringing up anything about AGI safety in even a work-adjacent context (i.e. not a meeting about a thing, but, say, over lunch) was a faux pas:

I’m connecting this in particular to point 6 in your second list (“that’s not my job”).

David Chapman writes, in a fairly offhand footnote in Vividness, with reference to stages in Kegan’s constructive developmental framework:[1]

I think this is a useful map, if a bit uncharitable, where morality and politics go in the “emotional and relational domains” bucket. Go hang out at Brain or FAIR, especially the parts farther away from AGI conversations, especially among IC-level scientists and engineers, and talk to people about anything controversial. Unless you happen across someone’s special interest and they have a lot to say about shipping logistics in Ukraine or something, you’re generally going to encounter more or less the same views that you would expect to find on Twitter (with some neoliberal-flavored cope about the fact that FAANG employees are rich; see below). Everyone will get very excited to go participate in a protest on Google campus about hiring diversity or pay inequality or someone’s toxic speech who needs to be fired, because they are socially embedded in a community in which these are Things That Matter.

You look into what “AI ethics” means to most practitioners and generally the same pattern emerges: people who work on AI are very technically proficient at working on problems around fairness and accountability and so on. The step of actually determining which ethical problems they should be responsible for is messier, is what I think Rob’s post is primarily about, and I think is better understood using Chapman’s statement about technical folks operating at stage 3 outside of technical contexts.

Here’s some fresh AI ethics controversy: Percy Liang’s censure of Yannic Kilcher for his GPT-4chan project. From the linked form, (which is an open letter soliciting more people signing on and boasting an all-star cast after being up for 24 hours), emphasis mine:

You may feel one way or another about this; personally if I put bigger AI safety questions aside and think about this I feel ambivalent, unsure, kind of icky about it.

But my point here is not to debate the merits of this open letter. My point is that this is what the field connects to as their own moral responsibility. Problems that their broader community already cares about for non-technical and social-signaling-y reasons, but that their technical work undeniably affects. I don’t see this even as moral misalignment in the most obvious sense, rather that engineers and scientists, most of the time, do not want to think about ethics in the context of their work, and begrudgingly do so to the extent that they are socially rewarded for it (and socially punished for avoiding it).

In trying to reach these folks, convincing arguments are a type error. Convincing arguments require systematic analysis, a framework for analyzing moral impact, which the vast majority of people, even many successful scientists and engineers, don’t really use to make decisions. Convincing arguments are for setting hyperparameters and designing your stack and proving that your work counts as “responsible AI” according to the current consensus on what that requires. Social feedback is the source of an abstract moral issue attaining “responsible AI” status, actually moving that consensus around.

I spent some years somewhat on the outside, not participating in the conversation, but seeing it bleed out into the world. Seeing what that looks like from a perspective like what I’m describing. Seeing how my friends, the ones I made during my time away from the Bay Area and effective altruism and AI alignment, experienced it. There’s a pervasive feeling that the world is dominated by “a handful of bug-eyed salamanders in Silicon Valley” and their obsessions with living forever and singularity myths and it’s a tragic waste of resources that could be going to helping real people with real problems. Even this description is uncharacteristically charitable.

This is not the perspective of a Google engineer, of course. But I think that this narrative has a much stronger pull to a typical Google engineer than any alignment argument. “You’re culpable as part of the Big Evil Capitalist Machine that hurts minorities” is more memetically powerful than “A cognitive system with sufficiently high cognitive powers, given any medium-bandwidth channel of causal influence, will not find it difficult to bootstrap to overpowering capabilities independent of human infrastructure.” This is probably counterintuitive in the frame of a conversation on LessWrong. I think it’s right.

There’s a pithy potential ending to this comment that keeps jumping into my mind. It feels like both an obviously correct strategic suggestion and an artistically satisfying bow to tie. Problem is it’s a pretty unpopular idea both among the populations I’m describing here and, I think, on LessWrong. So I’m gonna just not say it, because I don’t have enough social capital here at time of writing to feel comfortable taking that gambit.

I’d love it if someone else said it. If no one does, and I acquire sufficient social capital, maybe then I will.

Stage 3 is characterized by a sense of self and view being socially determined, whereas in stage 4 they are determined by the workings of some system (e.g. ~LW rationality; think “if I say something dumb people will think less of me” as stage 3 relating to rationality as community norms, versus “I think that preferring this route to more traditional policy influence requires extreme confidence about details of the policy situation” as stage 4 usage of the systems of thought prescribed by the framework).

Is the ending suggestion “take over the world / a large country”? Pure curiosity, since Leverage Research seems to have wanted to do that but… they seem to have been poorly-run, to understate.

Nothing like taking over the world. From a certain angle it’s almost opposite to that, relinquishing some control.

The observations in my long comment suggest to me some different angles for how to talk about alignment risk. They are part of a style of discourse that is not well-respected on LessWrong, and this being a space where that is pushed out is probably good for the health of LessWrong. But the state of broader popular political/ethical discourse puts a lot of weight on these types of arguments, and they’re more effective (because they push around so much social capital) at convincing engineers they have an external responsibility.

I don’t want to be too specific with the arguments unless I pull the trigger on writing something longer form. I was being a little cheeky at the end of that comment and since I posted it I’ve been convinced that there’s more harm in expressing that idea ineffectively or dismissively than I’d originally estimated (so I’m grateful to the social mechanism that prevented me from causing harm there!).

A success story would look like building a memeplex that is entirely truthful, even if it’s distasteful to rationalists, and putting it out into the world, where it would elevate alignment to the status that fairness/accountability have in the ML community. This would be ideologically decentralizing to the field; in this success story I don’t expect the aesthetics of LessWrong, Alignment Forum, etc to be an adequate home for this new audience, and I would predict something that sounds more like that link from Percy Liang becoming the center of the conversation. It would be a fun piece of trivia that this came from the rationalist community, and look at all this other crazy stuff they said! We might hear big names in AI say of Yudkowsky what Wittgenstein said of Russell:

This may be scary because it means the field would be less aligned than it is currently. My instinct says this is a kind of misalignment that we’re already robust to: ideological beliefs in other scientific communities are often far more heterogeneous than those of the AI alignment community. It may be scary because the field would become more political, which may end up lowering effectiveness, contra my hypothesis that growing the field this way would be effective. It may be scary because it’s intensely status-lowering in some contexts for anyone who would be reading this.

I’m still on the fence for whether this would be good on net. Every time I see a post about the alignment discourse among broader populations, I interpret it as people interested in having some of this conversation, and I’ll keep probing.

EDIT: retracted in this context, see reply.

So… growing alignment by… merging it with far-less-important political issues… and being explicitly culture-war-y about it? Is the endgame getting non-right-wing politicians to regulate AGI development?Because… for [structural](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_Electoral_College) [reasons](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gerrymandering), one side has an advantage in many culture war battles, despite being a minority of citizens at the national level. (Within a state, either"side" could have the advantage, but whichever one has the advantage, tends to keep it for a while).̶Turning AGI safety into a culture war thing is a bad idea, since [culture war things don’t seem get much actual progress in Congress](https://www.slowboring.com/p/the-rise-and-importance-of-secret), and when they ̶do̶ it’s often something bad (see <s>"

;structural reasons" above).If this was your idea, I guess I’m glad you didn’t post it, but I also think you should think harder over whether it is, in fact, actually a good idea. Upvoted to commend your honesty though (glad 2-axis voting is on now).TLDR: P(culture war win& it’s in favor of regulation) + P(cww& it’s anti-regulation) + P(culture war loss) ≈ 1, and the first term is, by a quick reading of politics, outweighed by the combination of the other 2 terms.This is a bit of an odd time to start debating, because I haven’t explicitly stated a position, and it seems we’re in agreement that that’s a good thing[1]. Calling this to attention because

You make good points.

The idea you’re disagreeing with digresses from any idea I would endorse multiple times in the first two sentences.

Speaking first to this point about culture wars: that all makes sense to me. By this argument, “trying to elevate something to being regulated by congress by turning it into a culture war is not a reliable strategy” is probably a solid heuristic.

I wonder whether we’ve lost the context of my top-level comment. The scope (the “endgame”) I’m speaking to is moving alignment into the set of technical safety issues that the broader ML field recognizes as its responsibility, as has happened with fairness. My main argument is that a typical ML scientist/engineer tends not to use systemic thought to adjudicate which moral issues are important, and this is instead “regulated by tribal circuitry” (to quote romeostevensit’s comment). This does not preclude their having requisite technical ability to make progress on the problem if they decide it’s important.

As far as strategic ideas, it gets hairy from there. Again, I think we’re in agreement that it’s good for me not to come out here with a half-baked suggestion[1].

–––

There’s a smaller culture war, a gray-vs-blue one, that’s been waging for quite some time now, in which more inflamed people argue about punching nazis and more reserved people argue about what’s more important between protecting specific marginalized groups or protecting discussion norms and standards of truth.

Here’s a hypothetical question that should bear on strategic planning: suppose you could triple the proportion of capable ML researchers who consider alignment to be their responsibility as an ML researcher, but all of the new population are on the blue side of zero on the protect-groups-vs-protect-norms debate. Is this an outcome more likely to save everyone?

On the plus side, the narrative will have shifted massively away from a bunch of the failure modes Rob identified in the post (this is by assumption: “consider alignment to be their responsibility”).

On the minus side, if you believe that LW/AF/EA-style beliefs/norms/aesthetics/ethics are key to making good progress on the technical problems, you might be concerned about alignment researchers of a less effective style competing for resources.

If no, is there some other number of people who could be convinced in this manner such that you would expect it to be positive on AGI outcomes?

To reiterate:

I expect a large portion of the audience here would dislike my ideas about this for reasons that are not helpful.

I expect it to be a bad look externally for it to be discussed carelessly on LW.

I’m not currently convinced it’s a good idea, and for reasons 1 and 2 I’m mostly deliberating it elsewhere.

Ah, thank you for clarification!

Allying AI safety with DEI LGBTQIA+ activism won’t do any favors to AI safety. Nor do I think it’s a really novel idea. Effective Altruism occasionally flirts with DEI and other people have suggested using similar tactics to get AI safety in the eyes of modern politics.

AI researchers are already linking AI safety with DEI with the effect of limiting the appearance of risk. If someone was to read a ‘risks’ section on an OpenAI paper they would come away with the impression that the biggest risk of AI is that someone could use it to make a misleading photo of a politician or that the AI might think flight attendants are more likely to be women than men! Their risks section on Dalle-2 reads:

The point being, DEI does not take up newcomers and lend its support to their issues. It subsumes real issues and funnels efforts directed to solve them towards the DEI wrecking ball.

I believe many people interpret claims that they might be causing harm as a social attack and not about causal reality.

Currently the burden of proof is on those who claim danger, while we would prefer the burden of proof to be on those who claim safety. Burden of proof moves are regulated by tribal circuitry IME.

Another reason the broader ML field may be reluctant to discuss AGI is a cultural shift in the field that happened after the AI winters. I’m quoting part of A Bird’s Eye View of the ML Field [Pragmatic AI Safety #2] where I first saw this idea:

Anyway, I think your post (“The inordinately slow spread...”) is good. Figuring out how to get the broader ML community to talk more explicitly about AGI and care more about AGI x-risk would be a huge win.

I’m confused. Aren’t the organizations pushing hardest to build AGI (OpenAI, DeepMind, Anthropic) led or founded by people who were among the earliest to be convinced of AI risk? Ah, found some additional context in the Twitter thread.

Kerry Vaughan:

Michael Page:

So, apparently the people who started OpenAI to reduce AI risk, failed to make sure that the people they hired to build AGI are actually convinced of AI risk?!

I could imagine that OpenAI getting top talent to ensure their level of research achievements while also filtering people they hire by their seriousness about reducing civilization-level risks is too hard. Or at least it could easily have been infeasible 4 years ago.

I know a couple of people at DeepMind and none of them have reducing civilization-level risks as one of their primary motivations for working there, as I believe is the case with most of DeepMind.

The original stated rationale behind OpenAI was https://www.wired.com/2015/12/how-elon-musk-and-y-combinator-plan-to-stop-computers-from-taking-over/. I gather that another big rationale behind OpenAI was ‘Elon was scared of Demis doing bad things with AGI’; and another big rationale was ‘Sam was already interested in doing cool stuff with AI regardless of the whole AI-risk thing’. (Let me know if you think any of this summary is misleading or wrong.)

Since then, Elon has left, and Sam and various other individuals at OpenAI seem to have improved their models of AGI risk a lot. But this does seem like a very different situation than ‘founding an org based on an at-all good understanding of AI risk, filtering for staff based on such an understanding, etc.’

This link is dead for me. I found this link that points to the same article.

Thanks! Edited.

I think one thing is that they had a different idea of what AI risk entails.

What idea would that be, misuse risks rather than misalignment risks?

UPDATE: I did mean this comment as a genuine question, not a rhetorical one. I’m actually curious about what underlies these perceptions of OpenAI. Feel free to private message me if you’d prefer not to reply in public. Another possible reason that occurred to me after posting this comment is that OpenAI was the first serious competitor to DeepMind in pursuing AGI, so people may resent them making AGI research more competitive and hence arguably creating pressure to rush decisions and cut corners on safety.

Why do so many people on LessWrong say that OpenAI doesn’t prioritize AI x-risk?

I’m not saying that they definitely do. But since they were founded with AI risks in mind and have had some great safety researchers over the years, I am curious which events lead people to frequently say that they are not prioritizing it. I know a lot of their safety researchers left at one point, which is a bad sign about their safety prioritization, but not conclusive.

I get the sense a lot of people were upset when they changed from a non-profit to a capped-profit structure. But that doesn’t say anything directly about how they prioritize x-risk, and the fact that they didn’t go to a 100% for-profit structure shows they are at least prioritizing misuse risks.

OpenAI has had at least a few safety-related publications since 2020:

https://openai.com/blog/language-model-safety-and-misuse/

https://openai.com/blog/summarizing-books/

https://openai.com/blog/learning-to-summarize-with-human-feedback/

https://openai.com/blog/microscope/

The claim that AI capabilities research is bad for Alignment is non-obvious.

In particular, if you think of AI-Alignment as a race between knowledge and hardware (more knowledge makes aligning AI easier, more hardware makes building dangerous AI easier), then AI research (that isn’t purely building faster hardware) is net-positive.

I have never thought of such a race. I think this comment is worth its own post.

The link is the post where I recently encountered the idea.

My sense is that the existing arguments are not very strong (e.g. I do not find them convincing), and their pretty wide acceptance in EA discussions mostly reflects self-selection (people who are convinced that AI risk is a big problem are more interested in discussing AI risk). So in that sense better intro documents would be nice. But maybe there simply aren’t stronger arguments available? (I personally would like to see more arguments from an “engineering” perspective, starting from current computer systems rather than from humans or thought experiments). I’d be curious what fraction of e.g. random ML people find current intro resources persuasive.

That said, just trying to expose more people to the arguments makes a lot of sense; however convincing the case is, the number of convinced people should scale linearly with the number of exposed people. And social proof dynamics probably make it scale super-linearly.

I’d be curious to hear whether you disagree with Gwern’s https://www.gwern.net/Tool-AI.

I agree with it but I don’t think it’s making very strong claims.

I mostly agree with part 1; just giving advice seems too restrictive. But there’s a lot of ground between “only gives advice” and “fully autonomous” and “fully autonomous” and “globally optimizing a utility function”, and I basically expect a smooth increase in AI autonomy over time as they are proved capable and safe. I work in HFT; I think that industry has some of the most autonomous AIs deployed today (although not that sophisticated), but they’re very constrained over what actions they can take.

I don’t really have the expertise to have an opinion on “agentiness helps with training”. That sounds plausible to me. But again, “you can pick training examples” is very far from “fully autonomous”. I think there’s a lot of scope for introducing “taking actions” that doesn’t really pose a safety risk (and ~all of Gwern’s examples fall into that, I think; eg optimizing over NN hyper parameters doesn’t seem scary).

I guess overall I agree AIs will take a bunch of actions, but I’m optimistic about constraining the action space or the domain/world-model in a way that IMO gets you a lot of safety (in a way that is not well-captured by speculating about what the right utility function is).

I suspect your industry is a special case, in that you can get away with automating everything with purely narrow AI. But in more complicated domains, I worry that constraints would not be able to be specified well, especially for things like AI managing.

Great post. I also fear that it may not be socially acceptable for AI researchers to talk about the long-term effects of AI despite the fact that, because of exponential progress, most of the impact of AI will probably occur in the long term.

I think it’s important that AI safety and considerations related to AGI become mainstream in the field of AI because it could be dangerous if the people building AGI are not safety-conscious.

I want a world where the people building AGI are also safety researchers rather than one where the AI researchers aren’t thinking about safety and the safety people are shouting over the wall and asking them to build safe AI.

This idea reminds me of how software development and operations were combined into the DevOps role in software companies.

I’m a little sheepish about trying to make a useful contribution to this discussion without spending a lot of time thinking things through but I’ll give it a go anyway. There’s a fair amount that I agree with here, including that there is by now a lot of introductory resources. But regarding the following:

I feel like I want to ask: Do you really find it “shocking”? My experience with explaining things to more general audiences leaves me very much of the opinion that it is by default an incredibly slow and difficult process to get unusual, philosophical, mathematical, or especially technical ideas to permeate. I include ‘average ML engineer’ as something like a “more general audience” member relative to MIRI style AGI Alignment theory. I guess I haven’t thought it about it much but presumably there exist ideas/arguments that are way more mainstream, also very important, and with way more written about them that people still somehow, broadly speaking, don’t engage with or understand?

I also don’t really understand how the point that is being made in the quote from Inadequate Equilibria is supposed to work. Perhaps in the book more evidence is provided for when “the silence broke”, but the Hawking article was before the release of Superintelligencea and then the Musk tweet was after it and was reacting to it(!) .. So I guess I’m sticking up for AGI x-risk respectability politics a bit here because surely I might also use essentially this same anecdote to support the idea that boring old long-form academic writing that clearly lays things out in as rigorous a way as possible is actually more the root cause that moved the needle here? Even if it ultimately took the engagement of Musk’s off the cuff tweets, Gates, or journalists etc., they wouldn’t have had something respectable enough to bounce off had Bostrom not given them the book.

No need to be sheepish, IMO. :) Welcome to the conversation!

I think it’s the largest mistake humanity has ever made, and I think it implies a lower level of seriousness than the seriousness humanity applied to nuclear weapons, asteroids, climate change, and a number of other risks in the 20th-century. So I think it calls for some special explanation beyond ‘this is how humanity always handles everything’.

I do buy the explanations I listed in the OP (and other, complementary explanations, like the ones in Inadequate Equilbria), and I think they’re sufficient to ~fully make sense of what’s going on. So I don’t feel confused about the situation anymore. By “shocking” I meant something more like “calls for an explanation”, not “calls for an explanation, and I don’t have an explanation that feels adequate”. (With added overtones of “horrifying”.)

As someone who was working at MIRI in 2014 and watched events unfolding, I think the Hawking article had a negligible impact and the Musk stuff had a huge impact. Eliezer might be wrong about why Hawking had so little impact, but I do think it didn’t do much.

Thanks for the nice reply.

Yeah, OK, I think that helps clarify things for me.

Maybe we’re misunderstanding each other here. I don’t really doubt what you’re saying there^ i.e. I am fully willing to believe that the Hawking thing had negligible impact and the Musk tweet had a lot. I’m more pointing to why Musk had a lot rather than why Hawking had little: Trying to point out that since Musk was reacting to Superintelligence, one might ask whether he could have had a similar impact without Superintelligence. And so maybe the anecdote could be used as evidence that Superintelligence was really the thing that helped ‘break the silence’. However, Superintelligence feels way less like “being blunt” and “throwing a brick” and—at least from the outside—looks way more like the “scripts, customs, and established protocols” of “normal science” (i.e. Oxford philosophy professor writes book with somewhat tricky ideas in it, published by OUP, reviewed by the NYT etc. etc.) and clearly is an attempt to make unusual ideas sound “sober and serious”. So I’m kind of saying that maybe the story doesn’t necessarily argue against the possibility of doing further work like that that—i.e. writing books that manage to stay respectable and manage to “speak accurately and concretely about the future of AI without sounding like a sci-fi weirdo”(?)

Oh, I do think Superintelligence was extremely important.

I think Superintelligence has an academic tone (and, e.g., hedges a lot), but its actual contents are almost maximally sci-fi weirdo—the vast majority of public AI risk discussion today, especially when it comes to intro resources, is much less willing to blithely discuss crazy sci-fi scenarios.

Overall, I think that Superintelligence’s success is some evidence against the Elon Musk strategy, but it’s weaker evidence inasmuch as it was still a super weird book that mostly ignores the Overton window and just talks about arbitrarily crazy stuff, rather than being as trying-to-be-normal as most other intro resources.

(E.g., “Most Important Century” is a lot weirder than most intro sources, but is still trying a lot harder than Superintelligence to sound normal. I’d say that Stuart Russell’s stuff and “Risks from Learned Optimization” are mostly trying a lot harder to sound normal than that, and “Concrete Problems” is trying harder still.)

(Re my comparison of “Most Important Century” and Superintelligence: I’d say this is true on net, but not true in all respects. “Most Important Century” is trying to be a much more informal, non-academic document than Superintelligence, which I think allows it to be candid and explicit in some ways Superintelligence isn’t.)

A better example than the Asilomar conference was the He Jiankui response. Scientists had strong norms against such research, and he went to jail for genetically engineering humanity for 3 years. That was a stronger response to perceived ethical violations than is the norm in science.

The two images in this post don’t load for me. As I understand it, they’re embedded here from Twitter’s content delivery network (CDN), and such embedded images don’t always load. To avert problems like this, it’s better to copy images in such a way that they’re hosted on LW’s own CDN instead.

Thanks, fixed!

The concern with the wider community AI scientists, in general, seems pretty naive. It’s far more likely and more reasonable to assume a smaller, vocal group with a vested interest in minimizing any criticism of AI, regardless of what form it takes and where it comes from. Making people compulsively self-censor is a classic tactic for that sort of thing.

Nice read. One thing that stood out to me was your claim that “Jetsons” AI (human level in 50-250 years, beyond later) was a riddiculous scenario. Perahps you can elaborate on why this scenario seems farfetched to you? (A lot of course hinges on the exact meaning of “human level”.)

I think Holden’s The Most Important Century sequence is probably the best reading here, with This Can’t Go On being the post most directly responding to your question (but I think it’ll make more sense if you read the whole thing.

(Really I think most of Lesswrong’s corpus is aiming to answer this question, with many different posts tackling it from different directions. I don’t know if there’s a single post specifically arguing that Jetsons world is silly, but lots of posts pointing at different intuitions that feed into the question. Superintelligence FAQ is relevant. Tim Urban’s The Artificial Intelligence Revolution is also relevant).

The two short answers are:

Even if you somehow get AI to human level and stop, you’d still have a whole new species that was capable of duplicating themselves, which would radically change how the world works.

It’s really unlikely for us to get to human level and then stop, given that that’s not generally how most progress works, not how the evolution of intelligence worked in the biological world, and not how our progress in AI has worked in many subdomains so far.

Also capable of doing AI research themselves. It would be incredibly strange if automating AI research didn’t accelerate AI research.

Well, evolution did “stop” at human-level intelligence!

I would add that “human-level intelligence” is just a very specific level to be at. Cf. “bald-eagle-level carrying capacity”; on priors you wouldn’t expect airplanes to exactly hit that narrow target out of the full range of physically possible carrying capacities.

This applies to the AI x-safety community as well.

I have noticed a lot of difficulties myself in trying to convey new arguments to others, and those arguments are clearly outside the community’s Overton window.

In my case, I am not hesitant to reach out to people and have conversations. Like, if you are up for seriously listening, I am glad to have a call for an hour.

Two key bottlenecks seem to have been:

Busy and non-self-motivated:

Most people are busily pursuing their own research or field-building projects.

They lack the bandwidth, patience or willingness to be disoriented about new arguments for a while, even if information value is high on a tiny prior probability of those arguments being true. Ie. when I say that these are arguments for why any (superficial) implementation of AGI-alignment would be impossible (to maintain over the long run).

Easily misinterpreted:

In my one-on-one calls so far, researchers almost immediately clicked the terms and arguments I mentioned into their existing conceptual frameworks of alignment. Which I get, because those researchers incline toward and trained themselves to think like theoretical physicists, mathematicians or software engineers – not like linguistic anthropologists.

But the inferential gap is large, and I cannot convey how large without first conveying the arguments. People like to hold on to their own opinions and intuitions, or onto their general-not-specifically-informed skepticism, particularly when they are feeling disoriented and uncomfortable.

So I need to take >5x more time preempting and clearing up people’s common misinterpretations and the unsound premises of their quick-snap-response questions than if my conversation partners just tried listening from a beginner’s mind.

@Rob, I think you are right about us needing be straight about why we think certain arguments are important. However, in my case that is not a bottleneck to sharing information. The bottlenecks are around people spending little time to listen to and consider mentioned arguments step-by-step, in a way where they leave open the possibility that they are not yet interpreting the terms and arguments as meant.

An example, to be frank, was your recent response to my new proposal for a foreseeable alignment difficulty. I think you assumed a philosophical definition of ‘intentionality’ there and then interpreted the conclusion of my claims to be that AI ‘lacks true intentionality’. That’s an inconsistent and maybe hasty reading of my comment, as the comment’s conclusion was that the intentionality in AI (ie. as having) will diverge from human intentionality.

I spent the last three weeks writing up a GDoc that I hope will not be misinterpreted in basic ways by you or other researchers (occasionally, interpretations are even literally incorrect – people literally say the opposite of part of a statement they heard or read from me a moment before).

It can be helpful if an interlocutor is straight-up about responding with their actual thoughts. I found out this way that some of my descriptive phrasing was way off – confusing and misdirecting the mental story people build up about the arguments.

But honestly, if the point is to have faster information transfers, can people not be a bit more careful about checking whether their interpretations are right? The difference for me is having had a chat with Rob three weeks ago and still taking another week right now asking for feedback from researchers I personally know to refine the writing even further.

Relatedly, a sense I got from reading posts and comments on LessWrong:

A common reason why a researcher ends up Strawmanning another researcher’s arguments or publicly claiming that another researcher is Strawmanning another researcher is that they never spend the time and attention (because they’re busy/overwhelmed?) to carefully read through the sentences written by the other researcher and consider how those sentences feel ambiguous in meaning and could be open to multiple interpretations.

When your interpretation of what (implicit) claim the author is arguing against seems particularly silly (even if the author plainly put a lot of effort into their writing), I personally think it’s often more productive (for yourself, other readers, and the author) to first paraphrase your interpretation back to the author.

That is, check in with the author in to clarify whether they meant y (your interpretation), before going on a long trail of explanations of why y does not match your interpretation of what the other AI x-safety researcher(s) meant when they wrote z.

I think your overall point—More Dakka, make AGI less weird—is right. In my experience, though, I disagree with your disagreement:

The short version is that while there is a lot written about alignment, I haven’t seen the core ideas organised into something clear enough to facilitate critically engaging with those ideas.

In my experience, there’s two main issues:

is low discoverability of “good” introductory resources.

is the existing (findable) resources are not very helpful if your goal is to get a clear understanding of the main argument in alignment—that the default outcome of building AGI without explictly making sure it’s aligned is strongly negative.

For 1, I don’t mean that “it’s hard to find any introductory resources.” I mean that it’s hard to know what is worth engaging with. Because of the problems in 2, its very time-consuming to try to get more than a surface-level understanding. This is an issue for me personally when the main purpose of this kind of exploration is to try and decide whether I want to invest more time and effort in the area.

For 2, there are many issues. The most common is that many resources are now quite old—are they still relevant? What is the state of the field now? Many are very long, or include “lists of ideas” without attempting to organise them into a cohesive whole, are single ideas, or are too vague or informal to evaluate. The result is a general feeling of “Well, okay...But there were a lot of assumptions and handwaves in all that, and I’m not sure if none of them matter.”

(If anyone is interested I can give feedback on specific articles in a reply—omitted here for length. I’ve read a majority of the links in the [1] footnote.)

Some things I think would help this situation:

Maintain an up-to-date list of quality “intro to alignment” resources.

Note that this shouldn’t be a catch-all for all intro resources. Being opinionated with what you include is a good thing as it helps newcomers judge relative importance.

Create a new introductory resource that doesn’t include irrelevant distractions from the main argument.

What I’m talking about here are things like timelines, scenarios and likelihoods, policy arguments, questionable analogies (especially evolutionary), appeals to meta-reasoning and the like, that don’t have any direct bearing on alignment itself and add distracting noncentral details that mainly serve to add potential points of disagreement.

I think Arbital does this best, but I think it suffers from being organised as a comprehensive list of ideas as separate pages rather than a cohesive argument supported by specific direct evidence. I’m also not sure how current it is.

People who are highly engaged in alignment write “What I think is most important to know about alignment” (which could be specific evidence or general arguments).

Lastly, when you say

Do you have some specific work in mind which provides this higher burden of proof?

I honestly would like more detailed investigation into why we can’t just fail to solve increasing context window for the next 100 years or something.

My impression is that people think it is possible to have a transformative AI without solving context window problem. Why do you think it is a must? Can’t AI still work without it?

I’m not sure it’ a must—hence “or something”—I just used it as a general example of some currently unsolved problem that may result in capability plateau. I do have an intuition that context window may help based on “it’s harder for me to think without using memory”.

If current trends hold, then large language models will be a pillar in creating AGI; which seems uncontroversial. I think one can then argue that after ignoring the circus around sentience means we should focus on the new current capabilities: reasoning, and intricate knowledge of how humans think and communicate. From that perspective there is a now a much stronger argument for manipulation. Outwitting humans prior to having human level intelligence is a major coup. PaLM’s ability to explain a joke and reason it’s way to understanding the collective human psyche is as impressive to me as Alphafold.

The goal posts have been moved on the Turing test and it’s important to point that out in any debate. Those in the liberal A.I. bias community have to at least acknowledge the particular danger of these LLM models that can reason positions. Naysayers need to have it thrown in their face that these lesser non-sentient, neural networks trained on a collection of words will eventually out debate them.

Every part of this sounds false to me. I don’t expect current trends to hold through a transition to AGI; I’d guess LLMs will not be a pillar in creating AGI; and I am very confident that these two claims are not uncontroversial, either among alignment researchers, within the existential risk ecosystem, or in ML.

Do you still hold this belief?

Language is one defining aspect of intelligence in general and human intelligence in particular. That an AGI wouldn’t utilize the capability of LLM’s doesn’t seem credible. The cross modal use cases for visual perception improvements (self-supervised labeling, pixel level segmentation, scene interpretation, casual inference) can be seen in recent ICLR/CVPR papers. The creation of github.com/google/BIG-bench should lend some credence that many leading institutions see a path forward with LLM’s.

As a proud member of the “discussion is net-negative” side, I shall gladly attempt to establish consensus using my favorite method — dictatorial power!

It seems like one of the most useful features of having agreement separate from karma is that it lets you vote up the joke and vote down the meaning :)

Would be curious to hear more about what kinds of discussion you think are net negative—clearly some types of discussion between some people are positive.

(Oh no, I was just making a joke, that people broadly against discussion might not be up for the sorts of consensus-building methods that acylhalide proposes—i.e. more discussion.)

(I guess their comment seems more obviously self-defeating and thus amusing when it appears in Recent Discussion, divorced of the context of the post.)

This joke also didn’t land with me.

K, I’ll try another one again in a year.

I got the joke after a moment. In retrospect, I’ll admit that it was a bit funny, but my initial offense at the literal meaning crushed any humor I might have felt in the moment.

What are examples of reasons people believe discussion is net-negative?

I would say that “AI risk advocacy among larger public” is probably net bad, and I’m very confused that this isn’t a much more popular option! I don’t see what useful thing the larger public is supposed to do with this information. What are we “advocating”?

Since I nonetheless think that AI risk outreach within ML is very net-positive, this poll strikes me as extraordinarily weak evidence that a lot of EAs think we shouldn’t do AI risk outreach within ML. Only 5 of the 55 respondents endorsed this for the general public, which strikes me as a way lower bar than ‘keep this secret from ML’.

You don’t need to be advocating a specific course of action. There are smart people who could be doing things to reduce AI x-risk and aren’t (yet) because they haven’t heard (enough) about the problem.

One reason you might be in favor of telling the larger public about AI risk absent a clear path to victory is that it’s the truth, and even regular people that don’t have anything to immediately contribute to the problem deserve to know if they’re gonna die in 10-25 years.

Time spent doing outreach to the general public is time not spent on other tasks. If there’s something else you could do to reduce the risk of everyone dying, I think most people would reflectively endorse you prioritizing that instead, if ‘spend your time warning us’ is either neutral or actively harmful to people’s survival odds.

I do think this is a compelling reason not to lie to people, if you need more reasons. But “don’t lie” is different from “go out of your way to choose a priority list that will increase people’s odds of dying, in order to warn them that they’re likely to die”.

You went from saying telling the general public about the problem is net negative to saying that it’s got an opportunity cost, and there are probably unspecified better things to do with your time. I don’t disagree with the latter.

If it were (sufficiently) net positive rather than net negative, then it would be worth the opportunity cost.