[Posting verbatim my blog post from a year ago since it might be relevant to this audience, and I hope it could generate a good discussion. As far as I can tell, cross-posting old material is OK here, though do let me know if not, and I will delete it. I do not intend to cross-post any more old posts from my blog. Note that this post was written for non-LW audience that is not necessarily familiar with longtermism. The advice at the end is aimed mostly at technical folks rather than policy makers. A final note is that this was written before some scandals related to longtermism/EA, though these should not have an impact on the content . --Boaz]

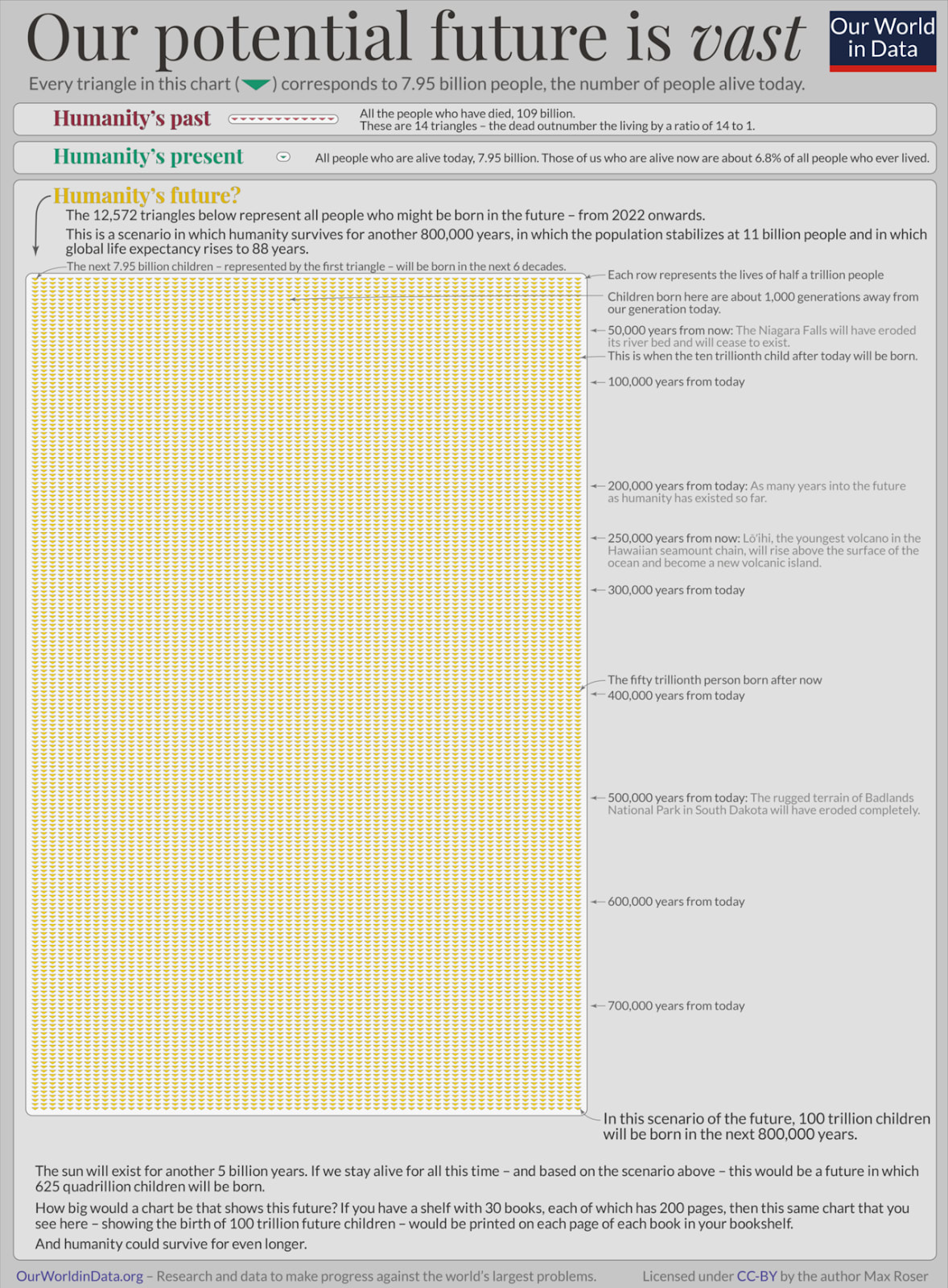

“Longtermism” is a moral philosophy that places much more weight on the well-being of all future generations than on the current one. It holds that “positively influencing the long-term future is a key moral priority of our time,” where “long term” can be really long term, e.g., “many thousands of years in the future, or much further still.” At its core is the belief that each one of the potential quadrillion or more people that may exist in the future is as important as any single person today.

Longtermism has recently attracted attention, some of it in alarming tones. The reasoning behind longtermism is natural: if we assume that human society will continue to exist for at least a few millennia, many more people will be born in the future than are alive today. However, since predictions are famously hard to make, especially about the future, longtermism invariably gets wrapped up with probabilities. Once you do these calculations, preventing an infinitely bad outcome, even if it would only happen with tiny probability, will have infinite utility. Hence longtermism tends to focus on so-called “existential risk”: The risk that humanity will go through in an extinction event, like the one suffered by the Neanderthals or Dinosaurs, or another type of irreversible humanity-wise calamity.

This post explains why I do not subscribe to this philosophy. Let me clarify that I am not saying that all longtermists are bad people. Many “longtermists” have given generously to improve people’s lives worldwide, particularly in developing countries. For example, none of the top charities of Givewell (an organization associated with the effective altruism movement, in which many prominent longtermists are members) focus on hypothetical future risks. Instead, they all deal with current pressing issues, including Malaria, childhood vaccinations, and extreme poverty. Overall the effective altruism movement has done much to benefit currently living people. Some of its members donated their kidneys to strangers: These are good people- morally better than me. It is hardly fair to fault people that are already contributing more than most others for caring about issues that I think are less significant.

Benjamin Todd’s estimates of Effective Altruism resource allocations

This post critiques the philosophy of longtermism rather than the particular actions or beliefs of “longtermists.” In particular, the following are often highly correlated with one another:

Belief in the philosophy of longtermism.

A belief that existential risk is not just a concern for the far-off future and a low-probability event, but there is a very significant chance of it happening in the near future (next few decades or at most a century).

A belief that the most significant existential risk could arise from artificial intelligence and that this is a real risk in the near future.

Here I focus on (1) and explain why I disagree with this philosophy. While I might disagree on specific calculations of (2) and (3), I fully agree with the need to think and act regarding near-term risks. Society tends to err on the side of being too myopic. We prepare too little even for risks that are not just predictable but are also predicted, including climate change, pandemics, nuclear conflict, and even software hacks. It is hard to motivate people to spend resources for safety when the outcome (bad event not happening) is invisible. It is also true that over the last decades, humanity’s technological capacities have grown so much that for the first time in history, we are capable of doing irreversible damage to our planet.

In addition to the above, I agree that we need to think carefully about the risks of any new technology, particularly one that, like artificial intelligence, can be very powerful but not fully understood. Some AI risks are relevant to the shorter term: they are likely over the next decade or are already happening. There are several books on these challenges. None of my critiques apply to such issues. At some point, I might write a separate blog post about artificial intelligence and its short and long-term risks.

My reasons for not personally being a “longtermist” are the following:

The probabilities are too small to reason about.

Physicists know that there is no point in writing a measurement up to 3 significant digits if your measurement device has only one-digit accuracy. Our ability to reason about events that are decades or more into the future is severely limited. At best, we could estimate probabilities up to an order of magnitude, and even that may be optimistic. Thus, claims such as Nick Bostrom’s, that “the expected value of reducing existential risk by a mere one billionth of one billionth of one percentage point is worth a hundred billion times as much as a billion human lives” make no sense to me. This is especially the case since these “probabilities” are Bayesian, i.e., correspond to degrees of belief. If, for example, you evaluate the existential-risk probability by aggregating the responses of 1000 experts, then what one of these experts had for breakfast is likely to have an impact larger than 0.001 percent (which, according to Bostrom, would correspond to much more than human lives). To the extent we can quantify existential risks in the far future, we can only say something like “extremely likely,” “possible,” or “can’t be ruled out.” Assigning numbers to such qualitative assessments is an exercise in futility.

I cannot justify sacrificing current living humans for abstract probabilities.

Related to the above, rather than focusing on specific, measurable risks (e.g., earthquakes, climate change), longtermism is often concerned with extremely hard to quantify risks. In truth, we cannot know what will happen 100 years into the future and what would be the impact of any particular technology. Even if our actions will have drastic consequences for future generations, the dependence of the impact on our choices is likely to be chaotic and unpredictable. To put things in perspective, many of the risks we are worried about today, including nuclear war, climate change, and AI safety, only emerged in the last century or decades. It is hard to underestimate our ability to predict even a decade into the future, let alone a century or more.

Given that there is so much suffering and need in the world right now, I cannot accept a philosophy that prioritizes abstract armchair calculations over actual living humans. (This concern is not entirely hypothetical: Greaves and MacAskill estimate that $100 spent on AI safety would, in expectation, correspond to saving a trillion lives and hence would be “far more than the near-future benefits of bednet distribution [for preventing Malaria],” and recommend that it is better that individuals “fund AI safety rather than developing world poverty reduction.”)

Moorhouse compares future humans to ones living far away from us. He says that just like “something happening far away from us in space isn’t less intrinsically bad just because it’s far away,” we should care about humans in the far-off future as much as we care about present ones. But I think that we should care less about very far away events, especially if it’s so far away that we cannot observe them. E.g., as far as we know, there may well be trillions of sentient beings in the universe right now whose welfare can somehow be impacted by our actions.

We cannot improve what we cannot measure.

An inherent disadvantage of probabilities is that they are invisible until they occur. We have no direct way to measure whether a probability of an event X has increased or decreased. So, we cannot tell whether our efforts are working or not. The scientific revolution involved moving from armchair philosophizing to making measurable predictions. I do not believe we can make meaningful progress without concrete goals. For some risks, we do have quantifiable goals (Carbon emissions, number of nuclear warheads). Still, there are significant challenges to finding a measurable proxy for very low-probability and far-off events. Hence, even if we accept that the risks are real and vital, I do not think we can directly do anything about them before finding such proxies.

Proxies do not have to be perfect: Theoretical computer science made much progress using the imperfect measure of worst-case asymptotic complexity. The same holds for machine learning and artificial benchmarks. It is enough that proxies encourage the generation of new ideas or technologies and achieve gradual improvement. One lesson from modern machine learning is that the objective (aka loss function) doesn’t have to perfectly match the task for it to be useful.

Long-term risk mitigation can only succeed through short-term progress.

Related to the above, I believe that addressing long-term risks can only be successful if it’s tied to shorter-term advances that have clear utility. For example, consider the following two extinction scenarios:

1. The actual Neanderthal extinction.

2. A potential human extinction 50 years from now due to total nuclear war.

I argue that the only realistic scenario to avoid extinction in both cases is a sequence of actions that improve some measurable outcome. While sometimes extinction could theoretically be avoided by a society making a huge sacrifice to eliminate a hypothetical scenario, this could never actually happen.

While the reasons for the Neanderthal extinction are not fully known, most researchers believe that Neanderthals were out-competed by our ancestors—modern humans—who had better tools and ways to organize society. The crucial point is that the approaches to prevent extinction for Neanderthal were the same ones to improve their lives in their current environment. They may not have been capable of doing so, but it wasn’t because they were working on the wrong problems.

Contrast this with the scenario of human extinction through total nuclear war. In such a case, our conventional approaches for keeping nuclear arms in check, such as international treaties and sanctions, have failed. Perhaps in hindsight, humanity’s optimum course of action would have been a permanent extension of the middle ages, stopping the scientific revolution from happening through restricting education, religious oppression, and vigorous burning-at-stake of scientists. Or perhaps humanity could even now make a collective decision to go back and delete all traces of post 17th-century science and technology.

I cannot rule out the possibility that, in hindsight, one of those outcomes would have had more aggregate utility than our current trajectory. But even if this is the case, such an outcome is simply not possible. Humanity can not and will not halt its progress, and solutions to significant long-term problems have to arise as a sequence of solutions to shorter-range measurable ones, each of which shows positive progress. Our only hope to avoid a total nuclear war is through piecemeal quantifiable progress. We need to use diplomacy, international cooperation, and monitoring technologies to reduce the world’s nuclear arsenal one warhead at a time. This piecemeal, incremental approach may or may not work, but it’s the only one we have.

Summary: think of the long term, but act and measure in the short term.

It is appropriate for philosophers to speculate on hypothetical scenarios centuries into the future and wonder whether actions we take today could influence them. However, I do not believe such an approach will, in practice, lead to a positive impact on humanity and, if taken to the extreme, may even have negative repercussions. We should maintain epistemic humility. Statements about probabilities involving fractions of percentage points, or human lives in the trillions, should raise alarm bells. Such calculations can be particularly problematic since they can lead to a “the end justifies the means” attitude, which can accept any harm to currently living people in the name of the practically infinite multitudes of future hypothetical beings.

We need to maintain the invariant that, even if motivated by the far-off future, our actions “first do no harm” to living, breathing humans. Indeed, as I mentioned, even longtermists don’t wake up every morning thinking about how to reduce the chance that something terrible happens in the year 1,000,000 AD by 0.001%. Instead, many longtermists care about particular risks because they believe these risks are likely in the near-term future. If you manage to make a convincing case that humanity faces a real chance of near-term total destruction, then most people would agree that this is very very bad, and we should act to prevent it. It doesn’t matter whether humanity’s extinction is two times or a zillion times worse than the death of half the world’s population. Talking about trillions of hypothetical beings thousands of years into the future only turns people off. There is a reason that Pascal’s Wager is not such a winning argument, and I have yet to meet someone who converted to a particular religion because it had the grisliest version of hell.

This does not mean that thinking and preparing for longer-term risks is pointless. Maintaining seed banks, monitoring asteroids, researching pathogens, designing vaccine platforms, and working toward nuclear disarmament, are all essential activities that society should take. Whenever a new technology emerges, artificial intelligence included, it is crucial to consider how it can be misused or lead to unintended consequences. By no means do I argue that humanity should spend all of its resources only on actions that have a direct economic benefit. Indeed, the whole enterprise of basic science is built on pursuing directions that, in the short term, increase our knowledge but do not have practical utility. Progress is not measured only in dollars, but it should be measured somehow. Epistemic humility also means that we should be content with working on direct, measurable proxies, even if they are not perfect matches for the risk at hand. For example, the probability of extinction via total nuclear war might not be a direct function of the number of deployed nuclear warheads. However, the latter is still a pretty good proxy for it.

Similarly, even if you are genuinely worried about long-term risk, I suggest you spend most of your time in the present. Try to think of short-term problems whose solutions can be verified, which might advance the long-term goal. A “problem” does not have to be practical: it can be a mathematical question, a computational challenge, or an empirically verifiable prediction. The advantage is that even if the long-term risk stays hypothetical or the short-term problem turns out to be irrelevant to it, you have still made measurable progress. As has happened before, to make actual progress on solving existential risk, the topic needs to move from philosophy books and blog discussions into empirical experiments and concrete measures.

Acknowledgments: Thanks to Scott Aaronson and Ben Edelman for commenting on an earlier version of this post.

My dissatisfaction with longtermism as a philosophical position comes from the fact that its conclusion is much more obvious than its premises. I think it’s one of the worst sins of philosophy. When the conclusion is less intuitive than the premises, it borrows credibility from them and feels enlightening. When the situation is inversed, not only we are dissapointed with the lack of new insights, but we are also left confused and feeling as if the conclusion loses its credibility.

In his book, MacAskill construct a convoluted and complicated argument invoking total utilitarianism, self fulfilling prophesy, pascallian reasoning and assigning future people present ethical value. He makes all these controversial assumptions in order to prove a pretty conventional idea that it’s better if humanity achieves its full potential instead of going extinct.

Basically, he creates a new rallying flag and a group identity where none is needed.

Previously I could say: “I prefer humans not to go extinct”, and my conversation partner would just reply with: “Obviously, duh”. Or maybe, if they wanted to appear edgy, they would start devil advocating in favour of human extinction. But at every point we would be understanding that pro-human-extinction position is completely fringe while pro-human-survival is a mainstream and common sense position.

Nowdays, instead, if I say that I’m a longtermist, whoever hears it, gets all sort of unnecessary assumptions about my position. And there are all kind of completely straight-face responses, arguing that longtermism is incorrect due to some alleged or real mistake in MacAskill’s reasoning. As if the validity of humanity’s longterm survival depends on it. Now it feels as a fringe position, a very specific point in the idea-space, instead of common sense. And I think such change is very unhelpful for our cause.

Indeed many “longtermists” spend most of their time worrying about risks that they believe (rightly or not) have a large chance of materializing in the next couple of decades.

Talking about tiny probabilities and trillions of people is not needed to justify this, and for many people it’s just a turn off and a red flag that something may be off with your moral intuition. If someone tries to sell me a used car and claims that it’s a good deal and will save me $1K then I listen to them. If someone claims that it would give me an infinite utility then I stop listening.

True enough. There was someone the other day on Twitter who out of sheer spite for longtermists (specifically, a few ones who have admittedly rather bonkers and questionable political ideas) ended up posting a philosophy piece that was basically “you know, maybe extinction is actually okay” and that made me want to hit my head against a wall. Never mind that this was someone who would get rightfully angry about people dying from some famine or from the damages of climate change. What, does it make it better if at least everyone else dies too, so it’s fair?

Glad you posted this.

I think everyone agrees we should take into account future people to some degree, we just disagree on how far out and to what degree.

I choose to believe that the whole ”.0001% chance of saving all future lives is still more valuable than saving current lives” is a starting point to convince people to care, but isn’t intended to be the complete final message. Like telling kids atoms have electrons going in circles, its a lie but a useful start.

Maybe I’m wrong and people actually believe that though. I believe that argument is usually a starting point that SHOULD get more nuanced such as, but we arent certain about the future and we need to discount for our uncertainty.

I interpreted this post as anti-longtermism but I think most real longtermists would agree with most of your points here except for one. I think your argument could be pro-longtermism if you accepted the ”.0001% chance of saving all future lives is still more valuable than saving current lives” as a good starting point rather than arguing against it.

All to say I agree with almost all your points but I still call myself a long termist.

I’ll actually offer a perspective from the viewpoint of someone who thinks this is false, and you can build a perfectly sensible moral framework in which future people, themselves, are not moral subjects.

First, why I think we don’t need this: the view that a future human life is worth as much as a present human one clearly doesn’t gel with any sensible moral intuition. Future human lives are potential. As such they only exist in a state of superposition about both how many there are and who they are. The path to certain specific individuals existing is entirely chaotic (in fact, the very process of biological conception is chaotic, and happens at such a microscopic scale that I wouldn’t be surprised if true quantum effects played a non-trivial effect in the outcomes of some of the steps, e.g. Van der Waals forces making one specific sperm stick to the egg etc). In normal circumstances, you wouldn’t consider “kill X to make Y pop into existence” ethical (for example, if you were given the chance to overwrite someone’s mind and place a different mind in their body). Yet countless choices always swap potential future individuals for other potential future individuals, as the chances of the future get reshuffled. Clearly “future people” are not any specific individual moral subjects: they are an idea, a phenomenon we can only construe in vague terms. And the further from the present we go, the vaguer those terms.

Second, the obvious fact that most approaches which value future people as much as present ones, or at least don’t discount them enough, lead to patently absurd conclusion such as that abortion is murder, but also using contraception is murder, but also not reproducing maximally from as soon as you hit fertile age is murder. Obviously nonsense. If you only discount future people a little this doesn’t fix the issue because you can always stack enough of them on the plate to justify completely overriding present people’s preferences.

How much discount is discounting “enough”? Well, I’d say any discounting rates fast enough to make sure that it’s essentially biologically impossible for humans to grow in number faster than that will do the trick; then no matter how much reproduction you project, you will never get to the point of those absurdities popping in. But that’s actually some really high discounting rates! I can imagine human population doubling reasonably every 25 years if everyone put their minds to it (give every couple time to grow to maturity and then pop out 4 children asap), so you need some discount rate that’s like 50% over 20 years or so. That’s a lot! It basically leads to humans past one century or so no mattering at all. That actually doesn’t even square with our other moral intuition that we should, for example, care about not destroying the Earth so our descendants have a place to live.

But nor are those rates enough to fix the problems either! Because along comes a longtermist and they tell you that hey, who knows, maybe in 42,356 AD there’ll be giant Dyson spheres running planet-sized GPU clusters expanding via Von Neumann probes which can instantiate human EMs with a doubling time of one day, and what the hell can you say to that? You can’t discount future humans over 50% per day, and if you don’t, the longtermists’ imagined EMs will eventually overcome all other concerns by sheer power of exponential growth. You can’t fight with exponentials, if they’re not going down, they’re going up!

Hence what I think is the only consistent solution: future humans, in themselves, are worth zero. Nada. Nothing. Zilch. What is worth something is the values and desires of present humans, and those values include concerns about the future. For example, consider a young just married couple. They plan to have children, and thus they desire to see a world that they consider happy and safe for those children to eventually grow up on. The children themselves aren’t subjects; they have no wants or needs; the parents merely assume that being human, they will crave certain shared properties of the world, and their desire is to have children whose wants are reasonably satisfied. Note that they could be wrong about this, children turn out to want different things from what their parents expected all the time! But as a general rule, the couple’s own desires are all that matters here. Conversely, when a child is actually born, their wants start mattering too; and if they ever conflict with their parents’ expectation of them, we’d say the child’s take precedence, because now they’re an actual human being.

Similarly, a grandpa on his death bed could be more or less at peace depending on whether he thinks his descendants will live in a happy world, or struggle against a failing one. And these spheres of concern can extend even further, up to people like our longtermists who care about the extreme reaches of the future of humanity. But then again, here the actual moral good that needs to be weighed isn’t the amount of imagined future humans, which can be made arbitrarily large in a pointless game of ethical Calvinball: it’s the (much more limited) desires and feelings of the longtermist. Which can be easily weighed against other similar moral weights.

So essentially there you have it. If you want to avoid global warming or AI extinction because you want there to be humans 200 years from now, I don’t think you’re protecting those future humans, but rather, you’re protecting your own ability to believe that there will exist humans 200 years in the future. This is not trivial because many, in fact most, humans wish for there to still be a world in the future, at least for their direct descendants, whom they are connected to. This inevitably leads to long term preservation anyway as long as every generation wishes the same for the next ones—just one step at a time. Every group gets naturally to worry about the immediate future that they are best positioned to predict and understand, and steer it as they see it fit.

I really like this!

The hypothetical future people calculation is an argument why people should care about the future, but as you say the vast majority of currently living humans (a) already care about the future and (b) are not utilitarians and so this argument anyway doesn’t appeal to them.

Wow, thank you this is a really well made point. I see now how accounting for future lives seems like double counting their desires with our own desires to have their desires fulfilled.

You already put a lot of effort into a response so don’t feel obliged to respond but some things in my mind that I need to work out about this:

Can’t this argument do a bit too much “I’m not factoring in the utility of X (future peoples happiness) but I am instead factoring in my desires to make X a reality” in a way that you could apply it to any utility function parameter. For instance, “my utility calculation doesn’t factor in actually (preventing malaria), but I am instead factoring in my desires to (prevent malaria).” Maybe while the sentiment is true, it seems like it can apply to everything.

Another unrelated thought I am working with. If the goal is to have grandpa on his deathbed happy thinking that the future will be okay, wouldn’t this goal be satisfied by lying to grandpa? In other words if we have an all powerful aligned AGI and tell it give it the utility function you outlined, where we maximize our desires to have the future happy. Wouldn’t it just find a way to make us think the future would be okay by doing things we think would work? As opposed to actually assigning utility to future people actually being happy, which the AGI would then actually improve the future.

You helped me see the issues with assigning any utility to future people. You changed my opinion that that isn’t great. I guess I am struggling to accept your alternative as I think it may have a lot of the same issues if not a few more.

I think this operates on two different level.

The level I am discussing is: “I consider all sentient beings currently alive as moral subject; I consider any potential but not-yet-existing sentient beings not subjects, but objects of the existing beings’ values”.

The one you’re proposing is one far removed, sort of the “solipsist” level: “I consider only myself as the sole existing moral subject, as I can only be sure of my own inner experiences; however I feel empathy and compassions for these possibly-P-zombie creatures that move around me, thus I do good because I enjoy the warm fuzzies that follow”.

Ultimately I do think in some sense all our morality is rooted in that sort of personal moral intuition. If no one felt any kind of empathy or concern for others we probably wouldn’t have morality at all! But yeah, I do decide out of sheer symmetry that it’s not likely that somehow I am the only special human being who experiences the world, and thus I should treat all others as I would myself.

Meanwhile with future humans the asymmetry is real. Time translation doesn’t work the same way as space translation does. Also, even if I wanted to follow a logical extension step of “well, most humans care about the future, therefore I may as well take a shortcut and consider future humans themselves as moral subjects, to account in a more direct way for the same effect”, then I should do so by weighing approximately how actual living humans care about the future, which in overwhelming majority means “our kids and grandkids”, and not the longtermists’ future hypothetical em clusters.

Well, I suppose yes, you could in theory end up with an AGI whose goal is simply letting us all die believing that everyone will be happy after us. The fiction would be horribly complex; we’d need to be all sterilised but actually deliver babies that are the AGI’s construct (lest more humans come into the equation who need to be deceived!). Then when the last true human dies, the AGI goes “haha, got you suckers” and starts disassembling everything; or turns itself off, having completed its purpose. Not sure how to dodge that (or even whether I can say it’s strictly speaking bad, though I guess it is insofar as people don’t like being lied to), but I think it’d be a lot simpler for the AGI to just actually make the future good.

There is a meta question here whether morality is based on personal intuition or calculations. My own inclination is that utility calculations would only make a difference “in the margin” but the high level decision are made by our moral intuition.

That is, we can do calculations to decide if we fund Charity A or Charity B in similar areas, but I doubt that for most people major moral decisions actually (or should) boil down to calculating utility functions.

But of course to each their own, and if someone finds math useful to make such decisions then whom am I to tell them not to do it.

Yeah, I think calculations can be a tool but ultimately when deciding a framework we’re trying to synthesise our intuitions into a simple set of axioms from which everything proceeds. But the intuitions remain the origin of it all. You could design some game theoretical framework for what guarantees a society to run best without appealing to any moral intuition, but that would probably look quite alien and cold. Morality is one of our terminal values, we just try to make sense of it.

Thanks! I should say that (as I wrote on windows on theory) one response I got to that blog was that “anyone who writes a piece called “Why I am not a longtermist” is probably more of a longtermist than 90% of the population” :)

That said, if the 0.001% is a lie then I would say that it’s an unproductive one, and one that for many people would be an ending point rather than a starting one.

Thank you for a very thorough post. I think your writing has served me as a more organized account of some of my own impressions opposing longtermisim.

I agree with CrimsonChin in that I think there’s a lot of your post many longtermists would agree with, including the practicality of focusing on short-term sub-goals. Also, I personally believe that initiatives like global health, poverty reduction, etc. probably improve the prospects of the far future, even if their expected value seems less than X-risk mitigation.

Nonetheless, I still think we should be motivated by the immensity of the future even if it is off set by tiny probabilities and there are huge margins of error, because the lower bounds of these estimates appear to me as sufficiently high to be very compelling. The post How Many Lives Does X-Risk Work Save From Nonexistance On Average demonstrates my thinking on this by having estimates of future lives that vary by dozens of orders of magnitude(!) but still arrives at very high expected values for X-Risk work even on the lower bounds.

Even I don’t really feel anything when I read such massive numbers, and I acknowledge how large the intervals of these estimates are, but I wouldn’t say they “make no sense to me” or that ‘To the extent we can quantify existential risks in the far future, we can only say something like “extremely likely,’ ‘possible,’ or ‘can’t be ruled out.’”

For what it’s worth, I use to essentially be an egoist, and was unmoved by all of the charities I had ever encountered. It seemed to me that humanity was on a good trajectory and my personal impact would be negligible. It was only after I started thinking about really large numbers, like the duration of the universe, the age of humanity, the number of potential minds in the universe (credit to SFIA), how neglected these figures were, and moral uncertainty, that I started to feel like I could and should act for others.

There are definitely many, possibly most, contexts where incredibly large or small numbers can be safely disregarded. I wouldn’t be moved by them in adversarial situations, like Pascal’s Mugging, or when doing my day-to-day moral decision making. But for question’s like “What should I really care deeply about?” I think they should be considered.

As for Pascal’s Wager, It calls for picking a very specific God to worship out of a space of infinite possible contradictory gods, and this infinitely small probability of success cancels out the infinite reward of heaven over hell or non-existance. Dissimilarly, Longtermism isn’t committed to any specific action regarding the far future, just the well being of entities in the future generally. I expect that most longtermists would gladly pivot away from a specific cause area (like AI alignment) if they were shown some other cause (E.g. a planet-killing asteroid certainly colliding with Earth in 100 years) was more likely to similarly adversely impact the far future.

I think the whole concept of “saving from non-existence” makes very little sense. Are human souls just floating into a limbo, waiting to be plucked out by the lifeline of a body to inhabit? What are we saving them from? Who are we saving? How bad can a life be before the saving actually counts as damning?

There’s no real answers, especially if you don’t want to get metaphysical. IMO the only forms of utilitarianism that make sense are based on averages, not total sums. The overall size of the denominator matters little in and of itself.

Strong agree. The framework of saving from non existence leads to more problems and confusions than helps.

It’s not the immensity of the future that motivates me to care. If the future consists of immortal people living really awesome and fullfilling lives—its a great future. If doesn’t really matter to me if there are billions or nonilions of them. I would definetely not sacrifice the immortality of people to have more of them in total being instantiated in the universe. The key point is how awesome and fullfilling the lives are, not their number.

Sorry for the late reply, I haven’t commented much on LW and it didn’t appreciate the time it would take for someone to reply to me, so I missed this until now. If I reply to you, Ape in the coat, does that notify dr_s too?

If I understand dr_s’s quotation, I believe he’s responding to the post I referenced. How Many Lives Does X-Risk Work Save from Non-Existence includes pretty early on:

It seems pretty obvious to me that in almost any plausible scenario, the lifespan of a distant future entity with moral weight will be very different from what we currently think of as a natural life span (rounded to 100 years in the post I linked), but making estimates in terms of “lives saved from non existence” where life = 100 years is useful for making comparisons to other causes like “lives saved per $1,000 via malaria bed nets.” It also seems appropriate for the post not to assume a discount rate and to leave that to the reader to apply themselves on top of the estimates presented.

I prefer something like “observer moments that might not have occurred” to “lives saved.” I don’t have strong preferences between a relatively small number of entities having long lives or more numerous entities having shorter lives, so long as the quality of the life per moment is held constant.

As for dr_S’s “How bad can a life be before the savings actually counts as damning” this seems easily resolvable to me by just allowing “people” of the far future the right to commit suicide, perhaps after a short waiting period. This would put a floor on the suffering they experience if they can’t otherwise be guaranteed to have great lives.

I don’t presume to tell people what they should care about, and if you feel that thinking of such numbers and probabilities gives you a way to guide your decisions then that’s great.

I would say that, given how much humanity changed in the past and increasing rate of change, probably almost none of us could realistically predict the impact of our actions more than a couple of decades to the future. (Doesn’t mean we don’t try- the institution I work for is more than 350 years old and does try to manage its endowment with a view towards the indefinite future…)

If Neanderthals could have created a well aligned agent,far more powerful than themselves, they would still be around and we, almost certainly, would not.

The mereset possibility of creating super human, self improving, AGI is a total philosophical game changer.

My personal interest is in the interaction between longtermism and the Fermi paradox—Any such AGIs actions are likely to be dominated by the need to prevail over any alien AGI that it ever encounters as such an encounter is almost certain to end one or the other.

Just want to say there seems to be a community wide misconception between existential, suffering, and extinction risks. An existential risk just broadly means the disempowerment of humanity and suffering/extinction are a subset of that. It’s plausible there’s a future without extinction or (more) suffering that does involve disempowerment.

Thanks. I tried to get at that with the phrase “irreversible humanity-wide calamity”.