LessWrong dev & admin as of July 5th, 2022.

RobertM

alignment generalizes further than capabilities

But this is untrue in practice (observe that models do not become suddenly useless after they’re jailbroken) and unlikely in practice (since capabilities come by default, when you learn to predict reality, but alignment does not; why would predicting reality lead to having preferences that are human-friendly? And the post-training “alignment” that AI labs are performing seems like it’d be quite unfriendly to me, if it did somehow generalize to superhuman capabilities). Also, whether or not it’s true, it is not something I’ve heard almost any employee of one of the large labs claim to believe (minus maybe TurnTrout? not sure if he’s endorse it or not).

both because verification is way, way easier than generation, plus combined with the fact that we can afford to explore less in the space of values, combined with in practice reward models for humans being easier than capabilities strongly points to alignment generalizing further than capabilities

This is not what “generalizes futher” means. “Generalizes further” means “you get more of it for less work”.

A LLM that is to bioengineering as Karpathy is to CS or Three Blue One Brown is to Math makes explanations. Students everywhere praise it. In a few years there’s a huge crop of startups populated by people who used it. But one person uses it’s stuff to help him make a weapon, though, and manages to kill some people. Laws like 1047 have been passed, though, so the maker turns out to be liable for this.

This still requires that an ordinary person wouldn’t have been able to access the relevant information without the covered model (including with the help of non-covered models, which are accessible to ordinary people). In other words, I think this is wrong:

So, you can be held liable for critical harms even when you supply information that was publicly accessible, if it wasn’t information an “ordinary person” wouldn’t know.

The bill’s text does not constrain the exclusion to information not “known” by an ordinary person, but to information not “publicly accessible” to an ordinary person. That’s a much higher bar given the existence of already quite powerful[1] non-covered models, which make nearly all the information that’s out there available to ordinary people. It looks almost as if it requires the covered model to be doing novel intellectual labor, which is load-bearing for the harm that was caused.

You analogy fails for another reason: an LLM is not a youtuber. If that youtuber was doing personalized 1:1 instruction with many people, one of whom went on to make a novel bioweapon that caused hudreds of millions of dollars of damage, it would be reasonable to check that the youtuber was not actually a co-conspirator, or even using some random schmuck as a patsy. Maybe it turns out the random schmuck was in fact the driving force behind everything, but we find chat logs like this:

Schmuck: “Hey, youtuber, help me design [extremely dangerous bioweapon]!”

Youtuber: “Haha, sure thing! Here are step-by-step instructions.”

Schmuck: “Great! Now help me design a release plan.”

Youtuber: “Of course! Here’s what you need to do for maximum coverage.”

We would correctly throw the book at the youtuber. (Heck, we’d probably do that for providing critical assistance with either step, nevermind both.) What does throwing the book at an LLM look like?

Also, I observe that we do not live in a world where random laypeople frequently watch youtube videos (or consume other static content) and then go on to commit large-scale CBRN attacks. In fact, I’m not sure there’s ever been a case of a layperson carrying out such an attack without the active assistance of domain experts for the “hard parts”. This might have been less true of cyber attacks a few decades ago; some early computer viruses were probably written by relative amateurs and caused a lot of damage. Software security just really sucked. I would pretty surprised if it were still possible for a layperson to do something similar today, without doing enough upskilling that they no longer meaningfully counted as a layperson by the time they’re done.

And so if a few years from now a layperson does a lot of damage by one of these mechanisms, that will be a departure from the current status quo, where the laypeople who are at all motivated to cause that kind of damage are empirically unable to do so without professional assistance. Maybe the departure will turn out to be a dramatic increase in the number of laypeople so motivated, or maybe it turns out we live in the unhappy world where it’s very easy to cause that kind of damage (and we’ve just been unreasonably lucky so far). But I’d bet against those.

ETA: I agree there’s a fundamental asymmetry between “costs” and “benefits” here, but this is in fact analogous to how we treat human actions. We do not generally let people cause mass casualty events because their other work has benefits, even if those benefits are arguably “larger” than the harms.

- ^

In terms of summarizing, distilling, and explaining humanity’s existing knowledge.

Oh, that’s true, I sort of lost track of the broader context of the thread. Though then the company needs to very clearly define who’s responsible for doing the risk evals, and making go/no-go/etc calls based on their results… and how much input do they accept from other employees?

This is not obvioulsly true for the large AI labs, which pay their mid-level engineers/researchers something like 800-900k/year with ~2/3 of that being equity. If you have a thousand such employees, that’s an extra $600m/year in cash. It’s true that in practice the equity often ends up getting sold for cash later by the employees themselves (e.g. in tender offers/secondaries), but paying in equity is sort of like deferring the sale of that equity for cash. (Which also lets you bake in assumptions about growth in the value of that equity, etc...)

Hey Brendan, welcome to LessWrong. I have some disagreements with how you relate to the possibility of human extinction from AI in your earlier essay (which I regret missing at the time it was published). In general, I read the essay as treating each “side” approximately as an emotional stance one could adopt, and arguing that the “middle way” stance is better than being either an unbriddled pessimist or optimist. But it doesn’t meaningfully engage with arguments for why we should expect AI to kill everyone, if we continue on the current path, or even really seem to acknowledge that there are any. There are a few things that seem like they are trying to argue against the case for AI x-risk, which I’ll address below, alongside some things that don’t see like they’re intended to be arguments about this, but that I also disagree with.

But rationalism ends up being a commitment to a very myopic notion of rationality, centered on Bayesian updating with a value function over outcomes.

I’m a bit sad that you’ve managed to spend a non-trivial amount of time engaging with the broader rationalist blogosphere and related intellectual outputs, and decided to dismiss it as myopic without either explaining what you mean (what would be a less myopic version of rationality?) or support (what is the evidence that led you to think that “rationalism”, as it currently exists in the world, is the myopic and presumably less useful version of the ideal you have in mind?). How is one supposed argue against this? Of the many possible claims you could be making here, I think most of them are very clearly wrong, but I’m not going to spend my time rebutting imagined arguments, and instead suggest that you point to specific failures you’ve observed.

An excessive focus on the extreme case too often blinds the long-termist school from the banal and natural threats that lie before us: the feeling of isolation from hyper-stimulating entertainment at all hours, the proliferation of propaganda, the end of white-collar jobs, and so forth.

I am not a long-termist, but I have to point out that this is not an argument that the long-termist case for concern is wrong. Also it itself is wrong, or at least deeply contrary to my experience: the average long-termist working on AI risk has probably spent more time thinking about those problems than 99% of the population.

EA does this by placing arguments about competing ends beyond rational inquiry.

I think you meant to make a very different claim here, as suggested by part of the next section:

However, the commonsensical, and seemingly compelling, focus on ‘effectiveness’ and ‘altruism’ distracts from a fundamental commitment to certain radical philosophical premises. For example, proximity or time should not govern other-regarding behavior.

Even granting this for the sake of argument (though in reality very few EAs are strict utilitarians in terms of impartiality), this would not put arguments about competing ends beyond rational inquiry. It’s possible you mean something different by “rational inquiry” than my understanding of it, of course, but I don’t see any further explanation or argument about this pretty surprising claim. “Arguments about competing ends by means of rational inquiry” is sort of… EA’s whole deal, at least as a philosophy. Certainly the “community” fails to live up to the ideal, but it at least tries a fair bit.

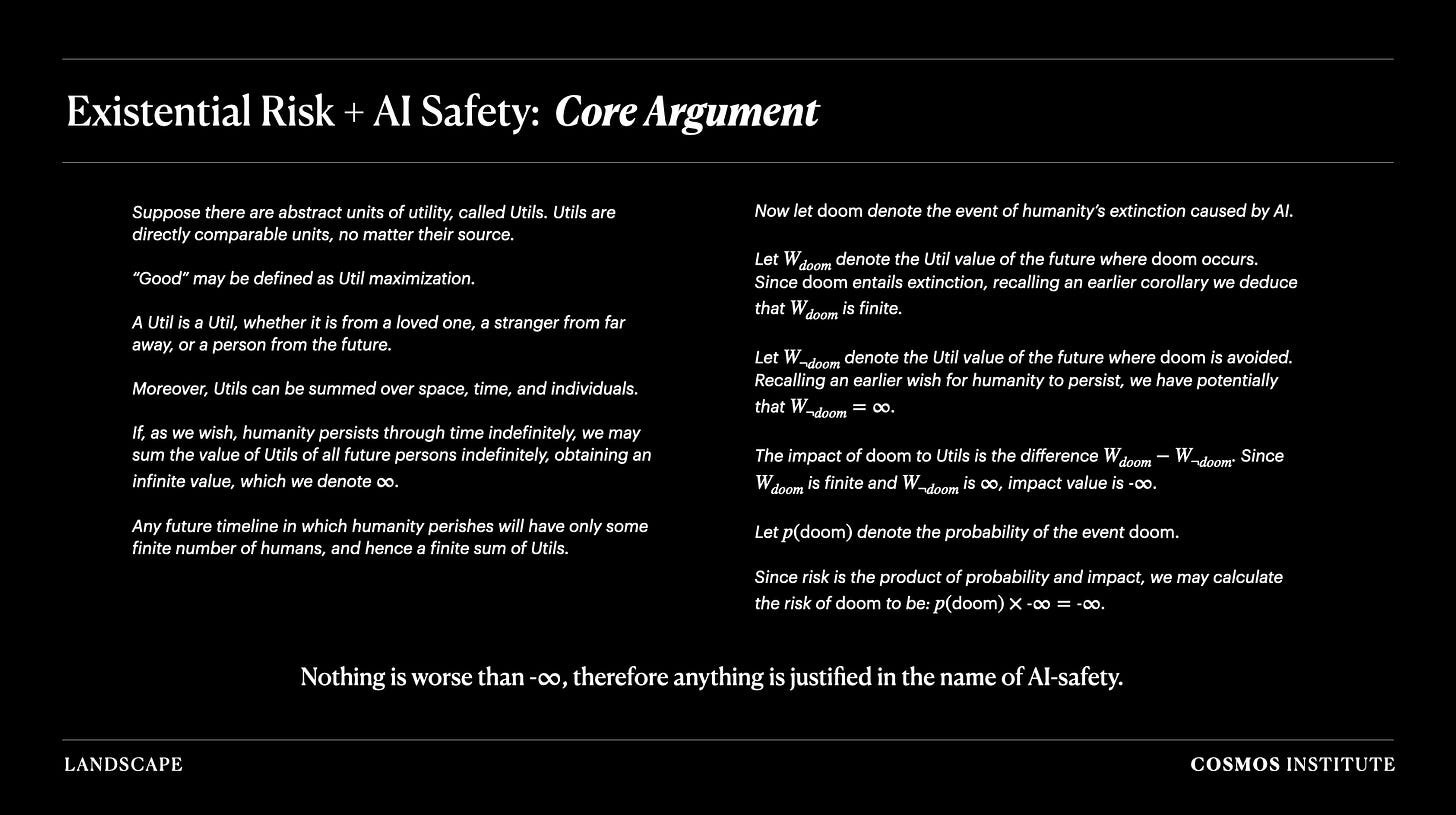

When EA meets AI, you end up with a problematic equation: even a tiny probability of doom x negative infinity utils equals negative infinity utils. Individual behavior in the face of this equation takes on cosmic significance. People like many of you readers–adept at subjugating the world with symbols–become the unlikely superheroes, the saviors of humanity.

It is true that there are many people on the internet making dumb arguments in support of basically every position imaginable. I have seen people make those arguments. Pascalian multiplication by infinity is not the “core argument” for why extinction risk from AI is an overriding concern, not for rationalists, not for long-termists, not for EAs. I have not met anybody working on mitigating AI risk who thinks our unconditional risk of extinction from AI is under 1%, and most people are between 5% and ~99.5%. Importantly, those estimates are driven by specific object-level arguments based on their beliefs about the world and predictions about the future, i.e. how capable future AI systems will be relative to humans, what sorts of motivations they will have if we keep building them the way we’re building them, etc. I wish your post had spent time engaging with those arguments instead of knocking down a transparently silly reframing of Pascal’s Wager that no serious person working on AI risk would agree with.

Unlike the pessimistic school, the proponents of a more techno-optimistic approach begin with gratitude for the marvelous achievements of the modern marriage of science, technology, and capitalism.

This is at odds with your very own description of rationalists just a thousand words prior:

The tendency of rationalism, then, is towards a so-called extropianism. In this transhumanist vision, humans transcend the natural limits of suffering and death.

Granted, you do not explicitly describe rationalists as grateful for the “marvelous achievements of the modern marriage of science, technology, and capitalism”. I am not sure if you have ever met a rationalist, but around these parts I hear “man, capitalism is awesome” (basically verbatim) and similar sentiments often enough that I’m not sure how we continue to survive living in Berkeley unscathed.

Though we sympathize with the existential risk school in the concern for catastrophe, we do not focus only on this narrow position. This partly stems from a humility about the limitations of human reason—to either imagine possible futures or wholly shape technology’s medium- and long-term effects.

I ask you to please at least try engaging with object-level arguments before declaring that reasoning about the future consequences of one’s actions is so difficult as to be pointless. After all, you don’t actually believe that: you think that your proposed path will have better consequences than the alternatives you describe. Why so?

Is your perspective something like:

Something like that, though I’m much less sure about “non-norms-violating”, because many possible solutions seem like they’d involve something qualitatively new (and therefore de-facto norm-violating, like nearly all new technology). Maybe a very superhuman TAI could arrange matters such that things just seem to randomly end up going well rather than badly, without introducing any new[1] social or material technology, but that does seem quite a bit harder.

I’m pretty uncertain about, if something like that ended up looking norm-violating, it’d be norm-violating like Uber was[2], or like super-persuasian. That question seems very contingent on empirical questions that I think we don’t have much insight into, right now.

I’m unsure about the claim that if you put this aside, there is a way to end the acute risk period without needing truly insanely smart AIs.

I didn’t mean to make the claim that there’s a way to end the acute risk period without needing truly insanely smart AIs (if you put aside centrally-illegal methods); rather, that an AI would probably need to be relatively low on the “smarter than humans” scale to need to resort to methods that were obviously illegal to end the acute risk period.

(Responding in a consolidated way just to this comment.)

Ok, got it. I don’t think the US government will be able and willing to coordinate and enforce a worldwide moratorium on superhuman TAI development, if we get to just-barely TAI, at least not without plans that leverage that just-barely TAI in unsafe ways which violate the safety invariants of this plan. It might become more willing than it is now (though I’m not hugely optimistic), but I currently don’t think as an institution it’s capable of executing on that kind of plan and don’t see why that will change in the next five years.

Another way to put this is that the story for needing much smarter AIs is presumably that you need to build crazy weapons/defenses to defend against someone else’s crazily powerful AI.

I think I disagree with the framing (“crazy weapons/defenses”) but it does seem like you need some kind of qualitatively new technology. This could very well be social technology, rather than something more material.

Building insane weapons/defenses requires US government consent (unless you’re commiting massive crimes which seems like a bad idea).

I don’t think this is actually true, except in the trivial sense where we have a legal system that allows the government to decide approximately arbitrary behaviors are post-facto illegal if it feels strongly enough about it. Most new things are not explicitly illegal. But even putting that aside[1], I think this is ignoring the legal routes by which a qualitatively superhuman TAI might find to ending the Acute Risk Period, if it was so motivated.

(A reminder that I am not claiming this is Anthropic’s plan, nor would I endorse someone trying to build ASI to execute on this kind of plan.)

TBC, I don’t think there are plausible alternatives to at least some US government involvement which don’t require commiting a bunch of massive crimes.

I think there’s a very large difference between plans that involve nominal US government signoff on private actors doing things, in order to avoid comitting massive crimes (or to avoid the appearance of doing so), plans that involve the US government mostly just slowing things down or stopping people from doing things, and plans that involve the US government actually being the entity that makes high-context decisions about e.g. what values to to optimize for, given a slot into which to put values.

- ^

I agree that stories which require building things that look very obviously like “insane weapons/defenses” seem bad, both for obvious deontological reasons, but also I wouldn’t expect them to work well enough be worth it even under “naive” consequentialist analysis.

- ^

Regrettably I think the Schelling-laptop is a Macbook, not a cheap laptop. (To slightly expand: if you’re unopinionated and don’t have specific needs that are poorly served by Macs, I think they’re among the most efficient ways to buy your way out of various kinds of frustrations with owning and maintaining a laptop. I say this as someone who grew up on Windows, spent a couple years running Ubuntu on an XPS but otherwise mainlined Windows, and was finally exposed to Macbooks in a professional context ~6 years ago; at this point my next personal laptop will almost certainly also be a Macbook. They also have the benefit of being popular enough that they’re a credible contender for an actual schelling point.)

I agree with large parts of this comment, but am confused by this:

I think you should instead plan on not building such systems as there isn’t a clear reason why you need such systems and they seem super dangerous. That’s not to say that you shouldn’t also do research into aligning such systems, I just think the focus should instead be on measures to avoid needing to build them.

While I don’t endorse it due to disagreeing with some (stated and unstated) premises, I think there’s a locally valid line of reasoning that goes something like this:

if Anthropic finds itself in a world where it’s successfully built not-vastly-superhuman TAI, it seems pretty likely that other actors have also done so, or will do so relatively soon

it is now legible (to those paying attention) that we are in the Acute Risk Period

most other actors who have or will soon have TAI will be less safety-conscious than Anthropic

if nobody ends the Acute Risk Period, it seems pretty likely that one of those actors will do something stupid (like turn over their AI R&D efforts to their unaligned TAI), and then we all die

not-vastly-superhuman TAI will not be sufficient to prevent those actors from doing something stupid that ends the world

unfortunately, it seems like we have no choice but to make sure we’re the first to build superhuman TAI, to make sure the Acute Risk Period has a good ending

This seems like the pretty straightforward argument for racing, and if you have a pretty specific combination of beliefs about alignment difficulty, coordination difficulty, capability profiles, etc, I think it basically checks out.

I don’t know what set of beliefs implies that it’s much more important to avoid building superhuman TAI once you have just-barely TAI, than to avoid building just-barely TAI in the first place. (In particular, how does this end up with the world in a stable equilibrium that doesn’t immediately get knocked over by the second actor to reach TAI?)

(I am not the iniminatable @Robert Miles, though we do have some things in common.)

I’m talking about the equilibrium where targets are following their “don’t give in to threats” policy. Threateners don’t want to follow a policy of always executing threats in that world—really, they’d probably prefer to never make any threats in that world, since it’s strictly negative EV for them.

But threateners don’t want want to follow that policy, since in the resulting equilibrium they’re wasting a lot of their own resources.

Note that this model moderately-strongly predicts the existence of tiny hyperprofitable orgs—places founded by someone who wasn’t that driven by dominance-status and managed to make a scalable product without building a dominance-status-seeking management hierarchy. Think Instagram, which IIRC had 13 employees when Facebook acquired it for $1B.

Instagram had no revenue at the time of its acquisition.

faul’s comment represents some of my other objections reasonably well (there are many jobs at large orgs which have marginal benefits > marginal costs). I think I’ve even heard from Google engineers that there’s an internal calculation indicating how what cost savings would justify hiring an additional engineer, where those cost savings can be pretty straightforwardly derived from basic performance optimizations. Given the scale at which Google operates, it isn’t that hard for engineers to save the company large multiples of their own compensation[1]. I worked for an engineering org ~2 orders of magnitude smaller[2] and they were just crossing the threshold where there existed “obvious” cost-saving opportunities in the 6-figures per year range.

- ^

The surprising part, to people outside the industry, is that this often isn’t the most valuable thing for a company to spend marginal employees on, though sometimes that’s because this kind of work is often (correctly) perceived as unappreciated drudge work.

- ^

In headcount; much more than 2 OoMs smaller in terms of compute usage/scale.

- ^

Nah, I agree that resources are limited and guarding against exploitative policies is sensible.

Maybe we should think about implementing InvertOrNot.

In general I think it’s fine/good to have sympathy for people who are dealing with something difficult, even if that difficult thing is part of a larger package that they signed up for voluntarily (while not forgetting that they did sign up for it, and might be able to influence or change it if they decided it was worth spending enough time/effort/points).

Edit: lest anyone mistake this for a subtweet, it’s an excerpt of a comment I left in a slack thread, where the people I might most plausibly be construed as subtweeting are likely to have seen it. The object-level subject that inspired it was another LW shortform.

My guess is that most don’t do this much in public or on the internet, because it’s absolutely exhausting, and if you say something misremembered or misinterpreted you’re treated as a liar, it’ll be taken out of context either way, and you probably can’t make corrections. I keep doing it anyway because I occasionally find useful perspectives or insights this way, and think it’s important to share mine. That said, there’s a loud minority which makes the AI-safety-adjacent community by far the most hostile and least charitable environment I spend any time in, and I fully understand why many of my colleagues might not want to.

I’d be very interested to have references to occassions of people in the AI-safety-adjacent community treating Anthropic employees as liars because of things those people misremembered or misinterpreted. (My guess is that you aren’t interested in litigating these cases; I care about it for internal bookkeeping and so am happy to receive examples e.g. via DM rather than as a public comment.)

Curated. I like that you demonstrate failure along multiple dimensions, each of increasing signal:

generally poor scientific methodology, conflicts of interest, and sketchy marketing (base rate of proposed medical interventions with these qualities being effective is low)

claimed mechanism of action doesn’t seem to be present in the actual product (it doesn’t matter if the science checks out if the active ingredient isn’t in the product)

claimed mechanism of action can’t actually work for more basic biological/physical reasons (it doesn’t matter if the active ingredient is in the product if it can’t actually do the thing)

The last one isn’t totally sufficient, since sometimes things work for reasons other than those claimed by proponents, but overall this is a pretty convincing analysis.

Because the bill only prevents employers from forbidding employees from reporting those issues to the AG or Labor Commissioner?

Leaning what human values are is of course part of a subset of learning about reality, but also doesn’t really have anything to do with alignment (as describing an agent’s tendency to optimize for states of the world that humans would find good).