Confused Attractiveness

Crossposted from Optimized Dating.

I.

Imagine that you are a human xeno-sociologist studying the society of insectoid aliens on another planet. To you, they all look alike the same way two ants look alike. Yet when talking about each other, they often use words that translate closely to “beautiful”, “attractive”, “plain” and “ugly”, indicating that they see an aesthetic quality in each other that you don’t see. How do you learn which specific insectoid individuals are attractive and which ones are not?

The Ant and the Grasshopper, J. J. Grandville, 1838 (!!!)

First thing you could try is to take photos of many aliens – let’s say a hundred of them. Then you make a survey which asks a simple binary question under each photo: “Is this individual attractive? Y/N”. You distribute the survey to a large group of aliens, collect the responses and arrange the photos from the one with least Y’s to the one with the most. You designate the first 10 aliens as “10th percentile rank”, next 10 as “20th”, and so on until the most attractive alien in your sample, who gets “99th”. Now you can compare the ranks of any two aliens in your study and see which one is more attractive than the other.

You proceed to gather data on attractiveness in more elaborate ways, not just with surveys but looking for revealed preference as well—for example, measuring exoskeleton conductance response when presented with different alien faces, or measuring tips that the alien waiters get. Crucially though, two facts hold constant throughout your studies:

Attractiveness is determined by conscious or unconscious reactions of other individuals (binary choice/conductance/tipping).

Attractiveness of an individual can be expressed as a percentile rank among all the other individuals in a study.

The data looks nice, but what if you need to check the attractiveness of an alien that’s not in your ranked sample? It’s expensive and cumbersome to run a full study with a large population each time you want to assess whether some specific alien you meet is attractive or not. It would be great to learn how to tell apart beautiful aliens simply by looking at them. Is there a way to do that?

You try to extract a set of features associated with each attractiveness rank. You discover that individuals in top attractiveness ranks have longer antennae and bulging thorax, while lowest-ranked aliens have small claws and large mandibles. With years of experience, you can reliably tell whether the alien is attractive to other aliens just by looking at four body parts. Based on your findings, you publish a four-feature alien attractiveness model, which highly correlates with survey rankings (r = 0.53).

Does this model measure attractiveness though? Whatever it measures, it seems to have very different properties from the attractiveness determined by surveys.

Attractiveness is determined by a set of objective morphometric measurements which were found to most closely correlate with attractiveness data.

Attractiveness of an individual can be expressed as a deviation from the “ideal score”, with the most beautiful possible combination of features having a deviation of 0.

Anyway, seems like the expedition was a success! After you return back to Earth from your trip, you unexpectedly bump into a stunningly attractive stranger reading your favorite book. After a few words, you get her contact number and invite her on a date. How did you know this stranger was attractive? You didn’t find her photo in a top percentile of a beauty survey. You didn’t run her morphometric data through a beauty-determining algorithm. You simply got some sort of… aesthetic feeling in your mind, not intrinsically tied to any specific quantifiable metric.

It seems like the way you determine attractiveness in your day-to-day life is completely different from what you were studying on an alien planet:

Attractiveness is determined by your brain’s subjective reaction to sensory stimuli it receives.

Attractiveness of an individual can be expressed with subjective qualitative statements such as “He makes my heart flutter” or “She is not my type”.

To sum up, it seems like there are three different sources that can provide information about someone’s attractiveness:

1. Introspection provides instant subjective assessment of attractiveness, but it’s not inherently quantifiable and does not necessarily generalize.

2. Population study aggregates subjective assessments from multiple people in the study population, allowing you to find the most and least attractive people among a small set of samples. It’s however slow and expensive to run, and different study designs will give different results. It also doesn’t tell you anything about people who weren’t in the study sample.

3. Morphometric analysis gives an attractiveness score based on a set of objective criteria (height, waist-to-hip ratio etc). It’s quick once you know what to look for, but even the best models produce middling correlation with study results.

Crucially, these are three different things. There are people you find attractive that the society in general doesn’t. There are people society finds attractive that you don’t. There are unattractive people who score highly on objective morphometrics and attractive people who don’t.

So, how do we make sense of this mess?

II.

Let’s start by tabooing the word “attractiveness”. Instead, we will use three new words, one for each source of information in our arsenal.

1. Appeal is a subjective feeling you get when looking at an attractive person.

People with high appeal stir feelings of desire inside you. People with low appeal will make you recoil in disgust.

2. Desirability is a rank people get on a study measuring aggregated subjective responses.

People with high desirability produce positive reactions in other people. People with low desirability get negative responses.

3. Flawlessness is adherence to a set of empirically deduced objective beauty measurements that try to predict survey results based on morphometrics.

People with high flawlessness have a specific height, facial symmetry, body proportions and muscle definition. People with low flawlessness deviate from this ideal.

To make an analogy with music, tracks that are not Appealing wouldn’t make it into your playlist, tracks that are not Desirable wouldn’t make it to Top 40, and tracks that are not Flawless probably sound out of tune or have unconventional time signature.

So, how do they stack together? Let me go over each of 8 possible combinations and do my best to imagine what response they would provoke.

High Appeal, high Desirability, high Flawlessness

This person fits standard beauty norms, and you find them attractive as much as most people do.

Low Appeal, high Desirability, high Flawlessness

“Too basic for my taste”. This person is widely considered an icon of beauty, but for some reason you’re not into the prevailing beauty standard, so you’re not excited to get together with them.

High Appeal, low Desirability, high Flawlessness

“How come I don’t have competition?”. You adore this person, but you can’t understand why aren’t they more popular with the opposite sex.

High Appeal, high Desirability, low Flawlessness

“There’s something about her, can’t quite put a finger on it”. An unexplainable charm, a trendmaker defying expectations.

High Appeal, low Desirability, low Flawlessness

This is an “ugly” person who you fall for anyway. Perhaps you have a very specific and rare turn-on?

Low Appeal, high Desirability, low Flawlessness

“What does anyone find in him??”. This person is a sex symbol for no obvious reason to you.

Low Appeal, low Desirability, high Flawlessness

“Wow, the character creator tool in this game sucks. Whatever sliders I tweak, it still looks awful”. This person is off-putting in a way that’s not legible or quantifiable, and it’s hard to pinpoint what needs to be corrected.

Low Appeal, low Desirability, low Flawlessness

This person is unattractive in a really obvious way, for you as much as for everyone else.

What lessons can we draw from looking at these combinations?

When Appeal and Desirability are the same sign, you have “vanilla” preferences. When they are opposite, you have an “uncommon taste” in people’s appearance.

When Desirability and Flawlessness are the same sign, the Desirability is easily legible. When they are the opposite signs, it’s “hard to put a finger” on the determinant of the Desirability result.

Machine learning allows for automated high-confidence Desirability measurement, skipping the step of picking morphometric factors to construct the Flawlessness model.

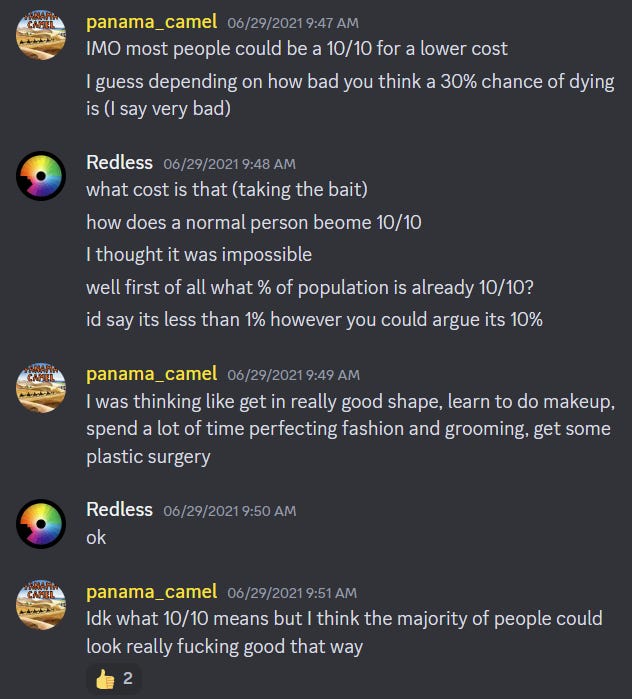

Many disagreements about attractiveness result from people using different definitions of “attractiveness”, for example one person talking about Desirability while another talks about Flawlessness. This can happen even when no one says the word “attractive” at all! The confusion can be created just by using the 1–10 scale, which can refer to any of the three types of attractiveness.

Consider the case when your interlocutor looks at a picture of a celebrity and assigns them a 1-10 number without looking up any data or doing any measurements or calculations. What is going on in their mind?

People who use 1-10 scale as measurement of Appeal can easily replace numerical score with letters such as in tier lists (S=10, A=8-9, B=6-7…). The numbers in this case are simply a made-up score that doesn’t actually correspond to any data and can’t be derived by calculation (similar to 1-10 pain score used in emergency clinic). They would not be vocally disagreeing with people who give completely different scores to the same people—after all, this is not a disagreement of fact, but merely the difference of taste, like if someone enjoys different music than you do.

People who use 1-10 scale as a measurement of Desirability would probably agree that there are as many 10’s as there are 1’s and 5’s out there, or at least that their ranking system can be divided into statistical deciles. When assigning a number, these people essentially run a prediction like “If I asked 10 people whether they would hook up with this person, X% would say yes”, and they count on their experience to predict the “correct” number (which then rarely, if at all, gets tested with actual survey data). These people can say seemingly nonsensical stuff like “She’s a 10, but I’m not into her” and be correct.

People who use 1-10 scale as a measurement of Flawlessness might use the infamous Gigachad model as an example of a 10⁄10 man, despite not having any data on whether women consider him attractive or not. Then any perceived physical “flaws” or deviations would reduce the score. The statements like “She could be a 10, but her shoulders are too broad, and the jaw looks too masculine, so let’s make it an 8” would be an example of this approach.

Coming back to the word “attractiveness”, how to tell what do people talk about when they mention it? Here are a few examples.

People are talking about Appeal if:

They’re excited about getting romantically involved with a partner

They’re filling a survey about attractiveness

They’re casting actors for their movie to fit their creative vision

People are talking about Desirability if:

They’re casting actors for their movie to maximize ticket sales

They’re talking about someone being “conventionally attractive”

They’re choosing which photo to put on their dating app profile

People are talking about Flawlessness if:

They’re casting a fashion model to showcase designer outfits

They’re a jury member in a bodybuilding contest

They’re filtering a large pool of potential partners by e.g. height

Hopefully this paradigm will be helpful in resolving arguments about attractiveness, so that we can focus on arguing about more important things, like whether anything is ever consensual.

Tangential to the main point of your post, but:

Clearly no; if the correlation is 0.53, then that means 72% of the factors influencing attractiveness are not captured by the measure.

Assuming your results are causal, you’ve found some major contributors to attractiveness, and that’s definitely worth something in itself, but it’d be inaccurate to market it as capturing attractiveness in general.

I think what you’re calling Desirability conflates two categories: average Appeal and conventional attractiveness? Imagine a small majority of insects personally prefer longer antennae, but also that this preference is somewhat embarrassing and short antennae are widely recognized as the more attractive shape. While you’d classify all of these under Desirability, movies would cast short antennae leads to maximize ticket sales, non-hookup-focused dating app pictures would go for poses that shorten the antennae, and tycoons seeking trophy-spouses would go for the fashionably short.

One problem I see with your insect alien example, which also, in a much greater way, influences human attractiveness, is that there are not just four, or five, or a dozen of physical attractiveness factors, but hundreds of them. And each of these factors influences other factors in different ways, for example:

height on a man is considered attractive

low body fat on a man is considered attractive, but;

a combination of too much height and too little body fat would be unattractive.

My take is there are hundreds, even thousands of traits that fall under “Flawlessness” but they play very weirdly against each other, and thus Appeal is born; a personal subconscious opinion on what sets of traits one likes most.

What is also missing from your analysis, is Beauty-Appeal Vs Sex-Appeal. Some traits trigger our aesthetic appreciation, and some trigger our raw sexual appetite, and not only are these not the same traits, but sometimes opposite ones.

I would define Sex-Appeal as a set of traits, physical and behavioral, that make the person seem:

relatively easy to seduce (for me), also known as DTF (down to fuck)

suggesting they would be good at sex

suggesting their body would feel nice to touch

vaguely related to strong Secondary Sexual Characteristics

Meanwhile, Beauty-Appeal are sets of purely aesthetic Flawlessness traits, that do not correspond to the above points at all, but show symmetry, golden ratio, aesthetically striking color palette etc. The make a person a perfect model, someone you would love to take pictures of, paint or draw, rather than get raunchy with.

I would even take it further, many of the Beauty-Appeal traits take away from Sex-Appeal, because some of them are signifiers of innocence, youth, or vaguely stand-offish perfection, that make the person seem like they would not be DTF. We subconsciously disengage from thoughts about having sex with such a person, regardless whether or not these traits truly signify their DTF.

Some examples:

Melodic, high female voice: beauty

raspy, low pitched female voice: sexy

Flawless skin: beauty

Tattoos and “cool” scars: sexy

hairless male chest: beauty

hirsute male chest: sexy

perfectly sized medium breasts: beauty

oversized breast: sexy

Absolutely. Some are simple, legible, and included in our morphometric models explicitly as measurements (height, skin color). Some are highly compound, perceived on a subconscious level and can only be modeled via data science (“aggressiveness”).

Yes, for each flawlessness model there’s a maximum point with no flaws, and deviating from this point would lower your score in this model. You can imagine your example as a two-dimensional graph with a maximum value at some combination of (height, body fat), and deviating from that combination would lower the score.

How many traits are there in the best-performing flawlessness model nowadays?

I’d describe sequence of events in another order: Appeal is born first, Desirability is an approximation of Appeal, and Flawlessness is a proxy of Desirability. Each one is more usable but also more detached from reality than the last.

Agreed that analyses of this word/concept are confused. Unfortunately, this doesn’t deconfuse things, it just adds some epicycles to the confusion.

You’re right that there are multiple dimensions to what it might mean to be “attractive”, but you’ve missed the complexity of individual judgements, aggregated non-linearly to social agreement within a given subculture.

Whether someone has a symmetrical face and clear, smooth skin is somewhat objective. How to notice that, weight it against other attributes, and give praise for it is both individually decided and socially constructed. Avoiding the confusion means acknowledging the non-objective nature of the evaluation, both highly variable among individuals and normalized among cultures.