Quick evidence review of bulking & cutting

Epistemic status: fairly fast non-comprehensive literature review by a non-expert

Content warning: I advise against reading this if you believe you have an eating disorder

My ideal body aesthetic would be to have defined muscles and low body fat. Maybe this is also true of you. Maybe you’ve heard of cycling between seasons of building muscle (bulking) and losing fat (cutting) as a way to achieve that aesthetic. Should you?

Theory

It is easier to add muscle when on a caloric surplus[1] (more on that citation later). The theory is that it’s so much easier to build muscle this way, that you should spend several months intentionally eating more calories than you need, and accept that you’ll probably gain some body fat as well. But not to worry, you can then spend some months eating fewer calories than you burn in order to reduce your body fat percentage. Chasing these two hares separately putatively leads to a better result along both dimensions than a steady state.

In addition, there’s a natural advantage to this approach from the dynamic where you care more about the low body fat percentage during the summer, where your muscle definition is more apparent.

Quick notes:

You definitely want to be doing resistance training (weightlifting) the whole time. Because that’s the primary way to build muscle mass, and to avoid losing muscle when you’re cutting.

I’ll assume that you are moderately physically fit — you’re not brand new to weightlifting, but you’re also not particularly close to body-builder levels of jacked.

It’s definitely possible to cut body fat below healthy levels. When I’m talking about low numbers I’m aiming for I’m thinking of something like 10%-ish, though I haven’t really looked into this.

Evidence from bodybuilders

One piece of evidence is that most (maybe ~all) body builders do this.[2] Body builders have a similar goal to us — I wouldn’t go as far as they go, but building muscle definition is the name of their game, and they certainly achieve it. I would downweight this evidence on the basis of several factors that lead me to believe that the superiority of this technique might fail to generalize:

Bodybuilders have a competition season where they want to have a very low body fat percentage, often pushing down below sustainable levels. (I’ve seen numbers around 4%.)

The very low levels of body fat targeted by body builders is sufficiently low to interfere with sleep and hormone regulation, and I wouldn’t be surprised if it interfered with muscle gain.

Body builders have a lot of muscle and those muscles are quite used to resistance training. Building muscle on top of that base is quite hard.

Theory part 2

Let’s dig more into the actual counterfactual. We have 12 months in front of us, should we cycle our caloric intake, or… what? We’d like to end up at the end of the year with more muscle mass, and less body fat. To do so (with, as best I can tell, a connotation of keeping a steady caloric intake) is called body recomposition. If you only want to cut a few percentage points of body fat, but want to gain 10s of pounds of muscle, then you’d probably eat a slight surplus. If you want to mostly lose body fat, then you’d run a slight deficit for the year. You could adjust this amount empirically based on your progress.

To figure out which approach is better, let’s make some assumptions:

You spend the same amount of time bulking as cutting

You neither gain nor lose muscle mass while cutting.

Given these assumptions, the muscle gain you need to achieve from your bulking needs to be twice the amount you’d achieve from your steady diet over the same period, to compensate for the time period where you’re not gaining muscle. We’ll assume that we’ve tuned both diets to end up at the same body fat percentage.

Evidence from one study

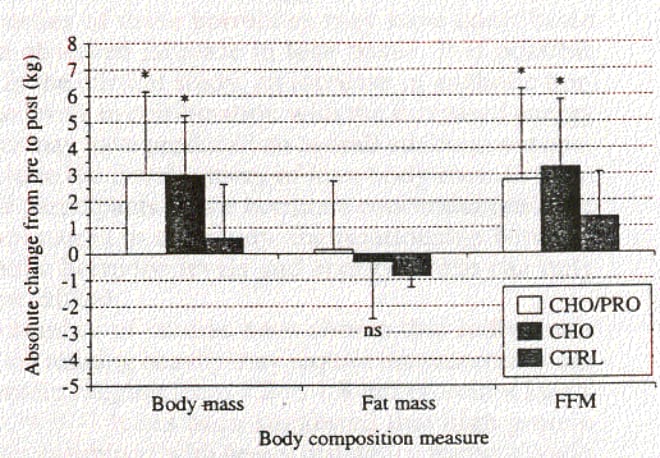

I’m quite surprised at how few attempts I’ve seen at measuring the difference between these approaches. The question of how effective overfeeding is at building muscle mass seems quite basic to sports science, but my review[3] only turned up one study.[1] Rozenek et al. recruited 73 participants (male, mildly active) and divided them into 3 groups. All groups performed resistance training and were instructed to continue eating their regular diet in addition to a supplement. One group got a 2000 kcal shake of protein & carbohydrates. Another group got the same 2000 kcal of carbs only. The final group was a control. All three groups gained muscle, as you would expect. Somewhat surprisingly both the supplement groups gained about the same amount of muscle. The question for us is how much more the supplemented group gained compared to the control. They did gain more, and the difference was significant, but the error bars are sufficiently wide that a precise comparison is impossible. However, the gains from the supplemented group were about double that of the control.

The most I’m willing to draw from this is that the benefits of bulking appear to overlap the bar that they need to hit.

Conclusion

My takeaways from this research are sadly quite equivocal. I’m forced to make the boring suggestion that you should go with whatever approach you think would be the best match for your personality. Some factors I’d consider:

Cutting is famously quite unpleasant!

On the other hand, if you tend to gain body fat unless you are focusing on dieting, you need to diet for a shorter period of time when cycling.

Do you care significantly more about your body fat percentage in the summer?

Which do you think would be easier to stick to?

I specifically would warn that it may be psychologically easier to stick with a bulking diet than a cutting one, with obvious implications.

Are you worried about an eating disorder? Bulking and cutting appears to be a risk factor.[4]

If I expected this conclusion to be wrong it would be because the primary study I rely on above, as well as the studies that I reference to show that body recomposition is possible, tend to rely on studies of subjects fairly new to resistance training. Potentially the audience I have in my for this research (myself, other gym-goers) are far enough along the diminishing returns to resistance training without excess calories that the benefits to bulking for that type of person is significantly more than 2x as good as a constant diet.

Personally, I have been through about 3 cycles of bulking and cutting, and think it works well for me. This investigation has made me more reluctant to recommend it. Based on the interesting and thus-far-uncited Slater et al.[5] I’m more optimistic about getting the benefits of a smaller surplus (~500k cal/day) than I’d guess I usually get during bulking season, which probably will change my behavior this fall.

- ^

R. Rozenek, P. Ward, S. Long, J. Garhammer (2002). Effects of high-calorie supplements on body composition and muscular strength following resistance training. The Journal of sports medicine and physical fitness. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12094125/

- ^

L Mitchell, D Hackett, J Gifford, F Estermann, H O’Connor. (2017) Do Bodybuilders Use Evidence-Based Nutrition Strategies to Manipulate Physique? Sports (Basel, Switzerland). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5969027/

- ^

A quick note on how I did my review: I did a fairly quick (several hour) dive through papers in some search results, looked at promising citations of those papers, and repeated one level deeper. At the end someone pointed me to elicit.org, which failed to turn up anything comparably good.

- ^

KT Ganson, ML Cunningham, E Pila, RF Rodgers, SB Murray, JM Nagata. (2022). “Bulking and cutting” among a national sample of Canadian adolescents and young adults. Eating and weight disorders. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9462603/

- ^

GJ Slater, BP Dieter, DJ Marsh, ER Helms, G Shaw, J Iraki. (2019). Is an Energy Surplus Required to Maximize Skeletal Muscle Hypertrophy Associated With Resistance Training. Frontiers in nutrition. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6710320/

Thanks for writing this up! I wonder how feasible it is to just do a cycle of bulking and cutting and then do one of body recomposition and compare the results. I expect that the results will be too close to tell a difference, which I guess just means that you should do whichever is easier.

I would also expect extraneous details like, “got sick and fell of the wagon” or similar to add significant noise. And with only one data point each, it’d be hard to know the variance to use. I’m guess I’d trust this study more?

I’ve been working on making Elicit search work better for reviews. Would be curious for more detail on how Elicit failed here, if you’d like to share!

To be clear I don’t know what I’m doing really. I do think that it failed to get the precise thing I was looking for though.

thanks for writing this — also, some broad social encouragement for the practice of doing quick/informal lit reviews + posting them publicly! well done :)