What are the results of more parental supervision and less outdoor play?

Crossposted from Otherwise

Parents supervise their children way more than they used to

Children spend less of their time in unstructured play than they did in past generations.

Parental supervision is way up. The wild thing is that this is true even while the number of children per family has decreased and the amount of time mothers work outside the home has increased.

(What’s happening in France? I don’t know.)

Western children are typically not allowed to go as far from their home unattended as in past generations. This map of the shrinking walkshed over four generations is anecdotal but I think typical — ask any older person about when they walked to school unsupervised.

More supervision means less outdoor play

Most of this supervision is indoors, but here I’ll focus on outdoor play. Needing a parent to take you outside means that you spend less time outside, and that when you are outside you do different things.

It’s surprisingly hard to find data on how much time children spend playing outside now vs. in past generations. Everyone seems to agree it’s less now, and you can look at changing advice to parents, but in the past people didn’t collect data about children’s time use.

“A study conducted in Zurich, Switzerland, in the early 1990s . . . compared 5-year-olds living in neighborhoods where children of that age were still allowed to play unsupervised outdoors to 5-year-olds living in economically similar neighborhoods where, because of traffic, such freedom was denied. Parents in the latter group were much more likely than those in the former to take their children to parks, where they could play under parental supervision. The main findings were that those who could play freely in neighborhoods spent, on average, twice as much time outdoors, were much more active while outdoors, had more than twice as many friends, and had better motor and social skills than those deprived of such play.” More

Adolescent mental health has worsened

This year’s Youth Risk Behavior Survey looked pretty bad about the wellbeing of American adolescents.

People squint at correlations, and theories include:

Social media and phone use

Political messages of helplessness and despair

Play used to be more dangerous

My grandfather was a small-town newspaper reporter in the early 20th century. He wrote “I remember a newspaper story about a boy who suffered a broken arm when, as the account read, he ‘fell or jumped’ from a low shed roof. Nobody knew whether kids fell or jumped because they were usually doing one or the other.”

Our next-door neighbor had a twin brother who drowned at age 6 in the river while playing boats with an older child (in 1950s Cambridge MA, not a remote rural area).

Our housemate grew up on a farm, where he and his friends would amuse themselves by cutting down trees while one of them was in the tree. “It was fun, but there were some scary times when I thought my friends had been killed.”

Playground injuries are . . . up?

I was expecting that more supervision meant fewer injuries. This doesn’t seem to be the case at playgrounds, at least over the last 30 years.

From a large study of US visits to emergency rooms related to playground equipment:

Maybe children are spending time at playgrounds if they’re not playing in empty lots and such? But here’s children injured at school playgrounds (which are presumably seeing similar use over time) in Victoria, Australia. I don’t think this is just because of wider awareness of concussions or something, because even in the 80s you still got treated at a hospital if you broke your arm.

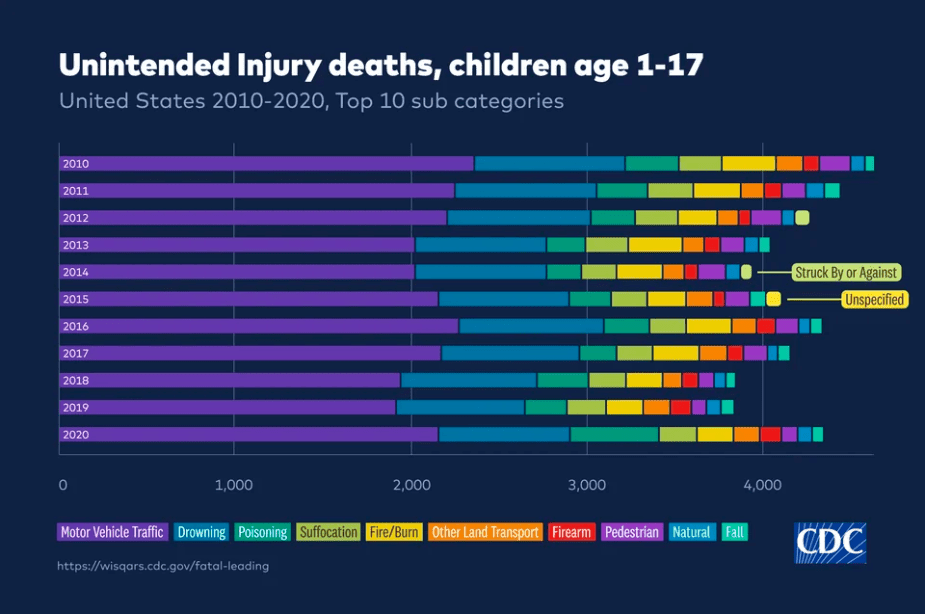

But deaths from accidents are down

US accidental deaths of children age 10-19:

UK in the 80s and 90s, aged 19 and under:

The types of accidents that kill children and teens are mostly cars and drowning.

Most of the motor vehicle deaths are while riding in cars, which is a different topic. What about while children are playing or walking around?

As parental supervision has increased, child pedestrian deaths have fallen. Some of this may be because of better pedestrian infrastructure like crosswalks and speed bumps. But I suspect much of it is an adult being physically present with children when they’re near streets.

Trends in pedestrian death rates by year, United States, 1995-2010, children ages 19 and under. The article says 90% of injured child pedestrians are unaccompanied by an adult at the time of the injury. But this is mostly teenagers, so it’s not surprising they’re unaccompanied.

Drownings are also down over this time, probably partly because of rules about fences around pools and partly because of more supervision. The drownings of babies under 1 is mostly in bathtubs, so I expect the gains there are largely from more awareness and more supervision within the home.

Some personal takeaways

Whatever we’re doing in supervising children at playgrounds is not reducing injuries. We might as well let them play in a more traditional, unstructured, unsupervised way — at least in spaces where they won’t be hit by cars.

Car traffic still seems worth worrying about. The most dangerous thing I see kids doing in our neighborhood is riding scooters on the sidewalk and zooming across intersections without checking for cars.

When we’re near water, I take drowning risk seriously.

Boys play outside more than girls, and have higher injury rates than girls. If I had boys, or kids who were generally more into risk-taking, I might worry more about serious injuries. But I’d also worry about stifling them too much or not letting them develop common sense from minor injuries.

I haven’t looked at the evidence on bike helmets for kids, but they seem like a good idea. After a sledding accident involving a brick wall, we also use them for stuff like sledding and climbing big rocks.

More prosaically, warm enough clothing means we spend more time outdoors. Both kids and adults in our family wear snowpants a lot in the winter, which makes outdoor play much more viable in New England.

You can’t single-handedly recreate the 1960s

One friend said that after reading about historical rates of parental supervision, she’d take her preschooler to the park and say, “Have fun, I’ll be over here reading my book.” I also try to channel the older laid-back approach to supervision of outdoor play.

But you can’t create the social environment that existed when all the kids had less supervision. This isn’t just the “someone will call the police” fear; it’s more prosaic too. At some point other parents will view you as suspect and won’t let their kids play with yours, which defeats some of the purpose.

Some methods we’ve used:

A lot of it was luck to be in a pretty walkable neighborhood with well-used playgrounds. Courtyard apartments (or other spaces where kids don’t have to cross a street to access play space) seem especially good for letting urban kids play unsupervised at a younger age.

Supervision theater: when my kids were preschoolers and playing at the park while I was present but not hovering, other parents would start looking around to see if these children were alone. I’d periodically announce things like “Your water bottle is here if you want it,” and then the other adults wouldn’t bother us.

Moderating: “You can climb that tree, but one person at a time.”

Teaching street-crossing with toddlers and older kids

Walkie-talkies: They’re quite a bit better than in past decades; they reach a quarter mile and mean both we and the kids have more freedom of movement. We can take one kid to the nearby park while another one stays home, able to radio us. We trust our kids to play at the park before we trust them to cross the street, so they sometimes play at the park and radio home when they want us to walk them home.

Rehearsing with my kids what they’d say if a grownup asks why they’re alone: “My parents said it’s ok for me to be here.”

Making friends with other families with more free-range kids. We met one such family (recent immigrants from Europe) because they had the only other five-year-old we’d seen playing on the bike path with no adult immediately present.

More ideas from Peter Gray

Visits to emergency rooms might not be down if parents are e.g. panicking and bringing a child to the ER with a bruise.

True. The “arm fracture” one on the Victoria chart seems pretty concrete, though.

I know we took our kid to the emergency room around four months because we couldn’t find the button that had come off his shirt, we assumed he ate it, and the poison control hotline missheard button as button battery. That sequence probably wouldn’t be in the statistics in the 80s!

Another method we used was that before letting the kids be at park their own I talked with a lot of the other park parents. These conversations usually started with me asking something like “How are you thinking about when kids are ready to be at the park on their own?”, and then touched on a lot of things including what I was planning, walkie talkies, etc. People were neutral to supportive; no one seemed to think it would be irresponsible or unreasonable. This was useful both for reducing the chance that I had misjudged the situation, and reducing the risk that other people would call the cops (Imagined: “Is anyone here with those kids? I’m worried about them.” “Oh, those are Jeff and Julia’s kids, I talked with Jeff about this and he knows they’re here. They have a walkie talkie if they need him, and he’s checking on them every so often.”)

We recently gave our 9-year old a ‘kid license’ attached to a tile to take around when he runs errands. He’s had not trouble with anything other than one store refusing to sell him cookies on the basis that they didn’t think his mother would approve. He really loves the independence. I’ve given him a cell-phone in a fanny-pack to take when going someplace new, but he doesn’t want to take the cell phone most of the time. Of course we can’t do this with our 6-year old, both because he is clearly not mature enough, and even if he was, I’m pretty sure strangers would object.

I assume you live in the US or Canada. The fact that you feel the need to give the 9-year-old a kid license (the tile is smart!) I think points to societal issues to do with norms and structure that lead to the sort of effects described in the OP.

US and Canadian cities (and much of Europe and the developing world that designed their cities by the West’s example) are generally not designed in a way that is friendly towards kids exploring and existing in the world safely.

I don’t mean ‘safely’ as in ‘they might fall down and scrape their knee or get lost’, I mean ‘safely’ as in ‘they might get struck by a driver going 40mph while staring at their phone as they barrel down a stroad’ or ‘they need to walk 3 miles to get to the nearest convenience store or park’.

It’s easy to find a number of examples of parents being disciplined or even arrested for allowing their children to walk to school, the store, or the park. To allow a child outside without guidance is considered gravely irresponsible by western society at large in a way that really isn’t healthy or helpful for promoting independence, in my opinion.

https://reason.com/2023/01/30/dunkin-donuts-parents-arrested-kids-cops-freedom/

https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2015/04/13/parents-investigated-letting-children-walk-alone/25700823/

https://www.cnn.com/2014/07/31/living/florida-mom-arrested-son-park/index.html

In Japan there’s a cultural rite of passage (usually in smaller towns, it seems) where children sometimes as young as 3 or 4 are sent on an errand, usually to go to the store and pick up a few things, or visit a family friend and retrieve something. There’s a Netflix series documenting a slightly more staged version of this, called ‘Old Enough!’. It’s very cute.

Here’s another potentially interesting article regarding this, from NPR, about playground safety:

https://www.npr.org/sections/13.7/2018/03/15/594017146/is-it-time-to-bring-risk-back-into-our-kids-playgrounds

I hope one day we can organize our society in a way in which kids can experience safe amounts of risk and develop into capable human beings. Thanks for doing your part.

While I agree that society is too far in the direction of not letting kids do things independently, I think it’s easy to think the status quo is worse than it actually is. I think these examples of Child Protective Services (CPS) making the wrong call are pretty bad, and I agree they’re partly “society considers letting kids be alone outside irresponsible” but also “CPS has a lot of discretion” and “if you make a lot of calls some of them will be wrong”.

Also, in a survey I ran the median age for when my sample thought a typical child in their area could be ready to play at a playground unsupervised was 8.4y. When you say “child outside without guidance” it’s not clear whether you’re thinking 4, 8, or 12.

After my kid was old enough to watch out for cars, he basically got free rein of our neighborhood. I also got him a cell phone early, so that he wouldn’t get lost, and we can communicate should we need the other. He has friends around the neighborhood, and I know most of their parents.

I really haven’t experienced other parents being overly concerned. Typically they are playing together, and the kids are old enough to manage themselves. My son is 13, so he’s almost past the point where anyone is going to blink at him walking alone, but I was always prepared to challenge anyone who didn’t think that he could manage.

One big change from when I was a kid is that my son can socially play video games way easier/more effectively. As a result, he’s more likely than I was to be playing video games, because they have way better communication tools. He doesn’t ride a bike like I did, and I think that a part of the reason is that he’s able to be social and play with his friends, all without leaving his house. If I didn’t ride my bike, I just wouldn’t see my friends.

I’m skeptical of these trends, or at least in the causal links implied here. The world is a bit more complex, and we have different tools, but I don’t think things are so radically different. My folks didn’t have the option of buying me a cell phone when I was a kid, but I’m sure would have had they been available. If Roblox was a thing when I was a kid, I likely would have played with my friends on there (technically around my folks) rather than biking 1.5 miles to my friend’s house. I didn’t have to worry about a global pandemic, nor did I grow up concerned about a changing climate. The internet wasn’t a thing. Heck, mental healthcare was practically taboo.

I think that the kids are going to be just fine. They have unique challenges, but they also have better tools to meet them. While I also believe in free-range parenting, my son’s friends whose parents prefer a more supervised style are great kids too.

What age was this, approximately?

I could imagine someone writing this about a 6yo or a 12yo.

Technically it would have been when he was 4-5, but he didn’t do a lot of exploring at that age. It wasn’t until later that he’d go off on his own more confidently. I see those years like him building up his confidence.

If we’re venturing into historically unprecedented changes in child upbringing either way, then it might be good to keep in mind that children spending time with other children is important for developing social skills in preparation for harsher social environments later on, but introspection and time spent talking with smart adults/tutors might result in substantially improved intelligence by the time they become adults.

As gaining approval from other parents becomes increasingly costly to the children themselves (due to other parents hovering and expecting you to consistently hover), it might be a good idea to just reduce stuff (including playdates and birthday parties) that require costly investment in getting other parent’s approval.

Plus, other kids will basically impose their phones and tablets on your kids, notably games and services like TikTok and Youtube (kid version) and intensely attention-optimized repetitive mobile games which are far more harmful than Minecraft (which Kelsey Piper claimed her friend’s kids generally preferred over any other activity).

Curated. I really liked reading this combination of big picture stats and practical experience with giving kids independence, and I think others will like reading it too. (It was especially fun to read with lots of pictures.)

The main thing, for me, is not that other parents will view us as suspect, but just that other kids are less likely to be there. My kids don’t want to just go out and run around because the other kids aren’t out there to run around with.

This depends a lot on where you are. If our kids go over to the neighborhood park on a nice day there’s a better than even chance that one of their friends are there.

They’ll also go over an knock on friends doors.

The site freerangekids has a map depicting an (anecdotal) decrease in childhood roaming over four generations. Not exactly hard data, but gestures at something obviously true.

Slightly adjacent to your post, but felt worth mentioning

Thanks, adding!

There’s a guy called Rafe Kelley on youtube who has a fairly good answer to this, which I’m going to attempt to summarize from memory because I can’t point you toward any reasonable sources (I heard him talking about it in a 1h+ conversation with everyone’s favourite boogeyman, Jordan Peterson).

His reasoning goes thus:

1.) We need play in order to develop: play teaches us how to navigate Agent—Arena relationships

This speaks to the result of playground injuries increasing despite increased supervision—kids aren’t actually getting to spend enough time playing in the physical Arena, their capability to navigate it is underdeveloped because of excess indoor time and excess supervision.

2.) We need rough play (e.g. play fighting), specifically, to teach us a whole bunch of capabilities around Agent—Agent—Arena relationships; conflict, boundaries, emotional regulation are all, Rafe argues, rooted in rough play.

Through rough and tumble play, we learn the physical boundaries between agents. We learn that it hurts them, or us, when boundaries are crossed. We learn where those boundaries are. We learn to regulate our emotions with respect to those boundaries.

These are highly transferable, core skills, without which human development is significantly stunted.

It concerns me that the best thing the education system ever did to teach negotiative social skills was leaving kids to their own devices. I think if we ackowledge the importance of conflict play, we can build play environments that would foster presently exceedingly rare levels of social robustness: https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/bF353RHmuzFQcsokF/peacewagers-so-far

“This speaks to the result of playground injuries increasing despite increased supervision—kids aren’t actually getting to spend enough time playing in the physical Arena, their capability to navigate it is underdeveloped because of excess indoor time and excess supervision.”

Anecdotal evidence from yoga and movement teachers would offer tangential support for this. They describe in children (and adults!) a trend to reduced somatic intelligence, core strength, proprioceptive awareness, and ability to assess risk.

Growing up with overprotective parents profoundly shaped my perspective, aligning closely with the author’s views. I believe in the importance of unsupervised free play for my children, offering them ample opportunities while also gently encouraging them to step out of their comfort zones.

In discussing this approach with friends, I was surprised to discover many held a firm stance on not letting their children out of sight until they’re 15. This prompted me to conduct a survey on parental attitudes towards children’s independence, such as biking to a store or taking a bus. The results were eye-opening: a majority of parents that responded wouldn’t grant such freedoms until their children are old enough for a driver’s license.

The LessWrong Review runs every year to select the posts that have most stood the test of time. This post is not yet eligible for review, but will be at the end of 2024. The top fifty or so posts are featured prominently on the site throughout the year.

Hopefully, the review is better than karma at judging enduring value. If we have accurate prediction markets on the review results, maybe we can have better incentives on LessWrong today. Will this post make the top fifty?

Parents think it’s not okay to roll a toy down the slide, seriously?

Generally they’re opposed to using toys not as intended. It is kinda dicey given they can’t easily see if anyone is at the bottom of the slide, but the worst that happens is someone gets knocked over.

There are other things on with playgrounds I think. Here (NZ), there has been a big movement toward making playgrounds safer—which has made them a great deal less fun. Since children still want adventure and a challenge, they use playgrounds in ways not intended (eg on top of frames holding swings etc).

Apparently our kids were “feral”. As far as I can tell, this was for being allowed in the bush unsupervised. They got by on one broken leg, 4 pulled elbows, one concussion plus usual scrapes and bruises which help teach limits. All but the concussion (on a school playground during break) happened while supervised. Maybe we werent paying enough attention.

But my own upbringing had far more freedom. Only 1km to beach and the rule was no going into water without an adult, no digging in sand dunes, and “careful on the road” walking to and fro. Oh and tell an adult where you were going. The environment did not seem as safe to us when our own children came along. Perception? Reality? Lot more cars for one thing.

Oh, and lets hear it for the scout movement. Getting really dirty, proper physical challenges. My son did sea scouts where supervision amounted mostly to ensuring they were wearing life jackets and fishing them out of water if required. They raced in, rigged their boats and got onto water as fast as possible with no direction at all. Water fights, boardings, and races all ensued. On the way, some pretty good water/boat skills developed mostly by osmosis.

I think we should be discouraging unjustified appeals to authority in our children, so...

”Rehearsing with my kids what they’d say if a grownup asks why they’re alone: “

My parents said it’s ok for me to be hereThe socially optimal level of abduction/traffic accident risk is not zero”What would you expect to happen after the kid responded with “The socially optimal level of abduction/traffic accident risk is not zero”?

I expect the grown-up would probably look confused, then question the child further. The well-rehearsed child would then explain the negative externalities that society has imposed upon itself by reducing these risks to near-zero, and how it is optimal for society to only reduce these risks until the marginal benefit of further risk reduction is equal to the marginal cost.

At this point, if your child has managed to make the case effectively, the grown-up would realise that the child is probably mature enough to make their own decisions whether to stay outside alone or not.

There’s nothing unjustified about appealing to your parents’ authority. Parents are legally responsible for their children: they have literal (not epistemic) authority over them, although it’s not absolute.

Technically true, but it’s a very unagentic way for a five-year old to respond to something they should have the capability to justify through argument.

My prediction is that giving such population-level arguments in response to why they are by themselves is much less likely to result in being left alone (presumably, the goal) than by saying their parents said it’s okay, so would show lower levels of instrumental rationality, rather than demonstrate more agency.

I presume the stated goal of schooling your child in this way is to set the grown-up’s mind at ease, rather than ensuring the child is left alone (which is probably the default outcome), and I expect both responses would suffice for this instrumental purpose.