The Lost schools of Thought in Hinduism and What They Mean.

TL;DR: Hinduism, the world’s 3rd/4th largest belief system, has surprising, rational roots that go beyond idolatry and polytheism. This piece unravels the richness of its intellectual heritage and first principles thinking, dissecting various schools of thought – from the 6 classical to 4 non-traditional branches (covering monotheism, polytheism, pantheism, atheism, nihilism, and hedonism and a bunch of other isms). Also learn why these schools collapsed and the ”growth hacking” techniques that led to the idolatory and prayer to win over other schools.

Hinduism (or Sanatana Dharma if you’re feeling fancy) is a bit of a chameleon — it can take on a bunch of different shapes and sizes depending on who’s practicing it.

It’s a buffet of beliefs, with options ranging from hedonism (all about pleasure) to dharma (duty and morals over everything else), from meditation to prayer, from theism (god exists) to atheism (god doesn’t exist).

It forms a strange loop of interconnected ideas and practices, referencing one another, forming a unique world of faith that’s hard to define. But we’ll give it a shot anyway

Part I. The Truth of Truth of Hinduism

Hinduism’s got a bunch of philosophical systems and schools.

There are 6 major traditional schools with 4 major sects following ideas from these schools. And there are 4 other non-traditional schools.

The Traditional schools in Part 1 follow the Vedas and Upanishads and are called Astika. We’ll cover 6 of these below. We’ve got 6 big schools and 4 major sects (some would say cults) using ideas from these schools.

Then there are the “Non-Traditional” schools, or Nastika, including Charvakas, Ajivikas, Buddhism, and Jainism, mentioned in Part 3.

These ideas popped up (or at least got written down) around 1500-500 BCE, after the Indus Valley Civilisation went bust. But they’re probably older than that.

Heads up: Some “Hindus” think Nastika means atheism. This isn’t true. Even Astika schools can be atheistic. Nastika just means they don’t believe in Vedas to be their core texts. Some Nastika schools (Charvaka) are atheistic, while others (Buddhism, Jainism) traditionally don’t comment on the whole god thing too much.

1.1. The 6 Major Schools (And Why You Only Know One)

Hinduism’s got 6 classic systems, the “Shad Darshanas.”

They talk about metaphysics, knowledge, Truth, and ethics, but they all admire the Vedas, those ancient Hindu texts. They aim to understand reality and find a path to spiritual freedom (moksha) or self-realization.

The six systems are:

Vedanta: Founded by Sage Vyasa, this influential school focuses on the Upanishads, the deep philosophical bits of the Vedas. These texts are also called Vedanta, which means the end of the Vedas, which is what the Upanishads are. It has sub-schools like Advaita Vedanta (non-dualism), Vishista-Advaita Vedanta (qualified non-dualism), and Dvaita Vedanta (dualism). If you’re Hindu, you’re probably into Vedanta, and maybe just a slice of it.

Mimamsa: Sage Jaimini’s brainchild, it’s all about Vedic rituals and duties (karma) for worldly gains and liberation. It focuses on how rituals, sacrifices, and observances matter in deity worship and life goals (think dharma, artha, kama, and moksha).

Samkhya: Sage Kapila’s dualistic philosophy based on atheism, from around 600 BCE. It focuses on the difference between the Purusha (consciousness) from Prakriti (matter) and aims for spiritual freedom through understanding this distinction as the Ultimate Reality. No deity worship or traditional God-like human belief here (sorry Krishna).

Yoga: Sage Patanjali’s Yoga is like Samkhya’s sibling but focuses on practical methods for spiritual freedom through meditation and ethical discipline. The Yoga Sutras lay out the eightfold path (Ashtanga Yoga) for enlightenment. You might have seen it influence the West in the form of stretching exercises. If it helped some of them get enlightened quicker, why not?

Nyaya: Sage Gautama’s logical system is all about getting valid knowledge. It’s big on logical reasoning and systematically analysing reality.

Vaisheshika: Sage Kanada’s atomistic, pluralistic philosophy says the universe is made of eternal atoms (paramanus). It’s got a scientific vibe and hangs out with the Nyaya school in logic and epistemology.

1.2. Major Sects and Traditions — Or Where do Gods and Idol Worship Come From?

Traditional Hinduism has more than just the six classical philosophies we’ve talked about. There are also fun subcultures like Vaishnavism, Shaivism, Smartism, and Shaktism, where people worship gods like Vishnu, Shiva, and goddesses. These traditions are like remixes of the classical ones, with idol worship for an extra personal connection.

Vaishnavism (worship of Vishnu): Vaishnavism is all about Vishnu and his cool alter egos (avatars) like Rama and Krishna. Vaishnavites believe that Vishnu is the supreme reality and that devotion (bhakti) to Vishnu is the path to spiritual liberation (moksha).

Shaivism (worship of Shiva): Shiva’s the main man here. In Shaivism, various paths can lead to spiritual liberation, including devotion (bhakti), meditation, and the practice of yoga.

Smartism (worship of multiple deities): This is for those who can’t pick a favourite god, so they worship multiple deities. Smartism is often associated with Advaita Vedanta, as it emphasises the non-dual nature of reality and the unity of the self (Atman) and Brahman.

Shaktism (worship of goddesses): Shaktism is for goddess fans, celebrating girl power through divine feminine energy (like Durga, Kali, Saraswati, Laxmi).

All of these are influenced by and take inspiration from different parts of the 6 schools of Hinduism. Eg: The eightfold path of Yoga (Ashtanga Yoga) can be adapted to suit the specific goals and beliefs of Vaishnavism, Shaivism, Smartism, and Shaktism, promoting physical, mental, and spiritual well-being.

You might wonder if these “Gods” were real people or inspired by them. The answer is a bit of both.

Gods often were given human-like qualities and forms to make them more relatable and accessible, helping folks connect personally with their chosen deity.

Brahma, in many ways, is another word for the Universe. Brahma’s creation represents the universe’s birth. This abstract idea likely led to human-like characters and stories to make it more understandable to people.

Some, like Krishna, were real people that were so enlightened that they earned deity status. Others, like Shiva, might have been inspired by ultra-wise yogis (maybe the “Adiyogi” or one of the first Yogis) who had insights about ultimate reality.

Hinduism has a thing for turning enlightened folks into gods – just check out those TV gurus!

Part II. How Deity Worship Grew

Now why did this Vedanta take over the other schools in popularity? For this to make sense, we need to understand the Bhakti Movement, Growth Hacking of atomic networks to understand this better, and a guy named Adi Shankaracharya.

2.1. The Bhakti Movement and the Birth of “Modern Hinduism” via Growth Hacking

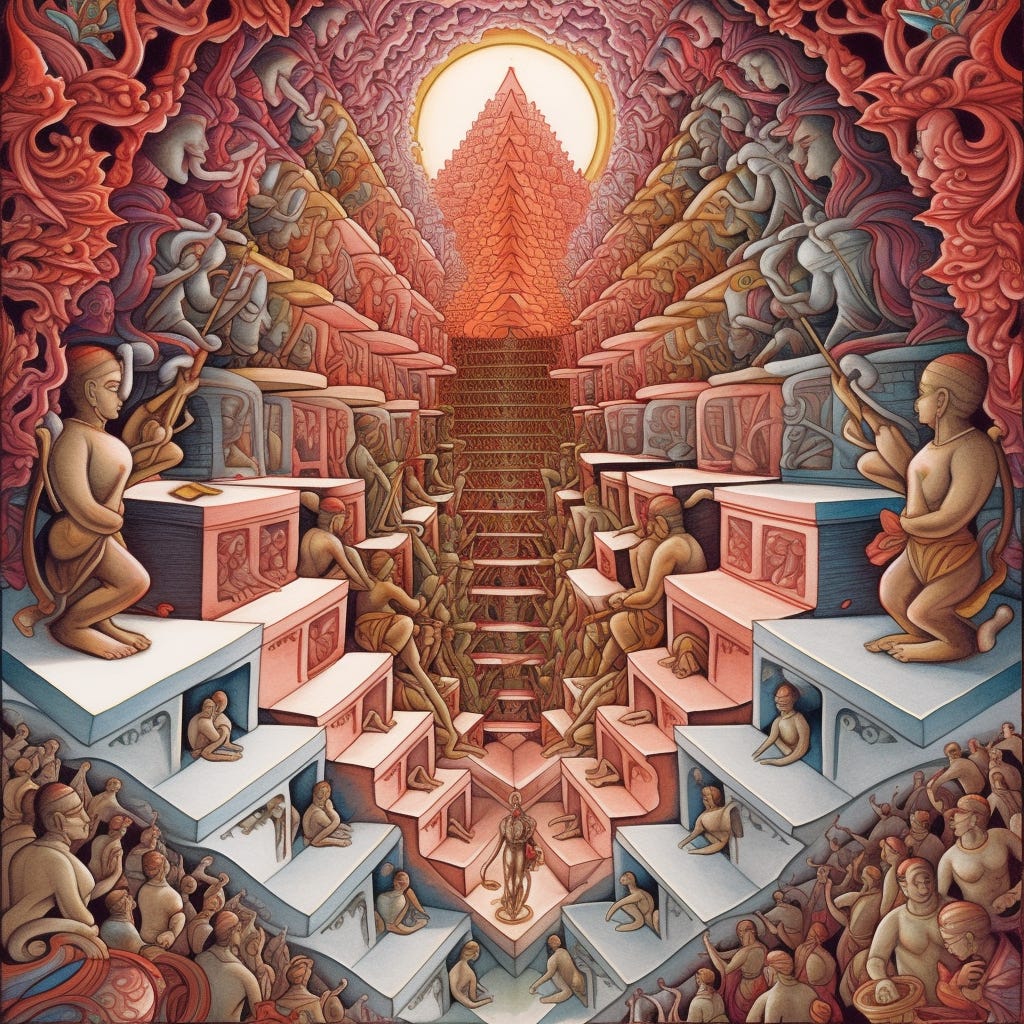

The Bhakti Movement and one of the first viral loops, midjourney

The Bhakti Movement, lasting from the 7th to 17th centuries, aimed to create a personal, emotional connection to the divine through devotion (bhakti) and the practice of singing hymns, prayers, and poetry.

It was highly successful in spreading its message and gaining followers. It used “growth hacking” techniques, such as:

Inclusivity: Open to everyone, regardless of caste or status, it broke down social barriers.

Vernacular languages: Using regional languages instead of Sanskrit made teachings more accessible.

Emotional appeal: Focusing on heartfelt relationships with God resonated with many people, through devotion and love.

Iconic leaders: Charismatic figures like Kabir, Meera Bai, and Tulsidas inspired followers.

Integration of local traditions and customs: Adapting to local traditions, myths, and legends into its teachings, made it easier for people to relate to and accept the ideas being presented. Leveraging a kind of familiarity bias.

Simplicity of practice: Singing and chanting made it easy to adopt. It did not require extensive knowledge of scriptures or rituals.

Community-building: It fostered a sense of belonging attracted more followers, who would gather to sing, pray, and share their experiences. This sense of belonging and shared purpose helped to strengthen the movement and attract new adherents.

2.2. What’s with this Adi Shankaracharya guy?

Adi Shankaracharya, the 8th-century philosopher and founder of the Advaita Vedanta school, played a significant role in reviving and reforming Hinduism. He knew not everyone could grasp his Advaita Vedanta philosophy right away, so he saw the value in devotional practices (Bhakti) as stepping stones to self-realization.

Picture him saying, “You might not be ready for this all deep abstract stuff yet, so keep worshiping those deities to build your focus and devotion.”

He understood that for many people, worshiping deities can serve as an essential means to cultivate devotion, discipline, and focus, which can ultimately lead them towards the path of self-realization.

Shankaracharya set up four monastic centres in India, each dedicated to a different deity, to teach his philosophy and preserve knowledge. He also revitalised temples and pilgrimage sites to encourage spiritual growth.

His approach was practical, simple and accessible for most. Like a good Math teacher, he tried to make sure no one slacks, knowing well the ultimate truth and understanding will only be attained by those who really try.

2.3. How Hinduism Competes — “If you can’t beat ‘em, join ’em”

Hinduism has a knack for adapting and bouncing back, growing and staying strong despite new religions and belief systems. Its strategy is like “if you can’t beat ‘em, join ’em.”

Two examples:

Buddhism: Born in India around the 5th century BCE, Buddhism, based on the teachings of Siddhartha Gautama, challenged Hindu practices like rituals and the caste system. Hinduism fought back with love by absorbing some Buddhist ideas and even considering Buddha as an avatar of the Hindu god Vishnu. Thanks to our dear friend Adi Shankaracharya, Hinduism made a comeback, and Buddhism’s influence in India faded.

Jainism: Jainism emerged around the 6th century BCE, advocating nonviolence, asceticism, and strict ethics. Hinduism and Jainism found a way to coexist, with Hinduism adopting some Jain ideas like ahimsa (nonviolence) and even revering some Jain figures, such as Mahavira.

III. Beyond the Vedas—More Atheism and the Lost Contrarians

Charvaka, Jains, Buddhists, and Tribal Religions are like the “Fab Four” of non-traditional belief systems within Hinduism. Some Hindus might not even consider this as part of Hinduism (hence non-traditional).

They remind us that Indian philosophy loves to mix things up and keep it interesting. We have already talked about Jainism and Buddhism in the competition part above. More on the other two:

Charvaka (hedonists): This quirky cousin of Hindu philosophy, doesn’t fit in with the six classical systems. It’s like the rebel at the family reunion, questioning everything and challenging traditions.

It fundamentally rejects the authority of the Vedas and the concept of an afterlife.

While other Hindu philosophies seek spiritual liberation, Charvaka says, “Let’s party!” It’s all about pleasure and enjoying the material world (or hedonism as Greeks would call it).

Ajivikas (kinda like Indian nihilism with morals and a lot of self-discipline): This is a long-lost Indian philosophy club from 6th century BCE. Their founder, Makkhali Gosala, hung out with big names like Mahavira and Buddha. They believed everything is predestined, so don’t bother trying to change anything. Quite the opposite of Jainism and Buddhism really, which were all about personal responsibility.

These guys loved extreme asceticism and nonviolence. They’d fast, meditate, and say no to worldly pleasures. Some even stood in awkward positions for ages or walked around naked to show how little they cared about stuff.

Ajivikas were quite the trend during the Mauryan Empire, but eventually, they lost their mojo.

Buddhism, Jainism, and a revived Hinduism stole the limelight, leaving Ajivikas and Charvakas forgotten. Now, only a few ancient texts and inscriptions remain as a memory of their once-thriving philosophy.

4. The Lost Culture of Debate and First Principles

4.1. The Lost Art of Open Debate and Disagreement

Hinduism’s culture of debate (Shastrarth) wasn’t just for the classical systems. Hindu scholars also debated with heterodox schools like Buddhism, Jainism, and Charvaka, which questioned traditional Hindu ideas and practices. These dialogues sharpened everyone’s intellectual skills, making ancient India a hotbed of vibrant and dynamic thinking.

It’s tough to find modern examples of these debates. They used to happen in Sanskrit, giving them a sophisticated touch. They were well-documented, and the knowledge gained was called vada-vidya (literally: argument knowledge).

Here is something close to it:

4.2. Vedic Thinking is the original First Principles Thinking.

The culture of first principles and debate is evident in Hindu texts like the Upanishads, which feature dialogues between teachers and students delving into deep metaphysical questions. The Bhagavad Gita, a key Hindu text, presents a conversation between Prince Arjuna and the god Krishna, discussing reality, duty, and the path to self-realization.

The Vedas recommend using the “neti neti” method, meaning “not this, not that.” It’s like playing a game of 20 questions, where you try to guess the answer by the process of elimination. Vedas wanted you to guess the answer of ultimate truth or reality by rejecting everything that is not it.

The Vedas have always been about questioning assumptions and beliefs, arriving at one’s own conclusions based on evidence and reasoning. But nowadays, it seems like modern Hindus are just ticking off boxes, praying for 5 minutes, skipping non-veg on one day a week, and reading a small book about it. It’s more bookish knowledge than experiential knowledge, which goes against the very purpose that Shankaracharya had in mind. Maybe he knew this would happen. Hey, maybe it still helps. Let me know if it does.

5. Appendix

5.1. The Vedas

The Vedas are the OG texts of Hinduism, considered the most sacred and ancient. They were supposedly revealed to ancient sages by the gods and passed down through the generations. There are four Vedas: Rigveda, Samaveda, Yajurveda, and Atharvaveda.

Rigveda: The oldest and most important of the Vedas, it consists of 1,028 hymns (suktas) dedicated to various deities, including Soma (a sacred ritual drink which some think was magic mushrooms).

Samaveda: It’s a collection of Rigveda and other verses to be sung during rituals.

Yajurveda: It has formulas for rituals and sacrifices. Providing lots of administrative details around it.

Atharvaveda: This has hymns, incantations, and spells for healing, protection, and other purposes.

5.2. Upanishads

The Upanishads are the later part of the Vedas and are considered the philosophical and spiritual core of Hinduism. The term “Upanishad” (उपनिषद्) is often translated as “sitting down near” or “sitting close to.” This term reflects the traditional method of receiving spiritual teachings in ancient India, where students would sit near their teacher (guru) to learn the sacred knowledge and wisdom.

Isha Upanishad emphasises renunciation and detachment from the material world, while the

Kena Upanishad explores the divine knowledge and relationship between the individual and the divine.

Katha Upanishad has a conversation between a young seeker and the god of death.

Prashna Upanishad has a series of Q&As between a sage and his students.

Mundaka Upanishad emphasises spiritual knowledge and meditation.

Mandukya Upanishad delves into consciousness through the sacred syllable “Om.”

Taittiriya Upanishad focuses on the path to self-realization.

Aitareya Upanishad explores the creation of the universe.

Chandogya Upanishad has dialogues on the nature of the self, Brahman, and the universe.

Brihadaranyaka Upanishad is one of the oldest and largest, discussing the ultimate purpose of human existence.

Shvetashvatara Upanishad takes a theistic approach, discussing the attributes of God and the role of devotion in spiritual liberation.

Kaushitaki Upanishad explores the nature of the self, death, and the afterlife

Maitri Upanishad discusses the relationship between the self, the mind, and the senses.

6. References & Footnotes

Hinduism is sometimes called “a way of life” instead of a religion. Sanatana Dharma is a more traditional term for it. The term “Hinduism” came from the Persian word “Hindu” which referred to people living beyond the river Sindhu (Indus), and was adopted by India’s colonial powers, . Sanatana Dharma represents timeless and universal principles that govern the cosmos, human life, and morality. It’s the eternal essence of Hindu teachings, beliefs, practices, and philosophical systems.

Advaita Vedanta is idea that ultimate reality is Brahman/universe, which is identical to the individual self/Atman

Is there TL;DR? What would someone who frequents this site want to know about the topic? In one paragraph.

The most interesting takeaway for LessWrong might be the Vedic First-Principles Thinking Ideas like “neti neti” (read 4.2)

I wanted to cover more than this for people curious to understand the 3rd or 4th most followed religion better because it is barely ever discussed :)

Added a TL;DR. Thanks.

I see what you did there!

This is nice, but all this information is available on Wikipedia, and you never actually bothered to explain why rationalists ought to care about Hinduism in the first place. I happen to be very fond of Kashmiri Shaivism, due to my own spiritual experiences mysteriously having led me to nearly replicate its theology (though with different names, symbols, etc of course, since I’m a white American!) as a teen. Maybe someday I’ll have the courage to write a post on here about how I manage to be a rationalist and a gnostic theist at the same time. But it’s unlikely to appeal to most readers.

Dang, it’s nice to find another ‘Kashmir’ Shaiva here, of all places!

Do you practice? (I mean this in the sense of practicing the inner yogas/meditation, not in the sense of joining a religion.)

(I found this post when searching for the word ‘dharma’ on LW, to see what the word means for the community. I actually think this post is def instructive, but still written from within a reductive lens that privileges the Astika schools rather than now.)

Well, as I attempted to express in the original comment, I am not a Shaiva, but rather I had mystical experiences and things as a teen that led me to invent my own religion from scratch which has similarities with various other belief systems, and Kashmir Shaivism is one of them. For the most part however it’s just a kind of background element of my existence, part of my ontology, and not something I put much attention towards actively anymore. In practice I’m effectively an atheist physicalist like everyone else here. It’s just… there’s also something that lurks beneath. Or there used to be. I’ve gotten more disillusioned, more empty-souled and this-worldly as I’ve gotten older, and I don’t really know how to get back the way I used to feel. Probably psychedelics is the only way; meditation doesn’t do anything for me.

Added a TL;DR to explain that. And please do write that article. Would love to hear the rationalisation :)

That was interesting to read, but what makes this a rationalist guide?

I’d love to see an English transcript of that video!

I own a few scholarly texts from india about temple architecture. Despite their best efforts, the authors can’t help themselves but describe mythology (surrounding temples, religion etc) as if it were history.

Hinduism is also very amorphous and culture and regional norms greatly overlaps with what constitutes the actual religious system—and this makes secular taxonomy very hard. At least it makes it inaccessible.

What I find “rationalist” about this essay is that it attempts to offer a secular taxonomy, and attempts to overcome very common mistakes (like conflating mythology with history).

Thanks. Never seen all this before in one place. Samkhya sounds interesting.

Really great and articulate post! Thanks for sharing!

I think you forgot to discuss this non-traditional belief system.