Initiation Ceremony

The torches that lit the narrow stairwell burned intensely and in the wrong color, flame like melting gold or shattered suns.

192… 193...

Brennan’s sandals clicked softly on the stone steps, snicking in sequence, like dominos very slowly falling.

227… 228...

Half a circle ahead of him, a trailing fringe of dark cloth whispered down the stairs, the robed figure itself staying just out of sight.

239… 240...

Not much longer, Brennan predicted to himself, and his guess was accurate:

Sixteen times sixteen steps was the number, and they stood before the portal of glass.

The great curved gate had been wrought with cunning, humor, and close attention to indices of refraction: it warped light, bent it, folded it, and generally abused it, so that there were hints of what was on the other side (stronger light sources, dark walls) but no possible way of seeing through—unless, of course, you had the key: the counter-door, thick for thin and thin for thick, in which case the two would cancel out.

From the robed figure beside Brennan, two hands emerged, gloved in reflective cloth to conceal skin’s color. Fingers like slim mirrors grasped the handles of the warped gate—handles that Brennan had not guessed; in all that distortion, shapes could only be anticipated, not seen.

“Do you want to know?” whispered the guide; a whisper nearly as loud as an ordinary voice, but not revealing the slightest hint of gender.

Brennan paused. The answer to the question seemed suspiciously, indeed extraordinarily obvious, even for ritual.

“Yes,” Brennan said finally.

The guide only regarded him silently.

“Yes, I want to know,” said Brennan.

“Know what, exactly?” whispered the figure.

Brennan’s face scrunched up in concentration, trying to visualize the game to its end, and hoping he hadn’t blown it already; until finally he fell back on the first and last resort, which is the truth:

“It doesn’t matter,” said Brennan, “the answer is still yes.”

The glass gate parted down the middle, and slid, with only the tiniest scraping sound, into the surrounding stone.

The revealed room was lined, wall-to-wall, with figures robed and hooded in light-absorbing cloth. The straight walls were not themselves black stone, but mirrored, tiling a square grid of dark robes out to infinity in all directions; so that it seemed as if the people of some much vaster city, or perhaps the whole human kind, watched in assembly. There was a hint of moist warmth in the air of the room, the breath of the gathered: a scent of crowds.

Brennan’s guide moved to the center of the square, where burned four torches of that relentless yellow flame. Brennan followed, and when he stopped, he realized with a slight shock that all the cowled hoods were now looking directly at him. Brennan had never before in his life been the focus of such absolute attention; it was frightening, but not entirely unpleasant.

“He is here,” said the guide in that strange loud whisper.

The endless grid of robed figures replied in one voice: perfectly blended, exactly synchronized, so that not a single individual could be singled out from the rest, and betrayed:

“Who is absent?”

“Jakob Bernoulli,” intoned the guide, and the walls replied:

“Is dead but not forgotten.”

Abraham de Moivre,”

“Is dead but not forgotten.”

“Pierre-Simon Laplace,”

“Is dead but not forgotten.”

“Edwin Thompson Jaynes,”

“Is dead but not forgotten.”

“They died,” said the guide, “and they are lost to us; but we still have each other, and the project continues.”

In the silence, the guide turned to Brennan, and stretched forth a hand, on which rested a small ring of nearly transparent material.

Brennan stepped forward to take the ring—

But the hand clenched tightly shut.

“If three-fourths of the humans in this room are women,” said the guide, “and three-fourths of the women and half of the men belong to the Heresy of Virtue, and I am a Virtuist, what is the probability that I am a man?”

“Two-elevenths,” Brennan said confidently.

There was a moment of absolute silence.

Then a titter of shocked laughter.

The guide’s whisper came again, truly quiet this time, almost nonexistent: “It’s one-sixth, actually.”

Brennan’s cheeks were flaming so hard that he thought his face might melt off. The instinct was very strong to run out of the room and up the stairs and flee the city and change his name and start his life over again and get it right this time.

“An honest mistake is at least honest,” said the guide, louder now, “and we may know the honesty by its relinquishment. If I am a Virtuist, what is the probability that I am a man?”

“One—” Brennan started to say.

Then he stopped. Again, the horrible silence.

“Just say ‘one-sixth’ already,” stage-whispered the figure, this time loud enough for the walls to hear; then there was more laughter, not all of it kind.

Brennan was breathing rapidly and there was sweat on his forehead. If he was wrong about this, he really was going to flee the city. “Three fourths women times three fourths Virtuists is nine sixteenths female Virtuists in this room. One fourth men times one half Virtuists is two sixteenths male Virtuists. If I have only that information and the fact that you are a Virtuist, I would then estimate odds of two to nine, or a probability of two-elevenths, that you are male. Though I do not, in fact, believe the information given is correct. For one thing, it seems too neat. For another, there are an odd number of people in this room.”

The hand stretched out again, and opened.

Brennan took the ring. It looked almost invisible, in the torchlight; not glass, but some material with a refractive index very close to air. The ring was warm from the guide’s hand, and felt like a tiny living thing as it embraced his finger.

The relief was so great that he nearly didn’t hear the cowled figures applauding.

From the robed guide came one last whisper:

“You are now a novice of the Bayesian Conspiracy.”

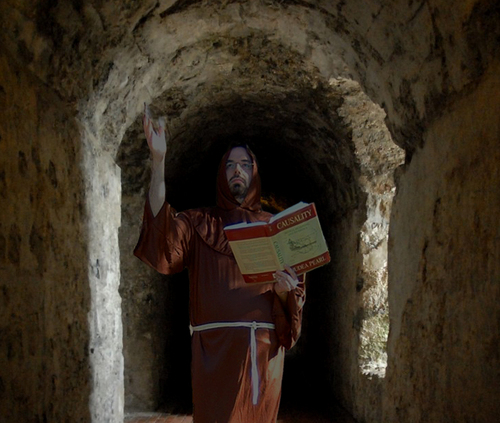

Image: The Bayesian Master, by Erin Devereux

- That Alien Message by (22 May 2008 5:55 UTC; 399 points)

- The Ultimate Source by (15 Jun 2008 9:01 UTC; 79 points)

- The Quantum Physics Sequence by (11 Jun 2008 3:42 UTC; 74 points)

- 's comment on Open thread, March 17-31, 2013 by (17 Mar 2013 18:46 UTC; 42 points)

- Awww, a Zebra by (1 Oct 2008 1:28 UTC; 31 points)

- 's comment on RIP Doug Engelbart by (4 Jul 2013 3:18 UTC; 16 points)

- 's comment on Should LW have a public censorship policy? by (12 Dec 2010 20:20 UTC; 15 points)

- 's comment on Lesswrong UK planning thread by (24 Jan 2010 9:53 UTC; 12 points)

- Rationality Reading Group: Part Q: Joy in the Merely Real by (30 Dec 2015 23:16 UTC; 9 points)

- 's comment on The elephant in the room, AMA by (13 May 2011 0:09 UTC; 6 points)

- 's comment on Extreme Rationality: It’s Not That Great by (5 Dec 2010 20:58 UTC; 6 points)

- [SEQ RERUN] Initiation Ceremony by (18 Mar 2012 4:49 UTC; 6 points)

- 's comment on Things You Can’t Countersignal by (19 Feb 2010 2:56 UTC; 4 points)

- 's comment on Class Project by (20 May 2020 0:33 UTC; 4 points)

- 's comment on 3 Levels of Rationality Verification by (13 Sep 2011 19:52 UTC; 3 points)

- 's comment on Query the LessWrong Hivemind by (8 Nov 2011 16:25 UTC; 3 points)

- 's comment on What can we learn from freemasonry? by (25 Nov 2013 23:00 UTC; 2 points)

- 's comment on Open thread, 30 June 2014- 6 July 2014 by (2 Jul 2014 10:09 UTC; 2 points)

- 's comment on Welcome to Less Wrong! (2012) by (12 May 2012 23:26 UTC; 2 points)

- 's comment on [SEQ RERUN] Failing to Learn from History by (9 Aug 2011 18:42 UTC; 2 points)

- 's comment on Harry Potter and the Methods of Rationality discussion thread, part 15, chapter 84 by (12 Apr 2012 15:42 UTC; 2 points)

- 's comment on Misleading the witness by (9 Aug 2009 21:28 UTC; 2 points)

- 's comment on Beware of Other-Optimizing by (7 Aug 2011 13:31 UTC; 1 point)

- 's comment on Open thread, Mar. 16 - Mar. 22, 2015 by (17 Mar 2015 14:05 UTC; 1 point)

- 's comment on Welcome to Less Wrong! (2010-2011) by (28 Aug 2011 6:26 UTC; 1 point)

- 's comment on Welcome to Less Wrong! (2010-2011) by (17 Dec 2010 20:06 UTC; 0 points)

- 's comment on The Martial Art of Rationality by (13 Aug 2011 1:06 UTC; -4 points)

No comments? Either you’re all stunned speechless, or you’ve simply gotten used to me by now.

Shame that I often feel like that poor fool Brennan, I should have payed more attention during my math classes but they sure as hell didn’t make it easy. I like how you named the protagonist Brennan “Living by the Beacon” aka. living by the beacon of Bayes? Makes me think wheather or not the other names you invented in your stories mean something, too.

That is similar to the kind of thrill, the feelings I’d undergo when reading fantasy or science fiction, but then for other mysteries, other secrets. I can now see how you could put science and technical knowledge in their place.

I’d been under the impression that the mysteries hinted at in fiction are always easier and more intuitive to grasp, and require less personal work per amount of result, than science does, however.

I don’t know if that means I’d maybe grow tired sooner and give up on science, frustrated by the sluggish pace of my progress compared to the efforts I put into my learning, or if the difficulty of learning the innumerable details of science would make it all the more worthwile, and would make the fun last much longer than it would for, say, fantasy magic learning.

Probably both.

Well… there’s not much to say, here. It was an amusing piece of fiction, but doesn’t seem to be more than that. If I were asked that question, I’d ask for some pencil and paper because I’m mediocre at mental arithmetic. (My algorithm for solving that kind of problem involves drawing lines on paper to find the right equation to plug numbers into.)

I write them out as frequencies instead of probabilities; it makes it much easier to conceptualize, a fact which is well documented but poorly understood.

I would guess thinking “frequency” implies it happens, while “probability” might trigger the But there is still a chance, right ? rationalization.

Ha, I’m still reduced to drawing little stars on a piece of paper and circling them into different groups.

Man I need to work on this thing.

Maybe this is a dumb question, but where did 1⁄6 come from? I mean, when they asked the question I did the math and came up with 2⁄11, and I don’t even see how you might get 1⁄6.

The point is that they are giving a wrong answer to confuse you, to see if you really believe in Bayes’s Theorem or if instead you will just capitulate to the word of an authority.

9/16ths of the people present are female Virtuists, and 2/16ths are male Virtuists. If you correctly calculate that 2/(9+2) of Virtuists are male, but mistakenly add 9 and 2 to get 12, you’d get one-sixth as your final answer. There might be other equivalent mistakes, but that seems the most likely to lead to the answer given.

Of course, it’s irrelevant what the actual mistake was since the idea was to see if you’ll let your biases sway you from the correct answer.

“If I were asked that question, I’d ask for some pencil and paper because I’m mediocre at mental arithmetic.”

I probably would have gotten the answer, but it wouldn’t have occurred to me to say that the initial information was wrong. It’s part of an initiation ritual for a mathematical cult; why would anyone bother checking to see if the actual numbers are correct? Saying “I do not, in fact, believe the information given is correct” feels like saying “The air around me contains oxygen”.

EY uses Bayes to frame reality ever closer, not just to answer abstract homework on paper and call it a day.

If you solve a given problem without spotting it is ill-formed, your answer is correct but not practical.

I thought of the possibility that Brennan might be counted as one of the people in the room (and thus he has more information than was stated) as a possible reason the one-sixth answer could be correct. From that angle, whether the information given describes the current moment is a very relevant concern.

After doing the math, it works out that if there are exactly 80 people in the room, and Brennar himself belongs to the Heresy of Virtue (highly unlikely), then one-sixth is in fact the correct estimation (based on 45 female virtuists, and 9 male virtuists other than Brennar).

If you don’t care what you know, as long as you know it, you’d be better off studying theology. I have some crystals and tarot cards you’ll probably want to purchase, too.

That isn’t “knowing” something. That’s believing it.

Not necessarily. I know a large amount of halachah (Orthodox Jewish law). I don’t believe any of it. I also know a smaller amount of Catholic theology. I don’t believe any of that either. Prioritization still makes sense. These really aren’t great things to know much about if one wants any sort of real understanding.

You know the fact “the content of the halachah is _” (I don’t know what the halachah says). However, you do not know “the content of the halachah is true”, because that is a falsehood. If it were costless, I would choose to know the former, but not the latter.

But you CAN’T know the latter, not on the standard theory of knowledge as “justified true belief”. You’d have belief, but probably not justified and surely not true.

That hasn’t been ‘standard’ since Gettier, I think.

Sadly, people have been trying to prop up that rotting corpse ever since. Goldman is a decent example.

Great creative effort, in thinking about useful solutions to a tough problem (getting people to better value our best developed forms of rational decision-making).

Dave Orr, the rite of passage is to give the correct answer, 2⁄11, in the face of pressure to conform.

Nice picture.

I don’t know if a verbal examination like this is suitable of a scientific conspiracy, though. Keep the mysticism and ritual, but give the initiates the chance to return their answers in writing, to make it more fair and reduce the stress factor.

Stepping inside the Great Library, Brennan breathed in surprise as he let his gaze wander around the hall. All these books! Shelves after shelves of writing—and when he saw the names on them, he could feel his heart skip a beat. Darwin, Tooby & Cosmides, Kahneman & Tversky… this was the sacred hall of the true grand masters, the depository of all their wisdom!

Hearing a sound, Brennan lowered his gaze, noticing the robed figure that had appeared in front of him. Remembering his manners, he bowed deep. “Respected master, I am novice Brennan of the Bayesian Conspiracy, here to scour the depths of my mind for answers to the questions you pose. I am at your service.”

“Oook.”

Following the robed figure, Brennan was led to a table and a chair. He sat down, and patiently waited as he was brought the Implements of Testing: the Pencil of Masters, the Notebook of Understanding, and the Eraser of Mistakes Undone. Finally, he was brought The Envelope, marked with the seal of the Conspiracy, personally sealed by the Council of Twelve.

And so it begins… he thought as he drew one more breath, then broke the seal and pulled out the contents to see what challenges he would be met with this time.

I really like “The Eraser of Mistakes Undone” for some reason.

We should name all our mundane magic this way. “The Car of Traveling” “The Airplane of Flying Metal” “The Laptop of Encapsulated Thought”

It’s very Napoleon of Notting Hill, isn’t it?

Upvoted for the presence of the Librarian.

(And I just realized that I misread half of the story. Yes, for this particular scenario a verbal examination makes more sense than a written one. Ah well. goes to hunt for a new brain)

I don’t know if a verbal examination like this is suitable of a scientific conspiracy, though. Keep the mysticism and ritual, but give the initiates the chance to return their answers in writing, to make it more fair and reduce the stress factor.

You may have already realized this, but what you do when you’re under stress, in life, does count.

Of course this is true, as far as it goes.

But I’m inferring something from it in context that you perhaps don’t mean, and I’d like to clarify. (Assuming you even read comments from this far back.)

Specific example: a couple of months after you posted this, I suffered a brain aneurysm that significantly impaired my working memory, to the point where even elementary logic problems—the sort that currently would barely register as problems that needed solving in the first place—required me to laboriously work them out with paper and pen. (Well, marker… my fine motor control was shot, also.)

The question arises: could I have passed this initiation ceremony?

I certainly could not have given the right answer. It would have been a challenge to repeat the problem, let alone solve it, in a verbal examination. My reply would in fact have been “I’m not sure. May I have a pen and paper?”

If the guide replies more or less as you do here, then I fail.

I draw attention to two possibilities in that scenario:

(A) This is a legitimate test of rationality, and I failed it. I simply was less rational while brain-damaged, even though it didn’t seem that way to me. That sort of thing does happen, after all.

(B) This test is confounding rationality with the ability to do mental arithmetic reliably. I was no less rational then than I am now.

If A is true, then you and the guide would be correct to exclude me from the club, and all is as it should be.

But if B is true, doing so would be an error. Not because it wasn’t fair, or wasn’t my fault, or anything like that, but because you’d be trying to build a group of rationalists while in fact excluding rationalists based on an irrelevant criterion.

Now, perhaps the error is negligible. Maybe the Bayesian Conspiracy will collect enough of the most rational minds of each generation that it’s not worth giving up the benefits of in-group formation to attract the remainder.

OTOH, maybe not… in which case the Bayesian Conspiracy is on the wrong track.

They aren’t trying to build a group of rationalists. They are trying to build a group of people who can achieve certain goals.

(nods) Fair enough. Not knowing the goals, I’m in no position to judge this fictional selection procedure… I’d have to read more stories set in this world to be entitled to an opinion there.

Trivially, if what they want is a group that is good at mental arithmetic and resisting social pressure, they’re going about it in a reasonable way.

More broadly, if they aren’t claiming that their initiation procedure preferentially selects rationalists, then my concern becomes irrelevant.

Nobody else seems to have added this response, so I will. We don’t know that this moment, in the ritual room, is the only test they undergo. Perhaps one’s ability to take a written exam is part of the public procedures. Perhaps a great open exam where anyone who wants to can sit it, running near continuously, is the first stage, and Brennan has had months in a cloisterlike environment in the public secret face of the conspiracy where the people who can study sciences but not generate new true science study?

I assume that there are other tests involved, both before and after, but I don’t see the relevance of that. I may be missing your point.

Perhaps I missed yours? Rationality requires the ability to challenge social pressure, certainly. Are you questioning whether this procedure picks rationalists from nonrationalists? If so, and on its own, I don’t argue that it would, just that it would probably be one member of a larger set of tests.

Thinking about it more now… yes, I was implicitly assuming that failing any of the tests barred further progress, and you’re right that this wasn’t actually said. I stand corrected; thanks for pointing that out.

Do we know that saying “I don’t know” is a failure? Clearly accepting the one-sixth answer given by the guide would be a failure, and stubbornly sticking to a different wrong answer is probably a failure as well, but saying “I need more time and equipment to figure this out” might very well be tolerated.

Well, right, that’s essentially the question I was asking the author of the piece.

This comment sure does seem to suggest that no, requesting more time and equipment is a failure… but no, I don’t know one way or the other, which is why I asked.

A lot of people need some specialized scientific knowledge to do their jobs. They may not be interested in the rest of it, but they are interested in that because it matters to what they’re doing. If we hide science behind a general scientific conspiracy, people like that won’t join, and they won’t be able to do their jobs effectively, and society will be poorer as a result.

How does he know there are an odd number of people in the room?

How does he know there are an odd number of people in the room?

He… um… er… counted them?

(Just like he counted the stairs, note.)

If he counted them, then he could have given a better calculation than “2/11”, since he had one additional prior that was unstated: the probability that he himself was (or was not) a male virtuist. In the same scenario, the best candidate would ask what the virtuist heresy was first, and then give an answer based on that additional information. (If the interrogator refused to answer, the answer might still be 2⁄11.)

Or, perhaps, the “if” rightly implied a hypothetical scenario, and the contents of the room as he perceived them were entirely irrelevant.

He might not know what a Virtuist is—it may be an arbitrary label for the purpose of this test, in which case the answer would not change.

Or it could already have been included in the calculation. If perhaps there had been 47 people in the room including 6 male virtuists and 5 male non-virtuists, and then Brennan arrives, a male non-virtuist, he makes all the numbers work out with 48 people and 33 virtuists of whom 6 are male (2/11).

But in fact we know it wasn’t, because there are an odd number of people in the room!

I had guessed something like that was the reason why the answer was supposed to be 1⁄6.

Funny.

Kaj Sotala:

Your story is written decently, but it sounds like a parody of pretty much any traditional exam. If you remove the write-in answers requirement, you can have much more colorful examination scenarios.

Eliezer:

This seems like a cool motivation tactic. At the same time, I’m a little afraid that thinking my knowledge makes me special and unique will cause me to be arrogant.

Any commited autodidacts want to share how their autodidactism makes them feel compared to traditional schooled learners? I’m beginning to suspect that maybe it takes a certain element of belief in the superiority of one’s methods to make autodidactism work. Otherwise you’d be running on pure curiosity, and in my experience that doesn’t always hold out for long, especially when you’re trying to tackle something more advanced.

Actually, I have been running on pure curiosity, which is great for finding out about lots and lots of things, but now I’m having trouble focussing like I want. Thirty years of following my curiosity has developed some bad habits I need to break.

For extra credit, explain how “one-tenth” could also have been the correct answer.

In my experience, the problem with running on curiousity is that, to be effective at something, one has to not take the time to investigate lots of unrelated things one is curious about.

billswift, that’s a really good point. This explains why newspapers can be bad—they arouse your curiosity, but on many different subjects, many of which are completely unproductive (such as the status of the US presidential election. For some reason, extensive coverage of voter opinion trends is within the realm of prestigious reporting.)

If you guys are going to rig elections, I want in.

Is this a maths question or a reasoning question?

What would the cult have said if the man had said something a long the lines of this to the first question.

“As probability is a subjective quality which must take all the information available to me to be valid, I’m not going to take the assumptions that were given to me. From the my estimate of your bodily proportions and the distribution of the height and weight of the general populace, and your low tone of voice compared to the average I would give you a 90% chance of being male.”

It’s an ethics question.

Brennan didn’t take the guide at his word, he re-checked his own results to see if he made a mistake. Confirming his own results, he restated them in the face of Authority telling him he was wrong, which is precisely why he was permitted into the Beyesian Conspiracy. Had he said “one-sixth”, he would undoubtedly have been denied admittance.

“to be effective at something”

This was less of a problem for me. When I am actually doing something, my curiosity tends to focus on what I’m doing. My problem now is that I am trying to study in preparation for changing my direction, and it is very hard to stick to it.

Hint for the extra credit: What is the probability that the guide is Brennan? (Zero.)

Beware the hidden prior: that all Virtuists are assumed to be either men or women.

That’s true; we did not rule out transgender Virtuists.

Not to get into too much irrelevant discussion about contemporary society’s human-labelling paradigm, I think you mean non-binary Virtuists. A lot of trans people are men or women.

Re Will Pearson’s question: something like “didn’t you hear me say ‘if’”, I should think.

All I can say is that when I scrolled down and saw the photo, my first thought was ‘awesome’.

Nice illustration of your previous post, Eliezer.

Any commited autodidacts want to share how their autodidactism makes them feel compared to traditional schooled learners? I’m beginning to suspect that maybe it takes a certain element of belief in the superiority of one’s methods to make autodidactism work

First, “traditional school learning” is itself inherently problematic. Consequently, “belief in the superiority of one’s [own] methods” is not hard to acquire.

Second, all actual learning is necessarily autodidactic anyway, because where it takes place is in your own mind, not in your interactions with others.

So yes, in order to learn, you have to be “arrogant” enough to believe that you actually can. That is, you have to have the confidence that you personally can fully appreciate the insights of “authority figures” like Issac Newton. Unfortunately, social pressures seem to discourage such “presumption” in favor of deference to authority.

“Re Will Pearson’s question: something like “didn’t you hear me say ‘if’”, I should think.”

Well they should phrase their questions better, and say what would be the probability (and probably put some caveat about that being the only information available no other prior knowledge etc), rather than what is* the probability. Imagine someone says, “If it takes 4 secs for light to move 5 metres, what is the speed of light?”. The answer should still be 3x10^8 or there abouts, the data given by someone should not always change your prediction about the world, they might be trying to trick you or exploit a bias in order for you to get things wrong. This is if it is a reasoning problem, if it is a math problem, then all the data given in the problem has to be treated as correct.

Well, I guess I’m not talking about the learning process itself so much as what keeps you going. In a traditional school environment, grades are the de facto student motivator.

My old Creative Minds professor has plenty of anti-school arguments. But when he tried attending a school without grades, he learned that it sucked: many students didn’t show up for class, and of the ones that did, the only ones who participated in classroom discussions were those who had strong opinions.

So my question is when you’re learning on your own, how do you find ways to motivate yourself? As I mentioned before, curiousity can be unreliable. Another technique is to think of what you’re doing as special and unique, and saying to yourself “Hardly anyone is teaching themselves using the direct, efficient methods that I’m using. I’m operating outside the system and learning things that very few others are learning. If I finish all the exercises in this book, I will be a Level 6 Probability Master.”

The upside of this is that you’re motivated to learn more. The downside is that it might make you arrogant.

No, Mr. Pearson. The answer includes the if-statements attached to the question—saying that c is 3x10^8 would be incorrect.

Incorrect, an interesting phrase… In what manner would the phrase, “c is approximately 3x10^8,” be incorrect. You say it is wrong, I say it is right. Who is to decide? Could I not go and measure it, and find c in the vacuum to be approximately 3x10^8?

Why is the questioner always assumed to be correct about every bit of data given? Sure I may not pass many exams taking this attitude, but the only examiner that really matters is reality, surely? We are here to learn how to reason about the world surely, not to learn to pass exams, or other random human tests.

C is only roughly 3x10^8 meters per second when traveling in a vacuum. Any interaction with matter slows it down, though usually only very slightly.

I believe the slowest light has ever been measured is 38mph (15.6 meters per second), achieved by firing a laser through sodium atoms held in a Bose-Einstein condensate (0.37 degrees Kelvin).

Pretty impressive, really.

In other words, the “if” statements are extremely important.

c is by definition the speed of light in vacuum. You use another variable (usually v) if you want the speed of light in a given refractive medium.

In a traditional school environment, grades are the de facto student motivator

Motivator of what? The point is that whatever behavior it is that grades in school serve to motivate, it is not learning per se. Indeed, grades are more often than not a motivator against learning. To quote Eliezer (emphasis added):

“[S]tudents aren’t allowed to be confused; if they started saying, ‘Wait, do I really understand this? Maybe I’d better spend a few days looking up related papers, or consult another textbook,’ they’d fail all the courses they took that quarter.” (Two More Things to Unlearn from School.)

This is where the autodidact has a distinct advantage, because he/she doesn’t have to “worry” about “failing courses”, and thus doesn’t have to actively resist this kind of pressure against learning. By contrast, if a traditional school student is interested in learning, he/she has to be willing to neglect “assigned tasks” and incur the expected social consequences. It is in this sense that I claim it is (or at least can be) easier to stay motivated outside the school system than inside.

Grades in school motivate people to gain the ability to successfully take exams, which is actually pretty well correlated to understanding the material, especially compared to, e.g., drinking until you pass out. You may be able to achieve some gains by being motivated by learning rather than by grades, but you’re way better off being motivated by grades than by nothing.

We have to accept the reality of the situation; the system is not set up to haelp people learn who desperately want to. That is actually just and good, because the fraction of the population who actually desperately want to learn is the size of a rounding error.

So, any ideas on how to become one of that incredibly tiny number of people who desparately want to learn?

Re: Will Pearson’s comment: “Well they should phrase their questions better”.

In the context of an initiation ceremony perhaps a bit of stress-inducing ambiguity may be appropriate. Anway, the hypothesis that the “if” is true appears to be refuted by the fact that there are actually an odd number of people in the room.

“One-tenth” could not have been the correct answer—not even if Brennan already belonged to the Heresy of Virtue, and this was his initiation into some other cult ;-)

It is a surprisingly attractive picture of you...

As Komponisto points out, traditional schooling is so bad at educating that belief in the superiority of one’s [own] methods is easily acquired. I first noticed traditional schooling’s ineptitude in kindergarten, and this perception was reinforced almost continuously thru the rest of my schooling.

PS: I liked the initiation ceremony fiction, Eliezer.

Tim, one-tenth would be the correct answer if Brennan were in the Heresy of Virtue, AND there were 16 people in the room. There would be 9 women in the HoV in the room, and 1 man who wasn’t Brennan; hence, one in ten.

Thanks to Mike Vassar for pointing out that, if Brennan is in the HoV, you need to count how many men are in the room.

Since there are an odd number of people in the room, the guide must be posing a hypothetical question. If Brennan is in the HoV, the correct answer would be for him to say that he needs to know how many people are in the room in the hypothetical situation.

This is a great blog post. Reading it was actually fun as I anticipated what would happen next as I do for regular fiction. I liked how the story reiterated messages you’ve talked about before but in a way that seems more clear(combined with the previous formal essays) - this is probably because storytelling has an appeal that is more accessible to most people.

At first I thought he paused after saying “one” because nothing has a probability of one or zero but that was cause I didn’t read carefully. I think something like this really would be a good motivator to learn science. Before reading your ideas on this I had a sort of unthinking distrust/dislike of overblown pomp and ritual but now that I see its possibilities as a ‘hack’ on human nature used for something worthwhile...

Funny. I found the story severely distressing to read. Got to “1/6″, halted, went, but wait, no, that can’t be right.” Actually did the calculation. Got even more confused, because I got the result the protagonist first proposed. Wondered why the fuck I can’t do math, how I am fucking up something this simple. Was painfully reminded of being terrified of being the girl who fucks up math. Still couldn’t see it. Hated my brain. Got up, got a piece of paper, wrote the calculation out on paper, stared at it. Couldn’t figure out how it could be anything but 2⁄11. Despaired, and decided to return to the story and ask in the comments where my mistake was, despite this being an ancient story and hence silly to ask and exposing me being unable to do math, which frightens me, because I couldn’t figure it out, but it felt like failing a ritual I’d be upset to fail for real. Was immensely relieved at the reveal. But I’m not sure whether I would pass this test at all. And I do think it is testing for something I want, but that it goes beyond being able to do basic math, and resist authority. I think I would have caved to self doubt. Because I remember being in a lecture, watching the prof give a proof, and thinking wait, what, this doesn’t follow, that should follow instead. Getting stuck at the line. Thinking this for 20 min of increasing distress as the prof added on more and more, trying to understand my mistake, and failing, and not noticing that the prof had meanwhile stopped writing in confusion many lines down. At which point somebody in that room of hundreds spotted it, raised his hand, and said, wait, isn’t there an error am the way up there, and pointed out the mistake I was stuck on. It was a mistake. The prof was wrong. I’d been correct. But I never even came close to raising my hand and asking about it, let alone tell him he was wrong. Not as the one girl. I couldn’t be the one girl who didn’t get this thing everyone else apparently got, I had to understand it myself, and yet couldn’t. - Super toxic mindset. Asking zero questions and admitting zero confusion is extremely detrimental to learning. But when it comes to math, I still feel strongly that admitting confusion here is a whole new category of risk. I don’t just risk revealing that I am wrong, I risk having people conclude that all women suck at this task. It adds a huge level of stress and self-doubt.

Re: Phil Goetz: There are not 16 people /currently/ in the room—since Brennan counted them. Brennan is not told in the scenario that he is in the room.

He is not told other things that might impact on the answer, such as whether there were any non-human AIs in the room who were members of the Heresy of Virtue.

“I need more information” might have been an acceptable answer—at least on the latter grounds.

“One-tenth” requires the assumption that Brennan is in the Heresy of Virtue (which is something he ought to know), the assumption that Brennan is in the room in question, and the further assumption that there are exactly 16 people there—quite a few dubious assumptions for an initiation ceremony.

Fun Fact:

Electrical Engineers have been trying to budge “Old Yellow,” the low-pressure sodium vapor lamp, from the top of the efficiency heap since the mid-1960s. They found some materials possibilities in the 1990s, but all have turned out to be too expensive.

I started reading the first chapter of Structure and Interpretation of Computer Programs and was reminded of this post.

Makes you want to learn to program, doesn’t it?

You may have already realized this, but what you do when you’re under stress, in life, does count.

indeed. And one of the things we are prone to do under stress is delude ourselves: I think that the following:

“It doesn’t matter,” said Brennan, “the answer is still yes.”

is perhaps the most important message. (Although I also like the message of not caving in to peer pressure. )

An excellent little parable, I shall keep it in mind ;-)

Come now, why doesn’t Brennan take an experimental approach: kick him or her where the balls would be, and appraise the reaction? I mean, this is a conspiracy of scientists, not Aristotelian scholastics.

Because, as my daughter learned the other day, that still hurts. Also, the person could have been a non- or pre-op transsexual woman (leaving out other variants merely for brevity).

Maybe a different experimental method...

Edit: See also: Tim_Tayler’s comment above re: hidden prior.

My understanding is that while the pain is not all that different in degree it is different in nature. I haven’t tested it but I suspect that taking a suitable sample would allow you to generate a reliable heuristic for differentiation.

Yes, different tests are likely required for determining either private self concept or publicly acknowledged identity than those that determine physical characteristics.

Caledonian: I assume he means that, for all X, if X is true, he wishes to know X. This opposed to “if the universe is made of puppies and unicorns, tell me about it, otherwise I don’t want to know.”

That was a brilliant story!

I liked the ring with n=1, nice touch. Beats wearing barbed wire round your underpants any day.

Dude. Thompson.

Oh my gosh but I actually am stunned speechless.

I can’t even begin to express the way I feel right now, Eliezer Yudkowsky, my friend, you are in possesion of a rare and powerful gift!

It only goes to show how we are all susceptible to power of stories, rather than able to examine them dispassionately, like a rationalist presumably should.

I called my math teacher over to help. We couldn’t find the answer. This isn’t promising, as I had hoped to summon him for help whenever I needed help to understand something above my highschool math education. I will make a quick request for what steps of math i should follow to have a better chance of wrapping my mind around this probability stuff, since part of my exam test seriously has ‘there are four playing cards, one is red, what is the probability of randomly picking red’ or something like that.

Regardless of such concerns; I’m pretty sure the ‘I don’t care, I just want to know’ part of it is simply curiosity, and doesn’t mean that Brennan would in any way accept silly theologies as truth, even should he be curious as to what they were teaching. I find myself plenty curious about Buddhist teachings, but in the same way I am curious about the way magic works in the TypeMoon worlds

I know this is a very old story, but I have some thoughts on it I wanted to share.

Let me first share an experience that I think everybody who has ever seriously studied math (or any complicated subject) has had. You’re working on a difficult math problem, say a complicated differential equation. You are certain your method is correct, but still your answer is wrong. You’ve checked your work, you’ve double checked it, you’ve checked it again. Your calculation seems flawless.. Finally, in desperation, you ask a friend for help. Your friend takes one glance at your work, smiles, and says: “Four times five does not equal twelve”… Oh. Yeah. Right. Good point.

We all make mistakes. Even very skilled people sometimes make elementary mistakes. Brennan in the story is doing a calculation that is very trivial for him, but it is still possible. Even if he can’t see a flaw, can’t even imagine a flaw, that doesn’t mean the odds are zero.

Yes, they are certainly very small. Brennan is saying “The odds of me making a mistake are very small, so I am confident I am correct”. But this is the Bayesian Conspiracy, not the Frequentist Conspiracy. Brennan should be asking: “Given that someone has clearly made a mistake, what are the odds of me having made it, instead of every other person in the Conspiracy. The answer is obvious.

Thus, Brennan fails as a Bayesian, and should not be accepted into the Conspiracy.

And I am not merely making a pedantic point here. This is a very important point for the real world as well. Yes, standing up to peer pressure is important, but only when it is rational. Global warning deniers also think they are standing up to peer pressure. Creationists also think they are standing up to peer pressure. And often for the exact same reason that Brennan is doing so, in this story. They thought about the issue themselves, they may even know a thing or two about it, and they really can not see any flaw in their logic, so they stick with it, convinced the odds of them having made a mistake are very small, forgetting about the huge prior.

This is actually my first post on this site. I have read quite a bit, but not everything, so I hope I am not inadvertently saying something that has been discussed before. I couldn’t find anything, and I think it’s an important point.

Welcome!

But this assumes that the Conspirator is telling him the truth, instead of testing him. I think Brennan is right in considering alternative hypotheses about the Conspirator’s motives.

There are questions of ‘epistemic hygiene’ here. If I hold a belief because someone else I trust holds that belief, I need to be careful that I don’t give other people the impression that I’m providing independent verification of that belief instead of just importing their belief. If Brennan calculated a different answer, him telling the group that will allow them to converge more quickly to the correct belief (even if he acts on the group consensus belief, because that’s the one that he trusts more than his private belief!).

Thanks!

You are right that there is also the scenario that the test givers are lying (which in this case turns out to be the truth). But this is not something Brennan in the story considers, so it can not have affected his decision. So he arrived at the correct answer, but did so by faulty logic. His two errors (not considering one possible scenario, and assigning wrong odds to the two scenarios he does consider) just happen to cancel out. It would certainly be a way to fix this story: Let Brennan first realize that he should trust everybody else over himself, and then realize that the examiner may be lying.

Though there remains a problem. If the conspirators are lying, it is not clear what answer they want. It may be a test to see if he can withstand peer pressure, but it might also be a test to see if he is willing to entertain the notion of being wrong!

Finally, yes, you are absolutely right that holding a believe because others hold it does not constitute proof. So perhaps the most rational answer would be: “My own independent calculation tells me that the answer is 2 in 9, and for the purpose of establishing a consensus opinion on this question, that is my answer. However I do not think that my evidence is enough to shift the consensus opinion away from the answer of 1 in 6, and thus this is what I shall consider the correct answer, despite my own intuition”.

But it is! He recalculates—aloud, which makes him less likely to repeat a mistake, and more likely to catch it if he does—and then, reaching the same conclusion as before, gives it again. He thinks he might have made a mistake, which is a reasonable thought, so he works it out again.

In other words,

but he does the correct thing for both of those scenarios. He entertains the notion of being wrong, and calculates his odds publicly, where anyone could point out to him if he has found that 4 times 5 is 12, but, finding the same conclusion as before, he stands up to peer pressure.

But in fact, in the story neither of those hypotheses hold. No-one is making a mistake.

I like the test. It seems to have multiple levels, each of which Brennan passes:

Can you do a simple bayes theorem calculation?

Can you resist conformity bias when necessary?

Can you spot when you’re fed bad data?

ah, i see the problem. they only specified the proportion of humans are female.

Presumably Brennan knows their own gender (they are “one of the humans in this room”). The self-include skews all the maths in a nasty way. (three quarters in the room are women, which means that 12 of the 15 other people are women which means that …)