Dispel your justification-monkey with a “HWA!”

I’m going to use a couple of words in this post that might not be immediately clear to some people. One of them is “justification”. Another is “acceptance”. I would like to suggest that if you think I’m saying something stupid when I’m using those words, that you instead consider what meaning I might be using for those words such that I’m not saying something stupid. My meanings, I think, are pretty clear if you look for them.

If you want more detail on “justification”, see this blog post on Causal Explanations vs Normative Explanations for an in-depth explanation.

Justification—ie a normative explanation as opposed to a causal one—is sometimes necessary. But, for many of us, it’s necessary much less often than we feel it is.,

The reason we justify more often than we need to is that we live in fear of judgment, from years having to explain to authorities (parents, teachers, bosses, cops (for some people)) why things went differently than they “should have”. This skill is necessary to avoid punishment from those authorities.

We often offer justifications before they’re even asked for: “Wait I can explain—”

With friends, though, or in a healthy romantic partnership, or with people that we have a solid working relationship with, it is quite apparent that this flinch towards justification is actually in the way of being able to effectively work together. It is:

unhelpful for actually understanding what happened (since it’s a form of rationalization, ie motivated cognition)

an obstacle to feeling safe with each other

a costly waste of time & attention

And yet we keep feeling the urge to justify. So what to do instead? How to re-route that habit in a way that builds trust within the relationships where justification isn’t required? How to indicate to our conversational partners that we aren’t demanding that they justify?

There are lots of ways to do this—here’s one.

Fundamentally, the issue with justification is that it’s an attempt to explain why we’re in the world that we’re in, as opposed to being in the world that we “should be” in. It indicates, therefore, that there’s a lack of acceptance of what is already real . There might be causal reasons to be understood about why what happened happened and how to do things differently in the future, but in order to actually See those without rationalizing, you first need to accept where you in fact are.

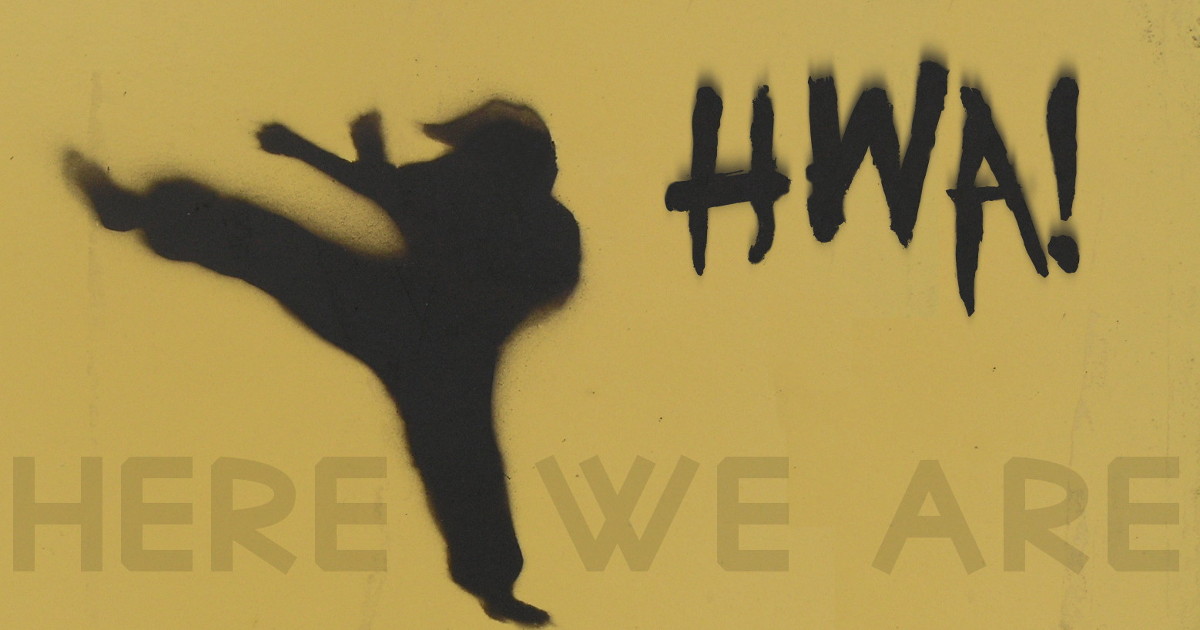

This is where “HWA!” comes in. In all caps, it sounds like a kiai , which is the japanese martial arts term for a short yell used when performing an strike. Since “hwa” is a mental move that can dispel the justification monkeys that get in the way of us co-thinking clearly, it kind of is a kiai! However, in this case the power of the sound comes from the power of the meaning.

“HWA” stands for “Here We Are”

And “here we are” is a simple, pure expression of acceptance of the reality of the present as it is. This pops out of the justification frame.

(For those tempted to get up in arms about my use of the term “acceptance”, I don’t mean the thing you think I mean. “Acceptance,” as I’m using it, doesn’t mean “allowing things to stay the same”, it means not having a sense of “this should already be different than it in fact is”. It’s too late. The present is already here! Refusing to perform this kind of acceptance here is a form of denial or regret or some other confusion.)

Here’s how to use it:

Example 1: self

The simplest situation is actually to use it with yourself. Perhaps if you catch your inner rebel attempting to justify something to your inner dictator, or just more generally you find yourself feeling that things should not be as they are . Here are some sample phrasings:

“Ahh shit I forgot to do the thing. Well, hwa.”

“Man I really haven’t been focused today. *breathe* …hwa.”

“What?! It’s noon already? I was gonna get up at—hwa. Here we are. It is noon. What now?”

In all of these cases, you’re taking a moment to let in the reality of what is so. This step is a necessary precondition to figuring out what is next. Without it, you’re just flailing.

Example 2: avoiding interpersonal blame

Alice: Man the grocery store was crowded. Anyway, here’s the Thing you said to pick up.

Bob: Oh, no, this is X Thing, this won’t work at all for the Recipe. It needs to be Y Thing.

Alice or Bob: So HWA! What do we do now?

What this does is dispel the need to figure out whose fault it was that Alice got X Thing instead of Y Thing. Did Bob assume Alice should have known that Recipe needed Y not X? Was that a reasonable assumption? Did Bob explicitly say “Y Thing”, and Alice didn’t hear? Did Bob use a synonym for Y Thing that Alice didn’t recognize? etc, etc, etc.

The answers to these questions may or may not be important, but in any case, justification is a form of rationalization and is therefore not a way to actually find the real answers to those questions.

Also, while acute time pressure stresses out your inner monkeys and tends to increase blame in these situations, the blame and justification monkey patterns are going to be in the way of actually resolving the situation by going out to get some Y Thing or finding an alternative approach, which is important when time is of the essence!

Example 3: avoiding implicit accusation

What do you do when you’re already partway into an explanation (which could easily become a justification or defense?) You can use “hwa” for that too.

If you’ve got a decent amount of flow with the other person, you can sometimes combine “hwa” with a small piece of information, to communicate your understanding of a situation without that information acting as bait for the justification monkey.

You can imagine a conversation that happened a few hours prior to the one in Example 2:

Alice: Anyway, before you go back to work, shall we check in about any food you might want me to pick up for the party tomorrow?

Bob: Oh the party is moved to tomorrow? I missed that.

Alice: I think I mentioned it… but hwa. Anyway, groceries? Snacks?

It’s mildly helpful info for the parties to have common knowledge that Alice believes she said it already. But without the “hwa”, Alice’s initial impulse to say “I think I mentioned it” can easily be read as a defense on Alice’s part, implying an accusation of B.

From this space of opposition, if B is inclined towards self-blame, they might be tempted to say “Sorry! I should have listened more closely when you were talking about the party earlier. I was distracted because I was wondering if Jamie was gonna be there.” Conversely, if they are inclined towards other-blame, they might be tempted to protest “I’m pretty sure you didn’t! Or if you did then you should have made sure I was listening when you said it...”

What Alice saying “here we are” indicates here to Bob is “whether I said it or not, whether you heard it or not, it’s okay. We don’t need to fight.”

In Practice

One practical question is: does it make sense to say “hwa” or to say a full on “here we are”?

The short answer is: use both.

In cases where there isn’t common knowledge about the “hwa” concept, you’ll naturally want to say “here we are” so that people have the slightest idea what you’re saying.

And honestly, even if people never used the abbreviation, I still think that crystallizing this concept as “hwa” makes it more memorable as a move and therefore also easier to transmit as a meme.

In addition, I think that in text-based conversations (ie where the spelling of “hwa” is easy to see but tone of voice is not) hwa has a particular couple of advantages, provided that both conversationalists know what it means already. (Maybe use the full phrase “here we are” the first time, and then also link to this post.)

It satisfies the Sparkly Pink Purple Ball Criterion. “Here we are” can mean lots of things, but “hwa” is not a phrase likely to be used by someone who hasn’t read this post (or heard about this usage), which means it will prompt awareness more.:

Relatedly, when talking aloud, the tone of voice used to say “here we are” matters. In the context of chat conversation, there’s no tone, so it helps to have a more distinct phrase

It is quick to type! In a fast-paced chat conversation, typing 3 characters instead of 11 makes a difference. It makes the thing easier to say and also means that it can more easily pop in as a kind of interruption of what seems likely to lead to justification.

Note that it’s not enough to say the phrase. You have to mean it. You have to actually accept what has happened and allow yourself to be with what’s real in the present. If you need help letting go of your concept of how things should have gone, read Transcending Regrets, Problems, and Mistakes.

Also, a general tip with stuff like this: if someone tries to use “hwa” and either party slips up and you ends up getting pulled into a justification loop, that’s okay too . It’s part of the learning process. And, if the trust is available, it is important also to give them feedback if they seem to be saying one thing (”no need for justification”) and meaning another (”but things are not okay unless I get a justification”). Just… give that feedback once you’re already back on the same page, feeling good together, not while the justification pattern is live.

This post is crossposted from malcolmocean.com.

People have recently discussed short words from various perspectives. While I was initially not super-impressed by this idea, this post made me shift towards “yeah, this is useful if done just right”.

Casually reading this post on your blog yesterday was enough for the phrase to automatically latch on to the relevant mental motion (which it turns out I was already using a lot), solidify it, make it quicker and more effective, and make me want to use it more.

It has since then been popping up in my consciousness repeatedly, on at least 5 separate occasions after I have completely forgotten about it. Once, taken to the extreme, it moved me directly into a kinda “fresh seeing” or “being a new homunculus” state of mind, where I was looking at a familiar landscape and having long-unthought thoughts in the style of “why do all these people walk? flying would be more useful. why is everything so slow, big, and empty?”.

To summarize: I think this name hit right in the middle of some concept that already badly “wanted” to materialize in my mind, and also it managed to be more short and catchy than what I would have come up with myself.

Good job! Let the HWA be with you!

I think I more or less try to live my life along the lines of HWA, and it seems to go well for me, but I wonder if that says more about the people I choose to associate with than the inherent goodness of the attitude. HWA works when people are committed to making things go better in the future regardless of whose fault it is. But not everyone thinks that way all the time. Some people haven’t acquired a universal sense of duty, they only feel duty when they attribute blame to themselves, and feel a grudging sense of unfairness if asked to care about fixing something that isn’t their fault. HWA would not work for them, unless they always understood it to mean “other person’s responsibility” and became moral freeloaders.

Even among those better suited to HWA, I think it’s still less than ideal, because it suppresses consensus-building. I think inevitably people will still think about whose fault something is, but once someone utters “HWA,” they won’t share their assessments. When people truly honor the spirit of HWA this won’t matter, because they won’t ascribe much significance to guilt and innocence, but the stories we tell about our lives are structured around the institutions of guilt and innocence, and by imposing a barrier to sharing our stories with one another, we come to each live our own story, which I fear is what tears communities and societies apart. HWA may be good for friendships, but I’m not sure it’s good on larger scales of human interactions.

This is an important point, and speaks to some of the concerns I had when reading the OP.

I, for example, am one of the people you mention who “haven’t acquired a universal sense of duty” (nor do I have any plans for acquiring one; though this is a longer discussion, for another time). It seems to me that blame is important. We often speak of it disdainfully, and the word certainly has negative connotations, but it’s absolutely critical, in many, many situations, to be quite clear about whose fault something is.

Why? Because without apportioning, and accepting, responsibility, we can’t change future behavior.

I would be rather frustrated, if I were Bob, in the example scenarios Malcolm gives. Alice has done a bad or a wrong thing. Upon discovery of this, she says ‘hwa’, indicating that she has simply accepted the new reality, and so should I, and… what? That’s it? No accountability? (The line “what do we do now?”, in particular, is somewhat insulting; it is not ‘we’ who erred, after all, but you! —thus would I think, were I Bob.) What happens the next time the same thing happens? Am I, Bob, supposed to just “accept reality” no matter how many times Alice messes up and does a thing that harms or inconveniences me, and does Alice owe me absolutely nothing for her mistakes? That way lies the road to exploitative relationships, resentment, and the breakdown of critical social structures (both within relationships and in communities).

Conversely, if I were Alice, I would feel guilt and shame if I spoke in the way example-Alice speaks, and rightly so. Alice has made a mistake, and wronged Bob thereby. In a small way, yes; nothing requiring the rending of garments and the pulling of hair, certainly. Still, the large is made out of the small, and the small in time becomes the large; so with patterns of behavior, and so in relationships. Were I Alice, I would feel compelled to (a) admit fault, and (b) either offer to take on the responsibility of correcting the situation, or, if this is not feasible or applicable, take credible action to prevent a re-occurrence of that sort of mistake.

It seems like “HWA” is a rejection of all of that, and thus, is a rejection of responsibility for one’s actions, and of obligations, not to some ‘universal duty’, but to very specific people with whom you interact and have some sort of realtionship with. Is this an unfair characterization? If so, why?

If Alice has, to use the phrase I used originally, “aquired a universal sense of duty,” then the hope is that it is less likely for the same thing to happen again. Alice doesn’t need to feel guilty or at fault for the actions, she just acknowledges that the outcome was undesirable, and that she should try to adjust her future behavior in such a way as to make similar situations less likely to arise in the future. Bob, similarly, tries to adjust his future behavior to make similiar situations less likely to arise (for example, by giving Alice a written reminder of what she was supposed to get at the store).

The notion of “fault” is an oversimplification. Both Alice’s and Bob’s behavior contributed to the undesirable outcome, it’s just that Alice’s behavior (misremembering what she was supposed to buy) is socially-agreed to be blameworthy and Bob’s behavior (not giving Alice a written reminder) is socially-agreed to be perfectly OK. We could have different norms, and then the blame might fall on Bob for expecting Alice to remember something without writing it down for her. I think that would be a worse norm, but that’s not important; the norm that we have isn’t optimal because it blinds Bob to the fact that he also has the power to reduce the chance of the bad outcome repeating itself.

HWA addresses this, but not without introducing other flaws. Our norms of guilt and blame are better at compelling people to change their behavior. HWA relies on people caring about and having the motiviation to prevent repeat bad outcomes purely for the sake of preventing repeat bad outcomes. Guilt and blame give people external interest and motivation to do so.

This “universal sense of duty” didn’t prevent Alice from committing this mistake in the first place, so—in the absence of any credible signal to this effect, or specific action to ensure it—why, exactly, should we believe that it will prevent a re-occurrence?

Ok. But I don’t see that in the OP’s examples. If you acknowledge that Alice should adjust her behavior to prevent similar future situations, then we’re halfway there. But that is important; and it is a pre-requisite to any offer by Bob to also adjust his future behavior to prevent Alice from making similar mistakes.

The other half, however, is the notion of compensating the wronged party for one’s mistakes or violations of one’s obligations. You ignored that part of my question, but it’s at least as important as the other part. Do you not think that those who are at fault ought to (whenever possible) compensate those that have been harmed by their actions?

Edit: Corrected wording which erroneously implied that adrusi was the OP.

What you seem to be vaguely gesturing towards, in your last sentence, but what really deserves to be named explicitly and confronted head-on, is the notion of incentives.

I have sometimes said that if you get nothing else from all the disciplines that study people and the patterns in which we interact—from psychology to sociology to economics to game theory—you should at least get this:

You get what you incentivize.

The notions of responsibility, obligation, fault, etc., are how we incentivize people to care about the consequences of their actions. Guilt and shame (and related emotions, such as outrage-at-betrayal) are the mechanisms, given to us by biological and socio-cultural evolution, that implement that caring in our minds—that place it firmly in ‘System 1’.

Your idea relies on people being saints. They’re not. You get what you incentivize.

I absolutely get that incentives matter. I also think that responsibility and accountability are important, and my proposal of “hwa” is not intended to suggest otherwise.

I will point out, however, that guilt/shame/punishment etc have additional incentive costs that are often unrecognized: they incentivize people to deceive each other and themselves. If I am navigating by avoiding punishment or avoiding guilt (an internalized form of social punishment) then I’m incentivized to avoid taking responsibility so as to avoid that punishment: both recognizing what I’ve done socially, because if I did then others would punish me, and also recognizing what I’ve done internally, because if I did then I would feel bad.

As you say: you get what you incentivize. And I want to build my relationships and my sense of self in such ways that deception is not incentivized. Therefore, taking a post-blame approach to responsibility.

“Hwa” does not assume that people are saints. It does, however, assume that they care. This is a decent assumption for most relationships, and if it’s not true, I recommend getting out of that relationship, whether business, romantic, or otherwise.

(This comment thread isn’t a context where it’s making sense to me to attempt to bridge all of the inferential distance that we’re working with here, but this response was something I could manage. I am going to continue to write on this subject, and I value the articulations of the gaps between my explanations and what-I-am-trying-to-say, as provided by Said and others.)

Quite so, which is why we have very strong moral intuitions that such deception constitutes defection—even betrayal. It’s also the reason why ‘integrity’ is seen as a virtue (and one of the highest virtues, at that).

Under “HWA”, it seems to me, there is indeed no incentive for deception, but only because there is no incentive to take responsibility. That’s a textbook case of “throwing the baby out with the bathwater”.

Again: quite so, and I second the recommendation. But just as we have laws to keep honest people honest, we have incentives to keep people caring who care to begin with—because most things that both matter and that we can affect happen on the margin, not at the tails. And more: show me a person for whom incentives make no difference, and I will show you a saint.

I refer again, as I did in my earlier comments, to your own examples. In what way is Alice taking responsibility for her actions? Does she make restitution, and does she even recognize that she ought to do so? Does she take credible, costly steps to ensure that the transgression will not re-occur? If she does neither of these things, then in what what sense can she be said to have taken responsibility?

You’re missing a critical point:

Alice’s behavior is socially agreed to be blameworthy, because there exists a social norml that Alice had the obligation not to behave as she did. Bob’s behavior is socially agreed to be perfectly OK, because there exists a social norm that Bob had no obligation to act otherwise than he did.

Crucially, these are pre-existing norms, of which both Alice and Bob were aware—not any sort of arbitrary, post-hoc judgments.

A person, such as Alice, is at fault when she violates an obligation that she knows she has, or acts otherwise than she knows she should (where ‘should’ means “acknowledges an obligation to behave this way”).

No. We couldn’t. The norm is: did Bob have an obligation to do X, and did he violate that obligation by failing to do X? Then Bob is at fault. Otherwise, he is not. That is what fault is.

The reason Alice is at fault here isn’t arbitrary, and the judgment of fault is not itself, directly based on some arbitrary norm. Alice had an obligation—which she has acknowledged that she had, and which she knows that she violated. That constitutes fault. If she had not had this obligation—that would be different.

We could have different norms for who has what obligations. That is irrelevant to the matter at hand, because whoever has whatever obligations, the fact is that they are known in advanced and (in your examples, and in most similar real-life cases) acknowledged after the fact. That means that changing the norms concerning who has what obligations cannot change my analysis of the situations.

Indeed, Bob does have this power. The question is, why does it fall to Bob, to use said power? Why not Alice? And if Alice does not give a satisfactory answer to this question, then it seems to me that Bob also has—and will (or, at least, should) give serious thought to using—another power that he has: the power of not associating with Alice henceforth, having written her off as an unreliable, untrustworthy person, lacking in integrity or a sense of fairness or justice.

I appreciate the point you’re making in your second paragraph. I think that the structures you’re pointing at are something that we’re on the same page about.

Most of my energies are focused on the creation and development of contexts where post-blame/post-fault (essentially what you called “the spirit of HWA”) is something that everyone is committed to, and I think that within such a context, “HWA” is actually helpful for consensus-building, as it gets the judgments out of the way so that the details can be explored together, and the parties can figure out what happened, why, and what to do next, and what collective story to tell about it—a story that doesn’t have to invoke the guilt vs innocence dichotomy at all!

But you’re making a great point about how HWA (like pretty much any tool) can also be used coercively, to shut down people whose perspectives need to be heard in order for the group to function effectively.

I think it’s harder for (eg) business relationships than friendships, but all the more important because of it. But yeah, in order for it to facilitate the sharing of stories, you need the post-blame mindset, not just one little verbal tool. And you need that to be built into the context, not just something that’s incidentally & inconsistently present.

This is similar in a lot of ways to how rationality is fundamentally a way of thinking not a collection of tools. If you aren’t truly truth-seeking, then you can use all of your rationality tools for rationalization. If you’re not seeking to get out of coercive dynamics, then you can use HWA for obfuscation.

(I want to note that a lot of the terms I’m using here (particularly “coercive”) are sort of jargon on some levels; they have quite specific meanings to me that may not be apparent. I shall write more posts to explain these; in the meantime I figured it would make sense to write some sort of response here.)

Accepting the world as it is now not how it should have been, without assigning blame, and looking for ways to steer it toward a better future is a very useful way to live. It is also anything but easy. Regrets, grudges, self-blame are all too common, and there is something both biological and cultural in needing those. I like your idea of having a short catchy way to express this future looking approach, whether hwa takes off or not.

Thoroughly agreed that it’s worth doing and also really hard.

Based on several years of experience of trying (and succeeding, to a large extent) to live without blame, in a context where others are doing the same, my read is that blame isn’t a biological imperative. I would say something like… “meaning is a biological imperative (for humans)” and then “many of our main cultural meaning narratives are blame-based”. But post-blame meaning is way better. Whether “meaning” is the thing or not, I’m inclined to say that blame as such is just pica for whatever the underlying biological need is.

Hmm… I guess there’s a few dimensions to it. A necessary aspect of meaning is concepts like responsibility, accountability, etc. You can get rid of blame without getting rid of these (and since they’re necessary, you need to keep non-blamey versions in order to be able to let go of blame.)

I haven’t yet made a good write-up on exactly why one might want to let go of blame, but if you’re familiar with “Should” Considered Harmful, it’s basically the same line of reasoning.

I think you’re describing a very useful mindset here. I’ve used it myself, rather explicitly, by saying things like, “Okay. So what do we do now?” But something about the wording of, “Here we are” or “Hwa”, even in your example uses, strikes me as appearing dismissive. I can’t pinpoint exactly why. It reads/sounds like a shrug. I don’t think I would ever use this phrasing with anyone who didn’t already know of it, because I wouldn’t want to give the impression that I’m dismissing the other person’s emotions.

I love the concept, very useful for one’s own mental hygene to notice slipping into a justification mindset and I expect if you manage to put it to regular use in social situations, it can really become the equivalent of some oil on the gears of tedious and annoying conversation.

I sometimes have to deal with people who are always late and never ever get anything done on time or as promised, possibly due to procrastination, and their instinct is to justify it because it seems that their entire strategy of getting through life is built around the concept of getting around responsibility by always justifying everything. In fact though, at this point their constant justifications annoy me even more than the fact they they don’t get it done on time, which in such cases I already assumed and factored in anyway. For such cases I find I’m already used to cutting their BS shorter with a very close variant of HWA: “Oh well, what’s done is done. How do you think we should deal with it?”.

I remember the phrase being used many years ago in an episode of “La Femme Nikita”. The head of a super-secret intelligence and black ops agency called “Section”, and his superior in an even shadowier organisation called “Oversight” have for some time been engaged in a covert power struggle with each other. By the end of the episode, it has come out into the open—as we would say here, common knowledge has been established between them about their mutual motives. The former concludes their confrontation by saying. “Well. Here we are.” Closing titles.