A stance against student debt cancellation doesn’t rely on the assumptions of any single ideology. Strong cases against student debt cancellation can be made based on the fundamental values of any section of the political compass. In no particular order, here are some arguments against student debt cancellation from the perspectives of many disparate ideologies.

Equity and Fairness

Student debt cancellation is a massive subsidy to an already prosperous and privileged population. American college graduates have nearly double the income of high school graduates. African Americans are far underrepresented among degree holders compared to their overall population share.

Within the group of college graduates debt cancellation increases equity, but you can’t get around the fact that 72% of African Americans have no student debt because they never went to college. The tax base for debt cancellation will mostly come from rich white college graduates, but most of the money will go to … rich white college graduates.

Taxing the rich to give to the slightly-less-rich doesn’t have the same Robin Hood ring but might still slightly improve equity and fairness relative to the status quo, except for the fact that it will trade off with far more important programs. Student debt cancellation will cost several hundred billion dollars at least, perhaps up to a trillion dollars or around 4% of GDP. That’s more than defense spending, R&D spending, more than Medicaid and Medicare, and almost as much as social security spending.

A trillion-dollar transfer from the top 10% to the top 20% doesn’t move the needle much on equity but it does move the needle a lot on budgetary and political constraints. We should be spending these resources on those truly in need, not the people who already have the immense privilege on an American college degree.

Effective Altruism

The effective altruist critique of student debt cancellations is similar to the one based on equity and fairness, but with much more focus on global interventions as an alternative way to spend the money.

Grading student debt cancellation on impact, tractability, and neglectedness, it scores very poorly. Mostly because of tiny impact compared to the most effective charitable interventions. Giving tens of thousands of dollars to people who already have high incomes, live in the most prosperous country on earth, and face little risk of death from poverty or disease is so wasteful that it borders on criminal on some views of moral obligations. It is letting tens of millions of children drown (or die from malaria) because you don’t want to get your suit wet saving them. Saving a life costs $5,000, cancelling student debt costs $500 billion, you do the math.

Student Debt Crisis

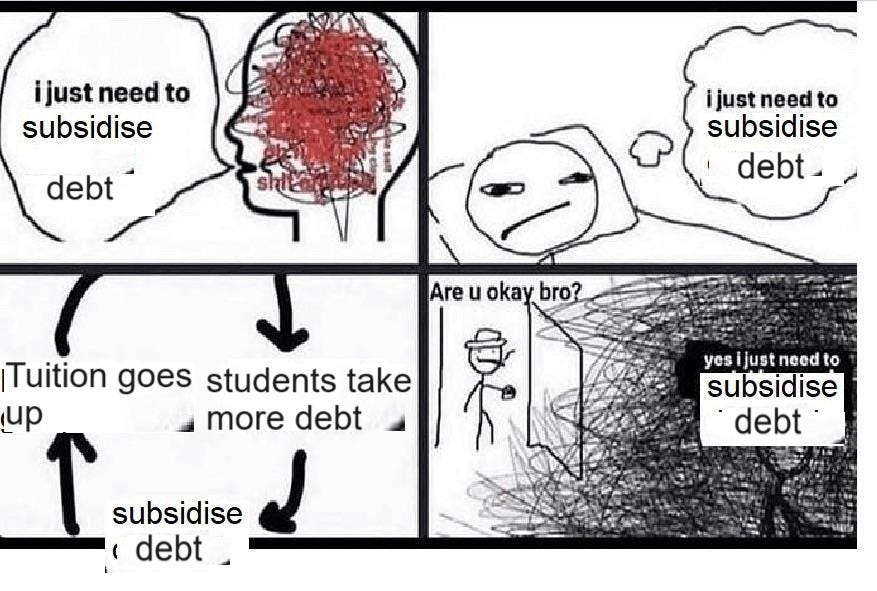

If what you really care about is stemming the ill-effects of large and growing student debt, debt cancellation is a terrible policy. If you want people to consume less of something, the last thing you should do is subsidize people who consume that thing.

But that’s exactly what debt cancellation does: It is a massive subsidy on student debt. Going forward, the legal precedent and political one-upmanship will make future cancellations more likely, so students will be willing to take more debt, study less remunerative majors, and universities will raise their prices in response.

Helping those who are already saddled with student debt by pushing future generations further into it is not the right way out of this problem.

Fiscal Conservativism

Student debt cancellation is expensive. Several hundred billion dollars has already been spent and several hundred billion more are proposed. This will mostly be financed through debt, especially since most of the costs of the program come through forgone revenue rather than direct spending.

If profligate debt financing like this continues, interest payments on debt will soon become the largest single item on the government’s balance sheet. The problem gets worse as debt gets larger since every additional piece of spending raises the interest rate on all the debt you already hold, so it can quickly spiral out of control.

There are only two ways out of this once the money has been spent: higher taxes and default. Both of these have huge costs to economic growth and freedom that are not worth paying just to bail out college students who weren’t responsible enough to study engineering and pay off their debt.

Democracy

Biden’s student debt cancellation plan does not involve Congress. Instead, he is implementing it entirely through executive order and his control over the Department of Education. An essentially equivalent plan has already been struck down by the Supreme Court but Biden’s team has found justification elsewhere in the library of babel that is the code of federal regulations.

If you think student debt cancellation is a good idea and if it has popular support, then it should be done through an act of Congress. But giving the president the ability to move a trillion dollars off of the government’s balance sheet and send the money back to his voter base without congressional approval is a risk to the democratic institutions of the US. The ends may justify the means in this case, but the next guy will have all the same means and opposite ends.

Cultural Conservatism

Student debt cancellation is a winning lottery ticket for the least deserving group of people in all of human history: American college graduates who aren’t productive enough to pay off their own debt. So not the engineers, computer scientists, doctors or lawyers who studied something valuable and paid off their debt responsibly. Nor the plumbers, electricians, and construction workers who invested in an honest trade. These groups will face big tax burdens to pay for the most indulgent and irresponsible college graduates who chose majors that are not valuable to society.

Much of that subsidy will be passed through straight to the already decadent university administrations who will use it to pour even more money into DEI-humanities majors that do nothing except produce a larger constituency for future debt relief.

Progress Studies

The progress studies criticism of student debt cancellation is sort of a combination of the effective altruist critique and the fiscal conservative one. What matters is the opportunity cost. The most important opportunity cost in this case is the lowered economic growth rate due to crowd-out and higher interest rates.

These growth rate effects compound over decades into big differences in living standards. If a tenth of the cost of debt cancellation were invested in R&D we would be several times richer in 100 years than if we spend the money subsidizing degrees with low income returns.

Divestment

A bit of horseshoe theory here. The Palestine and climate divestment protestors and the cultural conservatives agree that student debt cancellation is bad because it is a big subsidy to university administrations, although for very different reasons. Elite universities are hedge funds with classes attached. Subsidizing student debt will push more money into the massive financial machine that is funding fossil fuels and genocide.

Marxism

If we had a Marxist like Rosa Luxemberg here what she would tell you is that there can be no class more revolutionary than the proletariat. Anyone who’s not a worker is a part of the reactionary class. So a diversity officer at Harvard University is in the same class as a bank robber or a prostitute. They are part of a corrupt capitalist racket.

Student debt cancellation is a transfer to bourgeoisie college graduates. The taxes that pay for this transfer are taxes on value that is produced by labor, but claimed by capitalist owners. So even though the accounting books will show the taxes coming mainly from high income earners, this is not merely a transfer from the rich to the slightly less rich. It is a smokescreen over a transfer from the value created by workers to temporarily embarrassed capitalists.

Biden’s Campaign

This is perhaps the only value under which student debt cancellation makes sense. Doing Something about student debt and sending out checks will probably be a popular policy move. Voters don’t usually consider tradeoffs, and the costs of the policy will come long after the election this November. I’m not qualified to say whether this is the best way for Biden to secure a re-election given his resources and constraints, but it wouldn’t be crazy.

For this to be worth it, Biden’s reelection has to be worth several trillion dollars, since debt cancellation costs around one trillion and it’s benefit is just the increase in his percentage chance to win.

Except for the last three, all of these perspectives contribute to my personal stance against student debt cancellation. It’s an inefficient way to help people who aren’t in great need at great expense to economic growth and future generations of students.

There are very few sets of values that couldn’t be fulfilled to greater effect at less cost than trying to fulfill them through student debt cancellation.

I’d like to provide a qualitative counterpoint.

Aren’t these arguments valid for almost all welfare programs provided by a first-world country to anyone but the base of the social pyramid? For one example, let’s take retirement. All the tax money that goes into paying retirees to do nothing would be much better spent by helping victims of malaria etc. in 3rd world countries. If they weren’t responsible enough to save during their working years to be able to live without working for the last 10 to 30 years of their lives, especially those from the lower middle class and above, or to have had 10 kids who would sustain them in their late years, each with 10% of their income, that increases the burden on society etc. And thus similarly for other programs targeting the middle class. So why not redirect most or even all of this to those more in need?

A possible answer, covering the specific case you brought as well as the generalized version above, counterintuitive as it may be, is that the original intent of welfare seems to have been forgotten nowadays, which makes it worth bringing it back.

Welfare wasn’t originally implemented due to charitable impulses of those in power. Rather, it was first implemented to increase worker productivity, as in the programs pioneered by Bismarck in the 19th century. After that, it went on being implemented to reduce the working class’s drive to become revolutionaries, as Marx noticed would happen in his Critique of the Gotha Program, which is why he opposed such programs. And in fact, wherever extensive welfare programs were instituted early empirical observations showed they did in fact reduce the revolutionary impulse.

Add to that the well observed fact mass revolutions over the last century and half, both left- and right-wing alike, have been strongly driven by dispossessed but well-educated, and thus entitled, young adults whose social and economic status were below their perceived self-worth, and we have the recipe for why providing welfare directed at those who traditionally form a revolutionary vanguard so they don’t become a vanguard may be a reasonable long-term strategy, supposing we consider such movements, and what they result in, a net negative.

Hence the baseline question, as I see it, isn’t as much in regard to the raw economics of the issue, but on how likely a revolution in the US due to the worsening economic conditions of its young middle class versus the changing shape of the US age pyramid is, and, based on a cost-benefit analysis, how much a revolution not happening in the US over the next generation or two is worth in monetary terms. Is a US revolution strictly impossible? If it’s possible, is its likelihood high enough that reducing that likelihood is worth $1 trillion?

The same goes for all welfare aimed at this socio-economic/age-bracket group.

EDIT: Typo and punctuation corrections, and minor clarifications.

Almost all of these are about “cancellation” by means of transferring money from the government to those in debt. Are there similar arguments against draining some of the ~trillion dollars held by university endowments to return to students who (it could be argued) were implicitly promised an outcome they didn’t get? That seems a lot closer to the plain meaning of “cancelling debt”.

That’s not a part of any of the plans to cancel student debt that have been implemented or are being considered. That would definitely change a lot of the arguments but I don’t think it would make debt cancellation look like a much better policy, though the reasons it was bad would be different.

Would you mind giving the reasons you think it would still be bad if the debt was actually canceled rather than just paid by the government?

Wow, I didn’t realize just how bad student debt cancellation is from so many perspectives. Now I want more policy critiques like this.

I think debt cancellation would make sense as a sort of amnesty if it came together with some kind of reform that has the goal of preventing the situation from repeating in the future, whatever that may be. Otherwise, it’s just a one off with the downsides you mention.

The problem is that fundamentally the argument is that humanities studies have positive externalities that aren’t reflected in the salary of their graduates. I don’t dismiss this argument, though I think with humanities a lot of value is provided by the very top percentile (e.g. a handful of very capable historians will write books that will be read by millions, most others will do very little unless they teach). In that sense there may be a need to subsidize the humanity degrees, but that might be best done in the long run with things like fully paid bursaries for deserving candidates. There’s also a problem of evaluation because of course if you push such an argument you must accept some political accountability, and right now humanities are often terrible at making a case for themselves (every discussion about this I see tends to degenerate into “you can not appreciate our sophisticated knowledge, you bumpkins, but somehow studying humanities makes you a Better Person, so just accept it and thank us for our existence”, which isn’t terribly persuading. And at the very least, that the experts in subjects most closely associated with rhetoric and the understanding of human nature are so awful at persuasion is in itself concerning).

Agreed. Quite aside from questions about whether the govt should be subsiding university education (I think it should) it is clear that retroactive cancelation of debt is the wrong way to do it.

Price controls or subsidies going forwards (for new students) would have a better long term impact, and would also help poorer students more. Right now there are probably people out there who chose not to get a degree, or to get a different one, because they were worried about the debt. We can assume those people mostly were poor, and probably still are. They are the real victims of debt relief landing out of the blue. Imagine, that rich kid who took your place when you couldn’t afford uni now get a government bailout. Rich getting richer. Making the actual upfront price lower helps the next generation of these people more than it helps anyone else.

I’m skeptical a humanities education doesn’t show up in earnings. Coming out of Daniel Gross and Tyler Cowen’s Talent book, they argue a common theme they personally see among the very successful scouters of talent is the ability to “speak different cultural languages”, which they also claim is helped along by being widely read in the humanities.

I expect it matters a lot less whether this is an autodidactic thing or a school thing, and plausibly autodidactic humanities is better suited for this particular benefit than school learned humanities, since if reading a text on your own, you can truly inhabit the world of the writer, whereas in school you need to constantly tie that world back into acceptable 12 pt font, double-spaced, times new roman, MLA formatted academic standards. And of course, in such an environment there are a host of thoughts you cannot think or argue for, and in some corners the conclusions you reach are all but written at the bottom of your paper for you.

Edit: I’ll also note that I like Tyler Cowen’s perspective on the state of humanities education among the populace, which he argues is at an all-time high, no thanks to higher education pushing it. Why? Because there is more discussion & more accessible discussion than ever before about all the classics in every field of creative endeavor (indeed, such documents are often freely accessible on Project Gutenberg, and the music & plays on YouTube), more & perhaps more interesting philosophy than ever before, and more universal access to histories and historical documents than there ever was in the past. The humanities are at an all-time high thanks to the internet. Why don’t people learn more of them? Its not for lack of access, so subsidizing access will be less efficient than subsidizing the fixing of the actual problem, which is… what? I don’t know. Boredom maybe? If its boredom, better to subsidize the YouTubers, podcasters, and TikTokers than the colleges (if you’re worried about the state of humanities with regard to their own metrics of success—say, rhetoric—then who better to be the spokespeople?).

The question is more about whether a humanities degree does. It may be that the humanities “genius” is not something you catch in a bottle successfully. After all, the most successful authors don’t usually come out of a special Author College. An employer might appreciate theoretically the talent without thinking it significantly correlates with any one degree. And on the other hand, someone like Steve Jobs certainly did have quite a bit of this knack—design and branding require artistic sensibility—yet he’s mainly seen as a STEM figure.

The problem with this is that there absolutely are plenty of humanities studies that require time, impartiality and rigour, and that sort of format has all the wrong incentives for it. I think in many ways the subdivision is sort of artificial. History or philology for example are, much like natural sciences, digging towards one truth that theoretically exists, but is inaccessible save for indirect evidence. They’re not creative, artistic or particularly subjective pursuits. “Human sciences” would be a more appropriate name for them.

I think you are missing an important one. I am not sure what the title would be, but the ideology says something like: “The students chose which courses to take and loans to pay for them. The debt is to some extent self inflicted.”

I think this makes student debt very different from, for example, medical debt. Where medical debt can land unexpectedly and be unavoidable for the unlucky, student debt is taken on voluntarily.

Half a joke, but arguably debt relief should only be available to those willing to forfeit their degrees. (A sort of “We’ll return the money if you return the goods” argument). If there was a mechanism by which someone’s degree could actually be taken off them in a meaningful way this would actually be quite interesting, as it would further incentivise university’s to make sure their courses were less expensive and better value. I am now trying to imagine a world where any student at any time can go to their old university, and demand a (partial?) refund in exchange for giving back the degree. There is some decaying system, where returning the degree the day after graduation gets close to 100% refund but giving it back 10 years later gives much less.

One argument that this post misses is that a significant chunk overall, and much of the most burdensome subset of this debt (which is not the same as the highest volume of the debt), will never be collected anyway, although it still makes the holders’ lives worse. So the estimates of the costs of this policy are very inflated if they treat the forgiveness of unsecured debt as costing $1 for $1.

Still, I agree that just plain blanket forgiveness is bad policy. I don’t think that’s what was ever on the table tho? Forgiving a capped amount (I think $20,000 was proposed?) would alleviate the burdens of the most burdensome and least-collectible-anyway debt (held by low-income people, many who weren’t able to finish their degree for various reasons), while leaving people with high-priced fancy law degrees paying off their loans mostly as normal.

That said, if you think as a policy matter that college should be funded more like high school (free public option, expensive private alternative for those who want to pay), then you could be more justified in enacting that model along with cancellation as a kind of policy retroactiveness, or “reparations for victims of un-free college.”

Leftwing point of view:

Its a wealth transfer to younger people. Im fully aware that middle aged people have college debt.

Conversely wealth inequality by age is fairly extreme.

So I remain extremely in favor of student debt cancellation. Note I have never taken on any student debt so I obviously dont have any.

Why is it bad to have wealth inequality by age? Basically everyone gets to be every age, so there’s nothing “unfair” about it.

Only if you believe this is a natural stationary progression. In practice, it very likely is not, and current 20 years old won’t be as rich as current 80 years old if only they manage to survive 60 years.

Given economic growth I’d expect current 20 year olds to on average be richer than current 80 year olds by the time they are 80. If that doesn’t happen, something has probably gone wrong, unless it’s because of something like “more people are living to 80 by spending money on healthcare during their 50′s/60′s/70s”.

Albeit with wilder swings, current 80 year olds in the US lived and worked through some of the years of highest GDP growth ever. That’s not necessarily reproducible. In addition, one’s net worth isn’t just a linear function of the integral of the GDP throughout their life. For example, being able to buy a house early is a big boost because now you have capital that appreciates, possibly faster than the interests on your debt accrue. Meanwhile if you have to rent, your money disappears down a black hole. Guess what’s a big difference between Boomers and Gen Z.