I absolutely adore Robert Caro’s books: The Power Broker, which is a massive and meticulous study of the life of Robert Moses, the New York Park Commissioner who influenced urban and park design the most in the 20th century, for better and for worse; and The Years of Lyndon Johnson, a series of 4 books (of 5 planned) on the life of former US president Lyndon B. Johnson, remembered both for passing some of the biggest civil rights legislations since the end of the Civil War, and for massively increasing the American involvement in Vietnam.

But it took me some time to figure out why I love his books so much.

I’ve already discussed in a previous blog post why I see biography as so interesting: at its best, the genre builds deep, detailed, and insightful theories of people’s life, of whole periods of histories.

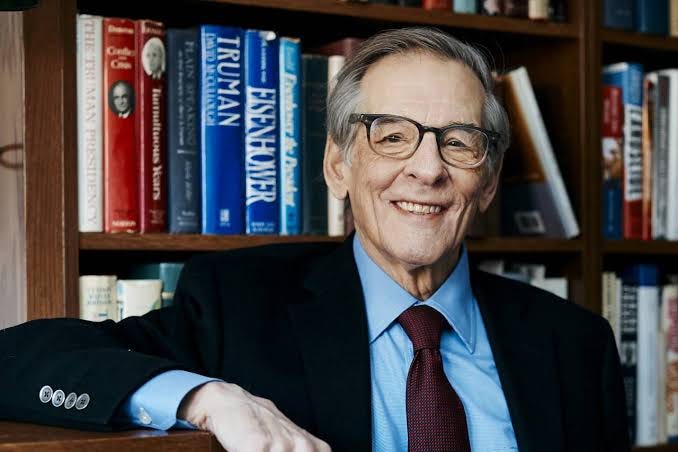

Caro definitely fits the bill: his attention to detail (“Turn Every Page” was the advice he got as a young reporter, and he took it seriously) and commitment to detailed interviews, historical methods, and living where the action happened, impresses even trained historians. In fact, he was a key inspiration behind my original blog post.

Yet he more I read and reread him, the more I feel that what puts him apart is what kind of theory he builds.

For you see, there are two extremes in the spectrum of theoretical models: the phenomenological and the mechanistic.

A phenomenological theory focuses heavily on description and compression: it defines some key concepts, elements, variables, and then links them together. Classical examples include Thermodynamics (often called phenomenological thermodynamics), Newtonian Mechanics and Macroeconomics

Whereas a mechanistic theory (also called gears-level model in rationalists circles) starts from some more basic and fundamental elements, and rederive the behavior of the system under consideration from these building blocks. The mechanistic analogous (or attempts) for the previous phenomenological theories are Statistical Mechanics (which rederives thermodynamics from the statistical properties of collections of atoms), General Relativity (which rederives gravitation from the curvature of space time), and Microeconomics (which aims to rederive macroeconomics from the aggregated behavior of simplified economical actors).

Now, by default, the kind of theory that biographers come up with are almost always phenomenological, for a good reason: they are stories, and stories are just the natural human way to compress complex social information. These stories don’t try to explain, or to rederive what happened, or to clarify what might have happened counterfactually; they simply describe the salient details in a way that can be easily interpreted and remembered.

Whereas Caro actually build mechanistic models. He also has stories and more standard narratives through his books, but he is by far the biographer I know with the most focus on mechanistic modelling.

Let’s get into an example: the first few chapters of Caro’s first book on LBJ, The Path To Power.

What Caro sets out to do is finding a good model, a detailed mechanistic model, to explain how LBJ can at the same time care enough to push through unprecedented civil rights legislation as senate majority leader and president, and yet be so clearly a ruthless politician leveraging his power and favors to get more money, more support, more power, stealing elections, and even more surprising, wanting to be seen above all as the supreme opportunist and ruthless politician.

So Caro investigates LBJ’s youth, uncovering what his subject had managed to hide so well: that from an early age, his father (once a respected politician and businessman) had lost all his money, and let his family slide down into a poverty so deep that they could only keep their house and eat from the charity of family and friends, turning LBJ and his brothers and sisters into a source of ridicule (to the point where at least one of his potential girlfriend had to turn him down because her father didn’t want her to date a good-for-nothing Johnson).

To Caro, this explains a lot of the need for pragmatism and ruthlessness in Johnson’s adult life: his parents were idealists, they were the main idealists of where they lived, the readers of books and defenders of causes, and they had failed so deeply that they had created this shameful life for their children. Johnson had seen for himself what idealism led to.

But that’s not enough for Caro: sure, Sam Early Johnson, LBJ’s father, might have been an idealist. Yet there are plenty of idealists that do succeed, and he was brilliant and loved enough to be one of those.

This is where Caro starts to dig into the geology of Caro’s birthplace: the Texas Hill Country. It turns out that it’s one of these places where you don’t want to be idealist at all, because it’s a trap.

I’ll let Caro get that through, much better than I can:

THE HILL COUNTRY was a trap—a trap baited with grass.

[…]

To these men the grass was proof that their dreams would come true. In country where grass grew like that, cotton would surely grow tall, and cattle fat—and men rich. In country where grass grew like that, they thought, anything would grow.

How could they know about the grass?

[…]

The very hills that made the Hill Country so picturesque also made it a country in which it was difficult for soil to hold. The grass of the Hill Country, then, was rich only because it had had centuries in which to build up, centuries in which nothing had disturbed it. It was rich only because it was virgin. And it could be virgin only once.

[…]

AND THEN THEY BEGAN to find out about the land.

All the time they had been winning the fight with the Comanches, they had, without knowing it, been engaged in another fight—a fight in which courage didn’t count, a fight which they couldn’t win. From the first day on which huge herds of cattle had been brought in to graze on that lush Hill Country grass, the trap had been closing around them. And now, with the Indians gone, and settlement increasing—and the size of the herds increasing, too, year by year—it began to close faster.

The grass the cattle were eating was the grass that had been holding that thin Hill Country soil in place and shielding it from the beating rain. The cattle ate the grass—and then there was no longer anything holding or shielding the soil.

In that arid climate, grass grew slowly, and as fast as it grew, new herds of cattle ate it. They ate it closer and closer to the ground, ate it right down into the matted turf—the soil’s last protection. Then rain came—the heavy, pounding Hill Country thunderstorms. The soil lay naked beneath the pounding of the rain—this soil which lay so precariously on steep hillsides.

The soil began to wash away.

[…]

It had taken centuries to create the richness of the Hill Country. In two decades or three after man came into it, the richness was gone. In the early 1870’s, the first few years of cotton-planting there, an acre produced a bale or more of cotton; by 1890, it took more than three acres to produce that bale; by 1900, it took eleven acres.

The Hill Country had been a beautiful trap. It was still beautiful—even more beautiful, perhaps, because woods covered so much more of it now, and there were still the river-carved landscapes, the dry climate, the clear blue sky—but it was possible now to see the jaws of the trap. No longer, in fact, was it even necessary to look beneath the surface of the country to see the jaws. On tens of thousands of acres the reality was visible right on the surface. These acres—hundreds of square miles of the Hill Country—had once been thickly covered with grass. Now they were covered with what from a distance appeared to be debris. Up close, it became apparent that the debris was actually rocks—from small, whitish pebbles to stones the size of fists—that littered entire meadows. A farmer might think when he first saw them that these rocks were lying on top of the soil, but if he tried to clear away a portion of the field and dig down, he found that there was no soil—none at all, or at most an inch or two—beneath those rocks. Those rocks were the soil—they were the topmost layer of the limestone of which the Hill Country was formed. The Hill Country was down to reality now—and the reality was rock. It was a land of stone, that fact was plain now, and the implications of that fact had become clear. The men who had come into the Hill Country had hoped to grow rich from the land, or at least to make a living from it. But there were only two ways farmers or ranchers can make a living from land: plow it or graze cattle on it. And if either of those things was done to this land, the land would blow or wash away.

[…]

BUT THE LAND WAS DOMINANT, and while the Hill Country may have seemed a place of free range and free grass, in the Hill Country nothing was free. Success—or even survival—in so hard a land demanded a price that was hard to pay. It required an end to everything not germane to the task at hand. It required an end to illusions, to dreams, to flights into the imagination—to all the escapes from reality that comfort men—for in a land so merciless, the faintest romantic tinge to a view of life might result not just in hardship but in doom. Principles, noble purposes, high aims—these were luxuries that would not be tolerated in a land of rock. Only material considerations counted; the spiritual and intellectual did not; the only art that mattered in the Hill Country was the art of the possible. Success in such a land required not a partial but a total sacrifice of idealism; it required not merely pragmatism but a pragmatism almost terrifying in its absolutely uncompromising starkness. It required a willingness to face the hills head-on in all their grimness, to come to terms with their unyielding reality with a realism just as unyielding—a willingness, in other words, not only to accept sacrifices but to be as cruel and hard and ruthless as this cruel and hard and ruthless land.

\- Robert Caro, The Path To Power, Chapter 1

LBJ’s father didn’t have this insane pragmatism. At the height of his social climb, he decided to go all in and buy the old family ranch, to grow cotton on it. But he ended up losing everything, seeing all the product of his efforts and courage being washed away down the massive gullies every storm, again and again. Until it broke him.

In order word, for Caro, to understand LBJ’s political life, you need to go back to the geology of the Texas Hill Country. Because he saw what it did to his father, to his family, and he learned the lesson. He learned it in his bones, in the shame and fear and need for accomplishment and power that was to prod and shape him for the rest of his life.

This model is much more mechanistic than just “he was pissed against his dad”, or even the complete lack of attempt to explain that sometimes happens in biographies. This lets us think through the counterfactual: what might have happened if the Johnson didn’t live in the hill country, but in a more hospitable part of Texas? what might have happened if Sam Early Johnson was more pragmatic, or if he was just slightly more lucky for a bit more time, failing only as his first son left the house? We’ve uncovered new underlying degrees of freedom for the explanation of LBJ’s character.

And Caro does it again and again: he writes what is considered maybe the most detailed and insightful history of the US Senate as a first chapter of book 3 in the LBJ series, just so he can explain the subtleties and magnitude of the interventions that LBJ implements as minority, and then majority leader; in The Power Broker, he digs deeply into the various stratagems Robert Moses deploys to make himself unstoppable (starting a lot of projects so he can basically force the legislature to give him funds to finish them, leveraging obscure New York state precedents to give himself massive powers, having so much more engineers and planners that he was the main one with plans ready for federal funding during the New Deal era…)

At its core, I think this is why I love Caro’s books so much: in addition to being delightful and enthralling, they actually give me deep and complex mechanistic models about topics I normally don’t think about (power, politics, legal systems…), such that I can play with them, compare them with others, potentially debate or invalidate them.

Unfortunately all the positives of these books come paired with a critical flaw: Caro only manages to cover two people, and hasn’t even finished the second one!

Have you found other biographers who’ve reached a similar level? Maybe the closest I’ve found was “The Last Lion” by William Manchester, but it doesn’t really compare giving how much the author fawns over Churchill.

I found Ezra Vogel’s biography of Deng Xiaoping to be on a comparable level.

I can confirm it’s very good!

In my view, Caro is actually less guilty of this than most biographers.

Fundamentally, this is because he cares much more about power, its sources, and its effects on the wielders, beneficiaries, and victims. So even though the throughline are the lives of Moses and Johnson, he spends a considerable amount of time on other topics which provide additional mechanistic models with which to understand power.

Among others, I can think of:

The deep model of the geology and psychology of the trap of the hill country that I mention in the post

What is considered the best description of what it was for women especially to do all their chores by hand in the hill country before Johnson brought them electricity

Detailed models of various forms of political campaigning, the impact of the press and

Detailed models of various forms of election stealing

What is considered the best history of the senate, what it was built for, with which mechanisms, how these became perverted, and how Johnson changed it and made it work.

Detailed model of the process that led to the civil rights movements and passage of the civil rights bills

Detailed model of the hidden power and control of the utilities

In general, many of Moses’ schemes mentioned to force the legistlature and the mayor to give him more funding and power

He even has one chapter in the last book that is considered on par with many of the best Kennedy biographies.

Still, you do have a point that even if we extend the range beyond the two men, Caro’s books are quite bound in a highly specific period: mid 20th century america.

I think it’s kind of a general consensus that finding something of a similar level is really hard. But in terms of mechanistic models, I did find Waging A Good War quite good. It explores the civil rights movement successes and failures through the lens of military theory and strategy. (It does focus on the same period and locations as the Caro books though...)

We’re not disagreeing: by “covers only two people” I meant “has only two book series”, not “each book series covers literally a single person”.