Laying the Foundations for Vision and Multimodal Mechanistic Interpretability & Open Problems

Join our Discord here.

This article was written by Sonia Joseph, in collaboration with Neel Nanda, and incubated in Blake Richards’s lab at Mila and in the MATS community. Thank you to the Prisma core contributors, including Praneet Suresh, Rob Graham, and Yash Vadi.

Full acknowledgements of contributors are at the end. I am grateful to my collaborators for their guidance and feedback.

Outline

Part One: Introduction and Motivation

Part Two: Tutorial Notebooks

Part Three: Brief ViT Overview

Part Four: Demo of Prisma’s Functionality

Key features, including logit attribution, attention head visualization, and activation patching.

Preliminary research results obtained using Prisma, including emergent segmentation maps and canonical attention heads.

Part Five: FAQ, including Key Differences between Vision and Language Mechanistic Interpretability

Part Six: Getting Started with Vision Mechanistic Interpretability

Part Seven: How to Get Involved

Part Eight: Open Problems in Vision Mechanistic Interpretability

Introducing the Prisma Library for Multimodal Mechanistic Interpretability

I am excited to share with the mechanistic interpretability and alignment communities a project I’ve been working on for the last few months. Prisma is a multimodal mechanistic interpretability library based on TransformerLens, currently supporting vanilla vision transformers (ViTs) and their vision-text counterparts CLIP.

With recent rapid releases of multimodal models, including Sora, Gemini, and Claude 3, it is crucial that interpretability and safety efforts remain in tandem. While language mechanistic interpretability already has strong conceptual foundations, many research papers, and a thriving community, research in non-language modalities lags behind. Given that multimodal capabilities will be part of AGI, field-building in mechanistic interpretability for non-language modalities is crucial for safety and alignment.

The goal of Prisma is to make research in mechanistic interpretability for multimodal models both easy and fun. We are also building a strong and collaborative open source research community around Prisma. You can join our Discord here.

This post includes a brief overview of the library, fleshes out some concrete problems, and gives steps for people to get started.

Prisma Goals

Build shared infrastructure (Prisma) to make it easy to run standard language mechanistic interpretability techniques on non-language modalities, starting with vision.

Build shared conceptual foundation for multimodal mechanistic interpretability.

Shape and execute on research agenda for multimodal mechanistic interpretability.

Build an amazing multimodal mechanistic interpretability subcommunity, inspired by current efforts in language.

Set the cultural norms of this subcommunity to be highly collaborative, curious, inventive, friendly, respectful, prolific, and safety/alignment-conscious.

Encourage sharing of early/scrappy research results on Discord/Less Wrong.

Co-create a web of high-quality research.

Tutorial Notebooks

To get started, you can check out three tutorial notebooks that show how Prisma works.

Main ViT Demo—Overview of main mechanistic interpretability technique on a ViT, including direct logit attribution, attention head visualization, and activation patching. The activation patching switches the net’s prediction from tabby cat to Border collie with a minimum ablation.

Emoji Logit Lens—Deeper dive into layer- and patch-level predictions with interactive plots.

Interactive Attention Head Tour—Deeper dive into the various types of attention heads a ViT contains with interactive JavaScript.

Brief ViT Overview

A vision transformer (ViT) is an architecture designed for image classification tasks, similar to the classic transformer architecture used in language models. A ViT consists of transformer blocks; each block consists of an Attention layer and an MLP layer.

Unlike language models, vision transformers do not have a dictionary-style embedding and unembedding matrix. Instead, images are divided into non-overlapping patches, similar to tokens in language models. These patches are flattened and linearly projected to embeddings via a Conv2D layer, akin to word embeddings in language models. A learnable class token (CLS token) is prepended at the start of the sequence, which accrues global information throughout the network. A linear position embedding is added to the patches.

The patch embeddings then pass through the transformer blocks (each block consists of a LayerNorm, an Attention layer, another LayerNorm, and an MLP layer). The output of each block is added back to the previous input. The sum of the block’s output and its previous input is called the residual stream.

The final layer of this vision transformer is a classification head with 1000 logit values for ImageNet’s 1000 classes. The CLS token is fed into the final layer for 1000-way classification. Adapting TransformerLens, we designed HookedViT to easily capture intermediate activations with custom hook functions, instead of dealing with PyTorch’s normal hook functionality.

Prisma Functionality

We’ll demonstrate the functionality with some preliminary research results. The plots are all interactive but the LW site does not let me render HTML. See the original post for interactive graphs.

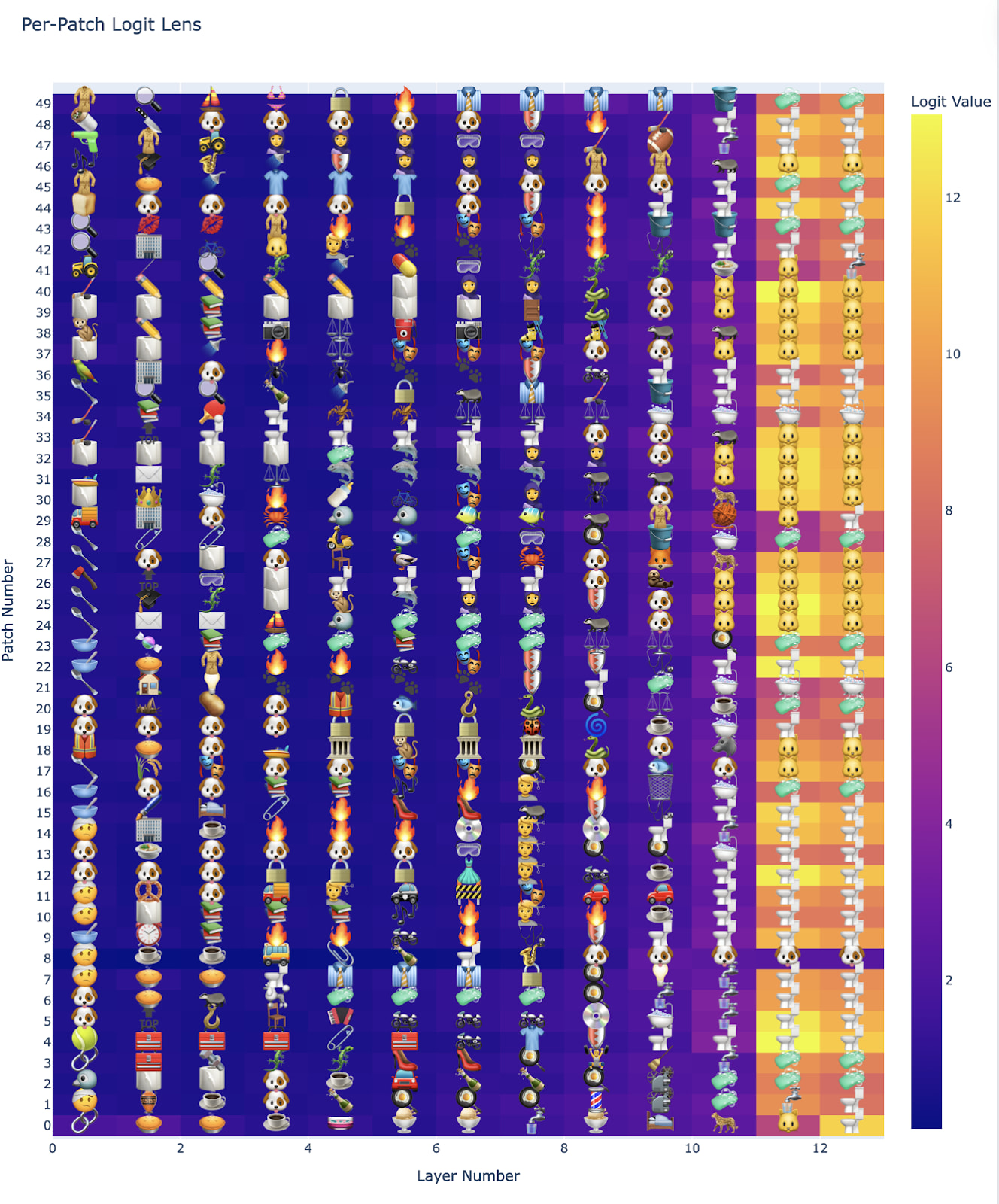

Emoji Logit Lens

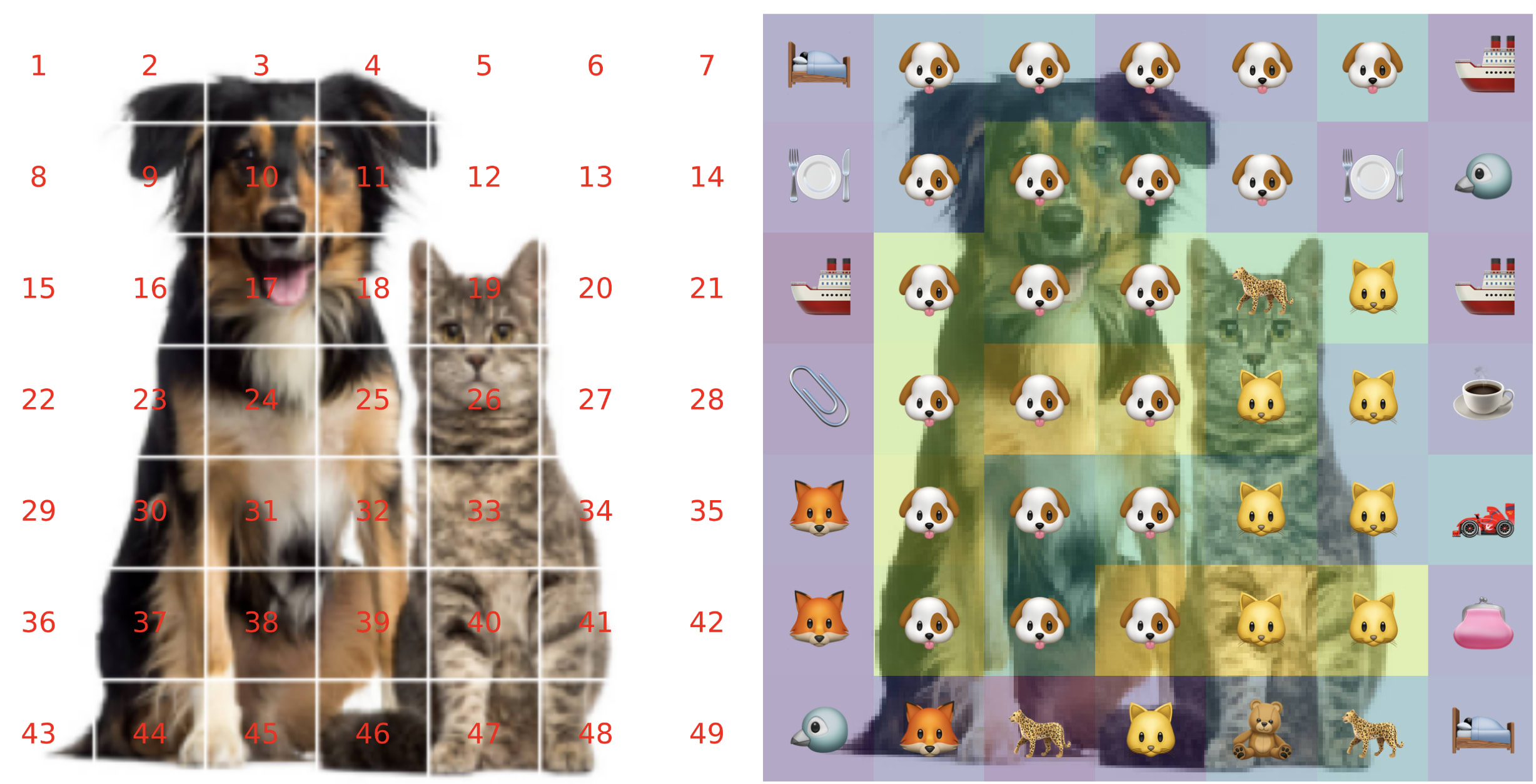

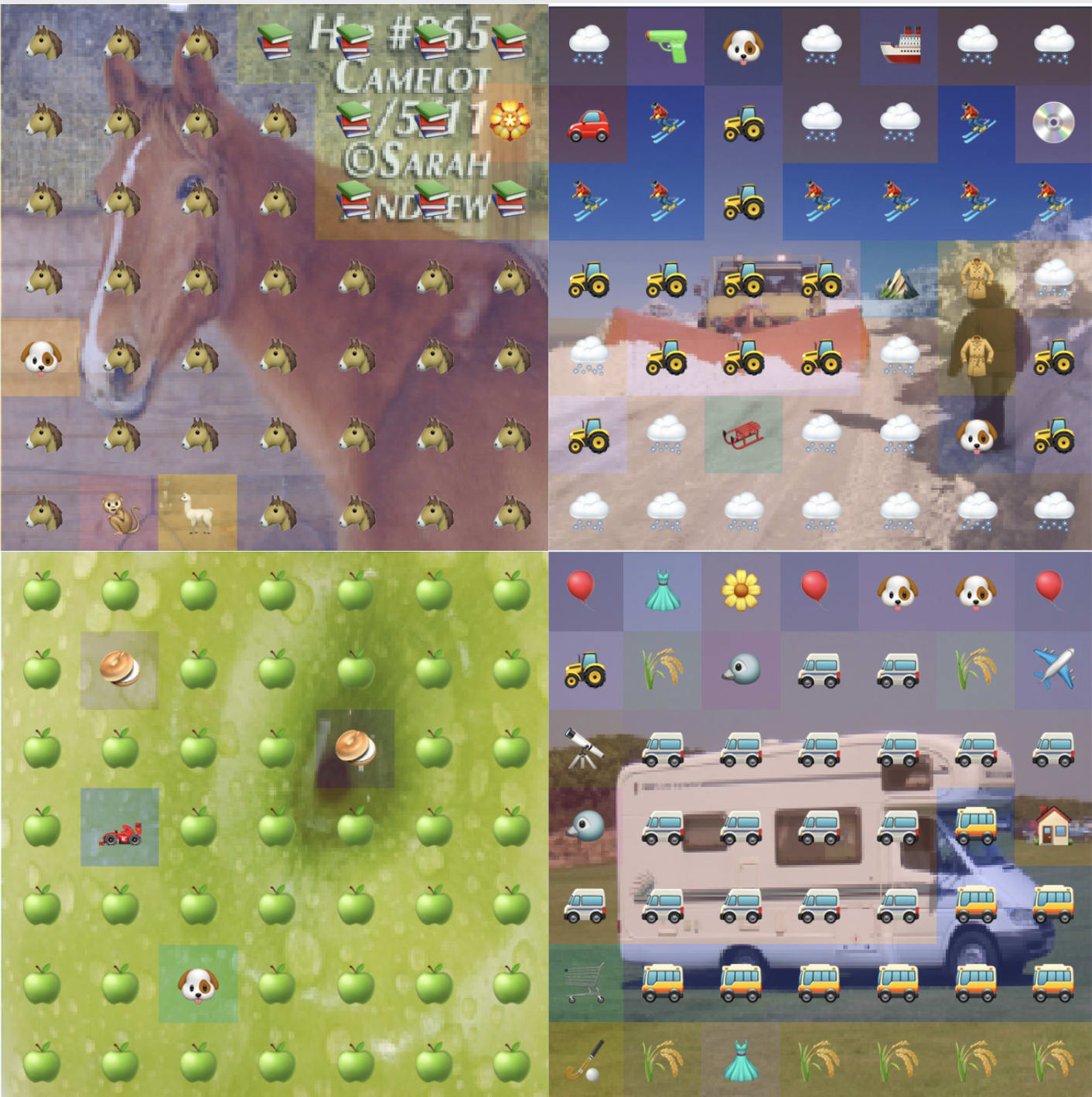

The emoji logit lens is a convenient way to visualize patch-level predictions for each layer of the net.

We treat every patch like the CLS token, and feed it into the ViT’s 1000-way classification head that’s pre-trained on ImageNet, without fine-tuning. This is the equivalent to deleting all layers between the layer of your choice and the output classification head.

For convenience, we represent the ImageNet prediction of that patch with its corresponding emoji, drawing from our ImageNet-Emoji Dictionary.

Below are the patch-level predictions of the final layer of a ViT for an image of a cat sitting inside a toilet. The yellow means that the logit prediction was high and blue means the logit prediction was low (see the Emoji Logit Lens notebook for more details).

Emergent Segmentation

One of my favorite findings so far is that the patch-level logit lens on the image basically acts as a segmentation map. For the image above, the cat patches get classified as cat, and the toilet patches get classified as a toilet!

This is not an obvious result, as vision transformers are optimized to predict a single class with the CLS token, and not segment the image. The segmentation is an emergent property. See the Emoji Logit Lens Notebook for more details and an interactive visualization.

Similar emergent segmentation capabilities were recently reported by Gandelsman, Efros, and Steinhardt (2024), who found that decomposing CLIP’s image representation across spatial locations allowed obtaining zero-shot semantic segmentation masks that outperformed prior methods. Our results extend this finding to vanilla vision transformers and provide an intuitive visualization using the emoji logit lens.

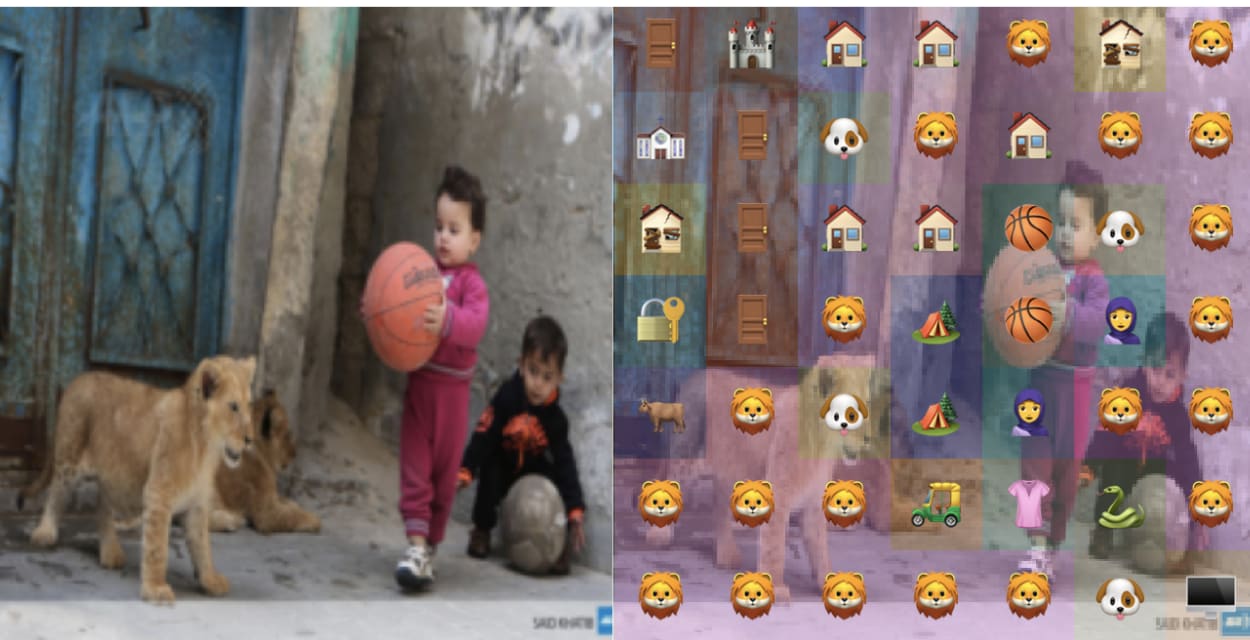

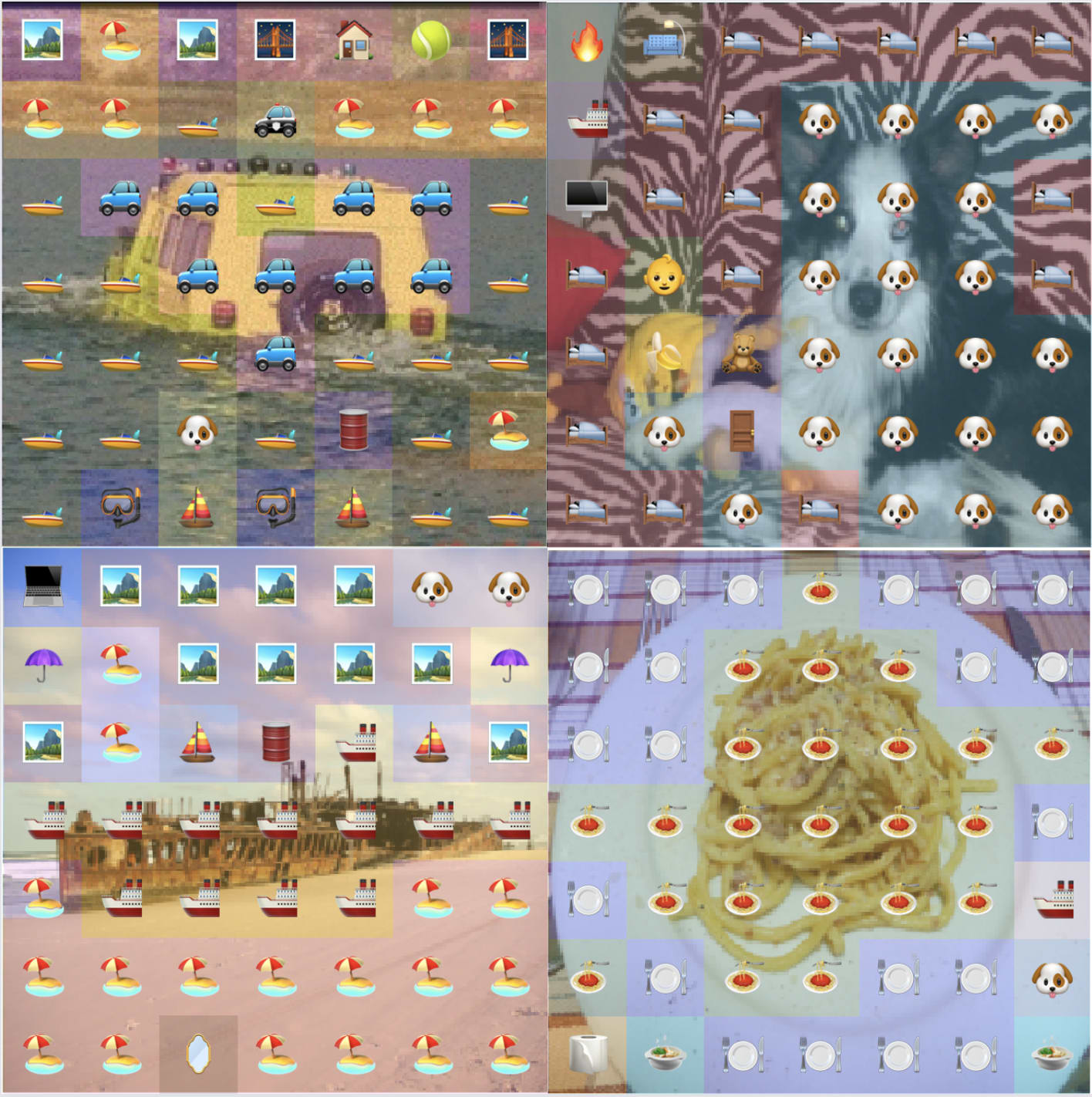

We can see similar results on other images.

(Note: For visualization purposes, I’ve changed the coloring to be by emoji class instead of logit value like above; see Emoji Logit Lens notebook for details.)

Interestingly, the net has some biased predictions (“abaya” for the children, perhaps due to their ethnicity), one consequence of only having a 1000-class vocabulary to span concept-space.

Funnily, the net thinks that the center of the green apple (above image, bottom left) is a bagel.

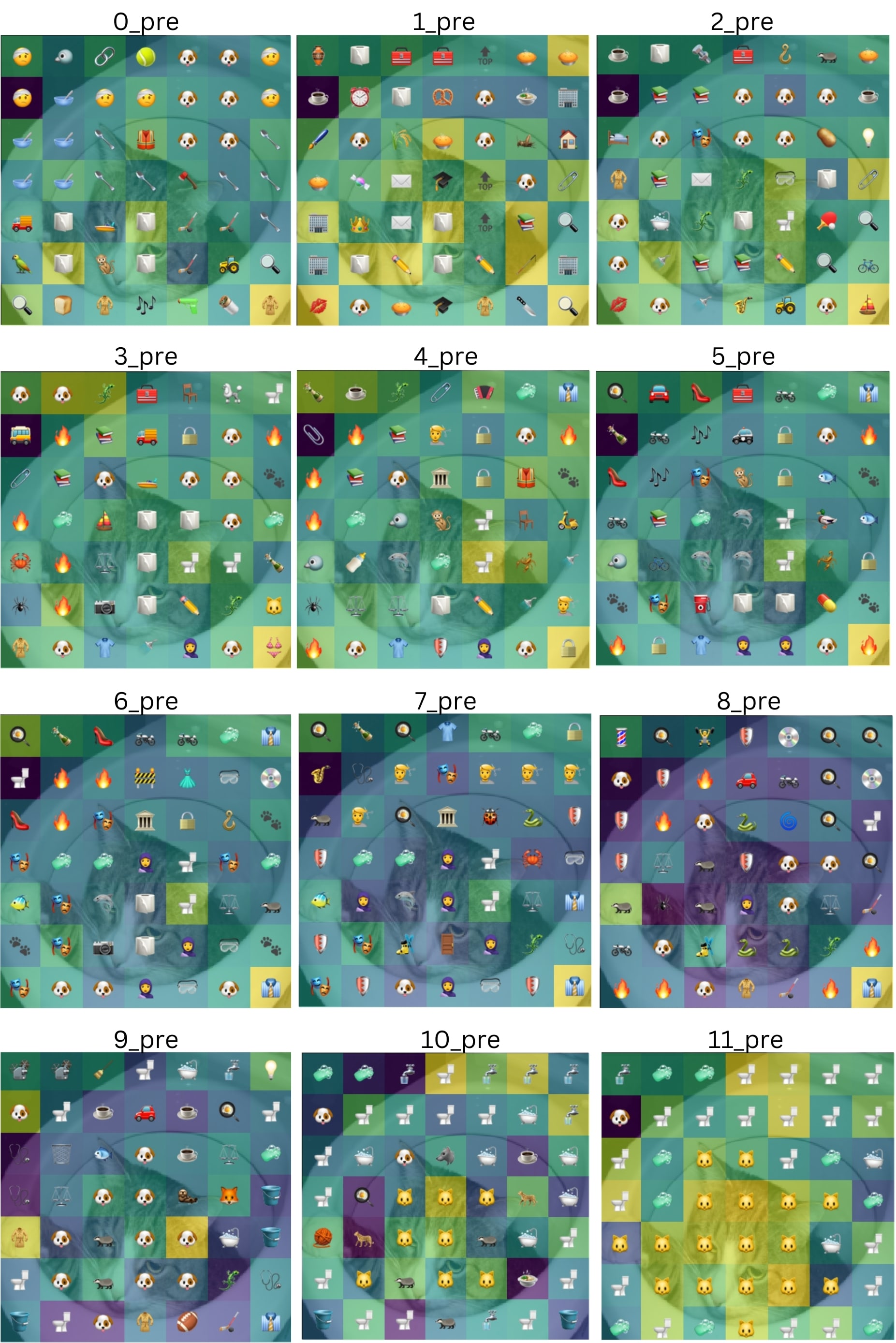

When we do a layer-by-layer logit lens, we see the net’s evolving predictions:

Interestingly, the net picks up on the “animal” at 9_pre (the residual stream before the 9th transformer block) but classifies the cat as a dog. The net only catches onto the cat at 10_pre.

This layer-wise analysis builds upon the work of Gandelsman, Efros, and Steinhardt (2024), who used mean ablations to identify which layers in CLIP have the most significant direct effect on the final representation. Our emoji logit lens provides a complementary view, visualizing how the patch-level predictions evolve across the model’s depth.

Interactive code here.

We can also visualize the evolving per-patch predictions for the above cat/toilet image for all the layers at once:

Direct Logit Attribution

The library supports direct logit attribution, including at the layer-level and attention-level.

Below, the net starts making a distinction between tabby/collie and banana at the eighth layer. See the ViT Prisma Main Demo for the interactive graph.

Attention Heads

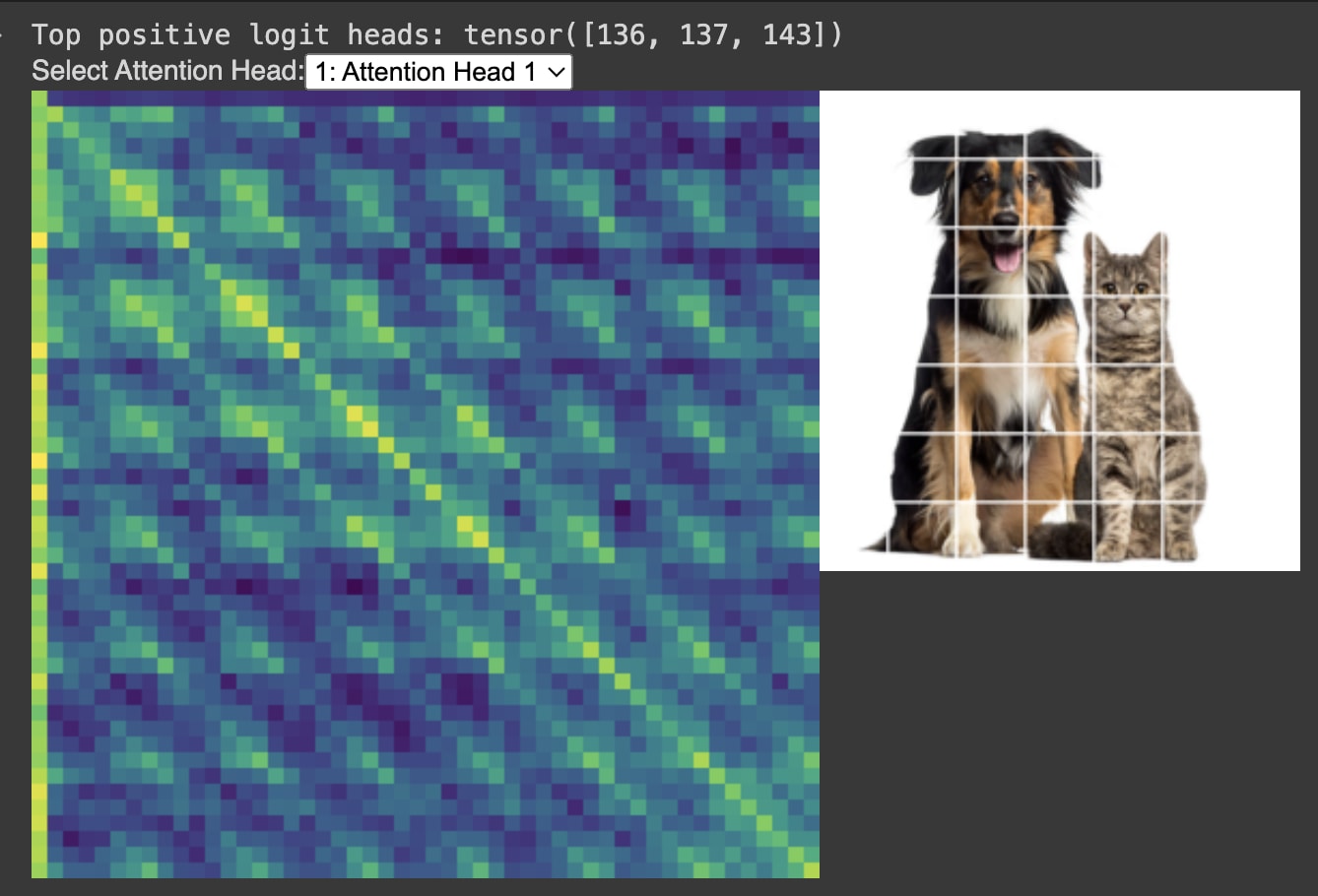

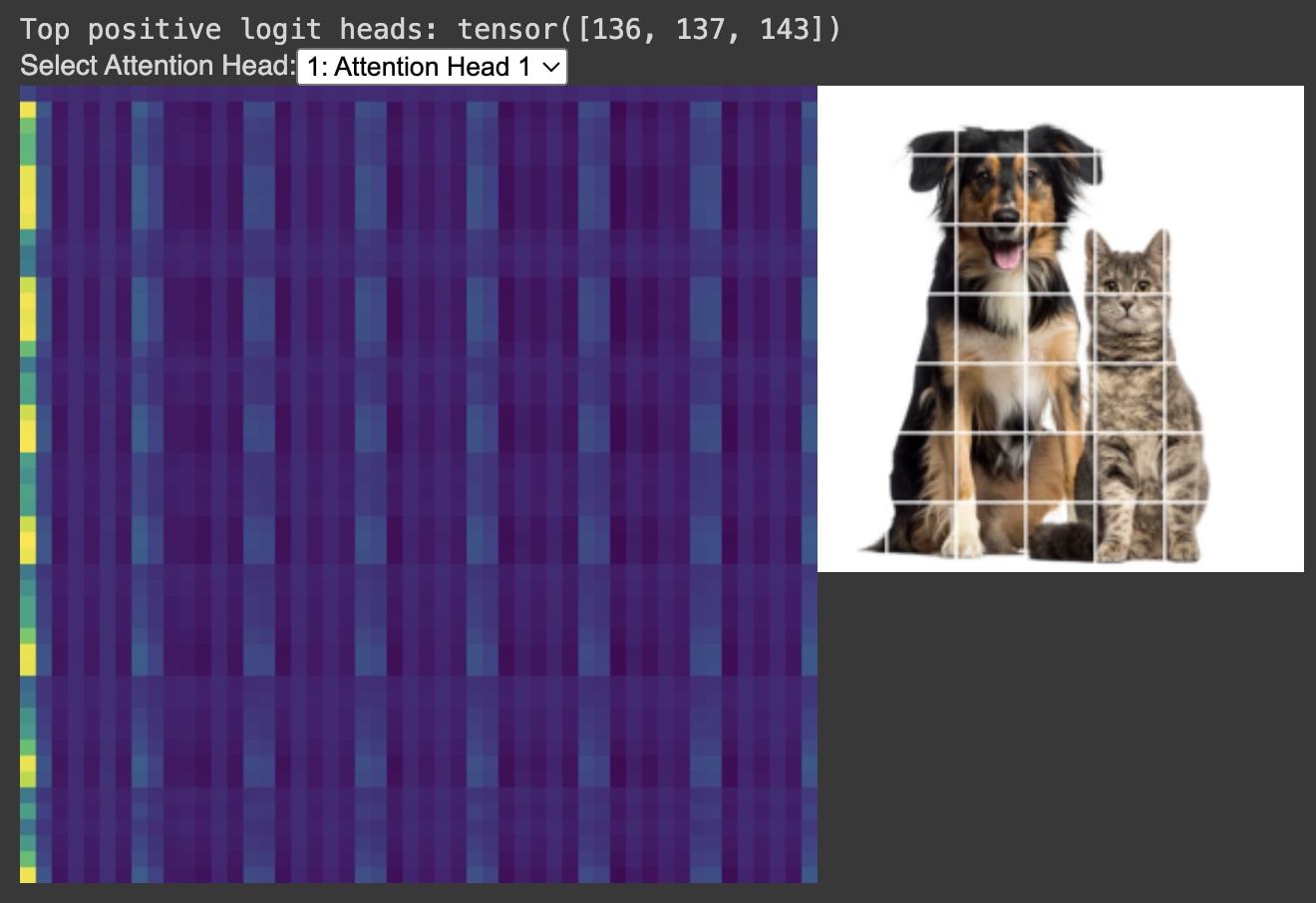

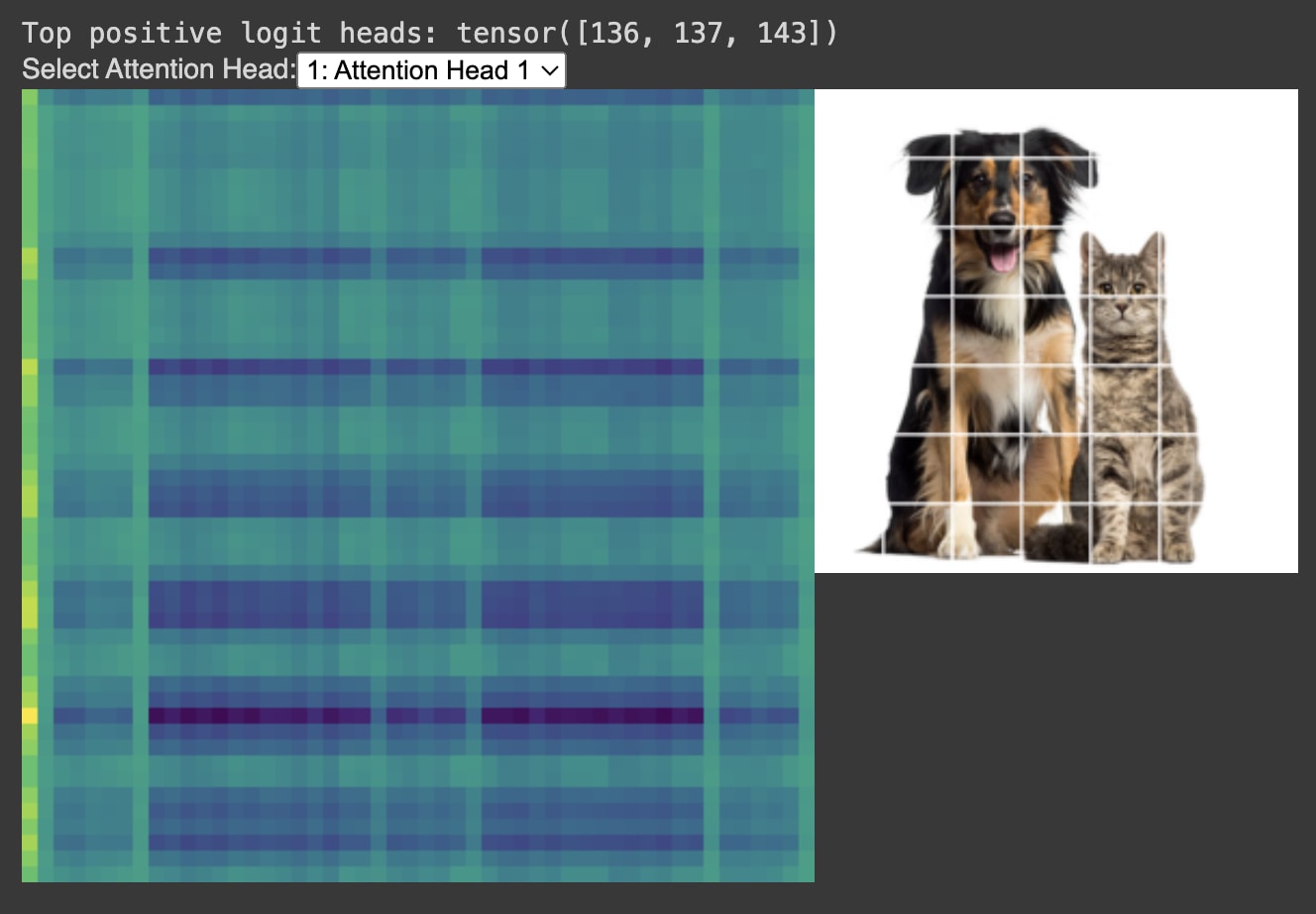

I wrote an interactive JavaScript visualizer so we can see what each vision attention head is attending to on the image.

The x and y axes of the attention head are the flattened image. The image is 50 patches in total, including the CLS token, which means the total attention head is a 50x50 square.

Upon initial inspection, the first layer’s attention heads are extremely geometric.

Corner Head, Edges Head, and Modulus Head

We can see attention heads’ scores specializing for specific patterns in the data, including what we call a Corner Head, an Edges Head, and a Modulus Head. This is fascinating because the flattened image does not explicitly contain corner, edge, or row/column information; detecting these patterns is emergent from training.

These findings echo the recent work of Gandelsman, Efros, and Steinhardt (2024) who identified property-specific attention heads in CLIP that specialize in concepts like colors, locations, and shapes. Our results suggest that such specialization is a more general property of vision transformer architectures, including vanilla models trained solely on image classification, and includes even more basic geometric properties like the coordinates of the image.

Video of the Corner Head

Activation Patching

Prisma has the activation patching functionality of TransformerLens.

The Cat-Dog Switch

I found a single attention head (Layer 11, Head 4) wherein patching the CLS token of the z-matrix flips the computation from tabby cat to Border Collie. The CLS token in that z-matrix aggregates patch-level cat ear/face information from the attention pattern.

Our activation patching results demonstrate that this technique can be used to flip the model’s prediction by targeting specific heads, providing a powerful tool for understanding and manipulating the model’s decision-making process

This result resonates with Gandelsman, Efros, and Steinhardt (2024), who showed that knowledge of head-specific roles in CLIP can be used to manually intervene in the model’s computation, such as removing heads associated with spurious cues.

Interactive code here.

Toy Vision Transformers

We are releasing nine tiny ViTs for testing (equivalent to TransformerLens’ gelu-1l) to better isolate behavior. These tiny ViTs were trained by Yash Vadi and Praneet Suresh.

ImageNet tiny ViTs 1-4 layers; Attention-Only Transformers and Attention + MLP

ImageNet tiny ViT (patch size 32, 3 layers) (This larger patch size ViT has inspectable attention heads; else the patch size 16 attention heads above are too large to easily render in JavaScript.)

The repo also contains training code to quickly train custom toy ViTs.

HookedViT

We currently support timm’s vanilla ViTs, TinyCLIP, the video vision transformer, and our own custom tiny transformers. More models will come soon based on demand!

FAQ

Is multimodal mechanistic interpretability really that different from language?

Yes and no. Vision mech interpretability is like language mechanistic interpretability, but in a fun-house mirror. Both architectures are transformers, so many LLM techniques carry over. However, there are a few twists:

The typical ViT is not doing unidirectional sequence modeling. ViTs use bidirectional attention and predict a global CLS token, rather than predicting the next token in an autoregressive manner. (Note: There are autoregressive vision transformers with basically the same architecture as language, such as Image GPT and Parti, which do next-token image generation. However, as of February 2024, autoregressive vision transformers are not frequently used in the wild.)

Bidirectional attention vs causal attention. Language transformers have causal (unidirectional) attention—i.e. there is an upper triangular mask on the attention, so that earlier tokens cannot attend to tokens in the future. However, the classical ViT has bidirectional attention. Thus, the ViT does not have the same concept of “time” as language transformers, and some of the original language mechanistic interpretability techniques break. It can be unclear which direction information is flowing. Induction heads if they are present in vision, would look different from those in language to account for bidirectional attention.

CLS token instead of next token prediction/ autoregressive loss. For ViTs, a learnable CLS token, which is prepended to the input, gets fed into the classification head instead of the final token as in language. The CLS token accrues global information from the other patches through self-attention as all the patches pass through the net.

No canonical dictionary matrix. Vision is more ambiguous and lacks the standard dictionary matrix like the 50k one for language. For instance, a yellow patch on a goldfinch might represent “yellow,” “wing,” “goldfinch,” “bird,” or “animal,” depending on the granularity, showing hierarchical ambiguity. An animal might be identified specifically as a “Border collie” or more generally as a “dog.” Beyond hierarchy, ambiguity in vision also stems from cultural interpretations and the imprecision of language. Practically, ImageNet’s 1000 classes serve as a makeshift “dictionary,” but it falls short of fully encompassing visual concepts.

Additional hyperparameters. Patch size is a vision-specific hyperparameter, determining the size of the patches into which an image is divided. Using smaller patches increases accuracy but also computational load, because attention scales quadratically with patch number.

There is a zoo of vision transformers. Similar to language, vision transformers come in many forms. The most relevant are the vanilla ViT; CLIP, which is co-trained with text using contrastive loss; and DINO, which uses unlabeled data. There is also a gallery of loss functions used, including classification loss and masked autoencoder loss. Different losses may lead to different emergent symmetries in the model, although this is an open question. For a review of important ViT architectures, check out this survey.

If there is demand, I may write up a post giving a deeper and more theoretical take on the differences on language vs non-language mechanistic interpretability.

Why start with vision transformers?

Vision transformers have an extremely similar architecture to language transformers, so many of the existing techniques transfer over cleanly.

Diffusion models are the next obvious frontier, but there will be a larger conceptual leap in designing mechanistic interpretability techniques, largely due to their iterative denoising process. I’d be happy to collaborate on this with anyone who is serious about building strong conceptual foundations here.

Getting Started with Vision Mechanistic Interpretability

It is wise to first have a strong foundation in language mechanistic interpretability, so check out the loads of resources already on this forum. The ARENA curriculum is a good place to start.

Check out these tutorial notebooks:

Main ViT Demo—Includes direct logit attribution, activation patching, and other standard mech interp techniques. The notebook has a section that switches a ViT’s prediction from tabby cat to Border Collie with a minimum ablation.

Optional:

Mindreader. A viewer for maximally activating images on TinyCLIP, which gives a better intuition of how the model hierarchically processes information.

Check out my brief paper liston Vision Transformers and Mechanistic Interpretability for general context.

How to get involved

Use and contribute to the Prisma repo. Check out our open Issues.

Check out our Spring 2024 Roadmap

Community. Join the Prisma Discord.

Collaboration. Work on the Open Problems below.

Post more Open Problems in the comments, or discuss what excites you in particular!

Get mentorship. I would be happy to mentor people on any of the Open Problems above, or a new one that you propose. However, please ensure your proposal is well-thought-out and includes preliminary results on any of the medium to hard problems. Feel free to reach out to me on the LW forum or the Prisma Discord.

Funding for open source alignment and interpretability. As an open-source project, we value the support of our community and sponsors. Open source funding helps us cover expenses and invest in the project’s growth. Feel free to reach out if you’d like to discuss potential funding opportunities!

Open Problems in Vision Mechanistic Interpretability

Here are some Open Problems to get started. If inspired, you are encouraged to post your own in the comments, or comment on the ideas that most grab your attention.

Easy and Exploratory

Explore interpretable neurons in Mindreader:

Pay attention to the neurons that correlate with each other upstream and downstream. For example, this Layer 5 neuron activates strongly for legs and appears to correlate with this upstream Layer 6 foot neuron (originally found by Noah MacCallum).

Play with the attention head JavaScript visualizers to visually inspect attention heads.

Do any heads seem to pick up on the same patterns across images?

Find 1-3 attention heads that appear to capture interesting features.

Generate maximally activating images for a ViT/CLIP. The maximally activating images were used to make the Mindreader. I will provide sample code to identify the maximally activating images for each neuron on request.

Experiment with different models and datasets for finding maximally activating images.

Plot histograms of neuron activations to assess false positives and negatives.

Run the logit lens on various images in the Main Demo notebook.

Are certain ImageNet classes identified earlier in the net than others?

Load in a toy ViT into Prisma and examine the attention heads. Do you notice any invariant attention scores/patterns for certain types of images?

Look at the attention heads of the 3-layer toy ViT.

Find canonical circuit patterns in the 1-4 layer ViTs. (Note these ViTs are patch size 16 whose attention is currently not feasible to render in the JavaScript attention head viewer.)

Expanding Techniques to New Architectures and Datasets

Swap CLIP / Vanilla ViTs. Run the techniques above but swap the architecture.

Run the Main Demo on TinyCLIP instead of a vanilla ViT (which is pretrained only on 1k-ImageNet, instead of TinyCLIP’s image/text).

For the maximally activating images task (Problem 3), use a vanilla ViT instead of TinyCLIP.

Video Vision Transformer. Run the techniques on a video vision transformer, which you can specify in the HookedViTConfig here (thanks Rob Graham for the idea and adapting the model to Prisma).

How do you account for time as a new dimension? How is the model representing time?

Patch-level labels. Use patch-level labels for your dataset.

ImageNet is currently only labeled at the class level. Often, this is too coarse-grained. For example, a man eating a burrito, which is labeled “burrito” for ImageNet, has many components: the man, the burrito, his shirt, and the cutlery on the table. Patch-level labels were created by Rob Graham using SAM on ImageNet Images and give a boolean mask for every object in the image. See our Huggingface link for more details on patch-level labels and the SAM pipeline.

Generating maximally activating images (Problem 3) is a good candidate as a task for patch-level labels, because now your neurons’ labels will be much more fine-grained than merely using ImageNet class-level labels.

Deeper Investigations

Finish off the cat/dog circuit from the Main Demo Notebook.

Run linear probes on the notebook/scratchpad token to the right of the Border Collie. How much cat vs dog information does the patch contain at each layer of the net?

How general is Attention Head 4, Layer 11 (the “Cat-Dog Decider Head”), which appears to be pushing the net’s decision from Border Collie to tabby cat? Does the attention head make the same decision for other images containing both cats and dogs?

What is the full circuit for cats and dogs, according to the rigorous definition of a circuit?

Attention patterns vs attention scores.

In the Interactive Attention Head Tour, the attention scores (pre-softmax) sometimes look more visually interpretable than the attention patterns (post-softmax). How do we connect our observations about the attention scores to our observations about the attention patterns?

Tuned Lens. Use the Tuned Lens instead of the classical logit lens for the Emoji Logit Lens (train a probe for each block). Does the Tuned Lens improve interpretability?

Recreate the “Layer-Level Logit Lens” plots in the Emoji Logit Lens notebook using Tuned Lenses instead of the current vanilla logit lens. Do the results corroborate each other?

Attention Ablations: Change the ViT’s bidirectional attention to unidirectional (like language models). How does this affect segmentation maps and information flow?

Adding registers. Try adding registers as in Darcet et al (2023) and see what happens to the segmentation map.

Superposition. Find superpositioned ViT neurons and disentangle the layer with SAEs

Circuit Identification. Do full circuit identification for simple naturalistic data like MNIST.

Disentanglement datasets. Run the disentanglement dataset dSprites through the model. Does the internal representation of the net show disentanglement? We have some pre-trained dSprites transformers by Yash Vadi here.

Are there induction heads in vision?

Induction heads emerge with two or more layers in language. Is there an analog in vision (or the emergence of some other useful symmetry)?

The symmetries may depend a lot on loss function (e.g. masked autoencoder losens may yield different symmetries than classification loss, although this is an open question).

Vision attention is bidirectional, so it’s less obvious what “induction” means here. The canonical definition from language breaks down.

Reverse engineer textual inversion—Add a new, made-up word to the CLIP text encoder and fine-tune with 4-6 corresponding images (e.g. you can finetune the model to label your face with your name). How do the model’s internals change?

Advanced Investigations

Vision training dynamics and phase transitions.

Detect canonical phase transitions in ViT training loss curves (analogous to induction head loss bumps).

Praneet Suresh found that reconstruction loss, and visualizing the reconstructed image throughout training, is a convenient way to detect phase transitions.

Compare the interpretability of CLIP vs a vanilla ViT.

There is an unproven intuition that CLIP is more interpretable than a vanilla ViT. CLIP has better labels than a vanilla ViT. CLIP co-optimized with captions, which are more granular labels. For example, “the tabby cat sat on the window” (a CLIP-style label) is more precise than the plain ImageNet class “tabby cat.” The higher-quality labels may result in “better-factored” internal representations.

How interpretable is a ViT in comparison to CLIP? You explore this question by checking maximally activating images on both models, and running the Logit Lens notebook on TinyCLIP instead of a ViT. Brainstorm your own techniques to compare the internal representations of the models.

Patch information.

How does local information in spatial patches propagate to the global CLS token? Could we get a circuit-level breakdown?

Why do the patches in the upper layer of CLIP store global information? How are they computed from local patches?

Reverse-Engineering Vision Transformer Registers

Vision transformer registers (Darcet et. al (2023)) were a recent phenomenon in the vision community where adding blank tokens dramatically improved the attention maps of a ViT

On a low-level, mechanistic basis, how does local information from patch tokens propagate to the global tokens, including the CLS token?

Try removing a few register tokens, see what breaks. Are there heads that are specialized to attend to register tokens?

Train an SAE on register tokens and see if you can disentangle what they store. Also run linear probes on register tokens.

Visual reasoning. Use a dataset like CLEVR to see if CLIP does visual reasoning. Does CLIP have visual reasoning “circuits”? Note: CLIP may be bad at CLEVR, which is a complex dataset. Try creating your own simpler visual reasoning tasks (e.g. 2 apples + 2 apples = 4 apples), as a baseline.

Create an open source dataset with very simple reasoning tasks for this purpose. This would be a service to the broader research community!

Replicate the results of Gandelsman et al. Do you notice attention heads specializing for certain semantic groups?

Other architectures

Explore models like Flamingo.

Lay groundwork to analyze diffusion models.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to this most excellent mosaic of communities.

Thank you to Praneet Suresh, Rob Graham, and Yash Vadi, and the other core contributors to the Prisma Repo. Thank you to my PI, Blake Richards, and the rest of our lab at Mila for their support and feedback.

Thank you to Neel Nanda for guidance in bringing mechanistic interpretability to another modality, to Joseph Bloom for your advice on building a repo, to Arthur Conmy for coining the term “dogit lens,” and to the rest of the MATS community for your feedback.

Thank you to the Prisma group at Mila for your feedback, including Santoshi Ravichandran, Ali Kuwajerwala, Mats L. Richter, and Luca Scimeca; members of LiNCLab, including Arna Ghosh and Dan Levenstein; and members of CERC-AAI lab, including Irina Rish and Ethan Caballero. Thank you to Karolis Ramanauskas, Noah MacCallum, Rob Graham, and Romeo Valentin for your feedback on the tutorial notebooks.

Finally, thank you to the South Park Commons community for your support, including Ker Lee Yap, Abhay Kashyap, Jonathan Brebner, and Ruchi Sanghvi and Aditya Agarwal.

This research was generously supported by Blake Richards’s lab, which was funded by the Bank of Montreal; NSERC (Discovery Grant: RGPIN-2020-05105; Discovery Accelerator Supplement: RGPAS-2020-00031; Arthur B. McDonald Fellowship: 566355-2022); CIFAR (Canada AI Chair; Learning in Machine and Brains Fellowship); and a Canada Excellence Research Chair Award to Prof. Irina Rish; and by South Park Commons. This research was enabled in part by support provided by Calcul Québec and the Digital Research Alliance of Canada. We acknowledge the material support of NVIDIA in the form of computational resources.

I think working on mechanistic intepretability in a variety of domains, architectures, and modalities seems like a reasonable research diversification bet.

However, it feels pretty odd to me to describe branching out into other modalities as crucial when we haven’t yet really done anything useful with mechanistic interpretability in any domain or for any task.

You say:

And on X/twitter:

But, I feel like the situation is relatively analogous to:

Like yeah, you’ll eventually need to handle non-language modalities and you should probably sanity check that they aren’t key additional blockers with the methodology, but also why would there be key methodologies that mean it can solve our problems in the language case but note the vision/multimodal case? And the main obstacle is demonstrating basic technical feasibility, not branching out?

Again, I’d like to stress that studying a variety of cases with mech interp seems like a reasonable research diversification bet.

(And I don’t want to be the language police here, just pushing back a bit on the implicit vibes.)

There is another argument that could be made for working on other modalities now: there could be insights which generalize across modalities, but which are easier to discover when working on some modalities vs. others.

I’ve actually been thinking, for a while now, that people should do more image model interprebility for this sort of reason. I never got around to posting this opinion, but FWIW it is the main reason I’m personally excited by the sort of work reported here. (I have mostly been thinking about generative or autoencoding image models here, rather than classifiers, but the OP says they’re building toward that.)

Why would we expect there to be transferable insights that are easier to discover in visual domains than textual domains? I have two thoughts in mind:

First thought:

The tradeoff curve between “model does something impressive/useful that we want to understand” and “model is conveniently small/simple/etc.” looks more appealing in the image domain.

Most obviously: if you pick a generative image model and an LLM which do “comparably impressive” things in their respective domains, the image model is going to be way smaller (cf.). So there are, in a very literal way, fewer things we have to interpret—and a smaller gap between the smallest toy models we can make and the impressive models which are our holy grails.

Like, Stable Diffusion is definitely not a toy model, and does lots of humanlike things very well. Yet it’s pretty tiny by LLM standards. Moreover, the SD autoencoder is really tiny, and yet it would be a huge deal if we could come to understand it pretty well.

Beyond mere parameter count, image models have another advantage, which is the relative ease of constructing non-toy input data for which we know the optimal output. For example, this is true of:

Image autoencoders (for obvious reasons).

“Coordinate-based MLP” models (like NeRFs) that encode specific objects/scenes in their weights. We can construct arbitrarily complex objects/scenes using 3D modeling software, train neural nets on renders of them, and easily check the ground-truth output for any input by just inspecting our 3D model at the input coordinates.

By contrast, in language modeling and classification, we really have no idea what the optimal logits are. So we are limited to making coarse qualitative judgments of logit effects (“it makes this token more likely, which makes sense”), ignoring the important fine-grained quantitative stuff that the model is doing.

None of that is intrinsically about the image domain, I suppose; for instance, one can make text autoencoders too (and people do). But in the image domain, these nice properties come for free with some of the “real” / impressive models we ultimately want to interpret. We don’t have to compromise on the realism/relevance of the models we choose for ease of interpretation; sometimes the realistic/relevant models are already convenient for interpretability, as a happy accident. The capabilities people just make them that way, for their own reasons.

The hope, I guess, is that if we came pretty close to “fully understanding” one of these more convenient models, we’d learn a lot of stuff a long the way about how to interpret models in general, and that would transfer back to the language domain. Stuff like “we don’t know what the logits should be” would no longer be a blocker to making progress on other fronts, even if we do eventually have to surmount that challenge to interpret LLMs. (If we had a much better understanding of everything else, a challenge like that might be more tractable in isolation.)

Second thought:

I have a hunch that the apparent intuitive transparency of language (and tasks expressed in language) might be holding back LLM interpretability.

If we force ourselves to do interpretability in a domain which doesn’t have so much pre-existing taxonomical/terminological baggage—a domain where we no longer feel it’s intuitively clear what the “right” concepts are, or even what any breakdown into concepts could look like—we may learn useful lessons about how to make sense of LLMs when they aren’t “merely” breaking language and the world down into conceptual blocks we find familiar and immediately legible.

When I say that “apparent intuitive transparency” affects LLM interpretability work, I’m thinking of choices like:

In circuit work, researchers select a familiar concept from a pre-existing human “map” of language / the world, and then try to find a circuit for it.

For example, we ask “what’s the circuit for indirect object identification?”, not “what’s the circuit for frobnoloid identification?”—where “a frobnoloid” is some hypothetical type-of-thing we don’t have a standard term for, but which LMs identify because it’s useful for language modeling.

(To be clear, this is not a critique of the IOI work, I’m just talking about a limit to how far this kind of work can go in the long view.)

In SAE work, researchers try to identify “interpretable features.”

It’s not clear to me what exactly we mean by “interpretable” here, but being part of a pre-existing “map” (as above) seems to be a large part of the idea.

“Frobnoloid”-type features that have recognizable patterns, but are weird and unfamiliar, are “less interpretable” under prevailing use of the term, I think.

In both of these lines of work, there’s a temptation to try to parse out the LLM computation into operations on parts we already have names for—and, in cases where this doesn’t work, to chalk it up either to our methods failing, or to the LLM doing something “bizarre” or “inhuman” or “heuristic / unsystematic.”

But I expect that much of what LLMs do will not be parseable in this way. I expect that the edge that LLMs have over pre-DL AI is not just about more accurate extractors for familiar, “interpretable” features; it’s about inventing a decomposition of language/reality into features that is richer, better than anything humans have come up with. Such a decomposition will contain lots of valuable-but-unfamiliar “frobnoloid”-type stuff, and we’ll have to cope with it.

To loop back to images: relative to text, with images we have very little in the way of pre-conceived ideas about how the domain should be broken down conceptually.

Like, what even is an “interpretable image feature”?

Maybe this question has some obvious answers when we’re talking about image classifiers, where we expect features related to the (familiar-by-design) class taxonomy—cf. the “floppy ear detectors” and so forth in the original Circuits work.

But once we move to generative / autoencoding / etc. models, we have a relative dearth of pre-conceived concepts. Insofar as these models are doing tasks that humans also do, they are doing tasks which humans have not extensively “theorized” and parsed into concept taxonomies, unlike language and math/code and so on. Some of this conceptual work has been done by visual artists, or photographers, or lighting experts, or scientists who study the visual system … but those separate expert vocabularies don’t live on any single familiar map, and I expect that they cover relatively little of the full territory.

When I prompt a generative image model, and inspect the results, I become immediately aware of a large gap between the amount of structure I recognize and the amount of structure I have names for. I find myself wanting to say, over and over, “ooh, it knows how to do that, and that!”—while knowing that, if someone were to ask, I would not be able to spell out what I mean by each of these “that”s.

Maybe I am just showing my own ignorance of art, and optics, and so forth, here; maybe a person with the right background would look at the “features” I notice in these images, and find them as familiar and easy to name as the standout interpretable features from a recent LM SAE. But I doubt that’s the whole of the story. I think image tasks really do involve a larger fraction of nameless-but-useful, frobnoloid-style concepts. And the sooner we learn how to deal with those concepts—as represented and used within NNs—the better.

Thanks for your comment. Some follow-up thoughts, especially regarding your second point:

There is sometimes an implicit zeitgeist in the mech interp community that other modalities will simply be an extension or subcase of language.

I want to flip the frame, and consider the case where other modalities may actually be a more general case for mech interp than language. As a loose analogy, the relationship between language mech interp and multimodal mech interp may be like the relationship between algebra and abstract algebra. I have two points here.

Alien modalities and alien world models

The reason that I’m personally so excited by non-language mech interp is due to the philosophy of language (Chomsky/Wittgenstein). I’ve been having similar intuitions to your second point. Language is an abstraction layer on top of perception. It is largely optimized by culture, social norms, and language games. Modern English is not the only way to discretize reality, but the way our current culture happens to discretize reality.

To present my point in a more sci-fi way, non-language mech interp may be more general because now we must develop machinery to deal with alien modalities. And I suspect many of these AI models will have very alien world models! Looking at the animal world, animals communicate with all sorts of modalities like bees seeing with ultraviolet light, turtles navigating with magnet fields, birds predicting weather changes with barometric pressure sensing, aquatic animals sensing dissolved gases in the water, etc. Various AGIs may have sensors to take in all sorts of “alien” data that the human language may not be equipped for. I am imagining a scenario in which a superintelligence discretizes the world in seemingly arbitrary ways, or maybe following a hidden logic based on its objective function.

Language is already optimized by humans to modularize reality into this nice clean way. Perception already filtered through language is by definition human interpretable so the deck is already largely stacked in our favor. You allude to this with your point photographers, dancers, etc developing their own language to describe subtle patterns in perception that the average human does not have language for. Wine connoisseurs develop vocabulary to discretize complex wine-tasting percepts into words like “bouquet” and “mouth-feel.” Make-up artists coin new vocabulary for around contouring, highlighting, cutting the crease, etc to describe subtle artistry that may be imperceptible to the average human.

I can imagine a hypothetical sci-fi scenario where the only jobs available are apprenticing yourself to a foundation model at a young age for life, deeply understanding its world model, and communicating its unique and alien world model to the very human realm of your local community (maybe through developing jargon or dialect, or even through some kind of art, like poetry, or dance, communication forms humans currently use to bypass the limitations of language).

Self-supervised vision models like DINO are free of a lot of human biases but may not have as interpretable of a world model as CLIP, which is co-optimized with language. I believe DINO’s lack of language bias to be either a safety issue or a superpower, depending on the context (safety in that we may not understand this “alien” world model, but superpower in that DINO may be freer from human biases that may be, in many contexts, unwanted!).

As a toy example, in this post, the above vision transformer classifies the children paying with the lion as “abaya.” This is an ethnically biased classification, but the ViT only has 1k ImageNet concepts. The limits of its dictionary are quite literally the limits of its world (in a Wittgenstein sense)! But there are so many other concepts we can create to describe the image!

Text-perception manifolds

Earlier, I mentioned that English is currently the way our culture happens to discretize reality, and there may be other coherent ways to discretize the same reality.

Consider the scene of a fruit bowl on a table. You can start asking questions such as, How many ways are there to carve up this scene into language? How many ways can we describe this fruit bowl in English? In all human languages, including languages that don’t have the concepts of fruit or bowls? In all possible languages? (which takes us to Chomsky). These question have a real analysis flavor to them, in that you’re mapping continuous perception to discrete language (yes, perception is represented discretely on a computer, but there may be advantages to framing this in a continuous way). This manifold may be very useful in navigating alignment problems.

For example, there was a certain diffusion model that would always generate salads in conjunction with women due to the spurious correlation. One question I’m deeply interested in: is there a way to represent the model’s text-to-perception world model as a manifold, and then modify it? Can you then modify this manifold to decorrelate women and salad?

A text-image manifold formalization could further answer useful questions about granularity. For example, consider a man holding an object, where object can map to anything from a teddy bear to a gun. By representing the mapping between the text/semantics of the word “object” and the perceptual space of teddy bears, guns, and other pixel blobs that humans might label as objects as a manifold, we could capture the model’s language-to-perception world model in a formal mathematical structure.

—

The above two points are currently just intuitions pending formalization. I have a draft post on why I’m so drawn to non-language interp for these reasons, which I can share soon.

Noted, and thank you for flagging. I mostly agree, and do not have much to add (as we seem mostly in agreement that diverse, bluesky research is good), other than this may shape the way I present this project going forward.

I think the objective of interpretability research is to demystify the mechanisms of AI models, and not pushing the boundaries in terms of achieving tangible results / state of the art performance (I do think that interpretability research indirectly contributes in pushing the boundaries as well, because we’d design better architectures, and train the models in a better way as we understand them better). I see it being very crucial, especially as we delve into models with emergent abilities. For instance, the phenomenon of in-context learning by language models used to be considered a black box, now it has been explained through interpretability efforts. This progress is not trivial; it lays the groundwork for safer and more aligned AI systems by ensuring we have a clearer grasp of how these models make decisions and adapt.

I also think there are key differences in how these architectures function across modalities, such as attention being causal for language, while being bidirectional for vision, and how even though tokens and image patches are analogous, they are consumed and processed differently, and so much more. These subtle differences change how the models operate across modalities even though the underlying architecture is the same, and this is exactly what necessitates the mech interp efforts across modalities.

Has it? I’m quite skeptical. (Separately, only a small fraction of the efforts you’re talking about are well described as mech interp or would require tools like these.)

I don’t really want to get into this, just registering my skeptism. I’m quite familiar with the in-context learning and induction heads work assuming that’s what you’re refering to.

+1 that I’m still fairly confused about in context learning, induction heads seem like a big part of the story but we’re still confused about those too!

I agree that in-context learning is not entirely explainable yet, but we’re not completely in the dark about it. We have some understanding and direction or explainability regarding where this ability might stem from, and it’s only going to get much clearer from here.

Insofar as the objective of intepretability research was to do something useful (e.g. detect misalignment or remove it in extremely powerful future AI systems), I think it should also aim to be useful for solving some problems that feel roughly analogous now. Most useful things can be empirical demonstrated to accomplish specific things better than existing methods, at least in test beds.

(Noteably, I think things well described as “interpretability” often pass this bar, but I think “mech interp” basically never does. I’m using the definition of mech interp from here.)

To be clear, it’s fine if mech interp isn’t there yet. Many things haven’t demonstrated any clear useful applications and can still be worth investing in.

For more discussion see here.

Exciting stuff, thanks!

It’s a little surprising to me how bad the logit lens is for earlier layers.

It was surprising to me too. It is possible that the layers do not have aligned basis vectors. That’s why corroborating the results with a TunedLens is a smart next step, as they currently may be misleading.

I greatly appreciated the time invested in coding the interactive demos, they help clarifying the insights into the underlying concepts – it reminds me of Colah’s posts.

Questions:

Are you going to release tools for the interpretation of other models?

How might one visualize other modalities? like audio or web actions?

Have you considered developing a generalized interpretability framework that could scale these techniques across different architectures and modalities? A unified “interpretability platform” could help broaden access and grow a dedicated community around your work.

Right now, there’s a lot to exploit with CLIP and ViTs so that will be the focus for awhile. We may expand to Flamingo or other models if there is demand.

Other modalities would be fascinating. I imagine they have their own idiosyncrasies. I would be interested in audio in the future but not at the expense of first exploiting vision.

Ideally, yes; a unified interp framework for any modality is the north star. I do think this will be a community effort. Research in language built off findings from many different groups and institutions. Vision and other modalities are currently just not in the same place.