(Appetitive, Consummatory) ≈ (RL, reflex)

“Appetitive” and “Consummatory” are terms used in the animal behavior literature. I was was briefly confused when I first came across these terms (a year or two ago), because I’m most comfortable thinking in terms of brain algorithms, whereas these terms were about categories of behavior, and the papers I was reading didn’t spell out how the one is related to the other.

I’m somewhat embarrassed to write this because the thesis seems so extremely obvious to me now, and it’s probably obvious to many other people too. So if you read the title of this post and were thinking “yeah duh”, then you already get it, and you can stop reading.

Definition of “appetitive” and “consummatory”

In animal behavior there’s a distinction between “appetitive behaviors” and “consummatory behaviors”. Here’s a nice description from Hansen et al. 1991 (formatting added, references omitted):

It is sometimes helpful to break down complex behavioral sequences into appetitive and consummatory phases, although the distinction between them is not always absolute.

Appetitive behaviors involve approach to the appropriate goal object and prepare the animal for consummatory contact with it. They are usually described by consequence rather than by physical description, because the movements involved are complex and diverse.

Consummatory responses, on the other hand, depend on the outcome of the appetitive phase. They appear motorically rigid and stereotyped and are thus more amenable to physical description. In addition, consummatory responses are typically activated by a more circumscribed set of specific stimuli.

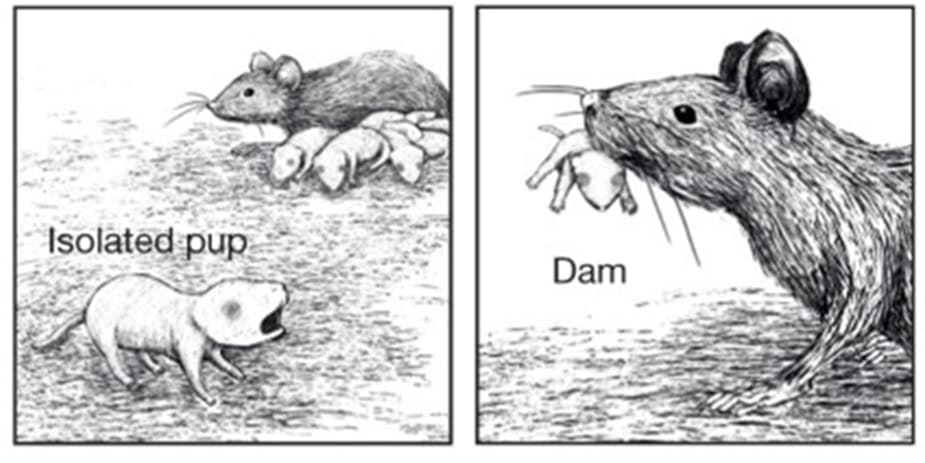

So for example, rat mothers have a pup retrieval behavior; if you pick up a pup and place it outside the nest, the mother will walk to it, pick it up in her mouth, and bring it back to the nest.

The walking-over-to-the-pup aspect of pup-retrieval is clearly appetitive. It’s not rigid and stereotyped; for example, if you put up a trivial barrier between the rat mother and her pup, the mother will flexibly climb over or walk around the barrier to get to the pup.

Whereas the next stage (picking up the pup) might be consummatory (I’m not sure). For example, if the mother always picks up the pup in the same way, and if this behavior is innate, and if she won’t flexibly adapt in cases where the normal method for pup-picking-up doesn’t work, then all that would be a strong indication that pup-picking-up is indeed consummatory.

Other examples of consummatory behavior: aggressively bristling and squeaking at an unwelcome intruder, or chewing and swallowing food.

How do “appetitive” & “consummatory” relate to brain algorithms?

Anyway, here’s the “obvious” point I want to make. (It’s a bit oversimplified; caveats to follow.)

Appetitive behaviors are implemented via an animal’s reinforcement learning (RL) system. In other words, the animal has experienced reward / positive reinforcement signals when a thing has happened in the past, so they take actions and make plans so as to make a similar thing happen again in the future. RL enables flexible, adaptable, and goal-oriented behaviors, like climbing over an obstacle in order to get to food.

Consummatory behaviors are generally implemented via the triggering of specific innate motor programs stored in the brainstem. For example, vomiting isn’t a behavior where the end-result is self-motivating, and therefore you systematically figure out from experience how to vomit, in detail, i.e. which muscles you should contract in which order. That’s absurd! Rather, we all know that vomiting is an innate motor program. Ditto for goosebumps, swallowing, crying, laughing, various facial expressions, orienting to unexpected sounds, flinching, and many more.

There are many situations / behaviors in which an essential role is played by both the RL system and the triggering of specific innate motor programs stored in the brainstem. In these cases, they’re neither appetitive nor consummatory. Or I guess maybe both? Well at any rate, the distinction stops being useful. For example, rats have sex in a very specific way, highly “amenable to physical description” (e.g. “lordosis behavior”). That’s consummatory. Whereas human sexual intercourse (or bonobo sexual intercourse), in all its endless variety, doesn’t really fit neatly into either the “appetitive” or “consummatory” bucket.

Caveats

The above isn’t 100% reliable, because the terms “appetitive” and “consummatory” are used to talk about the behavior rather than how it’s implemented in the brain, and the relationship is not always straightforward. In particular:

There are situations where the RL system can by itself lead to a behavior that appears “motorically rigid and stereotyped”, and hence might be described in the literature as consummatory: namely, if there’s really just one “best” way to accomplish an immediate goal, and this way is readily and universally learned by all rats (via RL) very early in life.

If there’s an innate motor program to do some particular thing X (e.g. sneeze), the RL system can still obviously be involved in making the animal “choose” to initiate behavior X. In this case, the detailed implementation of X (which muscles to contract in which order, etc.) would be unrelated to RL, but the time and location where the animal “presses the X button”, so to speak, would be related to RL.

Example of a time when this came up for me: the MPOA→VTA pathway in parental behavior

Last year I was chatting with Mateusz Baginski in relation to his Neurological basis of parental care writeup that he did at AI Safety Camp. Rodent parental care involves various little cell groups in the medial preoptic nucleus (MPOA) of the hypothalamus. Those cell groups send signals to VTA (which is centrally and directly involved in RL), and they also send signals to other areas of the hypothalamus and brainstem (which are not).

Anyway, Mateusz claimed that the MPOA→VTA connections in particular were essential for appetitive, but not consummatory, rodent parental behaviors. What I actually said to him was something like: “Huh, really? Are you sure? What’s the experimental evidence for that?” (And he had a great answer.) But what I should have said was: “OK cool, that’s perfectly in line with what any reasonable person would have guessed a priori.”

Lordosis or snow speeder attack? You be the judge...

https://preview.redd.it/9uvsq2hakepy.jpg?auto=webp&s=e4463be21049ed72ca76d4abfb44f983cccdd31f