Ranked Choice Voting is Arbitrarily Bad

Cross posting from https://applieddivinitystudies.com/2020/09/02/ranked-bad/

Recently, there’s been headway in adopting Ranked-Choice Voting, used by several states in the 2020 US Democratic presidential primaries and to be adopted by New York City in 2021.

For all its virtues, Ranked Choice Voting contains a number of risks, largely due to tactical voting and democratic illegitimacy.

First, a quick primer on existing systems.

The one we’re used to is called Plurality Voting, and is by far the simplest: Each voter casts a vote for one candidate, and the candidate with the most votes wins.

Though clear and intuitive, there are several problems best illustrated by example:

Tactical Voting for “Realistic Candidates” Say public polls report:

45% of voters prefer Alice

45% of voters prefer Bob

10% of voters prefer Carol

No matter how strongly voters support Carol, on election day, they would rather vote for Alice or Bob than “waste” a vote on a candidate who won’t win.

It’s worth asking why Carol was polling so low in the first place, but a common explanation is perpetuation through a party system. If Alice and Bob’s parties have won historically, the electorate may be locked into a perpetual two-party system, no matter how compelling a particular third-party candidate happens to be.

Loss of Popular Moderate Candidates In another race, voters have real preferences such that:

50% of voters prefer Alice > Carol > Dave > Bob

50% of voters prefer Bob > Carol > Dave > Alice

Alice and Bob are both despised by half the population, yet one of them is guaranteed to win. Meanwhile, Carol has universal appeal, but would receive 0 votes in a plurality election, no matter how polarizing the other candidates are.

In a more extreme case, we might have:

25% of voters prefer Alice > Bob > Carol > Dave

25% of voters prefer Bob > Alice > Carol > Dave

30% of voters prefer Dave > Alice > Carol > Bob

20% of voters prefer Carol > Alice > Bob > Dave

Alice is the clear intuitive choice, but according to plurality rules, Dave ends up winning despite being despised by 70% of the electorate.

Tactics in Ranked Choice Voting In theory, these are precisely the problems solved by RCV, but the general form I’ve outlined above can still apply.

Given real preferences:

33% of voters prefer Alice > Bob > Dave > Carol

33% of voters prefer Bob > Alice > Dave > Carol

34% of voters prefer Dave > Alice > Bob > Carol

Each cohort knows that Carol is not a realistic threat to their preferred candidate, and will thus rank her second, while ranking their true second choice last. For any individual, this is a good strategy to maximizing the odds of their preferred candidate, but in aggregate, it leads to:

33% of voters prefer Alice > Carol > Bob > Dave

33% of voters prefer Bob > Carol > Dave > Alice

33% of voters prefer Dave > Carol > Alice > Bob

Leading to a victory for Carol, even though she was universally despised.

What’s Wrong with Tactics? At some point, we might bite the bullet and say that all voting is tactical, in the sense that it incorporates outside information rather than merely expressing one’s preferences.

But as we saw in the last case, tactical voting doesn’t just skew results, it can have arbitrarily bad outcomes, like the election of a universally despised candidate, or the failure to elect a universally liked candidate.

Self-defeating Tactics Over Time It is also worth introducing the concept of self-fulfilling and self-defeating tactics.

Self-fulfilling manipulation is what we’re used to. A candidate attempts to portray themselves as having a real chance of winning that is not yet guaranteed, thus giving voters the impression that their vote is likely to matter.

Self-defeating manipulation is weirder, and possibly much worse. Take our RCV scenarios again with equally sized cohorts:

Cohort 1 prefers: Alice > Bob > Carol

Cohort 2 prefers Bob > Alice > Carol

2 weeks before the election, a polling organization correctly reports these preferences, thus creating the perverse reaction described earlier, and a shift to:

Cohort 1 states a preference for Alice > Carol > Bob

Cohort 2 states a preference for Bob > Carol > Alice

1 week before the election, the polling organization reports these new stated preferences. Voters see that their preferred candidate is no longer at risk of losing to their second favorite, and shifts back to to their real preferences:

Cohort 1 prefers: Alice > Bob > Carol

Cohort 2 prefers Bob > Alice > Carol

Thus restarting the cycle of polling > new tactics > new polling up until election day.

At this point, each voter is confused and uncertain, and votes according to tactical necessity rather than actual preferences. In this scenario, Alice, Bob or Carol could win, and it just depends on the particular rhythm of polling, speed of reporting, date of the election, and other factors largely incidental to voter preferences.

Condorcet Paradox of Circular Preferences Finally, consider the case where ranked choice voting is simply incoherent:

33% of voters prefer Alice > Bob > Carol

33% of voters prefer Bob > Carol > Alice

33% of voters prefer Carol > Alice > Bob

No matter which candidate is elected, there is an alternative preferred by 66% of the population, such that there appears to be no stable solution. If Alice is elected, the majority of voters would prefer that Carol be elected instead.

Note that this is not a coincidental feature of perfectly balanced distributions, we can just as easily have:

Cohort 1 (20%) prefers Alice > Bob > Carol

Cohort 2 (35%) prefers Bob > Carol > Alice

Cohort 3 (45%) prefers Carol > Alice > Bob

Where in the best case scenario, Carol wins, but 55% of voters would prefer Bob.

(In general, the worst case scenario depends on the number of candidates, such that in a 5 candidate race, an alternative could be prefered by up to 80% of voters.)

One might object that this is simply unrealistic. Are such circular preferences coherent?

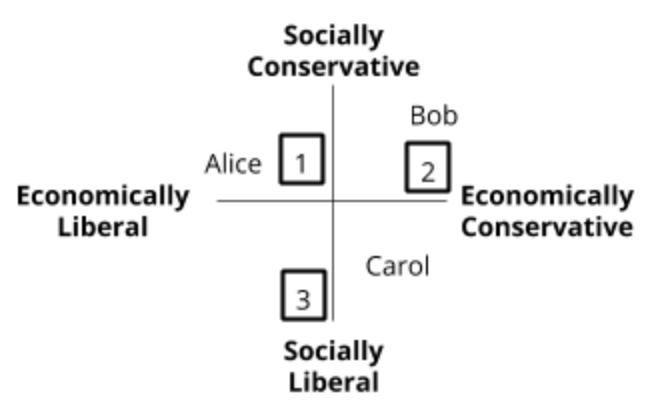

We can generate intuition using a simple model where candidates and voters are mapped on 2-dimensional space, and rank candidates based on proximity. In the above example:

The key thing to note is that circularity exists across cohorts, but not within them. Each voter or cohort has a simple linear ranked order, it is only in aggregate that the paradox appears.

To be clear, this paradox exists equally in Plurality Voting, it just remains invisible. Even without stated preferences, real preferences could contain the same circular result.

But since voting serves as a coordination mechanism, this invisibility is a feature. With a single vote per person, simple plurality feels like a fair result. In contrast, Ranked Voice Voting risks the instability of a majority-preferred alternative, and undermines democratic legitimacy.

In the Australian system (which is the one I’m familiar with) Carol would lose this election. She has the fewest (in this case 0) first-preference votes, so she is the first candidate eliminated.

Yeah, I think ranked-choice voting almost always refers to [instant-runoff voting](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Instant-runoff_voting), which would indeed eliminate Carol first here. So I think the post is just wrong with that example.

A real example of a questionable RCV outcome was the [2009 Burlington, VT mayoral election](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Instant-runoff_voting#2009_Burlington_mayoral_election), where the Democrat would have beaten either the Progressive or the Republican head-to-head but had fewer first-choice votes than either, leading to a Progressive victory over the Republican in the final round. This seems bad but not arbitrarily bad—the winner wasn’t universally despised or anything.

Huh? This doesn’t make sense. In which voting system would that help? In most systems that would make no difference to the relative probability of your first and second choices winning.

This is called burying. It makes sense in systems that violate the later-no-help or later-no-harm criteria, but instant-runoff voting satisfies both of those.

https://electowiki.org/wiki/Tactical_voting#Burying

As others have pointed out, the ranked voting method implemented in the US is instant runoff voting, which generally isn’t vulnerable to burying and thus doesn’t suffer from the DH3 pathology (the scenario where a universally disliked candidate wins due to tactical voting).

The author doesn’t make it clear which method they based their examples on, but they would be most applicable to the Borda count. That being said, since they refer to “the case where ranked choice voting is simply incoherent”, I’m guessing they used a Condorcet method with no fallback rule.

… except that you have her winning the election, which means that she obviously is a realistic threat, which means you don’t want to vote for her. Why wouldn’t the voters all assume that everybody else was going to do the same thing they were, thus making Carol a danger?

I don’t see why you’d say that. People are always complaining about it, and strategies for it are well known and constantly discussed every time an election comes around.

Personally I like range voting, though.

I also think that the example isn’t perfect (although I haven’t formalized why yet). But, you’re describing tactical voting, which is considered one of the “downsides” of RCV.

You’re already being tactical when you decide that Carol isn’t a threat and (falsely) uprank her. What changes if you go a step further to decide that she is a threat?

In fact, I think that the standard formalism for defining “tactical voting” is in terms of submitting a vote that doesn’t faitfully reflect your true preferences. Under that formalism, falsely upranking Carol is tactical, but switching back to your true preferences because of what you expect others to do actually isn’t tactical.

… and it’s odd to talk about tactical voting as a “downside” of one system or another, since there’s a theorem that says tactical voting opportunities will exist in any voting system choosing between more than two alternatives: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gibbard–Satterthwaite_theorem . At best you can argue about which system has the worst case of the disease.

And, if you’re comparing the two, plurality has a pretty bad case of tactical vulnerability, probably worse than IRV/RCV. That’s why people want to change it: because tactical voting under plurality entrenches two-party systems.

I would personally greatly prefer you use the name “instant runoff” rather than “ranked choice”.

“instant runoff” is descriptive of what it’s actually doing, if the listener is familiar with runoff elections.

There are many other voting methods which rank choices. Calling it “ranked choice” seems to marginalize this entire category of voting methods. For example, Borda count is a much older voting method which ranks choices.

This isn’t just my opinion; I was convinced by Jameson Quinn:

Would you be willing to edit the article to change the term?

Sorry for focusing on nitpicks, but: I generally prefer writers taboo phrases like “clear intuitive choice” for voting theory. I have few intuitions when I look at a set of ordinal preferences like this! It seems like voting theorists do have such intuitions, and tend to heavily assume their readers do, too. My working hypothesis is that any time voting theorists invoke the concept of “intuitive winner” in an election, they actually could (with sufficient introspection) name a specific property which this “intuitive winner” has, and could argue for the appeal of this property. This would better communicate the intuition to the rest of us, and potentially, clarify arguments and positions for the voting theorist as well.

As others have pointed out, this does not seem true. I believed you for a few days but then noticed my confusion when I tried to explain it to someone else. I have downvoted the post as a result of this severe error, but would upvote it again if corrected.

What analysis has been done regarding tactical poll responses? For example, in a two-party FPTP election, isn’t there an incentive to claim to support your less-prefered candidate in order to motivate your preferred candidate’s supporters and make the other’s complacent?