There are two nuclear options for treating depression: Ketamine and TMS; This post is about the latter.

TMS stands for Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation. Basically, it fixes depression via magnets, which is about the second or third most magical things that magnets can do.

I don’t know a whole lot about the neuroscience—this post isn’t about the how or the why. It’s from the perspective of a patient, and it’s about the what.

What is it like to get TMS?

TMS

The Gatekeeping

For Reasons™, doctors like to gatekeep access to treatments, and TMS is no different. To be eligible, you generally have to have tried multiple antidepressants for several years and had them not work or stop working. Keep in mind that, while safe, most antidepressants involve altering your brain chemistry and do have side effects.

Since TMS is non-invasive, doesn’t involve any drugs, and has basically little to no risk or side effects, doctors want to make sure that you’ve tried everything else first.

(I suppose if the American healthcare system made sense, a lot of people would be out of the job.)

In any case, when I applied for the treatment (after talking to my psychiatrist about it), I went to a clinic that does the treatment, and in the first appointment went through the standard rigmarole with insurance information and medical history. In order to be eligible, I had to complete a form indicating my history with antidepressants (I’ve tried several), and some other surveys to indicate how depressed I was (very).

After being informed I was a good candidate for the treatment, I scheduled an initial session with a doctor, which would include a motor threshold test.

Motor Threshold Test

Given that the entire treatment revolves around stimulating one’s brain with a magnetic field, the question comes up: how do they know what region of the brain to stimulate, and where it is in your skull? Also, how do they know how powerful to make the magnetic field?

The answer does not involve an MRI, even though that is also a medical procedure involving magnets that go click.

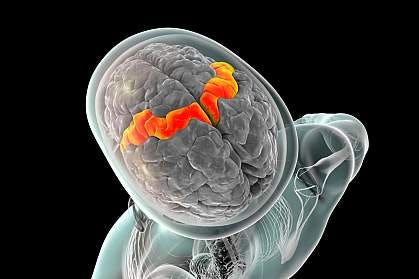

Instead, they do something called a Motor Threshold Test. Basically, there’s a band of the brain responsible for motor function:

The magnetic coil in the TMS machine is placed next to your head along this motor function area:

And then they activate the machine, zapping your brain. Because specific areas of this band are responsible for specific motor functions, they move the machine around until they find the band (they’ll know they found it when you start twitching when they zap you). It’s a strange feeling, a little like having your reflexes tested at the doctor’s: an external stimulus is applied to you, and your body moves involuntarily in response.

Once the motor function area is found, the machine is moved along it until a magnetic pulse causes a very slight—but visible—twitch in your hand. (Since I was getting TMS on the left side of my brain, the twitch was in my right hand; had I gotten TMS on the right side of my brain, the twitch would have been on my left. As far as I’ve been told, left-TMS is for depression, right-TMS is for anxiety. Why that’s the case, I have no idea.)

Locating that point allows the doctor to calibrate the machine, both in location and magnetic field strength, and then they move it a set distance away from that point to reach the area that will be stimulated for the treatment.

I wound up doing two Motor Threshold Tests, once at the beginning and another halfway through (this is an ordinary, scheduled adjustment). After the second the doctor increased the strength of the magnetic field by about 10%.

The Treatment

The treatment itself is straightforward but onerous.

The Schedule

My TMS treatment consisted of 36 treatments, scheduled once a day, five days a week, for seven weeks. I was told that sometimes the last few treatments are spread out a bit more, but the doctor didn’t recommend that for me.

The first 25 treatments were 18 minutes long; the latter 10 treatments 25 minutes long (plus the time to get you set up in the chair and whatnot). Apparently you can veto the extra treatment length if you want, but given that you’re already in the chair I didn’t see a reason to.

In summary, every weekday for almost two months I had to drive to the TMS office, get set up in the chair, receive the treatment, and then drive home (or to work, or wherever). All told it was about an hour a day, five days a week, for seven weeks. Which was kind of a big ask for someone who’s already depressed and having trouble doing anything.

I found myself glad that I didn’t really think through just how big of a commitment it was before I started, because I might not have had the motivation to start if I’d known what I was getting into.

The Experience

I go in to the office, one of the technicians comes and gets me, and we go into a small room containing The Chair. It’s pretty similar to a dentist’s chair, and I’ll sit down and scoot around while the technicians lines up some kind of red light with the corner of my eye.

Once I’m in place, there are two ways that my head is secured in place:

A single-use plastic strip shaped like an upside down T, with a sticky patch in the intersection of the T that goes just above my eyebrows. The three prongs of the T are then secured behind my head.

A headrest cushion on the right side of my head, and the magnet itself on the left.

The technician checks in, and assuming I’m comfortable, begins the treatment.

The basic experience is:

The machine makes a sound like the windows startup noise

A cycle of about thirty quick pulses lasting about 3-4 seconds

About 10-12 seconds of nothing

Repeated for 18 minutes.

The technician offered me some soft-start options: the first few cycles at lower power, increasing each cycle until you get to whatever power level your Motor Threshold Test indicated. There was also an option for the first few pulses of each individual cycle to be softer.

For the first session, they set the magnetic field to 80% of the level we’d found with the Motor Threshold Test, then the second session was at 90%, the third at 100%, the fourth at 110%, and the fifth at 120%. I was told that 120% is the standard, given variability in how the brain responds to the magnetic field.

The Sensation

The doctor, in the initial appointment, described the sensation of the magnetic pulses as “tapping”, and that isn’t entirely inaccurate. Each pulse—each click—of the magnet feels a bit like a finger knocking poking your skull.

Given the speed at which the pulses occur, comparisons to woodpeckers have been made.

While the sensation is one of tapping, it’s important to note that nothing is actually tapping you; what you’re feeling is muscles spasming in response to being electromagnetically stimulated. Depending on the strength of the pulse, this goes from ‘annoying’ to ‘headache-inducing’.

At the higher power pulses, my skull would vibrate a bit, which made my jaw to chatter up and down. This led to some minor jaw pain, although it disappeared over the weekends when I wasn’t undergoing treatment. I got in the habit of sticking my tongue between my teeth as something of a shock absorber, and that seemed to help as well.

With this tapping sensation, I found it difficult to concentrate on anything while the treatment was ongoing; my clinic had a TV available if I wanted to watch it, but I generally didn’t.

I also found that breathing in or out while the magnet was going was uncomfortable, and so tried to time my breathing such that I was doing neither while the machine was pulsing.

Results

TMS worked for me. I don’t know how long the treatment is going to last (I was told that it’s supposed to last at least a year, with it lasting indefinitely for many), but it absolutely pulled me out of a very bad depression.

To use my percentage model, I went from ~15% to ~80% over the course of seven weeks. Interestingly enough, the improvement was pretty steady; I gained around 8-10% per week (which is part of how I was able to quantify the percentages).

It’s a commonly acknowledged idea that slow changes over time are more difficult to notice than fast, abrupt changes, but I am wildly better-off (mentally) than I was in August, and the difference is stark to me.

Conclusion

Depression sucks.

A lot.

I’ve ridden the antidepressant carousel all the way around, and while sometimes they’re miracle drugs, plenty of times they’re a pain in the ass. They have side effects, they take four to six weeks to build up in your body and therefore do anything, you have to keep getting prescriptions filled and refilled…it’s a pain.

TMS, on the other hand, is a large and exhausting up-front investment. You have to go in five days a week. There’s driving (there and back), logistics (you try to schedule that and a full-time job), and the annoyance of sitting in a chair while a magnet makes loud clicking noises and rattles your skull and rewires your brain.

But it works (for me).

And that makes it worth it.

I expect, just because life has taught me to be pessimistic in this, that the TMS will wear off in a year for me. This begged the question: if I had to do this again, or even in perpetuity—spend seven weeks a year getting TMS treatment for the rest of my life—would I?

Yes. A thousand times yes.

A Kodak moment might be priceless, but a functioning brain is worth a whole lot to me, and I can actually sell the labor the latter produces for money.

I’m not sponsored in any way, or telling anyone what to do. But it’s useful to know that there is another option for depression (and OCD and anxiety, which TMS is also used to treat). One that is powerful and reasonably fast and works.

Interesting, I really hope TMS gains more acceptance. By the way, according to studies, ECT (the precursor of TMS) is even more effective, though it does have more side effects, due to the required anesthesia, and it is gatekept even more strongly. In my youth I suffered from depression for several years, and all of this likely would have been avoidable with a few ECT sessions (TMS wasn’t a thing yet), if it wasn’t for the medical system’s irrational bias in favor of exclusively using SSRIs and CBT. I think this happens because most medical staff have no idea how terrible depression can be, so they don’t get the sense of urgency they’d get from more visible diseases.

I do think there’s something to that idea—physical injury and pain is a very universal and visible experience, whereas mental illness is difficult to parse for those who’ve never experienced it. I also think there’s some sense in which ‘treatment’ and ‘cure’ are treated differently for mental and physical illness.

A doctor wouldn’t just prescribe painkillers for a broken arm and call it a day because your symptoms have been dealt with; they’d want to actually fix the problem. Depression, on the other hand, doctors seem perfectly fine with merely mitigating the symptoms. Perhaps because that’s all they’re confident they can do?

Neither TMS nor ECT didn’t do much for my depression. Eventually, after years of trial and error, I did find a combination of drugs that works pretty well.

I never tried ketamine or psilocybin treatments but I would go that route before ever thinking about trying ECT again.

BTW, memantine is weak (but legal) analog of ketamine and helped me to cure my depression.

Hi Sable, I’m a TMS (+EEG) researcher. I’m happy to see some TMS discussed here and this is a nice introductory writeup. If you had any specific questions about TMS or the therapy I’d be happy to answer them or point you in the right direction. Depression is not my personal area of study or expertise, but it’s hard not to know a lot about depression treatment if you study TMS for a living because it’s the most successful application of the technique.

Two specific things you mentioned—first, that TMS depression therapy does not require or use an MRI. It’s right of you to point this out, because doesn’t it seem obvious that if we targeted based on the brain’s structural or functional properties we could give better therapy? The answer is yes, and it’s frankly a miracle that TMS works for depression without this kind of targeting. Still, there is still a strong intuition that the current therapy leaves a lot on the table, and lots of labs are studying how to make it better in depression, other dysfunctions and in healthy cognition. This is close to my area of research, which is broadly to investigate what spatial or temporal information about the brain is useful to make a given therapy or research intervention better and develop techniques for actually using it.

The second thing I noticed was your frustration that you have to fail medications to get approved for TMS. This is super frustrating, but I think it’s just about caution in the medical community rather than any first order conspiracy by pharma. My sense is that medications still work better for most people, where “work better” is a conjunction between the raw effectiveness of the therapy and treatment adherence (which as you mentioned is a not-convenient aspect of TMS for depression). A related issue is that the medical community knows how well medications work and so are in some kind of Hippocratic contract to force people try that first before offering the “experimental” thing. Even though it’s over a decade old now, TMS depression therapy is still considered pretty experimental. Epecially the kind it sounds like you got, which is an accelerated course.

I’m really glad the therapy worked for you, thanks for bringing this content to LessWrong.

That’s awesome that you’re doing that research!

My biggest question is probably what the distribution looks like for people who get TMS for depression—how many of them are “cured” in the sense that they never need TMS again? How many need it again after a year? Two years? And so on.

Took me a while to get back to this question. I didn’t know the answer so I looked up some papers. The short answer is, knowing this requires long follow-up periods which studies are generally not good at so we don’t have great answers. Definitely a significant number of people don’t stay better.

The longer answer is, probably about half of people need some form of maintenance treatment to stay non-depressed for more than a year, but our view of this is very confounded. Some studies have used normal antidepressant medications for maintenance, and some studies have tried additional rounds of TMS, both of which work really well. Up to a third of patients experience “symptom worsening” meaning that after an initial improvement from TMS, their symptoms actually get worse than when they started, but apparently more TMS can fix this in most people? I wasn’t completely sure what they were saying here. So yeah, it isn’t great. A lot of people need maintenance of some kind. This could very well correlate with whether your depression is the “life circumstances” kind or the “intrinsic brain chemistry” kind, not that we have a great handle on differentiating those two either.

Furthermore, (1) there are a few modes of TMS therapy out there, including most notably the accelerated course, and there may be different relapse rates across these treatment modes. There is some handwaving that the accelerated course may be more effective in this regard but I don’t think we know yet. And (2) another important issue with interpreting these data is that many of the studies are done on people who are treatment resistant, such as yourself. It’s unclear how much the results translate to the general population of depressed people.

Overall this is probably not a very satisfying answer, I don’t really have the specialist inside view on this one.

FYI the most targeted paper I found on this topic is the citation below. Note that it’s from 2016. There is probably something more recent, I just didn’t have more time to dig.

Sackeim, H. A. (2016). Acute continuation and maintenance treatment of major depressive episodes with transcranial magnetic stimulation. Brain Stimulation: Basic, Translational, and Clinical Research in Neuromodulation, 9(3), 313-319.

This isn’t directly related to TMS, but I’ve been trying to get an answer to this question for years, and maybe you have one.

When doing TMS, or any depression treatment, or any supplementation experiment, etc. it would make sense to track the effects objectively (in addition to, not as a replacement for subjective monitoring). I haven’t found any particularly good option for this, especially if I want to self-administer it most days. Quantified mind comes close, but it’s really hard to use their interface to construct a custom battery and an indefinite experiment.

Do you know of anything?

Hey, I remember your medical miracle post. I enjoyed it!

”Objectively” for me would translate to “biomarker” i.e., a bio-physical signal that predicts a clinical outcome. Note that for depression and many psychological issues this means that we find the biomarkers by asking people how they feel...but maybe this is ok because we do huge studies with good controls, and the biomarkers may take on a life of their own after they are identified.

I’m assuming you mean biomarkers for psychological / mental health outcomes specifically. This is spiritually pretty close to what my lab studies—ways to predict how TMS will affect individuals, and adjust it to make it work better in each person. Our philosophy—which I had to think about for a bit to even articulate, it’s so baked into our thinking—is that the effects of an intervention will manifest most reliably in reactions to very simple cognitive tasks like vigilance, working memory, and so on. Most serious health issues impact your reaction times, accuracy, bias, etc. in subtle but statistically reliable ways. Measuring these with random sampling from a phone app and doing good statistics on the data is probably your best bet for objectively assessing interventions. Maybe that is what Quantified Mind does, I’m not sure?

The short answer is that if this were easy, it would already be popular, because we clearly need it. A lot of academic labs and industry people are trying to do this all the time. There is growing success, but it’s slow growing and fraught with non-replicable work.

Not my medical miracle post, just my comment on it.

Yes, though I wouldn’t restrict it to “clinical” because I care about non-medical outcomes, and “bio-physical” seems restrictive, though based on your example, that seems to be just my interpretation of the term.

These are legitimate biomarkers, but they’re not what I want, and I’m struggling to explain specifically why; the two things that come up are that they have low statistical power and they’re a particularly lagging indicator (imagine for contrast e.g. being able to tell whether an antidepressant would work for you after taking it for a week, even if it takes two months to feel the effects). They’re fine and useful for statistics, and even for measuring the effectiveness of a treatment in an individual, but a lot less useful for experimenting.

That sounds really cool. I’m assuming there’s nothing actionable available right now for patients?

Yep. This is basically what I’m hoping to monitor in myself. For example, better vigilance might translate to better focus on work tasks, or better selective attention might imply better impulse control.

QM doesn’t work so well on phone and hasn’t been updated on years and has major UX issues for my use case that makes it too hard to work with. It also doesn’t expose the raw statistics. Cognifit (the only app I’ve found that does assessment and not just “brain training”) reports even less.

Do you have a specific app that you know of?

I don’t think this is true. My alternative hypothesis (which I think is also compatible with the data) is that it’s not hard, but there’s no money in it, so there’s not much commercial “free energy” making it happen, and that it’s tedious, so there’s not much hobbyist “free energy”, and academia is slow as things like this.

My sister tried TMS and said it made her ears ring. Did you experience that?

I didn’t, but I’m not surprised your sister had that experience. It’s a loud, repetitive noise going off next to your ear. My clinic offered me earplugs, which I didn’t need, but perhaps your sister could have used?

Did the ringing go away over time, or was it permanent?

As I was reading this I intuited there would be something to predict here so I successfully stopped reading before the “left-TMS is for depression, right-TMS is for anxiety” part and scrolled it out of view so I could do the prediction myself based on what I understand to be the roles of the right and left hemispheres.

As I understand it, the left hemisphere of the brain is sort of focused “forwards”, on whatever tool you’re using or prey you’re hunting, and in particular on words you’re speaking/hearing and plans you’re making to pursue some goal. In contrast the right hemisphere of the brain is focused “outwards” on the environment as a whole and sort of on guard for any threats or interesting irregularities that ought to pull your attention away.

Therefore I predicted that left-TMS would be for kind of general depression stuff about all your plans seeming like bad ideas or whatever, and right-TMS would be for worrying about a bunch of stuff that’s in your environment and being distracted, which sounds more like either an ADHD kind of thing or anxiety!

So you’ll have to take my word for it, but I got it right.

first time I hear of TMS. I find it sus for the same reason as I find electroconvulsive therapy sus. like, what’s the mechanism of the healing? sounds like it scrambles your brain and the new configuration is not depressed. but given this effect on depression, I would be worried about having other parts of me scrambled.

I think TMS doesn’t rewrite anything, instead activating neural circuits in another pattern? Then, new pattern is not depressed, brain can notice that (on either conscious or subconscious level) and make appropriate changes to neural connections.

Basically, I believe that whatever resulting patterns (including “other parts of you changed into something non-native and alien”) you dis-endorse, are “committed” with significantly lower probability.

“activating in another pattern” sounds similar enough to “scrambling”. so are you saying, the brain will keep/change the patterns based on them being good/bad? it would seem partly likely (on my model), like say the motor function is scrambled in a useless way, it would be rescrambled into a way that works by learning, and if it happens to work better it would be kept. but it seems unlikely this process would strongly reflect my deepest intellectual endorsement. there could be conscious feedback fixing it, but the worry extends into the feedback “getting scrambled”.

additional thought: I’d be especially worried about “destructive” changes—compare to lobotomy, it was also a procedure done directly on the brain that was considered to cure stuff, but now we consider it bad because it was destroying stuff.

[uninformed neurology is fun]

when you’re stuck at the bottom of an attractor a hard kick to somewhere else can be good enough even with unknown side effects.

Your concerns are valid, but the changes seem to be subjectively very minor. And depression is very very bad. So it’s an easy choice for anyone with real depression.

Your self isn’t going to receive your deepest intellectual endorsement without TMS either; we don’t have time to understand and supervise every change in our unconscious.

How do they figure out what waveforms to use and at what frequencies on your brain? The ideal waveforms/frequencies depend a lot on your brainwaves and brain configuration

I’ve heard fMRI-guided TMS is the best kind, but many don’t use it [and maybe it isn’t necessary?]

Is anyone familiar with MeRT? It’s what wave neuroscience uses, and is supposedly effective for more than just depression (there are ASDs and ADHD, where the effectiveness is way less certain, but where some people can have unusually high benefits). But response rates seem highly inconsistent (the clinic will say that “90% of people are responsive” but there is substantial reporting bias and every clinic seems to say this [no way to verify] so I don’t believe these figures) and MeRT is still highly experimental so it’s not covered by insurance. Some people with ASDs are desperate enough that they try it. TMS is probably useful for WAY more than severe treatment-resistant depression, but it’s still the only indication that insurance companies are willing to cover.

I got my brainwaves scanned for MeRT and found that I have too much slowwave in ACC that could be sped up (though I’m still unsure about the effectiveness of MeRT, they don’t seem to give you your data to understand your brain better in the same way that the Neurofield tACS people [or those at the ISNR conference] do)...

BTW there’s a TMS Facebook group, and there’s also the SAINT protocol where you only take a week out of your life for the TMS treatment for more treatments per day). I’m still unsure about the SAINT protocol b/c it’s mostly developed just for severe depression and I’m not sure if this is what I have. There’s also the NYC Neuromodulation conference where you can learn A LOT from TMS practitioners and TMS research (the Randy Buckner lab at Harvard has some of the most interesting research)

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8122027/

Presumably Fourier transform or its developments can be used. (After all, light speed is negligible at the scale we’re considering.)

Fascinating. Sounds related to the Yoga concept of kryias.