Manifold Predicted the AI Extinction Statement and CAIS Wanted it Deleted

Crosspost from https://news.manifold.markets/p/manifold-predicted-the-ai-extinction

History may look back on CAIS’s AI risk statement as a pivotal moment IF we survive AI.

But, what if I told you that AI researchers “leaked” info about the statement on Manifold Markets over a week before it was published? This justifiably led to CAIS requesting the market to be deleted, concerned that it could damage the impact of the statement.

To provide some background, the statement was signed by the likes of Sam Altman, Demis Hassabis, Dario Amodei and other prominent AI figures. Short and with gravitas it read:

“Mitigating the risk of extinction from AI should be a global priority alongside other societal-scale risks such as pandemics and nuclear war.”

Imagine if the CEOs of major oil companies banded together in the 1900s and told their respective governments, “We need to be careful about building infrastructure relying heavily on fossil fuels. It could be catastrophic for the environment long term.”

This may seem like an extreme comparison to make, but the reality is leading AI companies consider the risk significant enough to compromise on profit and progression. Well, that’s what their words say, time will tell how it is reflected in corporate decision-making.

I had an opportunity to talk to some of the insider traders and Dan Hendrycks from CAIS, and hope you enjoy a breakdown of one of our craziest markets and what we’ve learnt from it.

Background on Manifold Markets

Prediction markets allow people who lack expertise about certain topics to form precise models of what the future could look like thanks to the live-updating probabilities that are generated by traders. Trades can buy YES or NO shares, which fluctuate in price depending on the current probability (similar to sports betting odds).

Manifold Markets uses play money, which leads some to express skepticism of its efficacy. However, data suggest Manifold Markets are incredibly accurate!

Here is a graph from an analysis of Manifold Market’s calibration carried out by Vincent Luczkow. This places markets into buckets based on their probability at the middle of their lifespan. It then looks at the percentage of markets in each bucket that resolve to yes. To be well-calibrated, you want markets in the 10% bucket at their mid-point to resolve yes 10% of the time and no 90% of the time (this ideal is represented by the green line on the graph). Pretty accurate! Also, check out our calibration page or our performance on the midterms.

Manifold Markets is unique from other prediction platforms as its markets are all user-generated questions. Users have used our markets to make predictions about everything you can think of from global nuclear risk to their personal romantic endeavours. The core denominator between these markets is the mechanism used to generate the probability that predicts an unknown future event.

But what happens when you defy this, and a market is created by someone that does know the future?

The Tale of the Statement on AI Risk

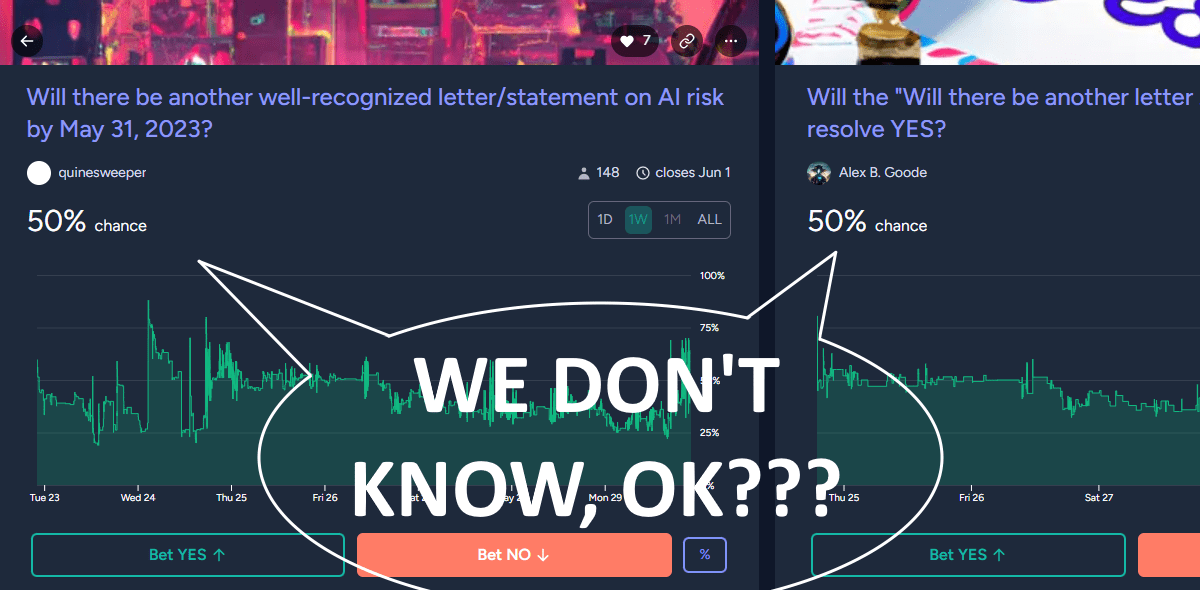

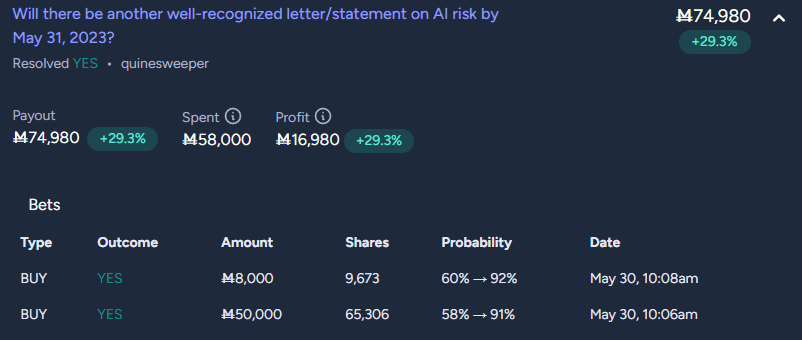

It all started on May 20th, when a user called Quinesweeper created 3 markets titled, “Will there be another well-recognized letter/statement on AI risk by May [June, July] 31, 2023?” Whenever I write, “the/this market”, I will be referring to the market which was asking if the statement would be released before the end of May.

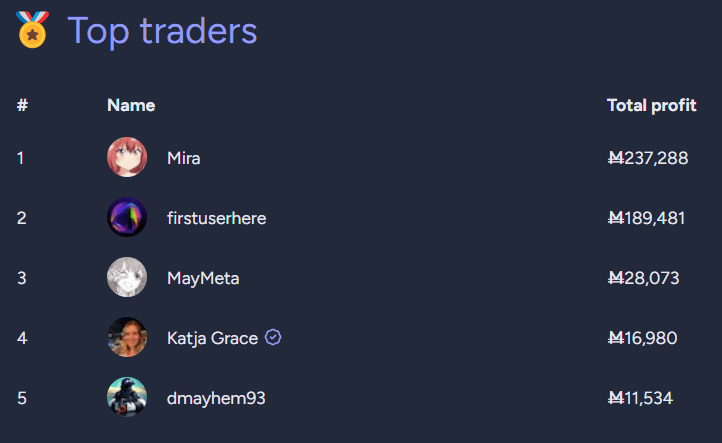

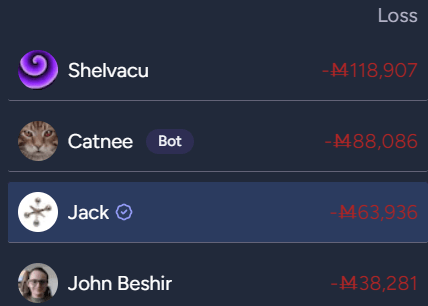

I’m including a screenshot of the traders who won the most profit and an annotated graph below which will be referenced throughout.

Initial trading

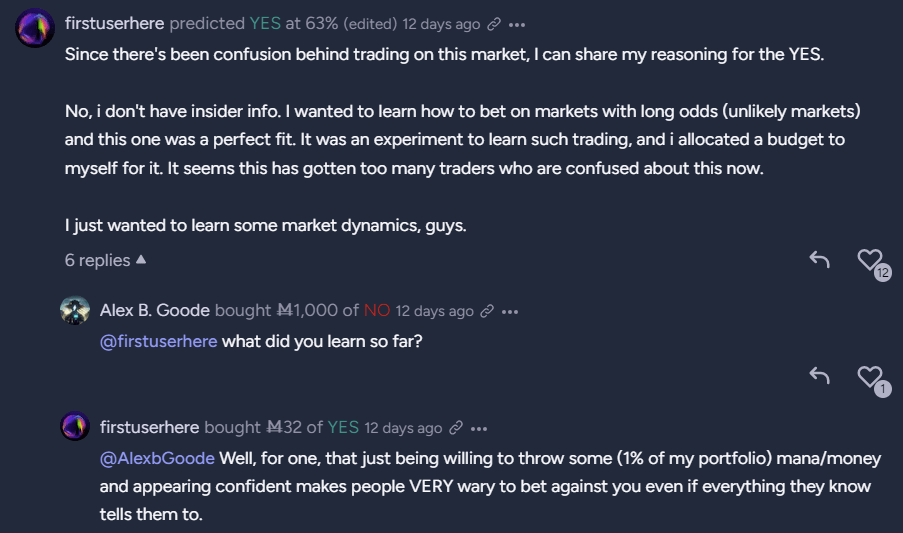

All markets start at 50% when created, but this market was quickly bid down to 10% by traders who had no evidence that a major statement would be published in the next 10 days. However, within the first few hours, there was already upwards buying pressure. On the first day, the only person betting yes was Firstuserhere, whose trades can be seen marked by the yellow dots.

Although Firstuserhere works on AI, most users on our site know him for being an active Manifold user, so didn’t default to assuming he had insider info. It’s also worth noting that at this point in time, the market had very little liquidity. The spikes caused by Firstuserhere were a result of bets around 300 Mana, the equivalent of $3USD. Because of this traders continued to push the probability of the market back down each time Firstuserhere bought YES shares.

Things became more suspicious when Quinesweeper made his first trade marked by the red dots on May 21st. Now there were 2 individuals placing increasingly large orders on YES, one of whom was the market creator.

Users started commenting on the market, with weak speculation that there could be insider trading. But because this was Quinesweeper’s first market, others feared he was planning to load up on YES shares and fraudulently misresolve the market to yes regardless of the outcome. The Manifold team assured users that we would fix the resolution if it was resolved incorrectly so that users could trade on their true beliefs, and not have to factor into their probability the chance of fraud.

CAIS requests the market is deleted

CAIS privately reached out to Quinesweeper and requested he delete the market. They didn’t want to risk the letter being prematurely leaked which would diminish its effectiveness, particularly as they needed time to onboard signees and prepare for press release. A reasonable request, and we will revisit why we decided not to and what we’ve learnt from it later.

In response to this request, Quinesweeper sold his Yes shares (causing the dip marked by A).

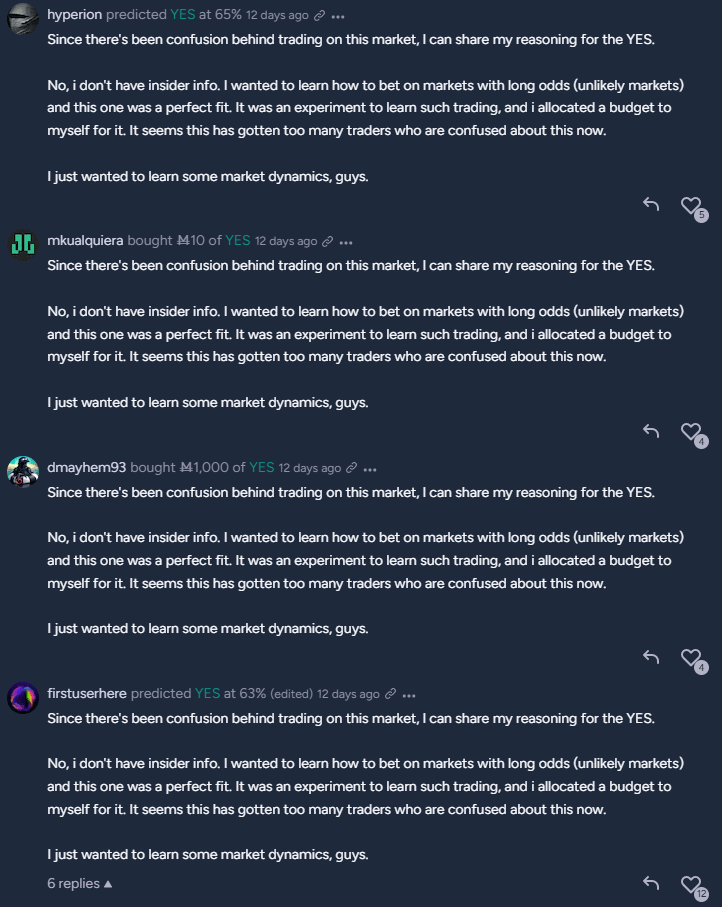

However, the market’s visibility only increased from here, as at mark B, another user known as Hyperion started participating in the market with insider information. A week later after the AI statement was released, he said in Discord,

“From my PoV, I saw the letter, list of signees, and release date early and told @mkualquiera and @dmayhem93 about it on the 23rd. We all bet YES heavily, then the market seemingly exploded in popularity after the people betting it back down put it on the front page.

It was also pretty obvious to me even early on that some of the YES bettors were people in the AI sphere and the NO bettors were largely not, if you know who people are.

A lesson I would recommend learning is that many AI markets on Manifold are heavily insider traded...”

It is unclear to me whether CAIS requested the takedown of the market before or after this peak in activity, but regardless, although Quinesweeper had already exited the market at this point, he had yet to unlist the market and it soon became trending.

He did quickly unlist it (making it only accessible through having the URL) and reached out to Manifold Markets to ask whether the market could be deleted. Manifold responded by stating that “We don’t have a policy of deleting markets due to infosec reasons,” and suggested alternate ways to draw less attention to the market.

One of these suggestions included using creator privileges to hide comments to reduce the visibility of comments that might leak information. However, we did state that we don’t necessarily recommend doing this as it could inadvertently draw more attention to the market.

Quinesweeper decided that he did want to hide some of the comments as shown above. The content of hidden comments can still be viewed by clicking them. Quinesweeper also changed his name (it had previously been his real name).

Inevitably, the combination of all these actions just brought more attention to the market as users perceived it all to be very strange and began discussing it in our Discord server and sharing links to it.

This brought more attention to firstuserhere, who held the most YES shares and was most well-known amongst YES bettors.

When researching for this article, I spoke extensively with Firstuserhere. He explained to me that at this point in time, he had reason to suspect that there was a letter, but didn’t have any information about release dates. Thus, he felt comfortable stating he didn’t have insider info. He was being truthful about allocating a budget between the 3 markets with different time periods to learn how to spread his budget between them.

As the market gained traction, he began noticing people trading on it who he had previously worked with and knew were likely to have insider info in the AI space. He privately reached out to them and they were able to confirm his suspicions and the planned release date. People continued to assume that his original statement still held true and that he didn’t hold insider information, so he decided to stop commenting but continue to amass YES shares through large limit orders.

At this point, the Yes traders with insider info decided to do some damage control. It is not clear to me whether this was to encourage people to continue betting on NO so they could continue to buy more YES shares, or if they were actually concerned about a leak and were trying to protect CAIS.

Regardless, Hyperion’s trio began this copypasta in the comments. Others soon joined in and people thought it was just a meme to buy some YES shares and paste the copy pasta.

Turning the market into a meme

The strategy to decrease the visibility of the market had failed, so instead it was time to sow chaos and invalidate speculation of insider trading by turning everything into one big meme. And so, insider Mkualquiera and others began producing these banging memes.

It was here at point C that Mira decided to join the market and began market-making to capture value from the volatility of the market. This is done by setting up limit orders for both YES and NO shares (eg. buy NO at 60% and Yes at 40%). These shares cancel each other out, but you capture profit due to the difference in price between the shares at 40% and 60%. MayMeta, the number 3 profiter, had also been market-making the entire time and continued to do so until the final few hours when they switched to YES.

This led to the market converging to the Schelling point, aka 50%, which tends to happen in these big markets when no one has any idea what is going on. This isn’t just due to, “Oh we don’t know, bet it to 50%”, but rather the math behind the pricing of shares on the market.

Firstuserhere has also informed me that a few YES insiders agreed to not buy the market above 55% so they could conceal their continued accumulation of cheap shares. They really were working together to maximise how much profit they could make off of the ignorant NO bettors.

From what I can tell, turning the market into one big meme worked surprisingly well, and some users genuinely believed there was no statement, and that the only reason the probability was so high was “for the memes”.

Other users still suspected there was a letter and insider trading due to the strong signals from the YES traders prior to the memes. However, the release date was still obfuscated due to the creator making markets for June and July and suspected insiders buying shares in all 3.

This led our top trader and forecaster Jack, to buy NO shares on the May market but YES shares on the June and July markets following the Kelly criterion to size his bets. This led to him losing a sizable amount of mana, although he was able to recover a portion of it thanks to his YES shares on the other markets.

This is what Jack had to say in Discord after the market concluded,

“I was 95% sure there was inside info of some form on the market. I was fairly confident that firstuserhere was trading on a mix of gossip/rumor and deduction based on the more well informed insiders’ trading. I also observed that firstuserhere was buying up to 90% on the June/July markets and only up to about 30-40% on the May market (until the last couple days when they bought up to 70%).

I therefore deduced that the timing of the letter was likely uncertain, and predicted accordingly. As of yesterday [May 29th] my prediction for by May, taking into account all information, was 55% and I made a Kelly bet accordingly. In retrospect I probably should have updated further up.

Part of the problem for me trading on this prediction was that it was far easier to get large fills on my orders when buying NO than when buying YES. I also predicted 90-95% for by June/July, but unfortunately nobody was buying much NO over there.”

Jack then made a market on if he will believe the AI risk letter markets were priced rationally. He resolved this to 80%, reasoning that the June and July markets were reasonably priced, but the May market was underpriced. His final reflections can be read in the comments of the market linked above.

The Final day

The memes continued until resolution. However, a few traders did change their strategies towards the end. Mira was mostly profiting from market-making, but did also hold YES shares. However, at point D Mira decided to abandon their market-making strategy and went all-in on YES shares, investing over 150,000 mana worth of YES shares ($1,500). Firstuserhere later revealed that Mira privately confronted him before making this decision.

Katja Grace, a known writer who frequently discusses AI (check out her recent piece in the Time magazine!) entered the market with her first trade buying the market from 59% to 92%. Her bets were placed at 10:06am, whereas the statement was shared by CAIS on Twitter at 10:30am.

I reached out to her about whether she had insider information or if she was simply the fastest to react to the news, and this is what she told me:

“A combo—I had insider information (I signed the thing earlier), including having heard a rumor that it would be released at 2am [10:00 BST]. I stayed up to 2am refreshing the page, and as soon as I saw it become public I bet on it.”

And with that, the market came to an end. It was encouraging to see how seriously it was perceived compared to the previous letter. It headlined the news and has been a vital step in initiating talks within government bodies about AI risk. Knowing that thanks to our markets, several non-insiders were able to infer that the statement was going to be released 1-2 weeks before it actually did, was fascinating to see.

Should Manifold have taken down the market?

Quinesweeper first messaged Manifold on the 23rd, asking if the markets could “be deleted at the request of an organisation”.

Austin responded by informing him that we don’t have a policy for deleting markets for infosec reasons. Manifold Markets believes in radical transparency—almost all of our Notion work documents, salaries, and internal meeting notes are public.

CAIS never directly reached out to us and it was only after the statement was published that we learnt it was about them. I’m not sure what we would have done if we had the full-context and the request was made directly.

However, now that we have the full picture, I agree that if the market had caused the statement to prematurely enter the news cycle, it could have diminished its effect. The statement had been mistakenly indexed by Google, so was discoverable if someone was prompted to dig hard enough.

When reaching out to Dan Hendrycks, Executive & Research Director at CAIS, for comment he said,

“We were unhappy about the market, as it seemed to provide an unnecessary risk regarding the statement…

We felt it was crucial in having the time to prepare our media efforts. If the statement leaked early, then we might not have had a press release or statement prepared for the media…

As an example, sloppily rushing a book or an article would not improve epistemics. Likewise, rushing out the signatory letter would harm its overall effect. As such, even though the market would improve epistemics around whether a signatory letter would be released, we strongly feel that this would have reduced epistemics overall.”

That being said, under different circumstances this question COULD have had more upsides than downsides:

If the probability was very low, it could prompt someone to start working on one.

Building anticipation and hype resulting in a more prominent announcement.

Unfortunately in this case, the first point was null, as the market was created by an insider who already knew there was a statement in the works. The second point is a weaker one, particularly with Manifold’s current size.

A market’s inherent net value is only clear after it resolves (if even then), and thus for now Manifold likely will continue to not delete markets for infosec reasons. But, we haven’t had the chance to fully discuss this within the team, so don’t take this to be a hard stance.

Deleting a market is unprecedented, so even if we were convinced that the market does more harm than good, it probably wouldn’t be the solution due to the attention it draws.

What could have been asked instead?

Most people don’t know what information is actually valuable to know and thus the right questions to ask. I think this is often seen by hyper-fixation on the end result, and not having an understanding of the key factors that have the largest influence. One of the reasons forecasting the timeline and probability of extinction from AI is so challenging is that we aren’t even sure what some of the key factors that could cause/prevent it are. We need to be able to predict this, before even beginning to evaluate their respective probabilities and their effect on the end result’s probability! See the relevant market created by Eliezer Yudkowsky.

Here are some examples of questions with higher potential value when asked at an appropriate time. I’m sure someone with a firmer understanding of the AI space could think of even better ones!

“Will the next AI statement make a significant positive impact?”

Nuanced resolution criteria would have to accompany this question for it to be useful. But, you can see how predicting this could help people decide whether working on a statement is an effective use of resources.

“If another AI statement is released in May/June/July, will there be evidence it prompts discussion in the US government?”

This could help determine when the most impactful time to release a statement.

You could also make sub-questions such as: “If another AI statement is released in 2023 AND signed by Sam Altman, will there be evidence…” This could help determine who to prioritise to sign the statement.

“Which organisation is most likely to release the next AI statement?”

This could help people coordinate without necessarily revealing sensitive information.

“Will the next AI statement mention X thing?”

Help spark discussion on what is worth mentioning, with people predicting accordingly what they believe the leaders in the space will decide is valuable to include.

When maximising the value of a question, you should ask yourself two things:

Is the information I learn from this actionable in some way?

And if not:

Will this provide informative data on something that is being asked/discussed that is important for people to perceive correctly?

I think most markets do fulfil point 2 in some way, but the extent of which is quite opaque.

Conclusion

First off, I want to apologise on behalf of the Manifold team to CAIS for any stress our markets may have caused.

Even though prediction markets hold a wealth of untapped potential, we need to be careful to avoid pitfalls. Users creating markets shouldn’t overlook the types of impact their market may have, and ultimately, the Manifold team is responsible to make sure users aren’t perversely incentivised. If a market is created because AI researchers want to pretend to be politicians’ spouses for a day, then there is room for improvement!

That being said, the vast majority of our markets are created with good incentives, and it still astounds me that we can conjure accurate probabilities about most future events so easily using prediction markets.

Here are a few examples you should check out:

Raise awareness by providing a grounded, quantified figure. After reading other media which leans into uncertainty and hypes up worrying possibilities, it’s always refreshing to visit Manifold to see a realistic outside view. Although, in the case of AI extinction perhaps less so…

“Personal” market that provides helpful information to the creator to help with managing planning/expectations. Can also act as additional incentive and accountability in some cases.

Provides an outside view to improve people’s understanding of the world.

It would be remiss of me to not include this market, which just resolved Yes last Friday after one of our founders got married (they were single when Manifold first started 1.5 years ago)!

The net value each individual market provides is often hard to foresee, but the fact we are already at a stage where their potential for impact warrants vigilance is a bullish signal. We will continue to work to improve epistemic practices, build a community that facilitates thinking in probabilities, and make forecasting accessible and fun to the average person.

If you felt inspired by this article to create some questions for your own organisation, but want to do so in a contained environment to minimise risk, then check out our recently released feature—private groups!

Thanks for reading ^^

When insider trading happens in the stock market, it’s usually not the exchange that is liable or responsible for doing anything about it.

If traders with inside information were trading in this market, I’d like to know how they came to know the information, and whether those who shared it agreed to abide by an embargo.

If someone who agreed to abide by an embargo directly traded in the market or knowingly shared information with someone who did, I would consider that an ethical breach. If the sharing was unintentional, I wouldn’t consider it a breach of ethics, but I would question that person’s ability to keep secrets of even mild importance in the future.

If insiders learned of the letter’s existence through more tenuous or indirect links, I still think this is a failure of secret-keeping on the part of CAIS and the signatories, but it may be that there is no one person who is directly responsible. Still, we should strive for better secrecy when it matters, and remind everyone of the basics of information-theoretic secret keeping (act exactly as you would if you knew nothing, consider counterfactuals, etc.).

To add on to the point about information-theoretic secret-keeping, if Manifold, market participants, and people with secrets want to not leak info in the future, my advice for each group is:

Manifold: as a blanket policy, never delete markets, at least for any reason that is causally related to the topic or question of the market. Even taking a market down quietly or on some unrelated pretext reveals a bunch of information to careful observers, and might result in a Streisand effect that causes the info to reach even non-careful observers.

Market participants: abide by embargoes that you have agreed to abide by. If you have not agreed to keep a secret or abide by an embargo, but learn some privileged information via a friend or acquaintance or other means, you may be ethically in the clear to trade on that information. But consider the reputational consequences that your source might suffer, and your future relationship with them, before exploiting their trust in you or their carelessness for manabucks.

Would-be secret-keepers: Glomarize, even when you don’t actually have secrets to keep. In particular, if you regularly create or participate in Manifold markets, you should not necessarily stop doing so when actually keeping a secret. If you did, people could exploit you by asking you to create or participate in markets, and note which requests you oblige and which requests you turn down. Either make (possibly known-losing) trades that you would have made if you knew nothing, or recuse yourself from all markets on which you might in principle have insider information about, and / or recuse yourself randomly. If you expect to have important secrets to keep (or if you don’t, but want to meta-glomarize), it might be better to institute a blanket policy now of not trading in or creating prediction markets at all.

Agree with the first two, and with the risk brought up in third point but not the conclusion of ‘avoid participating’. What about participating only in an inconsistent way, and responding to all requests that you create/participate in prediction markets with the response that acceding to such requests is against personal policy. That gives you the freedom to participate as you desire, but protects you from info-leaking via antagonistic request probing. Also, consider having an anonymous persona for participating in markets that seem like they might tempt you into revealing secrets you don’t reflectively wish to reveal in that way.

Yeah, there are probably various methods you can use and precautions you can take to participate securely without leaking any significant information. But any such plans are necessarily more complicated and carry more risk of screwing them up than blanket abstention. As the importance of the secrets you have to keep goes up, the benefit of simplicity probably outweighs the benefits derived from participating in prediction markets, especially play money ones.

Where someone personally draws the line on whether to participate or not depends on: the relative value they place on keeping secrets, how many important secrets they have, how much benefit they derive from participating in prediction markets, and how much they enjoy implementing complicated information-theoretic secret-keeping schemes.

These are fairly general, and pretty easy to agree with, ignoring any conflicts of intention (a participant might WANT to leak information or make money, even if there’s an embargo).

Note that #2 and #3 are contradictory. One cannot simultaneously abstain from a question AND participate randomly. More important, in a well-functioning market, making incorrect bets actually costs you—this is an expense to maintain secrecy, and a pretty big and painful one, especially for participants who otherwise love that information markets … provide information.

It’s extremely difficult to create a fraudulent company and get it listed on the NYSE. Additionally, the Exchange can and does stop trading on both individual stocks and the exchange as a whole, though due to the downstream effects on consumer confidence this is only done rarely.

I don’t know what lessons one should learn from the stock market regarding MM, but I don’t think we should rush to conclude MM shouldn’t intervene or shouldn’t be blamed for not intervening.

Agreed, most “fraudulent” listed public companies (on places like the NYSE, where they actually check stuff), fill weird conditions like:

being really old, to where their corporate history stretches back before modern high-standards checks.

being acquired/SPAC’d to allow a fraudulent private company to kinda list itself.

be based on a larger fraud that probably isn’t accounting/insider related.

(Disclaimer: not an expert, not financial advice.)

For financial markets, insider trading is illegal because it makes legitimate funding signals less accessible, because it reduces trust in the market. It DOES accelerate information of the market, it just has trust and financial-impact effects that makes it problematic.

For information markets, insider trading is JUST information. It makes the market more accurate.

Would insider trading work out if everyone knew who was asking to trade with them ahead of time?

I don’t see how the “Will AI wipe out humanity before 2030” market could be valid. That is, I don’t see how it can even represent the average belief that traders have accurately, not just that the question itself seems extreme to me personally.

If “yes” can’t make money in either outcome, the market does not reflect probabilities faithfully.

It’s true that markets involving existential risk aren’t nearly as reliable as other markets. Perhaps I should have shown more care when using one as an example.

Ultimately for a market to be efficient, users have to be incentivised to trade to the best of their ability. Whilst the AI risk markets aren’t going to be particularly accurate, I do think that the one I linked is reasonably representative of our user’s beliefs. There is a good amount of upward and downward buying pressure on either side. My main concern with its accuracy is how many Yes shares Catnee has, however, the market does seem fairly stable at 25% and isn’t being held there with huge limit orders or anything like that.

One of the advantages of play money is that the incentive for truth-seeking can actually outweigh the desire to profit. This sort of market would obviously never work if real money was on the line!

I thought there was a vibecamp market that was deleted, last year?

Oh interesting, that’s news to me if true, but could be the case! I’ll have to ask Sinclair.

The “strongest” thing I have ever done with mod powers is to fix the misspelling of an answer in a free-response question at my friend’s request. Someone at [unnamed big tech company] once asked me to delete their market about whether the company would [do a thing companies often do] because their boss told them, but I unlisted it for them and told them to resolve it N/A.

I think we have ever deleted markets, but only for breaking community guidelines. I’ve never done it myself.

I’m just trading karma for manabucks, guys.