Procedural Executive Function, Part 3

The Off Road project has since been folded into Rethink Wellbeing, but I’ve continued working to better understand and treat Executive Dysfunction. You can read more about the project’s origins here.

If you haven’t, I suggest reading the start of my overview and exploration of Executive Function. Parts 1 and 2 of Procedural Executive Function can be found here and here.

TL;DR—Organization is the system of habits and external aids that minimizes effort for accomplishing work.

Working Memory is your capacity for holding information in your attention at once.

Flexible Thinking is your ability to creatively problem solve and avoid getting stuck.

Each helps you maintain progress on your goals, and can help maintain flow by reducing difficulty in solving problems, which is one of the main bottlenecks for productive work.

As we begin the final(?) installment of the series, I hope it’s clear now how the many parts of Executive Function work together to take someone from an initial notion about what they “want to do,” to actually doing it.

We can generally put the problems our executive function faces into two buckets: things that prevent us from starting something, and things that cause us to stop doing something.

The first post, covering Planning, Prioritizing and Task Initiation, addressed things in the first bucket. The second post’s contents, Self Monitoring, Impulse Control, and Emotional Control, address things that can be found in both buckets. And this post’s topics, Organization, Working Memory, and Flexible Thinking, largely have to do with things in the second bucket.

But this frame falls apart, a bit, if we zoom in to each step of the path. Do we ever “write an essay?” Or do we write sentences that make up an essay? Each sentence is of course itself made up of words, and each word is made up of letters, but when people say “I have writer’s block,” they don’t normally mean they’re blocked at the level of “I don’t know how to spell a word.” Sometimes they mean “I don’t know the best word to put here.” But often they mean something like “I don’t know what the next sentence should be,” as a subpart of “I don’t know what the next idea to start exploring is,” or “I don’t know how to best explain this idea.”

Again, things that cause us to “stop” doing something are often the same sorts that prevent us from starting the next bit.

As mentioned in Part 1, the tradeoff of “predicted fun/reward” vs “suffering/cost” is often the best measure of how hard someone will find a task to begin, and this extends to each subtask that makes up the overall goal. If you imagine doing something and the primary feelings are all aversive, such as boredom, discomfort, confusion, hopelessness, etc, then you could be reacting to the overall task, but you also could be reacting to some necessary part of it that you expect to be blocked on.

So, while some tasks are so short or straightforward that difficult problems don’t appear, the process of being able to continually engage in and complete “productive work” requires the ability to adapt to each new problem that might come up in the course of doing a task (or, if the work is boring, ways to stay stimulated and engaged if some part of it becomes monotonous).

Which is where Organization, Working Memory, and Flexible Thinking come in. When all’s well, these things help keep us engaged and capable of solving problems as they arise until the task is done, or at least until we need a break. But if any of them aren’t functioning properly, we’re at risk of feeling stuck, which we often experience as “getting distracted,” at each problem that comes up, whether on the level of what word to write next, or whether the essay really means anything at all.

So… how do we prepare to solve a stream of unpredictable, potential problems?

Organization

This section might seem overly obvious, or a kind of “pull yourself up by the bootstraps.” After all, part of how executive dysfunction manifests for many people is not being able to get organized!

But it’s important to recognize what organization is for if we want to understand what goes wrong, and how it can help. And to do that, we need to focus again on what it means to get “distracted” by something.

In some situations, getting distracted is a direct effect. Our awareness brings us a new stimulus that isn’t caught by one of our subconscious filters, and our attention shifts to it, or a stray thought occurs to us that immediately grabs our attention.

But for other situations, maybe even most, getting distracted is a symptom. It’s not a sudden, hard to ignore new stimulus that pulls our attention away from something else. It’s the result of your attention seeking something else to distract you from the discomfort or frustration or anxiety of not knowing what to do next.

The first is like a rock through your window. The second is like a vacuum, pulling in anything that will fill it.

Understanding this difference in what it means to “get distracted” is important, because it’s within that difference that we see what’s within our power and what we can do differently.

So, what causes that vacuum to appear? What are the conditions that get our brains to start roaming?

Back in Part 1, I mentioned that the main two things I’ve found have kept people from starting tasks is either predicting failure, or predicting discomfort. In the same way, basically all the reasons people don’t continue to do something they’ve started doing is that they didn’t know what to do next, or predicted it would be unpleasant to do.

Any kind of friction while doing something can inhibit what I call “next step momentum,” leading to the automatic seeking of other stimuli that’s more rewarding or less effortful or stressful. The less uncertainty there is between one step and the next, the less effort transitioning takes, the fewer parts of your executive function chain are going to trip you up in general.

And again, as mentioned during Task Initiation, sometimes a person’s executive function falters because they forgot to fill their gas tank, and the thought of having to make an extra stop on the way to the gym is too discouraging. Sometimes people working on a book or essay don’t know what parts they should write in what order, and an “ugh field” develops where just thinking about it feels bad, because they don’t know how to even begin the process of deciding what order to go in.

Those same things occur when obstacles come up in the middle of a process or project too, not just before we start. Our momentum is affected by all the same things that might block us; how close, physically, are we to the thing or place we need to take the next step? How much knowledge do we have of how to do it? Do we have the right tools?

All of which is why putting some work into organization ahead of time can help avoid things that break that flow.

Breaking Tasks into Smaller Steps: This is one of the widely given pieces of advice for a reason. The smaller and more concrete the next step is, the less likely we are to get frozen in uncertainty or confusion, and the less susceptible we are to distraction. Having an organized list of steps can also make it easier to get started, and reduce the feelings of being overwhelmed by the vagueness of a task.

There’s a big experiential difference most people feel between “I need to figure out how to apply for this government program” and “I need to go to X website, fill out Y form, and make an appointment at Z office to hand it in with any of these kinds of proper identification.”

Visual Aids: Some people might feel more overwhelmed by a long list of “to-do”s, but even sticky notes with tips or reminders on the edge of your monitor or various parts of your desk can be useful forms of external memory support that keep you from getting stuck when you’re not sure what to do next.

If you are someone who likes task lists or outlines, workflow diagrams can combine visual aids with breaking tasks down. Having an easily accessible reference sheet we can check keeps us in problem-solving mode, which is much more motivating than the void of uncertainty or confusion.

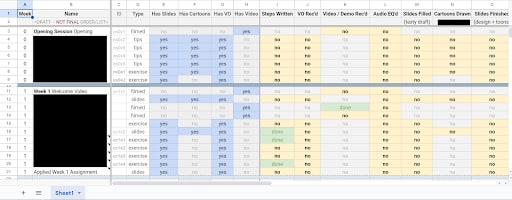

A friend of mine showed me the project outline for a web course she planned to create, and if the following image doesn’t produce visceral anxiety:

then I highly recommend something similar for any long and multiphase project.

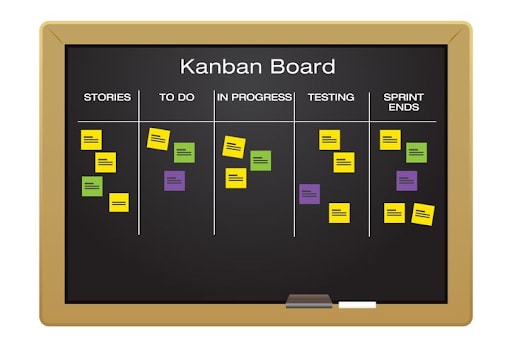

If it does produce deep or prolonged anxiety, then maybe something simpler like Kanban boards might be better:

The best tool or system is whichever one most helps you (yes you, specifically) minimize the amount of time you spend unsure of what to do next, and the one that helps minimize the chance that you forget to do something entirely.

An extra benefit of this kind of organization is that it lets you pick and choose more easily what you have the capacity for at any given moment. If your project allows you to choose what order to do what tasks in, having the reminder that you don’t have to do the big, scary, difficult next step and still get productive work done can be very valuable.

Decluttering Spaces: Whether it’s through clearing your desktop or the top of your desk, reducing distractions makes it easier to find what you need and not have your attention caught by something else. Every bit of potential friction, including a few moments of “Where did I put that…?” can contribute to cognitive overload or trigger a path-of-least-resistance into something less taxing or more rewarding, like opening social media or a game.

This is probably a good place to mention that “declutter” doesn’t necessarily mean “empty” or “bland.” Some people work better in a stimulating environment rather than a static one. Some would find a room full of comfy bean bags and backjacks detrimental compared to a work desk, but for others the work desk would kill their productivity after ten minutes due to physical discomfort. A cozy room with lava lamps and a cat in it is perfectly valid so long as it works for you.

Similarly, some people need silence to focus, while for others a good way to declutter their soundspace is to play music. Personally I find music without lyrics (or lyrics in a different language) particularly helpful for maintaining mental focus, and sometimes I’ll even play the same song on loop for hours when I want to maintain a flow state.

But if there’s anything that you know reliably captures your attention and shifts it toward things you don’t want to be doing, it’s good to separate it out. This is a big part of why many people who work from home distinguish their workspace from their relaxation space, if they can.

Time Management: There are a number of reasons “pomodoro timers” work for many people, but the best general explanation I have is that they act as a form of mental offloading. Open-ended work sessions can be difficult to know how to orient to; dividing work into 25 minute chunks, with built in 5 minute breaks, serves as a form of external memory to pre-empt distracting thoughts related to when to take a break and whether to keep working.

Also, if you’re not in flowstate it can be really helpful to give your brain a rest every so often when engaging in deliberate executive function. For some people it’s a literal break away from whatever area or object they were using to do the work. For others, just swapping between a thing that takes lots of effort with minimal reward signals, and a second task that doesn’t take much effort while providing many, is enough to actually boost their productivity, even if they’re swapping often.

(For an example of this, I often find consistent writing over long durations easier when I can alt-tab to some RP I’m engaging in with someone, as the natural back and forth of whose turn it is to respond allows me to take regular breaks every 3-15 minutes and is naturally fun and easier. I also know people who do the same thing with turn-based multiplayer games, or who set the pace of swapping between work and a single player game themself, though I expect that last one is likely to be particularly hard for most people with some EF disorder.)

In a broader scope, effective time management lets you adjust plans and priorities based on changing circumstances, and having accurate predictions about what to do when. Whether you’re planning out a busy day or a multi-week project, if the time you planned to take on one thing starts making the rest harder, the feeling of overwhelm can make it harder to catch up.

Oh, and of course, no discussion of EF and time management would be complete without mentioning deadlines. Many people experience approaching deadlines as a sort of turbo-mode for their executive function and creativity, but there’s a whole separate post that would need to be written about how that works (and when it fails).

The main relevant bit for this overview is, if you know that you’re the kind of person who just does better with deadlines and are fine with last-minute crunches as your primary way to get things done, one thing you could possibly do beforehand is ensure you have all the tools you need, ready and prepared, so that your last-day-sprint has a minimal amount of distractions or unexpected frustrations. In general, doing a premortem for anything you care about going well is helpful.

Seeking Support: As mentioned in an earlier part of the series, people often have an easier time doing things when they’re doing them with others. Even when working alone, however, no matter what step of your project you’re on, an easy to reference list of all the people you can reach out to if confused or stuck can be really helpful in providing you with next-step-momentum at a critical juncture where you might otherwise end up frustrated, listless, or seeking distraction.

Make a list of people who have worked on similar projects or done similar tasks before. Add people who would be happy to act as rubber ducks, or generally brainstorm/problem solve with. Find a subreddit or web forum or discord that might be able to provide answers.

In general, it can be really helpful to make the mental motion of “seeking support” a part of your automatic reaction to noticing “I don’t know what to do next.” As mentioned in Part 2, the better you are at noticing those sorts of feelings when you have them, the more likely you are to act in an endorsed way to the experience of having them.

There are other things we could cover on the ways organization help with executive function, but that’s a good note from which to transition to the “next” part of the procedure. As a closing note though, keep in mind that all “organization” is meant to do is minimize distractions, friction, and loss of momentum. Some tasks need a little organization, some tasks need a lot, and you might not always know what you’ll need ahead of time. But we usually have some inklings of how to improve our workspace or work flow, if we give ourselves the time and frame to think about them, and if you don’t know how to do a premortem yet, I highly recommend learning how to.

As a final point, if you find yourself in an endless loop of Organization Hell, planning and organizing and meta-planning how you organize… pay extra attention to the Flexible Thinking section, and also, maybe look into some of the things that help with fears and anxieties tied to perfectionism.

Meanwhile...

Working Memory

Most people think of memory in terms of “short term” vs “long term,” a frame in which memory is all about retention of information. This brings to mind comparisons to a computer’s hard drive and RAM, and people might then model the brain as having two specific areas where “long” and “short” memory are kept.

But unlike computers, which store everything in discrete bits, human thoughts are pretty interconnected. Our bodies are constantly receiving, filtering, and processing sensory inputs from multiple sources, which means human memory systems have to span multiple parts of the brain to create the “mental workspace” where active thinking occurs.

In 1999, Nelson Cowan proposed the “embedded-processes” model[1], which put a greater focus on attention to presented stimuli, and stressed the role of “capacity” for understanding the working memory concept. Basically, the more capacity you have to hold things in mind at the same time, the more complex thinking you’re capable of doing for longer…

But attention is one of the limiters. You can’t actively think about everything in your sensorium all at the same time.Which is why the more information you have “memorized,” the cheaper it is to shift your attention between ideas and let them work together. Ditto externalizing your thinking to a whiteboard or notepad, though as mentioned in the previous post, when focusing on any one thing, your attention will naturally shrink to exclude other bits of information.

Which, it turns out, is pretty important for executive function, a.k.a, our capability to follow through on doing specific things.

As I learned more about working memory, I’ve started to imagine memory’s role in executive function as similar to using my hands to build something out of lego.

Imagine if we had a big tub of lego sitting next to us, which represents all the information we have in our long term memory. Most of it is useless for any one task, but we don’t necessarily know which is and isn’t. Also, some of it is visible on top, while most is “buried” in the tub (which would represent our subconscious, as well as anything stored in “recognition memory”).

On our other side, imagine a conveyor belt carrying semi-random lego past us. Hopefully some of the pieces are needed for the thing we’re trying to make, but most won’t be. So long as we keep our attention moving to different things, that conveyer belt keeps moving. If we stop, it (mostly) stops, leaving us with what’s in reach, and of course what’s in our lego tub.

So we have a few options here. We could sift through the tub/our memory and see if anything feels useful… but it’s possible we won’t recognize the right pieces even if we feel them. We could also focus entirely on what passes us on the belt. Or of course we could try to mix things from the belt and things in the tub… whatever we decide, we can’t access the pieces that have already passed us, and for the purposes of this metaphor, we can’t keep any pieces we pick up until they snap together in a way that at least somewhat helps solve our problem.

And that process of fitting pieces together and seeing if they’ll snap into place, forming a step in the right direction for solving our problem? That’s where working memory comes in.

Our hands, like our working memory, can fit only so much at once. But they can try any combination that will fit, either from the new pieces of lego passing by, or legos in the tub. All you have to do is find a piece, decide to pick it up (which may require letting go of others), and hold onto it as you try combinations.

Which brings up some important questions, like “how many pieces can your hands hold at once,” and “how good are your hands at only picking up what you want them to?”

…Well, for most people “not many” and “not very.”

You might have heard that the average amount of “chunks” of information a person can hold in their active attention at once is four, but what counts as a “chunk” is a whole essay in and of itself, and it can vary wildly for different kinds of information. Some people can train themselves to hold a truly staggering amount of digits, but it’s unclear how much this level of retention translates into capability for manipulation of information.

In any case, the likely outcome when “trying to build an object out of lego” is that you’ll find yourself constantly changing out pieces, sometimes at random as you drop some and pick up others without a useful plan or intention. And since you can’t hold many at once, any new pieces you pick up might make you have to start all over again until you just happen to get the exact right combination, without any wasted pieces.

To make things more complicated, what if instead of a box full of lego pieces you have a box of mixed lego pieces, roblox pieces, hard candies, bits of colorful paper… and instead of a single conveyor with only lego on it, there are a dozen of them all snaking around you, each with a mix of things on them?

We can even imagine all sorts of variations of this metaphor to incorporate diagnoses that affect executive function like ADHD. What if the room is filled with different colored strobe lights? Or what if the candy feels warm and soft while the lego blocks feel sharp and cold? For things like mania, what if the room is dark, and only a specific and ever changing set of pieces glow? For things like depression, what if some people’s arms get more tired than others more quickly?

It’s worth noting that learning something new, or applying new knowledge, also uses up our “working memory hands.” Learning something new while at the same time trying to apply it in whatever task we’re doing can be very taxing, and quickly lead to mental fatigue… which often leads to our attention simply going elsewhere, wanting to do other things that are less effort and more rewarding.

Hopefully it’s clear why difficulty with this can affect executive function, but for those who want more grounded models of what’s happening in the brain, and how we know memory is integral to executive functioning at all, we can examine the brain itself. Our prefrontal cortex is the primary source of all our executive function, a “Central Executive Network” that connects with other areas to engage in various cognitive processes:

Episodic Buffer: The temporary storage system that modulates and integrates different sensory information for us to work with. To “create” this, the CEN routes through our anterior cingulate cortex, which is our attention controller, into the parietal lobe, which is for perceptual processing.

Visuo-Spatial Sketchpad: Our ability to not just visualize things, but also remember the relative positions of things in space, like where we parked our car or what the next step in a series of directions we should take is. This requires our CEN to link up with our posterior parietal cortex and occipital lobe.

Phonological Loop: Our ability to perfectly recall things we hear or read before they get stored in long-term memory, or lost. This involves Broca’s area, which is part of our complex speech network interacting with the flow of sensory information from the temporal cortex, and Wernicke’s area, which is where speech comprehension and understanding written language come from, both of which are part of our cerebral cortex.

The sheer variety and number of parts working together to create our working memory means a lot of different things can go wrong at this step in people’s ability to have “healthy” executive function. For example, damage to Broca’s area causes a form of aphasia where people speak in a jumbled “word salad” even if they clearly know what they want to say. Wernicke aphasia makes it difficult for people to understand others, and their ability to speak is also affected; they can convey intelligible thoughts, but usually limited to just a few words at a time. Both of these disabilities have been found to impair even non-linguistic executive function.

Other things that affect working memory include age (worse as we get older[2]), hormones (estrogen seems to improve it in older women[3],but testosterone boosters don’t help retain WM in aging men[4]), caffeine (mixed, but potentially negative[5]), and emotions (super mixed and also weird[6]).

This also means there’s a variety of approaches people can take to try to improve their working memory… but reviewing studies trying to pin down the effect of this can be discouraging.

For example, some[7] studies[8]suggest that stroke victims with aphasia benefit more from working memory exercises than they do routine speech therapy, and the benefits from working memory training also seems to help children with spastic displegia cerebral palsy[9].

There’s a lot of research out there that shows a mix of outcomes when trying to isolate the effects of working memory training on executive function[10]. For people without some explicit medical diagnosis that affects EF, this study[11]reported that transferable benefits weren’t found to a statistically significant degree beyond the participants’ ability to get better at specific skills trained.

In other words, if there’s nothing specifically “interfering” with your natural working memory, there isn’t much evidence that training it will improve your executive function.

Buuuut if my model of Procedural Executive Function is correct, I do expect it would be hard to notice improvements in EF just by addressing one part of it… especially when the part trained isn’t the participant’s specific “bottleneck,” or not their only one.

There are in fact many reasons why measuring people’s executive function is genuinely hard, not least of which is the very first point I emphasized at the start of all this: “is your executive function the problem, or are you trying to do things you don’t actually want or need to do?”

All of which is to say that while the research so far paints a muddy picture, I encourage people who believe WM is the main bottleneck for their EF to do some reading of their own and decide if it’s worth trying to deliberately improve it. I’d be very interested to hear first-hand accounts if you believe 1) this is your specific bottleneck, and 2) practicing exercises to improve it helped your memory, but not your executive function.

(As a side note, I’m fascinated by the question of whether those with aphantasia (who lack the experience of having mental imagery) develop workarounds to visual processing such that they don’t experience[12] the same limits[13] as those who undergo brain damage to their visual processing center, or if their brain does in fact utilize those portions and they just don’t experience the phenomenology. If scans have been done to distinguish this I haven’t found any. (I suspect people without an “internal monologue” are similarly unimpaired compared to those who suffer from either form of aphasia.))

For everyone else, let’s talk about the last most likely bottleneck in executive function…

Flexible Thinking

To begin the ending, let’s take seriously again the notion that “doing things” is just a process of repeated, fractal problem solving.

If you manage to do a thing you want to do, it’s because you’ve succeeded at solving all the problems in the way. Kind of tautological.

If you don’t, it’s because some problem came up that you didn’t know how to solve, or predicted (consciously or not) would be too painful or frustrating or tiring to solve… which are themselves problems that could be hypothetically solved, but if we don’t know how, or we predict that solving them would be too painful or frustrating, then etc, etc.

Our brains seek rewards, and one of our reward functions involves showing competence and solving problems. When we get stuck on a problem, rather than try to brute-force it (Time consuming! Tiring! Unpleasant!), most people have natural defense-mechanisms pop up that will divert our brain’s attention elsewhere. Better to stop expending resources on something that will not reward you and try to focus on other things that will, right?

This mental pop-out is really important for avoiding getting mentally stuck in problems, and is likely a big part of what makes human cognition “special.” A lot of humanity’s problem solving capabilities exist through abstract thinking, but you can get stuck in abstract thinking much more easily than in reality. You can also get your attention hijacked by things that aren’t “real.” Minds facing discomfort or difficulty are just acting rationally when seeking more rewarding stimulation.

It’s not our brains’ fault that we’ve aimed them at goals that are totally abstract and disconnected from our immediate survival, nor is it their fault we’ve surrounded them, in the modern world, with superstimuli like social media and video games, such that the more rewarding stimulation we turn to instead of solving our problems are not often developing skills that will solve more problems; they just feel like they do.

But it’s important to notice that this natural impulse isn’t itself bad. Phrases like “diffuse thinking” or “lateral thinking” or “flexible thinking” were invented to point at the way our brains sometimes come up with answers to problems in indirect ways. It’s common advice for people stuck on problems to take a shower or walk or generally just do anything that doesn’t require mental attention, so they can give their subconscious the chance to mix old and new problems and ideas in ways that sometimes lead to unexpected “Eureka!” moments.

Which is why flexible thinking is a part of executive function. Sometimes we get stuck when trying to solve a problem because we’re stuck thinking in a specific way, or have blindspots that keep us from noticing potential solutions or alternatives.

Which is why, if you learn more ways to solve problems, expand your awareness of solution space, you’re empowered to do more things, and you’re less likely to get tripped up and stop when trying to achieve any given goal. Getting caught up in “yak shaving” is generally considered a bad thing, but… well, sometimes in life, changing a lightbulb requires shaving a yak. The more easily you can swap between multiple different tasks in a short time, the less likely you are to be stymied by abruptly different kinds of problem solving that you might be called upon to do.

For some people, interruptions are more difficult to return from than others, and in a word, that sucks. Good organization can help with that, as mentioned above. But getting better at switching between modes of thinking while working on the same problem doesn’t necessarily often have the same derailing effect.

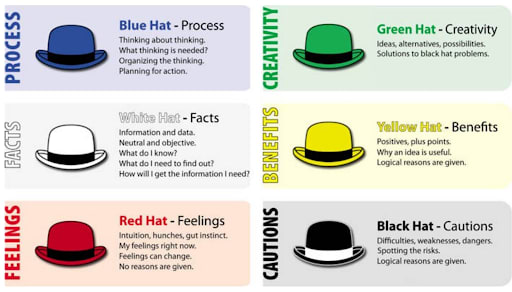

Edward de Bono was a physician and psychologist who wrote a lot (like, a lot) of books on thinking and reasoning more effectively and creatively. He coined the term “lateral thinking,” and one of his many ideas, the Six Thinking Hats, is an example of trying to systematize flexible thinking:

The idea is that you can think through a problem from each of these different lenses, one at a time, to ensure you’re not missing the solution by being too stuck in a particular mental frame. It’s also a particularly useful tool for social coordination, where, instead of people having different hats on at different times and potentially butting heads over why they’re focusing on different aspects of a debated concept or problem or solution, everyone take turns working to make different focuses of attention common knowledge, while being more obviously part of the same team.

(I also happen to think, from an IFS perspective, that whatever helps a group of people coordinate better could also help with an individual trying to coordinate themselves.)

I don’t know how effective Dr. de Bono’s 6 Hats technique is compared to alternatives; there’s some research done that claims effectiveness when used in total[14] or just from trying on particular hats[15], but as with all “rationality techniques,” my main takeaway is people should in general be trying more things (so long as they’re low cost) and see if they work for them, because finding even one out of ten that does can significantly help improve our lives.

TRIZ is a procedure formalized by inventor and sci-fi author Genrich Altshuller, though he was sent to a gulag before he could spread it among Soviet engineers. After Stalin’s death, he was released and founded an engineering school that popularized the method, which is meant to help people reframe specific problems we have to general ones, so we can more easily find general solutions that can then be adapted into specific solutions for the one we face.

It’s the inspiration for not just this pretty cool database that lets you look up all sorts of potential physics problems and solutions, but also some Separation Principles for solving apparent contradictions in design space, and an additional (somewhat intimidating) list of 40 Principles for general problem solving. In his later years, Altshuller believed this system could be used not just for engineering problems, but for overall critical thinking and creative problem solving, and created a community that has continued spreading the good word.

His various intellectual descendants promote it as the all-inclusive method for systematized problem solving, but as with all such things, your mileage may vary. Creative thinking, an as-yet fairly illegible and mysterious process, is likely going to work somewhat differently for everyone, which again is a good reason to experiment.

Which isn’t to say there might not be better and worse systems for it. But personal fit shouldn’t be underestimated, particularly if it means you’re more likely to remember to use the method or schema. Some people use tarot cards, while for others, the Magic: The Gathering color wheel cuts reality at a number of useful joints:

Credit to Duncan Sabien. “Color pentagram” doesn’t roll off the tongue quite as well.

Deep knowledge of this kind of schema can create powerful intuition pumps like “How might MtG Red orient to this,” or “What would MtG Green think of this problem?” This can be particularly useful if you feel a strong affinity for the “opposite” colors of Blue or White, and make some effort to really understand how people who identify with the others see and experience and navigate through the world.

Yes, this is just another way of saying “understanding how other people think is valuable” or “taking on a diversity of viewpoints can help you think better” and similar, which is nothing new, and can be said without the complex “systems.” But if you want to keep yourself from getting stuck thinking in a rigid way, and you want a deliberate mental motion or habit you can build to try, schemas like this can be useful.

The map is not the territory, but the more different maps you collect for reference, the more different lenses you have through which to view reality, the less likely you are to be stuck in any given situation.

Speaking of which, I would be remiss if I didn’t mention therapy. My post on the various different therapy philosophies that all modalities can fit into basically goes over four different lenses through which to view problems and solutions, which can be summarized roughly as:

How our past influences our present (Psychoanalytic)

How incentives shape our behavior (Behaviorist)

How feelings and frames affect our experiences (Existential)

How systems can create/solve our problems (Systemic)

I’d claim that any therapist stuck thinking through problems in just one mode is going to be less effective than one who can consider a problem from multiple, and help guide a client to do so as well. If we expect ourselves to tackle every problem alone, we’re like the therapist who only sticks to one modality, let alone one general philosophy of therapy or theory of change.

But while having a knowledgeable guide is valuable, you don’t need to go to a therapist yourself to learn how to reexamine your problems from different therapeutic lenses. Not just because you can learn them yourself, but also because different people often have very different “natural” ways of viewing problems we face, and those outside views can be just as valuable.

In any case, the more flexible your thinking is, the less likely you are to get stuck on a problem. And the less likely you are to get stuck on a problem, the easier you will find it to work on the next step of it.

Using The “Procedure” in Procedural Executive Function

This series took a while to complete. Part of that is that I lost the original driving motivation to do it once the initial reasons and funding for this research drastically shifted, and I let some of my many other projects take priority.

Of course, noticing difficulty completing a series on executive function is too perfect an opportunity to miss actually putting the research into practice. This meant paying extra attention on the days that I felt were “supposed” to have some time dedicated to working on these articles. Did I work on them as much as I wanted to? If not, why not?

It became practically instinctual to just run down the list and zoom in on what particular thing my brain was tripping over. Thoughts/feelings like “I’d rather be writing fiction/reading/playing video games” soon had an attached thought of “What would make me want to write the next paragraph instead?”

And often I’d just check and read over what I’d gotten to last again, and think something like “Huh, right, I’m stuck because I don’t know how to word this part well. Can I just skip over it and come back? Is there someone I can ask for feedback? How would ChatGPT write it?”

(Still badly, in my view; not technically so, but I’m fairly sensitive to writing voice, and while AI assistance can be useful for writing in other ways, I still feel a need to write from scratch for it to feel even marginally interesting for me to reread.)

Or “Ah, yeah, reading all these research papers has gotten less interesting. What else can I do instead to learn something new related to this?”

(Books like Superlearning by Scott H. Young and A Mind for Numbers by Barbara Oakley were occasionally helpful in pointing in the right directions, even if they didn’t often contain uniquely insightful bits I hadn’t covered already.)

Or “I don’t know how to actually solve this problem, and none of the things I’m looking up are optimistic. I should probably just skip for now and circle back to it, and if I still don’t find anything just say that.”

(This was for Working Memory, which took by far the longest to write and edit to a point where I feel okay with it. I almost just cut out the entire LEGO analogy altogether to reduce bloat and avoid getting the analogy wrong in various ways, but some feedback convinced me to keep it in.)

Since it wasn’t an emotionally complicated or taxing experience, my noticed speed bumps were always of this “knowledge problem” sort. I don’t really experience shame or anxiety or prolonged internal conflict, but these are also common bumps in the road when people are writing something for public consumption, and are why learning to integrate and manage emotional experiences are a powerful deblocker for executive function.

But there are plausibly other things that would come up as well, and I don’t presume that this process will be sufficient on its own to solve everyone’s difficulties with getting something done. I do believe, however, that whatever the solution is, it’s something that can be incorporated into a procedural series similar to this one, and I hope to continue updating and expanding on this series in the future, if some new frame or strong additional component is discovered.

As a final note, I hope you remember the first part of all this: the most important first step in solving executive dysfunction is figuring out if you actually want to do the thing.

Because if you don’t actually want to do it, and you don’t actually need to do it (on a deep, emotionally recognizable level), then the question of “why aren’t I doing this thing?” sort of answers itself.

And you can construct abstract chains of reasoning for why you “should” do it anyway, of course, and those abstract chains of reasoning might evoke aesthetically pleasing values or ethics or philosophies that makes them feel more real and motivating.

But they must tap into some predicted emotional experience that your mind can actually simulate, or they likely won’t motivate you to do “hard” things… including the process of solving problems keeping us from doing what we want, or managing the emotions that rise up when we struggle.

If you dig deep and find out that, yeah, that whole “figure out what I actually want” is the part where you’re stuck...

From my work both as a therapist and teaching at rationality camps and workshops, I can say you’re definitely not alone, there. But that’s another essay, for another time.

Second link is broken.

Should be fixed now, thanks!

One point I want to add to my previous comment:

I think it’s possible that ‘fear of failure + fear of difficulty’ doesn’t fully explain why people struggle to start/continue an action.

In fact, I think there’s a third reason, one that’s fuzzier and therefore perhaps somewhat more delicate to deal with which at least I encounter: I’m often vaguely aware (intuitively/not quite consciously) that a/some second-order consequence(s) will be impacted if I undertake the action, or if I undertake the action before obtaining more information, mustering up sharper focus etc (yes, I realise this is exactly how one might rationalise procrastinating, only about something that isn’t the core object). This is esp true if there’s a general sense of uncertainty about various ramifications of my executing/prioritising/executing in a particular way the action in question.

As context, this is something that’s become true for me in the course of heavy burnout. Quite simply, I lost confidence in my ability to effectively track ALL the things (hypervigilant? Me? What do you mean, overoptimising isn’t optimal?), which caused a bunch of paralysis. I’m working on it; simply becoming aware of these kinds of patterns has helped me tremendously. I think it’s worth recognising the impact such mechanisms can have, at least for people who struggle to trust their focus/discernment, either temporarily like me or possibly chronically, if that’s a thing for really anxious people.

I think there’s a way this failure mode can be rolled into your ‘failure or difficulty’ model, by conceptualising this as a subset of the potential failure or difficulty that may arise if you undertake the action.

I appreciate you writing this sequence. Here’s why:

- I thought the flow of it was pretty smooth (which is helpful when you struggle with EF, obviously) - I esp enjoyed the fact that you maintained a clear enough map of where you were going at a couple of different levels at basically all times.

- I got a lot out of your content, mostly in terms of ‘cool, I now have an easily accessible and pretty intuitive rough structure in mind of what might be going on when I get stuck and which ways the causal arrows point’, which I hadn’t taken the time/didn’t have the bandwidth to figure out/research myself.

- you made connections with frameworks from adjacent fields and examples that spoke to me effortlessly (relevant level of abstraction, etc) and enriched my toolbox.

Thanks esp for the times you shared your personal experiences, offered a bit of your own speculation (I think?) - and pushed through when you struggled to show up to write.