In the previous post, we outlined three phases that students would go through, where each student matriculated through them at their own speed.

Phase 1 was literacy and numeracy.

Phase 2 was core civilizational requirements and survey courses.

Phase 3 was core adulting requirements and self-study.

There are two specific curricula involved in these phases: core civilizational requirements and core adulting requirements.

In this post, we’ll go into more detail about the core civilizational requirements.

Core Civilizational Requirements

What does it mean to live in this day and age?

Where does the material abundance we take for granted come from?

What was life actually like for most of human history, and why is it so much better now?

These are questions that everyone ought to be able to answer, and the fact that most students—and most people, I suspect—can’t is an indictment of our educational system.

The context in which we live and the forces that shape it are core to our understanding of our place in history and the systems, tools, and structures that got us here.

This curriculum draws heavily from the field of progress studies.

We mentioned six classes in the previous post: basic economics, basic statistics, basic industrial history, basic civics/governance, basic scientific method, and basic information (previously media) literacy. We don’t expect this list to be exhaustive, but it’s a good starting point.

Basic Economics

Motivation

I am far from an expert on economics, but I can tell you what supply and demand are, and why they matter. I can talk about the elasticity of supply and demand, and how that generally determines where the burden of a tax falls. I can tell you what price floors and ceilings do to markets.

I can tell you why markets work, and why it matters.

This should not be some kind of elite knowledge. It shouldn’t be hidden behind a college course. It is literally the framework within which our entire economy functions.

This should be taught to every child in every school.

The curriculum will center around this diagram:

There are already plenty of basiceconomicscourses, so it shouldn’t be too difficult to adapt these courses to a level suitable to those in phase 2 (around 10-13). Keep in mind that students are not matriculated by age as well—if they need to be older to grasp these concepts, that’s fine. There’s no need for a whole lot of math—in fact, aside from understanding the graph above, very little math should be needed at all.

In Order To Pass

To pass the course, students will need to take an in-person exam demonstrating understanding of:

Supply, Demand, and the Price Equilibrium

Example response: Supply and demand measure how much of a given good or service is delivered at a given price. The actual price of stuff and amount of stuff made is determined by where the lines meet, where supply = demand.

Why the supply and demand curves slope the way they do

Example response: Supply: the more stuff you produce, the more it costs to make it all, so the price goes up. Demand: people buy less stuff when it’s expensive, and more stuff when it’s cheap.

What elasticity of supply and demand mean

Example response: Elasticity = escape. Elasticity of demand: if people want something but don’t need it, like movie tickets, then they buy less if the price goes up. If they have to buy it though, like a house, than they pay the higher cost. Elasticity of supply: this depends on how much it costs to make one more thing, in addition to what you’re already making. Building another house costs a lot, so it’s got a low elasticity, whereas making another copy of a video game costs very little, so it’s got a high elasticity of supply.

The effects of price floors and ceilings

Example response: A price floor is the lowest price something can be sold at, which is higher than it would be without the floor. This is like the minimum wage, which causes surpluses because there’s more supply than there is demand for it. A price ceiling is the highest price something can be sold at, which is lower than it would be without the ceiling. This is like rent control, which leads to shortages because demand is stuck higher than supply.

Where the burden of a tax falls, and the effects of a tax

Example response: Taxes fall on the people who can’t escape them. If all stuff is taxed when sold, like a sales tax, then people just pay the higher price and the tax falls on consumers. On the other hand, if only one company got taxed, they’d have to pay it because if they didn’t their stuff would be more expensive and people wouldn’t buy it anymore. In general, you get less of whatever you tax, because it makes stuff more expensive and reduces people’s incentive to do stuff.

Why markets beat central planning

Example response: Markets coordinate everybody with bits of knowledge that they all know individually, every day. No matter how smart the central planner is, they’re not smarter than everyone else combined, and they don’t know the specific information that everybody else knows.

Where markets fail

Example response: Markets fail when externalities aren’t priced in, like when a company can just dump waste in a river. That’s where government comes in, to force companies to price in externalities. This is the tragedy of the commons.

Basic Statistics

Motivation

An understanding of probability and risk is crucial, not just to hedge fund managers and poker players, but to everyone in their everyday life. And lack of this understanding underlies some of the most basic logical fallacies and biases in human cognition.

If you check the weather one morning to see that there’s a 50% chance of rain, what does that mean? If you get tested for cancer with a test that has a 2% false positive rate, what are the odds you actually have cancer? What’s the expected value of a lottery ticket, a 401k, or a mortgage?

These question matter for the big decisions in life—everything from your health to what college you decide to go to. Thinking about the future means thinking about probability, which today’s education severely under-equips students to do.

A firm grounding in basic probability and statistics will enable students to make informed decisions about their money, their health, and their future, while equipping them to understand the basics of how data is presented and what it means.

In Order To Pass

To pass the course, students will need to take an in-person exam demonstrating understanding of:

A Frequentist and Bayesian interpretation of probability

Example response: Frequentist: If the weather report says that there’s a 10% chance of rain, then about 1 time out of 10 when I go out I should expect to get rained on. Bayesian: If a cancer test has a 2% false positive rate and it comes up positive for me, that doesn’t mean that I have cancer—it means that the odds of me having cancer have just increased by a factor of 100 / 2 = 50, so I need to take the base rate of me having cancer and multiply it by 50 to find the odds that I have cancer, given the new information.

Compound growth, both of investments and of debt

Example response: If I borrow $1,000 at an interest rate of 5% per year, then the next year I owe $1,000 * 1.05 = $1,050, and the year after I owe $1,050 * 1.05 = $1,102.5, and so on—the amount I owe keeps going up faster. It’s the same way with investments

An understanding of mean, median, and mode

Example response: Mean is everything added up, divided by the number of things, and can be skewed by one thing being really big or really small. Median is when you line up all the things from smallest to biggest and just take the one in the middle. It’s harder to skew. And mode is the most common thing.

An understanding of distributions (normal, power)

Example response: A normal distribution is a bell curve, like height, where most people are in the middle and there’s only a few people that are really short or really tall. A power distribution is like fame, where most people aren’t famous but a few people are really really famous.

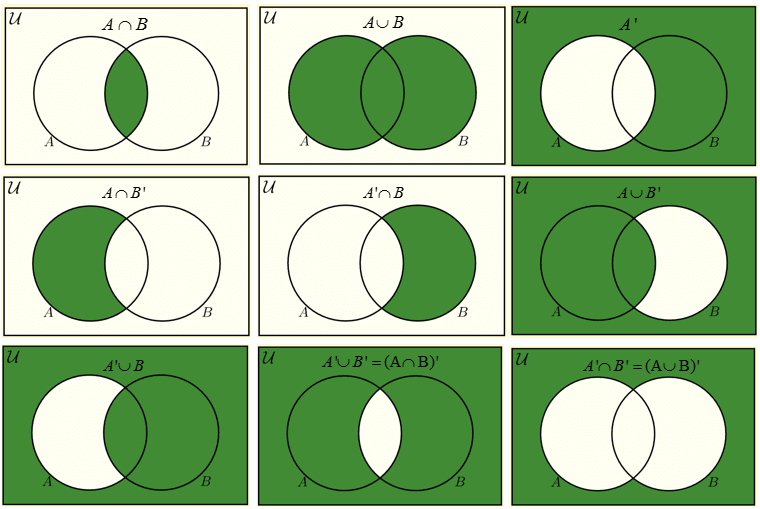

An understanding of “and” vs “or” and “not” in probability

Example response: Whenever you add more propositions with an “and”, you lower the probability, because “and” refers to the intersection of a Venn diagram; the probabilities are multiplied. “Or” usually raises the probability, because you’re including the whole Venn diagram, but you have to be careful not to double count the overlapping part. (Basically the diagram below, but without the need for technical terminology.)

How to do an expected value calculation

Example response: You multiply the chance of something happening by how much you value it happening. So if a lottery ticket costs $1 and it gives a one in a million chance of winning $100,000, then the expected value of the lottery ticket is 10 cents, so you spent a dollar to get back ten cents!

An understanding of how statistics and probability matters in their life, specifically

Example response: In my life, I was thinking about what I wanted to do and thought that maybe I should be a social media influencer, but very few people become social media influencers, it’s a power law distribution, so my odds of becoming one are pretty low. They can make a lot of money, but if you multiply the money they make by the odds of becoming one you get a low number, so it’s got a low expected value.

Basic Industrial History

Motivation

History is a difficult subject to teach, much less design a curriculum for.

Not only are there thousands of years of material to cover, from all over the globe, there’s a multitude of perspectives and lenses to apply to every one of those years.

The task of designing a curriculum is made easier by the fact that we’re designing a mandatory curriculum—that is, a class that everyone is compelled to take and pass. We can therefore restrict ourselves to the history that we feel everyone needs to know.

An American student, in this day and age, doesn’t need to know about the Aztec empires or the Ming dynasty. They don’t even need to know about the American revolution or the Civil War—when would such knowledge affect them in their daily lives?

What those students do need to know, on the other hand, is how the modern era is different from the rest of human history, and why. They need to understand where the abundance they’ve been born in comes from, and what pillars support our society and way of life.

Failure to understand these topics leads voters and citizens to make poor choices when it comes to taxation, regulation, and governance. It leads to a stark misunderstanding of how wealth is created and distributed, which underscores some of the most heinous regimes ever created in human history.

In Order To Pass

To pass the course, students will need to take an in-person exam demonstrating understanding of:

Core ideas of the industrial revolution, including energy available per capita, precise measurements, and interchangeable parts

Example response: The use of coal, while it had negative environmental effects, allowed humans to harness non-muscle sources of energy at scale for the first time. Combined with precise measurements and interchangeable parts, machines could be designed, made and mass-produced for the first time in human history.

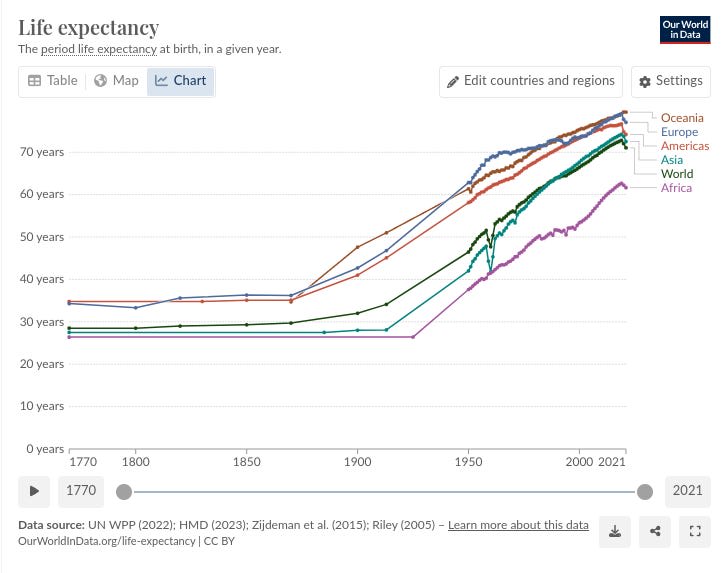

Human life before and after the industrial revolution, in terms of life expectancy, child and mother mortality, etc.

Example response: Before the industrial revolution, there were a small number of elites in every society that had almost all the wealth and everyone else’s lives were poor and short. Afterwards, science and industry massively increased average human lifespan and reduced the number of kids that died.

How capitalism and the corporation, along with private property and governmental protection of rights, enable positive-sum interactions between people

Example response: Corporations allowed multiple people to band together to create organizations that could do more than any of them individually. Capitalism and protection of rights allowed people to invest in the future. Combined, these forces allowed people to build things that would pay off in the future, which helped people generate wealth by creating new sources of wealth.

Example response: You can’t feed a lot of people per acre the way that people were farming a long time ago. People started using bat poop as fertilizer, but there’s only so much bat poop, and they were running out. The Haber-Bosch process was discovered as a response to this, which pulls ammonia out of the atmosphere to make fertilizer, which saved a lot of people from starving.

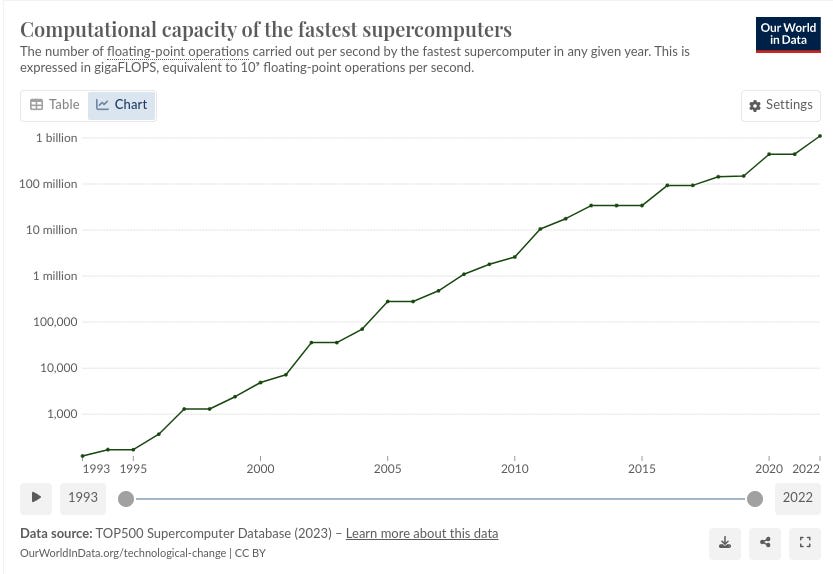

An understanding of the exponential nature of progress, from the industrial revolution to Moore’s Law

Example response: Once there’s a certain amount of progress, you can use that to make even more progress, so progress compounds over time. Moore’s Law, where faster computers are used to build faster computers, is an example of this.

An overview of great human works, from the Panama Canal and the interstate highway system to the Hoover Dam and the space program

Example response: Humanity is awesome! We created a bunch of really cool stuff, like the Panama Canal, which connects the world’s oceans so you don’t have to go all the way around South America. We also put a person on the moon!

Basic Civics/Governance

Motivation

If you’re an American citizen, you get a single vote, same as everyone else. What you choose to do with that vote, on its own, rarely matters—but what everyone does with their votes matters a great deal.

I think a large amount of unrest and unhappiness with the results of our government—not all of it, nor even a majority, but a large portion nonetheless—comes from not understanding how it works. It’s a lot easier to view an elected president as illegitimate when you don’t get how they got elected in the first place.

In Order To Pass

To pass the course, students will need to take an in-person exam demonstrating understanding of:

The three branches of our government, and the division of power between them

Example response: The three branches of government are executive, legislative, and judicial. It’s the legislative branch’s job to write laws, the executive branch’s job to make sure those laws become reality by enforcing them, and the judicial branch’s job to settle problems and disputes and make sure the laws align with our constitution.

The idea of Federalism and the division of power between federal, state, and local governments

Example response: People in the US are governed at the local, state, and federal level. The Federal government handles the big stuff, like war and currency and country-wide regulation. States handle most of the day-to-day laws, like police and small businesses and state-wide regulation. Local governments are often about basic services like water and electricity and road upkeep and land zoning.

How important officials get their jobs

Example response: The president is elected by the states as a whole, senators by everyone in their state, and House members by everyone in their district. Supreme Court judges are selected by the president and approved by the Senate. The cabinet members are selected by the President and confirmed by the Senate.

A history of political parties, the role they play, and both the good and bad they do

Example response: Political parties in America help frame and organize the process of electing officials by vetting and submitting candidates. They tend to aggregate opinions and interests and often care more about opposing their opponents than actually accomplishing anything.

The functioning of the legal system in civil and criminal cases

Example response: In a criminal case, the government prosecutes a person for a crime, and the person is entitled to a lawyer in their defense. Many cases result in plea bargains; those that don’t go to trial, where a judge oversees opposing lawyers arguing about the case before a jury. In a civil case, it’s somebody suing somebody else, and nobody’s entitled to a lawyer. Cases are decided by a judge or jury.

The rights of each citizen

Example response: Everyone has a right to freedom of speech, since it’s one of the rights in the Bill of Rights. This means that people can say what they want, and the government can’t punish them for it. It doesn’t stop them from being fired for it, though, nor does it protect them if they’re directly trying to cause harm.

Basic Scientific Method

Motivation

The word ‘science’ is used to refer to both: a) a methodology for reaching the truth and b) the knowledge accumulated using that methodology.

Understanding what this methodology is, why it’s different from what came before it, and how to use it in every aspect of one’s life is crucial to understanding how humanity has accomplished what it has.

In Order To Pass

To pass the course, students will need to take an in-person exam demonstrating understanding of:

The core of science: Ideas are tested by experiment. Alternatively put: the most effective way to gain true knowledge about the world is to interact with the world.

Example response: You can sit on the couch thinking for as long as you want, but in the end if you want to learn about the world you’ve got to get out there and study it.

How experiments behave differently based on what’s true about the world

Example response: When you design an experiment, you want something that gives different results based on what’s true about reality. For instance, if you wanted to know if two objects of different weights fall at the same rate, you could drop two objects at the same time and observe what happens; if they hit the ground at the same time, they fell at the same rate, otherwise they didn’t.

The scientific process as it currently stands

Example response: Scientists will investigate a hypothesis by gathering data, doing an experiment, and then analyzing the data with statistical methods. It’s tricky to interpret data, but scientists do their best. Then they write a paper outlining what they did and send it to other scientists for peer review. Eventually the paper gets published in a journal.

A probabilistic understanding of evidence, and the difference between evidence and proof

Example response: Evidence makes things more likely, depending on how much you expected to see evidence. Like, since everyone carries a camera in their pocket, then if Bigfoot existed we’d expect someone to get a clear picture by now. Since nobody has, that’s evidence that Bigfoot doesn’t exist. Evidence isn’t proof, though—evidence makes something more or less likely, but proof is definitive.

How making predictions is a better way to test one’s knowledge than trying to explain the past

Example response: If you run an experiment and you don’t make a prediction, then you can just claim that you expected whatever happened and that it means you were right all along. But if you make a public prediction or bet, then you can’t weasel out of it when you’re wrong; you have to face up to how your beliefs don’t match what happened.

Correlation and causality

Example response: Let’s say we find two things together often, like wealth and educational attainment. They correlate. Does that mean that one causes the other? Well, there are a number of different possibilities. If A and B are correlated, then the possibilities are:

A causes B

B causes A

Something else, C, causes both A and B

It’s random chance that they appear together

Basic Information Literacy

Motivation

The information environment people find themselves in today is completely alien to the one evolution prepared us for. It’s completely alien to what people had for almost all of history. It’s almost completely alien to what people had twenty years ago!

Navigating this environment is a key skill, not just to navigate the world in general, but to learning itself. What information can be trusted? What are facts, and what is opinion?

It’s also crucial to prepare children for social media. As much as I would prefer it, I think a doctrine of abstinence from social media would be about as effective as the old-fashioned doctrine of abstinence.

In Order To Pass

To pass the course, students will need to take an in-person exam demonstrating understanding of:

Facts vs. Opinions

Example response: There are facts, which are true things that happened or verifiable aspects of the world, and then there are how people feel about those facts, which are opinions. Facts aren’t opinions, and opinions aren’t facts.

How the map is not the territory

Example response: There is a difference between what people believe and what is true. Sometimes they’re the same, and sometimes they’re not. Everyone has a bunch of beliefs and models in their head of the world, but those beliefs and models can be wrong. Different people can look at the same territory—real thing in the real world—and come away with different maps—ideas in their heads about it.

How the media is about entertainment, not truth

Example response: The news channels, newspapers, and other sources of news aren’t really rewarded or punished for reporting the actual, bare-bones factual truth. They’re trying to make money like every other business, and so they’re after engagement. They’ll say things just to get clicks and likes regardless of whether or not it’s true. That doesn’t mean the media always lies, just that they don’t always tell the truth, either.

How social media distorts the truth

Example response: When you post on social media, you only post the stuff that makes you look good. Other people do that too. That means that when you look at someone on social media whose life looks awesome, you’re only seeing the highlights, not their actual life. Similarly, when you see a bunch of people doing better than you, that’s okay—their apparent success doesn’t mean that you’re any worse off.

How to research a topic

Example response: Say that I want to learn more about something, like moss. I can search for it with Google or another search engine, read about it on Wikipedia, or ask an LLM about it. It’s a good idea to check some of these information sources against each other, in case some of them are wrong, which they’ll sometimes be, especially if the topic is controversial.

How to change their own minds

Example response: It’s natural that, as you learn more information, you change your mind about things. That’s good! You should always be open to changing your mind, because it’s always possible that you’re wrong. If you never change your mind at all, you don’t react to new information—which means you might as well be a rock, not a person. People change, rocks don’t.

Conclusion

The above should not be considered a complete list—six bullet points do not equal a curriculum—but should convey the general ideas students are to learn about each topic, along with a vague sense of the level of understanding expected at the students’ ages when they take these courses.

To stress a point made in the introduction, the goal of phase 2 is to give students an understanding of the context of the world in which they live—how it functions materially, economically, and politically, and why it functions that way.

Too much of current american education is framed academically—subjects ascended in a particular order, history taught chronologically, etc. This makes sense for someone studying the subjects to attain mastery over them, but mastery is not a reasonable (or even desirable) goal for most students. Instead, phase 2 of this curriculum is geared towards giving students reasonable models for how the world works today. This gives them a way to place themselves and their choices in the context of the modern world.

If they want to further their studies in any of these areas, they are welcome to, but we only require a basic level of understanding.

Let’s Design A School, Part 2.3 School as Education—The Curriculum (Phase 2, Specific)

Link post

In the previous post, we outlined three phases that students would go through, where each student matriculated through them at their own speed.

Phase 1 was literacy and numeracy.

Phase 2 was core civilizational requirements and survey courses.

Phase 3 was core adulting requirements and self-study.

There are two specific curricula involved in these phases: core civilizational requirements and core adulting requirements.

In this post, we’ll go into more detail about the core civilizational requirements.

Core Civilizational Requirements

What does it mean to live in this day and age?

Where does the material abundance we take for granted come from?

What was life actually like for most of human history, and why is it so much better now?

These are questions that everyone ought to be able to answer, and the fact that most students—and most people, I suspect—can’t is an indictment of our educational system.

The context in which we live and the forces that shape it are core to our understanding of our place in history and the systems, tools, and structures that got us here.

This curriculum draws heavily from the field of progress studies.

We mentioned six classes in the previous post: basic economics, basic statistics, basic industrial history, basic civics/governance, basic scientific method, and basic information (previously media) literacy. We don’t expect this list to be exhaustive, but it’s a good starting point.

Basic Economics

Motivation

I am far from an expert on economics, but I can tell you what supply and demand are, and why they matter. I can talk about the elasticity of supply and demand, and how that generally determines where the burden of a tax falls. I can tell you what price floors and ceilings do to markets.

I can tell you why markets work, and why it matters.

This should not be some kind of elite knowledge. It shouldn’t be hidden behind a college course. It is literally the framework within which our entire economy functions.

This should be taught to every child in every school.

The curriculum will center around this diagram:

There are already plenty of basic economics courses, so it shouldn’t be too difficult to adapt these courses to a level suitable to those in phase 2 (around 10-13). Keep in mind that students are not matriculated by age as well—if they need to be older to grasp these concepts, that’s fine. There’s no need for a whole lot of math—in fact, aside from understanding the graph above, very little math should be needed at all.

In Order To Pass

To pass the course, students will need to take an in-person exam demonstrating understanding of:

Supply, Demand, and the Price Equilibrium

Example response: Supply and demand measure how much of a given good or service is delivered at a given price. The actual price of stuff and amount of stuff made is determined by where the lines meet, where supply = demand.

Why the supply and demand curves slope the way they do

Example response: Supply: the more stuff you produce, the more it costs to make it all, so the price goes up. Demand: people buy less stuff when it’s expensive, and more stuff when it’s cheap.

What elasticity of supply and demand mean

Example response: Elasticity = escape. Elasticity of demand: if people want something but don’t need it, like movie tickets, then they buy less if the price goes up. If they have to buy it though, like a house, than they pay the higher cost. Elasticity of supply: this depends on how much it costs to make one more thing, in addition to what you’re already making. Building another house costs a lot, so it’s got a low elasticity, whereas making another copy of a video game costs very little, so it’s got a high elasticity of supply.

The effects of price floors and ceilings

Example response: A price floor is the lowest price something can be sold at, which is higher than it would be without the floor. This is like the minimum wage, which causes surpluses because there’s more supply than there is demand for it. A price ceiling is the highest price something can be sold at, which is lower than it would be without the ceiling. This is like rent control, which leads to shortages because demand is stuck higher than supply.

Where the burden of a tax falls, and the effects of a tax

Example response: Taxes fall on the people who can’t escape them. If all stuff is taxed when sold, like a sales tax, then people just pay the higher price and the tax falls on consumers. On the other hand, if only one company got taxed, they’d have to pay it because if they didn’t their stuff would be more expensive and people wouldn’t buy it anymore. In general, you get less of whatever you tax, because it makes stuff more expensive and reduces people’s incentive to do stuff.

Why markets beat central planning

Example response: Markets coordinate everybody with bits of knowledge that they all know individually, every day. No matter how smart the central planner is, they’re not smarter than everyone else combined, and they don’t know the specific information that everybody else knows.

Where markets fail

Example response: Markets fail when externalities aren’t priced in, like when a company can just dump waste in a river. That’s where government comes in, to force companies to price in externalities. This is the tragedy of the commons.

Basic Statistics

Motivation

An understanding of probability and risk is crucial, not just to hedge fund managers and poker players, but to everyone in their everyday life. And lack of this understanding underlies some of the most basic logical fallacies and biases in human cognition.

If you check the weather one morning to see that there’s a 50% chance of rain, what does that mean? If you get tested for cancer with a test that has a 2% false positive rate, what are the odds you actually have cancer? What’s the expected value of a lottery ticket, a 401k, or a mortgage?

These question matter for the big decisions in life—everything from your health to what college you decide to go to. Thinking about the future means thinking about probability, which today’s education severely under-equips students to do.

A firm grounding in basic probability and statistics will enable students to make informed decisions about their money, their health, and their future, while equipping them to understand the basics of how data is presented and what it means.

In Order To Pass

To pass the course, students will need to take an in-person exam demonstrating understanding of:

A Frequentist and Bayesian interpretation of probability

Example response: Frequentist: If the weather report says that there’s a 10% chance of rain, then about 1 time out of 10 when I go out I should expect to get rained on. Bayesian: If a cancer test has a 2% false positive rate and it comes up positive for me, that doesn’t mean that I have cancer—it means that the odds of me having cancer have just increased by a factor of 100 / 2 = 50, so I need to take the base rate of me having cancer and multiply it by 50 to find the odds that I have cancer, given the new information.

Compound growth, both of investments and of debt

Example response: If I borrow $1,000 at an interest rate of 5% per year, then the next year I owe $1,000 * 1.05 = $1,050, and the year after I owe $1,050 * 1.05 = $1,102.5, and so on—the amount I owe keeps going up faster. It’s the same way with investments

An understanding of mean, median, and mode

Example response: Mean is everything added up, divided by the number of things, and can be skewed by one thing being really big or really small. Median is when you line up all the things from smallest to biggest and just take the one in the middle. It’s harder to skew. And mode is the most common thing.

An understanding of distributions (normal, power)

Example response: A normal distribution is a bell curve, like height, where most people are in the middle and there’s only a few people that are really short or really tall. A power distribution is like fame, where most people aren’t famous but a few people are really really famous.

An understanding of “and” vs “or” and “not” in probability

Example response: Whenever you add more propositions with an “and”, you lower the probability, because “and” refers to the intersection of a Venn diagram; the probabilities are multiplied. “Or” usually raises the probability, because you’re including the whole Venn diagram, but you have to be careful not to double count the overlapping part. (Basically the diagram below, but without the need for technical terminology.)

How to do an expected value calculation

Example response: You multiply the chance of something happening by how much you value it happening. So if a lottery ticket costs $1 and it gives a one in a million chance of winning $100,000, then the expected value of the lottery ticket is 10 cents, so you spent a dollar to get back ten cents!

An understanding of how statistics and probability matters in their life, specifically

Example response: In my life, I was thinking about what I wanted to do and thought that maybe I should be a social media influencer, but very few people become social media influencers, it’s a power law distribution, so my odds of becoming one are pretty low. They can make a lot of money, but if you multiply the money they make by the odds of becoming one you get a low number, so it’s got a low expected value.

Basic Industrial History

Motivation

History is a difficult subject to teach, much less design a curriculum for.

Not only are there thousands of years of material to cover, from all over the globe, there’s a multitude of perspectives and lenses to apply to every one of those years.

The task of designing a curriculum is made easier by the fact that we’re designing a mandatory curriculum—that is, a class that everyone is compelled to take and pass. We can therefore restrict ourselves to the history that we feel everyone needs to know.

An American student, in this day and age, doesn’t need to know about the Aztec empires or the Ming dynasty. They don’t even need to know about the American revolution or the Civil War—when would such knowledge affect them in their daily lives?

What those students do need to know, on the other hand, is how the modern era is different from the rest of human history, and why. They need to understand where the abundance they’ve been born in comes from, and what pillars support our society and way of life.

Failure to understand these topics leads voters and citizens to make poor choices when it comes to taxation, regulation, and governance. It leads to a stark misunderstanding of how wealth is created and distributed, which underscores some of the most heinous regimes ever created in human history.

In Order To Pass

To pass the course, students will need to take an in-person exam demonstrating understanding of:

Core ideas of the industrial revolution, including energy available per capita, precise measurements, and interchangeable parts

Example response: The use of coal, while it had negative environmental effects, allowed humans to harness non-muscle sources of energy at scale for the first time. Combined with precise measurements and interchangeable parts, machines could be designed, made and mass-produced for the first time in human history.

Human life before and after the industrial revolution, in terms of life expectancy, child and mother mortality, etc.

Example response: Before the industrial revolution, there were a small number of elites in every society that had almost all the wealth and everyone else’s lives were poor and short. Afterwards, science and industry massively increased average human lifespan and reduced the number of kids that died.

How capitalism and the corporation, along with private property and governmental protection of rights, enable positive-sum interactions between people

Example response: Corporations allowed multiple people to band together to create organizations that could do more than any of them individually. Capitalism and protection of rights allowed people to invest in the future. Combined, these forces allowed people to build things that would pay off in the future, which helped people generate wealth by creating new sources of wealth.

How humanity has solved dire problems in the past, including the polio vaccine, the green revolution, the Haber-Bosch process, the hole in the ozone layer, acid rain, and so on

Example response: You can’t feed a lot of people per acre the way that people were farming a long time ago. People started using bat poop as fertilizer, but there’s only so much bat poop, and they were running out. The Haber-Bosch process was discovered as a response to this, which pulls ammonia out of the atmosphere to make fertilizer, which saved a lot of people from starving.

An understanding of the exponential nature of progress, from the industrial revolution to Moore’s Law

Example response: Once there’s a certain amount of progress, you can use that to make even more progress, so progress compounds over time. Moore’s Law, where faster computers are used to build faster computers, is an example of this.

An overview of great human works, from the Panama Canal and the interstate highway system to the Hoover Dam and the space program

Example response: Humanity is awesome! We created a bunch of really cool stuff, like the Panama Canal, which connects the world’s oceans so you don’t have to go all the way around South America. We also put a person on the moon!

Basic Civics/Governance

Motivation

If you’re an American citizen, you get a single vote, same as everyone else. What you choose to do with that vote, on its own, rarely matters—but what everyone does with their votes matters a great deal.

I think a large amount of unrest and unhappiness with the results of our government—not all of it, nor even a majority, but a large portion nonetheless—comes from not understanding how it works. It’s a lot easier to view an elected president as illegitimate when you don’t get how they got elected in the first place.

In Order To Pass

To pass the course, students will need to take an in-person exam demonstrating understanding of:

The three branches of our government, and the division of power between them

Example response: The three branches of government are executive, legislative, and judicial. It’s the legislative branch’s job to write laws, the executive branch’s job to make sure those laws become reality by enforcing them, and the judicial branch’s job to settle problems and disputes and make sure the laws align with our constitution.

The idea of Federalism and the division of power between federal, state, and local governments

Example response: People in the US are governed at the local, state, and federal level. The Federal government handles the big stuff, like war and currency and country-wide regulation. States handle most of the day-to-day laws, like police and small businesses and state-wide regulation. Local governments are often about basic services like water and electricity and road upkeep and land zoning.

How important officials get their jobs

Example response: The president is elected by the states as a whole, senators by everyone in their state, and House members by everyone in their district. Supreme Court judges are selected by the president and approved by the Senate. The cabinet members are selected by the President and confirmed by the Senate.

A history of political parties, the role they play, and both the good and bad they do

Example response: Political parties in America help frame and organize the process of electing officials by vetting and submitting candidates. They tend to aggregate opinions and interests and often care more about opposing their opponents than actually accomplishing anything.

The functioning of the legal system in civil and criminal cases

Example response: In a criminal case, the government prosecutes a person for a crime, and the person is entitled to a lawyer in their defense. Many cases result in plea bargains; those that don’t go to trial, where a judge oversees opposing lawyers arguing about the case before a jury. In a civil case, it’s somebody suing somebody else, and nobody’s entitled to a lawyer. Cases are decided by a judge or jury.

The rights of each citizen

Example response: Everyone has a right to freedom of speech, since it’s one of the rights in the Bill of Rights. This means that people can say what they want, and the government can’t punish them for it. It doesn’t stop them from being fired for it, though, nor does it protect them if they’re directly trying to cause harm.

Basic Scientific Method

Motivation

The word ‘science’ is used to refer to both: a) a methodology for reaching the truth and b) the knowledge accumulated using that methodology.

Understanding what this methodology is, why it’s different from what came before it, and how to use it in every aspect of one’s life is crucial to understanding how humanity has accomplished what it has.

In Order To Pass

To pass the course, students will need to take an in-person exam demonstrating understanding of:

The core of science: Ideas are tested by experiment. Alternatively put: the most effective way to gain true knowledge about the world is to interact with the world.

Example response: You can sit on the couch thinking for as long as you want, but in the end if you want to learn about the world you’ve got to get out there and study it.

How experiments behave differently based on what’s true about the world

Example response: When you design an experiment, you want something that gives different results based on what’s true about reality. For instance, if you wanted to know if two objects of different weights fall at the same rate, you could drop two objects at the same time and observe what happens; if they hit the ground at the same time, they fell at the same rate, otherwise they didn’t.

The scientific process as it currently stands

Example response: Scientists will investigate a hypothesis by gathering data, doing an experiment, and then analyzing the data with statistical methods. It’s tricky to interpret data, but scientists do their best. Then they write a paper outlining what they did and send it to other scientists for peer review. Eventually the paper gets published in a journal.

A probabilistic understanding of evidence, and the difference between evidence and proof

Example response: Evidence makes things more likely, depending on how much you expected to see evidence. Like, since everyone carries a camera in their pocket, then if Bigfoot existed we’d expect someone to get a clear picture by now. Since nobody has, that’s evidence that Bigfoot doesn’t exist. Evidence isn’t proof, though—evidence makes something more or less likely, but proof is definitive.

How making predictions is a better way to test one’s knowledge than trying to explain the past

Example response: If you run an experiment and you don’t make a prediction, then you can just claim that you expected whatever happened and that it means you were right all along. But if you make a public prediction or bet, then you can’t weasel out of it when you’re wrong; you have to face up to how your beliefs don’t match what happened.

Correlation and causality

Example response: Let’s say we find two things together often, like wealth and educational attainment. They correlate. Does that mean that one causes the other? Well, there are a number of different possibilities. If A and B are correlated, then the possibilities are:

A causes B

B causes A

Something else, C, causes both A and B

It’s random chance that they appear together

Basic Information Literacy

Motivation

The information environment people find themselves in today is completely alien to the one evolution prepared us for. It’s completely alien to what people had for almost all of history. It’s almost completely alien to what people had twenty years ago!

Navigating this environment is a key skill, not just to navigate the world in general, but to learning itself. What information can be trusted? What are facts, and what is opinion?

It’s also crucial to prepare children for social media. As much as I would prefer it, I think a doctrine of abstinence from social media would be about as effective as the old-fashioned doctrine of abstinence.

In Order To Pass

To pass the course, students will need to take an in-person exam demonstrating understanding of:

Facts vs. Opinions

Example response: There are facts, which are true things that happened or verifiable aspects of the world, and then there are how people feel about those facts, which are opinions. Facts aren’t opinions, and opinions aren’t facts.

How the map is not the territory

Example response: There is a difference between what people believe and what is true. Sometimes they’re the same, and sometimes they’re not. Everyone has a bunch of beliefs and models in their head of the world, but those beliefs and models can be wrong. Different people can look at the same territory—real thing in the real world—and come away with different maps—ideas in their heads about it.

How the media is about entertainment, not truth

Example response: The news channels, newspapers, and other sources of news aren’t really rewarded or punished for reporting the actual, bare-bones factual truth. They’re trying to make money like every other business, and so they’re after engagement. They’ll say things just to get clicks and likes regardless of whether or not it’s true. That doesn’t mean the media always lies, just that they don’t always tell the truth, either.

How social media distorts the truth

Example response: When you post on social media, you only post the stuff that makes you look good. Other people do that too. That means that when you look at someone on social media whose life looks awesome, you’re only seeing the highlights, not their actual life. Similarly, when you see a bunch of people doing better than you, that’s okay—their apparent success doesn’t mean that you’re any worse off.

How to research a topic

Example response: Say that I want to learn more about something, like moss. I can search for it with Google or another search engine, read about it on Wikipedia, or ask an LLM about it. It’s a good idea to check some of these information sources against each other, in case some of them are wrong, which they’ll sometimes be, especially if the topic is controversial.

How to change their own minds

Example response: It’s natural that, as you learn more information, you change your mind about things. That’s good! You should always be open to changing your mind, because it’s always possible that you’re wrong. If you never change your mind at all, you don’t react to new information—which means you might as well be a rock, not a person. People change, rocks don’t.

Conclusion

The above should not be considered a complete list—six bullet points do not equal a curriculum—but should convey the general ideas students are to learn about each topic, along with a vague sense of the level of understanding expected at the students’ ages when they take these courses.

To stress a point made in the introduction, the goal of phase 2 is to give students an understanding of the context of the world in which they live—how it functions materially, economically, and politically, and why it functions that way.

Too much of current american education is framed academically—subjects ascended in a particular order, history taught chronologically, etc. This makes sense for someone studying the subjects to attain mastery over them, but mastery is not a reasonable (or even desirable) goal for most students. Instead, phase 2 of this curriculum is geared towards giving students reasonable models for how the world works today. This gives them a way to place themselves and their choices in the context of the modern world.

If they want to further their studies in any of these areas, they are welcome to, but we only require a basic level of understanding.