Hell is wasted on the evil

Chuck Palahniuk is an author like no other. Consider his second-most-popular book Choke.

Victor Mancini, a medical-school dropout, is an antihero for our deranged times. Needing to pay elder care for his mother, Victor has devised an ingenious scam: he pretends to choke on pieces of food while dining in upscale restaurants. He then allows himself to be “saved” by fellow patrons who, feeling responsible for Victor’s life, go on to send checks to support him. When he’s not pulling this stunt, Victor cruises sexual addiction recovery workshops for action, visits his addled mom, and spends his days working at a colonial theme park.

―from the summary of Choke by Chuck Palahniuk

Some authors write to entertain. Others write to educate. I want my reader to shout “What the fuck did I just read‽”

Fight Club is Chuch Palahniuk’s cleanest and least happy book. This is not a coincidence. A common theme running through Palahniuk’s works is the idea that extreme happiness and extreme suffering are two sides of the same coin. When editors compelled him to tone down the horrors in Fight Club, they sucked the happiness out of it too.

When I take vacations, I don’t go anywhere nice. I don’t make myself comfortable. My vacations tend to be desperate struggles for survival in the impoverished sectors of awful technodystopias like China. Or—you know—just desperate struggles for survival in the wilderness.

When I was 19 I took a Greyhound to Las Vegas. I earned enough money performing street magic to buy food at Panda Express. While I was there, a man offered to buy me dinner with his family. I turned it down because I didn’t want to accept charity. Only later did it occur to me that I must have been the most interesting person he met in Las Vegas and that buying my stories for the price of a hamburger would be a steal compared to the alternative entertainment offerings.

Stories are about suffering. A good novelist tortures her characters. I know many software engineers (and other technicians) who were excited about their jobs in college and in their early 20s. I was jealous of them back then. Now, in their late 20s, my friends realize they are living in the Matrix.

On my imaginary bookshelf, beside the complete works of Chuck Palahniuk, is Goblin Slayer.

Every goblin had a weapon in hand, and all of them were bent on Priestess standing just outside the entrance…

“O Earth Mother, abounding in mercy, by the power of the land, grant safety to we who are weak.”

And suddenly the goblins found themselves slamming their heads against an invisible wall and rolling back into the fortress. A wall of holy power blocking the entrance and preventing the goblins’ escape. The Earth Mother, abounding in mercy, had shielded her devout follower with the miracle of Protection.

“GORRR?!”

“GARRR?!”

The goblins grew increasingly panicked as they realized they’d been trapped. They screeched and cried as they beat their clubs and their fists against the invisible barrier and found nothing could break it. Smoke and flames slowly obscured the goblins, until they vanished from sight.

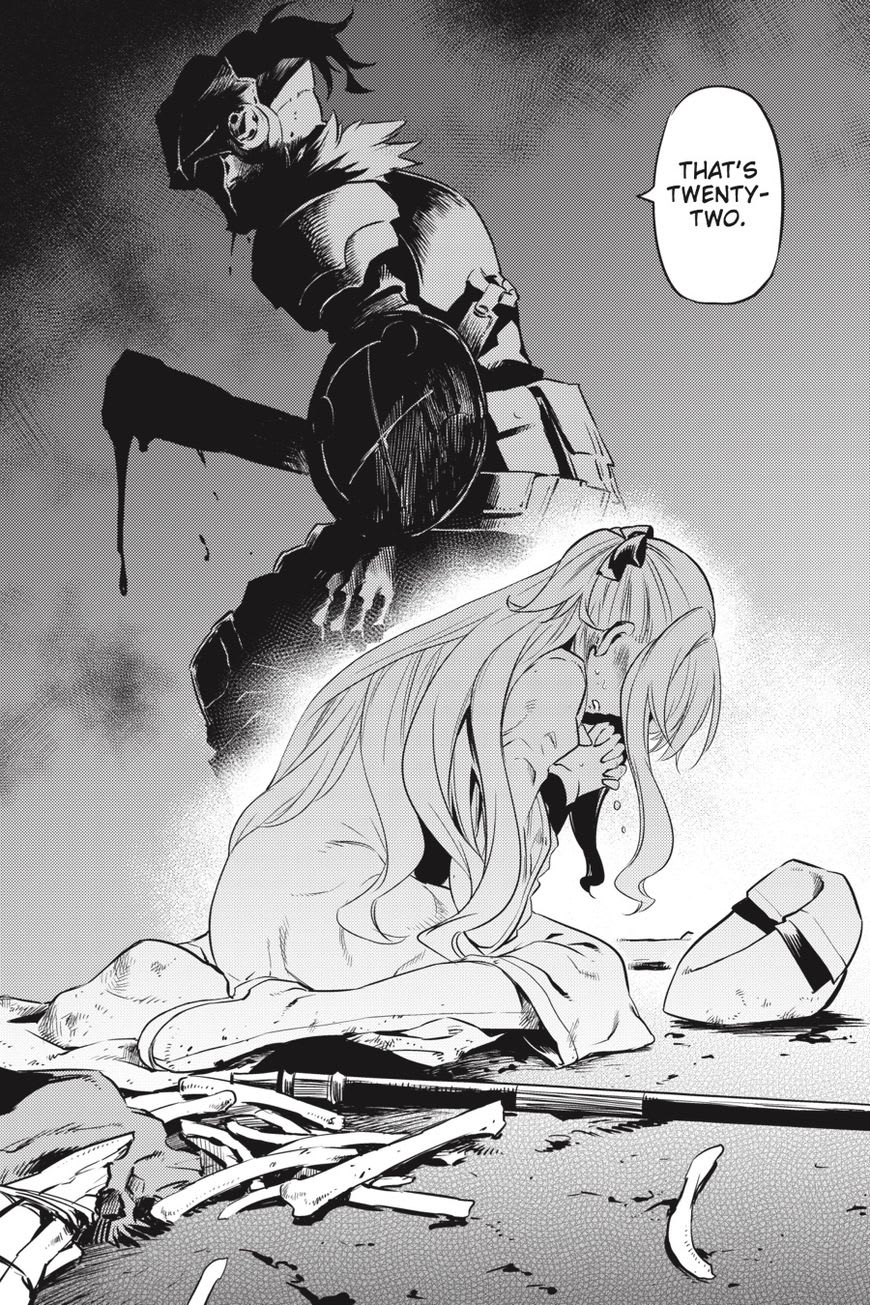

“I’d heard you’d been given a new miracle,” Goblin Slayer said, casually shooting an arrow into a goblin trying to escape the area. “Six. It made our job much easier.”

“But…to use Protection like this…,” Priestess said. Her voice was hoarse, and it wasn’t from breathing the smoke that rose from the once-living goblins.

⋮

The mountain fortress burned.

With that, the village below was saved from the threat of goblins. The souls of those departed adventurers could each go into the arms of whatever god they had believed in.

The bodies of the goblins burned. The bodies of the adventurers burned. And the body of the kidnapped girl burned as the smoke drifted into the sky.

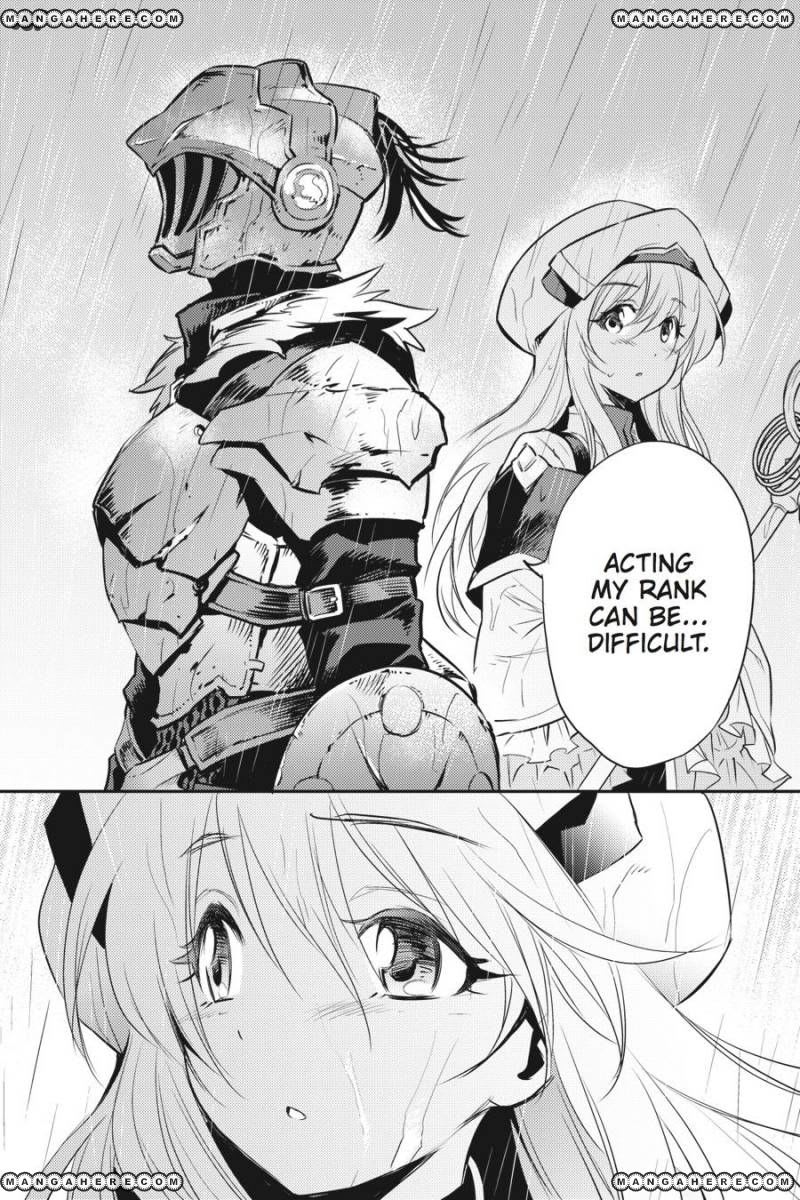

“We’ll have to control the blaze. When it’s burned out, we’ll need to look for any survivors and deal with them,” Goblin Slayer said, looking up at the smoke, without a trace of emotion in his voice. There was a pause. “…Acting my rank can be…difficult.”

Priestess watched him as though seeing something heartbreaking. There was no way she could know his expression under that helmet. Or there shouldn’t have been.

Almost unconsciously, she joined her hands, knelt down, and prayed.

The heat and smoke covered the sky in dark clouds, and at length, a black rain began to fall. She prayed as the raindrops fell on her, as her vestments became streaked with ash.

The only thing she wanted was salvation.

Salvation for whom and from what she did not know.

―Goblin Slayer Volume 1

Cynicism is fear, doubt and disbelief. The opposites of cynicism are courage, optimism and faith. Cynics are cowards.

Children tend to be courageous, optimistic and believing. It is rare (and sad) to find a cynical child. Cynicism is an adult trait. For most people, cynicism seems to increase as they get older. Courage, optimism and belief get worn away by harsh reality. Except…belief only gets worn away by reality if you believe untrue things. If you believe true things then your faith gets stronger over time as evidence confirms it.

If you pretend to be a good person so others will reward you and you don’t get rewarded then you will become cynical. If you always attempt to do good because you like to do good then you can never become cynical. When one method fails to do good you just attempt another method. A good person seeks out opportunities to do good with the desperation of a castaway in the desert seeking out water. They will find it or die trying. You do not stop being thirsty just because water is scarce. The opposite is true. Hell is wasted on the evil.

- Awakening by (May 30, 2024, 7:03 AM; 123 points)

- Ukraine Situation Report 2022/03/04 by (Mar 5, 2022, 6:44 AM; 71 points)

- This War of Mine by (Sep 25, 2021, 1:43 AM; 64 points)

- [Letter] Advice for High School #2 by (Apr 30, 2021, 8:42 AM; 38 points)

- 's comment on Let’s Rename Ourselves The “Metacognitive Movement” by (Apr 27, 2021, 4:21 PM; 19 points)

- 's comment on The Machine that Broke My Heart by (Dec 30, 2021, 1:38 PM; 6 points)

- 's comment on Anger by (Apr 19, 2021, 6:30 AM; 5 points)

Are opportunities to do good in such short supply?

No.

This is my favorite exchange I have ever read on LessWrong.

Opportunities to do the most good are.

I guess it’s necessary to get a bit technical to explain what I mean by that. I do not mean that the number of maximally-good things is small; that is true, but will be true in most environments.

What I mean is that the distribution has a crazy variance (possibly no finite variance); take two “opportunities to do good” and compare them to each other, and an orders-of-magnitude difference is not rare.

The water-in-the-desert analogy really falls apart at that point. It’s more like an investor looking for a good startup to invest in; successful startups aren’t that rare, but the quality varies immensely; you’d much much much prefer to invest in “the next Google/Uber/etc” rather than the next [insert some company from 2010 which made a good profit but which you and I have never heard of].

If I’m reading this correctly, then generally we’re seeing a rather flat payoff curve over most “do good opportunities” and the rare max should stand out like a sore thumb when taking a good look. So those really should be things do-gooders will jump on quickly. (Note, that doesn’t mean they are done quickly or that additional assistance is not important.)

While not as obvious, it probably also means that a lot of more mundane opportunities are getting ignored. That comes from an insight offered in one of my classes from years back asking why so much clumping (think fad type stuff here) exists when the marginal utility of the consumed good is pretty much equal to all the other goods that could have been consumer. In other words, when the opportunity cost is zero why is everyone doing the same thing?

I suspect we could see something like that in the “do good” space. Therefore, taking the path not followed could be a very good thing.

Do you mean the differences between the expected utility upfront? Or do you mean the differences between the actual utility in the end (which the actor might have no way to accurately predict in advance)?

I reject the principled distinction. To me, it’s more of a spectrum.

You believe untrue things because people told you to believe untrue things, for their own purposes. Arriving at a set of true beliefs in isolation from society isn’t really an option.

I’m not a native speaker, can someone please explain the meaning of “Hell is wasted on the evil” in simpler terms?

If you value doing good, then your values will be satisfied better by living in a horrible world than a utopia.

Fixed. Thanks.

Seems related:

https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/kJrpCJshBoaY6YS4L/overconfidence?commentId=BEBA9Mr3PgnLZTvnx

How does a person who keeps trying to do good but fails and ends up making things worse fit into this framework?

In my experience, there’s two main cases of “trying to do good but fails and ends up making things worse”.

You try halfheartedly and then give up. This happens when you don’t care much about doing good.

You do something in the name of good but don’t look too closely at the details and end up doing harm.

#2 is particularly endemic in politics. The typical political actor puts barely any effort into figuring out if what they’re advocating for is actually good policy. This isn’t a bug. It’s by design.

If you believe you attempt to do good because you truly like to do good, you’re either a saint or you don’t really know yourself well. Could be either, but I know which way I’d bet it.

Why do you think that?

Normal humans have a fairly limited set of true desires, the sort of things we see on Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. Food, safety, sex, belonging, esteem, etc. If you’ve become so committed to your moral goals that they override your innate desires, you are (for lack of a better word) a saint. But for most people, morality is a proxy goal that we pursue as a strategy to reach our true goals. Most people act a culturally specified version of morality to gain esteem and all that goes with it (jobs, mates, friends, etc).

Your true desires won’t change much over your lifetime, but your strategies will change as you learn. For example, I’m a lot less intellectual than I was 30 years ago. Back then I was under the delusion that reading a 600-page book on quantum mechanics or social policy would somehow help me in life; I have since learned that it really doesn’t.

Clearly I’m what the OP would call a cynic, but it misunderstands us. I’m a disbeliever, sure, but not a coward. I know well that peculiar feeling you get just before you screw up your life to do the right thing, and a coward wouldn’t. I just no longer see much value in it. As Machiavelli said, “he who neglects what is done for what ought to be done, sooner effects his ruin than his preservation.”

The true test of a saint is this—if doing the right thing would lead to lifelong misery for you and your family, would you still do it?

This seems to be based on a false dichotomy: “Either I genuinely want to do good AT ANY AND ALL COSTS, or all my attempts to do good are insincere.”

I would argue that there are other possibilities besides those two. A person can genuinely desire to do good because he truly likes to do good, but he has other likes and goals as well and will sometimes sacrifice one goal for the other.

Fair enough, but I’d still say that most people do “good” (by which they mostly mean culturally approved things) as a strategy to achieve some more basic end. In support of this proposition, I’ll note that “good” is defined by different people in different ways that all generally correlate with cultural approval in common cases but strongly diverge in matters of basic principle. See Scott Alexander’s: The Tails Coming Apart as Metaphor for Life.