What causes us to sometimes try harder? I play chess once in a while, and I’ve noticed that sometimes I play half heartedly and end up losing. However, sometimes, I simply tell myself that I will try harder and end up doing really well. What’s stopping me from trying hard all the time?

Alexander

Wonderful, thank you!

Bad question, but curious why it’s called “mechanistic”?

Let me try to apply this approach to my views on economic progress.

To do that, I would look at the evidence in favour of economic progress being a moral imperative (e.g. improvements in wellbeing) and against it (development of powerful military technologies), and then make a level-headed assessment that’s proportional to the evidence.

It takes a lot of effort to keep my beliefs proportional to the evidence, but no one said rationality is easy.

Do you notice your beliefs changing overtime to match whatever is most self-serving? I know that some of you enlightened LessWrong folks have already overcome your biases and biological propensities, but I notice that I haven’t.

Four years ago, I was a poor university student struggling to make ends meet. I didn’t have a high paying job lined up at the time, and I was very uncertain about the future. My beliefs were somewhat anti-big-business and anti-economic-growth.

However, now that I have a decent job, which I’m performing well at, my views have shifted towards pro-economic-growth. I notice myself finding Tyler Cowen’s argument that economic growth is a moral imperative quite compelling because it justifies my current context.

Amazing. I look forward to getting myself a copy 😄

Will the Sequences Highlights become available in print on Amazon?

Have you come across the work of Yann LeCun on world models? LeCun is very interested in generality. He calls generality the “dark matter of intelligence”. He thinks that to achieve a high degree of generality, the agent needs to construct world models.

Insects have highly simplified world models, and that could be part of the explanation for the high degree of generality exhibited by insects. For example, the fact the male Jewel Beetle fell in love with beer bottles mistaking them for females is strong evidence that beetles have highly simplified world models.

I see what you mean now. I like the example of insects. They certainly do have an extremely high degree of generality despite their very low level of intelligence.

Oh, I’m not making the argument that randomly permuting the Rubik’s Cube will always solve it in a finite time, but that it might. I think it has a better chance of solving it than the chicken. The chicken might get lucky and knock the Rubik’s Cube off the edge of a cliff and it might rotate by accident, but other than that, the chicken isn’t going to do much work on solving it in the first place. Meanwhile, randomly permuting might solve it (or might not solve it in the worst case). I just think that random permutations have a higher chance of solving it than the chicken, but I can’t formally prove that.

We can demonstrate this wth a test.

Get a Rubik’s Cube playing robotic arm, and ask it to flip a shuffled Rubik’s Cube randomly until it’s solved. How many years will it take until it’s solved? It’s some finite time, right? Millions of year? Billions of years?

Get a chicken and give it a Rubik’s Cube and ask it to solve it. I don’t think it will perform better than our random robot above.

I just think that randomness is a useful benchmark for performance on accomplishing tasks.

I imagine the relationship differently. I imagine a relationship between how well a system can perform a task and the number of tasks the same system can accomplish.

Does a chicken have a general intelligence? A chicken can perform a wide range of tasks with low performance, and performs most tasks worse than random. For example, could a chicken solve a Rubik’s Cube? I think it would perform worse than random.

Generality to me seems like an aggregation of many specialised processes working together seamlessly to achieve a wide variety of tasks. Where do humans sit on my scale? I think we are pretty far along the x axis, but not too far up the y axis.

For your orthogonality thesis to be right, you have to demonstrate the existence of a system that’s very far along the x axis but exactly zero on the y axis. I argue that such a system is equivalent to a system that sits at zero in both the x and y axes, and hence we have a counterexample.

Imagine a general intelligence (e.g. a human) with damage to a certain specialised part of their brain, e.g. short-term memory. They will have the ability to do a very wide variety of tasks, but they will struggle to play chess.

Jeff Dean has proposed a new approach to ML he calls System Pathways in which we connect many ML models together such that when one model learns, it can share its learnings with other models so that the aggregate system can be used to achieve a wide variety of tasks.

This would reduce duplicate learning. Sometimes two specialised models end up learning the same thing, but when those models are connected together, we only need to do the learning once and then share it.

If Turing Completeness turns out to be all we need to create a general intelligence, then I argue that any entity capable of creating computers is generally intelligent. The only living organism we know of that has succeeded in creating a computer is the humans. Creating computers seems to be some kind of intelligence escape velocity. Once you create computers, you can create more intelligence (and maybe destroy yourself and those around you in the process).

When some people hear the words “economic growth” they imagine factories spewing smoke into the atmosphere:

This is a false image of what economists mean by “economic growth”. Economic growth according to economists is about achieving more with less. It’s about efficiency. It is about using our scarce resources more wisely.

The stoves of the 17th century had an efficiency of only 15%. Meanwhile, the induction cooktops of today achieve an efficiency of 90%. Pre-16th century kings didn’t have toilets, but 54% of humans today have toilets all thanks to economic progress.

Efficiency, if harnessed safely, benefits us all. It means we can get more value for less scarce resources, thus increasing the overall pie.

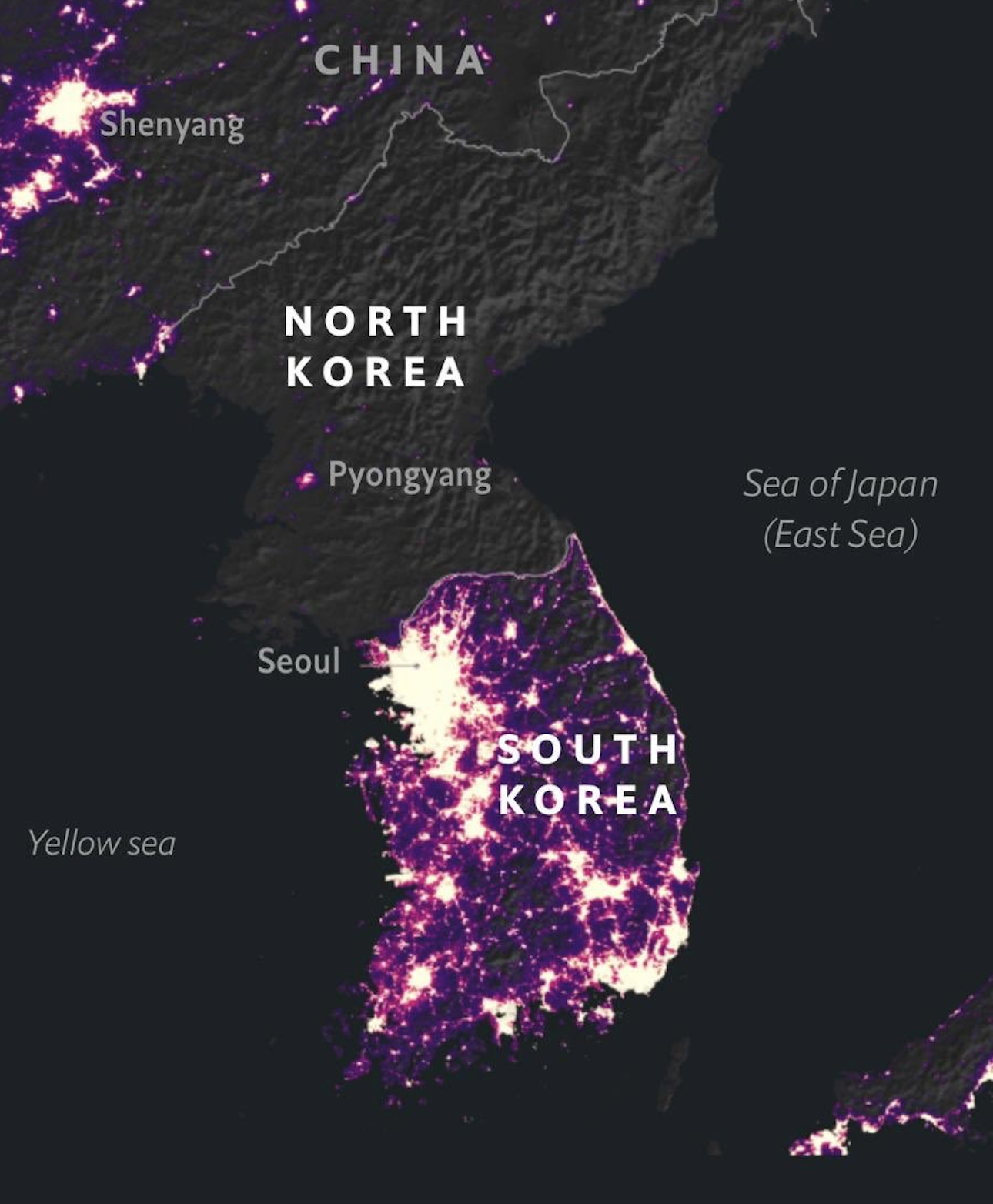

Will economic growth create more inequality due to rent seeking and wealth concentration? The evidence suggests that as GDP (not a perfect measure, but a decent one) grows, per capita incomes also grow. I’d rather be a peasant in South Korea than an average government employee in North Korea.

Hello, I have a question. I hope someone with more knowledge can help me answer it.

There is evidence suggesting that building an AGI requires plenty of computational power (at least early on) and plenty of smart engineers/scientists. The companies with the most computational power are Google, Facebook, Microsoft and Amazon. These same companies also have some of the best engineers and scientists working for them. A recent paper by Yann LeCun titled A Path Towards Autonomous Machine Intelligence suggests that these companies have a vested interest in actually building an AGI. Given these companies want to create an AGI, and given that they have the scarce resources necessary to do so, I conclude that one of these companies is likely to build an AGI.

If we agree that one of these companies is likely to build an AGI, then my question is this: is it most pragmatic for the best alignment researchers to join these companies and work on the alignment problem from the inside? Working alongside people like LeCun and demonstrating to them that alignment is a serious problem and that solving it is in the long-term interest of the company.

Assume that an independent alignment firm like Redwood or Anthropic actually succeeds in building an “alignment framework”. Getting such framework into Facebook and persuading Facebook to actually use it remains to be an unaddressed challenge. Given that people like Chris Olah used to work at Google but left tells me that there is something crucial missing from my model. Could someone please enlighten me?

Additionally, your analogy doesn’t map well to my comment. A more accurate analogy would be to say that active volcanoes are explicit and non-magical (similar to reason), while inactive volcanoes are mysterious and magical (similar to intuitions), when both phenomena have the same underlying physical architecture (rocks and pressure for volcanoes and brains for cognition), but manifest differently.

I just reckon that we are better off working on understanding how the black box actually works under the hood instead of placing arbitrary labels and drawing lines in the sand on things we don’t understand, and then debating those things we don’t understand with verve. Labelling some cognitive activities as reason and others as intuitions doesn’t explain how either phenomenon actually works.

Thanks for your insights Vladimir. I agree that Abstract Algebra, Topology and Real Analysis don’t require much in terms of prerequisites, but I think without sufficient mathematical maturity, these subjects will be rough going. I should’ve made clear that by “Sets and Logic” I didn’t mean a full fledged course on Advanced Set Theory and Logic, but rather simple familiarity with the axiomatic method through books like Naive Set Theory by Halmos and Book of Proof by Hammack.

A map displaying the prerequisites of the areas of mathematics relevant to CS/ML:

A dashed line means this prerequisite is helpful but not a hard requirement.

Almost any technology has the potential to cause harm in the wrong hands, but with [superintelligence], we have the new problem that the wrong hands might belong to the technology itself.

Excerpt from “Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach” by Norvig and Russell.

Source: https://gwern.net/Backstop