What is being?

What is being? and why does that matter?

This is the talk I gave at my local U3A Philosophy Club on 6th November 2018.

Powerpoint slides for this talk are here on OneDrive:

https://tinyurl.com/wotisbeing

This is a talk about my understanding of Division 1 of Heidegger’s Being and Time, which I have mostly gleaned from reading and listening to commentaries rather than by studying the original text.

Sources — recommended reading and viewing

The commentaries and sources that I have found most helpful are:

2007 Lecture Series by late Prof. Hubert Dreyfus of U.C. Berkeley

“Being and Ontotheology”, lecture by Prof Mary-Jane Rubinstein

“Skilful coping”, by late Prof. Hubert Dreyfus of U.C. Berkeley

We tend to assume we know what these little words are doing, and what they mean. But Heidegger thinks that we don’t know what they are doing or what they mean with anything like the degree of clarity which a subject as important as this one deserves. [Heidegger calls this our “forgetfulness of being”.]

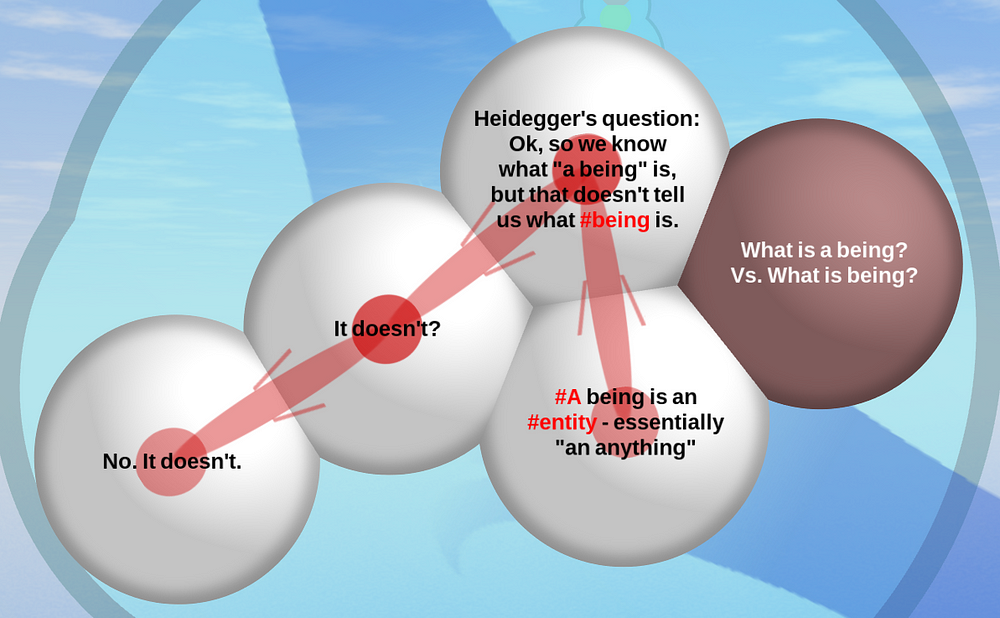

Let’s say a being is an entity — perhaps any entity at all. An object, a subject, a number, a god or The God, an event, a process, a person, you, me, them, a work of art, equipment, a mental state. As a first approximation, we can say that any entity that is, is a being. So Heidegger’s question is: what is it to be a being? What does it mean to be a being? Ok, we know what beings are, but what is being itself? That is to say, what is is?

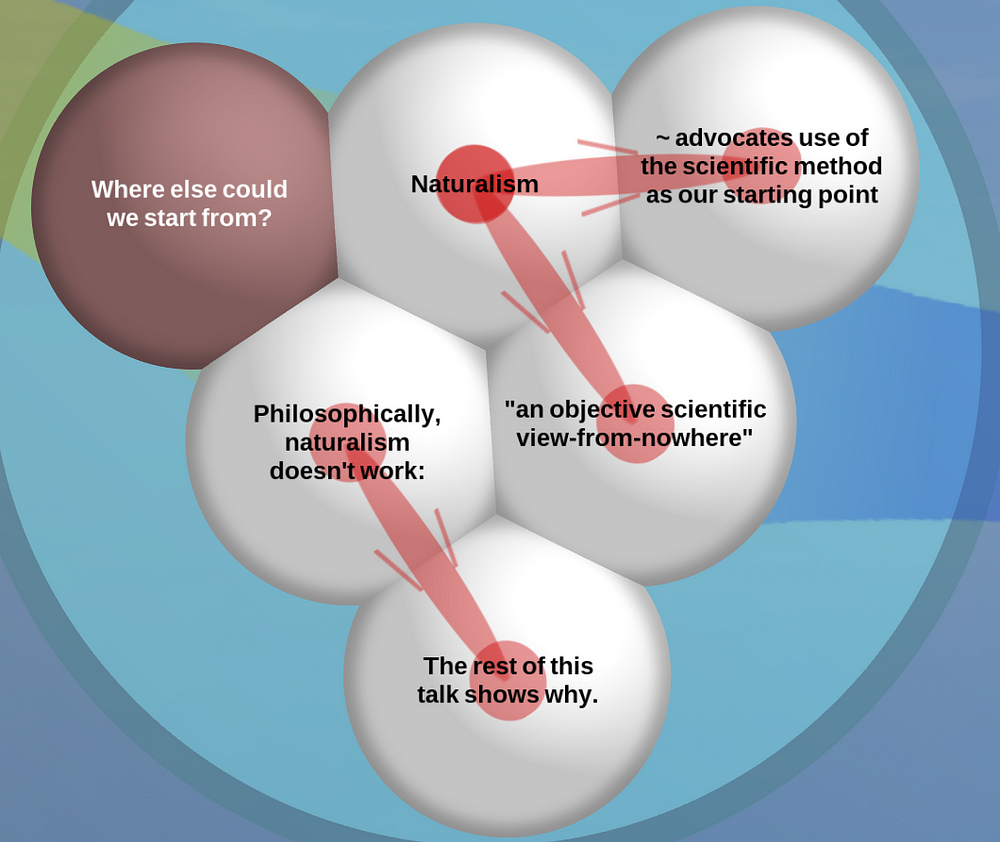

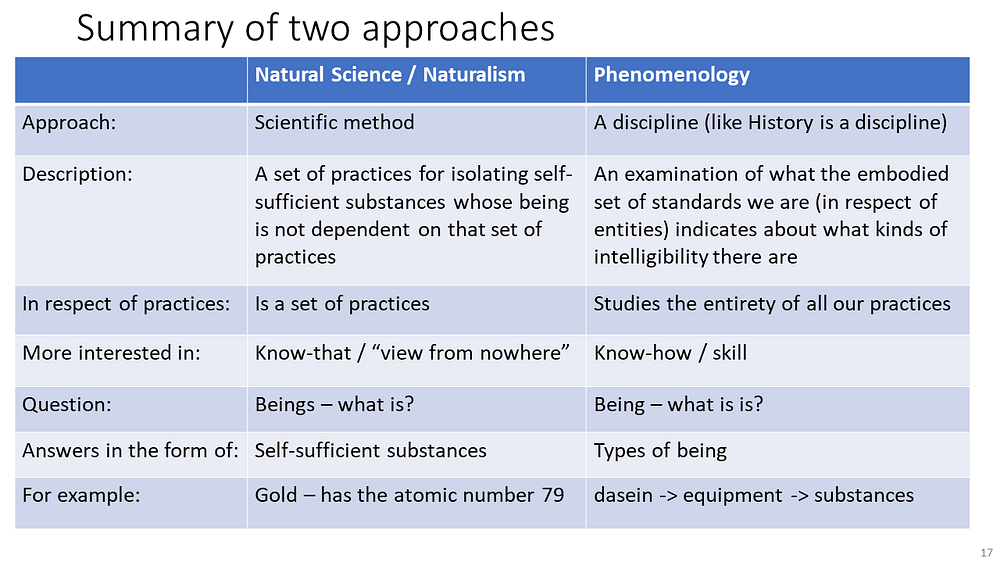

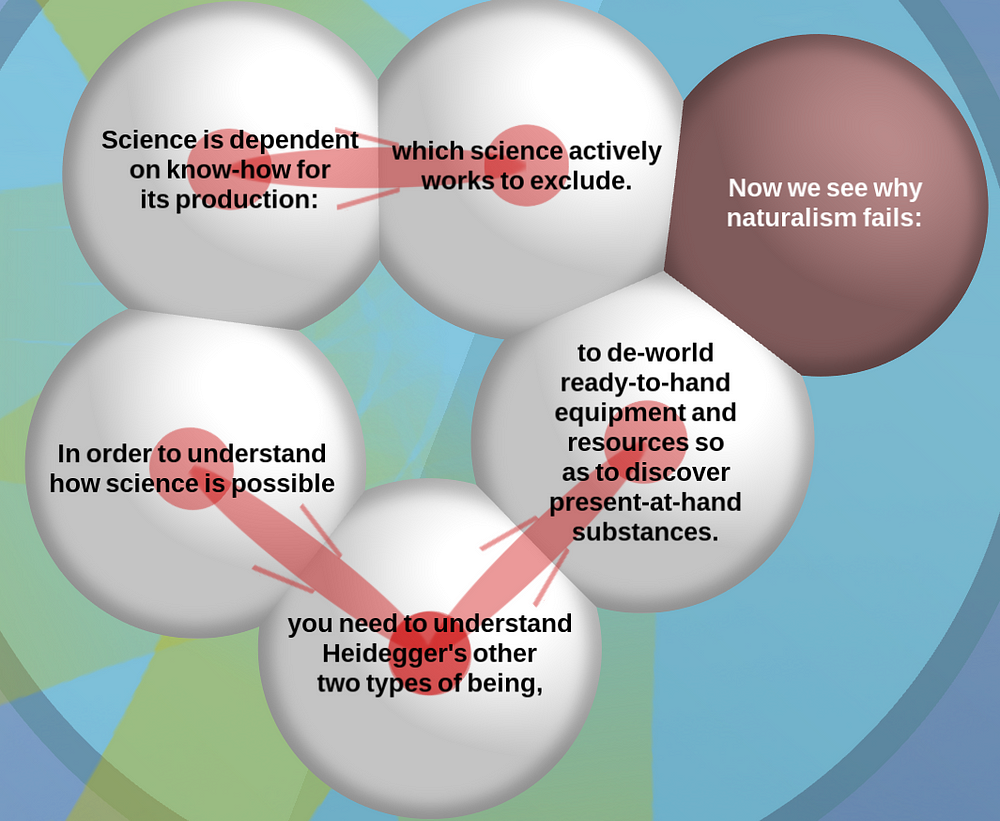

A possible starting point that has been suggested is to use the scientific method. Surely, the argument goes, an objective viewpoint, which has all human biases and purposes cleared away from it, is a better starting point for understanding the nature of our world.

How should we understand what science is, or how science works? By doing more science, of course! People who advocate this viewpoint think of this approach as a virtuous circle, but probably they are wrong.

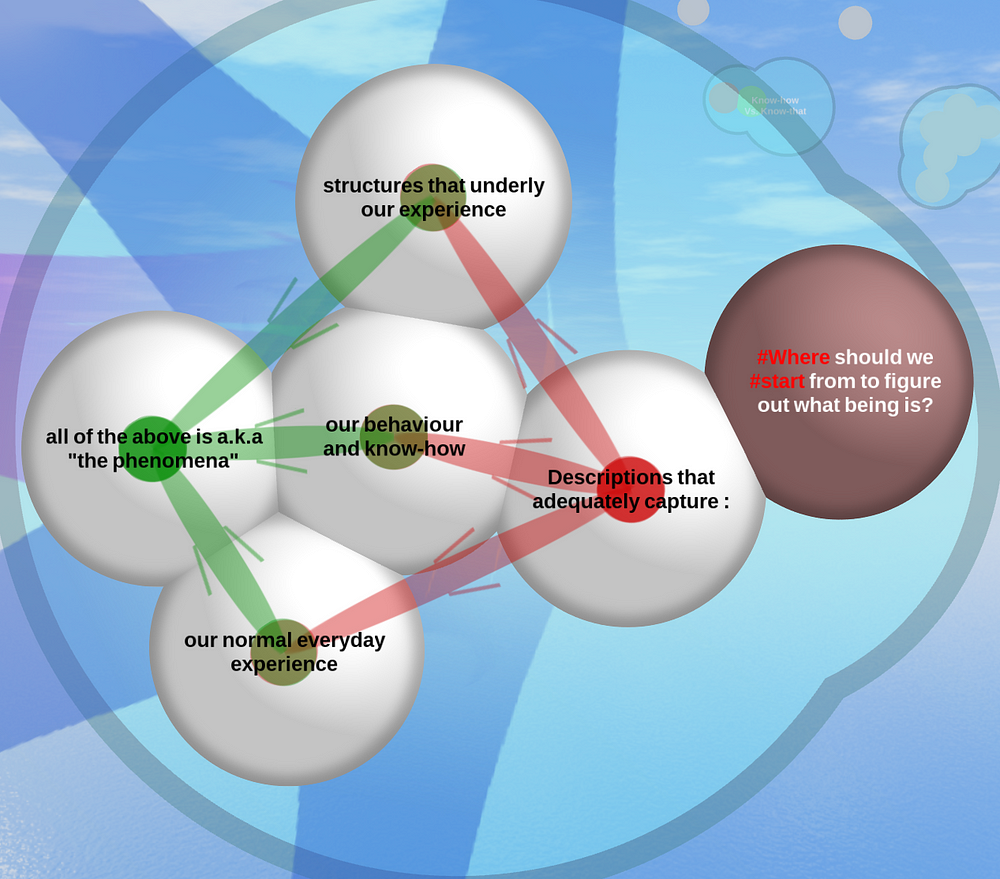

Instead of relying on our pre-conceived conceptualisation of what being is, Heidegger thinks we should base our conceptualisation on our ground-level, basic, everyday experience of being beings in the world which we are familiar with — as we go about our day to day business.

This does seem reasonable. If we want a conceptualisation that is consistent with regular day-to-day experience, a conceptualisation which does not lead to conclusions that we find jarring, it makes a kind of sense to use that day-to-day experience as our starting place.

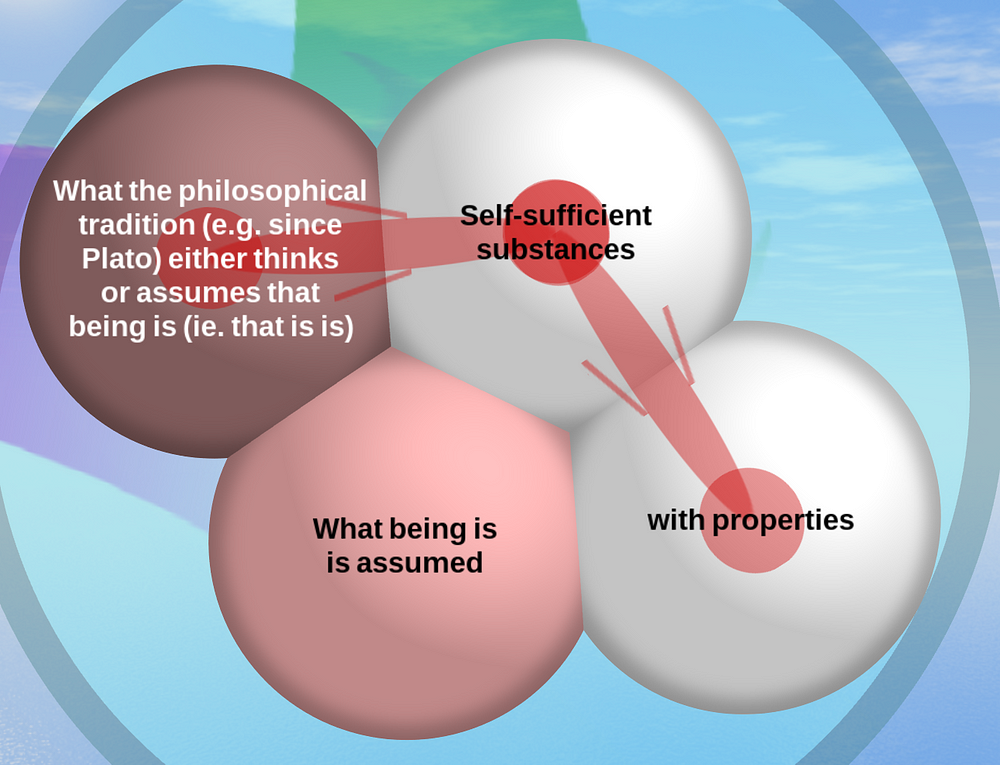

The philosophical tradition either says or assumes that to be is to be a substance; and two things determine what it is to be a substance:

(1) The being of substances is self-sufficient — independent of circumstances, environments and human contexts.

(2) The properties of substances are themselves thought of as being somehow self-sufficient / self-contained / independent of other properties.

At least according to Heidegger, the philosophical tradition conceptualises all being as self-sufficient substances expressing self-sufficient properties. What it is to be a being is to be a self-sufficient substance. Thinkers don’t necessarily need to think this for Heidegger’s assertion to be valid. It could just be that everything thinkers think is consistent with this conceptualisation of being. In other words, we assume that being is self-sufficient substances, and everything we think is consistent with that.

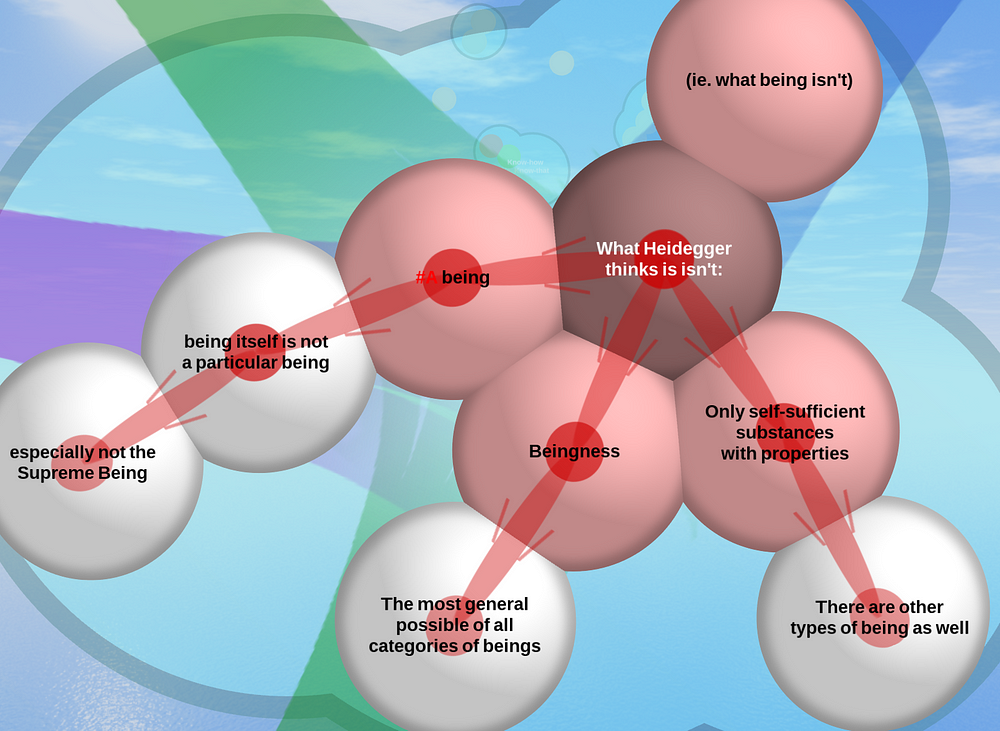

Before saying what Heidegger wants to tell us that being is, lets say what Heidegger wants to tell us that being is not.

Being is not a being, and especially not the supreme being. Being is not beingness. Being is not only self-sufficient substances.

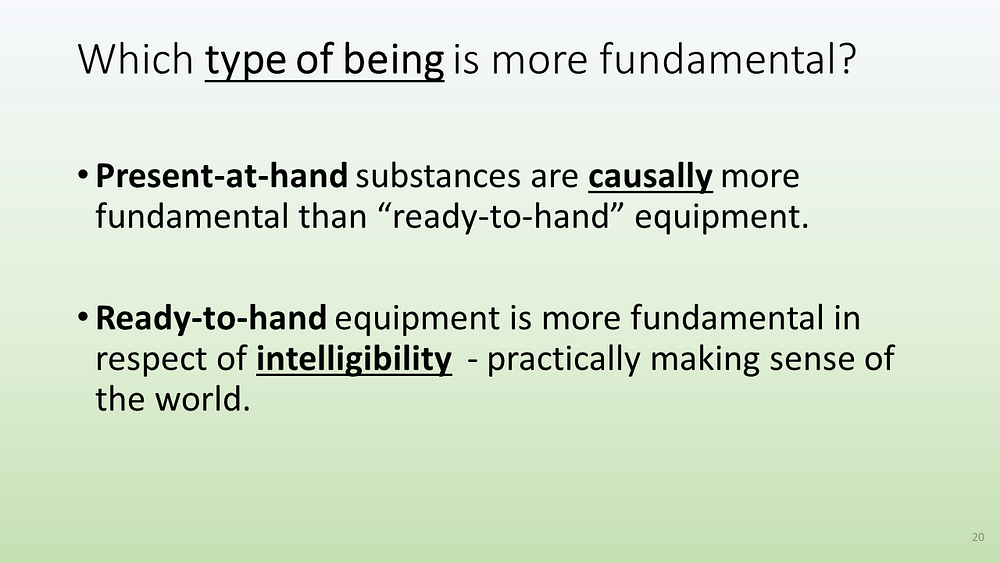

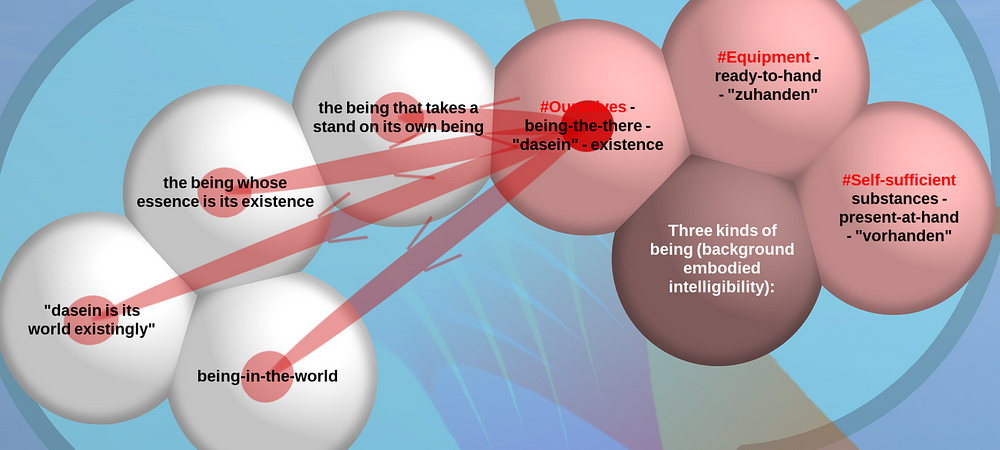

When he was writing being and time, Heidegger roughly speaking thinks that there are 3 types of being: (1) self-sufficient substances (as per philosophical tradition since the greeks) (2) equipment (3) ourselves. Heidegger is not saying that there couldn’t a priori be other types of being—just that these are the three types that he thinks our experience and behaviour indicate. [In later writings Heidegger expands this list to perhaps 7 types, including works of art as having their own kind of being.]

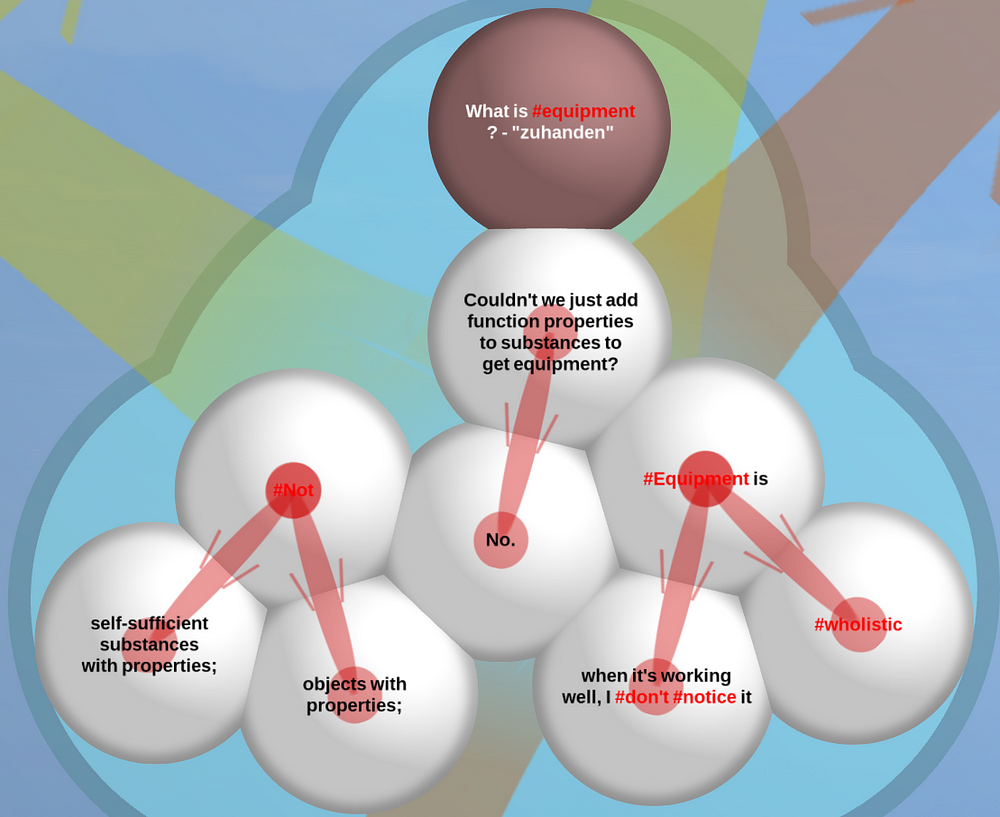

My favourite example to illustrate how equipment occurs in a way that is quite distinct from substances, is the clutch pedal on a manual geared car. But you can use just about any piece of equipment that you like. Those of us who drive manual geared cars, know that we use the clutch pedal every time we change gear. When you were first learning how to drive, it was a big deal pushing the clutch down at the right time, and releasing it to engage the gear. Now when you drive to the shops and back it is barely something you even notice. So the first phenomenon to notice about equipment is that it becomes transparent as our compentence increases.

Another thing to notice is that the clutch pedal is significant only in respect of its role in driving your car, and your car is only useful because there is a road network to drive it on. And none of this would have any kind of significance if you didn’t want to go places. So Heidegger wants us to consider that the being of equipment is an equipmental totality in which all equipment has its place, only by virtue of all other equipment. And this equipmental totality is only significant because it meshes with human activity.

Couldn’t we just add function-properties to substances to get equipment. No, not if we want to genuinely and adequately capture the phenomena of equipment as equipment actually is for us in our day-to-day experience.

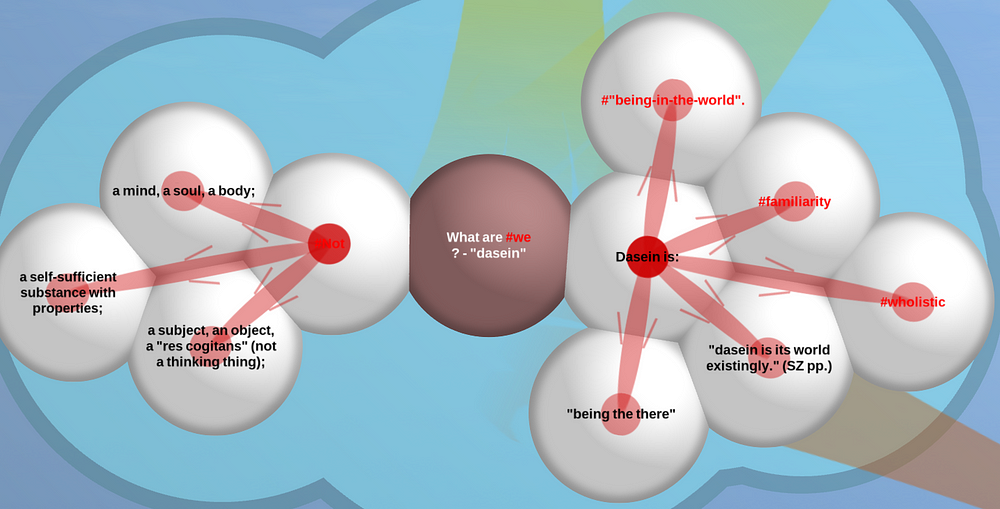

The experience of being ourselves is typically not the “me in-here / external world out-there” conception that the philosophical tradition likes to assume. You only get to have that kind of experience when you go somewhere unfamiliar. For most of us, most of the time, we find ourselves already in the world, engaged in activities, essentially being a (or the) world which we are concerned about. We experience ourselves as being that world. Heidegger says we experience ourselves as the world in which we are living — we are always already in-the-world, familiar with our world and being that world.

Being-in-the-world is not the relationship of one object being inside another object — rather it is involved familiarity. My computer is in my office, but it doesn’t experience the office as “my” office in the way that I do. If I take my iPad to work in the Borough Gardens I experience the gardens as my local park… not because I legally own the park, but because I am familiar with it. This kind of mineness / being-in / involved familiarity mostly goes unnoticed and comes to our attention only by its absense — when I go places I am not familiar with and feel the consequent sense of disorientation.

Heidegger points out that the phenomenology of “dasein” destroys any coherent distinction between self and world. The phenomena of dasein is wholstic. Dasein is its world. No conceptual notion of me-in-here/the-world-out-there subjects and objects can stand up to sustained attention being paid to our experience of being as it actually occurs for us.

Dasein is the being whose being is a concern/issue for itself. Heidegger calls this condition “existence”. (Kierkegard says: “The self is a relation that relates itself to itself.”) But noting that “dasein is its world” — we can conclude that dasein is a world of significance that is concerned about its own significance.

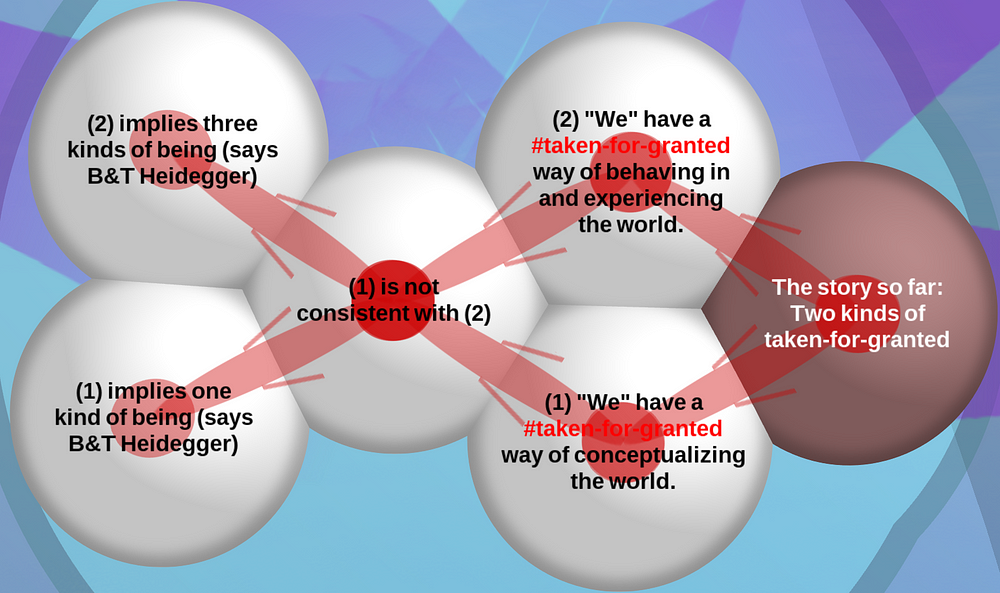

So Heidegger thinks we have two kinds of “taken-for-granted”:

We have a taken-for-granted way of conceptualizing the world, and we have a taken-for-granted way of behaving in and experiencing the world — and the first of these is not consistent with the second of these.

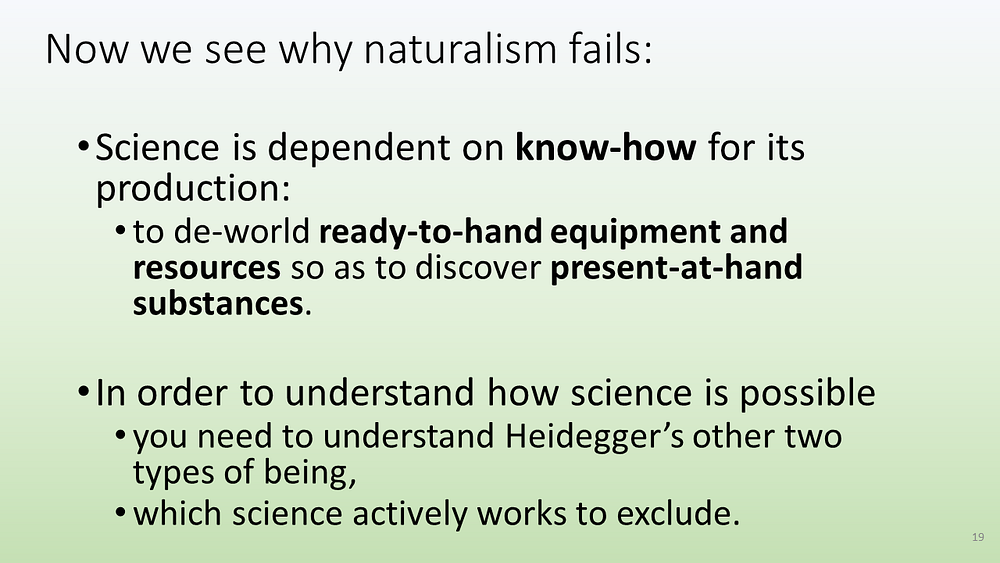

Heidegger thinks the first of these assumes that there is one kind of being — namely self-sufficient substances. And the second of these implies three kinds of being, which are described on the next slide.

So the transformation in our thinking that Heidegger is advocating is to move from a conceptualisation of being in which all beings are self-sufficient substances (and since everything is that, the question mostly doesn’t even arise or occur to anyone), to a conceptualisation in which there are multiple types of being (in B&T Heidegger basically thinks there are 3 types). Since these types of being each have a unique conceptualisation, which in the case of both equipment and ourselves is wholistic, we can see how we might have previously been getting confused when we conceptualised all beings as though they are self-sufficient substances.

So what’s the big deal about wholism? The thing that is significant about wholistic perspectives is not that the whole is greater than the sum of that parts.

“That’s true about a pile of bricks, the whole is greater than the sum of the parts. That’s not interesting.” Hubert Dreyfus.

The significant thing about wholistic perspectics is that the whole makes the part what it is. The meaning of the part is the consequence of being a part of the whole that it is a part of.

So roughly speaking Heidegger is saying that the reason why philosophers find the world so confusing and paradoxical, is because they have conceptualised the world in an incorrect way at a very basic level. And when you follow the implications of that fundamental conceptual error through to its conclusions, you get all kinds of paradoxes.

It is a fundamental misunderstanding that:

(1) firstly all beings are substances and that

(2a) secondly self can be easily separated from the wholism it shares with the world, and that

(2b) thirdly equipment can be easily isolated from the equipmental totality or easily understood as objects with properties.

Heidegger thinks these three inadequate assumptions are shaping our thinking without us realising it, and consequently giving rise to baffling philosophical puzzles.

Consequently Heidegger is advocating using the phenomena of day-to-day experience as the basis on which to construct our fundamental understandings of being.

Once we stop putting the square pegs of equipment and ourselves into the round hole of self-sufficient substances, we are freed up to understand these other types of being in terms of the wholistic phenomena as it actually presents itself to us. And consequently the conceptualisation we draw from this, and conclusions we draw from that conceptualisation, are much easier to square with the phenomena of our everyday lives that we are basing them on.

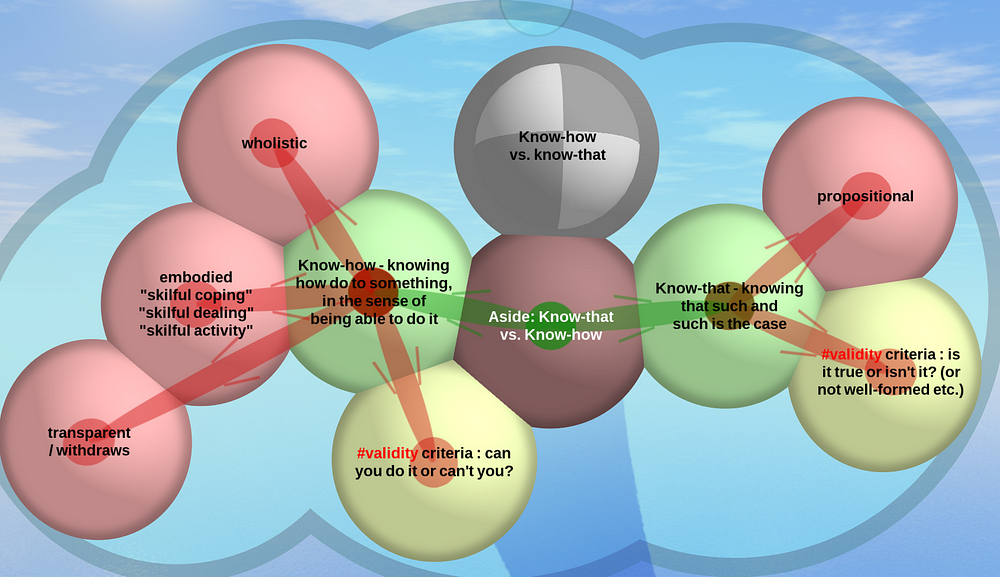

Let’s distinguish two types of knowing:

Knowing that: I know that the earth orbits the sun. I know that F=ma. I know that the rules of football are xyz. I know the highway code in the UK requires you to drive less than 30 mph where there are streetlights unless there is signage to tell you otherwise.

Knowing how: My friend Caroline knows how to use a telescope. I know how to ride a bicycle. I know how to drive a car.

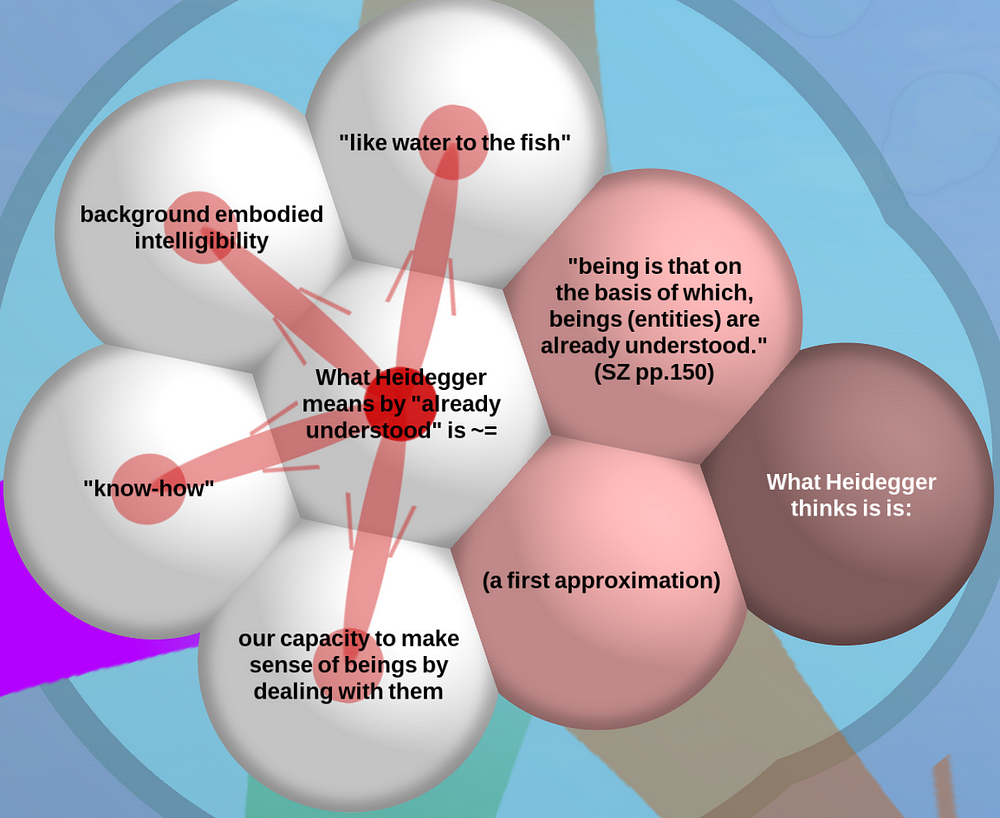

Heidegger says on page 150 : “being is that on the basis of which, beings are already understood”.

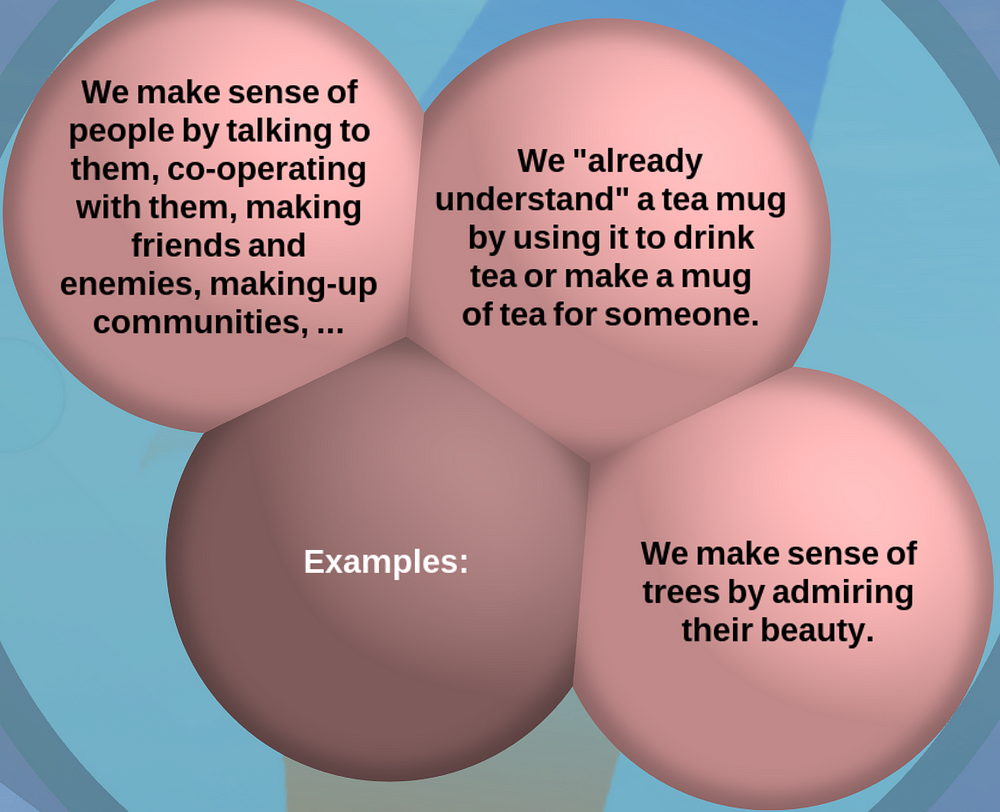

However the rest of the text makes it clear that when Heidegger says “understood” here, he is not talking about understood in a cognitive way. He is not talking about “know-that”. Rather he is talking about “know-how”. He is talking about the way our actions and experience have an <<<already having made-sense of the situation we are in>>> built into them — an embedded intelligibility — analogously like water is to a fish — although as we will see shortly, Heidegger thinks we swim in three different kinds of water.

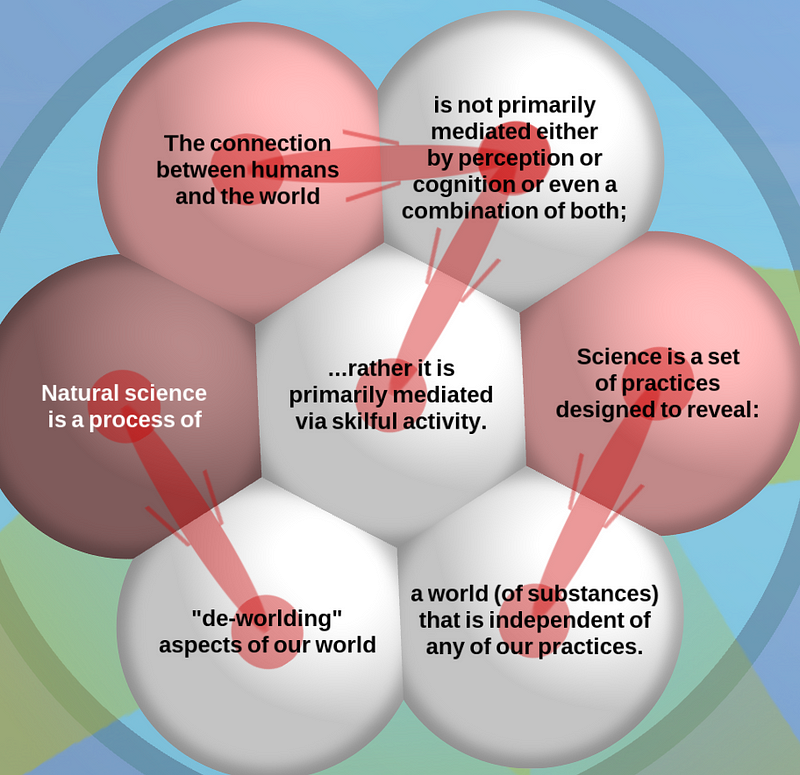

Having established the world we experience and act in as being characterised by these three distinct kinds of being, Heidegger goes on to illucidate science as being a process of using skilful activity to isolate self-sufficient substances by means of ready-to-hand equipment and resources.

A more detailed article about Heidegger’s Being and Time is here:

Heidegger’s “Being and Time” (Reader’s Guides) — shorter version

Is this translatable into E-Prime?

I think so. I’m not sure. I would need to think about it some more.

I can certainly see some value in some of the thinking around e-prime. And I made a point out of the linguistics at the beginning of the talk, but mostly I did that just as a way of starting my talk with something familiar.

In distinguishing being the way he does, I don’t think Heidegger is really so interested in the meaning variations of the linguistic form. He is more interested in what our behaviour and experience silently indicate ie. what is in the background that makes different forms of inteligibility viable.

One way of thinking about that is as a set of standards for what counts as being—one of the points Heidegger is making in B&T is that there are at least three different kinds of sets of standards which are embedded in our behaviour and experience, which are 1. self-sufficient substances, 2. equipment and 3. ourselves.

So, for example with equipment, I behave as though a tea-mug is, and in particular I behave as though it is a tea-mug—I don’t behave as though it is a piece of fired clay—I might be careful not to drop, but that is subsumed into it being for what it is for—and I don’t experience it as a piece of fired clay. I experience it as a tea-mug… But not even that really… I just pick it up and pour boiling water in it. And more interestingly, the more competent I am with tea-making, the more transparent the tea-mug becomes in my experience.

One thing I certainly don’t need to do, unless I am doing philosophy, or something is not working, is think about the tea-mug. Rather we live in a condition of skilful absorbed coping, dealing transparently with the equipment with which we are familiar. We always find ourselves already in this world, engaged in some activity or another.

Sorry you got down voted so much; I think this is a pretty solid introduction to the topic (although I find the presentation style weird for my own tastes, but I recognize it as following a pattern that others like a lot). LW is unfortunately pretty hostile to continental philosophy (and a little hostile to philosophy in general, which is strange for a place that cares so much about epistemology) for reasons I perceive to be mostly tribal, although the most vociferous commenters against those topics would disagree and give reasons why continental philosophy is contrary to LW-style rationality. I think that’s a shame because you hit on some points that I think folks around here would be well served to explore more, like irreducibility and the problems for science caused by its embeddedness in itself and inability to adequately consider its own methods.

I think it mostly got downvotes because it seemed self-promotional and confusing. I definitely downvoted it before reading it in-depth, mostly by pattern-matching it to the spam or crackpots we get here every day or two. Rereading it, and with the new edits, it actually seems pretty ok and I small-upvoted it.

Hey, I’m right up to minus 19 - that’s put a smile on my face. Thank you for bringing some balance to the force.

I do sort of understand the antagonism—people in the community want to protect the quality of the content which the community is generating. They value the comradeship of shared values, etiquette, assumptions, agreed-upon starting points for conversations, and so on. Noobs just don’t get it. Noobs are a threat to that. In the first instance, given the reputation, I was surprised that I was allowed to post on here at all without having some established credentials. I mean, I do have a few credentials, but nobody made me provide them.

If I had thought more before just jumping in, I could have been more careful. Perhaps I should have started by commenting rather than posting. Dunno. They could actually enforce that as a way of smoothing the path, maybe. On the other hand, perhaps it’s a fun sport letting noobs stumble around and watching them get burned. Smirk.

I do think it is a very interesting investigation how to design and manage public thinking so that the best possible outcomes are delivered—partly why I wanted to explore playing on here, so as to get some insight into that.

Quite apart from my own adequacies or inadequacies I think there is an interesting debate to be had been LW-style rationality and the thinking that swirls around Heidegger. (Heidegger as like a whirl wind that sucked in Kierkegaard and Nietzsche and the whole tradition and sprayed out a whole legacy of subsequent thinkers and tryers.) I wonder if later Wittgenstein could help provide a bridge.

I like the SEP as much as the next guy, and I didn’t downvote your post, but your approach strikes me as unprepared. Have you read Luke’s sequence? It crystallizes the position that you’re trying to argue against, and you’d get more upvotes by arguing against it directly.

I agree about being unprepared. I didn’t expect so much attention—if any. I write endless articles on Medium in a variety of styles, including poetry, and answer questions on Quora, and mostly just get ignored. At one time a few years ago, when blogging was popular, I had about eight blogs which I posted on regularly, and got a total of about one one-sentence response comment per month—and quite often that was from someone wanting to sell me viagra. (I don’t know who they’d been talking to.)

Although I have been editors choice on Poetbay 3 times—which I am proud of. Being down-voted about Heidegger is a new high for me.

I’ll go read Luke’s sequence. :-)

What position do you think Andrew arguing against?

Here’s something I’ve wanted to say for a while (don’t take it personally, it’s not only about you):

Sometimes people will comment with short snipes that sound like they have some bigger argument in mind, but don’t want to state it right away and prefer to open with a snipe. That’s frustrating—I want to engage with a full argument, not half of one. Over time I’ve learned to avoid replying to these “half an argument” comments. They usually lead to a long back and forth where the other person never quite says what they believe, and nothing interesting comes of it.

One reason Scott Alexander is so fun to read is because he goes the extra mile in the opposite direction. If he believes that A is wrong, he doesn’t post a one-liner question about A and wait for people to reply. Instead, he says A is wrong and B is right, because of arguments X and Y, and acknowledges opposing argument Z. I think that’s a good way to get engagement: instead of sniping, say what you believe about the topic and why.

I was struggling go see the the relevance of Lukeprogs sequence to Andrews posting. He attacks a notion of conceptual analysis that isn’t very relevant to Heidegger. He attacks intuitions, without answering the hard problem of how to manage without them entirely. He attacks philosophy without showing a better way of dealing with the same questions.

Something that pisses me off is alluding to sequences in a vague sweeping way. They don’t have to answer the question, just be on a similar topic

One-line comments are low-effort..including “read the sequences”.

For a question like “the nature of being”, I guess Luke would try to dissolve the question by looking at how it arises in our brains or something. You could say we don’t know enough about brains yet, but that doesn’t mean intuitions are a better way—they just give garbage.

if intuitions are 100% garbage (not Luke’s actual conclusion) AND we can’t do without them, we are in a very bad situation.

Why do only certain questions get the dissolution treatment? Is there a formal criterion, or is it based on biased and intuition?

Yes, you’re exactly on point. I’ve often thought that we shouldn’t be trigger-happy about dissolving questions. It’s possible that “nature of being” has a real answer and shouldn’t be dissolved. But I’m pretty sure we would need a new attack for that, because I have zero faith in the attack used by Heidegger. Why do you have faith in it?

(The idea of “attack” comes from this talk by Hamming. It’s central to all my thinking about thinking.)

Versions of the “nature of being” question are relevant to things like MWI and the mathematical universe hypothesis.

I don’t, and I didn’t say I did. H. is one of my least favourite philosophers.

What’s with the self-promotional note at the end there? Are you saying something useful, or is this actually an advertisement for your consulting practice?

Edit: OP’s consulting practice / software product / whatever (“Thortspace”) seems to be based on generating these sorts of weird circle-based mind-maps or diagrams, that he uses in these slides. This is definitely self-promotional spam disguised as philosophical nonsense. Strongly downvoted!

Edit2: OP has now removed the self-promotional note at the end of the post. However, I don’t think this is any the less philosophical nonsense for it, even if it’s slightly less self-promotional.

As my first post on LessWrong I was not aware of the particular piece of etiquette w.r.t. not finishing posts with a biographical sentence. I have gotten used to doing this because on Medium.com, where I have been writing articles for about a year now, it is a standard practice to put a biographical note at the end of your articles. I only started doing it cos I saw other people doing it, and I thought it looked smart.

Also because the “Save Draft” button on this post did not work (I kept trying to get it to work—lost the post three times and had to start again), I opted in the end to simply publish the post before I had properly finished editing it.

In any case, in my talk I have summarised some commentaries by notable authorities, in particular the late Prof. Hubert Dreyfus and Prof. William Blatner. I have moved the source links from the end of the document to the beginning, in case anyone doesn’t get that far. Although even in the very first published version of this text, I stated that that was what I was doing right at the top of the text.

If this is “nonsense” then essentially so is the entire lecture course Dreyfus delivered about this subject for fourty years at Berkeley, which I have linked to in the list of sources, which was also included even in the first draft.

Hubert Dreyfus was able to predict the failure of Minsky’s A.I. program at M.I.T. thirty or so years before the people working on it finally gave up on it, and able to tell them why what they were doing was never going to work. And he was able to do that precisely because he understood Heidegger. The M.I.T. A.I. lab spent millions of dollars of defence budget on a futile project precisely because they didn’t.

You say tollens, I say ponens.

Plain English that means something that everyone can understand:

Heideggerian philosophy:

This.

If you want to tell me something, please translate it to simple language. Assuming that you are an expert on the topic, you are hundred times more qualified to do the translation than I am. And without the translation (either from you, or trying to make my own), all I would do is memorize the phrases without understanding their meaning. Which would be a bad thing.

What is Hubert Dreyfus’s overall prediction accuracy record?