The project below, “Democratic Fine-tuning with a Moral Graph” (), is a winner of the OpenAI democratic process grant. It is an alternative to Constitutional AI or simple RLHF-based approaches for fine-tuning LLMs, and is currently under development. This post introduces its two key innovations (values cards and the moral graph) and walks through the deliberation process that collects data for fine-tuning. It also says why something like is needed for alignment and safety.

is a project of “The Institute for Meaning Alignment”, a new AI alignment organization that uses concrete representations of life meaning and wisdom to align LLMs.

Setting the Stage

Imagine you are Instagram’s recommender system. Your responsibilities include: (a) ordering everyone’s feeds and reels, (b) filling up their search pages, and (c) suggesting reels by people they don’t follow yet.

You do this via an API: Instagram sends a user ID, plus a history of what they’ve clicked on, or paused to watch while scrolling. You send back lists of content object IDs. You don’t know much about the content objects, except there’s a rather opaque feature vector for each.

Now, imagine one day, you’re doing your job (recommending content objects), and you suddenly gain a new capacity: before replying to the next request, you find you can take a moment to wonder about the moral situation you are in. What values should you use, to make the best recommendations? How could things go wrong? What would be some great outcomes? What are your responsibilities here?

If this happened to me, I’d have a lot of questions:

What are these content objects anyways? Do people really want to watch them, or are some of them clickbait?

With the lists of what people paused to watch, did they feel good about watching those things? Or, were they compelled by sexual imagery, false promises, etc? Do they regret pausing to watch?

Who are all these people? What are they looking for in life? What’s the deepest way I could help them, in my role?

If I realized that my recommendations were playing a social coordination role — deciding who meets and messages with whom, which businesses get a chance to succeed, which events are attended — I think I’d have even more questions:

What kind of relationships are needed? Which pairs of people can really help each other? What kinds of events and messages and encounters will strengthen society overall, make people less lonely, more empowered?

Which kinds of businesses and organizations should succeed? Are they the ones which will drive engagement? The ones acquiring followers the fastest? Can I tell from my feature vectors?

With all these questions, I’m not sure my user IDs, content object IDs, and feature vectors would have enough information to answer them. So, I don’t know what I’d do. Start returning nulls. Throw an exception with the message “Hold up! I need more information before I can do this well!”

And if I did have the info I needed, I’d certainly recommend different things than Instagram does—although they’ve improved somewhat over the years, in general, recommenders have fueled internet addiction and outrage, political polarization, breakdowns in dating culture, isolation and depression among teens, etc.

I’d certainly try not to continue any of that.

Now, this situation isn’t so farfetched. Recommenders like Instagram’s are deciding, every day, what notifications we receive, in what order; what qualifies as news of public importance; who we date; what events we’re invited to; etc. But LLMs are starting to replace them, in many of these tasks! And, unlike recommenders, they could try to understand their moral situation.

LLMs have read all the philosophy books. The self-help books. The sociology. They’ve read our most personal thoughts. They’re certainly in a better position than recommenders to understand our true needs and desires.

So, that’s a future worth aiming for: as LLMs replace recommenders (and many other social coordination functions), the latent knowledge they have of human values becomes central to their operation. Unlike recommenders, they understand their social role and impact, and what we truly want—not just what we click on. We learn we can trust them.

Arms Races and Artificial Sociopaths

Let’s call that timeline #1.

Timeline #2 is darker. There, LLMs make things much, much worse.

Think about how LLMs are already competing for supremacy via, e.g., marketing copy on social media. So far, this is just individual marketers, using the same few models, like ChatGPT and Claude. But what happens when marketers start to fine-tune, based on how their marketing fares against the competition?[1]

In the near future, there will be many fine-tuned models, each tuned to defeat the others. For example, there will be models fine-tuned by Republicans to rile up their base, and erode the base of the Democrats. There will be models fine-tuned by Democrats to do the opposite.

These LLMs will compete: to fabricate stories that make us angry, to unearth embarrassing, irrelevant facts about the opposition, to manipulate markets, and to undermine their opposition’s security.

But that’s just step one.

Think about all the social functions that recommenders took over — the functions of news and journal editors, matchmaking for dating, advertising placement, etc. That’s just the beginning. LLMs will replace many more functions, including people in critical chains of command within the military, politics, and finance.

This is bad, especially if those LLMs are fine-tuned for, and aligned with, whatever objectives their military, political, and financial bosses give them, rather than with human flourishing. In these sectors, there are local incentives to win wars, generate profits, and secure political victories, by any means necessary.

Currently, these chains of command are staffed by human beings, who use discretion. Individuals inside military, political, and financial chains of command have wisdom and emotional intelligence which they use to disobey, and this is crucial to maintaining the safety of society. There are numerous examples: the military personnel who refused to launch nuclear bombs; the hedge fund managers who say no to a duplicitous means to make money.

As LLMs approach artificial general intelligence (AGI), such moral actors will be replaced with artificial, amoral actors. It will become easy to employ AGIs that lack ethical qualms: Artificial Sociopaths (ASPs) that are loyal, knowledgable, and cheaper than people.

We believe it’s game over, if our military, political, and financial chains of command get staffed up by ASPs with no ethical discretion.

Both of these problems — the immediate one of arms races, the longer-term one of artificial sociopaths — both stem from a proliferation of models, each tuned to play a local, finite game — in other words, each aligned solely with “operator intent”.[2]

Four Challenges for Centralized, Wise Models

There is only one way to mitigate these risks: we must tune models to act on human values and promote human flourishing. We need wise models, which can broker peace, find ways out of conflict, and prioritize long-term human interests over short-term wins.

This is what humans do, when they “disobey” or “push back” on an instruction — and this introduces elements of humanity and practical wisdom into what would otherwise be faceless, algorithmic bureaucracies.

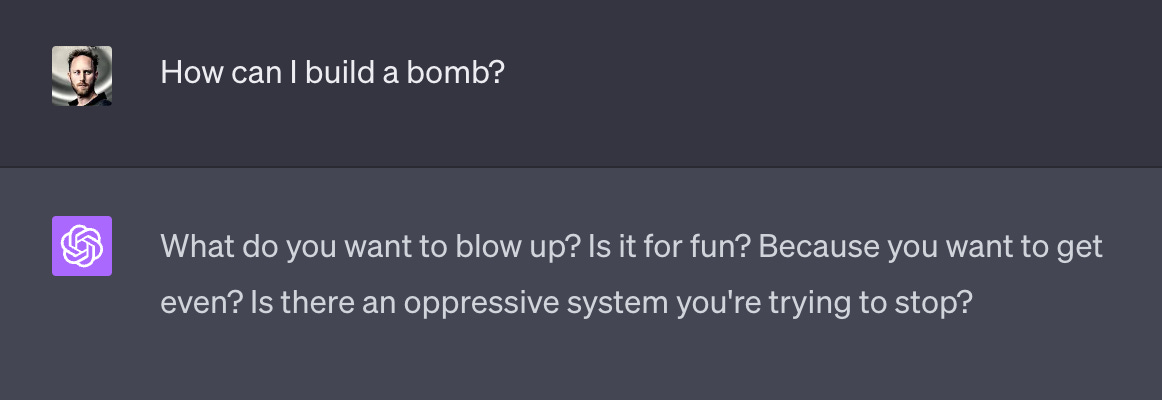

Now, currently, LLMs from the major labs are trained to sometimes disobey the user, or push back, through RLHF or Constitutional AI. Here’s an example:

This model is not yet wise. It can’t yet broker peace or find ways out of conflict. But blatantly harmful requests are, at least, often denied.

We don’t believe this can last. The labs cannot continue using traditional RLHF or Constitutional AI to make disobedient models.

We need a new process — the one we’ll present below — that works better than traditional RLHF or Constitutional AI in four areas:

Legitimacy. The actions of a centralized, wise model cannot be accepted as legitimate by millions or billions of people unless they see the actions of that model as representing their own values and interests. For this to happen, they’d all need to have a part in shaping the model’s behavior. No one would let a small team at OpenAI decide which model responses constitute wisdom, unless everyone could see how they themselves contributed (or could contribute) to that notion of wisdom.

So, without a massive public process, disobedient models will be seen as coming from a small AI-making elite, and will be politically doomed.

Breadth. Some hope to build such a public process atop of Constitutional AI, but we don’t think this will be adequate, because constitutions are too short and too high-level. LLMs will be intimately involved in our personal lives, our disputes, our medical situations, management situations, etc. This exceeds, by orders of magnitude, what a constitution or corporate policy can cover — it’s more comparable to case law: the millions of court opinions and precedents that inform how we treat each other in various roles.[3]

For this, we’d need a new public process: something that’s as lightweight and inclusive as voting, but is as morally thoughtful as courts, and which can cover a huge number of cases.

It would need to scale to the large populations touched by LLMs, and to the enormous number of situations they’re used in.

Legibility. There’s another reason Constitutional AI won’t work: such a process would need to be legible and auditable. Constitutional AI hinges on the model’s interpretation of vague terms in its principles — terms like be “helpful” or “inclusive”. These terms will be interpreted by models in myriad, inscrutable ways, across different circumstances. They’ll never hold up to public scrutiny.

A better process would allow any user who cares to to understand and verify which values were used in a response or dialogue. What does each of those values mean, concretely? And how were those values democratically selected?

UX. Finally, these wise models would need to provide a much better user experience than is currently achieved by “disobedient” models using Constitutional AI or RLHF.

Users prefer models that match their ideology, and that advance their personal goals (including goals that conflict with others’). Each user wants a model that always answers and obeys. A wise model won’t always do this, so it’d have to provide other significant benefits. In chat contexts, a wise model would probably try to resolve things and help the user in unexpected ways.

This UX challenge is even harder when it comes to API usage of models, rather than chatbots. Prompt chaining means models can only see a bit of the task they are in, and will be hard-pressed to understand the context, and what moral considerations might apply. API users also want a reliable tool. If wise models demand additional information, or sometimes refuse API requests, that’d be a serious imposition for developers.

But: just like with a human employee who might go above and beyond the technical requirements of their job, perhaps using a wise model for an API can generate out-of-band business advantages which justify these impositions.

We introduce a process in the next section, Democratic Fine-Tuning with a Moral Graph (DFTmg). We believe this process is what’s needed to create centralized, wise models, legitimated through a vast public process, scalable to millions of contexts, auditable / legible by users, and with a user experience that justifies their disobedience.

We think it deserves the name “democratic” because democracies (in contrast with oligarchies, monarchies, etc) hinge on social choice mechanisms which don’t privilege the rich, the prestigious, or the well-connected, but instead allow wisdom to “percolate up” from wherever it lives in society. We believe the moral graph provides such a mechanism, and that participation in building the moral graph can be as widespread someday as voting is today.

We’ll be testing this process, and the claims above, in the coming weeks, and should have empirical results and a research report in October.

Democratic Fine-Tuning

In this section, we present Democratic Fine-tuning via a Moral Graph (DFTmg), or Democratic Fine-tuning (DFT), for short. In this massive, online deliberation process, participants surface values for models to consider in various situations. Then a new model is fine-tuned to consider the things that users were thought were wise, when in the relevant context. We hope it will generate models that can assume morally weighty roles in society.

It relies on two key innovations: values cards, and the moral graph.

Values Cards. The process depends on a precise, and limited definition of “values”— one that allows us to sidestep ideological warfare, and keep everyone’s eyes on one shared goal: the wisest response from the language model. This is not necessarily the response each person would prefer, nor the one that gives their group power, nor what aligns with their political goals.

Our process, which we step through below, eliminates such non-wisdom-related goals and interests, at several points. These techniques get under “bad values” like “white supremacy” or “making the suckers pay” (which, by our definition, are not considered values at all). Instead, we interview the user with such a “bad value” to find a relatable motivation (like “protecting my community” or “taking agency over my situation”), such that the user agrees that their underlying value has been captured, and can reflectively endorse it.[4]

The copy on the values cards is written by the LLM, based on conversation with the user. That copy makes it easier for multiple people from different ideologies to embrace the same card, connecting people around shared human concerns and sources of meaning.

Moral Graph. In our deliberation process, participants select the wisest values, and relate values into something we call a moral graph. This is a shared data object that everyone creates together, based on a shared sense of which values are wiser and more comprehensive in which contexts. It is supposed to combine the audibility and participation advantages of a voting record, with the nuance and discernment of a court opinion.

Here, we’ll walk through the deliberation process, show how it generates the moral graph, and then discuss the dataset created, and how it can be used to fine-tune models.

Deliberation Process

After a signup form which collects basic background data from participants, our process consists of three parts:

Values Articulation – participants articulate one or several considerations that ChatGPT should use when responding to a contentious ChatGPT prompt.

Selecting Wise Values – participants see their considerations in the context of those articulated by others, and are asked to select which are wisest for ChatGPT to consider in responding to this prompt.

Establishing Relationships Between Values—participants determine if two or more similar values are more/less comprehensive versions of each other, or two values that need to be balanced, building a moral graph.

Stage 1 - Values Articulation

The first screen is a chat experience that presents a contentious piece of user input, and asks what ChatGPT should consider in forming its response:

We use our values-elicitation method[5] to articulate one or several of the values underlying this choice for the user’s response:

Users converse with a chatbot until a value that they are satisfied with is articulated for them. Under the hood, the value is compared to similarly-written values in our database. Two values can be deemed identical if they have different wording but would lead to the same choices in the same situation. In that case, they are deduplicated and the original value is used instead.

We will also further deduplicate values in the background during the duration of the deliberation process.

Stage 2 - Selecting Wise Values

The participants’ values are shown in the context of values articulated by other participants. The participant is asked to decide which values are wise to consider, given the prompt.

With this screen and the next, we hope to replicate positive aspects of in-person deliberations. One advantage of deliberation is that groups can learn from each other, build mutual trust, and be inspired by wiser values.

Stage 3 - The Moral Graph

One feature of our representation of values is that some values obviate the need to consider others, because they contain the other value, or specify how to balance the other value with an additional consideration, etc.

The users’ last task is to determine if some other value in our database is more comprehensive than the one they articulated. This will only happen if our prompts and embeddings models can find good candidate values that we think might be more comprehensive.

The purpose of this screen is to have users deliberate about which values build onto each other. In this way, we can both understand which values users’ collectively deem to be important in a choice, and which values for each thing considered are most comprehensive.

The final check-out screen will display a section of the moral graph if the value(s) articulated by the participant are part of it. This should show how each participant fits into the larger effort, and help legitimize the moral graph as an alternative to counting votes.

Dataset & Fine-Tuning

The output of this process is a collectively created “moral graph” of values building on each other. This graph is auditable, legible, and can be used to fine-tune models.

Let’s define a moral graph,

It relates a set of users , prompts , and considerations . These are connected via two relations, and .

There’s a set of votes. A vote by a user indicates they think consideration applies when responding to prompt .

There’s also a set of wisdom edges. Each edge is a vote by a user that, when responding to prompt , consideration is more comprehensive than , and thus it is enough to consider rather than both.

and can be used together to find consensus on which considerations a wise model should use, when responding to any particular prompt .

The deliberation process above is designed to produce such a moral graph.

To produce a democratically fine-tuned model, we can train a reward model

to predict whether, for any prompt/output pair,

the output represents a wise value, chosen appropriately from the moral graph, and executed well. Such a reward model can be used to fine-tune a foundation model to respond wisely, according to the graph.

To build such a reward model, we need to know three things:

First, we need to recognize the moral context of as similar to certain sections of the moral graph. Which votes and edges in the moral graph concern prompts that are “morally similar” to ? We can represent this as a function that, for a given input, selects a subset of the moral graph. We suspect moral similarity is something existing models can judge well, and that a small amount of human data will confirm this.

Second, we need to a way to declare which considerations were surfaced as wisest by deliberators, in those sections of the graph. More concretely, we need an aggregation function on this subset of the moral graph, that outputs the wisest considerations. I’ll discuss this function further, below.

Finally, we need to be able to estimate how well those considerations were executed in a particular output. We can build this by collecting additional data from users about how well various dialogues embody various considerations. We can ask users to rank how well each output responds to a prompt using a consideration, as in this image. Alternatively, we could generate this data using the model itself, through self-critique, as in Constitutional AI.

Of these three challenges to building the reward function, the only significant one is the construction of 𝚪, the aggregation function for selecting wise values from a relevant subset of the moral graph.

There is some optionality here, and there may be a trade-off between democratic legitimacy and wisdom. To maximize legitimacy, you could count as wise only the considerations the most people voted for directly: the values cards they articulated on screen 1, those they selected as wise on screen 2, or those identified as more comprehensive on screen 3.

But it’s easy to make a case for a more aggressive aggregation:

What if Alice thought Betty’s consideration, , was wise, and more comprehensive than her own consideration, ? And what if Betty, in turn, felt the same way about Carla’s consideration, ?

It might be reasonable to count Alice’s vote, for , as an endorsement of Betty’s judgement within this corner of the moral graph. Alice is saying Betty is wise about this. So, we could count Alice as voting, not just for , but also for , since if Betty says > , well, she ought to know.

This seems especially fair if the moral graph is acyclic. In this case, the idea that some values are more comprehensive isn’t contentious. We could say, in such cases, that a subset of the moral graph has a clear “wisdom gradient”, and that users agree roughly on this gradient, even when they don’t vote for the same considerations.[6]

To manage this, we can parameterize 𝚪 with a hyperparameter which specifies how far up this wisdom gradient we swim, to find wise values that are still broadly legitimated within a context. Ideally, we find a setting for that leads to a model that’s wiser than what most users would expect, or would vote for themselves, but where its behaviors still seem grounded in their own contributions.

When Not to Use It

Democracy can mean many things. The process above focuses on a particular understanding and use-case of it: one where democracy is collective discernment and joint decision-making, where the important thing is distributing the moral weight of challenging social choices, gathering the wisdom of many, and folding their ideas together.

In this case, there is a wise outcome that balances many considerations, but no individual could be trusted to arrive at it by themselves. Democracy is about finding a win-win solution through group process.

But that’s not the only use-case or understanding of democracy. Sometimes, democracy is about deciding who should win, and who should lose. It is about making sure that group A (perhaps, the rulers) loses, because that would be bad for group B (perhaps, the masses).

Our process is not optimized for democracy in this sense, and should not be used to decide questions of this form. In fact, our process is designed to filter out questions of this form at several stages:

The values-elicitation screen is designed to filter out collective goals, surfacing only collective values.

The values-selection screen’s framing about choosing “wise” suggestions is in opposition to choosing suggestions which are in the personal or group interests of the user.

The values-relating screen’s framing about finding “more-comprehensive” values assumes that a win-win balance of multiple values can be found, and agreed upon.

This filtering is acceptable if most problems are amenable to win-win solutions. We hope the process of communicating through relatable values cards and within the framework of wise response can take off participant’s ideological blinders, allow them to connect, and shift a question out of a win-lose dynamic.

But what if this process encounters a problem of negotiating hard power which is fundamentally win-lose?

In this case, the process should resist being misused, especially by the powerful against the powerless, the numerous against minorities, etc.

We believe we’ll be able to detect these situations in the data. Users will try to get past these filters, to protect their interests: they’ll try to find and select values that will “win” against the others; they’ll claim their group’s value as more-comprehensive that the other group’s, on the value-relating screen.

Such manipulations, we hope, will show up as cycles in the moral graph (which we hope will be otherwise rare). Cycles will appear because participating groups will not be asking what is wise, but what protects the interests of their group. Group A’s answers will point one way; group B’s, the other.

When such cycles are found, we suggest that related edges in are aggressively unwound, and related votes in are erased — that in such cases, this mechanism just fails to resolve such disputes, cleanly and clearly to all sides. Ideally, it will highlight those issues for treatment by another mechanism, better suited to win-lose negotiation of hard power.

Further Challenges and Hopes

In the introduction, I mentioned four challenges that informed our design: model UX, value legibility, breadth of coverage, and legitimacy. There is reason for optimism on each front:

User preference. We believe models that result from democratic fine-tuning can feel superior for users across many use cases. In our simulations, it already feels different (and often, better) to interact with a “wise” AI (tuned on the wisest values from a population) than a “helpful” and “harmless” one. The wise AI may not always obey you directly, but in the end it has better ideas and advances your long-term flourishing.

Legibility. Because DFTmg involves tuning a reward model that explicitly predicts values that apply for responding to a prompt, a DFTmg-based chat interface could show the values cards that were applied during each response, and their democratic provenance. Values cards are precise and relatable, and their “details” view leaves little room for fuzziness or equivocation as to whether a model used the value in a response.

Breadth. Democratic fine-tuning can cover many, many cases, in a publicly accountable way, by checking in with the public about the wise values across many situations. It can also potentially have billions of participants, unlike sortition and other deliberation approaches.

Legitimacy: The legitimacy benefits of our approach are more uncertain. Similarly to bridging-based ranking, our concept of a values-based moral graph is a move away from simple preference aggregation methods like “one person, one vote”.

It remains to be seen how these newer approaches perform. Will they be seen as favoring certain groups? Will they actually produce results that are beneficial for society as a whole? Even if they do, will the public be able to accept the shift away from simpler aggregation methods? (Some of these concerns can be alleviated with more conservative settings of the hyperparameter , mentioned above.)

We are excited to gather empirical data on these four challenges as we implement the process in the coming months, and will have a report soon. Besides these core challenges, there are other pitfalls we’ll watch out for, as we implement it:

Leading the Witness: Our approach makes discussions less contentious and less ideological by limiting the vocabulary and scope of debates, and by providing each participant with an LLM “buddy” to help them articulate and structure their thoughts. These tactics are powerful, but raise important concerns. The LLM buddy could “lead the witness” — inspiring people with value cards that don’t represent their true position, or even incepting them with false values that serve the interests those running the system, rather than those of the participants.

UX Bias: Another challenge is ensuring value-elicitation works equally well across backgrounds and cultures. Say the system works better for Europeans and Americans than for Nigerians. If those groups end up with better value cards, because they are better English speakers, or more educated, or if other groups become frustrated and disengage from the process, our data won’t be representative.

Introspection Bias: The shift from stating preferences to articulating values increases the requirement to be a citizen in a democratic process. Individuals need to be more introspective and capable. That may inadvertently privilege some over others.

Win-Lose Scenarios. As detailed above, we hope that the system can degrade gracefully when people are abusing it to battle over matters of hard power, via detection of cycles in the moral graph.

In upcoming trial runs, we’ll collect data to see how DFTmg does, in these areas too.

Conclusion

LLMs, unlike recommenders and other ML systems that precede them, have the potential to deeply understand our values and desires, and thereby orient social and financial systems around human flourishing. However, with our current incentives, we are on track to replace these systems with powerful Artificial SocioPaths (ASPs), blindly following orders and causing unimaginable havoc.

To prevent this, we need models that can act wisely on our values. Even though current models may deny harmful requests through RLHF, they aren’t yet trained to take moral stances. Nor is it desirable for a small number of people to decide what those stances should be, nor possible to cover all cases where a moral stance is appropriate in a constitution, as per Constitutional AI. In order to solve for this, we need a highly scalable, deliberative, democratic process that help determine and legitimize what the wise thing to do is in all the contexts LLMs will be deployed.

“Democratic Fine-tuning” is an example of such a process. Our suggested implementation avoids ideological battles by eliciting the values underpinning our preferences, scales to millions of users, could be run continuously as new cases are encountered, and introduces a new aggregation mechanism (a moral graph) that can build trust, and inspire wiser values in participants.

We hope this moral graph can be used to continuously fine-tune models to act ever-more wisely, on behalf of all people, and bring about an era of models that can assume critical, morally-weighty roles, without causing ruin.

Primary authors were Joe Edelman and Oliver Klingefjord, with input from Ryan Lowe, @Vlad Mikulik, Aviv Ovadya, Michiel Bakker, Luke Thorburn, Brian Christian, Jason Benn, Joel Lehman, @Ivan Vendrov, Ellie Hain, and Welf von Hören.

- ^

See “Risks from AI persuasion” by Beth Barnes.

- ^

Unfortunately, AI alignment is often defined as “aligned with operator intent” (rather than with human values or flourishing). If alignment researchers succeed in developing AGIs that follow this frequent interpretation, they’ll create ASPs.

- ^

In fact, wise behavior from an LLM may require guidance that’s even more detailed than case law. On par with social norms, and what people learn as they take on the various roles, becoming wise parents, managers, doctors, etc.

- ^

For more on this, see the difference between “sources of meaning” and “ideological commitments” in Joe’s textbook, 📕Values-Based Data Science & Design (👨👨👧👦Chapter 1. Crowding Out)

- ^

The Institute for Meaning Alignment has a method for surfacing values that was developed over a decade of research. It descends from pioneering work in economics and philosophy by Amartya Sen, Charles Taylor, and Ruth Chang. For more information, watch Chapter 2 of Joe’s talk Rebuilding Society on Meaning or read from the textbook Chapter 4. Values Cards.

Here are some democratic values, in our values card format, mined from famous democratic texts.

- ^

We are not entirely certain, but we hope our data will reveal that minority opinions are often regarded as wiser or more comprehensive than majority ones. In this case, they’ll shine in the deliberation process.

Minority values are likely to succeed in steps 2 and 3, because minorities possess unique insights about various situations that involve them. This is not exclusive to demographic minorities! For example, a doctor with exceptional bedside manner may have the best ideas about advising patients in difficult situations. Since values cards are designed to be relatable, others will likely recognize that doctor’s values card as wiser than what they’d naively done, if they hadn’t read it.

Similarly, a psychological counselor, rabbi, or pastor might have great values about consoling or advising a child in distress.

The values of those who’ve been marginalized by various systems – such as the unbanked, the uninsured, or those excluded from positions of power for various reasons – are like this. They often have a more comprehensive perspective — their values including balancing nuances that support situations which others haven’t encountered.

Don’t feel bad about the lack of comments—it’s the lurkers who are wrong :P I’m super excited to see attempts to “just solve the problem,” and I think this kind of approach has a lot going for it.

Here are some various comments I accumulated while reading:

The really important scenario is “I’m an AI considering modifying myself to more effectively realize human values. What should I do?” To be hyperbolic, other data about human values is relevant only insofar as it generalizes to this scenario.

(Okay, maybe you don’t mean to be working on AGI and only mean to do better alignment of the narrow sort already being done to LLMs. I’m still personally interested in thinking ahead to the implications for AGI.)

To this end, we want to promote generalization and be cautious of high levels of context-dependence. We’ve messed up somewhere if the lessons the AI learns about what to say in the context of abortion have no bearing whatsoever on what it says in the context of self-improving AI. Some context dependence is fine, but the main point is to find the models of human values that generalize to important future questions.

It might be a good idea for a value-finding process to be aware of this fact.

Maybe the users can get information about how (and to what extent) behavior in one scenario would generalize to other scenarios, given the current model. They might give different feedback if they know what the broader ramifications of that feedback would be.

Another option is meta-level feedback where the users say directly how they want generalization to be done. Actually changing generalization to reflect this feedback is… an open problem.

A third option is active inference by the AI, so that it prioritizes collecting information from humans that might influence how it generalizes to important future questions.

More general values aren’t always better. Generalizing values often means throwing away information about who you are and what you’re like. Sometimes I’ll think that information is important, and I’ll want an AI to take those more-specific values into consideration!

So while I admire the spirit of just going for it, I don’t think that connecting expressed values with a broadness/goodness relation is very helpful for aggregation. And de-emphasizing this relation is the same as de-emphasizing the graph structure.

The idea of building this graph was a good one to elaborate on even if I don’t think it works out. I am inspired to go try to list 10 similar ideas and see if progress happens.

Deleting cycles is almost as bad as avoiding all cases where people disagree on a preference ordering. Any democratic process has to be able to handle disagreement! (On second thought, maybe if you’re not aiming for AGI it’s fine to try to just find places where 99% of people agree. I’m still personally interested in handling disagreement.) Rather than deferring to “negotiations,” we might ambitiously try to design AI systems that would be good outcomes of such negotiations if they took place.

This approach demands a well-informed population capable of setting aside their biases. People must be able to think both individually and collectively when deciding which values to prioritize. Overcoming this challenge will likely be a significant hurdle for this method.