Beware unfinished bridges

This guy don’t wanna battle, he’s shook

’Cause ain’t no such things as halfway crooks- 8 Mile

There is a commonly cited typology of cyclists where cyclists are divided into four groups:

Strong & Fearless (will ride in car lanes)

Enthused & Confident (will ride in unprotected bike lanes)

Interested but Concerned (will ride in protected bike lanes)

No Way No How (will only ride in paths away from cars)

I came across this typology because I’ve been learning about urban design recently, and it’s got me thinking. There’s all sorts of push amongst urban designers for adding more and more bike lanes. But is doing so a good idea?

Maybe. There are a lot factors to consider. But I think that a very important thing to keep in mind are thresholds.

It will take me some time to explain what I mean by that. Let me begin with a concrete example.

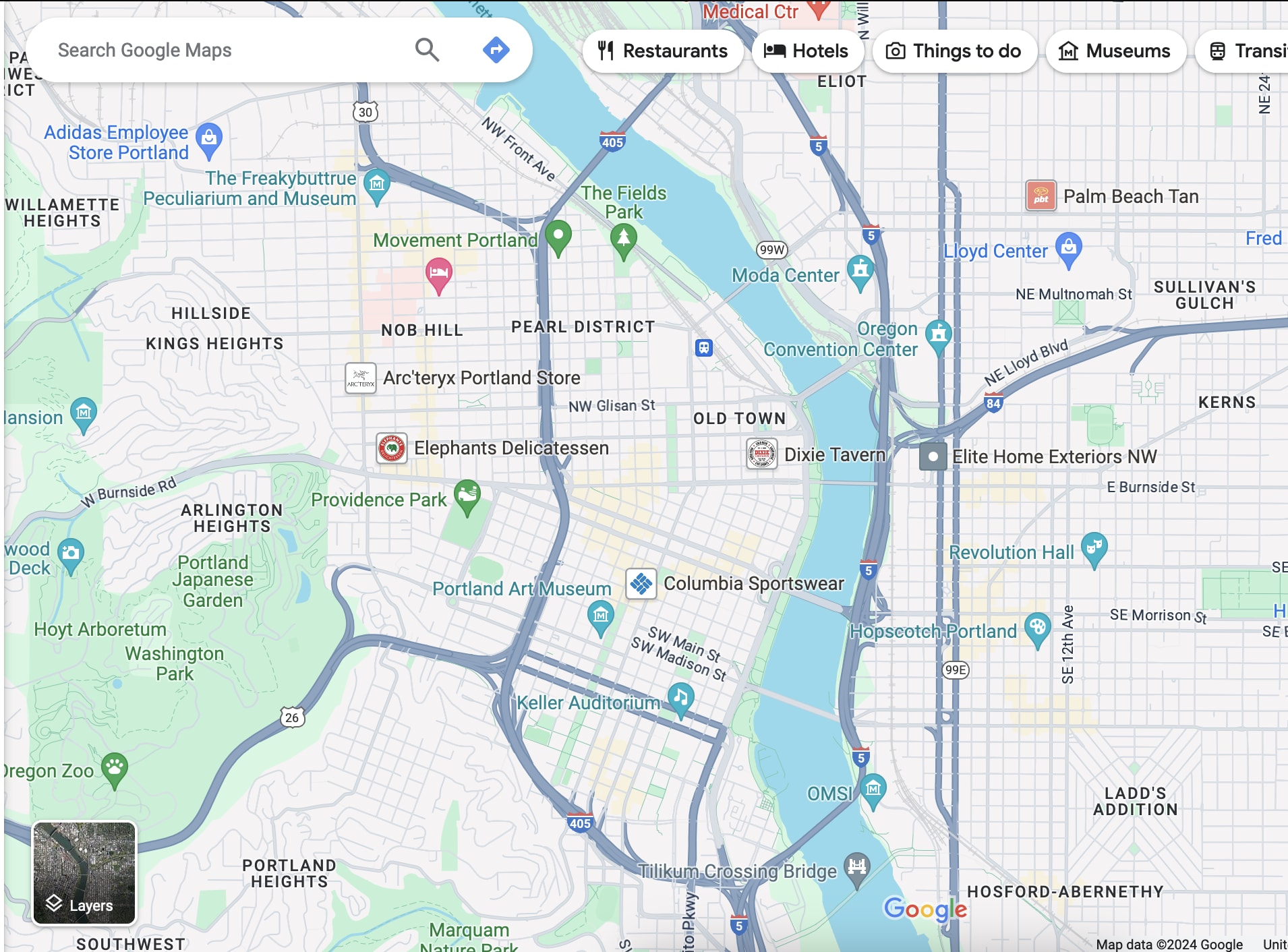

I live in northwest Portland. There is a beautiful, protected bike lane alongside Naito Parkway that is pretty close to my apartment.

It basically runs along the west side of the Willamette River.

Which is pretty awesome. I think of it as a “bike highway”.

But I have a problem: like the majority of people, I fall into the “Interested but Concerned” group and am only comfortable riding my bike in protected bike lanes. However, there aren’t any protected bike lanes that will get me from my apartment to Naito Parkway. And there often aren’t any protected bike lanes that will get me from Naito Parkway to my end destination.

In practice I am somewhat flexible and will find ways to get to and from Naito Parkway (sidewalk, riding in the street, streetcar, bus), but for the sake of argument, let’s just assume that there is no flexibility. Let’s assume that as a type III “Interested but Concerned” bicyclist I have zero willingness to be flexible. During a bike trip, I will not mix modes of transportation, and I will never ride my bike in a car lane or in an unprotected bike lane. With this assumption, the beautiful bike lane alongside Naito Parkway provides me with zero value.[1]

Why zero? Isn’t that a bit extreme? Shouldn’t we avoid black and white thinking? Surely it provides some value, right? No, no, and no.

In our hypothetical situation where I am inflexible, the Naito Parkway bike lane provides me with zero value.

I don’t have a way of biking from my apartment to Naito Parkway.

I don’t have a way of biking from Naito Parkway to most of my destinations.

If I don’t have a way to get to or from Naito Parkway, I will never actually use it. And if I’m never actually using it, it’s never providing me with any value.

Let’s take this even further. Suppose I start off at point A, Naito Parkway is point E, and my destination is point G. Suppose you built a protected bike lane that got me from point A to point B. In that scenario, the beautiful bike lane alongside Naito Parkway would still provide me with zero value.

Why? I still have no way of accessing it. I can now get from point A to point B, but I still can’t get from point B to point C, point C to point D, D to E, E to F, or F to G. I only receive value once I have a way of moving between each of the six sets of points:

A to B

B to C

C to D

D to E

E to F

F to G

There is a threshold.

If I can move between zero pairs of those points I receive zero value.

If I can move between one pair of those points I receive zero value.

If I can move between two pairs of those points I receive zero value.

If I can move between three pairs of those points I receive zero value.

If I can move between four pairs of those points I receive zero value.

If I can move between five pairs of those points I receive zero value.

If I can move between six pairs of those points I receive positive value.

I only receive positive value once that threshold is met.

Why does this matter? Well, say that you are the city of Portland and you are deciding whether to add an unprotected bike lane between points A and B. You have to ask yourself in what way you expect this new unprotected bike lane to add value for people.

If you just add that one bike lane and then stop, I don’t see the new bike lane getting many people past a threshold that would yield positive value for them. I think it’d function largely as an unfinished bridge.[2]

However, if the new bike lane is one step in a larger plan to build a complete bridge, so to speak, then that starts seeming to me like something that might be a good idea. The “larger plan” part is crucial though: you only get value once the bridge is complete, so if you’re going to start building a bridge, you better make sure you have plans to finish it.

America’s response to covid seems like one example of this.

If I’m remembering correctly from Zvi’s blog posts, he criticized the US’s policy for being a sort of worst of both worlds middle ground. A strong, decisive requirement to enforce things like masking and distancing might have actually eradicated the virus and thus been worthwhile. But if you’re not going to take an aggressive enough stance, you should just forget it: half-hearted mitigation policies don’t do enough to “complete the bridge” and so aren’t worth the economic and social costs.

It’s not a perfect example. The “unfinished bridge” here provides positive value, not zero value. But I think the amount of positive value is low enough that it would be useful to round it down to zero. The important thing is that you get a big jump in value once you cross some threshold of progress.

I think a lot of philanthropic causes are probably in a similar boat.

When there are lots of small groups spread around making very marginal progress on a bunch of different goals, it’s as if they’re building a bunch of unfinished bridges. This too isn’t a perfect example because the “unfinished bridges” provide some value, but like the covid example, I think the amount of value is small enough that we can just round it to zero.

On the other hand, when people get a little barbaric and rally around a single cause, there might be enough concentration of force to complete the bridge.

Perhaps more generally: The effectiveness of energy put into an action can easily be a non-linear function. Most gain in value may be achieved at a certain energy level, such that energy differences significantly below or above that level hardly change anything.

In some cases the function may even be non-monotonic, where spending some larger amount of energy is actually worse than spending some smaller amount.

This combines well with Robin Hanson’s theory that signaling explains most public choice oddities. Showing that we care about bike riders doesn’t require that we actually make the city work for bike riders.

Well, this is really just networking effects. Also why it’s really hard to break out with your new hot dating app or social media website, no matter how much Tinder or Twitter suck. For your app to provide utility to users, it needs… users. Good luck breaking that stalemate.

Roads, or bike lanes, are a very literal network. Usefulness suddenly undergone a phase transition only when you hit the percolation point.

Sort of a tangent, but when I ride I technically fall into the “strong & fearless” group, but don’t feel like it.

I’d much prefer protected bike infrastructure, but for a variety of reasons it’s often unavailable. In those cases, at least in an urban setting, I generally prefer to ride in the lane with cars over using an unprotected bike lane. To me this is obvious:

in the lane the cars will definitely see you

if you ride far enough into the lane cars can’t pass you by “squeezing by”, getting dangerously close

less likely to put yourself in precarious situations at intersections

Unprotected bike lanes seem like the worse possible option, and find it strange that anyone falls into the “enthused & confident” category.

Hm yeah, I feel the same way. Good point.

Bike lanes don’t only exist to get people from point A to point B. They also exist to provide an outlet for biking as a recreational activity.

I would trust decisions based on empiric measurements of usage of the bike lanes a lot over your analysis when it comes to justifying decisions by cities.

So, sure, there is a threshold effect in whether you get value from bike lanes on your complex journey from point A to point G. But other people throughout the city have different threshold effects:

Other people are starting and ending their trips from other points; some people are even starting and ending their trip entirely on Naito Parkway.

People have a variety of different tolerances for how much they are willing to bike in streets, as you mention.

Even people who don’t like biking in streets often have some flexibility. You say that you personally are flexible, “but for the sake of argument, let’s just assume that there is no flexibility”. But in real life, even many people who absolutely refuse to bike in traffic might be happy to walk their bike on the sidewalk (or whatever) for a single block, in order to connect two long stretches of beautiful bike path.

When you add together a million different possible journeys across thousands of different people, each with their own threshold effects, the sum of the utility provided by each new bike lane probably ends up looking much more like a smooth continuum of incremental benefits per each new bike lane that is added to a city’s network, with no killer threshold effects. This is very different from a bridge, where indeed half a bridge is not useful to any portion of the city’s residents.

Therefore, I don’t think “if you’re going to start building [a bike lane network], you better m ake sure you have plans to finish it”. Rather, I think adding random pieces of the network piecemeal (as random roads undergo construction work for other reasons, perhaps) is a totally reasonable thing for cities to do.

Another example of individual threshold effects adding up to continuous benefit from the provider’s perspective: suppose I only like listening to thrash-metal songs on Spotify. Whenever Spotify adds a song from a genre I don’t care for—pop, classical, doom-metal, whatever—it provides literally ZERO value to me! There’s a huge threshold effect, where I only care when spotify adds thrash-metal songs! But of course, since everyone has different preferences, the overall effect of adding songs from Spotify’s perspective is to provide an incremental benefit to the quality of their product each time they add a song. (Disclaimer: I am not actually a thrash-metal fanatic.)

Well I understand that you are talking about how people in the interested but concerned group are affected by the “unfinished bridge”, we should note that there are still 13% of people who would use an unprotected bike lane.

Further, the unfinished bridge helps build up to addressing the network problem, with less investment than a protected bike lane, we can move from 7% of cyclists using the system to 13%.

Finally, this is a chicken and egg sort of problem. People need to cycle to make the bike lanes worth it, but no one will start cycling without any bike lanes. If society deems more cyclists to be a social good, we need finished bridges, but unfinished bridges are still better than no bridges.