A Scalable Urban Design and the Single Building City

Crossposted from Medium. Initial description of proposed infrastructure.

Epistemic status: I’ve read a few books on the subject, spent a few months trying different things and working out the details, and am fairly confident this is at least worth a shot; definitely some kinks to work out; would appreciate writing and technical feedback.

-updated 07/26/2020 with more notes on sunlight, windows, and fires-

-transit network section updated 08/02/2020-

This article will be an exploration of some of the main issues people encounter with cities, the causes of those issues, and a comprehensive set of partial solutions and possible infrastructural innovations.

Problems with Existing Cities

One of the main issues people have with cities is the cost of housing. If you try to buy a house in a suburban or urban area, the suburban house will tend to be cheaper. In fact, if you just try to buy land, the suburban land will be cheaper. The land can be most of the property price difference for small buildings, though there may be other things at play like an artificially limited housing supply.

Why is space so expensive in a city? Well, it’s extremely valuable. Everyone wants to live there. Utilities such as water, electricity, trash, internet, and mail are much cheaper. There are more people around. You can buy whatever you want from tons of different stores. There’s a certain economy of scale about it. A lot of people and things in one place reduce a lot of the cost of moving around or bridging distances. There are more job opportunities. Everyone wants to put businesses there. It’s a lot easier to find people to work for you with more people nearby looking for a job.

Actually, why are buildings taller in a city? Higher is more expensive, right? Construction costs tend to depend most on whether the frame is wood, concrete, or steel, and whether there are stairs or elevators. Both of these mean higher numbered floors are more expensive. Despite this, if the land is valuable enough, it’s easier to make a 2nd or 20th floor than it is to buy more land and put a single story building up. In other words, buildings tend to be taller because the space they afford is worth the added expense.

Urban design, infrastructure, and regulations can also be uncoordinated, raising prices or imposing perverse restrictions. There are many different people with different aims: Max doesn’t want to live near a factory. Rachel likes driving fast. A borough, city, county, state, and country might each have a bunch of rules that try to satisfy conflicting interests, but sometimes those rules are really out of date, or the people that made (or keep, or enforce) the rules aren’t exactly looking out for everybody. New technologies that revolutionize different aspects of life are implemented haphazardly or fought over. People speculate on land and veto infrastructure.

The US, for example, is home to many building regulations and codes: Factory-built homes are required to have permanently attached chassis, have worse financing options and much stricter energy and fire codes, and are sometimes only permitted on certain monthly fee sites. The ADA requires an elevator for new buildings over 3 stories tall. Many counties in the US have lot size, parking, and apartment size minimums; height and square footage restrictions; and copious single use zoning. The entire US is regulated by the International Code Council, which has things like 220ft² minimum apartment sizes.

Some places in the US let residents veto new development, and the residents take full advantage of this to raise their own property values. Land is valued for the kind of legal hoops it can jump through. There are huge farms just outside some cities that can’t be redeveloped into the housing that so many want. These restrictions can be fairly helpful in some cases, but the overall effect massively increases the cost of housing.

A workable rule of thumb in the US is that $1 in monthly rent can typically support $100 in Total Project Costs and yield a reasonable return of 10–12% on the cash you put in a building. If demand (rent) for space is higher and construction is unconstrained by space or regulations, construction will grow to satisfy the demand and bring rents down again. Transportation, height limits, permits, and other regulations can raise the cost of construction (or limit the supply at various construction price points). A $200/mo 150ft² room (or 200ft² total space including shared space) of a 4-floor walkup in a dense city isn’t out of the question financially. It is, however, illegal.

It doesn’t help that cities around the world prioritize cars in transport. Streets have grown wider and have free parking lanes. Gas isn’t taxed enough to factor in the harm to the environment. Half the land in many city centers is just road and parking. Have you ever had a hard time walking down a street because there were too many people walking? Doesn’t happen a lot, right? But that’s true for cars every day.

Transit throughput is a measure of people moved at some speed over time divided by the total width of space dedicated to the given travel mode. For example, a 4 foot sidewalk supports 2 people per second walking at 3 mph past a point. A foot of space can support 1.5 people-mph per second walking, 2 driving on streets, 3.5 highway driving, 4 cycling, 10 by highway moped, 50 by local rail, and 80 by commuter rail. Transit throughput is a good illustration of space usage for various long trip options. Higher throughput transit is made more useful in cities, where space is at a premium.

In the US people own cars, and cars have an average total cost of ownership of ~$10k per year. Cars heavily impact pedestrian safety, leading to a different civic environment. Some cities are so car oriented you can’t even walk to that many places from your home. Asphalt roads cost $20/ft² to build, have ongoing maintenance costs and a resurfacing event, and only last about 30 years before needing to be completely repaved. This translates to a ~$1/ft² annual total cost of a road network. There are many cities in the US where the total tax base of most neighborhoods doesn’t cover this cost.

On the other hand, mass transit is so space efficient that it’s often cost effective to just bore a tunnel for it to use, despite this costing 5x as much as laying rail at-grade (at surface level), including stations. Cars are subsidized with free roads and parking and they’re still ~3x the total cost per passenger-mile of rail. Rail is unfortunately surprisingly expensive in the US vs other countries, as well as burdened by its own host of regulations and planning failures. Bus and train frequencies, despite being cheap to increase (or even just maintain off-hours), are too weak in many places to draw riders and empower the places they connect.

Cities around the world enjoy a wide range of densities. Here’s a density map of Paris:

The actual city boundaries aren’t so clear: The land around the city becomes valuable enough to develop as the city itself grows. Importantly, you can’t design for one density; density changes over time, and even a particular section will have spiking density around things like train stops.

In lower density areas, it can be pretty annoying to get around: Walkability is a measure of how friendly an area is to walking, and there are plenty of places that just don’t measure up. For example the LA metropolitan area, home to 13 million people at a population density of 2,700/mi²: Everyone owns a car, there’s 765 ft² of road per person, almost every public street is a stroad, and more land is set aside for parking than for housing. Higher density areas have more things reachable easily with your own two feet, and on top of that areas without cars or with tree shade are just nicer to view and walk around in.

Possible Solutions

OK, so cities and suburbs around the world have a bunch of issues impacting quality of life. What can we do about that?

A lot of regulations stifle the usable space market in perverse ways, leading to far higher prices. Others give undue priority and subsidy to cars. There’s not much you can do without letting many of these regulations go. It’d be nice to make an informed legal overhaul in a particular municipality, but existing systems aren’t usually amenable to such drastic change. There are still incremental gains to be had by working to reform regulations over time and implementing a few of the things to be presented here, but there’s another approach:

Just make a new city.

It actually happens fairly often already! It doesn’t always go that well, but people get into this sort of thing with a lot of different ideas and they aren’t always in line with what’s possible, both economically and socially. Still, Paul Romer, the Charter Cities Institute, Pronomos, and Apollo Projects outline some of the possible (mostly institutional) advantages and are hoping more of this kind of thing will happen soon.

We’ll focus on the infrastructure side of things in this article, looking at possible solutions to our whirlwind of issues plaguing cities. One initial strategy that works well here is to look at how different countries have solved some of these issues (fewer regulations, AVAC, limited car access, congestion tax, rail), but in this article we’ll also be looking at more theoretical solutions.

The best place to put a new city is usually right outside an old one, as close as you can get while still being cheap enough to buy all the land you need. You get to take advantage of a bunch of existing demand and services. Suburbs have the right idea, but the wrong vision. I’d like to make a note here that many of the following things will have to be modified, or in fact may not work altogether, for some places like very poor countries or extreme climates.

Land Ownership

First up is a Land Value Tax, which is a way to incentivize building higher and to disincentivize empty lots or land speculation. Tax the land based on regular appraisals of value either per plot or on a zone basis. There’s often an issue where appraisals only happen at sales and market value diverges wildly from this, leading to wildly under-appraised land or property. The current major source of municipal income in the US is a combination of property tax and sales tax. A land value tax is a nice alternative because it consolidates taxes onto something more straightforward which doesn’t decrease as a result of being taxed.

An alternative is a Harberger Tax, which works roughly like this: The owner of a plot states a price that they are willing to sell the plot and everything on it for (likely including a buffer for ownership frictional overhead). They’re then taxed a fraction of this price regularly. Anyone can buy the plot for the stated price at any time. Now market forces set appraisals and the feedback is faster, another fix to diverging market values. It disincentivizes density more, while being easier to maintain and far more accurate than formal appraisals.

One of these taxes being implemented should lead to noticeably faster and more even intensification, or increasing investment, in valuable areas.

Transportation Infrastructure

Next up is cars. Large vehicles are necessary for some things: Specifically, construction and large deliveries. Trash can be handled with an automated vacuum collection (AVAC) system cheaper than with trucks. We’ll address mail and packages later. Let’s go with single lane one way streets as the base network and let the market handle parking. Vehicles slow significantly in thin lanes with no shoulders and near pedestrians, contributing to safety. You might need to further limit speed somehow for very small vehicles.

Now we just need a congestion tax, implemented with automatic tolls around the city perimeter that charge either based on how long the vehicle is in the city or total street usage. Tune prices for low congestion, but high overall usage.

The main form of long-trip transportation here will be low speed highways at first. Each highway can be replaced with mass transit when there’s enough demand. Straighter roads affording higher speeds are more expensive, so with higher per-capita income highways can be higher speed and replaced with mass transit earlier.

(boundaries not to scale) Increasing street layout intensity: Purple dots are stations / highway access, dashed lines are transit, solid lines are streets; Left shows initial infrastructure spread and one-way direction arrows; Middle shows initial intensification; Right shows full saturation of streets.

An approximate street grid (following natural terrain limitations and probably looking nothing like above) maximizes walkability and service area by stations or highway entrances while minimizing street space and expense. If we add in streets just along the mass transit lines, we get another 20% reduction in average trip length to the train stop (due to the 10 min serviceable area becoming an octagon) with the tradeoff of less homogenous street traffic. (I’m sorry Jane Jacobs, for I have sinned) You can have the streets zig zag just enough to erase the endless street visual effect for 1% more street.

As train technology was introduced, rail has been implemented in major cities to great effect, but in a bit of a haphazard way: New lines are planned every so often and in large bursts over years, and construction of these lines is made more expensive by high land prices, crossing existing transport networks, and lack of coordination in switching transit modes.

In order to make scaling transport infrastructure cheaper, future transportation requirements should be mapped out in detail. Land for this future infrastructure can be instead leased for a period of time, or sold with clauses for construction standards permitting unimpeded future development. For example, a lot where a certain volume necessary for rail isn’t built through and can be reacquired by the city cheaply. This can still accommodate intensive development long before land is necessary and cheaper uses in years leading up to construction. Construction planning ahead of time can also massively reduce cost to private construction atop streets, roads, and rail.

Here we’ll examine the case of transportation where the development in question is a suburb of an existing city. Long trips will be mostly be either commuting or local transportation. Demand will likely be significant to and from the parent city center as well as homogenous locally.

A grid-like network with one axis aligned with commuting will work well for this scenario. The transit network can extend past the initial new city land boundaries to near the overall metro area center (or until existing mass transit lines). At the lowest level of demand, highways within the development handle long trips locally and existing metro-area wide infrastructure handles commuting. When demand is high enough, buses and later rail connections to the parent city center can replace the highways.

It may be helpful to make a deal with the parent city to collectively purchase the land for a future rail connection early and share the cost of constructing it. This connection benefits the parent city as well, allowing stops along the line to enrich intermediate land.

If new city population and land ever contests the parent, or if this development is not a suburb at all but a standalone development, transit lines can be planned radially to better scale with demand.

Mopeds are significantly lighter than cars, and building streets or highways for them (especially anything elevated) should be cheaper as a result. It may be necessary to prioritize them in a road network for safety. Without a switch to mass transit at low enough densities, a tax is also eventually necessary to limit the pollution caused by that many more engines.

For those who have only ever seen infrequent or weekday-only mass transit, be aware that it’s not particularly difficult or expensive to have high frequency trains or both local and commuter service at most stops. Maybe you wouldn’t consider taking the train if it came every hour, but what if it came every 3 minutes? With enough ridership, that frequency isn’t just feasible but actually quite manageable. Local service may only average 35 mph, but commuter service that makes fewer stops (one every 4 miles or more) may average 60+ mph even in dense areas.

A common complaint with mass transit is negative externalities caused by others like with music, calls, busking, groping, and the homeless. Some cities have successfully implemented fines for things like playing music or busking, and the homeless are only on mass transit in a few places that have particularly failed in reasonable treatment. Other things like groping are cultural and hard to catch.

There’s actually another approach to transit that eliminates walking to or waiting for trains altogether, or any kind of figuring out the (already quite simple) service network. It doesn’t make any stops, can be extremely fast, and achieves similar throughput to mass transit. In fact, it’s a kind of transit pretty similar to a fully autonomous car system if the cars were a lot smaller and had no headway. Personal Rapid Transit (PRT) unfortunately also is relatively young and hasn’t been realized at scale anywhere yet, and for that reason we’ll continue with mass transit in this article.

Raised Streets

Earlier we covered street land waste. Manhattan isn’t particularly bad, but 36% of the land is still streets. Those streets are the veins of the city, letting people move between buildings and delivering shipments to businesses.

But Manhattan is 23 mi² and the land is worth an estimated $1.7 trillion, so an average of $3k/ft². That’s a lot of valuable space; Why not just raise the street? Maybe it’s more expensive to raise car lanes due to vehicle weight (try putting a semi on an asphalt shingle roof), but it’s not hard to raise everything but those lanes. Roofs you can walk on are quite common and only a bit more expensive over time. If we’re raising the streets, why not parks as well? A green roof is just a sturdier roof with a drainage system and a bunch of dirt and plants, still only around $40/ft².

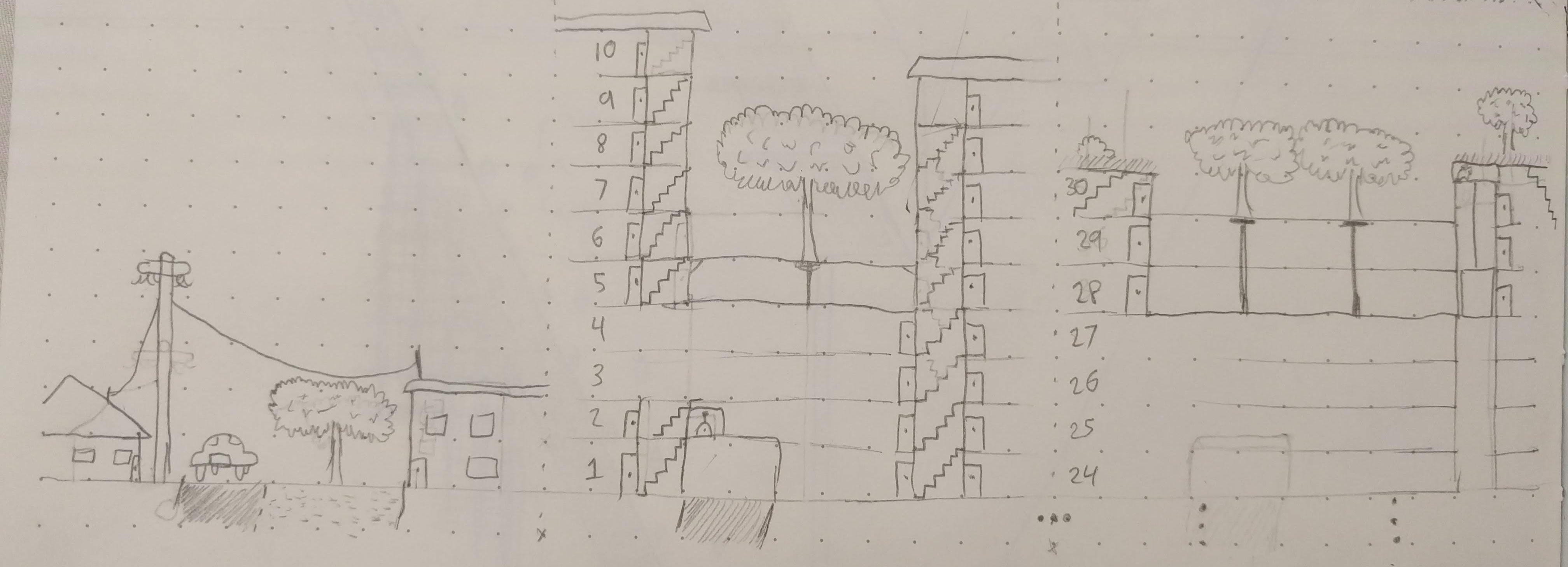

Several street heights and transitions with faint skyline outline; Numbers indicate height of street in floor #.

So raise the pedestrian street and sell the constructed space to lot owners on either side if the floor heights line up. If it’s wide enough, you can sell the space separately. This is where having standards or incentives for floor heights can help a lot for a greenfield development: Ensuring floors in buildings exist at the street level allows shops and spaces to line the street. Equal neighboring rooftop heights allow continuous parks (just step from the edge of one building to the next). Not only that, but because buildings on opposite sides of the street are now touching, you can do things like allow shared stairs or elevators that service both buildings, lowering costs further.

Several street cross sections; Numbers indicate floor #.

What about construction? Trucks and cranes need space to actually build and tear down buildings, right? OK, give them that space. They don’t need the whole street. A given dedicated shaft for cranes can service anywhere the crane can reach, requiring much less space relative to the service area.

What about sunlight and windows? People want a certain amount of contact with the outside. Keep in mind here that people are different and that some aren’t nearly as concerned with sunlight or windows in their own home. There are also those that desire window contact but not sunlight, and perhaps vice versa. Imposing one view of peoples’ needs is premature here, and extremely expensive. Let the people that are willing to make the tradeoff make it. Full-spectrum LEDs can emulate sunlight in sufficient intensity with minimal space requirements.

For others, you can bring columns of outside enclosed with windows and textured facades down into buildings periodically. Or for more space and sunlight or a more interesting view, you can limit some buildings to dense thin rows lining the streets or even just towers with lower construction filling in the gaps (or use some kind of per-floor area ratio limiting density but allowing a variety of shapes). This is an area worth further exploration. Assessments on the value of spaces with or without windows, sunlight, or nice views can allow charging negative externalities to existing property caused by new development to the new owners, allowing the market to regulate more of this.

What about fires and fire engines? Here we must be very humble: Even glass and metal skyscrapers can go up in flames. Fires are a force of nature to be dealt with with the utmost caution. All buildings will need to be fitted with fire sprinklers at the minimum. Firemen will thankfully be close enough not to require fire engines or emergency lanes, but it’s possible many more firemen will be needed in extreme emergencies. This would be an area of research with large potential wins. More metrics and more confidence is needed in the strategies available to fight fires in dense city sections. A few possible techniques to start with are CO2 emergency networks, brick or solid stone firebreak building sections, and more extensive fire drills. This is a critical thing to address, but I believe it is possible.

Package Delivery

Let’s tie up a thread from earlier: Package delivery. Today we use small trucks to deliver packages in many places. Last mile delivery is about half the cost of shipments in the US, doesn’t happen on Sundays, and adds a day latency for in and out-going packages. There’s a startup called Starship with a bunch of $5k robots that use machine learning and a bunch of logic to navigate sidewalks and mostly deliver food for $2 a delivery.

Hey, that’s actually not a bad idea. Let’s just let the bots share the one-way lanes at first and give them a separated lane under raised streets. That way they can go faster to start with, a lot faster in the separated lanes, and don’t need nearly as much logic, machine learning, sensors, or wheels to navigate. Or instead of using shared lanes we can lay 3 ft diameter tubes underground just like the AVAC trash system to allow high speeds before raised streets. We can even have one big lane and one small one or otherwise mix smaller robots in for smaller packages. Actually, this is pretty much exactly how PRT works, just with packages instead of people. You could even upgrade the network later to let people ride if it’s reliable enough. Robots deliver to lock boxes or directly to an owned space. Delivery fees should be… under a cent for smaller packages?! Hold on…

But that’s exactly it: An autonomous toy car can deliver your food for less than a cent, and in a minute or two along separated lanes. It can also deliver similarly beer, medication, toilet paper, and just about anything small you might get from Walmart. Or Amazon. A larger 2 foot wide bot could do it for a few cents. It’s just a box with a motor, battery, computer chip, camera, and wheels.

The effects this would have on retail and food are enormous. Convenience stores and cheaper restaurants have the option of moving to much cheaper locations and just serving all their products remotely. There’d be no need for waiters or customer-friendly warehouse aisles. These stores would serve a far wider area, competing for customers that can choose from any of them. More stores would pop up serving niche items previously impossible to justify economically. If the food arrives in a few minutes, it’s still fresh and you can just send dishes back with another bot. There’d still be space for higher end restaurants, and a new market for space to sit and eat decoupled from cheaper eateries.

An Arcology

We talked about density earlier. Manhattan has an average of 72k ppl/mi². Paris: 56k, Tokyo: 16k, Barcelona: 42k, New York City: 27k (remember how city boundaries aren’t well defined?).

There’s also the amount of built space (including roads and parks) per person in a city. This is distinct from inverse density: Imagine a single occupant 2-story house. The built space is twice (briefly ignoring usable space ratios) the land the occupant is using. In NYC the average built space is 1010 ft²/person (but Manhattan is likely lower), Manilla: 250, Paris & Tokyo: 500, LA: 3660. (note differing Paris and Tokyo densities)

Keep in mind that it is usable space per person in a given setting and not land population density that determines how crowded it feels, as well as the fact that density and crowding are primarily a function of demand and the market as a whole. Private interests self regulate crowding: Cities only get as crowded as Paris if people and businesses want to be there. Overcrowding is partly psychological: Cultures have varying ideas of personal space in different contexts. The design here just allows the density of land use (and says nothing of crowding) and infrastructural capacity to increase beyond what is currently achievable.

We also mentioned raised streets earlier. Let’s examine a valuable district where all the streets are raised and incentives on rooftop height coordination have led to an even set of rooftops with a considerable amount of street inset 1–3 floors from the collective rooftops.

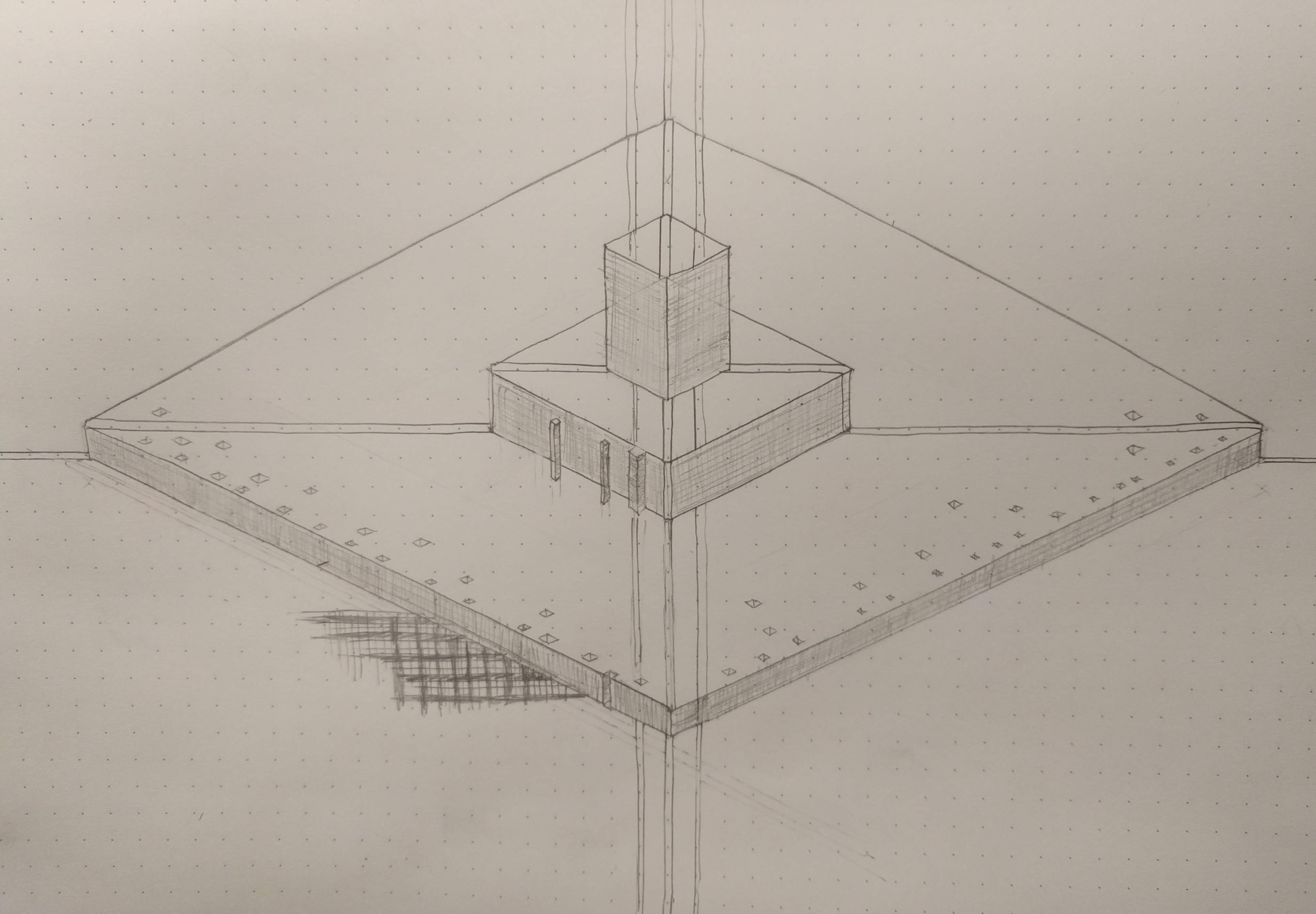

(area near a train stop) This is what peak efficiency looks like: Streets not filled in and spiky high-rise demand gradient not shown. The outer space is also buildings. (it’s buildings all the way down)

Imagine a world with a massive single building center near a train stop, a sort of groundscraper. However, the “single building” is secretly many adjacent buildings masquerading as one. The roof has plenty of parks and trees and there are inset streets leading everywhere, with elevators you can take down into the building strewn throughout the rooftop. You can sort-of think of the whole place reversed, as a massive underground building extending into the ground from the vantage of a set of streets and parks. The building has many skylights and roof fans bringing light and air into it, and at the sides of the building are elevators leading to the streets below.

Density and the buildings themselves may be by no means this uniform, but consider this: A place like this with a height of 35 floors (the height of Sidewalk Labs’ PMX, the modular plyscraper), 500 ft² built space per person, and 1.4 gross : usable square feet would give 1.4 million ppl/mi², or 20 times the average density of Manhattan. Even a height of 5 floors, a traditional limit for wood construction and requiring no elevators, would give 200k ppl/mi², which is denser than most parts of Manhattan. A height of 12 floors with streets outside around floor 6 might have an average of 10 floors of usable space and still not require elevators.

A single street level actually isn’t enough to handle some of these densities, even with the affordance for higher street to floor ratios granted by raising the streets. You’d need multiple floors similar to what malls have, but with more mixed use development and integrated into the street network. Periodic half-floor offsets can promote varying paths and aid exploration among citizens, driving street sociability and discoverability. You don’t need that many street levels, either: 1 street level near the roof per 10 floors total height should be sufficient.

And indeed, the densities involved here easily dwarf existing cities without much expense. You could get anywhere in no time; There’d be so many things reachable you’d never have to go far at all. Every shop would have hundreds of thousands of potential customers regardless of location. Every school, library, and park would as well. The economic opportunity is unreal in cities with this level of demand, but you have to build the infrastructure for it, and you need the demand first.

Demand for Raised Streets

How much demand? At some point the average land value assessment along a particular section of street reaches a threshold where the city figures it will be profitable to raise the section. The financial model I’m imagining here is: The city sells the section to a large developer that then works with and sells space to adjacent building owners and other parties.

All that’s required to raise a section of street is to construct a long building with a walkable roof.

For example, if street about to be raised is 30 ft wide, such a planned building would then have a usable width at its base of 20 ft (to accommodate the truck lane) and higher floor widths of 30 ft. Since the new building space can be sold, the actual cost of raising the pedestrian street is just the difference between the cost of placing it on a roof vs on the ground. The only cost of accommodating the truck lane is the section of support columns spanning the vertical gap.

This shows the demand threshold for raising a street is just about when the land is valuable enough for private investors to build mostly multi-story buildings along the unraised street.

That demand doesn’t come so easily: If everyone wanted to live in a new town, suburbs would fill instantly with starry-eyed folks. Reality is much more gradual and uncertain. Economic incentives may greatly aid this process, but nothing happens overnight and infrastructure must accommodate the world as it is, not as how it wishes it could be.

Lower Densities

However, even starting with large residential plots and cheap land, the aforementioned infrastructure performs admirably: At first, while density is extremely low, cars are perfectly suitable albeit a little expensive due to asphalt maintenance. As density increases, people can sell their cars and begin biking to transit. Let’s assume a constraint on mass transit stops where people want to be able to let their kids walk to a primary school near the stop. That gives a population floor of about 4000 people per stop. People can bike to transit above a density of 900 ppl/mi² if there are streets along rail lines increasing reachable area. For walking, this gives a figure of 9000 ppl/mi². Because the infrastructure is incremental, the city can add rail lines, expand train stations and streets, and even add more streets and parks as demand appears.

This infrastructure is also legitimately cheaper and better than typical car-oriented suburbs at being, well, a suburb. People use suburbs to refer to a wide range of densities, from 100–2200 ppl/mi² with a median of 1800–2000, with the variation mostly from residential lot sizes. The rail system isn’t very helpful below 900 ppl/mi² (without electric scooters), so we’ll only compare denser suburbs. With the proposed changes the streets are safer, the utilities (mostly trash & mail) cheaper, the financial incentives more aligned, the retail even more convenient, and there is a ready path of intensification to a full city. Any of these changes helps in isolation to the rest. For example, while raised streets enable hyperdensity, nothing else proposed here depends on them.

Conclusion

Let’s take all these things together: In a world where you can get cheap housing in or quite close to a massive hub of culture. A world where all shipments and returns are cheaper and faster, where you can order food from anywhere quickly for no cost, where you can travel anywhere in the city with exceptional speed. A world where all the streets have shade and no cars, there’s considerably less pollution, and the view is amazing even in the densest sections.

That’s a world I’d like to see.

Hm, frankly I have quite a few issues with this proposal, mostly boiling down to it ignoring the real world problems. Sorry if it sounds harsh, know that I didn’t mean it. Frankly, I like the idea of arcology very much myself, but I don’t believe it can work with the existing technologies only, at least not in an economically viable way.

>Keep in mind here that people are different and that some aren’t nearly as concerned with sunlight or windows in their own home.

Willingness of people to tolerate lack of sunlight (just like lack of any other nice thing) tends to have strong negative correlation with they ability to pay premium for it. So in practice we’re talking about poor people being confined to [effectively] underground ghettos and only richer people being able to afford natural sunlight in their homes. At least this fact should be explicitly mentioned and addressed in the discussion.

> you can bring columns of outside enclosed with windows and textured facades down into buildings periodically

Such things do exist, and they serve exactly one purpose—making the building nominally compliant with the regulations, while not increasing actual liveablility at all, especially in higher latitudes, where the sun will pretty much never be seen at the bottom of such a shaft. Speaking here from the experience of living a few years in Saint Petersburg, Russia, which is famous for courtyards of this type.

>A world where all the streets have shade and no cars

You do understand this sounds attractive only for a certain type of climates, and for others “every street being mostly in shadow” is a big downside, right?

A few more questions:

- It’s not just sunlight “underground” levels are deprived of. It’s also any kind of personal space outside one’s residence (like yard, terrace or patio), and yes any kind of view from a window, other than a wall of another building.

- What happens if you need to rebuild something on the −3d floor underneath a walking street?

- Do you have any calculations regarding the crane space? I know nothing about construction machinery, but just from gawking at it, seems like a crane can’t reach much further than a width of an average building. Which would imply that they kind of do require more or less entire street to be able to reach at every point of every building on it.

- Firemen aren’t the only ones who need to get around quickly, it also includes police and ambulance. And the latter also needs transport to carry patients and equipment.

- Speaking of firemen, carrying personnel isn’t the only function of a fire engine. Granted, you have CO2 and high-pressure water delivered through dedicated networks of pipes (which need to be built and maintained). What about hoses, chemical extinguishers, breathing apparatuses, tools, ladders and whatever other equipment is used in modern fire fighting—are firemen expected to carry it all on their backs? Also, how they would get with a fire hose on say 5th floor above a pedestrian-only street which is physically incapable of supporting a fire engine?

- How healthy is it from the noise/exhaust perspective to have a fully enclosed tunnel filled with trucks right behind your wall or underneath your floor? How much insulation and ventilation is required to make it healthy for the residents, as well as for the drivers and bus riders, and how much more expensive it makes the project?

- Regular cities in rainy climates see their drainage systems overflown from time to time. It usually ends up in small floods, blocked roads, damage to vehicles and first floors of the buildings. What such an event would look like with a park or street atop of a very wide building?

- What about snow? It won’t just flow down the drain pipe. Usually people clean it from the rooftops (which are often made inclined to facilitate the process) more or less manually and then use heavy machinery to clean it off the streets. You explicitly state that the top level is too weak to allow heavy machinery on it, so cleaning it can be a very labor-intensive task. Same goes to many other park-maintenance work, come to think about it.

- One of the common problems of modern cities is that they stink. Making them denser and more enclosed increases this problem proportionally.

- On a single lane street with no parking lane, every accident or failure immobilizing a car will completely block the traffic.

- Starship delivers relatively cheap stuff—like food—over regular streets where there’s plenty of bystanders. If you suggest delivering everything, including things like laptopts and phones and jewelry, by small robots driving through enclosed ways directly through your city’s ghetto, theft will become quite an issue.

- Without PRT, which is optional in your model as far as I understand it, disabled, old, obese, sick, injured or just very physically unfit people will have no good way of getting around.

- A roof of most high-raise building is covered by various air conditioning equipment, ventilation exhausts and such. There’ll be only more of these in buildings which have no streets between them. So a rooftop park should be full of these things, puffing out stench and hot air. You may raise them above the walking level, but it still won’t look very good.

- This creates a whole lot of new infrastructure every new building needs to be plugged into, as well as new requirements (ability to support extra weight, noise insulation), which makes new development a lot more expensive.

Overall it seems like you’re referring to “Seeing Like a State” as an example of what not to do, than go and do exactly what it warns against (full disclosure—I’m actually familiar with the book only from the SSC post). Rotating an evenly-spaced rectangular grid 45° and adding evenly spaced rectangular zig-zag to it doesn’t stop it from being an evenly-spaced rectangular grid. Obviously modern cities aren’t utilizing the space perfectly, but I believe in large part that “wasted” space provides slack to accommodate imperfect coordination, things breaking, environment and terrain, and other fuzziness of the real world. Your proposal addresses only a part of the coordination problems, by assuming the place is uniquely well-governed.

First, I want to thank you for thinking critically about this. I appreciate your efforts and line of reasoning.

So first, note that this is correlation and not a direct relationship. I’d love to see a study here.

I think this also is mostly resolved by the market: Poor people wanting sunlight will live more crowded in sunlit sections. Middle class people not needing sunlight will live further down in less crowded conditions. Rich people will just pay the premium and live in spacious conditions with sun.

If sunlight turns out to be a huge constraint, it reduces maximum density considerably but still allows for densities multiple times the densest cities we see today.

I next mention dense thin rows of buildings lining streets. The streets would be north/south to handle this.

Yeah, the streets with shade thing is just an example to show walkability in nice climates. I agree you can’t do all of these in such climates, and that may make them poor choices to starting such a city there.

You can have thinner walking streets supported by the buildings to the side as well as the roof of the building supporting it, but in general you may have to shut down that street when rebuilding it.

Typically 230 ft, so ideally you have a grid of crane points spaced so half the diagonal is that distance. With a square grid that gives 320 ft between adjacent grid points. You can either space streets to line up with this grid or the grid will be more constrained somehow.

Police, fire, and medical can still use truck lanes to carry a bunch of stuff quickly in an emergency. 15 mph is faster when things are much closer together. Elevators can bring them with equipment to the street level, where so long as their equipment is relatively lightweight, it can still be electrically powered and easy to move.

You can use the building across the street, ladders on the outside of that building, extendable emergency bridges, something like a really tall maneuverable ladder that attaches to rails on another building, or a helicopter with a platform dangling from it.

Heavy trucks are about 80 db at 50 ft going 30 mph. I think soundproofing a 60 db reduction isn’t that expensive, maybe $2 / sq ft of wall in the US? Since the air pollution is concentrated in one area, you can use air filters to get rid of most of it. Ventilation is also a lot cheaper than full HVAC.

Yeah, you either need very good drainage reliability and throughput or this won’t work in certain climates.

I’m not too sure about this; maybe salt the streets or use airplanes to blanket everything in salt? Maybe heat smaller sections and have people push snow into those sections? Also, you can still have some space on streets or roofs for heavy machinery in exchange for higher construction costs for that part of the roof.

So, crowding is the same. I don’t think either of us knows the exact causes of city stink, which would be helpful here. Air filters and ventilation should help address this.

This depends a bit on how close you need parking to be in the case of failure. There’s still some parking, and even a parking lane can be filled with cars, as is usually the case in Manhattan. I imagine the solution here is adding paid parking spots until this is not a huge issue or having low latency towing.

If robots are in a fully enclosed tube, it’s still pretty hard to just take one. The robots can also communicate position and video live with a computer system and the city can respond quickly if something is off.

This already isn’t an issue with trains. Lightweight electric wheelchairs shouldn’t be an issue on the street. A few ramps at changing street levels can accommodate forced street level transitions.

Air filters and lower surface area help a lot with stink and cooling here. Piping ventilation from buildings under streets through side buildings should help with concentrating this into parks. From there, concentrating HVAC units on rooftops minimizes interaction with walking space. You can also do most of the heating/cooling with ground-based heat pumps to reduce these units entirely to huge fans.

Definitely more expensive; However, I don’t think it’s that much more: Noise insulation is pretty cheap. The extra weight supported here is the same eventual overall weight. Again, this expense is borne when it becomes worth it anyway.

*Note: I’ve also only read Scott’s post.

This is important and I want to address this further. Note that the design here doesn’t say “here’s exactly how the buildings are laid out and what they’re used for”, nor “we’re designing for this fixed density”. Furthermore, the design is not a whole lot different in scope from what we see today in many suburbs and cities. Grids are pretty common, and Jane Jacobs (sort of the antithesis of Le Corbusier, the father of Brasilia’s design) basically thinks they’re great (and a lot better than suburb culdesacs). A grid is fine in optimal conditions, and if the terrain and environment make that a dumb idea just drop the grid and design around the terrain. It’s not critical to have a perfect grid or anything.

While your other summaries are fair, this is very much not what I said. I’m not saying poor people want sunlight more, I’m saying humans regardless of income on average prefer having sunlight and whatever else windows give. (Proof: building codes, seasonal affective disorder, human evolutionary history and any housing market ever. Take e.g. the Bay Area rental housing—rooms with tiny windows do exist but they are confined to the cheapest segment of the market, which is exactly my point. While huge floor-to-ceiling panoramic windows is a common feature of luxury housing everywhere.)

So while yes some middle-class people will be ok with living on the underground levels, and some poor people will chip in to live more crowded but with sunlight. But large and by the principle will be (as it is now to some extent) - the higher floor the higher price. Compare how now, large and buy people live in old rundown apartments when they can’t afford any better, although sure there’s some fraction of people who can and just don’t care. So basically what I’m saying, is that your city’s worst neighborhoods are now very literally hidden under nice parks and walking streets with upscale restaurants (as you said cheaper restaurants will likely opt for delivery-only), physically invisible for the rich people in their penthouses. And sunlight and fresh air (as in actually fresh, not from HVAC) are in a sense turned from something everyone can have to luxury good. I’d be the last person to discard any project just because it looks ugly, but you need a big fat argument right on top about why it only looks ugly and in fact will be better for everyone (or realistically for most). And just saying “but some people don’t even like sunlight” solves the problem about as well as saying “but some people like to sleep under the open sky” solves the problem of homelessness.

Indeed you mention dense thin rows of buildings, but doesn’t it change the whole calculus here? And more or less turns this into a Manhattan with underground car tunnels, or something close to it? I’m also not quite convinced this approach will work that well even in California, in the sense of making people happy with their view. Plus, when there’s a lot of another problem arises with these shafts—they heat up very quickly without wind. Yes, ventilation, but that costs money and I don’t think I’ve ever seen such a “ventilated courtyard”, so probably nontrivial amount of money.

Why are we talking about 50ft here? I thought, without any sidewalks and extra lanes, on the track-only street it’ll be more like 5 feet from the wall at most. And I’d guess pick noise is acceleration, not steady movement. Likely still can make it work, as well as ventilation, but if the costs were trivial we’d be building under or right next (as in, 10 feet) to highways all the time. Plus, add enclosed space—reflected sound just goes to the opposite wall.

Just. No. The correct procedure is you first remove bulk of the snow, then add salt so any residuals melt and flow down the drains. If you salt half a feet of snow you’ll end up with half a feet of squishy, greyish-brown, caustic mud, which is exactly as good for shoes, clothes, health and city’s appearance as it sounds. Been there, tried that. (Not with airplanes though, this would have added benefit of salting anyone who had imprudence to be out or open their window at that time.)

The problem with melting is that water has huge heat of fusion. Going with your 0.5 miles example, to melt 6 inches of fresh snow—a large but not extraordinary amount to fall in a day or two—you’d need around 1.1 millions kwh of energy, which is on the same order of magnitude 200k people are consuming in winter in one day. That not counting heating it up to the melting point. So again, nothing impossible but even more expenses into infrastructure and electricity or fuel. On the other hand, in colder climates you’ll have to build heavier anyway to protect from cold, so probably making the top layer able to support some kind of machinery is less of an issue.

Yeah, I also thought of a fully enclosed tube, but then you can’t share roads with heavy vehicles and need to build even more infrastructure. Not just the tube, but access ports to it in case a robot breaks and blocks it, something for robots to navigate off, and so on. Skilled people can hack a bike lock in seconds, I don’t think breaking into a robot with a crowbar would take much longer. Not unsolvable problems both, but add more expenses.

Overall yes, you’re totally right that all these problems are solvable by throwing enough money on them (except for no windows in the “underground” levels. You either don’t have them and it’s a problem, or you do and it’s basically a regular densely built city plus some futuristic delivery infrastructure, if I understand the concept correctly). And in most cases it’s not huge amount of money. But those not huge amounts do add up, so does the space that some of the solutions require, and decreases in denizens’ comfort that some of them cause. Combined, it can easily change the outcome of the calculation.

Firstly, I used grids only as a metaphor, obviously there’s nothing wrong with them per se, sorry if that wasn’t obvious.

Yes you do add some flexibility in some points. But the core approach remains the same—top down planning, centered around maximizing a relatively small amount of metrics under an unrealistically small amount of constraints, with a bunch of quick fixes added afterwards. I’m not familiar with how they go around planning successful suburbs and cities from scratch, but I’d guess there’s much more of “Here’s the best practices and approaches that worked in the past, and here’s some good examples, let’s build something similar but fixing the known problems”, and much less of “Here’s the two metrics that matter, lets crank them up as high as possible and then correct for whatever problems might come to mind”.

I think it’s illustrative how your suggested solutions to most of the problems require at least one of the three: governmental spending (air filters, snow, first responders), regulations (noise insulation, walls strength, ventilation) or centralization (robo delivery pipes, centralized heat pumps). The first two are inevitable provided by the government, which is rarely good at fine tuning to the precise needs of the population, the last can be in theory done by a private company, but that would be a monopoly with infinitely high entry barrier for competitors, so no better in practice. So it’s very easy to see how all of the problems—noise, stale air, ugly looking parks, lack of sunlight in winter and sizzling heat in the courtyards in summer—get solved just to the point where almost nobody actually dies and (optimistically) not too many people leave the city, but nowhere nearly enough to make the life there actually pleasant.

Another illustrative point is how when it comes to preferences people might actually have, you reason from the outside view of what’s technically possible. But they can supplement sunlight with LED lights, right? But someone able to walk 50 meters to their car but not 500 meters to the train station can use a wheelchair?Sure they can, but more often than not it’ll make them miserable, and probably incur extra financial costs on the people already not in the best position to handle them.

Thanks again for your input!

OK, I might not understand what you’re saying here. I agree that this is the primary issue people raise and that means this isn’t discussed enough, but I figured that would dominate the article if I focused on it.

A few things… Circulating air even from all the way outside is a lot cheaper and easier to deal with than the sunlight issue, so fresh air is really not a huge issue.

You mention “worst neighborhoods” near the ground implying there is a section of the city where crime is high, but there are no streets near the bottom: Any poor people living below are living in a small space accessible by stairs or elevators directly from the streets at the top.

Idk if this is complete, but here’s a capitalist argument: People vote with their feet. They can always live further out and commute in. If the conditions are actually worse than another place, poorer folks will try it out and leave to enjoy life somewhere more reasonable. If the full negative sunlight/window economic externalities caused by putting up a new building are assessed and charged to the new owner (I should include this), the owner won’t build if he (and others) can’t get enough return on the lower sections. If people don’t like not having sunlight and they’re still there, maybe it’s legitimately worth it to them? For example, maybe they’re earning way more money than they would otherwise.

I think dense thin rows of buildings can still achieve very high per-floor area ratios, maybe 2⁄3 or so, allowing most of the ridiculously high density Manhattan doesn’t come close to. View can probably be included in the negative externalities charged to new construction. Hot air rises, giving a free ventilation force. Just want to note here that moving this amount of air with fans really isn’t that expensive anyway.

Yeah, 50 ft is just the figure I found. Trucks would also likely be going slower than 30 mph. “For every doubling of distance, the sound level reduces by 6 decibels.” Soundproofing is a combination of reflection and absorption; Add absorption materials to reduce echos. People live next to streets with trucks using them already, right?

Fair enough, how about pushing snow into chutes or tubs and having trucks ship it out? Or throw it into the trash AVAC system?

Tbh fast response times, dash cams, high use streets, and police should be enough to handle this even with mixed traffic, although the separated infrastructure pays for itself readily in robot speed and throughput. Navigation can be done either with paint and optical sensors, magnetic markers, or fixed digital broadcasts from frequent points.

OK, the point I’m trying to make here is that these critiques apply as much to existing suburbs and cities as they do here in the sense that: Centralized systems like mass transit, utilities, and emergency services are everywhere. Regulations and codes around building and transportation are everywhere. Government spending on centralized systems and many more things is also everywhere. The amount of top down planning used in existing municipalities is already quite high, and I think this about matches it, not being notably more other than just actually addressing super-high density development. I just don’t think the comparison to master-planning is actually reasonable.

If anything this design moves more things from a flat “no, everything has to be this way” to a “sure if it’s actually worth it” approach to regulation. I’m sure there are things about peoples’ preferences I’m not aware of here, and it’s important to make things a little flexible and open to later change because of that. However, I’m not sure you have a better understanding, either. Existing systems have made the decision for us on a lot of matters and may realistically not have a lot of reason to those decisions.

There’s an existing thing that requires no innovation that makes suburbs much more liveable which is a horseshoe shaped development with the outer loop being park, the middle loop being residential multistory apartment buildings or condos, and the inner loop being commercial. Everyone’s residence building has park on one side and stores on the other.

This also elides several elephants in the room: nobody with power wants cheap housing because poor people create more externalities (crime, noise, destruction of commons, both at home and at the relevant school district). Discrimination along dimensions other than financial have become illegal, so all remaining optimization pressure gets stacked on it. Another is that density seems great to young people and suburbs seem really appealing to families who want more space.

Just want to first note that most of the proposed things require no innovation either.

Multistory buildings (also regulated away in most suburbs) adds ~25% to construction costs. Jane Jacobs also mentions parks being much better if they’re on the way to things, and the ratio of park even today doesn’t approach the scale portrayed. Also want to note that suburbs only exist in a few countries.

Poor countries with cities still exist, and many seem to be getting along well enough (at least getting richer over time). If it’s not that I guess my intuition goes the other way. I imagine police stepping up militance to combat some of these things can work. If discrimination is legitimately a good solution to some urban issues, I’d at least be surprised, but it should still work with the other things here.

The housing market should generally address this. There’s will certainly eventually be parts of the city topped out in density, but until then if space becomes valuable the market will eat that value by making more space. Families can always live in less dense (but still city-density) sections a little further out.

If you’re interested in futuristic concept cities & optimal scaling, check out that part of Robin Hanson’s Age of Em.

I spent most of the lockdown in a small town by a lake and loved it. The future I’d like to see is a future where good jobs are less tied to cities, due to remote work tech like this.

I enjoyed the post. Very excited about cheap delivery infrastructure and vacuum garbage disposal! =3 Actually furious that it hasn’t been made already!

I wonder if it would be possible to design an interior psuedoexterior space with very bright lighting and spacious open ceilings that would pretty much feel like being outdoors. It wouldn’t have to pretend to be an outdoor space and paint the ceiling blue or anything like that, I’ve always found that creepy, but if you raise ceilings and light and ventilate well, maybe that would be enough? Residents would have to supplement their Vitamin D, as it’s very unlikely that they’d be able to maintain the habit of visiting the surface gardens often enough, if the space worked properly. But most people probably need to supplement their Vitamin D regardless (especially during these trying times, by the way).

My main objection is that private ownership of urban land is totally incompatible with approaching an unboundedly low cost of living, as elaborated here https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/fnzZCq4XCeoWGPEp8/a-scalable-urban-design-and-the-single-building-city?commentId=RsctKt8Hpvyr4uZRS but most of your post is still useful even given that.

I have some thoughts about how to ensure that people end up being next to people they want to be next to… I think you do need a mechanism to arrange this. If you get rid of rent as a fitness-selector, haha, some people are going to want to replace that with something. But even without regards to that, a mechanism for this would be really useful for finding places you want, overcoming coordination problems of forming intentional communities, generally planning rearrangements of the city to maximize eudaimonia generation efficiency.

I guess I’ll outline it. This is the Propinquity Cities concept:

Residents (who have funded, maybe up-front, a portion of the construction costs of the city, and pay rates) submit a sort of utility function over features of their dwelling and the types of people and services they want to be near to.

There will need to be some process for keeping accurate records about the features dwellings have. There should be an accurate, up to date list of all of the apartments that face east, have wooden floors, contain a red room etc. Ideally, this would be resident-driven. No one should be unable to find a home that meets any of their weird preferences as a result of some beurocrat not thinking that feature was worth keeping records on.

Hm the residents’ preference functions could also be used to measure the population’s desires and inform ongoing construction. Since all construction is managed by the city, that will be necessary.

The city has an aggregation function over those, which is essentially its occupancy law.

An open process run by the city awards a prize to the group who can produce the highest-scoring allocation of residents to allotments according to the city aggregation function over the resident’s preference functions. The function also tries to avoid moving people around more often than is necessary. Most years (at least once the city has settled into things a bit), a person wont be moved.

Absolute pandemonium on moving day.

New intentional communities form in every corner of the city. Everyone is in a place where they want to be and are wanted. There is no rent to pay.

I attempted to address rent stuff in a reply to your other comment. I generally agree on psuedoexterior spaces.

I expect if intentional communities or micro placement coordination are valuable enough and rent/space unregulated, communities will outbid people with weaker ties both in construction and allocation. It’s possible you can overcome the frictional costs of all this allocation being centrally planned, but I’m skeptical of the overall value.

The taller a building is, the costlier it is to put up another floor. You can build a 10th floor because of land prices but when it comes to the 100th floor the reasons are more often about reasons of signaling.

The OP’s statement “it’s easier to make a 2nd or 100th floor than it is to buy more land and put a single story building up” is technically true. But there is nowhere on Earth where 100-floor buildings are built for anything but prestige. For example, here is a photo of New York City, one of the most expensive bits of land in the world. The World Trade Center is 104 stories tall. None of the other buildings in its immediate vicinity come close to its height. (Though a handful of buildings in New York do compare to the World Trade Center.)

Tokyo, once the most valuable real estate in the entire world, does not have a building with more than 60 floors.

This presents a problem for the tenses used in the quote. It is confusing to use the word “is” to describe a situation that does not exist, as if it did. It would be better to replace “100th” with “20th” or “if the land is valuable enough, it’s easier” with “if the land was valuable enough, it would be easier”.

There are reason why there are no 100-floor buildings build in Tokyo. It’s too expensive. I don’t have the exact numbers but the floor in a single story building in Tokyo might be cheaper.

When thinking about city planning it’s important to distinguish building a 10 floor building because that’s cost effectively from building gigant phalus symbols to demostrate that your building is the biggest.

Thanks, updated.

Regarding artificial sunlight: a technology that imitates it shockingly well in many ways, giving a sense of a window to a light source with infinite distance: https://www.coelux.com/en/about-us/index

You could have a hierarchical system, with many slow lines for local travel, and fewer faster lines for long distance travel. There could be separate systems for small and large packages.a barcode, and perhaps wheels. The lanes are just a moving chain with tracks and fittings. (The boxes would be one of several standard sizes, perhaps each standard size could be twice as big as the last, so you can pack several small boxes together to make a large one) The boxes could be packed end to end, and get a smooth high speed transportation. You would have straight lines in various directions, as well as smoothly curved lines for changing direction.

At junctions you would have a set of points that scanned the barcode and sent each package in the right direction. You would have sections of track designed to accelerate and decelerate packages. These would be parallel to a main line, everything on a main line is moving at the same speed.

You could have a hirarchical system, with many slow lines for local travel, and fewer faster lines for long distance travel. There could be separate systems for small and large packages.

Some of the boxes would have seats in them. You could just get in and fall asleep and end up at your destination.

Advantages of this system:

Strongly maximises throughput per cross sectional area, as on the main throoughways, the boxes can be packed next to each other, and travel fast. (By making the outer walls smooth, air can be encouraged to move with the cargo, minimising air resistance)

No need for batteries. Motors don’t move themselves. All you are transporting is the cargo.

Minimises control circuitry. Only one control system needed per intersection. Completely automatic.

Compatible with regenerative breaking.

This approach is much more conveyor belt.

With this system, instead of cupboards, you would have doors to a small box port. You open a small door in your kitchen, like a kitchen cupboard. The item you want is not in there. You press a button nearby. In a few seconds, a box of stuff is moved from storage beneath your house and to the door. You open the door again, and find what you are looking for. You could call up the same cupboard full of stuff at your friends house, either with a password or identifying object.

It occurred to me recently that this could also be used to mitigate the risk of respiratory pathogens. What if in-person, indoor gatherings were subject to congestion pricing? People could get refunded if they’re vaccinated.

Nice post. I’m excited—is there a place where people who want to work on this sort of thing / live there can coordinate?

Well, the Charter Cities Institute is trying to help make stuff along these lines happen, but they’re probably not as interested in super-high density things. I’ve heard Singapore tends to have better urban planning than other countries. Many European countries and Japan have nice train systems, but still have a lot of cars as well.

I may end up being unable to align with the Charter Cities Institute due to their stance on eminent domain. I hope the reasons are clear from the post, if not, I’ll try to explain it fully. I guess I could do a little post about that. It seems to me that private ownership of land inevitably puts a limit on the affordability/value/qol of cities.

Traditional land ownership puts us in a situation where you must either constantly bleed money just to occupy space, or where you must pay price for land that takes into account its potential use as a device for constantly bleeding money from its occupants. Land is not elastic, so the prices aren’t incentivising anything useful, except for producing density, but we can and probably should and maybe (to get ideal density) have to use other mechanisms to producing density. We can choose a legal system where those costs don’t have to be paid by anyone. If we can buy enough rural land before prices go up, we might not even need the support of the state in order to implement that.

Okay no, I think that’s a full explanation? I don’t think I’ve ever said it that coherently before.

I think the issue I have with this is: Density is expensive and may not be necessary. Let the market decide if it’s a good idea. Deferring the density question to another system begs the question of how efficiently it matches the market and how it works. The city can still tax away land value increases and give that money back in other ways, or limit the total tax. A new city doesn’t exist in a vacuum. It competes in a broader space market and overall market of tax burden. Pricing these too low may just limit city growth.

The price on usable space being close to the value is an effective means of prioritizing who lives where as well as initial motivation to build. That value can lower if the supply increases, or homogenize with good transportation. Land value lowers some from land value increases being taken by the city. A Harberger tax may also cap property prices.

Land prices generally can’t rise significantly until multi-story wood construction saturates buildable land. Depending on whether cross-laminated timber is about as cheap as traditional wood construction and built space per capita, that should happen at a threshold of either around 200k or 1.4m ppl per sq mi. Even if land prices rise significantly, that price is amortized over the number of floors afforded.