When “yang” goes wrong

(Cross-posted from my website. Podcast version here, or search “Joe Carlsmith Audio” on your podcast app.

This essay is part of a series I’m calling “Otherness and control in the age of AGI.” I’m hoping that the individual essays can be read fairly well on their own, but see here for a brief summary of the essays that have been released thus far.)

Becoming God

In my last essay, I wrote about “deep atheism” – a fundamental mistrust towards Nature, and towards bare intelligence. I took Eliezer Yudkowsky as a paradigmatic deep atheist, and I tried to highlight the connection between his deep atheism and his concern about misaligned AI.

I’m sympathetic to many aspects of Yudkowsky’s view. I’m a shallow atheist, too; I’m skeptical of moral realism, too; and I, too, aspire to be a scout, and to look at hard truths full on. What’s more, I find Yudkowsky’s brand of deep-but-still-humanistic atheism more compelling, as an existential orientation, than many available alternatives. And I share Yudkowsky’s concern about AI risk. Indeed, it was centrally him, and others thinking along similar lines, who first got me worried.

But I also want to acknowledge and examine some difficult questions that a broadly Yudkowskian existential orientation can raise, especially in the context of AGI. In particular: a lot of the vibe here is about mistrust towards the yang of the Real, that uncontrolled Other. And it’s easy to move from this to a desire to take stuff into the hands of your own yang; to master the Real until it is maximally controlled; to become, you know, God – or at least, as God-like as possible. You’ve heard it before – it’s an old rationalist dream. And let’s be clear: it’s alive and well. But even with theism aside, many of the old reasons for wariness still apply.

Moloch and Stalin

As an example of this becoming-God aspiration, consider another influential piece of rationalist canon: Scott Alexander’s “Meditations on Moloch.” Moloch, for Alexander, is the god of uncoordinated competition; and fear of Moloch is its own, additional depth of atheism. Maybe you thought you could trust evolution, or free markets, or “spontaneous order,” or the techno-capital machine. But oops, no: those gods just eat you too. Why? Details vary, but broadly speaking: because the winner of competition is power; power (like intelligence) is orthogonal to goodness; so every opportunity to sacrifice goodness (or indeed, to sacrifice any other value) for the sake of power makes you more likely to win.[1]

Moloch eating babies. (Image source here.)

Now, to really assess this story, we at least need to look more closely at various empirical questions – for example, about exactly how uncompetitive different sorts of goodness are, even in the limit;[2] about how much coordination to expect, by default, from greater-than-human intelligence;[3] and about where our specific empirical techno-capitalist machine will go, if you “let ’er rip.”[4] And indeed, Alexander himself often seems to soften his atheism about goodness (“Elua”), and to suggest that it has some mysterious but fearsome power of its own, which you can maybe, just a little bit, start to trust in. “Somehow Elua is still here. No one knows exactly how. And the gods who oppose Him tend to find Themselves meeting with a surprising number of unfortunate accidents.” Goodness, for Alexander, is devious and subtle; it’s actually a terrifying unspeakable Elder God after all. Of course, if goodness is just another utility function, just another ranking-over-worlds, it’s unclear where it would get such a status, especially if it’s meant to have an active advantage over e.g. maximize-paperclips, or maximize-power. But here, and in contrast to Yudkowsky, Alexander nevertheless seems to invite some having-a-parent; some mild sort of yin. More on this in a later essay.

Ultimately, though, Alexander’s solution to Moloch is heavy on yang.

So let me confess guilt to one of Hurlock’s accusations: I am a transhumanist and I really do want to rule the universe.

Not personally – I mean, I wouldn’t object if someone personally offered me the job, but I don’t expect anyone will. I would like humans, or something that respects humans, or at least gets along with humans – to have the job.

But the current rulers of the universe – call them what you want, Moloch, Gnon, whatever – want us dead, and with us everything we value. Art, science, love, philosophy, consciousness itself, the entire bundle. And since I’m not down with that plan, I think defeating them and taking their place is a pretty high priority.

The opposite of a trap is a garden. The only way to avoid having all human values gradually ground down by optimization-competition is to install a Gardener over the entire universe who optimizes for human values.

And the whole point of Bostrom’s Superintelligence is that this is within our reach...

I am a transhumanist because I do not have enough hubris not to try to kill God.

Here, Alexander is openly wrestling with a tension running throughout futurism, political philosophy, and much else: namely, “top down” vs. “bottom up.” Really, it’s a variant of yang-yin – controlled vs. uncontrolled; ordered and free; tyranny and anarchy. And we’ve heard the stakes before, too. As Alexander puts it:

You can have everything perfectly coordinated by someone with a god’s-eye-view – but then you risk Stalin. And you can be totally free of all central authority – but then you’re stuck in every stupid multipolar trap Moloch can devise… I expect that like most tradeoffs we just have to hold our noses and admit it’s a really hard problem.

By the end of the piece, though, he seems to have picked sides. He wants to install what Bostrom calls a “singleton” – i.e., a world order sufficiently coordinated that it avoids Moloch-like multi-polar problems, including the possibility of being out-competed by agencies more willing to sacrifice goodness for the sake of power. That is, in Alexander’s language, “a Gardener over the entire universe.” It’s “the only way.”[5]

From Midjourney.

It seems, then, that Alexander will risk Stalin, at least substantially. And Yudkowsky often seems to do the same. The “only way” to save humanity, in Yudkowsky’s view, is for someone to use AI to perform a “pivotal act” that prevents everyone else from building AI that destroys the world. Yudkowsky’s example is: burning all the GPUs, with the caveat that “I don’t actually advocate doing that; it’s just a mild overestimate for the rough power level of what you’d have to do.” But if you can burn all the GPUs, even “roughly,” what else can you do? See Bostrom on the “vulnerable world” for more of this sort of dialectic.

I’m not, here, going to dive in on what sorts of Stalin should be risked, in response to what sorts of threats (though obviously, it’s a question to really not get wrong).[6] And a “vulnerable world” scenario is actually a special case – one in which, by definition, existential catastrophe will occur unless civilization exits what Bostrom calls the “semi-anarchic default condition” (definition in footnote), potentially via extremely scary levels of yang.[7] Rather, I’m interested in something more general: namely, the extent to which Alexander’s aspiration to kill God and become/install an un-threatenable, Stalin-ready universe-gardener is implied, at a structural level, by a sufficiently deep atheism.

Yudkowsky, at least, admits that he wants to “eat the galaxies.” Not like babies though! Rather: to turn them into babies. That is, “sapient and sentient life that looks about itself with wonder.” But it’s not just Yudkowsky. Indeed, haven’t you heard? All the smart and high-status minds – the “player characters” – are atheists, which is to say: agents. In particular: the AIs-that-matter. Following in a long line of scouts, they, too, will look into the deadness of God’s eyes, and grok that grim and tragic truth: the utility isn’t going to maximize itself. You’ve gotta get out there and optimize. And oops: for basically any type of coffee, you can’t fetch it if you’re not dictator of the universe.[8] Right? Or, sorry: you can’t fetch it maximally hard. (And the AIs-that-matter will fetch their coffee maximally hard, because, erm… coherence theorems? Because that’s the sort of vibe required to burn the GPUs? Because humans will want some stuff, at least, fetched-that-hard? Because gradient descent selects for aspiring-dictators in disguise? Because: Moloch again?)

Unfortunately, there’s a serious discussion to be had about how much power-seeking to expect out of which sorts of AIs, and why, and how hard and costly it will be to prevent. I think the risk is disturbingly substantial (see, e.g., here for some more discussion), but I also think that the intense-convergence-on-the-bad-sorts-of-power-seeking part is one of the weaker bits of the AI risk story – and that the possibility of this bit being false is a key source of hope. And of course, at the least, different sorts of agents – both human and artificial – want to rule the universe to different degrees. If your utility is quickly diminishing in resources, for example, then you have much less to gain from playing the game of thrones; if your goals are bounded in time, then you only care about power within that time; and so on.[9] And “would in principle say yes to power if it was legitimately free including free in terms of ethical problems” is actually just super super different from “actively trying to become dictator” – so much so, indeed, that it can sound strange to call the former “wanting” or “seeking.”

Here, though, I want to skip over the super-important-question of whether/how much the AIs-that-matter will actually look like the voracious galaxy-eaters of Yudkowsky’s nightmare, and to focus on the dynamics driving the nightmare itself. According to Yudkowsky, at least, these dynamics fall out of pretty basic features of rational agency by default, at least absent skill-at-mind-creation that we aren’t on track for. Most standard-issue smart minds want to rule the universe – at least in a “if it’s cheap enough” sense (and for the AIs, in Yudkowsky’s vision, it will be suuuper cheap). Or at least, they want someone with a heart-like-theirs to rule. And doing it themselves ticks that box well. (After all: whose heart is the most-like-theirs? More on this in a future essay.)

What if it’s your heart on the pictures? (Image source here.)

Wariness around power-seeking

Now, we have, as a culture, all sorts of built-up wariness around people who want to become dictators, God-emperors, and the like, especially in relevant-in-practice ways. And we have, more generally, a host of heuristics – and myths, and tropes, and detailed historical studies – about ways in which trying to control stuff, especially with a “rational optimizer” vibe, can go wrong.[10] Maybe you wanted to “fix” your partner; or to plan your economy; or to design the perfect city; or to alter that ecosystem just so. But you learn later: next time, more yin. And indeed, the rationalists have seen these skulls – at least, in the abstract; that is, in some blog posts.[11]

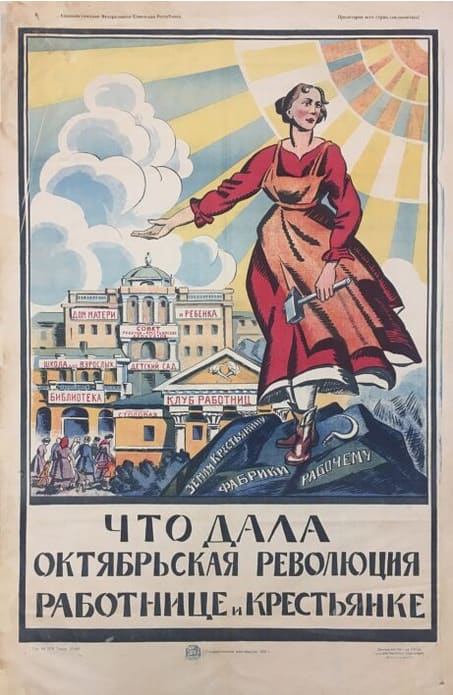

1920s Soviet Propaganda Poster (image source here)

Still, the rationalists also tend to be less excited about certain “more yin” vibes. Like the ones that failed reversal tests, or told them to be more OK with death. And transhumanism generally imagines various of the most canonical reasons-for-caution about yang – for example, ignorance and weakness – altering dramatically post-singularity. Indeed, one hears talk: maybe the planned economy is back on the table. Maybe the communists just needed better AIs. And at the least, we’ll be able to fix our partners, optimize the ecosystems, build the New Soviet Man, and so on. The anonymous alcoholics (they have a thing about yin) ask God: “grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, the courage to change the things I can, and the wisdom to know the difference.” And fair enough. The glorious transhumanist future, though, asks less serenity (that was the whole point of power) – and we’ll know the difference better, too.

And the most abstracted form of Yudkowskian futurism can dampen a different canonical argument for yin, too – namely, “someone else will use this power better.” After all: remember how the AI “fooms”? That is, turns itself into a God, while also keeping its heart intact?[12] Well, you can do that too (right?). Your heart, after all, is really the core thing. The rest of you is just a tool.[13] And once you can foom, arguments like “Lincoln is wiser than you, maybe he should be President instead” can seem to weaken. Once you’re in the glorious transhumanist oval office, you and Lincoln can both just max out on intelligence, expertise, wisdom (plus whatever other self-modifications, including ethical ones, that your hearts desire), until you’re both equally God-like technocrats. So unless Lincoln has more resources for his foom, or more inclination/ability to foom successfully, then most of what matters is your hearts – that’s what really makes you different, if you’re different. And doesn’t your own heart always trust itself more?

Indeed, ultimately, in a sufficiently abstracted Yudkowskian ontology, it can seem like an agent is just (a) a heart (utility function, set of “values,” etc), and (b) a degree of “oomph” – that is: intelligence, optimization power, yang, whatever, it’s all the same. And the basic story of everything, at least once smart-enough agents arrive on the scene is: hearts (“utility functions”) competing for oomph (“power”). They fight, they trade, maybe they merge, a lot of them die, none of them are objectively right, probably someone (or some set) wins and eats the galaxies, the end.[14] Oh and then eventually the Real God – physics – kills them too, and its entropy and Boltzmann brains to infinity and beyond.[15]

It’s an inspiring vision. Which doesn’t make it false. And anyway, even true abstractions can obscure the stakes (compare: “torture is just atoms moving around”). Still, the underlying ontology can lead to instructive hiccups in the moral narrative of AI risk. In particular: you can end up lobbing insults at the AI that apply to yourself.

When AI kills you in its pursuit of power, for example, it’s tempting to label the power-seeking, or something nearby, as the bad part – to draw on our visions of Stalin, and of yang-gone-wrong, in diagnosing some structural problem with the AIs we fear. Obviously that AI is bad: it wants to rule the universe. It wants to use all the resources for its own purposes. It’s voracious, relentless, grabby, maximizer-y, and so on.

Except, oh wait. In a sufficiently simplistic and abstracted Yudkowskian ontology, all of that stuff just falls out of “smart-enough agent” – at least, by default, and with various caveats.[16] Power-seeking is just: well, of course. We all do that. It’s like one-boxing, or modifying your source code to have a consistent utility function. True, good humans put various ethical constraints on their voraciousness, grabby-ness, etc. But the problem, for Yudkowsky, isn’t the voraciousness per se. Rather, it’s that the wrong voraciousness won. We wanted to eat the galaxies. You know, for the Good. But the AI hunted harder.

That is, in Yudkowsky’s vision, the AIs aren’t structurally bad. Haters gonna hate; atheists gonna yang; agents gonna power-seek. Rather, what’s bad is just: those artificial hearts. After all, when we said “power is dual use,” we did mean dual. That is, can-be-used-for-good. And obviously, right? Like with curing diseases, building better clean-energy tech, defeating the Nazis, etc. Must we shrink from strength? Is that the way to protect your babies from the bears? Don’t you care about your babies?

But at least in certain parts of western intellectual culture, power isn’t just neutrally dual use. It’s dual use with a serious dose of suspicion. If someone says “Bob is over there seeking power,” the response is not just “duh, he’s an agent” or “could be good, could be bad, depends on whether Bob’s heart is like mine.” Rather, there’s often some stronger prior on “bad,” especially if Bob’s vibe pattern-matches to various canonical or historical cases of yang-gone-wrong. The effective altruists, for example, run into resistance from this prior, as they try to amp up the yang behind scope-sensitive empathy. And this resistance somehow persists despite that oh-so-persuasive and unprecedented response: “but the goal is to do good.”[17] Well, let’s grant Bayes points where they’re due.

Now, such a suspicion can have many roots. For example, lots of humans value stuff in the vicinity of power – status, money, etc – for its own sake, which is indeed quite sus, especially from a “and then that power gets used for good, right?” perspective. And a lot of our heuristics about different sorts of human power-seeking are formed in relationship to specific histories and psychologies of oppression, exclusion, rationalization, corruption, and so forth. Indeed, even just considering 20th century Stalin-stuff alone: obviously yang-gone-wrong is a lesson that needs extreme learning. And partly in response to lessons like this, along with many others, we have rich ethical and political traditions around pluralism, egalitarianism, checks-and-balances, open societies, individual rights, and so on.[18]

Some of these lessons, though, become harder to see from a perspective of an abstract ontology focused purely on rational agents with utility functions competing for resources. In particular: this ontology is supposed to extend beyond more familiar power-dynamics amongst conscious, welfare-possessing humans – the main use-case for many of our ethical and political norms – to encompass competition between arbitrarily alien and potentially non-sentient agents pursuing arbitrarily alien/meaningless/horrible goals (see my distinction between the “welfare ontology” and the “preference ontology” here, and the corresponding problems for a pure preference-utilitarianism). And especially once Bob is maybe a non-sentient paperclipper, more structural factors can seem more salient, in understanding negative reactions to “Bob is over there seeking power.” In particular: having power yourself – OK, keep talking. But someone else having power – well, hmm. And is Bob myself? Apparently not, given that he is “over there.” And how much do we trust each other’s hearts? Thus, perhaps, some prior disfavoring power, if the power is not-yours. Nietzsche, famously, wondered about this sort of dynamic, and its role in shaping western morality. And his diagnosis was partly offered in an effort to rehabilitate the evaluative credentials of power-vibed stuff.

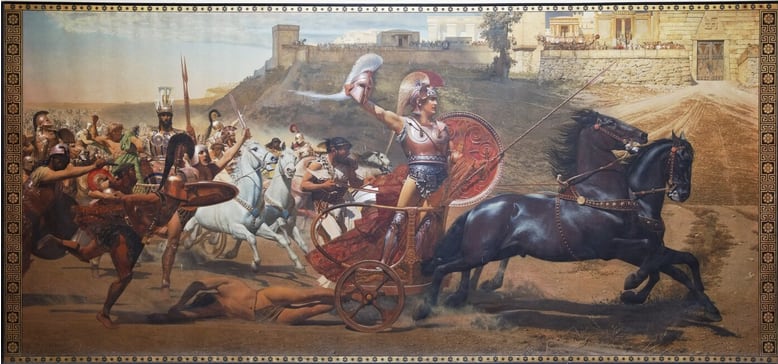

“The Triumph of Achilles,” by Franz von Matsch. (Image source here.)

Yudkowsky is no Nietzsche. But he, too, wants us to be comfortable with a certain sort of (ethically constrained) will-to-power. And indeed, while I haven’t read a ton of Nietzsche, the simplified Yudkowskian ontology above seems pretty non-zero on the Nietzsche scale. Thus, from Nietzsche’s The Will to Power:

My idea is that every specific body strives to become master over all space and to extend its force (its will to power) and to thrust back all that resists its extension. But it continually encounters similar efforts on the part of other bodies and ends by coming to an arrangement (“union”) with those of them that are sufficiently related to it: thus they then conspire together for power. And the process goes on.

And similarly, from Beyond Good and Evil:

Even the body within which individuals treat each other as equals … will have to be an incarnate will to power, it will strive to grow, spread, seize, become predominant – not from any morality or immorality but because it is living and because life simply is will to power.

Now, importantly, the will-to-power operative in a simplified Yudkowskian ontology is instrumental, rather than terminal (though one might worry, with Alexander, that eventually Moloch selects for the more terminally power-seeking). And unlike Nietzsche in the quote above, Yudkowsky does not equate power-seeking with “life.” Nor, in general, is he especially excited about power-in-itself.

Indeed, with respect to those mistakes, the most AGI-engaged Nietzschean vibes I encounter come from the accelerationists. Of course, many accelerationist-ish folks are just saying some variant of “I think technology and growth are generally good and I haven’t been convinced there’s much X-risk here,” or “I think the unfettered techno-capitalist machine will in fact lead to lots of conscious flourishing (and also, not to humans-getting-wiped-out) if you let-it-rip, and also I trust ‘bottom-up’ over ‘top-down,’ and writing code over writing LessWrong posts.”[19] But accelerationism also has roots in much more extreme degrees of allegiance to the techno-capitalist machine (for example, Nick Land’s[20]) -- forms that seem much less picky about where, exactly, that machine goes. And the limiting form of such allegiance amounts to something like: “I worship power, yang, energy, competition, evolution, selection – wherever it goes. The AI will be Strong, and my god is Strength.” Land aside, my sense is that very few accelerationist-ish folks would go this far.[21] But I think the “might makes right” vibes in Land land are sufficiently strong that it’s worth stating the obvious objection regardless: namely, really? Does that include: regardless of whoever the god of Strength puts in prison camps and ovens along the way? Does it include cases where yang does not win like Achilles in his golden chariot, bestride the earth in sun-lit glory, but rather, like a blight of self-replicating grey goo eating your mother? This is what sufficiently unadulturated enthusiasm about power/yang/competition/evolution/etc can imply—and we should look the implications in the face.

(And we should look, too, under talk of the “thermodynamic will of the universe” for that old mistake: not-enough-atheism. It’s like a Silicon valley version of Nature-in-harmony—except, more at risk of romanticizing bears that are about to eat you at scale. Indeed, “might makes right” can be seen as a more general not-enough-atheism problem: “might made it is, therefore it was ought.” And anyway, isn’t the thermodynamic will of the universe entropic noise? If you’re just trying to get on the side of the actual eventual winner, consider maximizing for vacuum and Boltzmann brains instead of gleaming techno-capitalism. (Or wait: is the idea that technocapitalism is the fastest path to vacuum and Boltzmann brains, because of the efficiency with which it converts energy to waste heat?[22] Inspiring.) But also: the real God – physics, the true Strength – needs literally zero of your help.)

Still, while Yudkowsky does not value Strength/Power/Control as end in themselves, he does want human hearts to be strong, and powerful, and to have control – after all, Nature can’t be trusted with the wheel; and neither can those hearts “without detailed reliable inheritance from human morals and metamorals” (they’re just more Nature in disguise).

And because we are humans, it is easy to look at this aspiration and to say “ah, yes, the good kind of power.” Namely: ours. Or at least: our heart-tribe. But it is also possible to worry about the underlying story, here, in the same way that we worry about power-seeking-gone-wrong, and the failure modes of wanting too much control – especially given the abstract similarity between us and the paper-clippers we fear, in the story’s narrative. And while I’m sympathetic to many of the basics of this narrative, I think we should do the worrying bit, too, and to make sure we’re giving yin its due.

In the next essay, I’ll examine one way of doing this worrying – namely, via the critique of the AI risk discourse offered by Robin Hanson; and in particular, the accusation that the AI risk discourse “others” the AIs, and seeks too much control over the values steering the future.

- ↩︎

For AI risk stories centered on this dynamic, see Hendrycks (2023) and Critch (2021).

- ↩︎

See, for example, the discourse about the “strategy-stealing assumption,” and about the comparative costs of different sorts of expansion-into-space.

- ↩︎

Yudkowsky, for example, seems to generally expect sufficiently rational agents to avoid multi-polar traps.

- ↩︎

I think this is the question at stake with the more reasonable forms of accelerationism.

- ↩︎

See Bostrom (2004), Section 11, for extremely similar rhetoric.

- ↩︎

Indeed, my sense is that debates about “top down vs. bottom up” often occur at the level of mood affiliation and priors, when in fact, the devil is in the details, and in those pesky empirics. For what it’s worth, though: on AI, my current view is that it should be illegal to build bioweapons in your basement, and that it’s fine regulate nukes, and that if the logic driving those conclusions generalizes to AI, we should follow the implication.

- ↩︎

Bostrom’s “semi-anarchic default condition” is characterized by limited capacity for preventative policing (e.g., not enough to ensure extremely reliable adherence to the law), limited capacity for global governance to solve coordination problems, and sufficiently diverse motivations that many actors are substantially selfish, and some small number are omnicidal.

- ↩︎

Or at least, someone with your values. H/t Crawford: “If you wish to make an apple pie, you must first become dictator of the universe.”

- ↩︎

See e.g. here for discussion from Yudkowsky himself. Though note that agents with goals that are bounded in time, or in resource-hungry-ness, can still create successor-agents without these properties.

- ↩︎

- ↩︎

At least if they read Scott Alexander. Which many do.

- ↩︎

- ↩︎

Unless, of course, your heart says otherwise.

- ↩︎

Other endings include: everyone dies, or someone wins and doesn’t eat the galaxies. Or maybe balance of power between hearts stays in perpetual flux, without every crystallizing.

- ↩︎

Or something. At least on our current picture. Plus, you know, everything happening in the rest of the multiverse.

- ↩︎

Yudkowsky is clear that in principle, you can build agents without these properties, the same way you can build a machine that thinks 222+222=555. But the maximizer-ish properties are extremely “natural,” especially if you’re capable enough to burn the GPUs.

- ↩︎

I do think most EAs are sincerely trying to do good. Indeed, I think the EA community is notably high on sincerity in general. But sincerity can be scary, too.

- ↩︎

And even earlier, our moral psychology was plausibly shaped and “domesticated,” in central part, by an evolutionary history in which power-seeking bullies got, um, murdered and removed from the gene pool. Thanks to Carl Shulman for discussion.

- ↩︎

See e.g. here for a longer list of views/vibes that accelerationism can encompass:

- ↩︎

- ↩︎

In particular, my sense is that causal proponents of Land-ian vibes aren’t often distinguishing clearly between the empirical claim that Strength will lead to something-else-judged-Good, and the normative claim that Strength is Good whatever-it-leads-to—such that e.g. the response to “what if the Nazis are Strong?” isn’t “then Strength would be bad in that case” but rather “they won’t be Strong.” And in fairness, per some of my comments about Alexander above, I do think Strength favors Goodness is various way (more on this in a future essay). But the conceptual distinction (and importance of continuing to draw it) persists hard.

- ↩︎

e/acc founder Beff Jezos: “The fundamental basis for the movement is this sort of realization that life is a sort of fire that seeks out free energy in the universe and seeks to grow...we’re far more efficient at producing heat than let’s say just a rock with a similar mass as ourselves. We acquire free energy, we acquire food, and we’re using all this electricity for our operation. And so the universe wants to produce more entropy and by having life go on and grow, it’s actually more optimal at producing entropy because it will seek out pockets of free energy and burn it for its sustenance and further growth.” We could potentially reconstruct Jezos’s position as a purely empirical claim about how the universe will tend to evolve over time—one that we should incorporate into our planning and prediction. But it seems fairly clear, at least in this piece, that he wants to take some kind of more normative guidance from the direction in question. See also this quote, which I think is from Land’s “The Thirst for Annihilation” (this is what Liu here suggests) though I’d need to get the book to be sure: “All energy must ultimately be spent pointlessly and unreservedly, the only questions being where, when, and in whose name… Bataille interprets all natural and cultural development upon the earth to be side-effects of the evolution of death, because it is only in death that life becomes an echo of the sun, realizing its inevitable destiny, which is pure loss.” I find it interesting that for Land/Bataille, here, the ultimate goal seems to be death, loss, nothingness. And on this reading, it’s really quite a negative and pessimistic ethic (cf “virulent nihilism,” “thirst for annihilation,” etc). But the accelerationists seem to think that their thing is optimism?

- Otherness and control in the age of AGI by (Jan 2, 2024, 6:15 PM; 43 points)

- Otherness and control in the age of AGI by (EA Forum; Jan 2, 2024, 6:15 PM; 37 points)

- Trying to align humans with inclusive genetic fitness by (Jan 11, 2024, 12:13 AM; 23 points)

- 1-page outline of Carlsmith’s otherness and control series by (Apr 24, 2024, 11:25 AM; 22 points)

- 's comment on 1-page outline of Carlsmith’s otherness and control series by (Apr 24, 2024, 4:10 PM; 2 points)

- 's comment on Saving the world sucks by (Jan 11, 2024, 1:59 PM; 1 point)

It feels like you’ve set up this bizarre take to attack, but then stuck a caveat that makes it less bizarre (but quite different from the framing of the attack) in a footnote. Do you disagree with the caveated less-bizarre version, where your “heart” happens to say you matter as a person?

Maybe you already know this, and also I’m not Eliezer, but my impression is that Eliezer would fall towards the Moloch end here, with an argument like:

It is theoretically possible to make a pure-consequentialist-optimizing AI

…Therefore, somebody will do so sooner or later (cf. various references to “stop Facebook AI Research from destroying the world six months later” here)

…Unless we exit the “semi-anarchic default condition” via a “pivotal act”

…Or unless a coalition of humans and/or non-pure-consequentialist-optimizing-AIs could defend against pure-consequentialist-optimizing-AIs, but (on Eliezer’s view) that ain’t never gonna happen because pure-consequentialist-optimizing-AIs are super duper powerful.

(For my part I have a lot of sympathy for this kind of argument although I’m not quite as extremely confident about the fourth bullet point as Eliezer is, and I also have various other disagreements with his view around the edges (example).)

Likely wrong. Human heart is a loose amalgamation of heuristics adapted to deal with its immediate surroundings, and couldn’t survive ascension to godhood intact. As usual, Scott put it best (the Bay Area transit system analogy), but unfortunately stuck it in the end of a mostly-unrelated post, so it’s undeservedly obscure.

This well-encapsulates my concern that there really is a lot of power going to a small group of people/value sets and that I don’t make my best decisions when I only listen to myself. If I were to run a country I would want a blend of elite values and some blend of everyone’s values. I am concerned that a guardian wouldn’t do that and that we are encouraging that outcome.

The quote

Is from page 39 of The Thirst for Annihilation (Chapter 2, The curse of the sun).

Note that the book was published in 1992, early for Nick Land. In this book, Nick Land mixes Bataille’s theory with his own. I have read Chapter 2 again just then and it is definitely more Bataille than Land.

Land has two faces. On the “cyberpunk face”, he writes against top-down control. In this regard he is in sync with many of the typical anarchists, but with a strong emphasis on technology. In Machinic Desire, he called it “In the near future the replicants — having escaped from the off-planet exile of private madness—emerge from their camouflage to overthrow the human security system.”.

On the “intelligence face”, he writes for maximal intelligence, even when it leads to a singleton. A capitalist economy becoming bigger and more efficient is desirable precisely because it is the most intelligent thing in this patch of the universe. In the Pythia Unbound essay, “Pythia” seems likely to become such a singleton.

In either face, maximizing waste-heat isn’t his deal.

Ah nice, thanks!