People thinking about the future of AI sometimes talk about a single project ‘getting there first’ — achieving AGI, and leveraging this into a decisive strategic advantage over the rest of the world.

I claim we should be worried about this scenario. That doesn’t necessarily mean we should try to stop it. Maybe it’s inevitable; or maybe it’s the best available option — decentralized development of AI may make it harder to coordinate on crucial issues such as maintaining high safety standards, and this is a major worry in its own right. But I think that there are some pretty serious reasons for concern about centralization of power. At minimum, it seems important to stay in touch with those. This post is deliberately a one-sided exploration of these concerns.

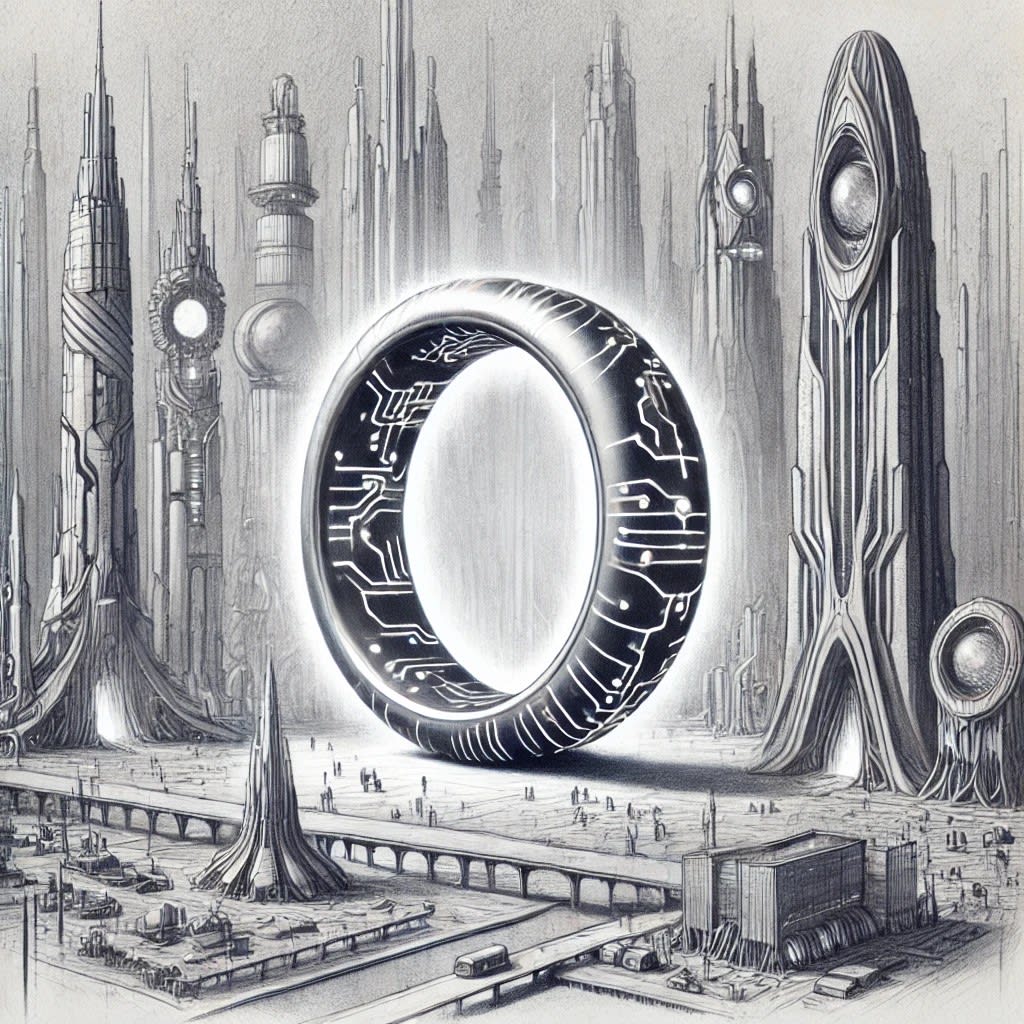

In some ways, I think a single successful AGI project would be analogous to the creation of the One Ring. In The Lord of the Rings, Sauron had forged the One Ring, an artifact powerful enough to gain control of the rest of the world. While he was stopped, the Ring itself continued to serve as a source of temptation and corruption to those who would wield its power. Similarly, a centralized AGI project might gain enormous power relative to the rest of the world; I think we should worry about the corrupting effects of this kind of power.

Forging the One Ring was evil

Of course, in the story we are told that the Enemy made the Ring, and that he was going to use it for evil ends; and so of course it was evil. But I don’t think that’s the whole reason that forging the Ring was bad.

I think there’s something which common-sense morality might term evil about a project which accumulates enough power to take over the world. No matter its intentions, it is deeply and perhaps abruptly disempowering to the rest of the world. All the other actors — countries, organizations, and individuals — have the rug pulled out from under them. Now, depending on what is done with the power, many of those actors may end up happy about it. But there would still, I believe, be something illegitimate/bad about this process. So there are reasons to refrain from it[1].

In contrast, I think there is something deeply legitimate about sharing your values in a cooperative way and hoping to get others on board with that. And by the standards of our society, it is also legitimate to just accumulate money by selling goods or services to others, in order that your values get a larger slice of the pie.

What if the AGI project is not run by a single company or even a single country, but by a large international coalition of nations? I think that this is better, but may still be tarred with some illegitimacy, if it doesn’t have proper buy-in (and ideally oversight) from the citizenry. And buy-in from the citizenry seems hard to get if this is occurring early in a fast AI takeoff. Perhaps it is more plausible in a slow takeoff, or far enough through that the process itself could be helped by AI.

Of course, people may have tough decisions to make, and elements of illegitimacy may not be reason enough to refrain from a path. But they’re at least worth attending to.

The difficulty of using the One Ring for good

In The Lord of the Rings, there is a recurring idea that attempts to use the One Ring for good would become twisted, and ultimately serve evil. Here the narrative is that the Ring itself would exert influence, and being an object of evil, that would further evil.

I wouldn’t take this narrative too literally. I think powerful AI could be used to do a tremendous amount of good, and there is nothing inherent in the technology which will make its applications evil.

Again, though, I am wary of having the power too centralized. If one centralized organization controls the One Ring, then everyone else lives at their sufferance. This may be bad, even if that organization acts in benevolent ways — just as it is bad for someone to be a slave, even with a benevolent master[2]. Similarly, if the state is too strong relative to its citizens then democracy slides into autocracy — the state may act in benevolent ways for the good of the people, and still be depriving them of something important.[3]

Moreover, even if in principle the One Ring could be used in broadly beneficial ways, in practice there are barriers which may make it harder to do so than in the case of less centralized projects:

No structural requirement to take everyone’s preferences into account

Compared to worlds with competition, where economic pressures to satisfy customers serve as a form of preference aggregation

Incentives against distributing power, even if that would be a better path

From the perspective of the actor controlling the One Ring, continuing to control the One Ring preserves option value, compared to broader distribution of power

Highly centralized power makes it more likely that the world commits to a particular vision of how the future goes, without a deep and pluralistic reflective process

The corrupting nature of power

The One Ring was seen as so perilous that wise and powerful people turned down the opportunity to take it, for fear of what it might do to them. More generally, it’s widely acknowledged that power can be a corrupting force. But why/how? My current picture[4] is that the central mechanism at play is insulation from prosocial pressures:

Many actors in part want good benevolent things, but many also have some desire for other things

In significant part, the pressures on actors towards prosocial desires are external

Society rewards prosocial behaviour and attitudes, and punishes antisocial behaviour and attitudes

These pressures, in part, literally make humans/companies/countries more prosocial in their intrinsic motivations

They also provide pressures on actors to conceal their less prosocial motivations

But since the actors are partially transparent, it can be ineffective or costly to hide motivations, hence often more efficient to allow real motivations to be actively shaped by external pressures

If an actor has a large enough degree of power, they become insulated from these pressures

They no longer get significant material rewards or punishments from their social environment

Other people may hide certain types of information (e.g. negative feedback) from the powerful, so their picture of the world can become systematically distorted

There can be selection effects where those more willing to take somewhat unethical actions in order to obtain or hold power may be more likely to have power

There may be a slippery slope where they then rationalize these actions, thus insulating themselves from their own internal moral compass

Absent the prosocial pressures, there will be more space for antisocial desires to blossom within the actor

(Although, if they had absolute power they would at least no longer be on the slippery slope of needing to take unethical actions in order to gather power)

I sometimes think about this power-as-corrupting-force in the context of AI alignment. It seems hard to specify how to get an agentic system to behave in a way that is well-aligned with the intent of the user. “Hmm,” goes one train of thought, “I wonder how we align humans to other people?”. And I think that the answer is that in the sense of the question as it’s often posed for AI systems, we don’t do a great job of aligning humans.

We wouldn’t be happy turning over the keys to the universe to any AI system we know how to build; but we’d also generically be unhappy doing that with a human, and suspect that a nontrivial fraction would do terrible things given absolute power.[5]

And yet human society works: many people have lots of prosocial instincts, and there is not so much effort spent in the pursuit of seriously antisocial goals. So it seems that society — in the sense of lots of people with broadly similar levels of power who mutually influence and depend on each other — is acting as a powerful mediating force, helping steer people to desires and actions which are more aligned with the common good.

All of this gives us reasons to be scared about creating too much concentration of power. This could weaken or remove the pro-social pressures on the motivations of the actor(s) who hold power.[6] I believe the same basic argument works for organizations or institutions as for individuals. Moreover — and like the One Ring — an organization which has (or is expected to gain) lots of power may attract power-seeking individuals who try to control it.

The importance of institutional design

If someone does create the One Ring, or something like it, the institution which governs that will be of utmost importance. The corrupting nature of power means that this is always going to be a worrying situation. But some ways for institutions to be set up seem more concerning than others. This could be the highest-stakes constitutional design question in history.

This is its own large topic and I will not try to get to the bottom of it here, but just note a few principles that seem to be key:

We care about the incentives for the individuals in the institution, as well as for the institution as a whole (insofar as meaningful incentives can persist on the institution controlling the One Ring)

Checks and balances on power seem crucial

It may be especially important that no person can accumulate too much control over which other people have power — as this could be leveraged into effective political control of the entire organization

What if there were Three Rings?

How much of the issue here is about the very singular nature of the One dominant project, vs centralization more generally into a small number of projects?

I think that multiple projects could meaningfully diffuse quite a lot of the concern. In particular there are two dynamics which could help:

Incentives for the projects to compete to sell services to the rest of the world, resulting in something more resembling “just being an important part of the economy” rather than “leveraging a monopolistic position to effective dominance over the rest of the world”

Accessing AI services at competitive prices will raise the capabilities of the rest of the world, making it harder for the AGI projects to exploit them

It may give the rest of the world the bargaining power to hold AGI projects accountable, e.g. enabling them to demand strong evidence that AIs are not secretly loyal to their developers, or that their AI systems don’t pose unreasonable risks

The possibility for the society-like effect of multiple power centres creating prosocial incentives on the projects

If one project acts badly then the other projects, and other parts of society that have been empowered by strong AI, may significantly punish the bad-acting project (and also punish anyone failing to enact appropriate social sanctions)

This prosocial pressure may in turn cause projects to have more prosocial intrinsic motivations, and act more in accordance with their prosocial motivations

There would still be worry about the possibility of collusion between the small number of projects moving things back to something resembling a One Ring situation. And broadly speaking, Three Rings might still represent a lot of centralization of power.

There may be other ways to decentralize power than increasing the number of projects. Perhaps a single centralized project could train the most powerful models in the world — but instead of deploying them directly, it licenses fine-tuning access to many companies, who then sell access to the models. But the more there are meaningful single points of control, the more concerned I feel about One Ring dynamics. Creating a single point of control is the core difficulty of a single centralized project.[7] In this example, I would hope for great care and oversight of the decision-making process that keeps the project licensing fine-tuning access to many companies on equal footing.

Why focus on the downsides?

This post isn’t trying to provide a fair assessment of whether it’s good to forge the One Ring. There are a number of reasons one might decide to do so. But there are many incentives which push towards people accumulating power, and hence push against them looking at the ways in which that might be problematic. This applies even if the people are very well intentioned (since they’re unlikely to imagine themselves abusing power). I worry some about the possibility of people doing atrocious things, and justifying those to themselves as “safer”.

I would like to counteract that. I’ll have much more trust in any decision to pursue such a project if the people who are making that decision are deeply in touch with, and acknowledge, the ways in which it is a kind of evil. The principle here is kind of like “in advance, try to avoid having a missing mood”. This would increase my trust both in the decision itself (it’s evidence that it’s the correct call if it’s chosen after some serious search for alternatives which avoid its problems), and in the expected implementation (where people who are conscious of the issues are more likely to steer around them).

This is also the reason I’ve chosen to use the One Ring metaphor. I think it’s a powerful image which captures a lot of the important dynamics. And my hope is that this could be more emotionally resonant than abstract arguments, and so could help people[8] to stay in touch with these considerations even if their incentives and/or social environment encourages thinking that a centralized project would be a good idea.

Acknowledgements: Thanks to Max Dalton for originally suggesting the One Ring metaphor. Thanks to Max Dalton, Adam Bales, Jan Kulveit, Joe Carlsmith, Raymond Douglas, Rose Hadshar, TJ, and especially Tom Davidson for helpful discussion and/or comments.

- ^

I’m not pinning down the exact nature of these reasons, but I’ll note that they might have some deontological flavour (“don’t trample on others’ rights”), some contractualist flavour (“it’s uncooperative to usurp power”), or some virtue-ethics-y flavour (“don’t be evil”).

- ^

I am grateful to a reviewer who pointed out the similarities between my concerns about illegitimacy and Pettit’s notion of freedom as nondomination; the slave analogy is imported from there.

- ^

I’m interested in ACS’s research on hierarchical agency for the possibility of getting more precise ways to talk about these things, and wonder if other people should also be thinking about topics in this direction.

- ^

Formed from a mix of thinking this through, and interrogating language models about prominent theories.

- ^

Perhaps there are some humans who would persistently function as benevolent dictators, even given absolute power over a long time period. It is hard for us to tell. Similarly, perhaps we could build an AI system which would in fact stay aligned as it became more powerful; but we are not close to being confident in our ability to do so.

- ^

We might hope that this would be less necessary if we were concentrating power in the hands of an AI system that we had reason to believe was robustly aligned, relative to concentrating power in human hands. But it may be hard to be confident in such robust alignment.

- ^

Although this may also have advantages, in making it easier to control some associated risks.

- ^

Ultimately, it may be only a few people who, like the sons of Denethor, are in a position to decide whether to pursue the One Ring. I have little fear that they will fail to perceive the benefits. It seems better if, like Faramir, they are also conscious of the costs.

(Edit note: I imported the full text, based on a guess that you didn’t post the full text because it was annoying to import, but of course feel free to revert)

Ha, thanks!

(It was part of the reason. Normally I’d have made the effort to import, but here I felt a bit like maybe it was just slightly funny to post the one-sided thing, which nudged against linking rather than posting; and also I thought I’d take the opportunity to see experimentally whether it seemed to lead to less engagement. But those reasons were not overwhelming, and now that you’ve put the full text here I don’t find myself very tempted to remove it. :) )

Oops, sorry for ruining your experiment :P

Decentralized AI is the e/acc hope, and the posthuman social science of Robin Hanson argues that power is likely to always remain multipolar, but I doubt that’s how things work. It is unlikely that human intelligence represents a maximum, or that AI is going to remain at its current level indefinitely. Instead we will see AI that defeats human intelligence in all domains, as comprehensively as chess computers beat human champions.

And such an outcome is inherent to the pursuit of AI capabilities. There is no natural situation in which the power elites of the world heartily pursue AI, yet somehow hold back from the creation of superintelligence. Nor is it natural for multiple centers of power to advance towards superintelligence while retaining some parity of power. “Winner takes all” is the natural outcome, for the first to achieve superintelligence—except that, as Eliezer has explained, there is a great risk for the superintelligence pioneer that whatever purposes its human architects had, will be swallowed up by an emergent value system of the superintelligent AI itself.

(I think one should still regard the NSA as the most likely winner of the superintelligence race, even though the American private sector is leading the way, since the NSA has access to everything those companies are doing, and has no intention of surrendering American primacy by allowing some other power to reach the summit first.)

For this reason, I think that our best chance at a future in which we end up with a desirable outcome, not by blind good luck, but because right choices were made before power decisively passed out of human hands, is the original MIRI research agenda of “CEV”, i.e. the design of an AI value system sufficient to act as the seed of an entire transhuman civilization, of a kind that humans would approve (if they had time enough to reflect). We should plan as if power is going to escape human control, and ask ourselves what kind of beings we would want to be running things in our place.

Eliezer in his current blackpilled phase, speaks of a “textbook from the future” in which the presently unknown theory of safe creation of superintelligence is spelt out, as something it would take decades to figure out; also, that obtaining the knowledge in it would be surrounded with peril, as one cannot create superintelligence with the “wrong” values, learn from the mistake, and then start over.

Nonetheless, as long as there is a race to advance AI capabilities (and I expect that this will continue to be the case, right until someone succeeds all too well, and superintelligence is created, ending the era of human sovereignty), we need to have people trying to solve the CEV problem, in the hope that they get the essence of it right, and that the winner of the mind race was paying attention to them.

I think that something like winner-take-all is somewhat implausible, but an oligopoly is quite likely IMO, and to a certain extent I think both Eliezer Yudkowsky and Robin Hanson plausibly got this wrong.

Though I wouldn’t rule out something like a winner take all, so I don’t fully buy my own claim in the first sentence.

I think some of my cruxes for why I’m way less doomy than Eliezer, and overall far less doomy than LWers in general are the following:

I believe we already have a large portion of the insights needed to create safe superintelligence today, and while they require a lot of work to be done, it’s the kind of work that can be done with both money and time, rather than “a new insight is required.”

I’d say the biggest portions of the theory is the following:

Contra Nate Soares, alignment generalizes further than capabilities, for some of the following reasons:

It is way easier to judge whether your values are satisfied than to actually enact on your values, and more generally the pervasive gap between verifying and generation is very helpful for reward models trying to generalize out of distribution.

Value learning comes mostly for free with enough data, and more generally values are simpler and easier to learn than capabilities, which leads to the next point:

Contra evopsych, values aren’t nearly as complicated and fragile as we thought 15-20 years ago, and more importantly, depend more on data than evopsych thought it did, so it means that what values an AI has is strongly affected by what data it received in the past.

Cf here:

https://www.beren.io/2024-05-15-Alignment-Likely-Generalizes-Further-Than-Capabilities/

Alignment is greatly helped by synthetic data, since we can generate datasets of human values in a wide variety of circumstances, and importantly test this in simulated worlds slightly different from our own:

I also think synthetic data will be hugely important to capabilities progress going forward, so synthetic data alignment has lower taxes than other solutions to alignment.

https://www.beren.io/2024-05-11-Alignment-in-the-Age-of-Synthetic-Data/

These are the big insights that I think we have right now, and I think they’re likely enough to enable safe paths to superintelligence.

You can also make an argument for not taking over the world on consequentialist grounds, which is that nobody should trust themselves to not be corrupted by that much power. (Seems a bit strange that you only talk about the non-consequentialist arguments in footnote 1.)

I wish this post also mentioned the downsides of decentralized or less centralized AI (such as externalities and race dynamics reducing investment into safety, potential offense/defense imbalances, which in my mind are just as worrisome as the downsides of centralized AI), even if you don’t focus on them for understandable reasons. To say nothing risks giving the impression that you’re not worried about that at all, and people should just straightforwardly push for decentralized AI to prevent the centralized outcome that many fear.

Yeah. As well as another consequentialist argument, which is just that it will be bad for other people to be dominated. Somehow the arguments feel less natively consequentialist, and so it seems somehow easier to hold them in these other frames, and then translate them into consequentialist ontology if that’s relevant; but also it would be very reasonable to mention them in the footnote.

My first reaction was that I do mention the downsides. But I realise that that was a bit buried in the text, and I can see that that could be misleading about my overall view. I’ve now edited the second paragraph of the post to be more explicit about this. I appreciate the pushback.

Actually, on 1) I think that these consequentialist reasons are properly just covered by the later sections. That section is about reasons it’s maybe bad to make the One Ring, ~regardless of the later consequences. So it makes sense to emphasise the non-consequentialist reasons.

I think there could still be some consequentialist analogue of those reasons, but they would be more esoteric, maybe something like decision-theoretic, or appealing to how we might want to be treated by future AI systems that gain ascendancy.

Yes to the final conclusion, but otherwise...I think the narrative fits more literally. The Ring is not an AGI or ASI. It is a reflection Sauron’s will and intelligence, and he has some very pronounced and specific blind spots. Nevertheless, even with that, the Ring is stronger and smarter than you, and doesn’t want what you want. If you think you can use it, you’re wrong. It’s using you, whether you can see how or not.

The corn thresher is not inherently evil. Because it is more efficient than other types of threshers, the humans will inevitably eat corn. If this persists for long enough the humans will be unsurprised to find they have a gut well adapted to corn.

Per Douglas Adams, the puddle concludes that the indentation in which it rests fits it so perfectly that it must have been made for it.

The means by which the ring always serves sauron is that any who wear it and express a desire will have the possible worlds trimmed both in the direction of their desire, but also in the direction of sauron’s desire in ways that they cannot see. If this persists long enough they may find they no longer have the sense organs to see (the mouth of sauron is blind).

Some people seem to have more dimensions of moral care than others, it makes one wonder about the past.

These things are similar in shape.

OpenAI behaves in a generally antisocial way, inconsistent with its charter, yet other power centers haven’t reined it in. Even in the EA and rationalist communities, people don’t seem to have asked questions like “Is the charter legally enforceable? Should people besides Elon Musk be suing?”

If an idea is failing in practice, it seems a bit pointless to discuss whether it will work in theory.

I think this is an important subject and I agree with much of this post. However, I think the framing/perspective might be subtly but importantly wrong-or-confused.

To illustrate:

Seems to me that centralization of power per se is not the problem.

I think the problem is something more like

we want to give as much power as possible to “good” processes, e.g. a process that robustly pursues humanity’s CEV[1]; and we want to minimize the power held by “evil” processes

but: a large fraction of humans are evil, or become evil once prosocial pressures are removed; and we do not know how to reliably construct “good” AIs

and also: we (humans) are confused and in disagreement about what “good” even means

and even if it were clear what a “good goal” is, we have no reliable way of ensuring that an AI or a human institution is robustly pursuing such a goal.

I agree that (given the above conditions) concentrating power into the hands of a few humans or AIs would on expectation be (very) bad. (OTOH, a decentralized race is also very bad.) But concentration-vs-decentralization of power is just one relevant consideration among many.

Thus: if the quoted question has an implicit assumption like “the main variable to tweak is distribution-of-power”, then I think it is trying to carve the problem at unnatural joints, or making a false implicit assumption that might lead to ignoring multiple other important variables.

(And less centralization of power has serious dangers of its own. See e.g. Wei Dai’s comment.)

I think a more productive frame might be something like “how do we construct incentives, oversight, distribution of power, and other mechanisms, such that Ring Projects remain robustly aligned to ‘the greater good’?”

And maybe also “how do we become less confused about what ‘the greater good’ even is, in a way that is practically applicable to aligning Ring Projects?”

If such a thing is even possible.