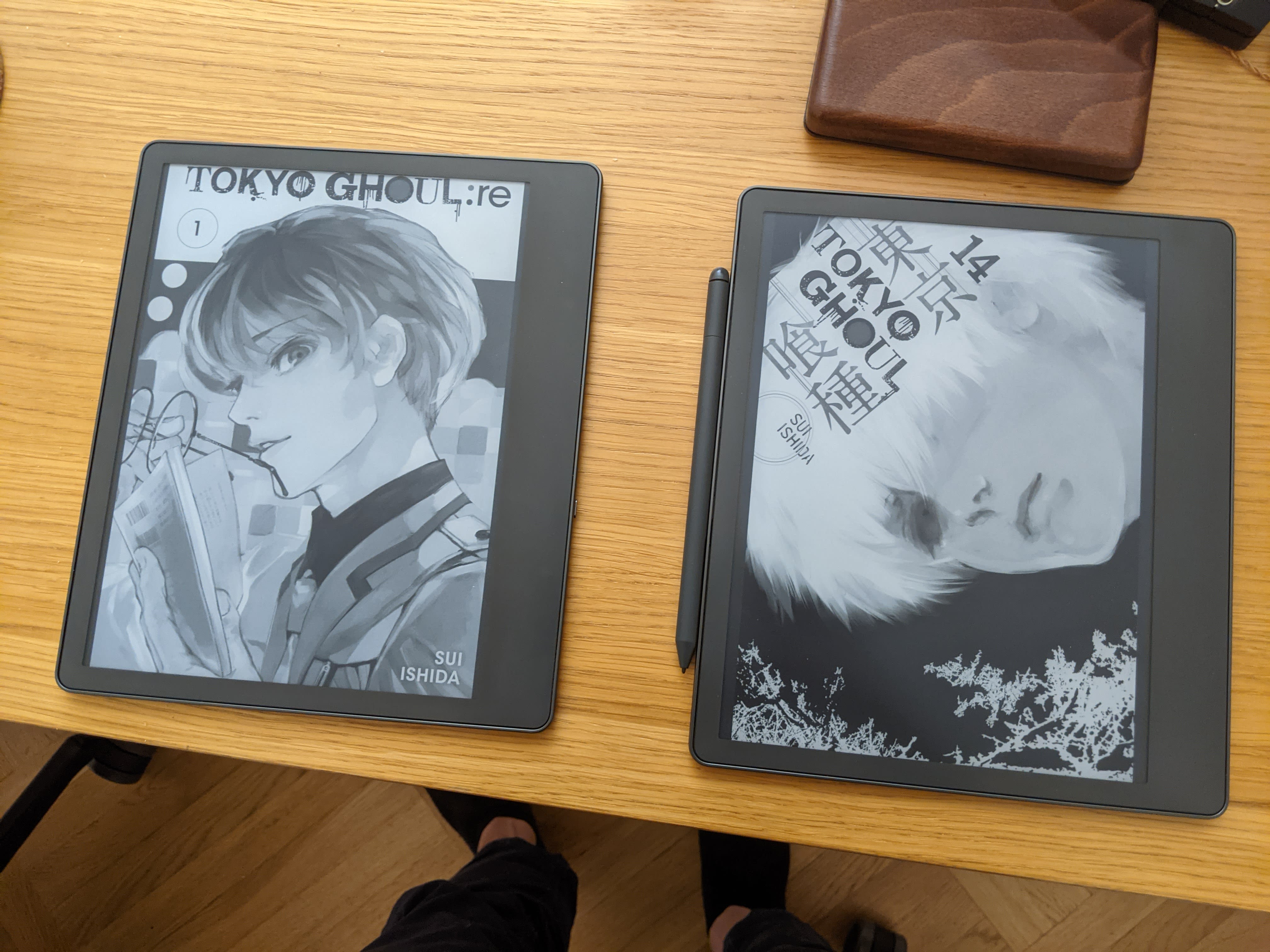

Dual Wielding Kindle Scribes

This is an informal post intended to describe a workflow / setup that I found very useful, so that others might consider adopting or experimenting with facets of it that they find useful.

In August 2023, I was a part of MATS 4.0 and had begun learning the skill of deconfusion, with an aim of disentangling my conflicting intuitions between my belief that shard theory seemed to be at least directionally pointing at some issues with the MIRI model of AGI takeoff and alignment difficulty, and my belief that Nate Soares was obviously correct that reflection will break Alex Turner’s diamond alignment scheme. A friend lent me his Kindle Scribe to try out as part of my workflow. I started using it for note-taking, and found it incredibly useful and bought it from him. A month later, I bought a second Kindle Scribe to add to my workflow.

It has been about six months since, and I’ve sold both my Kindle Scribes. Here’s why I found this workflow useful (and therefore why you might find it useful), and why I moved on from it.

The Display

The Kindle Scribe is a marvelous piece of hardware. With a 300 PPI e-ink 10.3 inch screen, reading books on it was a delight in comparison to any other device I’ve used to read content on. The stats I just mentioned matter:

300 PPI on a 10.3 inch display means the displayed text is incredibly crisp, almost indistinguishable from normal laptop and smartphone screens. This is not the case for most e-ink readers.

E-ink screens seem to reduce eye strain by a non-trivial amount. I’ve looked into some studies, but the sample sizes and effect sizes were not enough to make me unilaterally recommend people switch to e-ink screens for reading. However, it does seem like the biggest benefit of using e-ink screens seems to be that you aren’t staring into a display that is constantly shining light into your eyeballs, which is the equivalent of staring into a lightbulb. Anecdotally, it did seem like I was able to read and write for longer hours when I only used e-ink screens: I went from, about 8 to 10 hours a day (with some visceral eye fatigue symptoms like discomfort at the end of the day) to about 12 to 14 hours a day, without these symptoms, based on my informal tracking during September 2023.

10.3 inch screens (with a high PPI) just feel better to use in comparison to smaller (say, 6 to 7 inch screens) for reading. This seems to me to be due to a greater amount of text displayed on the screen at any given time, which seems to somehow limit the feeling of comprehensibility of the text. I assume this is somehow related to chunking of concepts in working memory, where if you have a part of a ‘chunk’ on one page, and another part on another page, you may have a subtle difficulty with comprehending what you are reading (if it is new to you), and the more the text you have in front of you, the more you can externalize the effort of comprehension. (I used a Kobo Libra 2 (7 inch e-ink screen) for a bit to compare how it felt to read on, to get this data.)

Also, you can write notes in the Kindle Scribe. This was a big deal for me, since before this, I used to write notes on my laptop, and my laptop was a multi-purpose device.

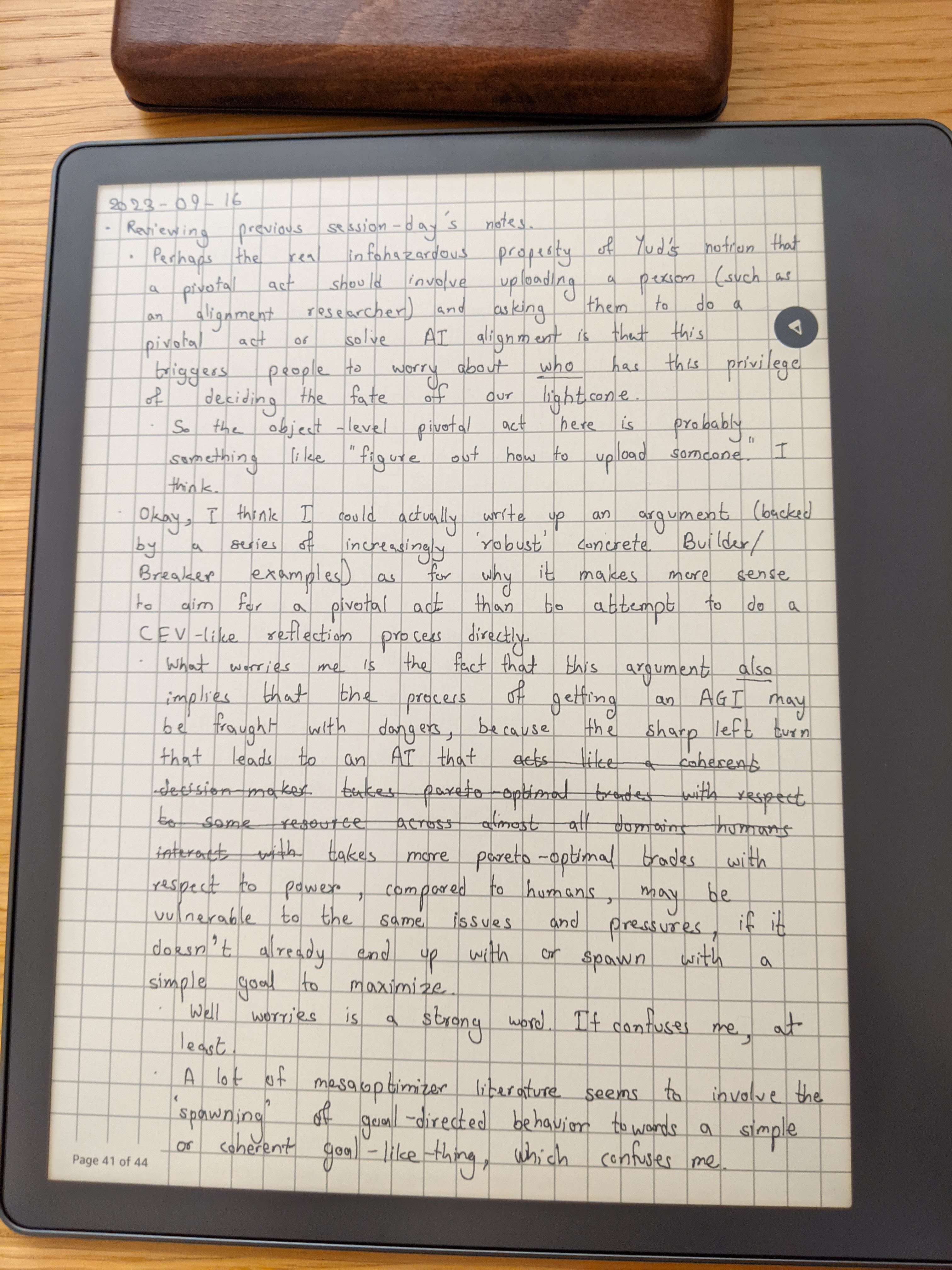

Sidenote: My current philosophy of note-taking is that I think ‘on paper’ using these notes, and don’t usually refer to it later on. The aim is to augment my working memory with an external tool, and the way I write notes usually reflects this—I either write down most of my relevant and conscious thoughts as I think them (organized as a sequence of trees, where each node is a string representing a ‘thought’), or I usually write ‘waypoints’ for my thoughts, where each waypoint is a marker for a conclusion of a sequence / tree of thoughts, or an interesting ‘thought’ that I want to think about more later. Outlining tools like Dynalist, Workflowy and org-mode (which is what I use right now) seem closest to describing how I feel I think and how I want my note-taking tool to look like, and this is also how I took notes on the Kindle Scribe.

Single-purpose devices enhance focus

The Kindle Scribe is a single-purpose device. You can read books on it, you can write notes on it. That’s it. The in-built web browser is an utter travesty and I hope you never have to use it.

And this is a good thing. The main benefit of a Kindle Scribe, to me, was that I couldn’t simply switch to another browser tab and do an internet search for something that just bubbled up in my mind that I was curious about, which would lead me to suddenly losing two hours to something that wasn’t actually relevant to what I wanted to learn. Now, if your day mainly consists of programming work, whether ML engineering or research, this workflow obviously doesn’t make sense for you. However, what I was doing was mainly thinking and writing thoughts, and reading alignment (and computer science and math and rationality) literature during that time period, so the workflow was almost perfect for me. I went from taking a week or two to read a book like Good and Real to a day or two.

Of course, a lot of important alignment literature is in the form of LessWrong or AlignmentForum posts, or posts on websites such as MIRI’s Blog. To get these on my Kindle, I used the WebToEpub Firefox extension, and archived many sequences and sets of essays as EPUBs that I would then upload to my Kindle and read on it. This way, the amount of time I spent using a device connected to the internet, like my laptop, was drastically limited, and I spent a lot more time working.

One to read, another to write on

One problem with the Kindle Scribe is that I couldn’t switch from the note-taking application to the book I was reading very quickly. It would take about 5 to 10 seconds in total to press all the menu buttons and wait for the device to react, to switch. This wasn’t practical given how I wanted to be able to write arbitrary numbers of pages of notes when a thought popped into my mind in reaction to, say, my realization that Gary Drescher’s description of reductionism seemed to elaborate on subtle mental motions that Eliezer hadn’t in his Reductionism 101 sequence, and my desire to think up what other mental motions might exist and try to write an informal “deconfusion algorithm”. You can only write a limited notecard-sized amount of notes attached to certain highlighted passages when inside a Kindle book—you need the note-taking app to write pages of notes.

So I bought another Kindle Scribe for 400 EUR. It was an expensive buy, but I was quite convinced that the money spent would be worth the productivity gain over the long term, and I felt like I was on an upswing in terms of financial and career stability. Additionally, if one of my Kindles broke or was stolen, I’d still have another at hand to continue referring to my notes and writing them and reading them, so I was essentially paying for resilience of my setup to a certain extent.

It worked pretty well. As of February 2023, I believe I’ve had about 400 pages worth of notes written in the Scribes, most of it related to alignment, rationality and computer science. The rest of it was related to my personal life. I would regularly the previous few days of my notes, either to find TODOs I had noted that I wanted to move to my task management system, or to re-orient myself for another day of research related to some specific topic.

I also sometimes used the two Kindle Scribes as two separate “notebooks” by keeping a “general” notebook open in one, and a “research” notebook open in another. I’d write down any personal life ideas and thoughts and TODOs in the “general” notebook, and thoughts related to deconfusion and alignment research and the specific topics I was reading about, in the “research” notebook. This removed another trivial inconvenience of not being able to immediately put thoughts onto paper whenever something interesting arose in my mind, and I believe I gained a lot from it.

Moving on

I began a sabbatical from alignment research in November 2023, mainly because I felt burnt out due to the pace at which I was working (which was, in hindsight, quite unsustainable). I stopped writing notes in the Kindle Scribes, but I continued to use them to read books and archived web essays. I learned to use (and set up) Emacs over the course of November and December, and found that I really liked taking notes and reading books in Emacs, so I gradually switched over to only using Emacs for note-taking and reading books.

Eventually I realized that while I really liked e-ink screens, I couldn’t stand using the Kindle interface for my books and notes. Ideally I’d be using an e-ink display as an external display, or an e-ink tablet running Emacs on a Linux/BSD operating system, but Kindle Scribes are very closed-down devices, and it was infeasible to consider trying to use its hardware to run the software I wanted to run on it.

I have recently begun experimenting with disabling internet on my laptop by default, which seems to have at least some of the effects that this workflow did. I’m still in the process of refining how I do things.

The one last clear use I had for the Kindles was to be able to read books when travelling—such as when at the airport or when in a plane. But when I actually did travel across continents recently, I found that I didn’t read any book (mainly because I didn’t feel like I had the cognitive fuel to read the stuff I wanted to read), and only used the Scribes to write my thoughts down—something I could do with a pen and paper too.

So I sold off my Kindle Scribes this week. I probably will eventually (when I feel like I have the slack to do so) test out an e-ink display connected to a laptop as a second screen. I hear that the framerate for e-ink screens is abyssmal, but I have hope that I could figure out a viable setup that uses e-ink displays eventually.

Ah, yes! With the reMarkable (another e-reader), I have a trick: I installed an app switcher so I could merely use a gesture to switch between a writing app and reading app.

I quite appreciated having a single slate to read and write on, in environments like the bus and the beach. Anyway, the software was somewhat buggy… and then I lost my stylus pen and then the replacement stylus pen. So now I just use a paper notepad, which I find works nicely.

I have a question. Would a paper notepad have worked for you instead of a second device? What’s better with the device?

Answered here, but TLDR is joy of using the Scribe, aversion to using notepads, and a worry of losing logs of what I wrote if written on paper.

I can understand that, since you keep the handwritings as they are.

Just sharing my own process, but I like the notepad because it’s ephemeral… I scribble what I learn, almost illegibly, and later type it up more nicely in my org-roam knowledge base, driven by sheer motivation to liberate myself from that stack of loose scribblings.

That way I get the upside of writing on paper (you learn better), but skip the downside that they’re hard to look up.

This is very interesting. I used to use org-roam and also experimented with other zettelkasten software over the past few years, but eventually it all grew very overwhelming because of the problem of updating notes. The bigger your note pile, the bigger the blocker (it seems to me at least) of updating your notes as you get a better understanding of reality.

Could you elaborate more on your setup, especially your knowledge base and how you use it?

Hmm. About 50% of my note pile can be browsed on https://edstrom.dev/. I have some notes on the method under https://edstrom.dev/zvjjm/slipbox-workflow.

How large did your note pile get before it felt overwhelming?

It’s true that sometimes I see things I wrote that are clearly outdated or mistaken, but that’s sort of fun because I see that I leveled up!

It’s also embarrassing to have published mistakes online, so I’ve learned to make fewer unqualified claims and instead just document the path by which I arrived to my current conclusion. Such documentations are essentially timeless, as johnswentworth explains at How To Write Quickly While Maintaining Epistemic Rigor.

Still, I’m keeping more and more notes private over time, because of my increasing quality standards. But ignoring the matter of private/public, then I don’t perceive updating as a problem yet, no. I don’t mind having very outdated notes lying around, especially if they’re private anyway. When I rediscover them, they will be effortless to update.

To your point about e-ink screens reducing eyestrain: white-on-black text may do the same thing. It’s reducing the light hitting your eyeballs by a factor of ten to a hundred. I’ve read books on a large phone screen in dark mode for a long time (since Kindle for smartphones has existed, I guess) and experienced zero perceptible eyestrain.

This has nothing to do with the distraction-reducing portion of your post, nor the handwriting notes portion.

There is much bikeshedding about eyestrain. I’ve seen convincing arguments, especially from older hackers, that a white background is actually less strainful for the eyes. I forgot what the arguments were—will write them down next time—but I don’t think it’s as simple as the amount of light hitting the eye. Currently I’d advise just trusting in personal experience.

And maybe experiment with increasing ambient light rather than reduce light from the screen.

Agreed that it’s not as simple as light hitting the eye. I’ve also tried to work on external monitors that are relatively far away for neutral focal distance. But I couldn’t find any good research or even theory on it.

FWIW, the majority of my book reading in white on black has been done in the dark in bed before sleeping, but at low contrast.

thanks for writing this! can you say a little bit more about the process of writing notes on a scribe? I’ve been interested in getting one, but my understanding is that e-ink displays are good for mostly static displays, and writing notes on it requires it to update in real-time and will drain the battery fairly quickly? my own e-reader is from like, 2018, so idk if there’s been significant updates. how often do you need to charge them when you’re using them?

The Kindle Scribe, IIRC has a 18 ms latency for rendering whatever you write on it using the Wacom-like pen. I believe that was the lowest latency you could get at the time (the Apple Pencil on iPads supposedly has a latency of 7-10 ms, but they use some sort of software to predict what you’ll do next, so that doesn’t count in my opinion).

I found the experience of writing notes on the Kindle Scribe great! It was about as effortless as writing on paper, with the advantage of being able to easily erase what I wrote with the flip of the Premium Pen. There are tail annoyances, but that didn’t seem to me to be worse than the tail annoyances of using physical pen and paper (whether gel ink, fountain pens, or ball point pens).

Writing on the Scribe does drain your battery faster. The number that comes to mind is that you can write on it continually for about eight hours before you wholly drain the battery, while if you only read on it, you don’t need to charge the Kindle for weeks.

I recommend the My Deep Guide Youtube channel for in-depth information about various e-readers and if you want to get up to speed on the current e-reader zeitgeist.

There are a number of other eink tablets on the market, most of which run Android and are therefore a good amount more customizable. For example, I’m using a Boox Note Air (https://shop.boox.com/collections/all/products/boox-note-air3), which has a similar screen and runs Android. It also comes with a split screen functionality, so you could connect a bluetooth keyboard, have the book open on one side and a vim emulator on the other. That’s pretty close to my workflow for reading books/papers.

I have the Boox Nova Air (7inch) for nearly 2 years now—a bit small for reading papers but great for books and blog posts. You can run google play apps, and even set up a google drive sync to automatically transfer pdfs/epubs onto it. At some point I might get the 10inch version (the Note Air).

Another useful feature is taking notes inside pdfs, by highlighting and then handwriting the note into the Gboard handwrite-to-text keyboard. Not as smooth as on an iPad, but pretty good way to annotate a paper.

The e-ink tablet market has really diversified recently. I’d recommend that anyone interested look around at the options. My impression is that the Kindle Scribe is one of the least good ones (which doesn’t mean it’s bad).

Can you say more about “couldn’t stand the kindle interface for books/notes?”. I’m trying to figure out if I should try this and don’t quite have a model of why it didn’t work for you (and whether that’d translate to me)

This is in comparison to using Emacs. When using Emacs as my interface for reading books and writing notes,

I can use a familiar UNIX file system to store my books as PDFs and EPUBs. I can easily back it up and interact with my collection using other tools I have (which is a real benefit of using a general purpose computing device). With the Kindle, creating and managing collections (an arbitrary category-based way of organizing your documents) is awkward enough (you need to select one book at a time and add it to a collection) given my experience with the last Kindle Scribe firmware that I just relied on the search bar to search for book titles.

When using Emacs, I can do a full text search of my notes file simply by pressing “s” (a keybind) and then typing a string. In contrast, while the notes written on the Scribe can be exported as PDFs, you don’t have the ability to search your notes. This wasn’t a dealbreaker for me, though, to be clear.

It is a bit hard to point at the things that make me want to use Emacs for it, because a load-bearing element is my desire to do everything in Emacs. Emacs has in-built documentation for its internals and almost every part of it is configurable—which means you can optimize your setup to be exactly as you like it. It feels like an extension of you, eventually.

This also somewhat drives my desire to use a simple and (eventually, given enough investment) understandable operating system that doesn’t shift beneath my feet. And given that both the interface and the operating system of the Kindle Scribe are opaque and (eventually) leaky abstractions, I feel less enthusiastic about investing my efforts into adapting myself to it.

oh, one question: if you mostly don’t look at your notes afterwards, why do you need a kindle scribe for them instead of a notebook?

data point: when I got my scribe, I was shocked at how good writing on it felt. It might or might not beat my favorite pen on the best possible paper, but it certainly beat anything less than that. I’ve tried the remarkable, and ipencil-on-ipad and didn’t have this experience. Maybe that’s because the scribe hasn’t seen much use and it will feel worse once it accumulates dirt, but I think Amazon did a really good job with the feel of it.

I also find there’s a difference emotionally between “this note is not optimized for reference and will be a pain in the ass to find later” vs “this note will disappear from history the moment you look away”. Knowing I could find something if I really really needed it frees up my brain from having to retain it.

Based on a focusing-style attempt at understanding why, it seems like there’s a certain sense of pleasure and delight associated with using the Kindle Scribe to write (and read) on, in my mind, and a sense of inelegance and awkwardness associated with writing on paper. Whatever experiences, beliefs, and sense of aesthetics underlies this is probably the driving factor.

I did have access to notebooks and pens and whiteboards when I bought the second Kindle Scribe, but hesitated to use any of them for writing down my thoughts. One thing that comes to mind when I imagine such alternatives is that I fear losing a log of what I thought and wrote, and I didn’t imagine doing so if I wrote it on the Scribe.