1. Intro

Over the last few years, I’ve taken three distinct “intro to philosophy” classes: one in high school, and then both “Intro to Philosophy” and “Intro to Ethics” in college. If the intentions vs consequences / Kant vs Mills / deontology vs utilitarianism debate was a horse, it would have been beaten dead long ago.

Basically every student who passes through a course that touches on ethics ends up writing a paper on it, and there is probably not a single original thought on the matter that hasn’t been said. Even still, the relationship between intentions and consequences in ethics seems woefully mistaught. Usually, it goes something something like this:

One school (usually a conflation of utilitarianism and consequentialism) says that an action is good insofar as it has good consequences.

Another school (associated with Kant and deontology) says that intentions matter. So, for example, it can matter whether you intend to kill someone or merely bring about his death as a result some other action.

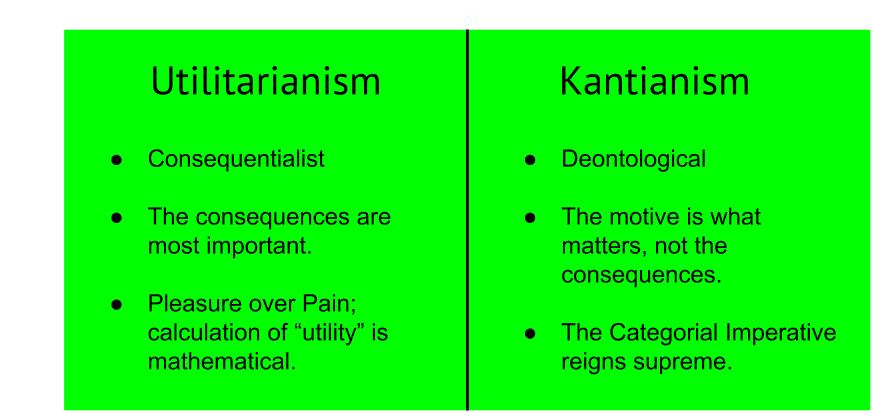

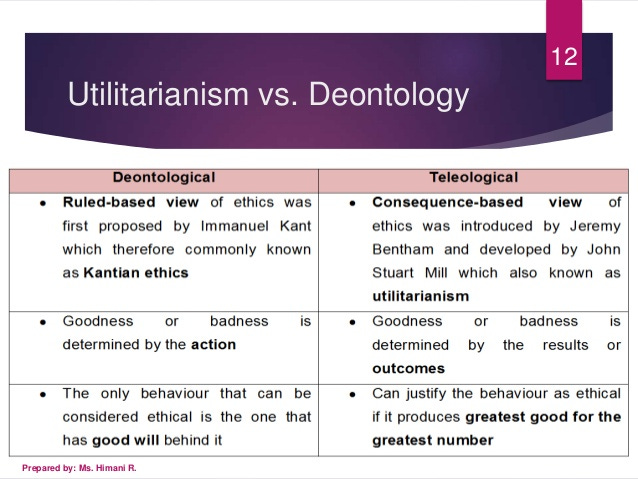

Want to see for yourself? Search for “utilitarianism vs deontology” or something similar in Google Images, and you’ll get things like this:

No, I didn’t make this. This is from the first page of the search results.

2. Intuitions

If you’re like me, both sides sort of seem obviously true, albeit in a very different sense:

The consequences are the only thing that really matter with respect to the action in question. Like, obviously.

The intentions are the only thing that really matter with respect to the person in question. Like, obviously.

Let me flesh that out a little. If you could magically choose the precise state of the world tomorrow, it seems pretty clear that you should choose the “best” possible world (though, of course, discerning the meaning of “best” might take a few millennia). In other words, consequentialism, though not necessarily net-happiness-maximizing utilitarianism, is trivially true in a world without uncertainty.

Now, come back to the real world. Suppose John sees a puppy suffering out in the cold and brings it into his home. However, a kid playing in the snow gets distracted by John and wanders into the road, only to be hit by a car. John didn’t see the kid, and had no plausible way of knowing that the consequences of his action would be net-negative.

Intuitively, it seems pretty obvious John did the right thing. Even the most ardent utilitarian philosopher would have a hard time getting upset with John for what he did. After all, humans have no direct control over anything but their intentions. Getting practical, it seems silly to reduce John’s access to money and power, let alone put him in jail.

Putting it together

Ultimately, it isn’t too hard to reconcile these intuitions; neither “intentions” nor “consequences” matter per se. Instead, what we should care about, for all intents and purposes, is the “expected consequences” of an action.

Basically, “expected consequences” removes the importances of both “what you really want in your heart of hearts” and the arbitrary luck associated with accidentally causing harm if your decision was good ex ante.

If you know damn well that not pulling the lever will cause five people to be killed instead of one, the expected consequences don’t care that you ‘didn’t mean to do any harm.’ Likewise, no one can blame you for pulling the lever and somehow initiating a butterfly-effect chain of events that ends in a catastrophic hurricane decimating New York City. In expectation, after all, your action was net-positive.

I highly doubt this is insightful or original. In fact, it’s such a simple translation of the concept of “expected value” in economics and statistics that a hundred PhDs much smarter than me have probably written papers on it. Even still, it’s remarkable that this ultrasimple compromise position seems to receive no attention in the standard ‘intro to ethics’ curriculum.

Maybe it’s not so simple…

Is it possible that philosophers just don’t know about the concept? Maybe it is so peculiar to math and econ that “expected value” hasn’t made its way into the philosophical mainstream. After learning about concept in a formal sense, in hindsight, it seems like a pretty simple and intuitive. I’m not sure I would have said the same a few years ago, though.

In fact, maybe the concept’s conspicuous absence can be explained by a combination of two, opposite forces:

Some professors/PhDs haven’t heard of the concept.

Those who have think it’s too simple and obvious to warrant discussion.

3. It Matters

To lay my cards on the table, I’m basically a utilitarian. I think we should maximize happiness and minimize suffering, and frankly am shocked that anyone takes Kant seriously.

What I fear happens, though, is that students come out of their intro class thinking that under utilitarianism, John was wrong or bad to try to save the puppy. From here, they apply completely valid reasoning to conclude that utilitarianism is wrong (or deontology is right). And, perhaps, some of these folks grow up to be bioethicists who advocate against COVID vaccine challenge trials, despite their enormous positive expected utility.

The fundamental mistake here is an excessively-narrow or hyper-theoretical understanding of utilitarianism or consequentialism. Add just a sprinkle more nuance to the mix, and it becomes clear that caring about both intentions and consequences is entirely coherent.

4. Doesn’t solve everything

Little in philosophy is simple. In fact, the whole field basically takes things you thought were simple and unwinds them until you feel like an imbecile for ever assuming you understood consciousness or free will.

“Expected consequences”, for example, leaves under-theorized when you should seek out new, relevant information to improve your forecast about some action’s consequences. However, we don’t need to resolve all its lingering ambiguities to make “expected consequences” a valid addition to the standard template of ethical systems.

Both, for different purposes. I haven’t really looked for papers or consensus, but I’m surprised not to hear more about the idea that ethics has multiple purposes, and it’s probably best to use different frameworks for these purposes. AKA “hypocrisy”—I decide consequentially, and judge others deontologically. Well, really, both are a hybrid (though often with different weights), because part of the consequences is how judgement changes future interactions.

There is a fundamental asymmetry between self and other. I simply can’t know other people’s actual motivation or reasoning. Sometimes they’re willing to claim a description of their thinking, but that’s not terribly trustworthy. This is related to having different reasons for moral evaluation of actions. I want to influence others’ future actions, and I want to understand things better for my future decisions.

Motivation (inferred or at least believably stated) is absolutely key in predicting other’s future behavior. Results are key in understanding whether my behavior had good consequences.

In truth, both are important, for both purposes. My own intentions are questionable, and do get examined and discussed with others—both to improve myself and to help others see how I prefer them to think. Consequences of others’ actions are important to audit/understand their intentions and future behaviors.

I can confirm that philosophers are familiar with the concept of expected value. One famous paper that deals with it is Frank Jackson’s “Decision-theoretic consequentialism and the nearest-and-dearest objection.” (Haven’t read it myself, though I skimmed it to make sure it says what I thought it said.) ETA: nowadays, as far as I can tell, the standard statement of consequentialism is as maximizing expected value.

There’s also a huge literature (which I’m not very familiar with) on the question of how to reconcile deontology and consequentialism. Search “consequentializing” if you’re interested—the big question is whether all deontological theories can be restated in purely consequentialist terms.

I think a far more plausible hypothesis is that we vastly oversimplify this stuff for our undergrads (in part because we hew to the history on these things, and some of these confusions were present in the historical statements of these views). The slides you cite are presumably from intro courses. And many medical students likely never get beyond a single medical ethics course, which probably performs all these oversimplifications in spades. (I am currently TAing for an engineering ethics course. We are covering utilitarianism this week, and we didn’t talk about expected value—though I don’t know off the top of my head if we cover it later.)

Source: PhD student in ethics.

Thanks for your insight. Yes, the “we simplify this for undergrads” thing seems most plausible to me. I guess my concern is that in this particular case, the simplification from “expected consequences matter” to “consequences matter” might be doing more harm than good.

This could well be true. It’s highly possible that we ought to be teaching this distinction, and teaching the expected-value version when we teach utilitarianism (and maybe some philosophy professors do, I don’t know).

Also, here’s a bit in the SEP on actual vs expected consequentialism: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/consequentialism/#WhiConActVsExpCon

Kant’s categorical imperative is weird, and seems distantly related to some of the reasoning you employ:

Overall I’d say...

Goals*, Knowledge → Intentions*/Plans → Actions

*I’m using “goals” here instead of the OP’s “intentions” to refer to the desire for puppies to not suffer prior to seeing the puppy suffering.

Why do consequences matter? Because our models don’t always work. What do we do about it? Fix our models, probably.

In this framework, consequences ‘should’ ‘backpropagate’ back into intentions or ethics. If it doesn’t, then maybe something isn’t working right.

How are “expected consequences” defined? According to whose knowledge?

a hypothetical omniscient observer, who perhaps couldn’t predict the butterfly effects because of quantum physics, but would have sufficient MacGyver skills to fix the trolley and save everyone?

“it is known”, defined by some reference group, for example an average person of the same age and education?

knowledge of the person who did the action?

Notice that the last option creates some perverse incentives. Do not learn too much about possible negative consequences of your actions, otherwise you will be morally required to abstain from all kinds of activities that your less curious friends will be morally allowed to do. Preferably, believe in cosmic karma that will ultimately balance everything, and that will make all your actions morally equivalent.

I was thinking the third bullet, though the question of perverse incentives needs fleshing out, which I briefly alluded to at the end of the post:

My best guess is that this isn’t actually an issue, because you have a moral duty to seek out that information, as you know a priori that seeking out such info is net-positive in itself.

You are treating ethics as an individual decision theory, as rationalists tend to. But ethics is also connected with social practices of reward and punishment. What is the point of such practices? To adjust people’s values or intentions. Intentions are the single most important thing for justice system.

Sometimes people have responsibilities, and can be charged for failing to execute them, say with ‘gross negligence’ as in ‘lack of slight diligence or care’.

>> Is it possible that philosophers just don’t know about the concept? Maybe it is so peculiar to math and econ that “expected value” hasn’t made its way into the philosophical mainstream.

I believe the concept of expected value is familiar to philosophers and is captured in the doctrine of rule utilitarianism: we should live by rules that can be expected to maximize happiness, not judge individual actions by whether they in fact maximize happiness. (Of course, there are many other ethical doctrines.)

Thus, it’s a morally good rule to live by that you should bring puppies in from the cold – while taking normal care not to cause traffic accidents and not to distract children playing near the road, and provided that you’re reasonably sure that the puppy hasn’t got rabies, etc. – the list of caveats is open-ended.

After writing the above I checked the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. There are a huge number of variants of consequentialism but here’s one relevant snippet:

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/consequentialism-rule/#FulVerParRulCon

Rule-consequentialist decision procedure: At least normally, agents should decide what to do by applying rules whose acceptance will produce the best consequences, rules such as “Don’t harm innocent others”, “Don’t steal or vandalize others’ property”, “Don’t break your promises”, “Don’t lie”, “Pay special attention to the needs of your family and friends”, “Do good for others generally”.

This is enough to show that expected value is familiar in ethics.

I don’t think rule utilitarianism, as generally understood, is the same as expected consequences. Perhaps in practice, their guidance generally coincides, but the former is fundamentally about social coordination to produce the best consequences and the latter is not. Hypothetically, you can imagine a situation in which someone is nearly certain that breaking one of these rules, just this once, would improve the world. Rule consequentialism says they should not break the rule, and expected consequences says they should.