Book Review: Open Borders

Edit: I now have a comment response post for this post on my personal website.

This is a (significantly updated) cross-post from my personal website. All sources are from the book unless otherwise mentioned.

Bryan Caplan is an economist at George Mason University known for his wacky libertarian views about various social and political issues (especially education). Open Borders: The Science and Ethics of Immigration is his latest book, which is in the format of a graphic novel illustrated by Zach Weinersmith of SMBC fame. The graphic novel format works really well. The art style is cute and non-fiction graphic novels are grossly underrated (some favourites of mine are Maus and Logicomix). Realistically, most people are not going to read a regular book about the economics of immigration. But this way Caplan can lure us in with fun cartoons!

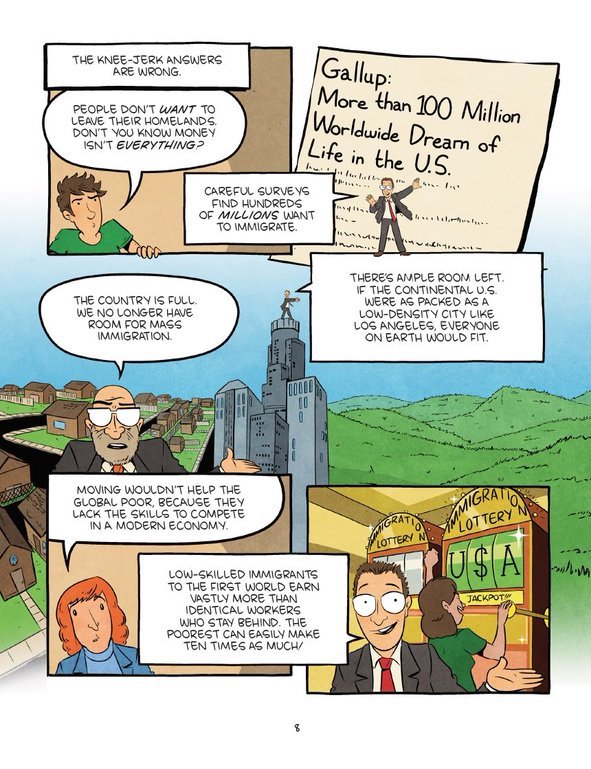

Caplan really does believe that there should be no restrictions on immigration whatsoever, and that’s exactly what his cartoon representation argues for in this book. The basic argument goes like this: people should, in general, be allowed to make decisions that they think will improve their lives, assuming they’re not hurting anyone. Moving to a new country is exactly such a decision. Since immigrants often move in search of work, moving is associated with a massive increase in economic prosperity. By moving to the US and receiving no additional training or education, the average citizen of a developing country can expect their income to increase fivefold; and for countries like Nigeria, tenfold. This is because developed countries are safer and have better quality institutions, so immigrants are more productive in them. Also, the opportunity cost of workers in rich countries is higher, hence why service workers like gardeners are so much more productive there. The gains are so vast that a standard estimate is that open borders would double world GDP. Yet rich countries continue to restrict immigration, sometimes through formal caps, and sometimes through complicated bureaucracy and paperwork which at best dissuades people from entering and at worst makes it literally impossible (like rejecting you for not filling out the middle name section on a form when you don’t have a middle name). Some of the arguments against immigration are xenophobic or racist, but many are legitimate concerns brought up in good faith. Most of them are not borne out by careful consideration of the evidence. The consensus among economists is that immigration does not generally decrease natives’ wages. Nor does it lead to an increase in poverty, crime, or a significant strain on the welfare state and social services. While the data about this are more unclear, immigrants are barely different from natives in their political views, and they adopt a lot of the cultural values of their destination country. Hence, the book argues, the contrary considerations are not enough to overwhelm our initial presumption in favour of allowing people to move, and so we should have open borders.

🎵 I want to be in America, I want to be in America 🎵

Open Borders is an extremely US-centric book. As someone from the mystical land of not-America, this is something that frustrates me about a lot of nonfiction. Caplan justifies his focus on the US by saying that his audience is mostly American and that that’s where the highest quality data exists. But in this case, the book makes a way narrower argument than it sets out to. By focusing primarily on America, the case is made stronger than it otherwise would be. Immigrants commit more crimes than native-born Europeans but fewer crimes than native-born Americans. Immigrants to the US assimilate unusually well. In a shocking turn for the Cato Institute, one of their researchers says that this is just because European countries have more highly regulated labour markets.

Focusing so much on the US is bizarre because the European Union has open borders between its member states! Surely analysing whether this has gone well is the single most convincing piece of evidence about open borders. Ireland is 17% foreign-born, a significantly higher proportion than the US, and from eyeballing the data it looks like the immigration rate to Ireland has nearly quadrupled in the last 20 years. Meanwhile, it’s doing pretty well and looks to be on track to become one of the richest places in the world. This would seem like a major success story of immigration. Yet Caplan only talks about the EU for a few panels toward the end of the book. This level of parochialism isn’t justified.

Until the 1920s, the US had de facto open borders, and this is another thing that I wish Caplan had dug into more. Did this work? How did infrastructure cope? What was the wage premium of immigrating?

Open borders would be the largest social transformation ever, and there isn’t even very much research about it. We should be extremely humble about our views on complex topics, and the downsides of open borders, if we are wrong, are quite significant. Caplan is unusually scrupulous about making sure his claims are backed up by the data. His book The Case Against Education is one of the most meticulously researched books I have read. So, it was a bit disappointing that there weren’t more margins of error attached to his claims. How confident are we that open borders would really double world GDP? 10%? 50%? 90%? After reading about the replication problems in economics and the colourful uses of statistics to get one’s desired conclusion, I don’t find these kinds of projections very convincing. More convincing would be natural experiments and case studies, although I mentioned that the EU—the most compelling such example—is not talked about much.

Inertia is the most powerful force in the universe

Gallup finds more than 100 million people want to migrate to the US. 750 million say that they would leave their home country if they could. But we have reason to doubt that people would actually act on this. This makes open borders more palatable to those that are sceptical of immigration; it wouldn’t be as different to the status quo as you might expect. During the Greek financial crisis, only 3% of the Greek population left, at a time when the unemployment rate was 27% – and Greeks have more than a dozen prosperous destination countries to choose from with no paperwork involved! Inertia truly is the most powerful force in the universe. Caplan’s defence of his high estimates of the number of future immigrants is that, once the ball gets rolling, more and more people from a particular country will move. Historically, immigration from Puerto Rico to the US was lower than you would expect given the difference in economic opportunity, but then Puerto Rican communities formed in many US cities, and more and more people moved. So insofar as truly huge numbers of people would immigrate, they would probably do it over a long period of time.

A corollary of migration being good for the economy is that big countries should do better, because they don’t have internal barriers to movement. How much of India and China’s economic growth is a result of the fact that they’re really big? When Caplan pointed this out, I was pretty surprised I hadn’t thought about it before. This is discussed in one panel on one page, but I would like to see the argument developed more. Do more populous countries have greater growth in the long run? If so, this points us in the direction of open borders. I liked how Caplan talked about what Lant Pritchett calls ‘zombie economies’ – economies kept alive by restrictions that forbid people from leaving. A large fraction of the US has been declining in population for decades, yet we would regard it as absurd to say that people shouldn’t be allowed to leave Nebraska because doing so would go against Nebraska’s interests.

The argument from “more people are better”

In One Billion Americans, Matt Yglesias argues for large-scale population growth, partially through immigration but mostly through an increase in fertility, to maintain American pre-eminence over China and India. For all its failings, American dominance is better than the alternative. And America is at a disadvantage on this front by having a billion fewer people than the Asian giants. I’m not sure whether this argument should have been in Open Borders: it would take a long time to justify, and open borders appeal to left-libertarian sensibilities that might be offended at the idea of American global hegemony. But it would be an interesting project for the open borders community to look at. How important are marginal increases in population for geopolitical power? Are spurts in population growth followed by increases in various measures of hard or soft power?

In the US, a disproportionate amount of innovation comes from immigrants. More inventors immigrated to the US from 2000 to 2010 than to all other countries combined. Immigrants account for a quarter of total US invention and entrepreneurship. Maybe this is just because America selectively lets smart and innovative people move there. But maybe there are some agglomeration effects going on here specifically related to immigration? Immigration and clustering people together seems to have been key to the success of various intellectual hubs throughout history, like the Bay Area recently, Vienna in the 20th century, and Edinburgh in the 18th century. This is a ripe topic for progress studies to tackle. Aesthetically, I agree with Caplan’s choice not to talk about this much. People talking about all the “amazing contributions” made by a certain immigrant group often comes off as condescending, in much the same way as token engagement with other cultures might. Make the case for immigration from prosperity and freedom, or don’t make it at all!

There are various arguments related to longtermism that Caplan didn’t use. The downsides of immigration (higher crime, perhaps draining the government’s budget) are temporary but the upsides (higher economic growth) bear their fruit over centuries and will likely affect billions of future people. If you buy the argument that what matters most morally is our consequences on the long-run future, this is a point in favour of open borders.

Greying is not something that Caplan discusses much. This might surprise you: a common-sense case for immigration is that people in Europe and America are getting too old to work and they need immigrants to replenish the workforce. There aren’t really jobs that “Americans won’t do”, since, if people don’t like doing something, the wages will rise until they start doing it to meet demand. However, this price is such that there’s significant deadweight loss – mutually beneficial trades that can’t occur. For instance, more people would get more childcare if the government allowed more immigration. Caplan discusses this, but I didn’t feel sufficiently inspired about how great this would be. If I lived in a place with open borders, I’d probably have a personal assistant!

Inequality and selection bias

Caplan is an economist, so I can’t really argue with his reasoning about the economics of immigration. While the book is pretty convincing in arguing that immigration is the best tool we have for reducing poverty in an absolute sense, I’m less clear about the effects on poverty in a relative sense. Poor Americans still have it great by global standards, but they certainly don’t feel that way, and the point of all this prosperity is presumably to make people subjectively better off.

Currently, the people who move from poor countries to rich countries are self-selected for being intelligent and conscientious. But what happens when unmotivated unskilled people start coming too? Under the current regime, these people would be relegated to the fringes of society. Does this mean open borders could even make some immigrants worse off, even if their paycheque triples? Checking the strength of the selection bias doesn’t even seem that hard: compare people who were let in randomly or through a competitive process in otherwise similar immigration programs. I’m sure there are papers that look at this that I’m unaware of.

This is related to the concern over brain drain, which has been massively overblown. Developing countries are not even close to coming up against the ceiling of people who are capable of being in-demand professionals like doctors. Crudely, the reason why there aren’t many engineers in Chad isn’t that Chad trained a bunch of engineers who all left; it’s that Chad doesn’t have many engineers full stop. A lot of the philosophical literature on open borders is confused about this point. Doctors immigrating from developing countries doesn’t reduce the supply of doctors in those countries. The Philippines’ supply of nurses has actually increased as a result of the fact that they send so many nurses abroad. Think about it: if you knew that your only option was to work in a dysfunctional public health system in your home country, would you train to be a doctor?

Caplan also doesn’t consider the extent to which racism and xenophobia might flare up in response to immigration (though he does have a great section covering the effects on social trust). The countries that are the closest to having open borders are the Gulf states; they have many migrant workers from countries like Bangladesh and Sri Lanka. On one level, this is great: Qatar benefits from cheap infrastructure, the Sri Lankans benefit by getting higher-paid jobs. But I do also fear that this will lead to a racially segregated dystopia.

Immigrant groups might become stratified based on how wealthy they were to begin with. African immigrants would be deeply poor, followed by not-as-poor Indians, then richer Chinese, and so on. What happens to the politics and culture of a society that is so racially stratified? This is of course also a problem now, but I wonder what it would mean to scale it up so much. Statistical discrimination would be rampant, at the very least.

I initially was very sympathetic to the view – defended by some philosophers – that wealth inequality is not a problem per se; poverty is. But the more I think about it, the more this feels like squabbles over semantics. Yes, the distribution of resources is not intrinsically morally significant, but the mere fact that poor people don’t have much money isn’t intrinsically morally significant either. Take the literature with a grain of salt, but, holding poverty constant, inequality seems to have lots of negative effects on all sorts of outcomes, including crime. Given that it has negative outcomes, and is frequently caused by unjust social conditions, inequality – which would be increased within countries by open borders – is worth worrying about!

One of the more sophisticated arguments against redistribution is that excessive transfer payments aren’t compatible with high levels of immigration unless you want to go bankrupt, and immigration is better at reducing poverty than government programs. But is this really true? Do places that grow their welfare state subsequently shrink their level of immigration, or shift it toward higher-skilled immigrants? If so, it’s certainly odd that support for immigration and welfare are moderately correlated beliefs.

The political views of immigrants

Caplan has a section where he addresses the political effects of immigration, largely drawing on data from Alex Nowrasteh at the Cato Institute. He finds that immigrants are a tiny bit more left-wing than the general population but that their kids and grandkids regress to the political mainstream. This is again a case in which immigrants assimilate more poorly in Europe; it takes more generations for them to be politically indistinguishable from natives. Immigrants and natives didn’t have a partisan difference until the 1980s, and the partisan difference comes from immigrants being more likely to identify as independent, not from being more likely to identify as Democrat. This is interesting but doesn’t address the tail risk of immigration leading to a dysfunctional level of polarisation or backlash. It’s probably the case that the biggest harms from immigration come from people irrationally panicking about immigration, but (surprise!) people are in fact irrational.

Here’s Michael Huemer, in one of the most well-known philosophical defences of open borders, on the effects of immigration on culture:

Empirically, it is doubtful whether apprehensions about the demise of American culture are warranted. Around the world, American culture, and Western culture more generally, have shown a robustness that prompts more concern about the ability of other cultures to survive influence from the West than vice versa. For example, Coca-Cola now sells its products in over 200 countries around the world, with the average human being on Earth drinking 4.8 gallons of Coke per year. McDonald’s operates more than 32,000 restaurants in over 100 countries.

This sidesteps the objection. Mass migration to the US is not a concern because Coca-Cola will go out of business; it’s a concern because democracy, freedom of speech, and the rights of women and LGBT people are deeply unpopular in much of the world. Importing millions of people from autocracies and societies that are otherwise deeply illiberal may well have adverse effects on democracy. This makes a good case for having long waiting times for citizenship and voting rights.

What about the environment?

At no point does Caplan address the environmental harms of open borders. Moving people from low-emitting poor countries to high-emitting rich countries would lead to a pretty dramatic acceleration in global carbon emissions. Admittedly, keeping most of the world poor is a terrible climate change strategy, but there are some climate problems you might want to solve first before advocating for open borders. I’m confident that Caplan has reflected and come to the conclusion that there are no climate problems that we can solve in a short enough time to justify the harm caused by delaying open borders, but he doesn’t show his work. Sometimes, climate change gets used as an excuse for opposing almost any societal progress. This is unfortunate. But “Open borders would create a gigantic problem, namely massively accelerated climate change, but the benefits outweigh the harms” was not the argument I took away from the book. “Open borders are so good, and the objections are not that significant” was the argument I took away from the book.

There are considerations that dampen the environmental objection. Immigration would probably accelerate the trend of urbanisation, and cities are better for the environment (smaller houses, more use of public transport, etc.). A world with open borders would be much richer, and so would have a lot more money to throw at the problem of climate change. People would also be able to move away from the regions that are worst affected. And emissions per capita are going down in most rich countries, while they’re going up in poor ones.

I’m also concerned about the animal suffering that would result from open borders. Globally, the production of meat, 90% of which comes from factory farms, creates an almost unimaginable level of suffering. There are two reasons why open borders would make this worse: the Western diet is more meat-heavy than diets from other rich parts of the world, and richer people, in general, consume more animal protein. People sometimes talk about the meat-eater problem: many interventions in global development look much less cost-effective if you give moral concern to animals, since, if the interventions save human lives or make people better off, they lead to greater meat consumption. Increased demand for meat may be unusually harmful now, because it further entrenches factory farming as the default way meat is produced.

Shifting the Overton window

Toward the end of the book, Caplan discusses whether it’s a good idea to be advocating for open borders, or whether the idea is so radical that it will turn people off immigration even more. He comes to the conclusion that discussing open borders shifts the Overton window toward increasing immigration. I’m not so sure.

Dominic Cummings has argued that Brexit neutralised immigration as an issue in UK politics because it isn’t so much immigrants that people object to, but the feeling of lack of control. Indeed, immigration to the UK hasn’t radically changed post-Brexit. Some people just feel the government is unrepresentative and dismissive of their concerns about immigration. It’s not like most people even have any idea how common immigration is, nor do they appear to care. Logical debate has not been tried and found wanting. It has been found difficult and left untried.

This book made me think about what low-hanging fruit might exist in the space of increasing immigration. As mentioned, immigration to many countries is not formally capped but is de facto limited by being confusing and costly. Have people tried to start companies to fill this niche of streamlining immigration? Are there any foundations willing to run this kind of thing as a non-profit? Google turns up surprisingly few results. This is a promising area for effective altruists to look into.

Thanks to Fergus McCullough, Gytis Daujotas, and Sydney for reviewing drafts of this post.

Without commenting on the rest of your post, I am extremely suspicious of your climate change argument.

When the 2008 crisis led to an extended recession, I do not recall many people saying ‘actually this is good, as reduced economic activity due to recession will improve the climate’. When Haiti got hit by natural disasters, lots of people died, and society and the economy collapsed, I again recall very few people saying this.

If you are a single-issue climate change voter, and genuinely do consider everything via a lens of ‘good things are actually bad because they will hurt the environment, and bad things are actually good because they will help the environment’, I withdraw this criticism.

But if your first thought when you read a newspaper report about falling murder rates is not ‘oh no, all those people continuing to live First World lives, think of the environment’, it seems disingenuous to expect Caplan to do the same.

One weirdly striking thing missing from Caplan’s book and this review is one of the most common objections people have to mass immigration: loss of their dominant culture.

Given how much anti-immigration rhetoric focuses on precisely this argument, it is bizarre for Caplan not to take it seriously and makes me concerned he is living in an academic bubble so heavily biased towards pro-immigration arguments that he’s failed to even acknowledge it as a concern.

Consider that many people in the UK/Europe bemoan that their major cities have entire sections with no native speakers, are full of Arabic/Polish/Chinese signage or whatever, and bear no resemblance to the place they grew up in.

Lots of anti-immigrant US groups online also fear the the displacement of Christianity (or Judeo-Christian culture) as the major value system in America. A less controversial version of this argument may just be that people value shared continuity/history with their fellow countrymen and enjoy having a sense of kinship with people who share their cultural background.

I’m not saying this the best argument, nor am I agreeing with it, but it is extremely common.

We can hand-wave this away, or say it isn’t important, but it is a problem that people viscerally feel and if you’re going to argue for something as radical as open borders you better have a good argument for why those people should ignore the feeling that their own cities don’t feel like their own country the more mass-migration occurs.

It may be simply that the pro-immigration arguments outweigh this concern, but again, Caplan needs to convince Middle America of that and at least take it seriously.

Until you do, the economic case will never persuade anyone.

“We should be extremely humble about our views on complex topics, and the downsides of open borders, if we are wrong, are quite significant”

But this argument cuts both ways. The downsides of closed borders are also quite significant. However, the intervention is closed borders, not open borders; the evidence is on the side of open borders, not closed borders; the vast majority of worl’s movements are not across borders, so free movement is the rule and restricted movement the exception. Why would a “precautionary principle” favor the case for closed borders?

I don’t think your claim that ‘the intervention is closed borders’ is quite right. The status quo is differing levels of restriction of movement between regions and nations that have developed as a result of long historical processes. As the EU demonstrates, it can be as difficult to manage (relatively) open borders as it is to manage (relatively) closed borders. The status quo is that countries and regions choose different levels of migration, and different kinds of migration, to suit their values and needs, therefore the UK, the EU, the US, Canada, China, the Gulf Countries and Australia have all developed hugely different migration policies, while all remaining largely successful as nations over the last few decades.

Arguing for ’100% closed vs. 100% open borders’ gets very abstract and it’s difficult to argue from the facts rather than ideology, because fully open or closed borders are so rare. Although it can be useful to try and nudge the Overton window, the intervention is always going to be a marginal shift in the status quo, but even then, we should be humble about the downsides of marginal shifts either way.

What I meant by “the intervention is closed borders” is that closed borders require action by the state, open borders are the “do nothing” stance. This seems pretty clearly true to me.

I think you are arguing against my point that open borders are the rule and closed borders the exception. It’s true, most countries adopt some form of restriction of movement. But that does not negate the fact that most movement people make (between cities, regions, etc) is not restricted. And as is mentioned in the post, they were not restricted historically either.

Yet one could still argue that “the rule” is this very specific combination which we find in countries today of practically unlimited movement within borders and difficult movement across borders, and then invoke a precautionary principle. But that sort of thinking would imply a rejection of basically any proposed change to the status quo. I don’t think anyone would propose consistently following such a conservative framework for policy implementation and if they did—ironically—I think the result would be a level of policy paralysis which would be disastrous.

Do you favor any policy changes? If you do, can you affirm that it 1) has more evidence in favor of it than migration; and 2) could not conceivably have disastrous results?

I’d say that, in reality, open borders do require action by the state; just like deregulation, it’s something that is often portrayed as ‘inaction’, but actually ends up quite complex in practice. The EU/ Schengen zone, for example, needs to harmonise residency policies and external borders, develop cross-border policing and justice coordination between nations, harmonise workers’ rights and healthcare, all without a common language or a common defence force. Especially as most laws are designed for a world with borders, you would need to change a lot to implement open borders. Of course, you could just completely scrap the border police, visas, and any border checks and see what happens, but I doubt that anyone is seriously suggesting that.

I’m not arguing that we should always invoke a strict precautionary principle based on the status quo, although a mild ‘Chesterton’s Fence’ precautionary principle until we understand the facts on the ground is always prudent. Either way, any change we want to make or campaign for will be marginal, based on a country’s specific circumstances (imagine Canada vs. Israel). I presume you agree that it’s a bit ridiculous to have a hard border between the US and Canada, but I presume you wouldn’t recommend that Israel opens her gates freely to the Arab world.

As for the ‘policy paralysis’ idea, any policy I would suggest or campaign for would be at a far, far smaller scale than open borders. This is both for practical reasons, and out of a precautionary principle. I think it would probably be more ethical if the UK spent 2+% of its budget on foreign aid, for example, but I think that’s both politically impossible and could possibly have adverse consequences (if we cut other parts of the budget), but I’ve contributed to an (unsuccessful) campaign to keep the aid budget from going down from 0.7%, which I’m very confident is the ethically superior choice, and whose adverse consequences would be much smaller.

With migration, we all have a basic understanding of how migration can work and how it can cause harm, therefore any intervention I’d propose would try to harness these benefits and mitigate the harm based on this model. I might dedicate some time or effort to loosening restrictions concerning a certain population (I would be in favour of post-Brexit free movement to the UK by Aussies and Kiwis, for example), but I might also support restricting certain kinds of migration. I’ve read Caplan’s book and a lot of migration literature, and while I’m generally pro- migration at the margins, I don’t think we have anything like good evidence that open borders work, largely because all the evidence is theoretical and/ or based on controlled migration (or migration within a group of similar income countries etc.).

Are you implying that the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 had no teeth and was mostly symbolic?

The US is famous for being culturally and politically polarized. What does it even mean for immigrants to be “barely different from natives” politically? Do they have the same (polarized) spread of positions? Do they all fit into one of the existing political camps without creating a new one? Do they all fit into the in-group camp for Caplan’s target audience?

And again:

If the US electorate is polarized left-right, does being a bit more left-wing mean a slightly higher percentage of immigrants than of natives are left-wing, but immigrants are still as polarized as the natives?

Finding the percentage of “immigrants” is misleading, since it’s immigrants from Mexico and Central America who are politically controversial, not generic “immigrants” averaged over all sources.

Statistics show that Latinos vote around 2⁄3 for the Democrats. That’s a pretty big imbalance. And it’s even more imbalanced than those statistics show because Cubans are likely to vote Republican, and the immigrants who are the center of current political controversy don’t include Cubans.

I’m no expert on American immigration issues, but I presume this is because most immigrants come in through the (huge) south land border, and are much harder for the government to control than those coming in by air or sea.

However, I expect immigrants from any other country outside the Americas would be just as politically controversial if large numbers of them started arriving, and an open borders policy with Europe or Asia or Africa would be just as unacceptable to most Americans.

Are Americans much more accepting of immigrants from outside Central and South America?

The question is whether immigrants have different political positions than natives.

Latinos (and especially non-Cuban Latinos) absolutely have different political positions than average natives, and immigration consisting largely of them would in fact have the effect that Caplan denies.

I expect that if lots of them (or their descendants) voted for Republicans, they wouldn’t be politically controversial, because the Democrats and the left are spearheading the push for more immigration, and they would abruptly stop doing so. (This would not be compensated by Republicans pushing for them, because Republicans have no power to make such a push.)

You can if the other 20 million pay more in taxes than the 30 million use on net—especially if the whole 50 million then have citizen kids that are net fiscally positive (and who would presumably not be counted as “non-citizen households” in these statistics). The balance here is a quantitative problem that Caplan and Weinersmith try to estimate in their book.

“Have people tried to start companies to fill this niche of streamlining immigration?”

Lots! I live in China, and immigration/visa support is a big industry. If you want to send your kid to a British university, you go to a consultant, who work very much like travel agencies. They offer you an attractive range of options to suit your budget and test scores, help you fill out the forms, send you to take whatever additional tests are necessary (even offer a little help with the tests if you can’t quite pass them yourself, wink wink), and can provide airport meet’n’greet and homestay accommodation in country.

At the rougher end of the industry, this is what people smuggling/trafficking is.

Great review, I agree very strongly with the America-centric nature of the book being annoying and misleading, but I have a few niggling points:

“Do more populous countries have greater growth in the long run? If so, this points us in the direction of open borders.” I think this is true, that populous countries have greater growth on the whole. But this doesn’t seem to point to open borders. I think there is a selection effect whereby only countries with a particularly strong system of governance don’t split up into other countries, and it’s the strong governance that creates growth. And some large nations don’t even have open borders between regions; it’s actually easier to move from rural Poland to Paris for work, and benefit from public services there, than it is to move from rural Hunan to Shanghai.

“There are various arguments related to longtermism that Caplan didn’t use. The downsides of immigration (higher crime, perhaps draining the government’s budget) are temporary but the upsides (higher economic growth) bear their fruit over centuries and will likely affect billions of future people.” I disagree with this, connected to reasons you mention later. The downsides can continue, even accelerate, for a good few generations, and then become fundamentally unpredictable; in France, for example, children of immigrants are more likely to commit crimes and be unemployed than 1st gen immigrants. Muslim migrants are less likely to want to assimilate to European countries than they used to be; a 2nd gen Muslim woman in Bradford is far more likely now to wear a Burqa than a 1st gen woman was 20 or 30 years ago, for example. For most people concerned about immigration, it’s the fact that their country (imagine Ukraine/ England/ Tibet/ Israel/ Luxembourg) won’t be their country anymore in a few decades (or centuries) that worries them. Tibetans have seen the number of Han Chinese in their nation rapidly increasing over the past 50 years, and they reasonably fear that once Tibet is 60-70% Han, they’ll either have to assimilate or be reduced to something akin to Aboriginals on reservations. Similarly, the theme of Soumission by Houellebecq is arguing something similar for France; if the rate of Islamic immigration continues to increase, then it’s possible that within a few decades an Islamist candidate could start implementing Islamic law within a European country (as we see regionally already, with divorce courts). You can only imagine if Israel were to allow open borders with her neighbours… This is to say that negative impacts of open borders may not be temporary, and could affect the mid-to-long-term identity, culture, norms and stability of a nation. It’s hard to make concrete predictions, but I’m tempted to predict that low-immigration, high-GDP countries (or countries with very selective migration, like Switzerland) will be more politically stable in the coming few decades. Paul Collier explains this dilemma well in his book, Exodus.

“The countries that are the closest to having open borders are the Gulf states; they have many migrant workers from countries like Bangladesh and Sri Lanka.” This seems the strangest line of the review. Depending on your definition, I’d say that the Gulf States have the opposite of open borders. They previously had targeted immigration policies allowing other Arabs from the MENA region to work there, then they caused too many social problems, so the Gulf countries threw them all out, and invited targeted immigration from a few specific poor countries (with people who didn’t speak Arabic, and therefore wouldn’t get involved in local politics). There is actually a decent amount of social mobility in these countries (a strangely high proportion of my friends are Gulf-state Indians based in Europe), so I wouldn’t be too worried about long-term racial segregation. If you see this story of poor South Asians taken out of poverty by working in the gulf, the Gulf States are a strong argument for a very ‘non-open borders’ way of doing mass immigration: inviting large numbers of migrants to come to a country on guest worker schemes, with very limited rights. Although these migrants have no social support, and can be thrown out on the whim of the recipient country, they can make loads of money compared to back home. I actually think this might be a really good idea, and this is also similar to what Chinese cities do with domestic migration, which avoids parts of Beijing and Shanghai turning into huge shantytowns. However, as you mention, having a ‘second-class’ population sits poorly with European norms and sensibilities.

Thank you for making a great point! Large countries do implement limits on internal migration to ensure political stability. The Chinese system is called hukou if anyone wants to read up on it; I am no expert myself. I would, however, disagree that these limitations suggest there is no free movement. In fact, the very existence of these limitations suggests we should open up compared to the baselines, but perhaps not fully.

The population of Shanghai grew almost 100% from 14M to 27M within the last 20 years—and the city transformed into a wealthy metropolis like NYC. According to Wikipedia, consistent with my intuition, a relaxation of Hukou migration restrictions coincided with the (post-)Deng Xiaoping era of stability and prosperity. So internal migration in China is enormous and while it is hard, it can’t be that hard to move. Now, of course, these people are mostly Han Chinese and it is an interesting question how many immigrants of a different cultural background we could handle in Europe.

Agree, it is naive to argue for a “free lunch”. As far as I recall, there is good economic evidence that migration from e.g. Afghanistan is a net cost for the taxpayer in Germany despite the younger age structure of the immigrants. (It only works out under extremely optimistic assumptions, if the immigrants can find higher-paying jobs than expected.) Migration (from [very] poor countries) should be considered a form of “foreign aid”, it is a cost; and it is a question of political stability. Having many immigrants is useless if the AfD or Front National then rises to power, reverts your measures and sabotages democracy.

How does political stability change, though, is it linear with the number and type of immigrants or are there thresholds?

Does this point argue strongly against open borders? Both systems could work fine and strike a similar balance. Higher migration, lower migrant rights. Lower migration (but still higher than the status quo), better migrant rights. Either way, we are trying to maximize the same product: [Number of immigrants] x [net improvement in migrant life = wellbeing(home country) - wellbeing (target country)]. Europe opts for the former, the Gulf or Singapore for the latter. Neither can tell us if a deviation from the status quo towards more migration would be beneficial or not since the systems are so different.

This is a good review. As much as I loved Caplan’s book, it’s good to point out its less compelling points.

I just feel like commenting one line in the opening part of the post.

Yes, that is somewhat true. But I have looked into this claim for Italy (where I’ve spent most of my life), and it turns out it is only true before adjusting for age. Foreign-born commit more crimes because they’re younger on average. When you compare homogeneous age groups (say 18-to-25-year-olds to 18-to-25-year-olds of the other group), it looks like the crime rate is virtually the same. I wouldn’t be surprised to find out this to be true of several other European countries. Also, crime rates are particularly high for illegal immigrants, but I wouldn’t know how much people self-select themselves into legal and illegal immigrants, so where the causality is. But the above descriptive statistic (same crime rate when accounting for age) could be a useful argument—in Europe—in favour of the case Caplan is arguing for in the US.

You are right, the same is true in Germany as well. There is even some evidence for lower crime rates for certain immigrant groups (e.g., first generation immigrants from Turkey, or SE-Asian/Chinese immigrants, if I recall correctly). Still, more crimes means more crimes, even if this is due to demographics, and the voters will punish the pro-immigrant parties accordingly.

The “lower crime rates for certain immigrant groups” is exactly why these figures are deceptive. If certain groups have lower crime rates, don’t lump together high crime and low crime subgroups as “immigrants” and claim that immigrants as a whole are neutral on crime rate.

Was there really that much immigration in 18th century Edinburgh? And in terms of agglomeration, I’m sure it was denser than, say, the highlands of Scotland, was it really that much compared to other cities in Britain?